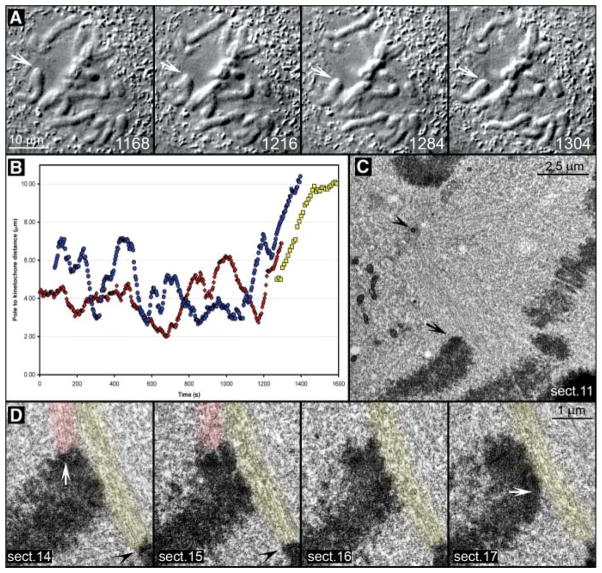

Fig. 1.

Leading kinetochores are not properly attached to microtubules during a chromosome’s attempt to congress. (A) Selected frames from a DIC time-lapse recording (also see Movie S2). The cell was fixed as one chromosome (arrows) moved toward the spindle equator (1304 s). (B) Distance versus time plot confirmed that the chromosome’s movement (red curve) was typical for chromosome congression [compare with blue and yellow curves, which represent movements of chromosomes shown in fig. S1 and Fig. 2, respectively]. (C) Lower-magnification EM image of the cell showing the position of the chromosome of interest (arrow) with respect to the spindle pole (arrowhead). (D) Selected 100-nm EM section from a full series through the centromere region of the chromosome. Note the prominent bundle of microtubules (highlighted red) connecting the trailing kinetochore (white arrow in section 14) to the proximal spindle pole. These microtubules approached the kinetochore at ~90° angle and terminated within the trilaminar kinetochore plate. By contrast, the leading kinetochore (white arrow, section 17) lacked attached microtubules but was laterally associated with a mature kinetochore fiber (highlighted yellow) that was attached to the kinetochore of a bioriented chromosome (black arrowheads in sections 14 and 15) positioned on the metaphase plate.