Abstract

Objective

While at increased risk for developing dementia compared to whites, older African Americans are diagnosed later in the course of dementia. Using Common Sense Model (CSM) of Illness Perception, we sought to clarify processes promoting timely diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) for African Americans.

Design, Setting, Participants

In-person, cross-sectional, survey data were obtained from 187 African Americans, mean age 60.44 years. Data were collected at social and health-focused community events in three southern Wisconsin cities.

Measurements

The survey represented a compilation of published surveys querying CSM constructs focused on early detection of memory disorders, and willingness to discuss concerns about memory loss with healthcare providers. Derived CSM variables measuring perceived causes, consequences and controllability of MCI were included in a structural equation model (SEM) predicting the primary outcome: Willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with a provider.

Results

Two CSM factors influenced willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with providers. Anticipation of beneficial consequences and perception of low harm associated with an MCI diagnosis predicted a person’s willingness to discuss concerns about cognitive changes. No association was found between perceived controllability and causes of MCI, and willingness to discuss symptoms with a provider.

Conclusions

These data suggest that allaying concerns about the deleterious effects of a diagnosis, and raising awareness of potential benefits could influence an African American’s willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with a provider. The findings offer guidance to design culturally congruent MCI education materials, and to healthcare providers caring for older African Americans.

Keywords: Timely diagnosis, Mild Cognitive Impairment, African Americans, Common Sense Model, Structural Equation Modeling, Health Disparities

1. OBJECTIVE

While nearly twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as older White Americans, older African Americans are less likely to receive specialized diagnostic evaluations, and are diagnosed later in the course of the illness.(1–5) The barriers to timely diagnosis encountered by African Americans are multifactorial, representing both cultural beliefs about aging and cognitive decline, as well as disparities in access to diagnostic service, treatment practices, and accuracy of screening methods.(6)

Recent publicly-sponsored initiatives are focused on improving the timely diagnosis of dementia. (e.g., National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s disease (NAPA)), and Early Detection of and Timely Intervention of Dementia (INTERDEM)). However, an emerging consensus suggests that AD, the most common form of dementia, starts decades before the onset of symptoms.(7, 8) For this reason, it may be important to expand the scope of early detection efforts to include recognition of symptoms consistent with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition representing an intermediate stage between cognitive health and dementia.(9)

According to Leventhal’s Common Sense Model (10) (CSM), the decision to seek medical attention for a condition is influenced by one’s personal understanding of the illness, which in turn is organized around a set of five cognitive constructs, including 1) illness identity, 2) timeline, 3) causes, 4) consequences, and 5) controllability. In previous work,(11) we examined the illness perception of MCI using the CSM. In a sample of predominantly white adults with MCI, the illness identity was accurately portrayed as cognitive as opposed to physical and emotional in nature, and the timeline as chronic. Older adults with MCI felt their disease was controllable, and most reported the causes to be aging, genetic or hereditary, abnormal brain changes and stress. Overall, for individuals already diagnosed with MCI, illness identity, perception of causes, timeline, and controllability were well-articulated. In contrast, the expected consequences of the illness were highly variable. Importantly, the extent to which illness perception facilitated recognition of MCI for these older adults was not investigated.

This project sought to clarify the process through which African Americans obtain a timely diagnosis of MCI by examining perceptions of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of MCI in a sample of African Americans, using Leventhal’s CSM to characterize beliefs about MCI. A structural equation model (SEM) approach was used to test the influence of African American’s perceptions of causes, consequences (beneficial and harmful) and controllability of MCI on willingness to seek evaluation of symptoms. The CSM construct of causes refers to an individuals understanding of what leads to the development of MCI. We focused on a range of modifiable and fixed causes. Illness consequences describes to one’s perception of what will occur as a result of having the illness. In our project we queried participants’ perception of both beneficial and harmful consequences associated with a diagnosis of MCI. The CSM construct of controllability refers to whether individuals perceive the occurrence of disease as controllable. We assessed the construct by referencing controllable and uncontrollable risk factors for MCI. Because we provided participants with a description of MCI, as well as its corresponding symptoms and course, the CSM constructs of illness identity (i.e., the understanding of how the illness is manifested), and timeline (i.e., the nature of the disease course) were not included in our model. We hypothesized that perceiving causes of MCI as modifiable, consequences as beneficial, and the illness itself as controllable would associate with a willingness to discuss symptoms with a healthcare provider.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

Cross-sectional survey data were obtained in order to explore perceptions of memory loss, and willingness to discuss concerns about mild cognitive changes with healthcare providers. The University of Wisconsin’s Health Sciences Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all study procedures. After providing a complete description of the study to the subjects, the study team obtained informed consent from all participants.

2.2. Participants and Procedures

Data from 187 African Americans age 50 and over were available for analysis. Study personnel approached potential participants at community events, occurring in southern Wisconsin, and asked potential participants to complete a survey assessing attitudes about memory loss. In order to sample a broad spectrum of opinions, data were collected at both health-related and non-health related events. These included memory screening events sponsored by the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), as well as, social, non-health related community events, e.g., street fairs and church events.

The study team approached individuals who appeared to be middle-aged or older and African American, but we did not to exclude individuals based on age or self-identified race. Participants received $10 upon completion of the survey.

2.3. Questionnaire

A description of the diagnosis of MCI was provided to all subjects (See Supplemental Digital Text), followed by 54 survey questions compiled from five previously published questionnaires: 1) Anderson et al. (12) investigated white participants’ beliefs and perceptions about AD framed around the CSM; 2) Boustani et al. (13) investigated the attitudes about screening for memory loss in a diverse population (44% African American); 3) Dale et al. (14) surveyed attitudes about and willingness to be screened for MCI with a population-based sample that included whites and African Americans; 4) Galvin et al. (15) investigated attitudes about AD and memory screening in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults; and 5) Lin et al. (11) examined perception MCI using CSM of illness perceptions in sample of predominantly white older adults with MCI. Finally, additional questions developed by the research team members were also included.

Participants responded using a 4-point, bi-directional Likert scale, ranging from 1 (definitely no or strong disagreement) to 4 (definitely yes or strong agreement). In some instances, Likert scales were adjusted to maintain consistency of items within a section. Some items were re-worded to simplify language, and to query attitudes about MCI rather than AD. Finally, a narrative about a man who developed AD, originally included in the Anderson et al. (12) scale, was altered to reflect non-rural experiences, and the diagnosis of MCI, e.g., the main character’s profession was changed from farmer to mechanic, and his diagnosis from AD to MCI.

2.4. Variables – Common Sense Model (CSM) Constructs

Specific questions used to measure each of the CSM constructs are provided in a Supplemental Digital Table.

Causes of MCI

Items evaluating perceptions of the causes of MCI included both modifiable and fixed causes, as in the original Anderson et al. scale.(12) Modifiable causes included physical and mental inactivity, mental attitude (i.e., negative/positive way of thinking), and stress or worry. Inalterable Causes were family problems, overwork and personality. We summed responses, so that high scores signified agreement with the perception that causes were related to modifiable behaviors and factors within one’s control.

Consequences of MCI–Potential Harm

To evaluate the influence of perceived negative consequences, items adapted from the PRISM-PC (13) were selected and summed. Potential deleterious consequences related to stigmatizing attitudes: being treated poorly or perceived negatively by others; embarrassment; poor medical care; and loss of insurance. In total, six questions were selected to characterize potentially harmful consequences.

Consequences of MCI–Potential Benefits

To evaluate the influence of perceived beneficial consequences, items adapted from the PRISM-PC (13) were selected and summed. Potential benefits associated with a timely diagnosis of MCI included ability to prevent further cognitive decline; opportunity to marshal support from family members; time to plan for the future, and talk to family about health and financial preferences; time to establish advanced directives; and the opportunity to modify lifestyle and participate in research. Also included with this scale were items asking about interest in knowing personal risk for MCI. Reponses were totaled, with high scores reflecting a strong belief in the potential benefits of timely recognition of MCI.

Controllability of MCI

Six items from a scale used by and described in Anderson et al. (12), modified as described above, were used to derive an estimate of participants’ beliefs about the controllability of MCI. Participants were asked if they agreed/disagreed with statements such as, “A person can do a lot to control whether they get MCI;” “A person has the power to influence their chances of getting MCI;” and “Doing crossword puzzles can prevent MCI.” Two items, reflecting lack of control, were reversed scored and all items totaled. High scores indicated the belief that MCI was a controllable condition.

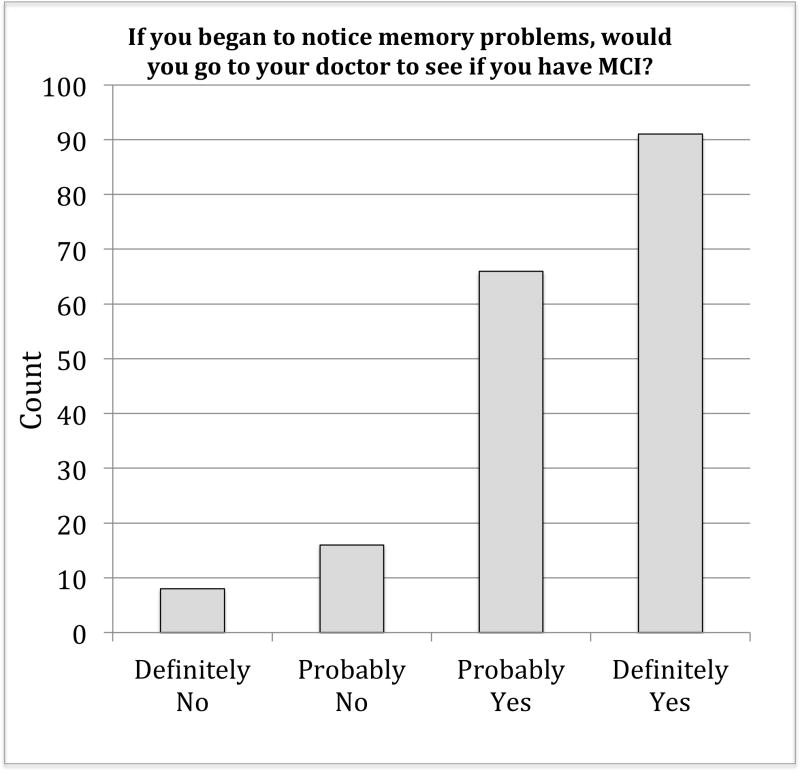

2.5. Variable – Willingness to Address Symptoms of MCI

After providing a narrative describing the syndrome of MCI, (Supplemental Digital Text), we posed a question originally included in Dale et al. questionnaires (14). Specifically, participants were asked, “If you began to notice problems with your memory, would you go see your doctor to see if you have MCI?” Categorical responses to this question ranged from (1) Definitely No to (4) Definitely Yes.

2.6. Analysis

Descriptive statistics for questionnaire data (mean, median, standard deviation) were obtained using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM, Version 22, Armonk, NY) software. The distribution of the items and the presence of floor and/or ceiling effects were also examined. Prior to model testing, constructs were examined using confirmatory factor analysis (16) (CFA), where items were analyzed as categorical measures with a weighted least-squares means and variance-adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, assuming that missing data for the observed variables occurred randomly. If a variable had a small loading on a factor, it was excluded from further analyses. Variables representing the constructs of (1) modifiable causes, (2) negative consequences, (3), beneficial consequences and (4) controllability were derived and included in the model.

We examined the associations between a set of demographic variables, constructed CSM factors, and our outcome of interest, willingness to discuss cognitive symptoms consistent with MCI with a healthcare provider, using a structural equation modeling (SEM). A multinomial probit model was used to test the effect of exogenous and endogenous variables on the outcome of willingness to report symptoms to a provider, and mean- and variance-adjusted WLSMV estimator to examine the effect of categorical variables, including our categorical outcome.

We hypothesized that demographic factors, such as gender, education, and age, influenced participants’ scores on each of these constructs. Therefore, we examined the association between 1) demographics and CSM construct measures, as well as 2) CSM constructs and willingness to seek a timely diagnosis of MCI. Of note, the full model examined 3) the associations between demographic variables and willingness to discuss concerns about memory with a provider, 4) the relationships between demographic variables, and 5) associations between CSM constructs. The tested model specified hypothesized directional relationships (regression paths) among the observed and construct or latent variables obtained from the CFA analysis. This SEM included latent predictors as endogenous variables.

The appropriateness of all models was evaluated by the χ2 test statistic and descriptive goodness of fit measures including the comparative fit index (17) (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (18) (TLI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (19) (RMSEA). All SEM analyses were conducted using the “lavaan” package in R.(20) We used two-tailed tests and a significance level of 0.05 to evaluate the significance of all paths.

3. RESULTS

Subject characteristics are provided in Table 1. On average, participants were middle-aged (mean age 60.44), mostly female (63.6%), and acquainted with individuals with dementia. For example, 122 (66.7%) of the 183 individuals responding to the question reported having spent time with someone with dementia. Likewise, our participants did not believe themselves to be at-risk for dementia with 123 (68.7%) stating that they did not believe that they were likely to develop dementia over their lifetime. Responses to our outcome question assessing willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with a healthcare provider are depicted in Figure 1. Overall, most of our older African American participants were willing to discuss concerns; however, approximately 13% (N=24) of our participants indicated that they were unlikely to report symptoms. An additional third (N=66, 35.3%) were inclined but equivocal regarding their willingness to report MCI symptoms to their healthcare provider.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| N | Value | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age in years (SD) | 187 | 60.44 (7.8) | 50–84 |

| N (%) Women | 187 | 119 (63.6%) | NA |

| Mean Education in years (SD) | 178 | 12.85 (2.3) | 6–20 |

| N (%) Self-reported Latino ethnicity | 121 | 9 (7.4%) | NA |

| N (%) Attending a screening event | 187 | 47 (25.1%) | NA |

| Income | 179 | ||

| N (%) <$30K annual household income | 113 (63.1.7%) | NA | |

| N (%) between $30K and $70K annual household income | 49 (27.4%) | NA | |

| N (%) ≥$70K annual household income | 10 (5.6%) | NA | |

| N (%) Not sure | 7 (3.9%) | ||

| N (%) who live alone more than half the time | 181 | 83 (45.9%) | NA |

Figure 1.

Responses to question assessing willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with a healthcare provider.

Participants enrolled at social versus health-focused events were not statistically different in age, gender representation, or education. Likewise, the two groups provided similar responses when asked if they would seek consultation if they noticed symptoms of MCI.

A CFA including previously published questionnaire items resulted in CSM latent factors assessing controllability,(12) consequences – benefits,(13) consequences – harms,(13) and causes.(12) A full list of items included in each of the factors is provided in the Supplemental Digital Table. Two questionnaire items originally included in the construct described by Anderson et al. as “controllability” did not contribute variance to the factor score in this sample, and were therefore excluded from analyses. The two questions asked for agreement to the statements: “There is nothing a person can do to affect whether they will get MCI,” and “A person’s actions will have no affect on whether a person will develop MCI.” For the three other factors: consequences – benefits, consequences – harms, and controllability, the items included in factor scores were consistent with published scales. Composite Reliability estimates (21) are provided in Supplementary Digital Table, and ranged from 0.71 for the causes factor to 0.96 for the consequences (Harmful) factor.

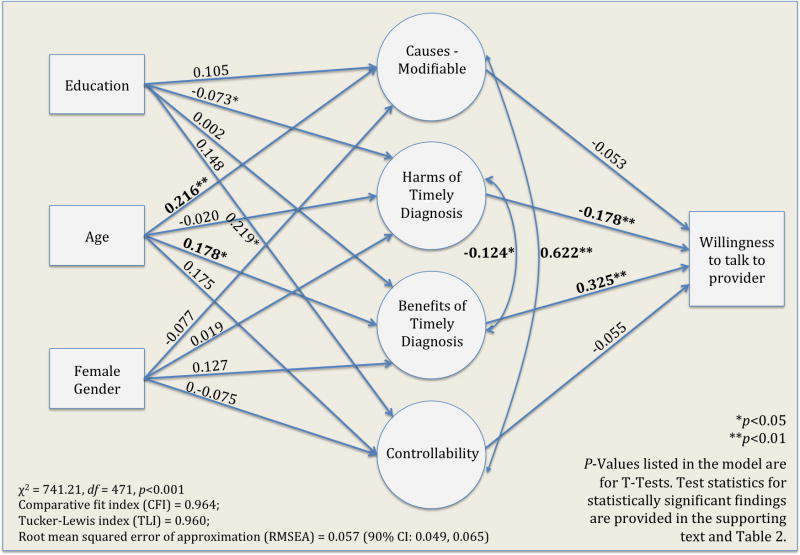

Hypothesized relationships between demographic and CSM latent variables and willingness to disclose symptoms of MCI to a provider were tested with a SEM. Fit indices suggested a reasonable error of fit (χ2 = 741.21, df = 471, p<0.001; Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.964; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.960; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) estimate = 0.057 with 90% CI: 0.049, 0.065; probability of the RMSEA was higher than 0.05, supporting acceptability of the proposed model.(22)) Overall, this panel of model fit tests (χ2, CFI, TLI and RMSEA) indicates that the model demonstrates good consistency with the data. Parameter estimates for this model are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Standardized associations and significance levels for SEM model presented in Figure 2.

| Path | Standardized Estimate (SE) | 2-Tailed p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | ||

| Age➞Causes–Modifiable | 0.216 (0.080) | 0.007 |

| Age➞Consequences–Harms | −0.020 (0.084) | 0.811 |

| Age➞Consequences–Benefits | 0.178 (0.076) | 0.019 |

| Age➞Controllability | 0.175 (0.096) | 0.069 |

| Age➞Willingness | −0.042 (0.074) | 0.570 |

| Education➞Causes–Modifiable | 0.105 (0.089) | 0.238 |

| Education➞Consequences–Harms | −0.081 (0.081) | 0.316 |

| Education➞Consequences–Benefits | 0.002 (0.081) | 0.976 |

| Education➞Controllability | 0.148 (0.108) | 0.171 |

| Educaiton➞Willingness | −0.027 (0.076) | 0.722 |

| Female Gender➞Causes–Modifiable | −0.077 (0.080) | 0.336 |

| Female Gender➞Consequences–Harms | 0.019 (0.084) | 0.821 |

| Female Gender➞Consequences–Benefits | 0.127 (0.078) | 0.101 |

| Female Gender➞Controllability | −0.075 (0.097) | 0.439 |

| Female Gender➞Willingness | 0.037 (0.073) | 0.610 |

| Common Sense Model Constructs | Standardized Estimate | 2-Tailed p-value |

| Causes–Modifiable➞Willingness | 0.053 (0.122) | 0.664 |

| Consequences–Harms➞Willingness | −0.178 (0.067) | 0.008 |

| Consequences–Benefits➞Willingness | 0.325 (0.061) | <0.001 |

| Controllability➞Willingness | −0.055 (0.132) | 0.675 |

NOTE: Willingness refers to willingness to seek consultation for symptoms of MCI from a healthcare provider. Model fit parameters: χ2 = 741.21, df = 471, p<0.001; Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.964; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.960; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.057 (90% CI: 0.049, 0.065). P-values correspond to two-tailed t-tests with df = 471. For significant findings, the t-statistics are as follows: Age on Causes-Modifiable, t = 2.70, df = 471, p = 0.007; Age on Consequences–Beneficial, t = 2.34, df = 471, p = 0.019); Consequences–Harms on Willingness, t = 2.66, df = 471, p = 0.008; and Consequences Benefits on Willingness, t = 5.33, df = 471, p < 0.001.

There were no significant relationships between the demographic variables gender, age and education and willingness to disclose symptoms; or between the individual demographic variables. Thus, the final model depicted in Figure 2 omits these associations. Likewise, there were no statistically significant relationships between gender, education and other variables. Age, on the other hand, was associated with the latent CSM variables causes and consequences – beneficial. In particular, older age was associated with the perception that MCI was caused by modifiable factors (causes in Figure 2) (standardized beta coefficient = 0.216, t = 2.70, df = 471, p = 0.007) and the belief that a timely diagnosis would have beneficial consequences (standardized beta coefficient = 0.178, t = 2.34, df = 471, p = 0.019).

Figure 2.

Simplified SEM Model results. The full model tested the influence of Common Sense Model (CSM) constructs and demographic factors on willingness to discuss symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with a healthcare provider. Demographic factors are modeled as exogenous variables (no arrows pointing to the variable) and latent CSM predictors as endogenous variables (represented as effects of demographic variables and predictors of willingness to talk to a provider). While all relationships between endogenous, exogenous variables, and the outcome variable were tested in the full model, only those relationships of interest are depicted in the simplified version of the model provided here.

Among the proposed latent CSM predictors, only two factors emerged as important influences on willingness to discuss symptoms of MCI with a provider. The anticipation of beneficial consequences and the belief in low risk for harmful consequences was associated with increased willingness to address concerns about cognitive changes with a health care provider. These associations were both statistically significant (standardized beta coefficient (benefits) = 0.325, t = 5.33, df = 471, p < 0.001 and standardized beta coefficient (harms) = −0.178, t = 2.66, df = 471, p = 0.008, respectively) (Table 2). Willingness to discuss concerns with a provider was unrelated to a person’s belief in the controllability of the illness and the belief that causes were modifiable.

4. DISCUSSION

Using Leventhal’s CSM of illness perception, the present study examined the influence of beliefs about the syndrome of MCI on willingness to discuss concerns about MCI with a provider. Leventhal’s CSM model (10) proposes that illness perception, be it negative, positive or neutral, is organized around five core concepts, and that these constructs influence how individuals react when confronted with symptoms of the illness. In this sample of African Americans, willingness to report symptoms consistent with MCI to a health care provider was primarily influenced by expectations about the consequences of receiving an MCI diagnosis. In particular, believing that early recognition of MCI is beneficial, and the risk for harm minimal, was associated with a willingness to disclose concerns to a provider. Neither the perception that MCI was controllable, nor the belief that the causes of the syndrome are modifiable was associated with willingness to voice concerns.

The present study provides unique insights regarding the perception of MCI in a sample of African Americans, and how illness perception may influence a key step in the diagnostic process: revelation of cognitive concerns to a provider. Not only is a subjective cognitive complaint by the patient or family a diagnostic feature of MCI,(23, 24) it an antecedent to accurate diagnosis. Specifically, diagnosis of MCI requires objective evidence of cognitive impairment, ideally established through formal diagnostic evaluation. This evaluation is typically initiated through the primary care provider. Admittedly, expressing concerns about cognitive changes to a provider may not be sufficient to obtain diagnostic evaluation; however, it is arguably a necessary first step. In other words, someone needs to “sound the alarm.”

In the case of dementia, African Americans are diagnosed later in the course of illness, compared to whites.(1–5) This delay in diagnosis is associated with financial and emotional costs, as well as, missed opportunities. Family members of both African American and white patients report that their diagnosis of dementia reduced uncertainty, and allowed time to involve the older adult in future plans.(25) Conversely, a delayed diagnosis prolonged the mis-attribution of dementia-related behaviors as volitional, and caused further distress.(26, 27) Timely diagnosis allows the patient to initiate pharmacological therapies and access dementia-related caregiver services, which reduce caregiver burden and delay institutionalization.(28–30) The substantial cost savings appreciated with delayed nursing home placement dwarf the additional cost associated with early medication use.(31) The need for early intervention as a means to reduce costs is emphasized by data suggesting that African Americans demonstrated the highest Medicaid cost of care associated with AD, compared to other racial groups.(32)

Interestingly, the influence of demographic factors in this select group of African Americans was limited to an influence of age. Altogether, older African American adults who acknowledged the benefits associated with timely diagnosis, and who recognize few risks associated with a diagnosis of MCI were more willing to seek consultation when symptoms occur. Likewise, older individuals in our cohort were more likely than younger individuals to believe in the benefits of a timely MCI diagnosis.

While others have examined attitudes about screening for MCI (14) and AD,(15) in diverse populations, including African Americans, no previous work has included the role of illness perception (i.e., CSM constructs) to examine behavioral intentions around MCI. Consequently, there is little known about the role of the illness perception in shaping African American’s willingness to seek consultation for symptoms of MCI. While our model proposed a complex interplay of demographic and CSM factors, the relationships between these variables and willingness to discuss concerns with a healthcare provider appeared relatively straightforward. In contrast, when CSM constructs were examined in relation to hypertension in a slightly younger group of African Americans, demographic variables, as well as the CSM constructs of causes and controllability predicted reported self-care behaviors.(33) While, both conditions often go unnoticed, increase risk for more serious illness, and are chronic, the illness representations for MCI and hypertension may differ too radically to be compared. Additionally the finding that controllability, be it of causes or the illness, did not influence the decision to seek consultation was surprising given data suggesting that the perception of control influences likelihood of seeking treatment other illness.(34)

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses

These data are among the first to describe how illness perception may influence discussions about MCI with providers, especially for African Africans. Our analysis addresses the prescient and urgent need to understand how we can improve timely recognition in this high-risk population. Still, there are limitations. The findings may not apply broadly to the African American population. Our data were collected from individuals from southern Wisconsin, who were willing to participate in the study. No systematic efforts were made to collect data from a representative sample, and bias was likely introduced in our non-random selection of survey participants. Moreover, this analysis focused only on barriers related to illness perception. Indeed there are other barriers related to access to services, mistrust of the medical system and providers, and other unmeasured socioeconomic barriers not included in our model. It is important to note effect sizes were modest, and the possibility for type 1 error exists given the multiple comparisons tested in our model. Finally, our data are cross-sectional and associational. We cannot presume causality from these associations. Nor can we definitively state that altering constructs will result in behavioral changes. While not complete in capturing the multitude of influences, these findings are a first step, providing key insights into the how illness perception is related to timely diagnosis.

4.2. Summary

These findings could be used to guide the design of outreach efforts. For example, education programs meant to facilitate timely detection of memory loss could explicitly include information about the benefits of early recognition of memory disorders. At the same time, programs should dispel unfounded concerns about the negative consequences and provide information on how to mitigate potentially deleterious consequences so that the individual’s concerns about stigma and mistreatment surrounding a diagnosis of MCI are fully addressed. Future research efforts could focus on examining methods to effectively influence the perception of risks and benefits of timely recognition.

This project part of a series of efforts directed toward a broader objective: To address health disparities in timely diagnosis through development of MCI screening methods that are appropriate, accurate, and culturally-sensitive and -congruent for African Americans. These data offer important insights and direction toward this goal.

Supplementary Material

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit and Factor Structure (N=187)

Supplemental Digital Text A: Information provided to participants prior to being asked questions related to their beliefs about Mild Cognitive Impairment. Text was adapted from a similar description used by Dale et al. (14).

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

This project was funded by the Wisconsin Partnership Program of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC; NIH-NIA grant P50-AG033514), and supported by the Madison VA Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). Additional support was provided by NCATS grant UL1TR000427 (PI: M. Drezner) via the UW Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) and resources and use of facilities at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Wisconsin ADRC Minority Recruitment Satellite Program, and the Education, Clinical and Administrative Cores of the Wisconsin ADRC, and the Community-Academic Aging Research Network (CAARN). Finally, we are grateful for the dedication and support from our Community Partners, Charlestine Daniel, MS and Paul Rusk from the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Alliance; staff Ornella Hills, and Tyrone Dickson from the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; project assistants, Paul Izard and Brianna Harris, and our participants.

GRECC Manuscript number: 2014-027

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, or any other funding agency.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Husaini BA, Sherkat DE, Moonis M, et al. Racial differences in the diagnosis of dementia and in its effects on the use and costs of health care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:92–96. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shadlen MF, Larson EB, Gibbons L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease symptom severity in blacks and whites. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:482–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thies W, Bleiler L. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark PC, Kutner NG, Goldstein FC, et al. Impediments to timely diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2012–2017. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knopman D, Donohue JA, Gutterman EM. Patterns of care in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease:Impediments to timely diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilworth-Anderson P, Pierre G, Hilliard TS. Social justice, health disparities, and culture in the care of the elderly. The Journal of law, medicine & ethics : a journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diefenbach MA, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of illness representation: Theoretical and practical considerations. J Soc Distress Homel. 1996;5:11–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin F, Gleason CE, Heidrich SM. Illness representations in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Research in gerontological nursing. 2012;5:195–206. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20120605-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson LN, McCaul KD, Langley LK. Common-sense beliefs about the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:922–931. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.569478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, et al. Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:812–820. doi: 10.1002/gps.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale W, Hougham GW, Hill EK, et al. High interest in screening and treatment for mild cognitive impairment in older adults: A pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1388–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galvin JE, Scharff DP, Glasheen C, et al. Development of a population-based questionnaire to explore psychosocial determinants of screening for memory loss and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:182–191. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson B. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentler PM. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiger JH, Lind JC. Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Iowa City, IA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosseel Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso A, Laenen A, Molenberghs G, et al. A unified approach to multi-item reliability. Biometrics. 2010;66:1061–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connell CM, Roberts JS, McLaughlin SJ, et al. Black and white adult family members’ attitudes toward a dementia diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1562–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vugt ME, Verhey FR. The impact of early dementia diagnosis and intervention on informal caregivers. Progress in neurobiology. 2013;110:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, et al. Caregivers’ perspectives on the pre-diagnostic period in early onset dementia: a long and winding road. International psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2011;23:1393–1404. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, et al. Early community-based service utilization and its effects on institutionalization in dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2005;45:177–185. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:937–944. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beusterien KM, Thomas SK, Gause D, et al. Impact of rivastigmine use on the risk of nursing home placement in a US sample. CNS drugs. 2004;18:1143–1148. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geldmacher DS, Kirson NY, Birnbaum HG, et al. Implications of early treatment among Medicaid patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilligan AM, Malone DC, Warholak TL, et al. Health disparities in cost of care in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis across 4 state Medicaid populations. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2013;28:84–92. doi: 10.1177/1533317512467679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickett S, Allen W, Franklin M, et al. Illness beliefs in African Americans with hypertension. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36:152–170. doi: 10.1177/0193945913491837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron L, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Symptom representations and affect as determinants of care seeking in a community-dwelling, adult sample population. Health Psychol. 1993;12:171–179. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit and Factor Structure (N=187)

Supplemental Digital Text A: Information provided to participants prior to being asked questions related to their beliefs about Mild Cognitive Impairment. Text was adapted from a similar description used by Dale et al. (14).