Abstract

Objective

To examine the prognostic value of perioperative N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in hip fracture patients.

Design

Blinded prospective cohort study.

Setting

Single centre trial at Turku University Hospital in Finland.

Participants

Inclusion criterion was admittance to the study hospital due to hip fracture during the trial period of October 2009—May 2010. Exclusion criteria were the patient's refusal and inadequate laboratory tests. The final study population consisted of 182 patients.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

NT-proBNP was assessed once during the perioperative period and later if clinically indicated, and troponin T (TnT) and ECG recordings were evaluated repeatedly. The short-term (30-day) and long-term (1000 days) mortalities were studied.

Results

Median (IQR) follow-up time was 3.1 (0.3) years. The median (IQR) NT-proBNP level was 1260 (2298) ng/L in preoperative and 1600 (3971) ng/L in postoperative samples (p=0.001). TnT was elevated in 66 (36%) patients, and was significantly more common in patients with higher NT-proBNP. Patients with high (>2370 ng/L) and intermediate (806–2370 ng/L) NT-proBNP level had significantly higher short-term mortality compared with patients having a low (<806 ng/L) NT-proBNP level (15 vs 11 vs 2%, p=0.04), and the long-term mortality remained higher in these patients (69% vs 49% vs 27%, p<0.001). Intermediate or high NT-proBNP level (HR 7.8, 95% CI 1.03 to 59.14, p<0.05) was the only independent predictor of short-term mortality, while intermediate or high NT-proBNP level (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.96, p=0.004), the presence of dementia (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.66, p=0.01) and higher preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) classification (HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.38, p=0.02) were independent predictors of long-term mortality.

Conclusion

An elevated perioperative NT-proBNP level is common in hip fracture patients, and it is an independent predictor of short-term and long-term mortality superior to the commonly used clinical risk scores.

Trial registration number

NCT01015105; Results.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no prior data on the combined effect of troponin T and N-terminal fragment of pro-brain natriuretic peptide on top of clinical preoperative risk evaluation in hip fracture patients.

All consecutive patients admitted to hospital due to an acute hip fracture during the trial period were initially included in the study, and the only exclusion criteria were the patient's refusal and inadequate laboratory testing.

Complete follow-up data were available for all the study patients.

The blinded setting of the trial prevents acquiring information on the effect of possible pharmacological treatment on the outcome.

Introduction

History of cardiovascular diseases and heart failure is common among hip fracture patients.1 2 However, clinical preoperative cardiac risk assessment of hip fracture patients is often complicated and inaccurate, and can lead to delays in surgery.3 This has led to a search for alternative ways to identify patients at high risk for complications. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a vasoactive hormone secreted mainly by the ventricular myocytes in response to cardiac wall tension,4 5 and the level of the N-terminal fragment of its prohormone (NT-proBNP) correlates with the extent of ventricular dysfunction.6 Increased preoperative BNP and NT-proBNP levels have been shown to predict cardiovascular complications in non-cardiac surgery.7–12 An earlier small study on orthopaedic patients has found preoperative BNP elevation to be superior to American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) physical status classification in independently predicting postoperative cardiac complications.13 Increased preoperative NT-proBNP has also been shown to independently predict short-term cardiovascular complications and cardiac death in non-cardiac surgery,9 14 and, in older patients, high perioperative NT-proBNP has also predicted long-term mortality.7 However, to our knowledge, only one small study has assessed the role of NT-proBNP in the prediction of perioperative and early postoperative cardiac complications in high-risk hip fracture patients.8 We recently showed that troponin T (TnT) is a strong independent predictor of short-term and long-term mortality in hip fracture patients,15 but there are no data on the combined effect of TnT and NT-proBNP on top of clinical preoperative risk evaluation in hip fracture patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether NT-ProBNP together with TnT provides useful additive prognostic information on the short-term and long-term outcome of unselected hip fracture patients.

Methods

This study (http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT01015105) is part of a wider protocol in progress to assess thrombotic and bleeding complications of invasive procedures in Western Finland.16–18 All consecutive hip fracture patients referred to Turku University hospital during a period of 7 months (from 19 October 2009 to 19 May 2010) were asked for consent to be included in this study. One patient declined. This resulted in 200 consecutive hip fracture patients. NT-proBNP measurements were missing in 18 patients and these patients were excluded; the final study population consisted of 182 hip fracture patients. An anaesthesiologist clinically evaluated the patients preoperatively, and assigned each patient an ASA physical status class. A lumbar epidural catheter was placed for pain control, and the patients received a mixture of a local anaesthetic and an opiate, from admission to the second postoperative morning. A chest X-ray study and basic blood chemistry tests were performed on admission and later according to clinical need. The patients were operated under spinal anaesthesia with isobaric bupivacaine. Significant postoperative blood loss was substituted with red blood cell transfusions. Hypotension (blood pressure <100/60) was treated with rapid fluid challenge, vasopressors and atropine, as appropriate. Patients’ cardiac medications (excluding diuretics) were continued throughout the hospital period. Blinded NT-proBNP measurements were performed once during the hospitalisation. Blinded TnT measurements and ECG recordings were performed on admission, before operation and on first and second postoperative days. Physicians were unaware of these results but additional tests were performed when clinically indicated.

NT-ProBNP and TnT levels were determined by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Modular E170 automatic analyser (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), which detects a NT-proBNP level of ≥50 ng/L. The patients were divided into tertiles according to the measured NT-proBNP level. When multiple NT-proBNP measurements were available, the highest of them was considered. The recommended diagnostic threshold of 0.03 µg/L was used to evaluate TnT elevation. Data on medical history, medication and cardiac risks were collected from the electronic medical records. These data were also used to evaluate the Revised Cardiac Risk Index value (RCRI, the Lee's score) for each patient.19 The patients were followed until April 2013. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland reviewed and approved the study protocol, all study patients gave their informed consent and the principles of the Helsinki declaration were followed.

Normality was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Skewed variables were presented as median and IQR, and categorical variables, as percentage. Analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U-test and χ2 test were used for comparison of variables, as appropriate. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier's method and Cox proportional hazards method. A Cox regression analysis with backward selection was performed to analyse the independent predictors of short-term and long-term mortality. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All computations were carried out with SPSS software (V. 22, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. Median (IQR) age of the patients was 84 (11) years. A history of heart failure was known in 26 (14%) patients and coronary artery disease in 56 (31%). Surgery was performed on the day of admission in 34 (19%) patients, 1 day after admission in 109 (60%), 2 days after admission in 24 (13%) and 3–5 days after admission in 12 (7%) patients. One patient died before the operation.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study population

| NT-proBNP level |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Low | Intermediate | High | ||

| Variable | n=182 | n=60 | n=61 | n=61 | p Value |

| NT-proBNP level | 1415 [2932] | 441 [342] | 1390 [860] | 5170 [6045] | |

| Men | 59 (32) | 20 (33) | 18 (30) | 21 (34) | 0.83 |

| Age (years) | 81.2±11.0 | 74.7±12.8 | 83.0±9.2 | 85.8±7.4 | <0.001 |

| History of any cardiovascular disease | 130 (71) | 36 (60) | 43 (70) | 51 (83) | 0.02 |

| History of heart failure | 26 (14) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | 18 (30) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 56 (31) | 12 (20) | 19 (31) | 25 (41) | 0.04 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 19 (10) | 3 (5) | 6 (10) | 10 (16) | 0.12 |

| Prior coronary revascularisation | 14 (8) | 2 (3) | 4 (7) | 8 (13) | 0.12 |

| Hypertension | 91 (50) | 22 (37) | 31 (51) | 38 (62) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (18) | 10 (17) | 9 (15) | 13 (21) | 0.62 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 39 (21) | 3 (5) | 10 (16) | 26 (43) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 10 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 9 (15) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 73 (40) | 16 (27) | 32 (53) | 25 (41) | 0.02 |

| Prior TIA or stroke | 30 (17) | 11 (18) | 11 (18) | 8 (13) | 0.68 |

| Preoperative ASA class | 3.28±0.57 | 3.10±0.63 | 3.27±0.52 | 3.48±0.50 | 0.001 |

| RCRI | 0.72±0.91 | 0.53±0.83 | 0.64±0.86 | 0.98±0.99 | 0.017 |

| Preoperative haemoglobin | 113±17 | 116±14 | 111±16 | 113±19 | 0.32 |

| Received red blood cell units | 1.51±1.53 | 1.68±1.70 | 1.66±1.54 | 1.18±1.30 | 0.125 |

| Perioperative TnT elevation | 66 (36) | 7 (12) | 18 (30) | 41 (67) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular medication at hospital admission | |||||

| Aspirin | 68 (37) | 20 (33) | 22 (36) | 26 (43) | 0.55 |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0.14 |

| Warfarin | 28 (15) | 3 (5) | 11 (18) | 14 (23) | 0.018 |

| β-blocker | 70 (38) | 14 (23) | 25 (41) | 31 (51) | 0.007 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 48 (26) | 9 (15) | 20 (33) | 19 (31) | 0.05 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 29 (16) | 7 (12) | 10 (16) | 12 (20) | 0.48 |

| Diuretic | 61 (34) | 13 (22) | 17 (28) | 31 (51) | 0.002 |

| Digoxin | 14 (8) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 7 (11) | 0.38 |

| Statin | 46 (25) | 14 (23) | 17 (28) | 15 (25) | 0.84 |

Data are presented as median (IQR), count (%) or mean±SD.

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status classification; NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index, Lee's score; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

NT-ProBNP was measured during hospitalisation, in all 182 patients, preoperatively in 117 (64%) and postoperatively in 86 (47%) patients; in 96 patients preoperative only, in 21 both preoperatively and postoperatively and in 65 patients postoperatively only. NT-ProBNP levels ranged from 50 to 72 100 ng/L, with a median (IQR) of 1415 (2932) ng/L. The median (IQR) NT-proBNP level was 1260 (2298) ng/L in preoperative samples and 1600 (3971) ng/L in postoperative samples (p=0.001). Those 21 patients who had preoperative and postoperative NT-proBNP measurements had a median preoperative proBNP level of 2220 (2964) ng/L and postoperative proBNP level of 3370 (5520) ng/L (p=0.001). Comparison of the NT-ProBNP tertiles is presented in table 1. There was no significant gender difference in NT-proBNP levels. Increasing age, history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure and dementia, were significantly associated with higher NT-proBNP levels. However, high NT-proBNP levels were detected even in patients with no prior cardiac morbidity, and 10 (16%) patients in the highest NT-proBNP tertile had no history of cardiovascular diseases. Multivariate logistic regression showed that age, renal failure and atrial fibrillation, were the independent predictors of higher NT-proBNP. Chest X-ray showed signs of congestive heart failure already on admission to hospital in 1 (2%) patient with low NT-proBNP (<806 ng/L), in 2 (3%) patients with intermediate NT-proBNP (806–2370 ng/L) and in 5 (8%) patients with high NT-proBNP (>2370 ng/L). Median (IQR) duration of hospitalisation was 6.0 (4.0) days and there was no difference in the duration between patients with low versus intermediate versus high NT-proBNP.

TnT was elevated in 7 (12%) patients with low NT-proBNP, in 18 (30%) patients with intermediate NT-proBNP and in 41 (67%) patients with high NT-proBNP (p<0.001).

Cardiac symptoms were infrequent in all NT-proBNP groups during hospitalisation. Shortness of breath was experienced by 10 (17%) patients with low, 10 (16%) patients with intermediate, and 19 (31%) patients with high NT-proBNP (p=0.08) and chest pain by 2 (3%) vs 2 (3%) vs 3 (5%), respectively, (p=0.87). Disorientation was observed in 23 (38%) vs 36 (59%) vs 46 (75%) of the patients in low, intermediate and high NT-proBNP groups, respectively, (p<0.001).

At 30 days follow-up, 17 (9%) patients had died (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the patients who died within 30 days of hospital admission and patients who survived

| Died within 30 days | Alive after 30 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n=17 | n=165 | p Value |

| NT-ProBNP level | 2700 [10 435] | 1230 [2736] | 0.01 |

| Men | 9 (53) | 50 (30) | 0.058 |

| Age (years) | 84.7±6.3 | 80.8±11.4 | 0.17 |

| History of any cardiovascular disease | 15 (88) | 115 (70) | 0.11 |

| History of heart failure | 2 (12) | 24 (15) | 0.76 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (29) | 51 (31) | 0.90 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 3 (18) | 15 (9) | 0.31 |

| Prior coronary revascularisation | 2 (12) | 12 (7) | 0.51 |

| Hypertension | 10 (59) | 81 (49) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (35) | 26 (16) | 0.04 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (35) | 33 (20) | 0.14 |

| Renal failure | 2 (12) | 8 (5) | 0.23 |

| Dementia | 9 (53) | 64 (39) | 0.26 |

| Prior TIA or stroke | 2 (12) | 28 (17) | 0.58 |

| Preoperative ASA score | 3.4±0.5 | 3.3±0.6 | 0.25 |

| RCRI | 0.8±1.0 | 0.7±0.9 | 0.83 |

| Perioperative troponin T elevation | 11 (65) | 55 (33) | 0.01 |

Data are presented as median (IQR), count (%) or mean±SD.

ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status classification; NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index, Lee's score; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

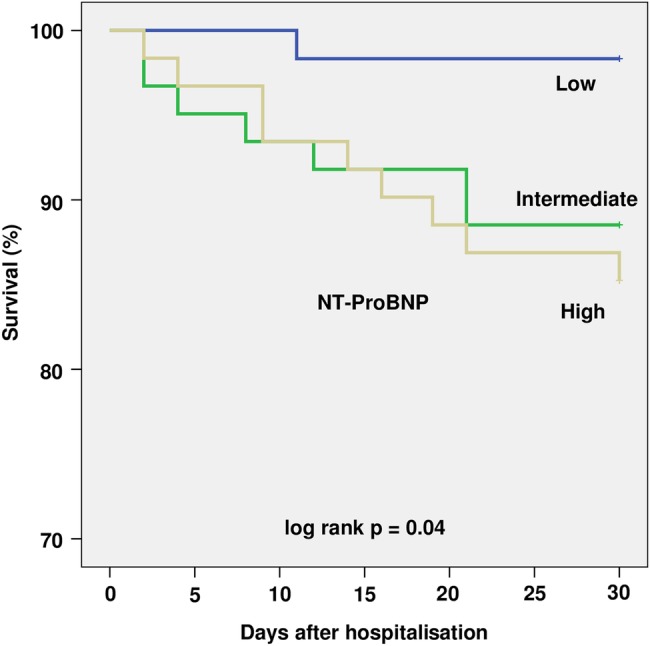

Patients with high and intermediate NT-proBNP had significantly higher 30-day mortality compared with patients having low NT-proBNP (15% vs 11% vs 2%, p=0.04), as shown in figure 1. The patients who died during the first 30 days had a median (IQR) proBNP level of 2700 (10 435) ng/L compared to 1230 (2736) ng/L in patients who survived the first 30 days (p=0.002). Of the patients with no TnT elevation, 5% died during the first 30 days: no patients with low proBNP versus 6 (10%) of the patients with intermediate or high NT-proBNP (p=0.02). Of the 66 patients with a perioperative TnT elevation, 11 (17%) died during the first 30 days, with no difference in mortalities regarding the NT-proBNP levels in these patients. Intermediate/high versus low NT-proBNP levels (HR 7.8, 95% CI 1.03 to 59.14, p<0.05) remained the only independent predictor of short-term mortality in a Cox regression model including age, renal impairment, TnT elevation, NT-proBNP levels, ASA and Lee scores.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival at 30 days follow-up in patients with low, intermediate and high NT-proBNP level during index hospitalisation. NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Complete follow-up data up to 1000 days was available for all 182 patients. Median (IQR) follow-up time was 3.12 (0.28) years. The overall mortality at 1000 days was 48% (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of patients who died within 1000 days of hospital admission and patients who survived

| Died within 1000 days | Alive after 1000 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n=88 | n=94 | p Value |

| NT-ProBNP level | 2295 [4403] | 913 [1679] | <0.001 |

| Men | 32 (36) | 27 (29) | 0.27 |

| Age (years) | 84.1±9.7 | 78.5±11.6 | <0.001 |

| History of any cardiovascular disease | 71 (81) | 59 (63) | 0.008 |

| History of heart failure | 18 (20) | 8 (9) | 0.02 |

| Coronary artery disease | 34 (39) | 22 (23) | 0.03 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 11 (13) | 8 (9) | 0.38 |

| Prior coronary revascularisation | 9 (10) | 5 (5) | 0.21 |

| Hypertension | 48 (55) | 43 (46) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (20) | 14 (15) | 0.33 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27 (31) | 12 (13) | 0.003 |

| Renal failure | 7 (8) | 3 (3) | 0.16 |

| Dementia | 45 (51) | 28 (30) | 0.003 |

| Prior TIA or stroke | 17 (19) | 13 (14) | 0.32 |

| Preoperative ASA score | 3.4±0.5 | 3.2±0.6 | 0.003 |

| RCRI | 0.9±1.0 | 0.6±0.9 | 0.02 |

| Troponin T elevation | 40 (45) | 26 (28) | 0.01 |

Data are presented as median [IQR], count (%) or mean±SD.

ASA class, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status classification; NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index, Lee's score; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

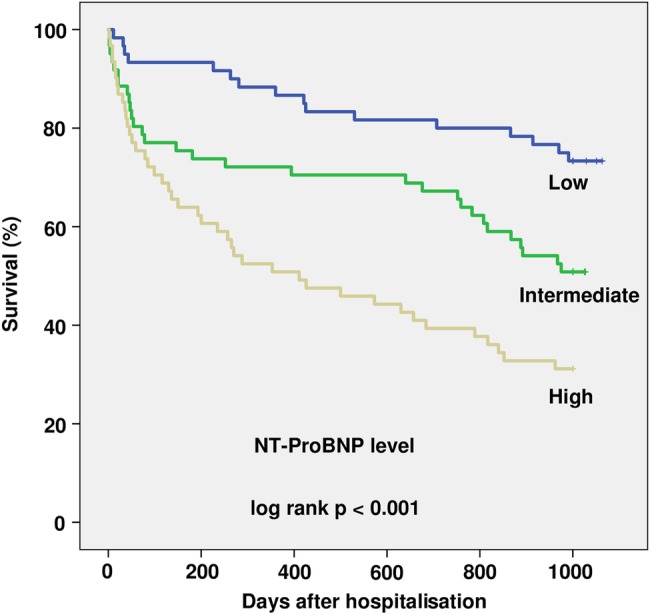

The mortality remained constantly higher in patients with high and intermediate NT-proBNP compared to patients with low NT-proBNP (69% vs 49% vs 27%, p<0.001), as shown in figure 2. Intermediate/high NT-proBNP levels (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.96, p=0.004), the presence of dementia (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.66, p=0.01) and higher preoperative ASA class (HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.38, p=0.02) remained independent predictors of long-term mortality in a Cox regression model including NT-proBNP levels, TnT elevation, age, renal impairment, the presence of dementia, atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease, preoperative ASA and Lee's scores. In patients with no perioperative TnT elevation, intermediate/high NT-proBNP (HR 3.17; 95% CI 1.64 to 6.10, p=0.001) was the only independent predictor of 1000-day mortality, while in patients with a perioperative TnT elevation, NT-proBNP did not carry a significant predictive value.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival at 1000 days follow-up in patients with low, intermediate and high NT-proBNP level during the index hospitalisation. NT-proBNP, N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

The present study showed that high NT-proBNP levels are common in hip fracture patients, and that there is a significant graded association between increasing NT-proBNP level and short-term and long-term mortality. Furthermore, measurement of this natriuretic peptide provided useful independent prognostic information on top of currently used risk scores and troponin levels. While perioperative NT-proBNP level was the only independent predictor of short-term mortality, perioperative NT-proBNP level, preoperative ASA class and the presence of dementia, were independent predictors of long-term mortality. Of note, the clinical characteristics of the patients and currently used risk scores not provide useful information on the short-term mortality in these fragile acute patients.

When patients with a perioperative TnT elevation were analysed separately, the short-term mortality was not affected by the perioperative NT-proBNP level, but the long-term mortality was higher if the patient also had a high NT-proBNP level. However, a high NT-proBNP level did not remain a significant predictor of long-term mortality in this relatively small patient group with a poor overall prognosis.

In elective non-cardiac surgery, a low NT-proBNP level of 201 ng/L has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity to predict perioperative cardiovascular complications,9 while in emergency orthopaedic surgery patients, a preoperative NT-proBNP level of ≥741–842 ng/L was the best cut-off level in evaluating the risk of in-hospital and long-term cardiac complications.7 20 In line with these observations, the best cut-off level for the prediction of short-term mortality was low also in this old patient group with frequent comorbidities, and most of the difference in short-term mortality was already observed between the low and intermediate NT-proBNP groups. The increase in long-term mortality between the NT-proBNP groups was, however, more stable and, not unexpectedly, dementia and poor ASA group were the other independent predictors of long-term mortality.

Unexpectedly, some patients with no history of cardiovascular diseases or renal failure had a high NT-proBNP level, supporting the view that major trauma and surgery, or heavy use of intravenous fluids in the perioperative period, may cause stress on the heart and lead to elevated NT-proBNP levels. High coincidence of TnT elevation also suggests that a perioperative myocardial injury is a major cause of elevated NT-proBNP levels in this patient group.

To our knowledge, there has only been one earlier study assessing NT-proBNP levels in hip fracture patients. In this study, of only 69 frail hip fracture patients with a high-ASA class, a preoperative NT-proBNP level exceeding 3984 ng/L was an independent predictor of perioperative cardiac complications, but no association was found between increased NT-proBNP and mortality at 3 months follow-up.8 Contrary to these findings, our study showed that high NT-proBNP is an independent predictor of both short-term and long-term mortalities, and that there is a five-fold increase in short-term mortality already at NT-proBNP level exceeding 805 ng/L.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. First, the study population of 182 patients, although bigger than in similar earlier studies, is relatively small. Second, the idea was to obtain NT-proBNP samples preoperatively in all patients, but due to weekends and public holidays, preoperative tests were obtained in 64% of the patients only. Since this was a blind evaluation, it is not possible to assess how pharmacological treatments may have affected the outcome. The strengths of this study are the prospective nature of the registry, inclusion of all consecutive hip fracture patients and complete follow-up data of all 182 patients.

In conclusion, an elevated perioperative NT-proBNP level is common in surgically treated hip fracture patients, and an independent predictor of short-term and long-term mortality that is superior to the commonly used clinical risk scores, and an efficient tool in detecting those patients who are at greater risk of death. Measurement of NT-proBNP and TnT in hip fracture patients could lead to the detection of patients at high risk of either early or later death after the operation. The prognosis of high risk patients might be improved with appropriate cardiac care, especially in those patients with no previous cardiovascular history and no medications.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors participated in designing this study. MS recruited the patients. NS operated on the patients. PN collected the data. PN and TK analysed the data, and PN, TK, MS and JA interpreted the data. PN wrote the first draft, and the other authors reviewed it and provided further contributions and suggestions. All the authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Helsinki, Finland.

Competing interests: All the authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pd and declare: the authors had financial support from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, for the submitted work.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hietala P, Strandberg M, Strandberg N et al. . Perioperative myocardial infarctions are common and often unrecognized in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1087–91. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182827322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen MW, Gullerud RE, Larson DR et al. . Impact of heart failure on hip fracture outcomes: a population-based study. J Hosp Med 2011;6:507–12. 10.1002/jhm.918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeets SJ, Poeze M, Verbruggen JP. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of geriatric patients with hip fracture. Injury 2012;43:2146–51. 10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa Y, Nakao K, Mukoyama M et al. . Natriuretic peptides as cardiac hormones in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. The ventricle is a major site of synthesis and secretion of brain natriuretic peptide. Circ Res 1991;69:491–500. 10.1161/01.RES.69.2.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasue H, Yoshimura M, Sumida H et al. . Localization and mechanism of secretion of B-type natriuretic peptide in comparison with those of A-type natriuretic peptide in normal subjects and patients with heart failure. Circulation 1994;90:195–203. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt PJ, Richards AM, Nicholls MG et al. . Immunoreactive amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-PROBNP): a new marker of cardiac impairment. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997;47:287–96. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2361058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong CP, Ryan JE, van Gaal WJ et al. . Usefulness of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide to predict postoperative cardiac complications and long-term mortality after emergency lower limb orthopedic surgery. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:865–72. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oscarsson A, Fredrikson M, Sörliden M et al. . N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is a predictor of cardiac events in high-risk patients undergoing acute hip fracture surgery. Br J Anaesth 2009;103:206–12. 10.1093/bja/aep139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun KH, Jeong MH, Oh SK et al. . Preoperative plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide concentration and perioperative cardiovascular risk in elderly patients. Circ J 2008;72:195–9. 10.1253/circj.72.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oscarsson A, Fredrikson M, Sörliden M et al. . Predictors of cardiac events in high-risk patients undergoing emergency surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:986–94. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutt RC, Cevik C, Phy MP. Plasma N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide as a marker for postoperative cardiac events in high-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:137–40. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dernellis J, Panaretou M. Assessment of cardiac risk before non-cardiac surgery: brain natriuretic peptide in 1590 patients. Heart 2006;92:1645–50. 10.1136/hrt.2005.085530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villacorta Junior H, Castro IS, Godinho M et al. . B-type natriuretic peptide is predictive of postoperative events in orthopedic surgery. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010;95:743–8. 10.1590/S0066-782X2010005000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh HM, Lau HP, Lin JM et al. . Preoperative plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide as a marker of cardiac risk in patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Br J Surg 2005;92:1041–5. 10.1002/bjs.4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hietala P, Strandberg M, Kiviniemi T et al. . Usefulness of troponin T to predict short-term and long-term mortality in patients after hip fracture. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:193–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Airaksinen KE, Korkeila P, Lund J et al. . Safety of pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation during uninterrupted warfarin treatment—the FinPAC study. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:3679–82. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Airaksinen KE, Grönberg T, Nuotio I et al. . Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1187–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiviniemi T, Puurunen M, Schlitt A et al. . Performance of bleeding risk-prediction scores in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1995–2001. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM et al. . Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999;100:1043–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.100.10.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong CP, Lim WK, Velkoska E et al. . N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 levels and their association with postoperative cardiac complications after emergency orthopedic surgery. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1365–73. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]