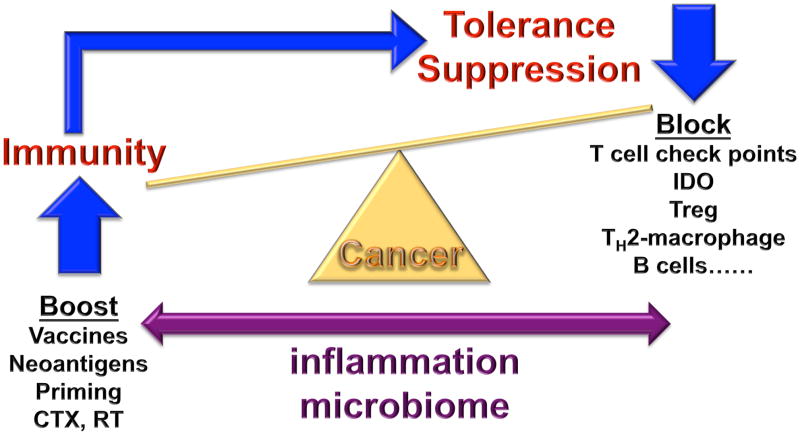

Figure 1. The makings of tumor immunity.

The communication between cancer and the immune system is a dynamic process, reminiscent of a balance. When immunity to cancer is ‘up’ and the suppressive processes are ‘down’, cancer is under control. However, a strong anti-tumor immune response will trigger largely physiological processes designed to dampen effector T cells to prevent tissue damage and maintain tissue homeostasis. Given that the immunity might have evolved mainly to maintain self, to establish coexistence with environment and to occasionally protect self from external threats, the suppression prevails. Multiple pathways of suppression are at play in tumor microenvironments including cells such as TH2-polarized macrophages, immature and suppressive monocytes, regulatory B cells and regulatory T cells, as well as molecules such as check points that control T cell differentiation (for example CTLA-4 and IDO) and effector function (such as PD-1). Pharmacological blockade of these inhibitory pathways can tip the balance towards anti-cancer effector T cells. The latter ones can be primed or boosted by antigen presenting cells (DCs) and/or by co-stimulatory signals (for example CD137 ligands). Recent studies demonstrate that thymus-independent neo-antigens generated in adult life by somatic mutation or post-translational regulation (for example phosphorylation) might be more immunogenic (or perhaps linked with less suppression) than shared tumor antigens. Neo-antigens can occur as random results of somatic mutation, as well as a by-product of anticancer treatments, e.g., chemotherapy (CTX) or radiation therapy (RT), or by targeting epigenetic control mechanisms or drugs intervening with DNA repair pathways. They can be presented to T cells in exogenous vaccines, as well as endogenously via DCs that captured dying neoplastic cells. When T cells specific to defined antigens kill neoplastic cells, such process can enable generation of responses to other antigens, so called epitope spreading. A critical factor in the balance between immunogenicity and suppression is inflammation (which in turn is impacted by the microbiome); indeed, the type of inflammation (tumor destructing TH1 or tumor promoting TH2 and TH17) should become a part of TNM grading, along with pathology, microbiome phenotype, and immune infiltrate assessment.