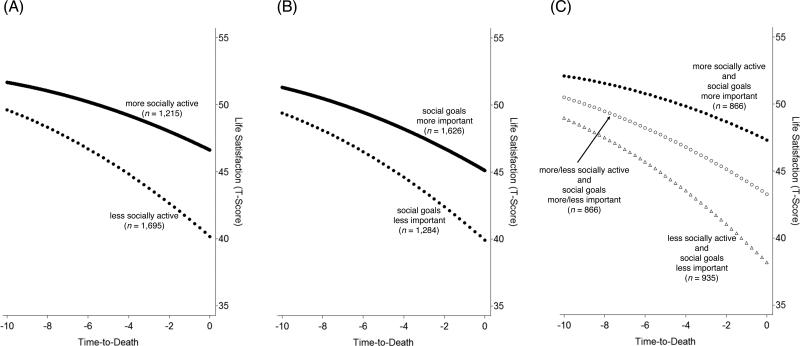

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration of associations between levels of social orientation and late-life trajectories of well-being, as obtained from single-phase models. Participants who reported living a more socially active life (left-hand Panel A) and those considering social goals relatively more important (middle Panel B) each also reported higher late-life well-being and experienced less severe terminal declines. Extrapolating back from the last available information about social orientation, group differences in well-being that existed 10 years before death were exacerbated in the year of death (for the social participation groups: from 2.05 T-score units to 6.45 T-score units or almost two thirds of a standard deviation; for the social goals groups: from 1.91 T-score units to 5.20 T-score units or about half a standard deviation). The right-hand Panel(C) illustrates the significant interaction according to which the effects of reduced social participation and lowered social goals were compounding each other: The combination of compromised social participation and lack of social goals was associated with particularly low well-being at one year prior to death. For illustration purposes, groups were defined using median splits. Scores for life satisfaction were standardized to a T metric (M = 50; SD = 10) using the 2002 SOEP sample as the reference frame (M = 6.90, SD = 1.81 on a 0–10 scale).