Abstract

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) have gradually become important and regular components of the policy-making process in Mexico since, and even before, the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) called for interventions and policies aimed at tackling the social determinants of health (SDH). This paper presents two case studies to show how public policies addressing the SDH have been monitored and evaluated in Mexico using reliable, valid, and complete information, which is not regularly available. Prospera, for example, evaluated programs seeking to improve the living conditions of families in extreme poverty in terms of direct effects on health, nutrition, education and income. Monitoring of Prospera's implementation has also helped policy-makers identify windows of opportunity to improve the design and operation of the program. Seguro Popular has monitored the reduction of health inequalities and inequities evaluated the positive effects of providing financial protection to its target population. Useful and sound evidence of the impact of programs such as Progresa and Seguro Popular plus legal mandates, and a regulatory evaluation agency, the National Council for Social Development Policy Evaluation, have been fundamental to institutionalizing M&E in Mexico. The Mexican experience may provide useful lessons for other countries facing the challenge of institutionalizing the M&E of public policy processes to assess the effects of SDH as recommended by the WHO CSDH.

Keywords: monitoring, evaluation, health inequities, health inequalities, public policies, social determinants of health, Mexico

Introduction

A decade ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) called for interventions and policies aimed at the social determinants of health (SDH). One of its key recommendations was to measure health inequality and inequity while evaluating the impact of actions addressing SDH (1). Several public policies tackling health inequities, that result in part by unfair societal factors, have been implemented in Mexico – since and even before the CSDH was established. Most of these public policies aimed to fight poverty and/or protect the income of nearly half of Mexico's population. However only a few of them, have been rigorously monitored and evaluated. We focus herein only on public policies that have explicitly addressed “health-influencing experiences that result from the unequal distribution of political power, income, and resources, the resulting disparity in daily living circumstances, such as access to healthcare and education and living and working conditions, and the lower potential of socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals to lead prosperous lives” (1).

The absence of rigorous monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is explained in part by the fact that reliable, valid, and complete data are not regularly available. Case studies are used here to show how national policies in Mexico have been monitored and evaluated using available empirical evidence. Together with the creation of government agencies and instruments, and some fostering by WHO CSDH, Mexico has begun to institutionalise M&E.

M&E of policies tackling SDH in Mexico

For this study we selected two national public policies that tackled health inequities associated with the SDH and implemented M&E. The first is the conditional cash transfer program, now called Prospera.1 The program was implemented in 1997 to ameliorate the extreme poverty in which a quarter of Mexico's population had been living for the previous two decades. Prospera has systematically demonstrated direct effects on health (2–7) and nutrition (8–11) outcomes, and on important social determinants such as education (12–14). The program is regarded as setting international standards for social policy evaluation (15, 16).

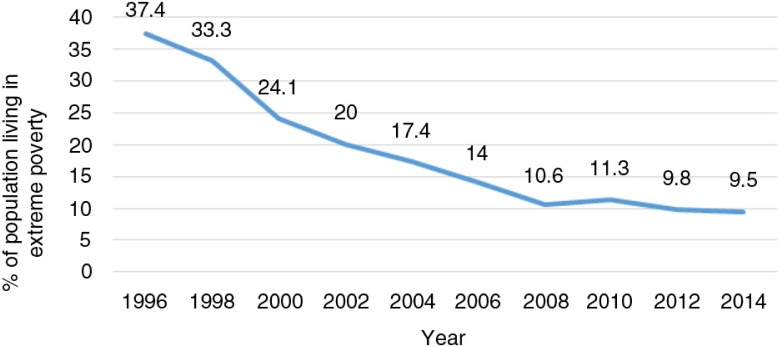

The monitoring of Prospera's implementation has also helped policy-makers identify windows of opportunity to improve its design and operation (17). One of the main indicators used to monitor its performance is the percentage of people living in extreme poverty. This has been regularly measured every 2 years through the national income and expenditure surveys were introduced. Since Prospera was introduced, as this percentage has been gradually diminishing (Fig. 1). Although this reduction cannot be attributed only to the Prospera program, there is evidence indicating its effect on alleviating, or at least containing, the growth of extreme poverty (15, 19–24).

Fig. 1.

Extreme poverty evolution in Mexico, 1996–2014. From Ref. (18).

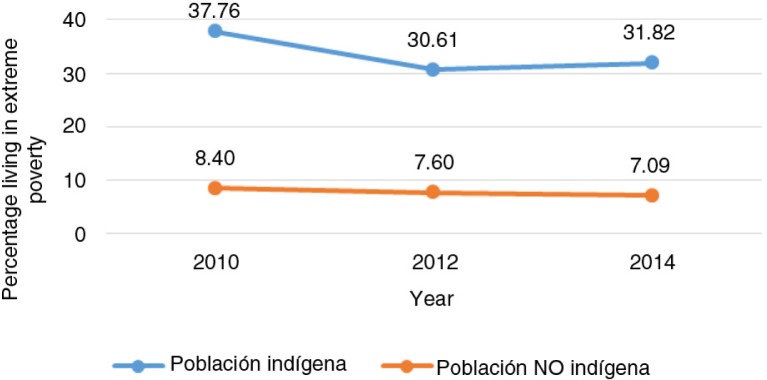

This indicator – the percentage of the population living in extreme poverty – does not, however, identify who the most socially disadvantaged individuals living in extreme poverty are. Figure 2 shows that most people living in extreme poverty are indigenous.2 This highlights the importance of developing specific strategies to address this important inequity.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of population living in extreme poverty by indigenous condition, 2010–2014. From Ref. (25).

The more recent program, called Seguro Popular de Salud (SPS), is a national insurance scheme designed in 2002 and implemented since that time to protect the income of the population not covered by social security. It provides explicit health insurance coverage for a fairly comprehensive benefit package. Evaluations of SPS have provided empirical evidence of the positive effects of this financial protection, especially for the low-income population (26–32). Evidence shows a reduction in the inequitable allocation of resources between the insured and the uninsured population (33, 34).

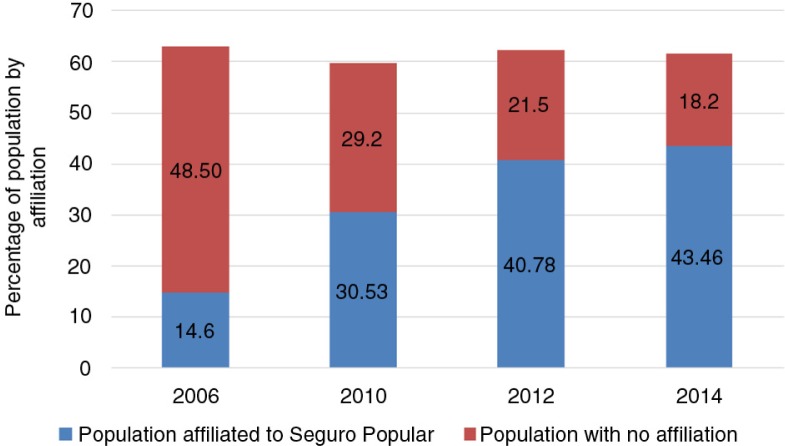

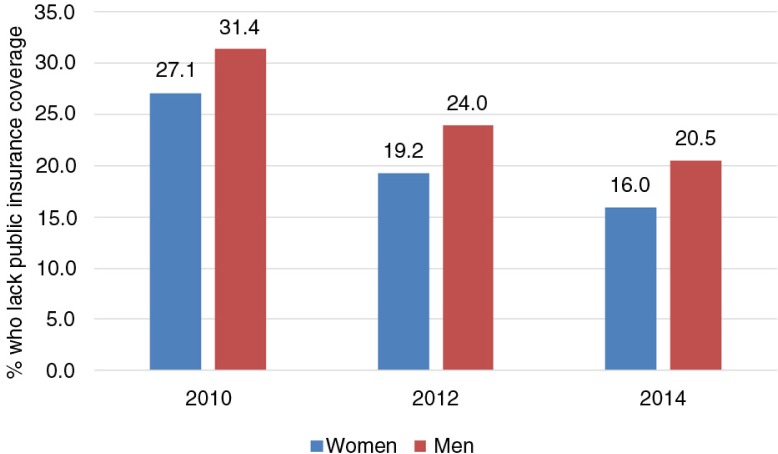

Seguro Popular has been monitored using health insurance coverage as the main indicator. National health surveys and national income and expenditure surveys were used to gather data. Both datasets have shown increasing coverage of the affiliated population (Fig. 3). When disaggregated by sex, the population not covered by a public insurance scheme shows how men have a lower coverage than women (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of population by insurance coverage, 2006–2014. From Refs. (18, 37).

Fig. 4.

Percentage who lack insurance coverage by sex, 2010–2014. From Ref. (18).

Despite this progress, full access to public health care in Mexico has not yet been achieved. Users keep seeking private services to take care of their health problems resulting in still relatively high out-of-pocket payments. Out-of-pocket payments have diminished from 51.7% of total health expenditures in 2004 to only 44% in 2013 (32).

Institutionalization of M&E

M&E has gradually become an important component of public policy-making in Mexico, and Prospera has set the example. Soon after the implementation of Prospera, Congress mandated that all programs with operating rules3 had to be evaluated annually by external evaluators. The mandate covered approximately 25–30% of the federal budget for programs. The number of evaluations jumped from single digits to over a hundred in 2001 and in subsequent years (35). Seguro Popular was one of those programs.

The Social Development Law and the creation of the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Policy (CONEVAL) in 2004 further institutionalized evaluation. CONEVAL was designed as an autonomous institution whose mission was to measure poverty reduction results nationally and coordinate evaluation of social programs by the federal government. Its independence and technical capacities4 as well as the mandate allowed it to advance construction of the social sector M&E system. The experience of CONEVAL has become a benchmark for other developing countries undertaking M&E reforms (35).

Although there is more evaluation to be done, still very little of that information has been effectively used. There was little awareness then of the role that evaluation plays in improving government programs. Although by law, every health-related policy should undergo some form of evaluation, evaluation guidelines have not always been followed. They are difficult to enforce. Evaluation activity has also lacked the incentives and institutional arrangements to ensure use of the findings.

More recently, under National Health Programs since 2007, the health sector agenda has explicitly addressed persistent inequalities associated with the distribution of wealth and other socioeconomic factors, plus health system characteristics that shape the rules of financing and access to health services (36). Furthermore, in order to monitor progress toward the overall goal of achieving more inclusive development, indicators that address SDH have been included in the current government's National Health Program (37) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Monitoring indicators of the National Health Program, 2013–2018

| Indicator | Baseline (2012) (%) | Value (2014) (%) | Goal (2018) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of the population without public health insurance | 21.5 | 18.2 | 6.0 |

| Percentage of the population covered by public insurance and using public health care services | 53.8 | 63.3 | 80.0 |

| Percentage of households of the lowest income quintile with catastrophic health care expenditures | 4.6 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

From Ref. (36).

Future challenges

Although institutional foundations are in place, important challenges to achieving full institutionalization of M&E remain in Mexico. The main challenge is the widespread use of M&E as a transparent policy-making practice. Transparency and accountability have fostered M&E of public policies in Mexico. However, the utility of these practices is yet to be fully recognized in policy-making circles. This challenge is closely linked to the following:

Develop capacity building for evaluation at all levels of government to measure the effect of public policies on target populations.

Foster the practice of monitoring in policy-making. Monitoring is still is not as developed as evaluation. Monitoring mostly relies on administrative data that are usually not as reliable and complete as the data used for longer-term in-depth evaluations that focus more on outcomes and impacts.

Strengthen health information systems to provide disaggregated data by socioeconomic groups for monitoring health inequalities. This is essential for everyday decision-making, because government performance is strongly linked to services and products that need to be managed on a daily basis. Public policy practices must complement each other with equally rigorous methodologies.

In sum, M&E has gradually become an important and regular part of the policy-making process in Mexico. Both the production of useful and sound evidence on the impact of programs such as Prospera and Seguro Popular, as well as legal mandates, and strong institutions such as CONEVAL, have been critical in institutionalizing M&E. The Mexican experience may provide useful lessons for other countries wanting to assess the effects of SDH by institutionalizing, monitoring, and evaluating their own public policy processes.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to aknowledge that this paper is a product of a WHO project on Monitoring Equity-oriented progress towards Universal Health Coverage, 2013–2015.

This paper is part of the Special Issue: Monitoring health determinants with an equity focus. More papers from this issue can be found at www.globalhealthaction.net

Footnotes

Prospera was originally named Progresa in 1997. It was then changed to Oportunidades in 2002 and to Prospera in 2014. These name changes have been principally because of different political parties being in power. The essential characteristics of a conditional cash transfer program have remained unchanged.

Indigenous are those individuals that either speak a native language or live in a household where a native language is spoken.

Rules of operation required every program that received federal budget to provide basic information about its design, objectives, performance indicators, target population, and procedures.

CONEVAL relies on an independent collegiate body made up of six academic councilors. These six individuals are democratically elected for a period of 4 years, and they are chosen from certified academic institutions. The councilors are involved in all of the agency's decisions and the definition and review of evaluation projects. They also provide general guidance on the administrative direction of the institution and play an important role in the methodologies for poverty measurement.

Author’s contribution

AMV conceptualized the article, conducted literature review and drafted the manuscript.

Conflict of interest and funding

The author worked for the Mexican Ministry of Health from 2001 to 2008 participating in the design and development of Seguro Popular. He also worked for the Oportunidades program from 2009 to 2011 participating in planning and evaluation of the program. The author has not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bautista S, Bertozzi S, Gertler P, Gutiérrez JP, Hernandez M. The impact of Oportunidades on health status, morbidity, and service utilization among beneficiary population: short-term results in urban areas and medium-term results in rural areas. Cuernavaca, Mexico: National Institute of Public Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber SL, Gertler PJ. The impact of Mexico's conditional cash transfer programme, Oportunidades, on birth weight. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1405–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: an analysis of Mexico's Oportunidades. Lancet. 2008;371:828–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández-Prado B, Ramírez D, Moreno H, Laird N. Impact of Oportunidades on the reproductive health of the target population. Cuernavaca: National Public Health Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todd JE, Winters P. The effect of early interventions in health and nutrition on on-time school enrollment: evidence from the Oportunidades Program in rural Mexico. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2011;59:549–81. doi: 10.1086/658347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bautista S, Bertozzi S, Leroy JL, López Ridaura R, Sosa Rubí SG, Téllez Rojo MM, et al. Ten years of Oportunidades in rural zones: impact on the use of services and the health status of beneficiaries. In: Bertozzi S, González de la Rocha M, editors. External evaluation of the Oportunidades program. Ten years of intervention in rural areas (1997–2007) Mexico City: Ministry of Social Development; 2008. pp. 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. 10-year effect of Oportunidades, Mexico's conditional cash transfer programme on child growth, cognition, language, and behavior: a longitudinal follow-up study. Lancet. 2009;374:1997–2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera JA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Habicht JP, Shamah T, Villalpando S. Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (PROGRESA) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: a randomized effectiveness study. JAMA. 2004;291:2563–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leroy JL, García A, García R, Domínguez C, Rivera J, Neufeld L. The Oportunidades program increases the linear growth of children enrolled at young ages in urban Mexico. J Nutr. 2008;138:793–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villalpando S, Shamah T, García A, Mundo V, Domínguez C, Mejía F. The prevalence of anemia decreased in Mexican preschool and school-age children from 1999 to 2006. Salud Publica Méx. 2009;51(Suppl. 4):S507–14. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342009001000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker SW. Evaluation of impact of Oportunidades on school enrolment, grade repetition and dropout rates. In: Hernández B, Hernández M, editors. Results of the external evaluation of the education, health, and nutrition programme. Cuernavaca: Centre for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology, National Public Health Institute; 2005. pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker SW. Impact evaluation of the Oportunidades Human Development Programme on elementary, secondary, and high school enrolment. Mexico City: Centre for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology, National Public Health Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker S, Behrman J. Monitoring of young adults from households in the Oportunidades programme since 1998: impact on education and performance testing. In: Bertozzi S, González de la Rocha M, editors. External evaluation of the Oportunidades program. Ten years of intervention in rural areas (1997–2007) Mexico City: Ministry of Social Development; 2008. pp. 43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy S. Progress against poverty: sustaining Mexico's PROGRESA-OPORTUNIDADES Program. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008137. CD008137. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mir Cervantes C, Coronilla Cruz R, Castro Flores L, Santillanes Chacón S, Loyola Mandolini D. External evaluation of Oportunidades 2008, 1997–2007: 10 years of intervention in rural areas volume IV. Oportunidades day to day: evaluation of Oportunidades’ operations and services for beneficiaries. Mexico City: Secretaría de Desarrollo Social; 2008. Operational evaluation of the quality of Oportunidades’ program services in rural areas; pp. 15–172. Available from: https://prospera.gob.mx/EVALUACION/en/wersd53465sdg1/docs/2008/2008_volume_iv.pdf [cited 30 June 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Council for Social Development Evaluation (CONEVAL) Mexico City: CONEVAL; 2014. Anexo estadístico. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arroyo Ortiz JP, Ordaz Díaz JL, Li JJ, Zaragoza López ML. External evaluation of Oportunidades 2008, 1997–2007: 10 years of intervention in rural areas. Mexico City: Secretaría de Desarrollo Social; 2008. Effects on beneficiary household consumption and investment. Available from: https://prospera.gob.mx/EVALUACION/es/wersd53465sdg1/docs/2008/2008_consumo_inversion.pdf [cited 30 June 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodríguez E, Pasillas M. Effects of Oportunidades on the local economy and infrastructure in rural áreas 10 years on. Mexico City: Ministry of Social Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez E, Freije S. An assessment of the impact of Oportunidades on employment, wages and intergenerational occupational mobility. In: Bertozzi S, González de la Rocha M, editors. External evaluation of the Oportunidades Program 2008: ten years of intervention in rural areas (1997–2007) Mexico City: Ministry of Social Development; 2008. pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee D, Todd P. The longer-term effects of human capital enrichment programs on poverty and inequality: Oportunidades in Mexico. Estud Econ. 2011;38:67–100. doi: 10.4067/s0718-52862011000100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Debowicz D, Golan J. The impact of Oportunidades on human capital and income distribution in Mexico: a top-down/bottom-up approach. J Policy Model. 2014;36:24–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Council for Social Policy Evaluation (CONEVAL) Evolución de la pobreza en México. México City: CONEVAL; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Social protection strategy for the indigenous population care, 2014–2018. Available from: https://prospera.gob.mx/EVALUACION/es/wersd53465sdg1/inicio/CNPDHO_Estrategia_Indigena_2014-2018.pdf [cited 30 June 2015]

- 26.Avila-Burgos L, Servan-Mori E, Wirtz V, Sosa-Rubi SG, Salinas-Rodriguez A. Efectos del Seguro Popular sobre el gasto en salud en hogares mexicanos a diez años de su implementación. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(Suppl. 2):S91–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knaul F, González Pier E, Gómez Dantés O, García Junco D, Arreola Ornelas H, Barraza Lloréns M, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sosa-Rubí S, Salinas-Rodríguez A, Galárraga O. Impact of Seguro Popular on catastrophic and out-of-pocket expenditures in rural and urban Mexico, 2005–2008. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(Suppl. 4):S425–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosa-Rubí SG, Salinas-Rodríguez A, Galárraga O. Impacto del Seguro Popular en el gasto catastrófico y de bolsillo en el México rural y urbano, 2005–2008. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53:425–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG, Salinas-Rodríguez A, Sesma-Vázquez S. Health insurance for the poor: impact on catastrophic and out-of-pocket health expenditures in Mexico. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11:437–47. doi: 10.1007/s10198-009-0180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernández-Torres J, Avila-Burgos L, Valencia-Mendoza A, Poblano-Verástegui O. Seguro Popular's initial evaluation of household catastrophic health spending in Mexico. Salud Pública Mex. 2008;10:18–32. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642008000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez Valle A, Terrazas P, Álvarez F. How to reduce health inequities by targeting social determinants: the role of the health sector in Mexico. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2014;35:264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López MJ, Valle AM, Aguilera N. Reforming the Mexican Health System to achieve effective health care coverage. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1:181–8. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2015.1058999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grogger J, Arnold T, León AS, Ome A. Heterogeneity in the effect of public health insurance on catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures: the case of Mexico. Health Policy Plan. 2014;30:593–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castro F, López-Acevedo G, Beker G, Fernández X. Mexico's monitoring and evaluation system: scaling up from the sectorial to the national level. Evaluation Capacity Development Working Paper Series 20. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gobierno de la República. México City: Gobierno de la República; 2013. Programa Sectorial de Salud, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutiérrez JP, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, Villalpando-Hernández S, Franco A, Cuevas-Nasu L, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición. Resultados Nacionales. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2012. [Google Scholar]