Abstract

Retinal degenerative diseases are a leading cause of irreversible blindness. Retinal cell death is the main cause of vision loss in genetic disorders such as retinitis pigmentosa, Stargardt disease, and Leber congenital amaurosis, as well as in complex age-related diseases such as age-related macular degeneration. For these blinding conditions, gene and cell therapy approaches offer therapeutic intervention at various disease stages. The present review outlines advances in therapies for retinal degenerative disease, focusing on the progress and challenges in the development and clinical translation of gene and cell therapies. A significant body of preclinical evidence and initial clinical results pave the way for further development of these cutting edge treatments for patients with retinal degenerative disorders.

Introduction

Blinding diseases of the retina

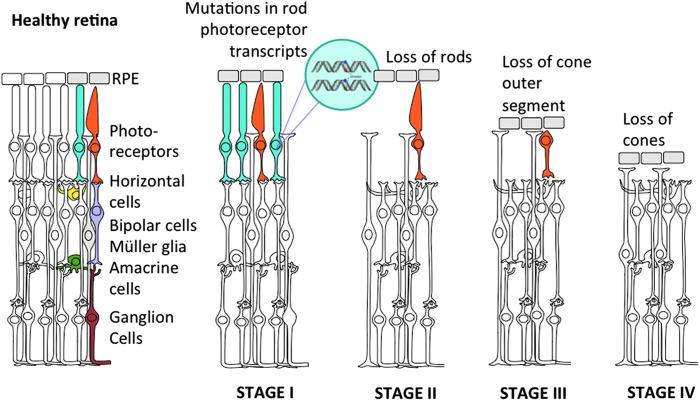

Retinal diseases are a major cause of irreversible blindness. These conditions can be caused genetically or acquired later in life. Complex diseases have both genetic and acquired counterparts. Most common forms of multifactorial retinal diseases include macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and retinoblastoma. Inherited retinal degenerations, on the other hand, are entirely linked to mutations in retinal neurons and their underlying epithelium. Retinal cell death is the main cause of vision loss in many blinding conditions, for which gene and cell therapy approaches offer intervention at various stages (see Fig. 1 for an example). Basic research on how and why retinal cells die in various diseases is crucial for the development of treatment strategies to prevent or reverse vision loss by gene and cell therapy. This review focuses on the latest developments in laboratory and clinical aspects of gene and cell therapy for retinal diseases.

Figure 1.

Progression of a genetic disease through retinal cell death: autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa serves as an example. Healthy retina is composed of five neuronal types, with the photoreceptors being the primary neurons. In retinitis pigmentosa, mutations mostly in rod transcripts (shown in blue) lead to degeneration of these cells (stage I) followed by progressive cone (orange) degeneration (stages II and III). In the final stage (stage IV), all photoreceptor cells are lost, leaving the retina blind. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Why the eye?

The eye represents an ideal target for gene and cell therapies: it is easily accessible and small (requiring a low volume of virus per active dose), highly compartmentalized (permitting various ocular tissues—anterior chamber, vitreous cavity, or subretinal space—to be specifically targeted), and separated from the rest of the body by the blood–retinal barrier (ensuring ocular immune privilege and minimal systemic dissemination). As the retinal cells normally do not divide, the cell population remains stable, making it possible to use nonintegrating vectors for sustained transgene expression (for review, see References 1–3). Other important reasons why the eye has been at the forefront of gene and cell therapies is the fact that the contralateral eye can serve as an internal control, which is extremely helpful in evaluation of outcomes. Last, progress in imaging technologies (such as optical coherence tomography, adaptive optics) for visualizing this accessible part of the body has been of great value in both diagnostics and follow-up after treatments.

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy is an emerging therapeutic approach to treat, cure, or prevent a disease by providing a gene with therapeutic action. Diseases associated with loss-of-function mutations can be treated by gene replacement therapy (also referred to as gene supplementation), whereas those associated with gain-of-function mutations require eradication of mutant alleles in addition to supplementing the gene. In all instances, the genetically modifying factors (DNA or RNA and/or their interacting proteins) need to be delivered into the relevant target cells. Advances in the design and production of gene delivery vectors have been an important part of gene therapy progress and are discussed below. In addition, advances in molecular genetics and rapidly evolving knowledge of retinal biology have allowed significant progress to be made in gene therapy for retinal disorders, with promising results not only in animal models, but also in humans.

Gene delivery: viruses, nanoparticles, physical methods

Most gene therapy studies use viral vectors, such as adenovirus (Ad), adeno-associated virus (AAV), or lentivirus (LV), to enable gene delivery to the retina. Two local administration routes allow viral vectors to access retinal cells. Viral vectors can either be injected into the vitreous cavity via an intravitreal injection, or they can be injected into the subretinal space, created through a transient retinal detachment. Intravitreal injections deliver the vector in proximity to the retinal ganglion cells and are the preferred delivery route for targeting the inner retina. Subretinal injections deliver vectors between the photoreceptors and their underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). As most inherited retinal degenerations are caused by mutations found in the photoreceptor and RPE cells, subretinal injections have been used in most gene therapy studies.

Depending on the cell target, Ad, LV, and AAV have been studied. After subretinal delivery both Ad and LV transduce the RPE efficiently. Ad, however, has been associated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated removal of the transduced cells that express the encoded Ad proteins,4 leading to transient gene expression. More recently, helper-dependent Ad vectors devoid of sequences encoding viral proteins have been developed and shown to target the RPE stably.5,6 Thus far, photoreceptor transduction remains elusive with Ad and LV vectors despite the great diversity of new serotypes and pseudotypes tested.7 Further development of Ads and discovery of new Ad serotypes might enable photoreceptor transduction with Ad8–10 in the future. If Ad can be modified to enable photoreceptor transduction, its large carrying capacity will be of interest for treating inherited retinal degenerations such as Usher syndrome (USH), in which the genes involved have very long open reading frames. LVs are an alternative to Ad. LV-based vectors are deleted of all viral genes and, thus, do not activate the immune system.11,12 However, LVs are integrating vectors, and this implies the possibility of insertional mutagenesis, potential mobilization in human cells, and vector replication.12 Most studies showed that subretinal delivery of LVs leads to efficient RPE transduction,13–15 but postmitotic photoreceptors seem refractory to transduction by LV.16,17 The development of the nonprimate equine infectious anemia virus has raised hopes for overcoming this limitation.18 This has been the basis for the ongoing clinical trials to treat exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01301443), Stargardt disease (STGD) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01367444), and USH type IB (USH1B) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01505062), using this vector. These clinical trials are discussed below. However, the transduction of mature neural retina remains a fundamental limitation of LVs and Ads as vectors for retinal gene therapy. This is one of the reasons why AAV has been the preferred vector of choice for gene delivery to the retina. AAVs have an excellent safety profile (lack of pathogenicity and low immunogenicity) and provide long-lasting transgene expression (for a review, see Colella and Auricchio19). AAV has the additional advantage of being a small virus, which can diffuse easily across biological barriers and within neural tissue. It is the only vector that can provide gene delivery to the inner retina after intravitreal delivery.20–22 Although the small size of the AAV particle is an advantage, it is also its weakness: the 25-nm AAV particles can package only 4.7 kb of genetic material, limiting its application in some diseases. Nevertheless, AAV has yet another advantage that has contributed to its development as a gene delivery vehicle: it is a nonenveloped virus and its capsid can be easily modified using genetic engineering techniques. As such, it has been extensively explored for its ability to target various groups of cells in the retina.23–28 As an example, it has been engineered to provide gene delivery into deeper layers of the retina after intravitreal administration, removing the need for subretinal detachment.23–25,29 One such AAV variant, called 7m8, was able to ensure efficient pan-retinal delivery of the therapeutic gene from the vitreous, with long-term histological and functional rescue of X-linked retinoschisis and Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) phenotypes in mice and provided superior retinal gene delivery in nonhuman primates.25

Past studies have pointed toward the higher efficiency of viral versus nonviral vehicles30 for retinal gene delivery. However, reports on nanoparticle-mediated retinal gene therapy showed an improvement compared with previous studies with nonviral agents.31 Nonviral (lipid or nanoparticle) carriers provide a complementary approach (for a review, see Adijanto and Naash32). These include naked DNA, DNA-encapsulating liposomes, and compacted-DNA nanoparticles (cationic liposome/DNA complexes). In general, they allow transfection of cells with larger pieces of DNA and carry lower risk of immune responses associated with viral gene delivery.33,34 However, lack of long-term gene expression is a major limitation of such vectors. For example, clinical trials using polyethylene glycol-substituted 30-mer lysine peptide-based nanoparticles and lipid-mediated vectors to deliver therapeutic genes to the nasal mucosa of patients with cystic fibrosis reported no detectable gene expression, although vector DNA was detectable for at least 2 weeks.35 Although their use has been limited thus far, their additional development for increased efficacy could make them versatile tools for gene delivery in the years to come.

The first clinical success of retinal gene therapy

Encouraging results from animal studies (mouse, rat, dog) showed that AAV-mediated gene therapy has the potential to slow down or reverse vision loss, and paved the way toward first application in humans. The first gene therapy success has been documented with the clinical trials for LCA, a severe retinal dystrophy characterized by visual impairment from birth.36 It is caused by mutations in at least 19 different genes (22 mapped and identified genes; see the Retinal Information Network [http://www.retnet.org], accessed January 20, 2016). Mutations in the gene encoding the RPE-specific protein RPE65 appear to account for about 5–10% of LCA cases.37,38 For this specific form of human LCA (LCA2), the first clinical trial of gene replacement therapy started in 2007 at (1) the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital (London, UK), (2) the Scheie Center for Hereditary Retinal Degenerations, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) and the University of Florida College of Medicine (Gainesville, FL), and (3) the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania, and the Second University of Naples and the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM) (Naples, Italy). Patients received a single subretinal injection of AAV2 vector carrying the RPE65 gene in the most affected eye. In 2008, the independently working groups reported the first safety and efficacy results of the AAV-mediated RPE65 transfer.39–41 In addition to excellent safety, improvements in some measures of vision (including best-corrected visual acuity, kinetic visual field, nystagmus testing, pupillary light reflex, microperimetry, dark-adapted perimetry, dark-adapted full-field sensitivity testing) have been demonstrated in these phase I clinical trials. Since then, results of follow-up and dose-escalation studies have been published40,42–46 and confirmed the feasibility and benefits of gene therapy in retinal degenerative diseases. In view of these encouraging results, readministration of RPE65 gene-based treatment was performed for the first time in the contralateral eye of adult patients with LCA, 3 years after the initial gene therapy administration.47 This intervention led to positive improvements in the second eye. In addition to improved visual outcomes, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies provided evidence that the human visual cortex responds to gene therapy-mediated recovery of retinal function.45 fMRI evaluation found correlation between preserved light sensitivity and a cortical projection zone of pseudo-foveas developed in treated retinal regions (observed 9–12 months after therapy and persisting for up to 6 years).48 Multimodal noninvasive neuroimaging has revealed long-term structural plasticity in the visual pathways of patients with LCA who received single-eye gene augmentation therapy.49 It has been suggested that the visual experience gained by gene therapy may promote reorganization and maturation of synaptic connectivity in the visual pathways of the treated eye in patients with LCA. Today, retinal gene therapy has entered into phase III (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00999609). At least 24 patients with LCA (age, 3 years or older), will be recruited at either the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia or the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). They will receive a subretinal administration of AAV2-RPE65 to both eyes. A prospective open label gene therapy (AAV4-RPE65) study for RPE65-associated retinal dystrophy was also performed and completed in the Nantes University Hospital (Nantes, France) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01496040) (results still to be published).

The initial positive results from LCA gene therapy studies were challenged by new findings. In 2013, two groups50,51 reported that early visual improvements in RPE65-treated patients with LCA persist up to 3 years, with no detectable decline in visual improvement. However, retinal degeneration continued to progress. This observation was also seen in RPE65-mutant dogs. Two years later, the New England Journal of Medicine published the long-term follow-up results of two independent studies on RPE65 gene therapy. Jacobson and colleagues (United States) described follow-up data from three RPE65-treated patients.52 The patients all had improvement in visual sensitivity in the treated region that was sustained between 1 and 3 years after gene therapy. Unexpectedly, 4.5–6 years after treatment, the areas of improved vision were found to have progressively diminished in all three patients. The authors concluded that the degeneration continued at the same rate as in untreated retina, despite the initial improvement. The study from the United Kingdom (Bainbridge and colleagues)53 involved 12 patients (in this study the fovea was also targeted in order to improve both central and extrafoveal vision). Six of these patients had improvements in visual sensitivity that peaked 6–12 months after treatment. Similarly to the U.S. study, the effect declined or was lost by 3 years postinjection. These new findings prove that at least for several years gene therapy can improve vision but also indicate that the photoreceptors continue to die after the peak improvement, regardless of treatment.

As of today, it is not clear what caused the effects of gene therapy to be transient in these two clinical studies. The study by Bainbridge and colleagues53 concluded that there is a species difference in the amount of RPE65 required to drive the visual cycle and that the demand for RPE65 in affected persons in their study was not met to the extent required for a durable, robust effect (“too little” therapeutic protein). Indeed, the demand for RPE65 is likely higher in humans than in dogs.54 Another potential culprit for the transient effects is related to the stage of the retina at the time of intervention and progressive loss of trophic support (especially regarding the cones). The study by Jacobson and colleagues52 speculated that healthier photoreceptors survived in the treated retina, whereas other, more stressed rods were already in a preapoptotic state (“at the point of no return”) and continued to die. The loss of visual function at later times after treatment is in line with this natural progression of degeneration. Furthermore, the reduction in the number of rod photoreceptors in spite of therapy may eventually have led to a loss of trophic support for the cone photoreceptors that initially responded to therapy. In both studies, there were no improvements in foveal function despite vector having been delivered to the fovea in some of the patients. The question concerning why RPE65 gene supplementation improves the function of extrafoveal, but not foveal, cones remains unresolved but might well be a long-term complication of surgery. Indeed, connections between the RPE and the cones are different in the fovea and at the periphery. Although successful results have been obtained in the macula in gene supplementation therapy for choroideremia,55,56 it has been proposed that detaching the foveal cones has detrimental consequences in LCA2.46

Whatever might be responsible for the reported transient effects, there is a clear need to improve the initial approaches. One study57 suggests, at least in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) due to mutant rod-specific cyclic GMP (cGMP) phosphodiesterase 6b (PDE6b), that photoreceptor cell death can be halted, no matter at what disease stage the gene therapeutic intervention is provided. It is unclear whether the findings of this study also apply to LCA, but it is noteworthy that with an appropriate amount of therapeutic protein delivered to all mutant cells, one can stop the course of cell loss, challenging the “point of no return” hypothesis for photoreceptor cell death. One need for refinement is to better understand the visual cycle of human foveal cones and their reaction to detachment in order to make the treatments efficacious for visual acuity. Another need, identified through structural studies in dogs and patients, would be to seek a more complete therapeutic outcome that involves both visual improvement and structural rescue. A combination gene therapy in which trophic support is provided at the same time as gene supplementation might prove most effective in the long run. Further developments in vector systems that can deliver genes to the foveal region without the need for subretinal detachment will likely be beneficial for therapeutic outcome.24,25

Implementation of gene therapy for other inherited retinal diseases

Today, gene therapy is being implemented for other retinal degenerative diseases. Positive outcomes have been published for the treatment of choroideremia, using AAV as a vector.55,56 These and other ongoing studies are discussed below. Further along in the pipeline are gene therapies for other forms of LCA caused by mutations in various genes. GUCY2D is one of the most frequently mutated genes (12%) and responsible for the LCA1 disease form.36 Studies provided evidence that AAV-mediated subretinal delivery of Gucy2e preserves photoreceptor morphology and restores retinal function in mouse models over a lifetime,58,59 suggesting that gene replacement therapy for people with the LCA1 gene could be feasible. Orphan designation (EMA/COMP/97253/2014) for the development of AAV vector serotype 8 carrying the human GUCY2D gene was granted for the treatment of LCA1.60 As mutations in GUCY2D are also associated with autosomal recessive forms of cone–rod dystrophy (reviewed in Boye et al.59), this gene replacement therapy may offer vision restoration to a larger group of patients. Although preliminary, strategies for the development of gene therapy for CEP290-associated LCA (LCA10) are also under consideration. Burnight and colleagues61 provided evidence that LV vector expressing full-length human CEP290 can correct the CEP290 disease-specific cellular phenotype in patient-derived fibroblasts, but it is not clear whether the LV-mediated approach will be able to deliver to photoreceptors in patients. Another approach might be the use of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing; this is currently being developed by Editas (Cambridge, MA). Potential treatment of LCA4 due to AIPL1 mutations is also under consideration.62 A high level of AIPL1 photoreceptor expression and no toxicity were documented in Aipl1 null mice and porcine eyes that received subretinal administration of AAV2/8-AIPL1.54 As some patients with AIPL1-associated disease have a late onset and slow progression rate, it may be a good candidate for gene augmentation therapy.63

Current clinical trials

Stargardt disease (STGD) is the most common hereditary macular dystrophy and the most common cause of central visual loss in young people. In the majority of cases (90–95%), the disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and is associated with mutations in the photoreceptor-specific ABCA4 gene (which encodes the ATP-binding cassette transporter involved in the clearance of retinoid by-products).64 Proof-of-concept studies in Abca4−/− mice65 demonstrated that subretinal administration of LV vector carrying the human ABCA4 gene was associated with reduced A2E accumulation, corrected lipofuscin levels, and improved RPE morphology and retinal function. On the basis of these findings, the first gene-based therapy clinical trial for the treatment of STGD moved into human studies. Work with SAR422459 (LV-ABCA4) is currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01367444) at the Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, OR) and the National Eye Hospital of Quinze-Vingts (Paris, France). No serious adverse events related to dose level 1 or the method of administration have been reported so far (Data Safety Monitoring Board, 2012; see http://www.oxfordbiomedica.co.uk/press-releases/oxford-biomedica-announces-positive-dsmb-review-of-ongoing-retinostat-r-and-stargen-clinical-studies/). More recently, dual AAV systems have also successfully been implemented in bringing a gene therapy solution to Stargardt disease.66 Subretinal delivery of ABCA4 via optimized DNA–nanoparticles also resulted in persistent transgene expression and significant structural and functional correction in Abca4−/− mice,31 suggesting a relevant alternative approach for ABCA4 gene delivery.

Choroideremia (CHM) is an X-linked recessive disease that leads to progressive retinal degeneration and blindness caused by mutations in the CHM gene. The first clinical trial for this monogenic retinal disorder without extraocular manifestations has been undertaken at Oxford University (Oxford, UK) to assess the safety and tolerability of the AAV2.REP1 vector administered at two different doses to the retina in 12 patients with CHM (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01461213). So far, no major safety issues have been reported55 and some improvements above baseline were reported.

X-linked retinoschisis (XLRS) is characterized by a splitting of the neurosensory retina and progressive macular atrophy. Proof of principle for gene replacement therapy (AAV8-RS1) in mouse models has been achieved for both structural and functional recovery,67 and the first gene therapy trial is now being undertaken by the Sieving laboratory (National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02416622) and by AGTC (Alachua, FL) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02416622).

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a maternally inherited disease caused by mitochondrial DNA point mutations in complex I and characterized by acute (or subacute) painless loss of central vision resulting from degeneration of the retinal ganglion cell layer and optic nerve. Replacement of normal ND4 and ND1 gene transcripts in the fibroblasts of patients harboring mutations in these genes restored electron transport chain activity, and intravitreal viral delivery of normal gene rescued vision in an animal model of LHON.68–71 First-in-human dose escalation safety studies have been completed or are ongoing in several centers (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers, NCT01267422, NCT02161380, and NCT02064569). No serious adverse reactions related to the treatment or the study procedures have been documented (Feuer et al.72 and Uretsky et al.73). Preparation for the upcoming pivotal phase III of drug development will be undertaken.

There are other examples of ongoing and completed gene therapies for retinal diseases, including Usher syndrome 1b (MYO7A) (UshStat; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01505062; the Institut de la Vision/Clinical Investigation Center at the National Eye Hospital of Quinze-Vingts and the Casey Eye Institute) and autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa caused by MERTK mutations (AAV2-VMD2-hMERTK). In 2013, an AAV vector carrying the human CNGB3 gene received orphan drug designation (EU/3/13/1099) for the treatment of achromatopsia. AGTC plans to treat both CNGB3 and CNGA3 forms of achromatopsia.

Beyond gene supplementation

Secretion of antiangiogenic factors

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most frequent cause of vision impairment among the elderly. Wet AMD accounts for 90% of AMD-related blindness in these patients. The majority of current treatments for wet AMD aim to prevent choroidal neovascularization through the delivery of antiangiogenic factors (i.e., bevacizumab [Avastin] or ranibizumab [Lucentis]). These compounds inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), which is thought to be responsible for the growth and increased permeability of new blood vessels.74 As AMD is a complex disease, it was not considered a likely candidate for gene therapy. However, the success of VEGF antagonists, which required frequent readministration, and the possibility of long-term expression of antiangiogenic molecules through AAV-mediated expression sparked interest. In two ongoing phase I clinical trials, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) and soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFLT) are being tested as potential candidates for the treatment of wet AMD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers, NCT01024998 and NCT01494805). All of the previously mentioned clinical trials are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Current clinical trials in retinal gene therapy

| Disease | Encoded gene | Protein | Cell target | Vector | Clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCA2 | RPE65 | Retinal isomerase RPE65 | RPE | AAV | NCT00516477 |

| NCT00749957 | |||||

| NCT00821340 | |||||

| NCT01208389 | |||||

| NCT00999609 | |||||

| NCT00481546 | |||||

| NCT00643747 | |||||

| Choroideremia | CHM1 | REP1 | RPE + choroid | AAV | NCT02077361 |

| NCT01461213 | |||||

| NCT02341807 | |||||

| NCT02553135 | |||||

| NCT02407678 | |||||

| Usher syndrome | MYO7A | Myosin 7a | PR | Lentivirus | NCT01505062 |

| NCT02065011 | |||||

| Stargardt disease | ABCA4 | Photoreceptor-specific adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter | PR | Lentivirus | NCT01367444 |

| NCT01736592 | |||||

| LHON | ND4 | NADH dehydrogenase | RGC | AAV | NCT01267422 |

| NCT02064569 | |||||

| NCT02161380 | |||||

| arRP | MERTK | MER tyrosine kinase receptor | RPE | AAV | NCT01482195 |

| Retinoschisis | RS1 | Retinoschisin | PR | AAV | NCT02317887 |

| NCT02416622 | |||||

| AMD | FLT1 | Soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase receptor | Soluble | AAV |

NCT01494805 NCT01024998 |

| Endostatin and angiostatin | Lentivirus | NCT01301443 | |||

| PLG and COL18A1 | Angiostatin and endostatin | Soluble | Lentivirus |

NCT01301443 NCT01678872 |

AAV, adeno-associated virus; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; arRP, autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa; LCA2, Leber congenital amaurosis type 2; LHON, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; PR, photoreceptor; REP1, Rab escort protein 1; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Neuroprotection

Neuroprotective agents can prevent and reverse oxidative stress and its damaging effects, and restore normal cell function. One retina-specific trophic factor, called rod-derived cone viability factor (RdCVF), has been shown to induce cone survival and functional rescue in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa (RP),75,76 in a gene-independent manner. AAV-RdCVF prolonged cone survival and function in RP mice.77 It has been suggested as a particularly well-suited therapy for preventing secondary cone degeneration in rod–cone dystrophies and for treating RP at a stage of night blindness associated with moderate central visual impairment (stages I and II in Fig. 1).78 One study showed that retinal cone survival promoted by RdCVF is associated with accelerated glucose entry into photoreceptors and enhanced aerobic glycolysis, uncovering an entirely novel mechanism of neuroprotection.79 Structural and functional rescue in retinal diseases has also been reported for intraocular gene transfer of other vector-delivered neuroprotective factors in preclinical animal models, for example, ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF),80–82 PEDF,83 and glial-derived neurotrophic factor.84 Although promising, no clinical trials have thus far been conducted in which trophic factors are provided in the form of gene therapy. Encapsulated cell technology has been used in ongoing and completed clinical trials to provide neuroprotection through CNTF secretion in atrophic macular degeneration (NCT00447954), retinitis pigmentosa (NCT00447980, NCT00447993), achromatopsia (NCT01648452), macular telangiectasia (NCT01949324), and glaucoma (NCT01408472).

Once photoreceptors stop capturing light: What next?

When photoreceptor degeneration is too advanced (stages III and IV in Fig. 1), patients will have little chance to benefit from gene replacement therapy or neuroprotection. In these cases, new strategies for vision restoration should be explored. These include retinal prostheses—designed to stimulate responses from surviving inner retinal neurons85–87—or optogenetics, a technique allowing control of neural activity via genetic introduction of light-sensitive proteins such as channelrhodopsin and halorhodopsin.88–91 Vertebrate opsins such as melanopsin92 and rhodopsin,93,94 as well as a chimera between melanopsin and mGluR6 receptor,95 have also been used for vision restoration in late-stage RP. The common feature between these approaches is the use of a gene encoding a light-sensitive protein that transforms light-insensitive cells of the retina into artificial photoreceptors. This strategy has enjoyed success in preclinical studies, in a number of rodent models of inherited retinal disease. At present, optogenetics is being moved toward the clinic by several companies (GenSight Biologics [Paris, France] and RetroSense Therapeutics [Ann Arbor, MI]) that have shown interest in the use of microbial opsins for vision restoration. Evaluation of candidate patients for optogenetic therapy is also underway.96

Cell Therapy

Cell therapy represents an alternative to repair the degenerated retina. Transplantation of retinal cells has been historically viewed as a potential vision restoration strategy for retinal degenerative diseases, particularly in disease stages associated with significant cell damage (stages II and IV in Fig. 1). This therapeutic approach aims at replacing the lost retinal cells using stem cells, progenitor cells, and mature neural retinal cells. The main advantage of cell therapies as a source for regenerative therapy is that they are mutation-independent and can be used in a wide range of retinal degenerative conditions. Patients with retinal degeneration typically lose RPE cells, photoreceptors, or both. Therefore, two main cell sources can be considered: first, RPE cells to replace dysfunctional or degenerated RPE and to prevent photoreceptor cell loss and, second, photoreceptor precursors to repair the degenerating neural retina.

Several novel stem cell-based therapies addressing inherited and age-related retinal degenerative diseases are currently under development and/or clinical evaluation. They are based on a significant body of evidence showing that human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) can be expanded indefinitely in culture and can be used as an unlimited source of retinal cells (RPE cells, photoreceptors, and retinal ganglion cells) for the treatment of retinal degeneration. Since their first establishment in 1981,97 human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have been intensively studied by many groups worldwide. Furthermore, the discovery that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into an ESC-like pluripotent state, known as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), offers the same applications in regenerative medicine, bypassing human ESCs, the use of which has major ethical restrictions. After reprogramming mouse somatic cells into iPSCs,98 the Yamanaka group was able to reprogram human fibroblasts into iPSCs by overexpressing the four transcription factors OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, and C-MYC.99 Today, these two types of PSCs represent major cell sources in regenerative medicine.

Various groups have reported encouraging morphological and functional results in animal models of retinal degeneration after transplantation of RPE cells, retinal progenitor cells, photoreceptor precursors, or full-thickness retinal sheets (for reviews, see References 100–103). Integration into the host retina and reconstruction of functional neural circuitry have been seen as major hurdles for successful cell transplantation. For these reasons, the most advanced studies today concern the transplantation of RPE.

Cell transplantation using human PSCs

Human PSCs for RPE cell replacement

At present, the most plausible approach for the development of cell therapy for macular degeneration consists of replacement of lost or dysfunctional RPE with healthy RPE cells, which are essential for photoreceptor shedding, maintenance, and survival. Indeed, various groups have already demonstrated that human PSCs can be differentiated into RPE cells with morphological and functional characteristics similar to those of human RPE cells (for review, see Leach and Clegg104).

The first-in-human safety and tolerability prospective clinical trial to evaluate subretinal injection of human ESC-derived RPE cells (specifically line MA09-hRPE) in patients with dry AMD and STGD is currently underway. It has been sponsored by Ocata Therapeutics (Marlborough, MA; formerly Advanced Cell Technology) and conducted at four centers in the United States: Jules Stein Eye Institute (University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA), Wills Eye Hospital (Philadelphia, PA), Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (Miami, FL), and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (Boston, MA). Doses of 50,000, 100,000, and 150,000 cells (cell suspensions) have been administered to one eye of each of 9 patients with dry AMD and 9 patients with STGD (3 patients in each cohort). Patches of increasing subretinal pigmentation consistent with the transplanted RPE cells were documented in 13 of the 18 patients (72%), but were not correlated with visual acuity improvement. Follow-up testing showed that 10 of 18 treated eyes had substantial improvements in the first year after transplantation. Stable improvement of visual acuity over 22 months was reported in 7 patients, but decreased by more than 10 letters in one patient. Untreated eyes did not show similar visual improvements, but no correlations between visual acuity improvement and the number of transplanted cells was reported.105,106 Median follow-up at 22 months suggested no major safety concerns (no signs of hyperproliferation, tumorigenicity, ectopic tissue formation, or apparent rejection). Adverse events were associated with surgery and immunosuppressive treatment but were not considered related to the human ESC-derived cells.105,106 These results provide evidence of the medium- to long-term safety, graft survival, and biological activity on injection of human ESC-derived RPE cell suspensions into patients with macular degeneration.

To date, at least 15 ongoing clinical trials are registered at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) of the World Health Organization to test stem cell-based replacement therapies for treatment of retinal dystrophies (Table 1). Some examples include the phase I/II clinical trials with human ESC-derived RPE cells sponsored by CHA Biotech (Seoul, South Korea), Cell Cure Neurosciences (Jerusalem, Israel), and Pfizer (Tadworth, U.K.).107 The London Project to Cure Blindness (sponsored by Pfizer) will insert a monolayer sheet of human ESC-derived RPE cells cultured on polyester membrane into 10 patients with wet AMD and rapid recent vision decline. This polyester matrix has been reported to maintain polarized human RPE cells after grafting into the rabbit subretinal space.108 Similarly, the California Project to Cure Blindness will use a differentiated polarized monolayer of RPE cells attached to a nondegradable Parylene membrane possessing the permeability properties of a healthy Bruch's membrane. A human phase I/II clinical trial will evaluate the safety and tolerability of this tissue-engineering product (TEP) in patients with gyrate atrophy.101,109 The proof of concept with this TEP has been reported in RCS rats and in Yucatan pigs.101,110

As human iPSCs can be obtained directly from the patient, they have the advantage of being autologous and therefore less immunogenic than ESCs for future cell transplantation studies. In this context, the Takahashi group at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology (Kobe, Japan) is currently setting up human clinical trials with human iPSC-derived RPE for the treatment of AMD. On the basis of safety studies in rodents and monkeys, this group started to implant a sheet of RPE differentiated from iPSCs previously derived from the fibroblasts of one patient with an exudative form of AMD.111 This pilot clinical study is assessing the safety (i.e., the potential to induce immune reactions, cancerous growth) and feasibility of the transplantation of autologous iPSCs. No further details have yet been reported.

Human PSCs for photoreceptor cell replacement

Whereas RPE replacement alone may be used for specific disease indications, transplantation of photoreceptors—as retinal sheet or as suspension of dissociated cells—is required after extensive photoreceptor degeneration. Retinal neurons, including photoreceptors, have been generated from human iPSCs by various laboratories worldwide (for reviews, see Borooah et al.112 and Chen et al.113), but so far cell transplantation to restore neural retina is restricted to animal models. Prior groundbreaking studies in mice revealed that the ontogenetic stage of transplanted cells is crucial for successful integration into the adult host retina and recovery of vision.114–116 Indeed, the Ali group demonstrated in mice that only stage-specific photoreceptor precursors, corresponding to postmitotic committed photoreceptors, are able to efficiently integrate into the degenerating retina, differentiate into mature photoreceptors, form synaptic connections, and possibly lead to recovery of visual function.114,116 Furthermore, a direct relationship between cellular integration and functional recovery has been clearly established.116 From these pioneering studies emerged the importance of identifying the in vitro equivalent of postmitotic postnatal photoreceptor precursors derived from PSCs. These photoreceptor precursor cells (PPCs), derived from mouse ESCs in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) allowed tracing of the photoreceptor lineage, have been successfully differentiated and transplanted into the mouse retina.117,118 To date only one study has reported transplantation of photoreceptors derived from human PSCs in mouse models of photoreceptor degeneration.119 After subretinal transplantation of virally labeled GFP-positive photoreceptors, Lamba and colleagues119 demonstrated cell integration into the remaining neural retina and partial restoration of visual function. The use of fluorescent reporter cell lines to isolate photoreceptor precursors is not compatible with future clinical applications. The surface antigen CD73, previously used to isolate precursors of photoreceptors from mouse postnatal retina for transplantation,120,121 could be a promising candidate. Our group demonstrated that photoreceptor precursors differentiated from human iPSCs specifically expressed CD73.122 On the basis of data with mouse ESCs, the use of a five-cell surface biomarker panel (CD73, CD133, CD47, and CD24 [positive] and CD15 [negative]) could be used to improve the isolation of photoreceptor precursors.123

In the case of severe degenerations and loss of the outer nuclear layer (ONL), transplantation of retinal sheets rather than dissociated cells could be required. The Takahashi group transplanted mouse PSC-derived retinal sheets containing a defined ONL into rd1 mice (a model of advanced retinal degeneration associated with lost ONL) and observed host–graft synaptic connections.124 The development of innovative protocols allowing the generation of neuroretinal structures from human PSCs122,125,126 will be helpful in assessing the capacity of human retinal sheet to make contact with the recipient retina after subretinal transplantation.

Alternative source of human cells for retinal cell replacement

It has been reported that many types of stem cells, such as neural stem cells (NSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), possess inherent neuroprotective properties when transplanted into animal models of retinal disease (for review, see Bull and Martin127). Even though the generation of new retinal cells directly derived from MSCs and NSCs remains unlikely, paracrine effects (such as antiapoptotic and antiinflammatory signaling) could explain how these cells contribute to prolonged retinal cell survival. StemCells (Newark, CA) is sponsoring a study to determine the safety and potential benefits of subretinal injection of human NSCs into patients with geographic atrophy due to AMD. The trial is based on findings that subretinal transplantation of human NSCs (grown as neurospheres) derived from the fetal brain can partially protect against photoreceptor degeneration and preserve the visual function in RCS rats.128 Early results at 6 months' follow-up showed maintenance or improvement in best corrected visual acuity and contrast sensitivity with no safety concerns.129 Autologous bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMSCs) are under evaluation in patients with AMD in phase I/II clinical trials in southern Florida and California and in various locations worldwide (Table 2). Safety studies involving the subretinal administration of human umbilical tissue-derived cells (UTCs; CNTO 2476) are currently being performed in patients with advanced RP and in subjects with visual acuity impairment associated with geographic atrophy secondary to AMD. No clinical data have yet been reported. A similar concept is being implemented in the RP project of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (Oakland, CA), in conjunction with jCyte (Newport Beach, CA). They will explore the safety of intravitreal injection, into patients with RP, of human retinal progenitor cells obtained from fetal retina and expanded in culture. It is expected that these cells will not only exert neurotrophic support but also will differentiate and integrate into the retina.

Table 2.

Clinical trials using stem cell-based therapies in the retina: initiated or completed as of November 2015

| Sponsor (location) | Identifiers | Cell source | Target disease | Delivery method | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocata Therapeutics (USA, UK) | NCT01345006/NCT02445612 | hESC-derived RPE cells | Stargardt disease | Subretinal | I/II |

| NCT01344993/NCT02463344/NCT02563782 | hESC-derived RPE cells | Dry AMD | Subretinal | I/II and II | |

| NCT02122159 | hESC-derived RPE cells | Myopic macular degeneration | Subretinal | I/II | |

| CHA Biotech (South Korea) | NCT01674829 | hESC-derived RPE cells | Dry AMD | Subretinal | I/II |

| Cell Cure Neuroscience (Israel) | NCT02286089 | hESC-derived RPE cells | Dry AMD | Subretinal | I/IIa |

| Pfizer/University College London (UK) | NCT01691261 | hESC-derived RPE cell sheets | Wet AMD | Subretinal | I |

| RIKEN Institute (Japan) | UMIN000011929 | hiPSC-derived RPE cell sheets | Wet AMD | Subretinal | I |

| jCyte (USA) | NCT02320812 | hRPCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Subretinal | I |

| StemCells (USA) | NCT01632527 | hNSCs | AMD | Subretinal | I |

| NCT02467634 | hNSCs | GA and AMD | Subretinal | II | |

| Retina Associates of South Florida (USA) | NCT01920867 | hBMSCs | AMD, hereditary retinal dystrophies and glaucoma | Intravitreal and subretinal | N/A |

| University of São Paulo (Brazil) | NCT01518127 | hBMSCs | AMD and Stargardt disease | Intravitreal | I |

| NCT01068561/NCT01560715 | hBMSCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Intravitreal | I | |

| University of California Davis (USA) | NCT01736059 | hBMSCs | AMD, diabetic retinopathy, retina vein occlusion, retinitis pigmentosa, hereditary macular degeneration | Intravitreal | I |

| Red de Terapia Celular (Spain) | NCT02280135 | hBMSCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Intravitreal | I |

| Chaitanya Hospital (India) | NCT01914913 | hBMSCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Intravitreal | I/II |

| Al-Azhar University (Egypt) | NCT02016508 | hBMSCs | AMD | Intravitreal | I/II |

| Mahidol University (Thailand) | NCT01531348 | hBM-derived MSCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Intravitreal | I |

| Janssen Research & Development (USA) | NCT00458575 | hUTSCs | Retinitis pigmentosa | Subretinal | I |

| NCT01226628 | hUTSCs | AMD | Subretinal | I/II |

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; GA, gyrate atrophy; hBMSCs, human bone marrow-derived stem cells; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; hiPSCs, human induced pluripotent stem cells; hNSCs, human neural stem cells; hRPCs, human retinal progenitor cells; hUTSCs, human umbilical tissue-derived stem cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; N/A, not available; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Another type of cell-based therapy for retinal degeneration approaching clinical translation is the use of human cells to provide neurotrophic factors in order to improve the survival of photoreceptors and their function. An example in this respect is the implantable cell-encapsulation device NT-501 developed by Neurotech Pharmaceuticals (Cumberland, RI)130 that consists of a human RPE cell line transfected with a plasmid encoding CNTF encapsulated within a semipermeable polymer membrane and supportive matrices. A phase I clinical trial indicated that CNTF is safe for the human retina even with severely compromised photoreceptors and may have application beyond disease caused by genetic mutations.131 At present, the device is under evaluation in phase II studies for the treatment of dry AMD and RP.

Challenges

Although stem cell therapy carries great potential for the treatment of retinal degeneration, its advancement to clinical translation faces multiple challenges. Among the most important are health and ethical issues associated with the nature of most stem cell types, such as risks of tumorigenesis associated with reprogramming and immunogenic responses. Risks associated with the surgery and microbiological safety can also be limiting factors for the use of stem cells. The type and number of cells needed for effective treatment, transplanted cell survival, and the functional outcomes remain questions of major importance for successful stem cell-based therapies in the clinic. Finally, production and delivery of clinical-grade stem cells involve unique regulatory and quality control requirements that need to be clearly established.

Concluding Remarks

Gene and cell therapies opened new doors in the treatment of currently incurable retinal degenerative disorders and promise to be the therapeutics of the future. To accelerate the advancement of this innovative field, expert groups have proposed key steps and recommendations. These recommendations address the most pressing needs for the development and delivery of effective treatments for retinal dystrophies in the next decade. The meeting of the National Eye Institute in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health Center for Regenerative Medicine132 and the Monaciano Symposium133 strongly recommended collaborative translational efforts, including the creation of international databases of correlative phenotype–genotype information, standardized protocols and outcome measures, common regulatory protocols, and technology transfer mechanisms.134 There is a strong conviction that efficient partnerships between academia, industry, funding agencies, and policy makers are needed to translate laboratory discovery into the development of innovative gene and cell therapeutic strategies for the treatment of retinal degeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), Pierre et Marie Curie Université (UPMC), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) (CD-CL-0808-0466-CHNO), and the French State program Investissements d'Avenir managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (LABEX LIFESENSES: ANR-10-LABX-65).

Author Disclosure

D.D. is a consultant for GenSight Biologics. O.G. and K.M. have no competing financial interests. J.-A.S. is a founder and consultant for Pixium Vision and GenSight Biologics, and a consultant for Sanofi-Fovea, Genesignal, and Vision Medicines.

References

- 1.Streilein JW. Ocular immune privilege: therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:879–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspi RR. A look at autoimmunity and inflammation in the eye. J Clin Invest 2010;120:3073–3083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahel JA, and Roska B. Gene therapy for blindness. Annu Rev Neurosci 2013;36:467–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichel MB, Ali RR, Thrasher AJ, et al. . Immune responses limit adenovirally mediated gene expression in the adult mouse eye. Gene Ther 1998;5:1038–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochanek S. High-capacity adenoviral vectors for gene transfer and somatic gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 1999;10:2451–2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreppel F, Luther TT, Semkova I, et al. . Long-term transgene expression in the RPE after gene transfer with a high-capacity adenoviral vector. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:1965–1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puppo A, Cesi G, Marrocco E, et al. . Retinal transduction profiles by high-capacity viral vectors. Gene Ther 2014;21:855–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Seggern DJ, Aguilar E, Kinder K, et al. . In vivo transduction of photoreceptors or ciliary body by intravitreal injection of pseudotyped adenoviral vectors. Mol Ther 2003;7:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashman SM, McCullough L, and Kumar-Singh R. Improved retinal transduction in vivo and photoreceptor-specific transgene expression using adenovirus vectors with modified penton base. Mol Ther 2007;15:1640–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweigard JH, Cashman SM, and Kumar-Singh R. Adenovirus vectors targeting distinct cell types in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:2219–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett J. Immune response following intraocular delivery of recombinant viral vectors. Gene Ther 2003;10:977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pauwels K, Gijsbers R, Toelen J, et al. . State-of-the-art lentiviral vectors for research use: risk assessment and biosafety recommendations. Curr Gene Ther 2009;9:459–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auricchio A, Kobinger G, Anand V, et al. . Exchange of surface proteins impacts on viral vector cellular specificity and transduction characteristics: the retina as a model. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:3075–3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duisit G, Conrath H, Saleun S, et al. . Five recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus pseudotypes lead to exclusive transduction of retinal pigmented epithelium in rat. Mol Ther 2002;6:446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kachi S, Binley K, Yokoi K, et al. . Equine infectious anemia viral vector-mediated codelivery of endostatin and angiostatin driven by retinal pigmented epithelium-specific VMD2 promoter inhibits choroidal neovascularization. Hum Gene Ther 2009;20:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bemelmans AP, Bonnel S, Houhou L, et al. . Retinal cell type expression specificity of HIV-1-derived gene transfer vectors upon subretinal injection in the adult rat: influence of pseudotyping and promoter. J Gene Med 2005;7:1367–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balaggan KS, Binley K, Esapa M, et al. . Stable and efficient intraocular gene transfer using pseudotyped EIAV lentiviral vectors. J Gene Med 2006;8:275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binley K, Widdowson P, Loader J, et al. . Transduction of photoreceptors with equine infectious anemia virus lentiviral vectors: safety and biodistribution of StarGen for Stargardt disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:4061–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colella P, and Auricchio A. AAV-mediated gene supply for treatment of degenerative and neovascular retinal diseases. Curr Gene Ther 2010;10:371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peeters L, Sanders NN, Braeckmans K, et al. . Vitreous: a barrier to nonviral ocular gene therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:3553–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg KP, Geller SF, Schaffer DV, et al. . Targeted transgene expression in Muller glia of normal and diseased retinas using lentiviral vectors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:1844–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalkara D, Kolstad KD, Caporale N, et al. . Inner limiting membrane barriers to AAV-mediated retinal transduction from the vitreous. Mol Ther 2009;17:2096–2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrs-Silva H, Dinculescu A, Li Q, et al. . High-efficiency transduction of the mouse retina by tyrosine-mutant AAV serotype vectors. Mol Ther 2009;17:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay CN, Ryals RC, Aslanidi GV, et al. . Targeting photoreceptors via intravitreal delivery using novel, capsid-mutated AAV vectors. PLoS One 2013;8:e62097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalkara D, Byrne LC, Klimczak RR, et al. . In vivo-directed evolution of a new adeno-associated virus for therapeutic outer retinal gene delivery from the vitreous. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:189ra76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cronin T, Vandenberghe LH, Hantz P, et al. . Efficient transduction and optogenetic stimulation of retinal bipolar cells by a synthetic adeno-associated virus capsid and promoter. EMBO Mol Med 2014;6:1175–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scalabrino ML, Boye SL, Fransen KM, et al. . Intravitreal delivery of a novel AAV vector targets ON bipolar cells and restores visual function in a mouse model of complete congenital stationary night blindness. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:6229–6239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandenberghe LH, and Auricchio A. Novel adeno-associated viral vectors for retinal gene therapy. Gene Ther 2012;19:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyd RF, Sledge DG, Boye SL, et al. . Photoreceptor-targeted gene delivery using intravitreally administered AAV vectors in dogs. Gene Ther (in press) doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrieu-Soler C, Bejjani RA, de Bizemont T, et al. . Ocular gene therapy: a review of nonviral strategies. Mol Vis 2006;12:1334–1347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han Z, Conley SM, Makkia R, et al. . Comparative analysis of DNA nanoparticles and AAVs for ocular gene delivery. PLoS One 2012;7:e52189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adijanto J, and Naash MI. Nanoparticle-based technologies for retinal gene therapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2015;95:353–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han Z, Conley SM, Makkia RS, et al. . DNA nanoparticle-mediated ABCA4 delivery rescues Stargardt dystrophy in mice. J Clin Invest 2012;122:3221–3226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Z, Banworth MJ, Makkia R, et al. . Genomic DNA nanoparticles rescue rhodopsin-associated retinitis pigmentosa phenotype. FASEB J 2015;29:2535–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konstan MW, Davis PB, Wagener JS, et al. . Compacted DNA nanoparticles administered to the nasal mucosa of cystic fibrosis subjects are safe and demonstrate partial to complete cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator reconstitution. Hum Gene Ther 2004;15:1255–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.den Hollander AI, Roepman R, Koenekoop RK, et al. . Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog Retin Eye Res 2008;27:391–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morimura H, Fishman GA, Grover SA, et al. . Mutations in the RPE65 gene in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa or Leber congenital amaurosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:3088–3093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Wang H, Peng J, et al. . Mutation survey of known LCA genes and loci in the Saudi Arabian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:1336–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, et al. . Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2240–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, et al. . Treatment of Leber congenital amaurosis due to RPE65 mutations by ocular subretinal injection of adeno-associated virus gene vector: short-term results of a phase I trial. Hum Gene Ther 2008;19:979–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. . Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2231–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Boye SL, et al. . Human gene therapy for RPE65 isomerase deficiency activates the retinoid cycle of vision but with slow rod kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:15112–15117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maguire AM, High KA, Auricchio A, et al. . Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2009;374:1597–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simonelli F, Maguire AM, Testa F, et al. . Gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis is safe and effective through 1.5 years after vector administration. Mol Ther 2010;18:643–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashtari M, Cyckowski LL, Monroe JF, et al. . The human visual cortex responds to gene therapy-mediated recovery of retinal function. J Clin Invest 2011;121:2160–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Ratnakaram R, et al. . Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis caused by RPE65 mutations: safety and efficacy in 15 children and adults followed up to 3 years. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:9–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennett J, Ashtari M, Wellman J, et al. . AAV2 gene therapy readministration in three adults with congenital blindness. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:120ra15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cideciyan AV, Aguirre GK, Jacobson SG, et al. . Pseudo-fovea formation after gene therapy for RPE65-LCA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:526–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashtari M, Zhang H, Cook PA, et al. . Plasticity of the human visual system after retinal gene therapy in patients with Leber's congenital amaurosis. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:296ra110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Testa F, Maguire AM, Rossi S, et al. . Three-year follow-up after unilateral subretinal delivery of adeno-associated virus in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis type 2. Ophthalmology 2013;120:1283–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG, Beltran WA, et al. . Human retinal gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis shows advancing retinal degeneration despite enduring visual improvement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E517–E525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Roman AJ, et al. . Improvement and decline in vision with gene therapy in childhood blindness. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1920–1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bainbridge JW, Mehat MS, Sundaram V, et al. . Long-term effect of gene therapy on Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1887–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Testa F, Surace EM, Rossi S, et al. . Evaluation of Italian patients with Leber congenital amaurosis due to AIPL1 mutations highlights the potential applicability of gene therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:5618–5624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacLaren RE, Groppe M, Barnard AR, et al. . Retinal gene therapy in patients with choroideremia: initial findings from a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet 2014;383:1129–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scholl HP, and Sahel JA. Gene therapy arrives at the macula. Lancet 2014;383:1105–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koch SF, Tsai YT, Duong JK, et al. . Halting progressive neurodegeneration in advanced retinitis pigmentosa. J Clin Invest 2015;125:3704–3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boye SE, Boye SL, Pang J, et al. . Functional and behavioral restoration of vision by gene therapy in the guanylate cyclase-1 (GC1) knockout mouse. PLoS One 2010;5:e11306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boye SL, Peshenko IV, Huang WC, et al. . AAV-mediated gene therapy in the guanylate cyclase (RetGC1/RetGC2) double knockout mouse model of Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:189–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manfredi A, Marrocco E, Puppo A, et al. . Combined rod and cone transduction by adeno-associated virus 2/8. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:982–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burnight ER, Wiley LA, Drack AV, et al. . CEP290 gene transfer rescues Leber congenital amaurosis cellular phenotype. Gene Ther 2014;21:662–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan MH, Smith AJ, Pawlyk B, et al. . Gene therapy for retinitis pigmentosa and Leber congenital amaurosis caused by defects in AIPL1: effective rescue of mouse models of partial and complete Aipl1 deficiency using AAV2/2 and AAV2/8 vectors. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:2099–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, et al. . Human retinal disease from AIPL1 gene mutations: foveal cone loss with minimal macular photoreceptors and rod function remaining. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun H, and Nathans J. ABCR: rod photoreceptor-specific ABC transporter responsible for Stargardt disease. Methods Enzymol 2000;315:879–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kong J, Kim SR, Binley K, et al. . Correction of the disease phenotype in the mouse model of Stargardt disease by lentiviral gene therapy. Gene Ther 2008;15:1311–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trapani I, Toriello E, de Simone S, et al. . Improved dual AAV vectors with reduced expression of truncated proteins are safe and effective in the retina of a mouse model of Stargardt disease. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:6811–6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ou J, Vijayasarathy C, Ziccardi L, et al. . Synaptic pathology and therapeutic repair in adult retinoschisis mouse by AAV-RS1 transfer. J Clin Invest 2015;125:2891–2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonnet C, Augustin S, Ellouze S, et al. . The optimized allotopic expression of ND1 or ND4 genes restores respiratory chain complex I activity in fibroblasts harboring mutations in these genes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1783:1707–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ellouze S, Augustin S, Bouaita A, et al. . Optimized allotopic expression of the human mitochondrial ND4 prevents blindness in a rat model of mitochondrial dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet 2008;83:373–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cwerman-Thibault H, Augustin S, Lechauve C, et al. . Nuclear expression of mitochondrial ND4 leads to the protein assembling in complex I and prevents optic atrophy and visual loss. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2015;2:15003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chadderton N, Palfi A, Millington-Ward S, et al. . Intravitreal delivery of AAV-NDI1 provides functional benefit in a murine model of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21:62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feuer WJ, Schiffman JC, Davis JL, et al. . Gene therapy for Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: initial results. Ophthalmology (in press) doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uretsky S, Sahel JA, Galy A, et al. . A recombinant AAV2/2 carrying the wild-type ND4 gene for the treatment of LHON: preliminary results of a first-in-man study and upcoming pivotal efficacy trials [abstract]. Presented at the 12th International Symposium on Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics (ISOPT Clinical), Berlin, Germany, July 9–12, 2015 Available from: http://events.eventact.com/windman/16720/ISOPT_Clinical_abstract_and_program_book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 74.Folk JC, and Stone EM. Ranibizumab therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1648–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leveillard T, Mohand-Said S, Lorentz O, et al. . Identification and characterization of rod-derived cone viability factor. Nat Genet 2004;36:755–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Y, Mohand-Said S, Danan A, et al. . Functional cone rescue by RdCVF protein in a dominant model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2009;17:787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Byrne LC, Dalkara D, Luna G, et al. . Viral-mediated RdCVF and RdCVFL expression protects cone and rod photoreceptors in retinal degeneration. J Clin Invest 2015;125:105–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leveillard T, and Sahel JA. Rod-derived cone viability factor for treating blinding diseases: from clinic to redox signaling. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:26ps16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ait-Ali N, Fridlich R, Millet-Puel G, et al. . Rod-derived cone viability factor promotes cone survival by stimulating aerobic glycolysis. Cell 2015;161:817–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Komaromy AM, Rowlan JS, Corr AT, et al. . Transient photoreceptor deconstruction by CNTF enhances rAAV-mediated cone functional rescue in late stage CNGB3-achromatopsia. Mol Ther 2013;21:1131–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.MacLaren RE, Buch PK, Smith AJ, et al. . CNTF gene transfer protects ganglion cells in rat retinae undergoing focal injury and branch vessel occlusion. Exp Eye Res 2006;83:1118–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lipinski DM, Barnard AR, Singh MS, et al. . CNTF gene therapy confers lifelong neuroprotection in a mouse model of human retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2015;23:1308–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haurigot V, Villacampa P, Ribera A, et al. . Long-term retinal PEDF overexpression prevents neovascularization in a murine adult model of retinopathy. PLoS One 2012;7:e41511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dalkara D, Kolstad KD, Guerin KI, et al. . AAV mediated GDNF secretion from retinal glia slows down retinal degeneration in a rat model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2011;19:1602–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Humayun MS, Dorn JD, da Cruz L, et al. . Interim results from the international trial of Second Sight's visual prosthesis. Ophthalmology 2012;119:779–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ho AC, Humayun MS, Dorn JD, et al. . Long-term results from an epiretinal prosthesis to restore sight to the blind. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1547–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stingl K, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Besch D, et al. . Artificial vision with wirelessly powered subretinal electronic implant alpha-IMS. Proc Biol Sci 2013;280:20130077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bi A, Cui J, Ma YP, et al. . Ectopic expression of a microbial-type rhodopsin restores visual responses in mice with photoreceptor degeneration. Neuron 2006;50:23–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lagali PS, Balya D, Awatramani GB, et al. . Light-activated channels targeted to ON bipolar cells restore visual function in retinal degeneration. Nat Neurosci 2008;11:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Busskamp V, Duebel J, Balya D, et al. . Genetic reactivation of cone photoreceptors restores visual responses in retinitis pigmentosa. Science 2010;329:413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mace E, Caplette R, Marre O, et al. . Targeting channelrhodopsin-2 to ON-bipolar cells with vitreally administered AAV restores ON and OFF visual responses in blind mice. Mol Ther 2015;23:7–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lin B, Koizumi A, Tanaka N, et al. . Restoration of visual function in retinal degeneration mice by ectopic expression of melanopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:16009–16014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cehajic-Kapetanovic J, Eleftheriou C, Allen AE, et al. . Restoration of vision with ectopic expression of human rod opsin. Curr Biol 2015;25:2111–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gaub BM, Berry MH, Holt AE, et al. . Optogenetic vision restoration using rhodopsin for enhanced sensitivity. Mol Ther 2015;23:1562–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Wyk M, Pielecka-Fortuna J, Lowel S, et al. . Restoring the ON switch in blind retinas: Opto-mGluR6, a next-generation, cell-tailored optogenetic tool. PLoS Biol 2015;13:e1002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jacobson SG, Sumaroka A, Luo X, et al. . Retinal optogenetic therapies: clinical criteria for candidacy. Clin Genet 2013;84:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Evans MJ, and Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 1981;292:154–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Takahashi K, and Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006;126:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. . Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007;131:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alexander P, Thomson HA, Luff AJ, et al. . Retinal pigment epithelium transplantation: concepts, challenges, and future prospects. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:992–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nazari H, Zhang L, Zhu D, et al. . Stem cell based therapies for age-related macular degeneration: the promises and the challenges. Prog Retin Eye Res 2015;48:1–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jayakody SA, Gonzalez-Cordero A, Ali RR, et al. . Cellular strategies for retinal repair by photoreceptor replacement. Prog Retin Eye Res 2015;46:31–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seiler MJ, and Aramant RB. Cell replacement and visual restoration by retinal sheet transplants. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012;31:661–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Leach LL, and Clegg DO. Concise review: Making stem cells retinal: methods for deriving retinal pigment epithelium and implications for patients with ocular disease. Stem Cells 2015;33:2363–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schwartz SD, Hubschman JP, Heilwell G, et al. . Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report. Lancet 2012;379:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schwartz SD, Anglade E, Lanza R, et al. . Stem cells in age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt's macular dystrophy—authors' reply. Lancet 2015;386:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trounson A, and McDonald C. Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell 2015;17:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stanzel BV, Liu Z, Somboonthanakij S, et al. . Human RPE stem cells grown into polarized RPE monolayers on a polyester matrix are maintained after grafting into rabbit subretinal space. Stem Cell Reports 2014;2:64–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Caras IW, Littman N, and Abo A. Proceedings: debilitating eye diseases. Stem Cells Transl Med 2014;3:1393–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Diniz B, Thomas P, Thomas B, et al. . Subretinal implantation of retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells: improved survival when implanted as a monolayer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:5087–5096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.RIKEN. Pilot clinical study into iPS cell therapy for eye disease starts in Japan [2013 July 30; accessed 2016January21]. Available from: http://www.riken.jp/en/pr/press/2013/20130730_1; Cyranoski D. Japanese woman is first recipient of next-generation stem cells [2014. September 12; accessed 216 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.nature.com/news/japanese-woman-is-first-recipient-of-nextgeneration-stem-cells-1.15915

- 112.Borooah S, Phillips MJ, Bilican B, et al. . Using human induced pluripotent stem cells to treat retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2013;37:163–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen FK, McLenachan S, Edel M, et al. . iPS cells for modelling and treatment of retinal diseases. J Clin Med 2014;3:1511–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, et al. . Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature 2006;444:203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Barber AC, Hippert C, Duran Y, et al. . Repair of the degenerate retina by photoreceptor transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:354–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pearson RA, Barber AC, Rizzi M, et al. . Restoration of vision after transplantation of photoreceptors. Nature 2012;485:99–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gonzalez-Cordero A, West EL, Pearson RA, et al. . Photoreceptor precursors derived from three-dimensional embryonic stem cell cultures integrate and mature within adult degenerate retina. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:741–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Decembrini S, Koch U, Radtke F, et al. . Derivation of traceable and transplantable photoreceptors from mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2014;2:853–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lamba DA, Gust J, and Reh TA. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived photoreceptors restores some visual function in Crx-deficient mice. Cell Stem Cell 2009;4:73–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Eberle D, Schubert S, Postel K, et al. . Increased integration of transplanted CD73-positive photoreceptor precursors into adult mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:6462–6471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lakowski J, Han YT, Pearson RA, et al. . Effective transplantation of photoreceptor precursor cells selected via cell surface antigen expression. Stem Cells 2011;29:1391–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reichman S, Terray A, Slembrouck A, et al. . From confluent human iPS cells to self-forming neural retina and retinal pigmented epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:8518–8523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lakowski J, Gonzalez-Cordero A, West EL, et al. . Transplantation of photoreceptor precursors isolated via a cell surface biomarker panel from embryonic stem cell-derived self-forming retina. Stem Cells 2015;33:2469–2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Assawachananont J, Mandai M, Okamoto S, et al. . Transplantation of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived 3D retinal sheets into retinal degenerative mice. Stem Cell Reports 2014;2:662–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nakano T, Ando S, Takata N, et al. . Self-formation of optic cups and storable stratified neural retina from human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 2012;10:771–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhong X, Gutierrez C, Xue T, et al. . Generation of three-dimensional retinal tissue with functional photoreceptors from human iPSCs. Nat Commun 2014;5:4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bull ND, and Martin KR. Concise review: toward stem cell-based therapies for retinal neurodegenerative diseases. Stem Cells 2011;29:1170–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.McGill TJ, Cottam B, Lu B, et al. . Transplantation of human central nervous system stem cells—neuroprotection in retinal degeneration. Eur J Neurosci 2012;35:468–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]