Abstract

Dysregulated metabolism is an emerging hallmark of cancer and there is abundant interest in developing therapies to selectively target these aberrant metabolic phenotypes. Sitting at the decision point between mitochondrial carbohydrate oxidation and aerobic glycolysis (i.e., the “Warburg Effect”), the synthesis and consumption of pyruvate is tightly controlled and is often differentially regulated in cancer cells. This review examines recent efforts toward understanding and targeting mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism, and addresses some of the successes, pitfalls and significant challenges of metabolic therapy to date.

Keywords: Cancer, Metabolism, Pyruvate, Metabolic Flexibility, Metabolic Heterogeneity, Stem Cells

The Dynamic and Flexible Metabolic Network

Many of us can relate to the experience of a metabolic enzyme popping up in a dataset and then having to scramble to find a lab that has the metabolic map taped to the wall. Dr. Donald Nicholson, the originator of most of these maps, passed away in 2012 at the age of 96 [1]. For decades, Dr. Nicholson’s maps have provided the framework for our conception of metabolism, and this was generally to our great benefit. In one respect, however, this depiction of metabolism has perhaps contributed to a common misconception regarding the true nature of cellular metabolism. Those printed words and arrows of fixed dimension and orientation belie the dynamism and complexity that characterizes the metabolic network of a living cell.

To a greater or lesser extent, every cell on earth does metabolism differently from every other cell. Even a single given cell does not behave in the same manner from one minute to the next. Most cells constantly monitor their available nutrients, their own needs and other aspects of their environment and make (sometimes dramatic) alterations to the wiring and flux of their metabolic network. When the combination of internal, neuronal, environmental, and hormonal signals cause a cell to change its fate or behavior (e.g., to grow or differentiate or divide or change its gene expression program), this usually involves an adjustment to optimize the metabolism of the cell to this new behavior.

This dynamic character of the cellular metabolic network is commonly known as ‘metabolic flexibility’ and we posit that this metabolic flexibility is a critically important, but often unappreciated, feature of cellular physiology. In the case of cancer, however, adaptations that optimize the oncogenic process may ultimately limit the metabolic flexibility of some cancer cells and thereby increase susceptibility to metabolism-targeted therapies. While this hypothesis is still being tested, the promise of the metabolic approach to cancer therapy is predicated on this hypothesis being true, at least in a subset of cancers under a subset of conditions. Great challenges to this approach remain, however, including the flexibility that tumors retain, both in a cell autonomous manner and due to metabolic heterogeneity across the population of tumor cells. This review discusses metabolic flexibility, with a focus on mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism, the successes, failures, opportunities and pitfalls of modulating pyruvate metabolism in cancer.

Metabolic Flexibility in Normal and Disease Physiology

All living organisms rely on metabolic flexibility for survival in an evolving environment. Persistent adaptations are common during development as stem cells give rise to the differentiated cells and tissues present in the adult body, and continue to adapt during remodeling, regeneration, and aging [2]. In general, stem cell differentiation is associated with a change in the carbohydrate metabolic program, with pyruvate being the site of bifurcation. Most differentiation paradigms are characterized by a transition from glycolytic metabolism to mitochondrial oxidative metabolism [3,4] (see Figure 1 and discussed in more detail below).

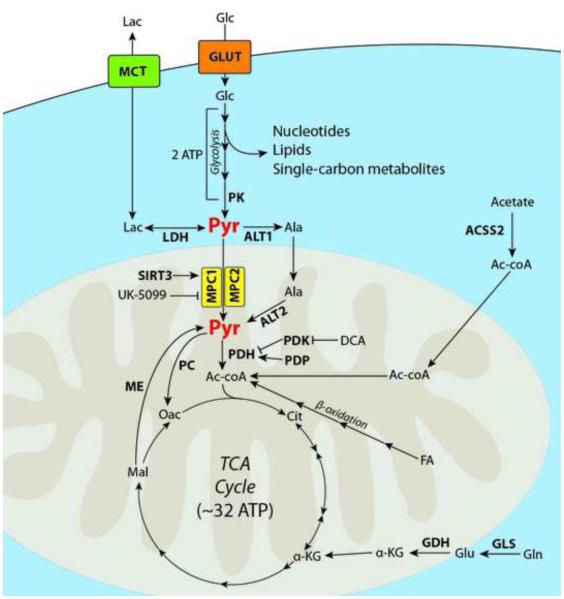

Figure 1. The centrality of pyruvate metabolism.

Glucose (Glc) enters the cell via the GLUT family of transporters. It is then catabolized by several enzymes during the process of glycolysis, yielding two molecules of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Intermediates of glycolysis contribute to nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis, as well as single-carbon donors. The final enzyme of glycolysis, pyruvate kinase (PK), yields 2 molecules of pyruvate (Pyr). Pyruvate can either be utilized in other biosynthetic reactions (such as an amine receptor for alanine transaminase (ALT)), reduced to lactate (Lac) by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and excreted from the cell via the monocarboxylate transporters (MCT), or transported into the mitochondrial matrix via the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC). The MPC can be activated by deacetylation of K45 and K46 by Sirtuin 3, and inhibited by the small molecule UK-5099. Once in the mitochondria, pyruvate can be oxidized via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) to form acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-coA). The PDH kinases (PDK) phosphorylate PDH to make it inactive. This phosphorylation can be reversed by the PDH phosphatases (PDP), or prevented by the PDK inhibitor dichloroacetate (DCA). Acetyl-CoA is then condensed with Oxaloacetate (Oac) to form citrate (Cit) and begin the first turn of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to yield an additional ~30-34 molecules of ATP. In some conditions, acetyl-coA can be generated from scavenged acetate via acetyl-coa synthetase 2 (ACSS2), or via β-oxidation of fatty acids (FA). Some cancers cells in vitro heavily rely on glutamine (Gln) to replenish TCA cycle intermediates by converting it to glutamate (Glu) via glutaminase (GLS), and then to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) via glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). In other situations, pyruvate may additionally be consumed by pyruvate carboxylase (PC) to form oxaloacetate and bypass the TCA cycle. Similarly, pyruvate can be replenished in the mitochondria from malate (Mal) by malic enzyme (ME). Transporters are illustrated in rounded boxes, proteins and relevant enzymes are shown in bold, major biochemical pathways are shown in italic, metabolites and small molecules are shown in regular type, with the exception of pyruvate.

Acute adaptations are also common and critical. During vigorous exercise, when the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) demand outstrips the availability of oxygen, skeletal muscle shifts from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to glycolytic ATP generation. Rather than entering the mitochondria, pyruvate is converted to lactate and excreted from the cell. This acute adaptation is required to enable the continued contractile function of muscle during extended exercise, and is familiar to all with sore muscles or a “Charlie horse”. Christian Metallo and colleagues recently elegantly demonstrated this adaptability at the level of isolated individual cells. Using C2C12 myoblasts, they studied the impact of blocking the mitochondrial oxidation of three of the principal oxidative fuels of these cells: pyruvate (from carbohydrates), glutamine and fatty acids [5] (see Figure 1). Blocking any two of these pathways had negligible effects on oxygen consumption associated with ATP production. It was only when all three were simultaneously inhibited that a significant decrease in oxygen consumption was observed, and that was only a 30% decrement. Shuttling pyruvate-derived alanine into the mitochondria, which was recently shown in the liver [6,7], might bypass the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC, see Glossary) and thereby contribute to the observed resiliency of oxygen consumption.

While metabolic flexibility is a nearly universal property of normal healthy cells, it appears to be compromised in several disease settings. One example is the failing adult heart [8]. The fetal heart primarily produces ATP through glycolytic metabolism of carbohydrate substrates [9]. Over the course of development, the heart transitions such that fatty acid β-oxidation largely fuels the adult heart, but the heart retains the flexibility to temporarily switch to a glycolytic phenotype depending on nutrient availability and energetic demand [10]. It is becoming clear that the development of heart failure is accompanied by a reversion back to the fetal glycolytic program and a loss of metabolic flexibility [11-14], which may be potentiated by decreased expression of the MPC [15,16]. This metabolic regime was first described over 100 years ago, when patients with various heart maladies temporarily improved after administration of cane sugar [17].

Metabolic Inflexibility in Cancer

During the process of oncogenesis, cells destined to populate a tumor acquire a series of adaptive phenotypes that are beneficial or even necessary for survival and/or proliferation, as evidenced by their strong positive selection [18]. Some of these phenotypes, such as the establishment of a specific transcriptional program, are readily reversible and probably evolve or revert over time as the demands and environment of the cell change. Other adaptations are irreversible, including genomic mutation, deletion or amplification of tumor suppressor genes or proto-oncogenes. For example, every progeny of a cell with a homozygous mutation destroying succinate dehydrogenase will forever be succinate dehydrogenase deficient [19-21], even if that status becomes detrimental to the cell in some future scenario. While there are some cases wherein metabolic adaptations in cancer have been irreversibly established by genetic mutation, deletion or amplification of metabolic enzymes, the majority of cancer metabolic adaptations seem to belong to a third class of adaptive phenotypes. They are theoretically reversible, but that reversion comes at a significant cost in oncogenic potential. The efficacy of the majority of cancer therapies relies on the exploitation of these latter two classes of adaptations (irreversible and costly reversible), and we will discuss below the promise and challenges of targeting the latter metabolic phenotypes.

The prototypical metabolic profile of cancer was first described by Otto Warburg in 1927[22] and involves cancer cells oxidizing a lower fraction of their glucose completely to carbon dioxide than normal tissue in spite of adequate oxygenation. The consequence of this so-called Warburg Effect is a compensatory increase in glucose consumption and lactate production. Under this paradigm the majority of glucose taken up by the cancer cell undergoes glycolysis to form two molecules of pyruvate (Figure 1). At this step, however, pyruvate is diverted from the mitochondrial oxidative pathway, converted to lactate through lactate dehydrogenase (LDH-A), and that lactate is exported from the cell, typically via the monocarboxylate transporter MCT-4 [23,24].

As described, this energetically inefficient metabolic profile seems counterintuitive. In fact, much of the glucose-derived carbon is diverted into biosynthetic pathways, which is likely a major reason that cancer cells bias against complete pyruvate oxidation as it results in losing carbon as carbon dioxide. It appears that ATP production is simply not rate limiting for cancer cell proliferation and the cell places a greater emphasis on the synthesis and acquisition of the building blocks that are necessary to construct a new cell. To this end, the Warburg Effect is accompanied by several additional adaptations that optimize for biosynthesis. While the frequency and extent of these individual effects is less well established than for aerobic glycolysis, this principle of enhancing biosynthetic metabolism through limiting pyruvate oxidation is likely to apply to most cancers [25,26].

The Centrality and Multi-Layered Regulation of Pyruvate Metabolism

One could make a compelling argument that pyruvate is the nexus of the entire cellular metabolic network (Figure 1). It occupies the junction between cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolism, and of specific relevance to this review, the pattern of pyruvate generation and disposition is the cardinal distinction between normal metabolism and “cancer metabolism”. Essentially every protein that manages pyruvate synthesis and consumption has been described as somehow differentially regulated in cancer cells relative to normal cells. These adaptations, hypothesized to be costly to reverse for cancer cells, are the subject of intense exploration for therapeutic exploitation.

Pyruvate is synthesized as the last step of glycolysis by pyruvate kinase (PK), which exists as either the M1 or M2 isoform in most cell types. The regulation of expression of these isoforms is complex [27]; however, it appears that in many cancers the M2 isoform is 4-6 times more prevalent than M1 [28], whereas normal tissues with high ATP demand tend to predominantly express the M1 isoform. The M2 isoform is sensitive to inhibition by phospho-tyrosine motifs [29,30] and other inputs that are stimulated by growth factor signaling [31]. As a result, cells with an elevated PK-M2/PK-M1 ratio have the potential to slow the production of pyruvate in response to proliferation signals. This phenomenon presumably enables a preferential utilization of glycolytic intermediates for the biosynthesis of building blocks, including nucleotides, amino acids, and one-carbon donors [1,32,33].

The cytosolic pyruvate synthesized by pyruvate kinase lies at a site of bifurcation. It can either be transported into mitochondria (see below) or, in cells expressing the non-oxidative glycolytic (Warburg effect) program, it remains in the cytosol to be converted to lactate and exported from the cell, or for use in other biosynthetic reactions such as aspartate synthesis [2,34,35]. Pyruvate is converted to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase (typically the LDH-A isoform), which is frequently overexpressed and serves as a prognostic marker for poor survival in many cancers [3,4,36]. Inhibition of LDH-A increases oxygen consumption, presumably due to an increase in mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation [5,37]. As would be expected if the Warburg metabolic profile is positively selected in cancer cells, numerous studies [6,7,38] have shown that colony formation [8,39], proliferation [9,39-41], metastasis [10,40], and survival [11-14,37] is dependent upon LDH-A activity.

Lactate can then be exported from the cell by the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family of integral membrane proteins. MCT-1 and MCT-4 have both been implicated in lactate export, although recent data suggest that MCT-4 plays the predominant role in many cancers. Much like LDH-A, several studies have demonstrated that MCT-4 expression, which is elevated in many cancers, is required for the full expression of the cancer phenotype and is associated with poor clinical outcomes [15,16,42-46].

In oxidative cells, pyruvate is transported into mitochondria by the MPC, which is composed of the MPC1 and MPC2 subunits. The activity of this transporter was described decades ago, but was only recently molecularly identified [17,47,48]. The discovery of the encoding genes enabled the observation that most cancers exhibit decreased expression of MPC1 and MPC2, with MPC1 being the most strongly and consistently affected. The decreased expression and activity of the MPC seems to be an essential feature of the metabolic program, at least in colon cancer cells, as forced re-expression of MPC1 and MPC2 impaired colony formation in vitro and tumor xenograft growth in mice [18,49]. Recently, MPC activity was shown to be modulated by the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirtuin-3, with MPC1 acetylation at K45 and K46 reducing mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation [19-21,50].

The next step in the carbohydrate oxidation pathway is the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-coA in the mitochondrial matrix by the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) enzyme complex. Unlike the other proteins and complexes described in this section, there is little evidence of cancer-associated changes in the expression of the genes encoding PDH. There is also little evidence of the expression of distinct isoforms or splice variants of PDH complex genes in cancer cells. There is abundant evidence, however, of profound post-translational regulation of PDH in cancer by inhibitory phosphorylation. PDH kinase 1 (PDK1), which is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, phosphorylates and inactivates PDH and PDK1 expression has been strongly implicated in oncogenesis [22,51-53]. This phosphorylation can be reversed, and PDH activity restored, by PDP2 and other PDH phosphatases (PDP) [23,24,51].

Acetyl-coA (produced by PDH) is then condensed with oxaloacetate to form citrate by the enzyme citrate synthase, which initiates the first turn of the TCA cycle. In some situations, cancer cells produce acetyl-coA from scavenged acetate via acetyl-coA synthetase 2 (ACSS2), in order to maintain proliferation during metabolic stress [25,26,54-56].

The extent and diversity of regulatory modalities employed to limit pyruvate oxidation in cancer cells suggests its importance. As briefly described for each protein, the data suggest that while these metabolic adaptations that divert pyruvate metabolism are enacted and reversed in a facile manner in normal cells, such as in skeletal muscle during exercise, they have become difficult to reverse in cancer cells. One might hope that a cancer trapped in this “costly reversible” metabolic state might be selectively killed with the appropriate combination of metabolism-modulating agents.

Catching cancer in the metabolic crab pot: attempts, failures and hope for the future

The mainstay of cancer therapy has been, and will probably continue to be, the exploitation of the irreversible or costly reversible adaptations made during the oncogenic process, which act like a ‘crab pot’ from which the cancer cannot easily escape. The cancer cell, in pursuit of energetic, biosynthetic or survival advantage, may have trapped itself in a ‘metabolic crab pot’. If that is true, then the remaining question is whether we can capitalize on that entrapment to selectively kill cancer cells, while allowing the escape of normal cells that have retained their metabolic flexibility.

Perhaps the best-studied example of a candidate cancer therapy that acts through directly modulating metabolism is the drug dichloroacetate (DCA). An abundant byproduct of industrial organic halogenation reactions, its pharmacologic utility was investigated as early as the mid-20th century. By the 1970s, DCA showed to be highly effective as an anti-diabetic and lipid-lowering agent [27,57]. Shortly thereafter, one mechanism of DCA (although it likely has other effects) was discovered as it was shown to stimulate PDH activity by inhibiting the PDH kinases, thereby preventing inhibitory PDH phosphorylation [28,58]. It was not until 2007, with renewed interest in cancer metabolism, that Bonnet, et al hypothesized that DCA could potentially act to reverse the Warburg Effect, promote mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation, and decrease tumor proliferation [29,30,59]. Since then, for a curious (and unfortunately erroneous) range of reasons, DCA has developed something of a cult following, with several reports of patients self-administering the drug in hopes that it may reduce tumor burden [31,60].

Over 150 manuscripts have been published on DCA in recent years and 19 clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate its effectiveness in treating various cancers and metabolic diseases. In some cases, DCA has shown positive signs of efficacy and great promise as an adjunct chemotherapy. For example, in combination with certain platinum-based chemotherapies, DCA has been shown to enhance cytotoxicity in several solid tumor derived cell lines [61,62] and to reverse cisplatin resistance [63]. It is possible that DCA exacerbates the effects of these DNA cross-linking agents by reducing the biosynthesis of nucleotides necessary for DNA repair [64] or through other as-yet-undetermined metabolic effects.

While some studies have shown promise for DCA as a cancer treatment, several others suggest that its therapeutic potential may be limited. In the colorectal cancer cell line HCT116, DCA has been shown to affect cell proliferation without affecting survival or inducing apoptosis [65]. In other cancer cell lines, the effects were more varied [66]. In fact, one study showed that DCA reduced apoptosis in hypoxic tumors, while enhancing proliferation and xenograft formation [67]. Similar results were found in neuroblastoma xenografts, where DCA promoted their progression [68]. Why has DCA shown anti-cancer efficacy in some situations and not in others? One clear possibility is that pyruvate metabolism is regulated at other points in the pathway, as described above. For example, in a situation where MPC1 is deleted from the genome, which is a common occurrence in cancer [49,69], and pyruvate entry into the mitochondria is limited, the activation state of the PDH complex might be of less consequence and the DCA has little effect. Overexpression of LDHA/MCT-4 to siphon off cytosolic pyruvate for lactate export or the inhibition of pyruvate kinase might similarly mitigate the effects of PDH activation.

It is important to appreciate the complexity and redundancy of the regulation of mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation as we try to exploit the potential inflexibility of the cancer metabolic phenotype. Many new drug candidates are in development to target these metabolic “crab pots” and one hopes that they will be useful therapies alone and/or in combination. For example, many colon cancers reduce or eliminate mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation via down-regulation or genomic deletion of the MPC1 gene. A recent study [70] demonstrated that by reducing pyruvate flux into the mitochondria, the cell becomes more reliant on the mitochondrial catabolism of glutamate. By inhibiting glutaminase or glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), in concert with the MPC, the mitochondria became depleted of available carbon sources, which decreased cell growth and increased cell death. This finding directly lends itself to therapeutic application, provided that MPC status can be determined in a tumor biopsy. In tumors with low or absent MPC expression, one might expect increased susceptibility to glutaminase inhibition. By contrast, normal or differentiated cells, which retain their metabolic flexibility, would be better able to compensate for the loss of this source of glutamate and alpha-ketoglutarate through pyruvate fueling of the TCA cycle.

As we continue to build on the previous decades of metabolic biochemistry, the development of small molecules that target additional metabolic nodes will supply new tools to target the metabolic inflexibilities of tumors. However, it is essential that we understand the integration of these biosynthetic pathways, the nature of these irreversible (or costly reversible) adaptations and the points of inflexibility that they cause. When we are capable of ascertaining this for a given tumor in a given patient, then a combination of agents that target different facets of the tumor’s metabolism might be used to precisely apply pressure to these specific liabilities. If this “pressure” is supplied sufficiently precisely, it may spare non-neoplastic tissues due to their retained metabolic flexibility. While this field is rapidly expanding and there is great hope that it will change the course of cancer treatment, many significant hurdles remain.

Why has metabolic therapy not cured cancer?

It is well established that the cells within tumors are genetically, epigenetically and metabolically heterogeneous, as has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [71,72]. Just as tumor heterogeneity poses challenges to conventional chemotherapies, tumor heterogeneity is likely to be a major hurdle for metabolic therapies. In the context of conventional chemotherapy, some cells rapidly proliferate and therefore their replication machinery can be effectively targeted, however other tumor cells quiesce and remain resistant to conventional chemotherapy. This cell population has been shown in some cases to provide the cells responsible for proliferation after remission [73]. A similar challenge might be expected for metabolic therapies, in that some cells within a tumor might not exhibit the same dependence and sensitivity that is being exploited to target the bulk of the tumor.

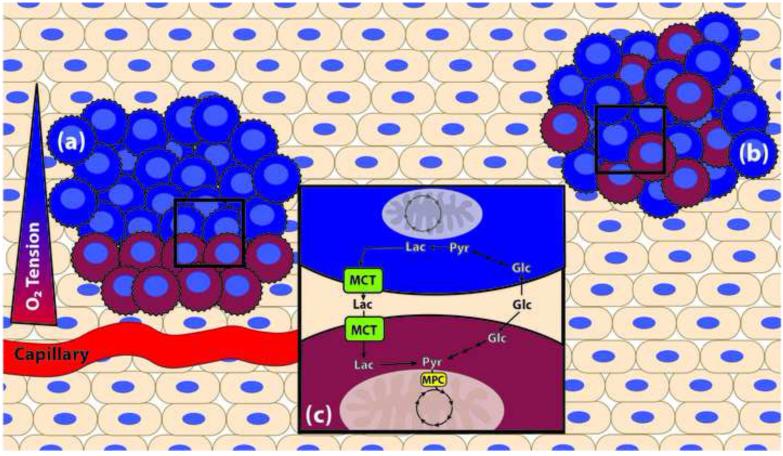

One source of tumor heterogeneity is the varying physical proximity of different parts of the tumor to the vasculature (Figure 2A). Proximity to vasculature provides pro-growth signaling to the tumor, as well as providing oxygen to fuel oxidative metabolism. Conversely, those regions of the tumor distant from vessels where oxygen is severely limited would be forced to adapt to a different metabolic regime within the hypoxic environment (Figure 2A). Transcriptional control of metabolic adaptations to hypoxia are regulated by hypoxia inducible factors (HIF), which are discussed further in Box 1.

Figure 2. Metabolic tumor heterogeneity.

Within a given tumor, adjacent cancer cells may operate under different metabolic regimes, lending to whole-tumor flexibility even if individual cancer cells (jagged edges) have limited metabolic flexibility. In the figure, two metabolic regimes are represented: one performing more mitochondrial oxidation (red), and one performing more aerobic glycolysis (blue). The architecture of metabolically heterogeneous tumors may be stratified by proximity of cancer cells to vasculature, depending on nutrient and oxygen availability (a). Tumor heterogeneity may also be more interspersed, where stochastic mutations during the oncogenic process select for individual cells that may complement the metabolic needs of an adjacent cell or cancer cell (b). In this example (c), the blue cells perform glycolysis to convert glucose (Glc) to pyruvate (Pyr) and then to lactate (Lac) which is exported from the cell via the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT). The adjacent red cells can take up that lactate (via another MCT), and convert it to pyruvate for use in mitochondrial oxidation. It is likely that tumors are comprised of many more metabolic phenotypes than the simplistic two-part system illustrated here, based on the numerous mutations and aberrations to their metabolic machinery that are mutually selected for during oncogenesis.

Box 1. The role of hypoxia and HIF.

Transcriptional regulation of the metabolic adaptation to hypoxia is largely driven by heterodimeric transcriptions factors, collectively known as the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIF). Under conditions of normoxia, HIF activity is very low, as the alpha subunits are rapidly degraded by the process of oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylation, binding of von Hippel-Lindau factor (VHL), E3 ubiquitin ligation and proteasomal degradation [88,89]. In hypoxic conditions, however, HIF is stabilized and modulates expression of a number of metabolic genes.

Some of the early discovered metabolic adaptations tied HIF to increased glucose uptake via the GLUT transporters [90,91], and increased rate of glycolysis by upregulating expression of many glycolytic enzymes [92-94], increased lactate production via LDH-A [94] and lactate excretion by MCT4 [95,96]. In sum, these studies show that HIF may be a master regulator of glycolysis under hypoxic conditions. However, in 2006 two studies showed that not only does HIF promote glycolysis, but actively represses mitochondrial oxidation by increasing expression of PDK1 [97,98], thus inhibiting PDH and preventing pyruvate from entering the TCA cycle. Many cancer-associated mutations have been shown to increase HIF expression and/or stability [88], irrespective of cellular oxygen tension. These important discoveries revived study of the Warburg Effect, and provided rationale for the development of HIF inhibitors that could theoretically reverse the Warburg Effect in one fell swoop.

The study, development, and clinical application of HIF regulation and inhibition is complex and ever-evolving, and we refer the reader to recent reviews for a more in-depth discussion of this topic [99-103].

Apart from spatially organized heterogeneity, it has recently been shown in the case of several solid tumors types that even adjacent cells adopt distinct metabolic programs (Figure 2B)[74]. One cell can perform aerobic glycolysis, which will generate lactate that is exported by one of the MCT transporters; an adjacent cell can then take up that lactate and, by the action of lactate dehydrogenase, convert the lactate to pyruvate for use in mitochondrial oxidation (Figure 2C) [75,76]. This phenomenon has been coined the “reverse Warburg effect” and has also been described to occur between the tumor and tumor stroma [77,78].

The combination of both glycolytic and oxidative cells within a tumor poses significant therapeutic challenges, even if the cells themselves are metabolically inflexible. For example, treatment with an LDH or MCT inhibitor may successfully target the glycolytic population of cells within a tumor by depleting NAD+ and/or decreasing the intracellular pH. However, those cells with an oxidative metabolic regime would be largely unaffected by such a treatment strategy as they may not employ the same isoforms of LDH or MCT. This would pose a particularly unfortunate therapeutic problem, as it has been shown that oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial carbon oxidation are essential for metastasis [79] and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [80] in several solid tumor types. The outcome of the therapy, while potentially debulking the primary lesion, could result in an increasingly malignant and nefarious population of cancer cells. In effect, the metabolic heterogeneity within a tumor could provide whole-tumor “metabolic flexibility”.

Another challenge inherent to targeting cancer cell metabolism is that normal stem cells frequently have a very similar metabolic phenotype [81]. Stem cells, perhaps due to their need to avoid oxidative damage or to thrive in a hypoxic niche [82,83], often adopt a glycolytic metabolic phenotype. In this situation, the cytotoxic effects of forcing a glycolytic tumor to engage mitochondrial oxidative metabolism could also damage the stem cell compartment [84], which would result in similar toxicities to conventional chemotherapeutics. To truly achieve stem cell-sparing metabolic therapies, we must further understand the differences between the metabolic phenotypes of cancer cells and stem cells, while realizing that each tumor and each stem cell niche contains a heterogeneous cell population.

Beyond just having similar physiology, the transcriptional and signaling drivers of the metabolic profiles of cancer and stem cells seem to be similar also. The pre-eminent example of this role duality is the oncogenic transcription factor Myc. On the one hand, Myc amplification and activation is found in numerous solid and lymphoid tumors, and its constitutive activation results in a dramatic and deranged metabolic program favoring a glycolytic phenotype by both activating and repressing numerous metabolic genes involved in glycolysis and glutaminolysis [85]. On the other hand, it has been shown that Myc is essential for maintaining stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency [86,87]. In both cases, key outputs for Myc include those that promote a glycolytic phenotype.

With such regulatory mechanisms common to both stem cells and cancer, we clearly need a new and improved level of understanding of both systems to enable us to kill one cell while sparing the other. One specific reason for hope is that the adaptations of cancer cells might have come at the cost of losing metabolic flexibility that is otherwise retained within the stem cell population. Another reason for optimism is that our growing understanding will teach us how to design combination therapies that increase the metabolic therapeutic window enough that cancer cells are specifically targeted.

Concluding Remarks

There is much excitement and renewed fervor in the study of metabolism; particularly in its application to cancer. A new appreciation of its complexity and dynamism provides a spatial and temporal elaboration on the rigid maps of Dr. Nicholson. The key for us moving forward (see Outstanding Questions) is determining where the flexibility exists, where it is lost, and how to best exploit those inflexibilities that characterize some cancer cells. There are many substantial difficulties in targeting these metabolic inflexibilities in cancer, in particularly those surrounding pyruvate metabolism. That cancer and stem cells share metabolic phenotype and machinery is a particularly troublesome hurdle, as is the metabolic heterogeneity of tumors.

In spite of these challenges, there are great possibilities. To be successful, we must understand and evaluate each tumor on an individual basis, and balance targeting its inflexibilities with sparing sensitive normal cells. Recent discoveries are providing insight with which to understand why certain metabolic modulators are effective and others are not and why some cancers respond and others do not. Already we are seeing early successes of metabolic therapy in combination with conventional chemotherapy, such as with DCA and cisplatin. As the metabolic adaptations of cancers come more sharply into focus, so will our ability to target them, increasing our therapeutic precision and creating the potential for stem cell-sparing therapies. We have just begun a great odyssey, one that will inevitably be filled with great difficulty, but there is great promise that this path will lead us to the goal of more safe and effective therapies for cancer.

Outstanding Questions.

Through the lens of newly discovered metabolic enzymes and regulators, like the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier, can we determine why previous therapeutic metabolic modulators have been inefficient and can we make them more effective?

How can we identify scenarios where tumor metabolic flexibility is sufficiently limited to favor responsiveness to metabolic modulators alone or in combination with conventional chemotherapeutics?

Is it possible to better define tumor metabolic heterogeneity in order to target it in a way that eradicates metabolically symbiotic cancer cells?

Is the metabolic regime of stem cells sufficiently more flexible than cancer cells such that we can create stem cell sparing metabolic therapies that retain potent anti-cancer efficacy?

Trends.

The ability of cells to respond to different nutrient conditions and energetic demands is known as ‘metabolic flexibility’ and is an essential feature of normal cellular physiology.

Adaptations that occur during the process of cancer formation may limit the metabolic flexibility of some cancers.

Metabolic therapies designed to target cancers are predicated on the hypothesis that some cancers are less metabolically flexible than normal tissues, and this may be a means to selectively target cancer while sparing other tissues.

Pyruvate metabolism is a central, differentially regulated, nexus of carbon metabolism that both provides and limits flexibility in normal and cancer tissues.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Matt Vander Heiden and Dr. Ralph DeBerardinis for their critical appraisal of this review. Related work in the Rutter laboratory is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation, NIH R01 GM094232 (to J.R.), and NIH Hematology Training Grant 5T32 DK007115 (to K.A.O.).

Glossary

- Acetyl-coA synthetase isoform 2 (ACSS2)

a nucleocytosolic enzyme that converts acetate to acetyl-coA.

- Alanine transaminase (ALT)

an enzyme that transaminates pyruvate and glutamate to form alanine and α-ketoglutarate. Isoform 1 is in the cytosol, and isoform 2 localizes to mitochondria.

- β-oxidation

A four-step process within the mitochondria where fatty acids are oxidized to form acetyl-coA.

- Dichloroacetate (DCA)

an inhibitor of PDK.

- Glucose transporter (GLUT)

a family of proteins that transport glucose across the plasma membrane.

- Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH)

an enzyme that converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate.

- Glutaminase (GLS)

a metabolic enzyme that deamidates glutamine to form glutamate.

- Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)

a family of transcription factors responsible for the metabolic and cellular adaptation to hypoxia (Box 1).

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

a metabolic enzyme that converts lactate to pyruvate. Isoform A favors the forward reaction, whereas isoform B favors the reverse reaction.

- Malic enzyme (ME)

a metabolic enzyme that converts malate to pyruvate.

- Monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)

isoforms 4 and 1 of this enzyme are responsible for lactate excretion, and lactate uptake, respectively.

- Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC)

a heterodimeric complex required for mitochondrial pyruvate import, composed of proteins MPC1 and MPC2.

- Pyruvate carboxylase (PC)

A mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzed the carboxylation of pyruvate to form oxaloacetic acid.

- Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)

the mitochondrial enzyme complex that converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA.

- Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)

Isoforms 1-4 of this enzyme phosphorylate and inactivate PDH.

- Pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (PDP)

Isoforms 1 and 2 reverse the inhibitory phosphorylation of PDH by PDK.

- Pyruvate kinase (PK)

isoforms M1 or M2 of this enzyme perform the terminal step in glycolysis to yield pyruvate.

- Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3)

a mitochondrial deacetylase that activates MPC1.

- 2-cyano-3-(1-phenyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-2-propenoic acid (UK-5099)

an inhibitor of the MPC complex.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Azzi A. memory of Donald Nicholson. IUBMB Life. 2012;648:659–660. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen KF, et al. Effect of aging on muscle mitochondrial substrate utilization in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514844112. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1514844112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takubo K, et al. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu W-M, et al. Metabolic Regulation by the Mitochondrial Phosphatase PTPMT1 Is Required for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vacanti NM, et al. Regulation of Substrate Utilization by the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier. Molecular Cell. 2014;56:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray LR, et al. Hepatic Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 1 Is Required for Efficient Regulation of Gluconeogenesis and Whole-Body Glucose Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.027. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCommis KS, et al. Loss of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 2 in the Liver Leads to Defects in Gluconeogenesis and Compensation via Pyruvate-Alanine Cycling. Cell Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.028. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop SP, Altschuld RA. Increased glycolytic metabolism in cardiac hypertrophy and congestive failure. The American journal of physiology. 218:153–159. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breckenridge RA, et al. Hypoxic regulation of hand1 controls the fetal-neonatal switch in cardiac metabolism. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin GW, et al. Improved energy homeostasis of the heart in the metabolic state of exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H1490–H1501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masoud WGT, et al. Failing mouse hearts utilize energy inefficiently and benefit from improved coupling of glycolysis and glucose oxidation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;101:30–38. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melenovsky V, et al. Availability of energetic substrates and exercise performance in heart failure with or without diabetes. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012;14:754–763. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ussher JR, et al. Stimulation of glucose oxidation protects against acute myocardial infarction and reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012;94:359–369. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doenst T, et al. Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: implications beyond ATP production. Circulation Research. 2013;113:709–724. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Zamora A, et al. Defective Expression of the Mitochondrial-tRNA Modifying Enzyme GTPBP3 Triggers AMPK-Mediated Adaptive Responses Involving Complex I Assembly Factors, Uncoupling Protein 2, and the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Caggiano M, et al. Analysis of mitochondrial proteins in the surviving myocardium after ischemia identifies mitochondrial pyruvate carrier expression as possible mediator of tissue viability. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2015 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.051862. DOI: 10.1074/mcp.M115.051862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulston A. A Note on the Beneficial Effect of the Ingestion of Cane Sugar in Certain Forms of Heart Disease. BMJ. 1911;1:615–615. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2620.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bardella C, et al. SDH mutations in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1807:1432–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:4675–4682. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutter J, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase–Assembly, regulation and role in human disease. Mitochondrion. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warburg O, et al. THE METABOLISM OF TUMORS IN THE BODY. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927;8:519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halestrap AP, Wilson MC. The monocarboxylate transporter family--role and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:109–119. doi: 10.1002/iub.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halestrap AP. The monocarboxylate transporter family--Structure and functional characterization. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:1–9. doi: 10.1002/iub.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boroughs LK, deberardinis RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:351–359. doi: 10.1038/ncb3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeNicola GM, Cantley LC. Cancer's Fuel Choice: New Flavors for a Picky Eater. Molecular Cell. 2015;60:514–523. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, et al. The multifaceted regulation and functions of PKM2 in tumor progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1846:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai S, et al. Tissue-specific isoform switch and DNA hypomethylation of the pyruvate kinase PKM gene in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2013;5:8202–8210. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christofk HR, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christofk HR, et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bettaieb A, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B regulates pyruvate kinase M2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:17360–17371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anastasiou D, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 activators promote tetramer formation and suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:839–847. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunt SY, et al. Pyruvate kinase isoform expression alters nucleotide synthesis to impact cell proliferation. Molecular Cell. 2015;57:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birsoy K, et al. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell. 2015;162:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan LB, et al. Supporting Aspartate Biosynthesis Is an Essential Function of Respiration in Proliferating Cells. Cell. 2015;162:552–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao P, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase a in cancer: A promising target for diagnosis and therapy. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:904–910. doi: 10.1002/iub.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le A, et al. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress and inhibits tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:2037–2042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914433107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fantin VR, et al. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie H, et al. Targeting lactate dehydrogenase--a inhibits tumorigenesis and tumor progression in mouse models of lung cancer and impacts tumor-initiating cells. Cell Metab. 2014;19:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheng SL, et al. Knockdown of lactate dehydrogenase A suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. FEBS J. 2012;279:3898–3910. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase A negatively regulated by miRNAs promotes aerobic glycolysis and is increased in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu J, et al. Monocarboxylate Transporter 4 Facilitates Cell Proliferation and Migration and Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witkiewicz AK, et al. Using the “reverse Warburg effect” to identify high-risk breast cancer patients: stromal MCT4 predicts poor clinical outcome in triple-negative breast cancers. cc. 2012;11:1108–1117. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.6.19530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakayama Y. Prognostic significance of monocarboxylate transporter 4 expression in patients with colorectal cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2011 doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.361. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2011.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baek G, et al. MCT4 defines a glycolytic subtype of pancreatic cancer with poor prognosis and unique metabolic dependencies. Cell Rep. 2014;9:2233–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hao J, et al. Co-expression of CD147 (EMMPRIN), CD44v3-10, MDR1 and monocarboxylate transporters is associated with prostate cancer drug resistance and progression. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;103:1008–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herzig S, et al. Identification and Functional Expression of the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier. Science. 2012;337:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1218530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bricker DK, et al. A Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier Required for Pyruvate Uptake in Yeast, Drosophila, and Humans. Science. 2012;337:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1218099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schell JC, et al. A Role for the Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier as a Repressor of the Warburg Effect and Colon Cancer Cell Growth. Molecular Cell. 2014;56:400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang L, et al. Sirt3 binds to and deacetylates mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 to enhance its activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.036. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplon J, et al. A key role for mitochondrial gatekeeper pyruvate dehydrogenase in oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2013;498:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujiwara S, et al. PDK1 inhibition is a novel therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. British Journal of Cancer. 2013;108:170–178. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hitosugi T, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 is important for cancer metabolism. Molecular Cell. 2011;44:864–877. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Comerford SA, et al. Acetate dependence of tumors. Cell. 2014;159:1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schug ZT, et al. Acetyl-CoA Synthetase 2 Promotes Acetate Utilization and Maintains Cancer Cell Growth under Metabolic Stress. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mashimo T, et al. Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell. 2014;159:1603–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stacpoole PW, Felts JM. Diisopropylammonium dichloroacetate (DIPA) and sodium dichloracetate (DCA): effect on glucose and fat metabolism in normal and diabetic tissue. Metab. Clin. Exp. 1970;19:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(70)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitehouse S, et al. Mechanism of activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by dichloroacetate and other halogenated carboxylic acids. Biochem. J. 1974;141:761–774. doi: 10.1042/bj1410761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonnet S, et al. A Mitochondria-K+ Channel Axis Is Suppressed in Cancer and Its Normalization Promotes Apoptosis and Inhibits Cancer Growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strum SB, et al. Case Report: Sodium dichloroacetate (DCA) inhibition of the “Warburg Effect” in a human cancer patient: complete response in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after disease progression with rituximab-CHOP. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012;45:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olszewski U, et al. vitro cytotoxicity of combinations of dichloroacetate with anticancer platinum compounds. Clin Pharmacol. 2010;2:177–183. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S11795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garon EB, et al. Dichloroacetate should be considered with platinum-based chemotherapy in hypoxic tumors rather than as a single agent in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014;140:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1583-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roh J-L, et al. Activation of mitochondrial oxidation by PDK2 inhibition reverses cisplatin resistance in head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.023. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Preter G, et al. Inhibition of the pentose phosphate pathway by dichloroacetate unravels a missing link between aerobic glycolysis and cancer cell proliferation. Oncotarget. 5 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delaney LM, et al. Dichloroacetate affects proliferation but not survival of human colorectal cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1046-4. DOI: 10.1007/s10495-014-1046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho N, Coomber BL. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase expression and metabolic changes following dichloroacetate exposure in anoxic human colorectal cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2015;331:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shahrzad S, et al. Sodium dichloroacetate (DCA) reduces apoptosis in colorectal tumor hypoxia. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feuerecker B, et al. DCA promotes progression of neuroblastoma tumors in nude mice. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:812–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tibiletti MG, et al. Physical map of the D6S149-D6S193 region on chromosome 6Q27 and its involvement in benign surface epithelial ovarian tumours. Oncogene. 1998;16:1639–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang C, et al. Glutamine Oxidation Maintains the TCA Cycle and Cell Survival during Impaired Mitochondrial Pyruvate Transport. Molecular Cell. 2014;56:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1805:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pribluda A, et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity: From Diversity Comes Resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:2916–2923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abelson S, et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity in the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenic Differentiation of Ovarian Cancer. Stem Cells. 2012;30:415–424. doi: 10.1002/stem.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Son SH, et al. Prognostic implication of intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:585. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sonveaux P, et al. Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3930–3942. doi: 10.1172/JCI36843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McGillen JB, et al. Glucose-lactate metabolic cooperation in cancer: insights from a spatial mathematical model and implications for targeted therapy. J. Theor. Biol. 2014;361:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Catabolic cancer-associated fibroblasts transfer energy and biomass to anabolic cancer cells, fueling tumor growth. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014;25:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fiaschi T, et al. Reciprocal metabolic reprogramming through lactate shuttle coordinately influences tumor-stroma interplay. Cancer Research. 2012;72:5130–5140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.LeBleu VS, et al. PGC-1α mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:992–1003. doi: 10.1038/ncb3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamabe A, et al. Role of pyruvate kinase M2 in transcriptional regulation leading to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407717111. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1407717111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ito K, Suda T. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:243–256. doi: 10.1038/nrm3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suda T, et al. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ushio-Fukai M, Rehman J. Redox and metabolic regulation of stem/progenitor cells and their niche. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;21:1587–1590. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodrigues AS, et al. Differentiate or Die: 3-Bromopyruvate and Pluripotency in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dang CV. MYC, metabolism, cell growth, and tumorigenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wilson A, et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Varlakhanova NV, et al. myc maintains embryonic stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. Differentiation. 2010;80:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maxwell PH, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen C, et al. Regulation of glut1 mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9519–9525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gleadle JM, Ratcliffe PJ. Induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, erythropoietin, vascular endothelial growth factor, and glucose transporter-1 by hypoxia: evidence against a regulatory role for Src kinase. Blood. 1997;89:503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mathupala SP, et al. Glucose catabolism in cancer cells: identification and characterization of a marked activation response of the type II hexokinase gene to hypoxic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43407–43412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iyer NV, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 1998;12:149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Semenza GL, et al. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ullah MS, et al. The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is up-regulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1alpha-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9030–9037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rosafio K, Pellerin L. Oxygen tension controls the expression of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 in cultured mouse cortical astrocytes via a hypoxia-inducible factor-1α-mediated transcriptional regulation. Glia. 2014;62:477–490. doi: 10.1002/glia.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim J-W, et al. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell. Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Papandreou I, et al. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Keith B, et al. HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Semenza GL. HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3664–3671. doi: 10.1172/JCI67230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Denko NC. Hypoxic regulation of metabolism offers new opportunities for anticancer therapy. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2014 doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.930345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Masoud GN, Li W. HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]