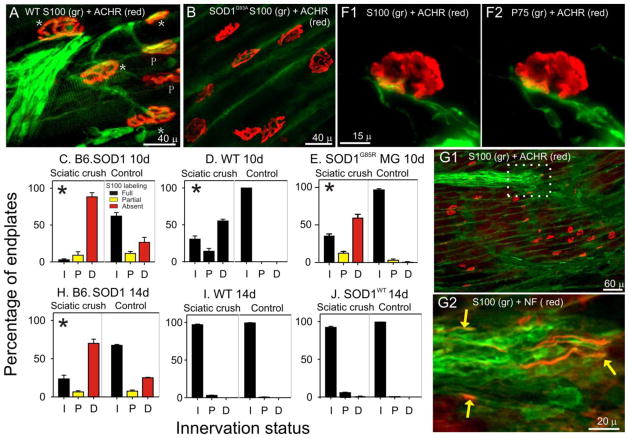

Figure 7.

NMJ S100 coverage and innervation 10 and 14d after sciatic crush denervation at P60. A. WT MG endplates 10 days after sciatic crush. Stars (*) indicate fully innervated endplates, P indicates partially innervated endplate. The extent of NMJ innervation was judged by assessing the extent to which labeling for neurofilaments (NF) extended into endplates. In this panel, ACHR-rich endplates are completely covered by S100 labeling (green) for TSCs as well as are preterminal SCs. All WT MG endplates were fully covered by S100 labeling independent of innervation status. B. B6.SOD1 MG endplates labeled for S100 and ACHRs 10 days after sciatic crush. No NF labeling (not shown) was observed at these ACHR-rich endplates or in the immediate preterminal regions demonstrating denervation. In this field, neither endplates nor preterminal regions exhibited S100 labeling for TSCs or for SCs. Green label reflects background labeling located between muscle fibers. C–E. Charts show mean percentage of NMJs for each of 3 innervation categories (I, innervated; P, partially innervated; F, fully innervated) at 10d after denervation compared between sciatic crush denervated and contralateral, control MG muscles for various data groups. Bar colors designate NMJ S100 coverage status; red bars indicate absence of labeling, yellow bars indicate partial coverage, black bars indicates full coverage. Asterisks placed in sciatic crush denervation side distributions indicate that sciatic crush and contralateral, control distributions differed significantly (Pearson chi-square, p < 0.01). At 10d, both B6.SOD1 (C) and WT MG (D) innervation remained significantly different from control sides but reinnervation of WT muscle appeared to be more progressed. All denervated B6.SOD1 MG NMJs remained completely uncovered by S100 labeling. As described in Results, SOD1G85R MG muscles (N = 2) were denervated and examined 10d later. The results (E) showed that denervated NMJs lacked S100 labeling, similar to results from B6.SOD1 (C). F. Example of S100 (F1) and P75 (F2) colabeling at an B6.SOD1 MG endplate 10 days after sciatic crush. Although SC processes can be seen approaching the endplate, the absence of both labels over the endplate indicates the absence of SC NMJ coverage. G1. Lower magnification view of B6.SOD1 MG endplate band labeled for S100 and ACHRs. No S100 labeling is observed over endplates or in preterminal regions. In the upper part of the panel, an S100+ group of SC processes can be seen demonstrating the nearby presence of SCs. G2. White outlined region in B2 labeled for S100 (green) and NF (red). Regenerating axons (yellow arrows) can be seen in close association with SC processes but extending no further than the leading edge of S100 labeling. H–J. Charts show mean percentage of NMJs for each of 3 innervation categories at 14 after denervation. By 14d, WT MG (I) is essentially reinnervated whereas B6.SOD1 MG remains mostly denervated (H). This indicates that reinnervation of B6.SOD1 muscles is slowed compared with reinnervation of WT muscle. J. MG muscles from SODWT mice (N = 4) were denervated and NMJ innervation and S100 coverage studied 14d later. Reinnervation was essentially identical to that observed in WT MG after 14d thus demonstrating that overexpression of mutated protein does not underlie denervation effects seen at B6.SOD1 MG NMJs.