Abstract

Lifestyle choices influence 20–40 % of adult peak bone mass. Therefore, optimization of lifestyle factors known to influence peak bone mass and strength is an important strategy aimed at reducing risk of osteoporosis or low bone mass later in life. The National Osteoporosis Foundation has issued this scientific statement to provide evidence-based guidance and a national implementation strategy for the purpose of helping individuals achieve maximal peak bone mass early in life. In this scientific statement, we (1) report the results of an evidence-based review of the literature since 2000 on factors that influence achieving the full genetic potential for skeletal mass; (2) recommend lifestyle choices that promote maximal bone health throughout the lifespan; (3) outline a research agenda to address current gaps; and (4) identify implementation strategies. We conducted a systematic review of the role of individual nutrients, food patterns, special issues, contraceptives, and physical activity on bone mass and strength development in youth. An evidence grading system was applied to describe the strength of available evidence on these individual modifiable lifestyle factors that may (or may not) influence the development of peak bone mass (Table 1). A summary of the grades for each of these factors is given below. We describe the underpinning biology of these relationships as well as other factors for which a systematic review approach was not possible. Articles published since 2000, all of which followed the report by Heaney et al. [1] published in that year, were considered for this scientific statement. This current review is a systematic update of the previous review conducted by the National Osteoporosis Foundation [1].

| Lifestyle Factor | Grade |

| Macronutrients | |

| Fat | D |

| Protein | C |

| Micronutrients | |

| Calcium | A |

| Vitamin D | B |

| Micronutrients other than calcium and vitamin D | D |

| Food Patterns | |

| Dairy | B |

| Fiber | C |

| Fruits and vegetables | C |

| Detriment of cola and caffeinated beverages | C |

| Infant Nutrition | |

| Duration of breastfeeding | D |

| Breastfeeding versus formula feeding | D |

| Enriched formula feeding | D |

| Adolescent Special Issues | |

| Detriment of oral contraceptives | D |

| Detriment of DMPA injections | B |

| Detriment of alcohol | D |

| Detriment of smoking | C |

| Physical Activity and Exercise | |

| Effect on bone mass and density | A |

| Effect on bone structural outcomes | B |

Considering the evidence-based literature review, we recommend lifestyle choices that promote maximal bone health from childhood through young to late adolescence and outline a research agenda to address current gaps in knowledge. The best evidence (grade A) is available for positive effects of calcium intake and physical activity, especially during the late childhood and peripubertal years—a critical period for bone accretion. Good evidence is also available for a role of vitamin D and dairy consumption and a detriment of DMPA injections. However, more rigorous trial data on many other lifestyle choices are needed and this need is outlined in our research agenda. Implementation strategies for lifestyle modifications to promote development of peak bone mass and strength within one’s genetic potential require a multisectored (i.e., family, schools, healthcare systems) approach.

Keywords: Bone mineral content, Diet, Nutrition, Peak bone mass, Physical activity

Introduction

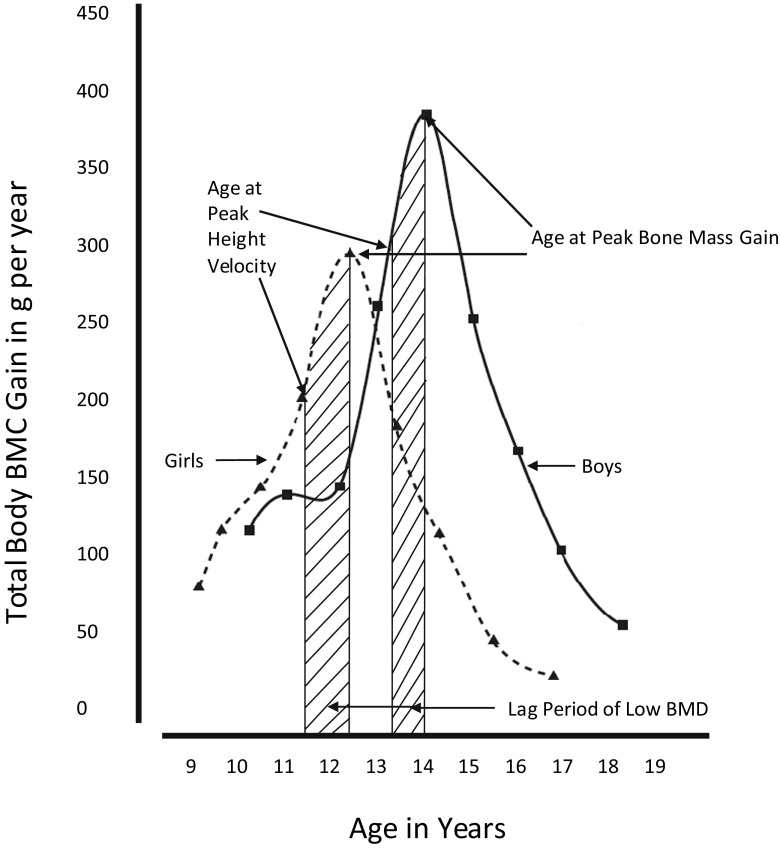

Bone accretion

During growth and development, skeletal growth proceeds through the coordinated action of bone deposition and resorption to allow bones to expand (periosteal apposition of cortical bone) and lengthen (endochondral ossification) into their adult form [2]. This process of bone modeling begins during fetal growth and continues until epiphyseal fusion, usually by the end of the second decade of life [1]. Bone modeling is sensitive to mechanical loading, emphasizing the importance of physical activity throughout growth [2]. Some skeletal characteristics, such as cortical density and structural strength, determined by bone dimensions and thickness, continue to increase after epiphyseal fusion and into the third decade of life. Quantitatively, the amount of bone mineral acquired from birth to adulthood follows distinct age- and sex-specific patterns (Fig. 1). Bone mass is acquired relatively slowly throughout childhood. With the onset of puberty and the adolescent growth spurt in height, bone mineral accretion is rapid, reaching a peak shortly after peak height gain (Fig. 2). For total body bone mineral, the peak bone mineral accretion rate occurs at 12.5 ± 0.90 years in girls and 14.1 ± 0.95 years in boys of European ancestry [3]. During the 4 years surrounding the peak in bone accretion, 39 % of total body bone mineral is acquired; by 4 years following the peak, 95 % of adult bone mass has been achieved [4]. Within a population, the distribution of bone mass becomes more variable, in part due to differences in height and other skeletal dimensions as adult size is attained, the timing and magnitude of peak bone mineral accrual, the cessation of bone accretion, and lifestyle factors. This period of rapid accretion may be a time of both opportunity and vulnerability for optimizing peak bone mass.

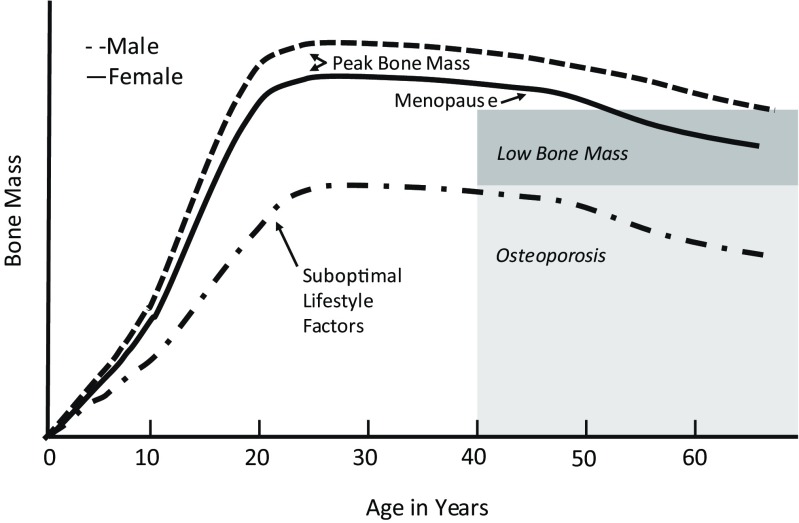

Fig. 1.

Bone mass across the lifespan with optimal and suboptimal lifestyle choices

Fig. 2.

Peak BMC gain and peak height velocity in boys and girls from longitudinal DXA analysis. Adapted from Bailey et al. [3]

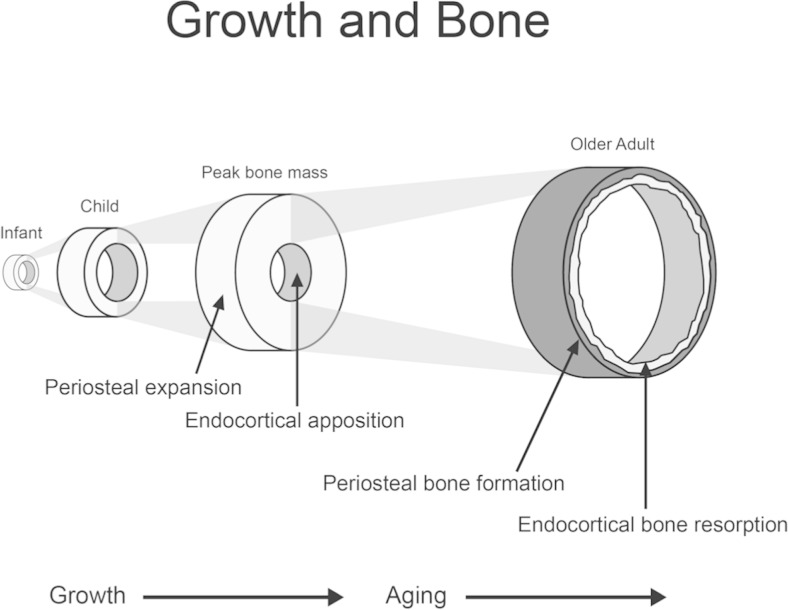

Changes in the structure (size and shape) and composition (amount of cartilage, cortical, and trabecular bone) of bone also occur with progression through puberty and thereby influence bone strength (Fig. 3). Cortical bone is the compact bone that forms the outer shell protecting bone marrow and trabecular bone. Trabecular bone is composed of rods and plates in a sponge-like structure, adding to the structural strength of bone. Cortical and trabecular bone differ in their responsiveness to disease effects, medications, muscle-loading and impact-loading physical activity, and hormonal changes. The relative importance of cortical versus trabecular bone in optimizing peak bone mass and strength and in minimizing fracture risk has not been firmly established in either childhood or adulthood. Distinct increases in trabecular bone of the spine and long bones occur between sexual maturity stages 3 and 4 [5–7]. The density of cortical bone is lower among children and adolescents than among adults, and it may even go through a transient period of increased porosity, particularly for boys [7, 8]. The density of cortical bone increases more rapidly as epiphyseal fusion occurs and continues into the third decade of life [9]. Both the inner and outer dimensions of long bones increase as growth proceeds, providing greater structural strength. The accumulation of bone mineral and changes in density and structural strength of bone may also continue into the third decade of life, depending on the bone compartment and skeletal site under consideration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Changes in structural composition of bone throughout the lifespan

Definition of peak bone mass

Peak bone mass is generally thought of as the amount of bone gained by the time a stable skeletal state has been attained during young adulthood. The concept of peak bone mass more broadly captures peak bone strength, which is characterized by mass, density, microarchitecture, microrepair mechanisms, and the geometric properties that provide structural strength.

There are several nuances to this concept that deserve recognition. The concept of peak bone mass is different when applied to an individual as opposed to a population. For an individual, peak bone mass may refer to the maximum amount of bone accrued during young adulthood. Alternatively, the concept of peak bone mass may refer to an individual’s maximal or genetic potential for bone strength (i.e., bone mineral content (BMC), areal bone mineral density (aBMD), or other measures of bone strength). At the population level, peak bone mass is attained when age-related changes in a bone outcome are no longer positive and have attained a plateau or maximum value [10].

Importance of peak bone mass

Fracture

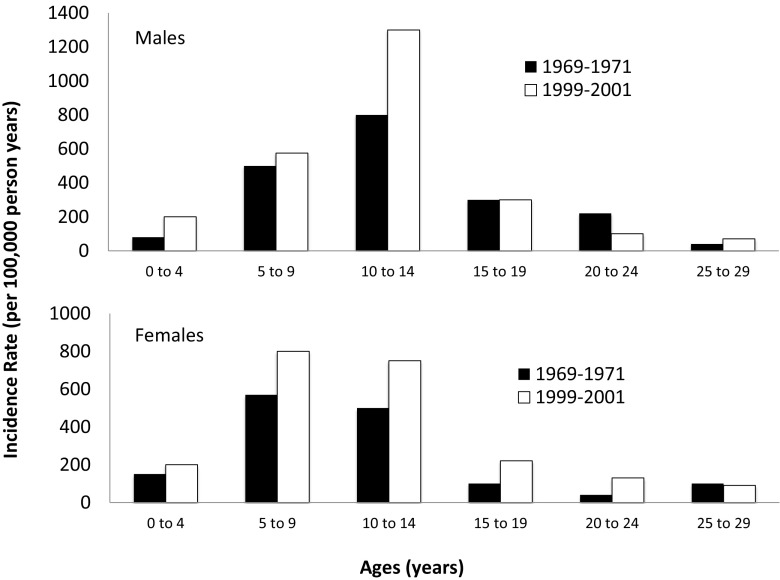

Optimizing bone accrual during growth may be of greatest significance in preventing current or future fractures, as measures of bone mass, density, and structural strength are associated with fracture in children and adults [11–13]. The frequency of fractures is higher among children compared to young and middle-aged adults [14], reflecting the vulnerability of the growing skeleton prior to peak bone mass. Among healthy children, as many as one half of boys and one third of girls will sustain a fracture by age 18 years, with one fifth sustaining two or more fractures [15, 16]. Children who sustain a fracture before age 4 years are especially vulnerable to a subsequent fracture [17]. Thirty to 50 % of childhood fractures involve the forearm [14, 15, 18–20] and result from falls to an outstretched arm. There is a positive relationship between fracture frequency and level of physical activity due to the increased risk of falls during physical activity [21]. Thus, although physical activity is critical for bone modeling, children with higher levels of physical activity are more likely to have fractures [3, 22–28].

There is a developmental period during the rapid growth of late childhood and early adolescence when the skeleton is particularly vulnerable to fracture (Fig. 4) [29]. Recently, high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HRpQCT) has been used to explain the microarchitectural basis for the observation of increased fracture frequency among young adolescents [7]. The combination of thinner cortical bone, lower total volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD), and increased cortical porosity, particularly in boys, suggests that linear bone growth outpaces bone mineralization, resulting in transient bone fragility.

Fig. 4.

Incidence of fractures of the distal forearm from birth through young adulthood. Adapted from Khosla et al. [29]

Understanding factors that affect bone strength early in life is important because low bone strength is associated with fracture risk in later life, independent of fall incidence and physical activity [30]. Childhood bone mass is predictive of fracture risk during childhood, with an 89 % increase in fracture risk per SD decrease in size-adjusted bone mass [31]. Moreover, among children who experience similar forearm injuries, those with greater bone density have been shown to be less likely to fracture [32]. Preterm children have low bone mass during late childhood [33], and birth weight is related to bone mass in later adult life (age ≥60 years) [34].

Recent work using HRpQCT suggests that microarchitectural changes underlie increased bone fragility in children who sustain a distal forearm fracture following mild trauma compared to nonfracture controls [35]. Differences such as cortical thinning are seen at both the distal radius and distal tibia in children presenting with a forearm fracture in which the degree of trauma is mild (e.g., fall from standing height), but not in those where the trauma is moderate (e.g., fall while riding a bicycle). Further analysis, including microfinite element analysis of HRpQCT data, showed that the mild trauma distal forearm fracture cases had reduced bone strength (i.e., failure load) compared to children without a fracture history. Moderate trauma is sufficient to break healthy bones that are not otherwise inherently at increased risk of fracture. Clark et al. [21] have shown that, irrespective of bone mass, fracture risk rises as the amount of vigorous activity increases. Additional studies have shown that a forearm fracture in a child is associated with lower areal and vBMD, cortical area, and bone strength using peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [11]. Cohort studies in the USA and South Africa show that boys and girls of European descent have a greater fracture risk than children of African descent [36, 37], a finding that parallels patterns of osteoporosis and hip fracture in elderly adults [38, 39].

In childhood and adolescence, stress fractures exhibit a different pattern from typical long bone fractures. The lifetime prevalence of stress fracture among the general population is below 4 % [40], and stress fractures are more common among women than among men [41]. In studies of military populations, where stress fractures are most common, the rate ratio may be 10:1 [42–47], with up to 20 % of female recruits in basic training reported to have sustained a stress fracture [44–48] (note: military studies include young adults aged ≥18 years). Risk factors for stress fractures among recruits include low quantitative ultrasound values, smoking, history of being sedentary [49], and volume of training [40, 44, 50]. White race and a reported family history of osteoporosis or osteopenia may also represent significant risk factors [51, 52].

Tracking

Tracking refers to the stability of a trait over time. The degree to which indicators of bone strength track from childhood to peak bone mass and beyond is of paramount importance to optimizing peak bone mass for lifelong skeletal health. If bone “status” (i.e., bone mass, density, or structural strength relative to one’s peers of the same age and sex) at any given time point were not associated with its future status, then concerns would only be relevant to prevention of childhood fractures, not osteoporosis later in life. In fact, numerous prospective studies have demonstrated that measures of bone density track quite strongly from childhood through adolescence, with tracking correlations ranging from 0.5 to 0.9 depending on the skeletal site, trait, and duration of follow-up, with most estimates falling in the range of 0.6 to 0.7 [32, 53–57]. Tracking correlations decline during adolescence and then rebound, a phenomenon that is likely due to variability in the timing of puberty and peak bone accrual. Adjustment for height status largely eliminates this transient decline in tracking [32, 57]. One study of children aged 8–16 years (n = 183) examined the factors associated with tracking deviation. Positive deviation (i.e., improvement in spine and hip aBMD tertile) was associated with having been breast-fed, gains in lean mass, aerobic fitness, and sports participation. Gains in adiposity were associated with negative deviations in tracking [55]. These findings provide strong evidence that bone status during childhood, when peak bone mass is accumulated, is indicative of bone status in young adulthood. However, the fact that tracking correlations are far from unity suggests that lifestyle factors can alter bone status in both positive and negative directions.

Timing of peak bone mass

If the magnitude of peak bone mass attained in young adulthood is an important predictor of osteoporosis later in life, then the timing of peak bone mass is also important because it defines the lifecycle phase during which peak bone mass can be optimized. Regardless of whether one is referring to peak bone mass of an individual or a population, the timing of peak bone mass varies by skeletal site. Estimates based on longitudinal studies are preferred over cross-sectional population studies for identifying the timing of peak bone mass because they capture the process of bone accretion. For example, using longitudinal observations and the plateau method, the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study identified the ages of peak bone mass for women; for lumbar spine aBMD, it was between the ages of 33 and 40 years, whereas ages of peak bone mass for total hip BMD were between 16 and 19 years [10].

Estimates of the timing of peak bone mass further depend on the parameters of bone (i.e., mass, density, geometry, microarchitecture) under consideration. Using quantitative computed tomography (QCT), Riggs et al. [9] showed that women aged 20–29 years (n = 15) were losing trabecular bone at a rate of 1–1.75 % per year at the distal radius and lumbar spine, but they were gaining cortical bone at a rate of 0.25 % per year in the tibia. By contrast, men (n = 8) in this age range did not exhibit significant changes in these outcomes [9]. Cross-sectional data on >1000 men, aged 18.0–20.9 years, in the Gothenburg Osteoporosis and Obesity Determinants Study suggest that aBMD of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total body did not increase with age, but positive age-related associations were observed for aBMD of the radius, cortical, and trabecular vBMD, and cortical thickness of the radius and tibia as measured by DXA and pQCT [58]. The positive association with cortical thickness was attributed to a smaller medullary diameter, and not to periosteal expansion.

Because the timing of peak bone mass and strength varies by skeletal site and bone compartment, it is important to establish and retain behaviors that contribute to skeletal health, including region-specific changes (e.g., hip, spine). Moreover, until the lifelong importance of peak bone mass is fully understood [52], it is prudent to assume that these behaviors are needed to sustain skeletal health through the life cycle.

Methods for measuring peak bone mass

Insights into the development of peak bone mass are based on studies using DXA and QCT. These measurement techniques characterize different aspects of bone strength; DXA primarily measures bone mass (or bone mineral content [BMC]) and aBMD, which are integrated measures of cortical and trabecular bone.QCT can provide distinct measures of cortical and trabecular vBMD, bone geometry (e.g., periosteal and endosteal circumference and structural strength) and, in some cases, microarchitecture.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

The vast majority of studies on peak bone mass have utilized DXA, a low-dose x-ray technology that measures the attenuation of x-ray beams as they pass through tissues of varying density. DXA is a two-dimensional imaging technique that uses a planar image to estimate bone area. This technology is ideal for use in children because it is rapid, safe, widely available, and precise, with effective dose ranges from 0.03 to 15.2 μSV [59]. Because of the smaller bone size and lower density of bones in growing children, special software has been developed by the major DXA manufacturers to measure aBMD and BMC in children. DXA does not measure vBMD but instead provides what is referred to as aBMD. Since DXA does not capture the depth of bone, it systematically underestimates vBMD in children with poor growth. For this reason, adjusting DXA measures of BMC and aBMD for stature is recommended [60, 61]. This adjustment serves to distinguish between gains in BMC or aBMD that are independent of gains in stature. In addition, cortical and trabecular bone are superimposed in the DXA image, thus providing a composite estimate of the mass and density of these two bone compartments.

Lack of agreement exists regarding whether BMC or aBMD should be the outcome of interest in bone accretion studies in children. BMC is determined, in large part, by bone size because it reflects the mineral content of one region or the entire skeleton; aBMD only partly adjusts for bone size and a size-related artifact remains [61]. Using spine QCT measures as a reference method, Wren and colleagues have shown that DXA BMC was a better measure to use in children (ages 6–17 years), particularly in prepubertal children, than aBMD [62]. We agree with those who argue that, to account for size in studies of children, it is best to use BMC adjusted for bone area [63, 64], height-for-age Z-score [61], lean mass [65, 66], or other combinations of anthropometric variables [64, 67, 68] or to use calculated bone mineral apparent density [69], because these provide a more accurate reflection of a child’s bone health.

DXA measures have also been used to estimate structural strength of the proximal femur using the hip structural analysis (HSA) algorithm [70]. HSA estimates subperiosteal width, cross-sectional area (CSA), and section modulus in the narrow neck, intertrochanteric region, and shaft of the proximal femur. These outcomes are associated with treatment effects in adults as well as disease and exercise effects in children and adolescents [71–73].

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography

DXA only partly describes bone strength, which is the broader concern for understanding peak bone mass. Other modalities are used to more directly measure vBMD, microarchitecture, and geometry. Many of these characteristics can easily be measured in children with relatively low radiation exposure (0.59–1.09 mSv) [74]. QCT and pQCT are three-dimensional techniques that also use attenuation of x-ray beams to construct bone images. Cortical and trabecular bone compartments vary in density, and the differential attenuation of x-ray beams in the three-dimensional reconstruction allows for separate determination of trabecular and cortical vBMD, as well as numerous other measures of bone geometry (e.g., total bone area, periosteal and endosteal circumference) and structural strength in compression, bending, and torsion (e.g., section modulus, strain–strength index). Full-sized computed tomography (CT) scanners are used to measure the spine and other sites, and dedicated pQCT scanners measure the radius, tibia, or distal femur. Newer HRpQCT scanners achieve sufficient resolution for building microstructural finite element models of whole bone failure load, a surrogate measure of bone’s resistance to fracture, as well as cortical porosity, and trabecular plate and rod microstructure [74].

Mechanical loading

Physical activity comprises any body movement produced by muscle contraction resulting in energy expenditure above a resting level [75]. Exercise is a more restrictive concept and is defined by planned, organized, and repetitive physical activity aimed at maintaining or enhancing one or more components of physical fitness or a specific health outcome, such as bone strength [68]. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reviewed in this scientific statement used targeted exercise as an intervention to improve bone strength, whereas most of the longitudinal studies measured physical activity, including active transportation and activities of everyday life [76]. Physical activity has long been regarded as behavior likely to influence bone health [77, 78]. Epidemiological and clinical trial research dating back more than two decades confirms the positive impact of regular physical activity on bone [3, 27, 78–81]. However, we are only beginning to quantify the specific dimensions, dose, and timing of physical activity needed for maximal bone strength. What is known, primarily from animal studies, is that increased mechanical loads placed on bone through both impact and muscle forces cause deformation (strains) of whole bone [82, 83]. These strains activate mechanosensitive cells (i.e., osteocytes), embedded within the bone, which signal molecules to activate osteoblasts and osteoclasts. The signaling begins the process of bone adaptation to changes in physical activity, as well as other mechanical loads (e.g., an increase in body weight). To initiate an osteogenic response, bone must be subjected to a strain magnitude that surpasses a threshold determined by the habitual strain range in the predominant loading direction. The threshold varies between individuals (and also bone sites) according to physical activity habits and other factors (e.g., maturity status). Thus, children and adolescents may respond differently to similar mechanical loading conditions. Inactive children may respond to low-impact loading and improve bone mass or structure, while more active children will need a higher mechanical load to promote a skeletal response [84].

The skeleton needs to be strong for load bearing and light for mobility. A manner of minimizing the amount of bone mass needed in a cross-section without decreasing strength is to modify the distribution of bone mass and therefore changing bone structure. Throughout life, but mainly during growth, periosteal apposition increases the diameter of long bones and endocortical resorption enlarges the marrow cavity. Cortical thickness is determined by the net changes occurring at the periosteal and endosteal surface of bone. However, even without an increase in cortical thickness, the displacement of the cortex increases bending strength because resistance to bending is proportional to the fourth power of the distance from the neutral axis. In addition to the independent effect of physical activity on mass and density, increased mechanical loading via physical activity may influence structural changes in bone to increase strength in response to the new loading condition [25, 73, 85].

Bone is most responsive to physical activities that are dynamic, moderate to high in load magnitude, short in load duration, odd or nonrepetitive in load direction, and applied quickly [84]. The load magnitude is produced by impact with the ground (e.g., tumbling or jumping), impact with an object (racquet sports), or muscle power moves such as the lift phase in jumping and vaulting. On the other hand, due to desensitization of the osteocytes, static loads and repetitive low-magnitude loads are not osteogenic [86–88]. Although physical activity is a modifiable factor that contributes to peak bone mass and strength, our understanding of how to quantify the dimensions of physical activity that are osteogenic (including frequency, intensity, time, and type) is incomplete.

Body composition

It is widely recognized that lean body mass is among the strongest correlates of bone mass, density, and structural strength during childhood [89–92]. During adolescence, the peak in total body lean mass accretion occurs just prior to peak bone mineral accretion [2, 93], although at specific sites, peak increases in lean mass and bone strength may be coordinated [94]. In the latter phase of the adolescent growth spurt, following the peak, continued gains in lean mass are strong predictors of increases in BMC [95].

A major challenge in understanding the relationship between lean mass and bone is that both lean mass and bone mass have a strong heritable component. A study of young adult twins (aged 23–31 years) found that additive genetic factors accounted for 87 % of the variation in total body BMD, 81 % of the variation in lean mass, and 69–88 % of the covariance between lean mass and BMD depending on the skeletal site. Population differences also provide evidence of genetic determinants of lean and bone mass. Cardel et al. [96] compared groups of African or European ancestry (n = 301, aged 7–12 years) using ancestry informative DNA markers and found that a greater amount of African admixture was associated with greater lean mass and BMC after adjusting for socioeconomic status, sex, age, height, race/ethnicity, and pubertal status.

The effect of fat mass on bone mineral accretion and attainment of peak bone mass is far more controversial. Generally, greater body weight increases the effects of weight-bearing activity on bone. As children grow and increase in weight, both lean and fat mass increase. To reduce the likelihood of confounding from the bone loading effects of lean mass, it is important to first account for the effect of lean mass on bone in order to determine the effects of fat mass.

The source of adipose tissue may be important in considering the effects of body composition on bone outcomes. Visceral adipose tissue has different metabolic effects compared to subcutaneous fat, and it may be deleterious to bone by reducing bone quality. Adipose infiltrations of muscle and bone marrow associated with excess adiposity also have adverse effects on bone. Muscle density measured by pQCT is lower when the fat content within muscle is increased.

Nonmodifiable factors

Genetics

An estimated 60–80 % of the variability in bone mass and osteoporosis risk is explained by heritable factors. aBMD is lower among daughters of women with osteoporosis [97] and in men and women with first-degree relatives who have osteoporosis [98]. The familial resemblance of BMC is expressed prior to puberty [99, 100]. Genome-wide association studies have identified more than 70 loci associated with adult bone density or fractures [101, 102]. However, only a few such studies have been conducted in children [1, 103–106]. Twin studies also suggest that genetic predisposition determines up to 80 % of peak bone mass; the remaining 20 % is modulated by environmental factors and sex hormone levels during puberty [107].

Population ancestry

In North America, ethnic differences in vBMD and aBMD have been reported in children [5, 108, 109]. Among individuals aged 9–25 years, aBMD was consistently greater at all sites for African Americans compared to other groups, whereas Caucasians had greater values than Asians and Hispanics. In studies comparing children of Asian, European, and Hispanic ancestry, group differences in BMC were attributable to differences in bone size [110–112]. Ethnic differences in the rate of BMD gain have also been observed [109]. Differences between Caucasians, Asians, and Hispanics are smaller than between blacks and other groups; thus, pediatric reference ranges for BMC and aBMD are presented for African Americans and non-African Americans, and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommends using race-specific reference ranges in childhood because they reflect genetic potential for bone accretion [60, 111]. Studies using QCT provide insights into the population ancestry differences in DXA measures by describing cortical bone dimensions and trabecular density [5, 113–115]. As noted earlier, trabecular density increases during puberty. The magnitude of the pubertal increase in trabecular density is greater in African-American individuals than in Caucasians, and African-American children have greater total femoral bone in cross-sectional analyses [5, 6, 115].

Sex

Among children and adolescents, males have greater BMC and aBMD than females. These differences become more pronounced with the onset and progression through puberty or at the ages that correspond to these maturational changes [108, 109, 116–118]. The exact age at which these differences emerge is unclear. Earlier studies of infants (aged ≤12 months) did not find sex differences in total body BMD [119, 120] or spine BMC and aBMD [121, 122]; however, males (aged 1–18 months) had greater total body BMC than females [123]. A recent study of infants and toddlers aged 1–36 months confirmed the absence of sex differences in aBMD in very young children but found greater BMC in males than in females. Sex differences in the body size of infants and toddlers may account for BMC differences and the absence of aBMD differences. By about 5 years of age, girls have lower values for spine and hip aBMD than boys, a finding that persists when adjusted for age, height, and weight [124].

Studies of bone strength by pQCT reveal a more complex pattern of sex differences. In a study of 665 healthy individuals aged 5–35 years, cortical BMC, periosteal circumference, and section modulus were lower in the 38 % site of the tibia for females compared with males across all stages of puberty. However, cortical vBMD was greater and endosteal circumference was lower in peripubertal and postpubertal females compared to males. These differences were not attributable to differences in muscle mass or bone size [115]. In a 20-month longitudinal study of 128 children across puberty, boys exhibited a 10 % greater increase in total area and cortical area compared to girls, but the increase in the size of the marrow cavity was significantly less for girls than for boys [125]. Further evaluation showed that sex differences in bone strength are primarily due to the 4–6 % greater bone area in boys, which is evident in prepubertal children [126]. HRpQCT studies of the radius show that girls have higher cortical vBMD in midpuberty and postpuberty (9.4 and 7.4 %, respectively) and lower cortical porosity than boys (−118 and −56 %, respectively) [127].

Maturation

Advancement through puberty is associated with increases in BMC and aBMD, as well as cortical and trabecular vBMD. Moreover, several studies suggest that the timing of maturation may affect peak bone mass, particularly in girls. For example, Gilsanz et al. [128] showed that earlier age of pubertal onset was associated with greater DXA BMC and aBMD at skeletal maturity in both boys and girls, independent of prepubertal BMC and aBMD values and duration of puberty. Chevalley et al. [129] found that girls who attained menarche earlier had higher aBMD at multiple skeletal sites prior to, during, and after puberty. A Canadian longitudinal study (depicted in Fig. 2) found that girls who mature early had 3–4 % more total body BMC at age 20 years than girls who matured at an average age. However, maturational effects were only observed at the total body and not at other sites; no maturational timing effects were observed in males [130]. The absence of a maturation timing effect on aBMD and BMC of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total body was confirmed in a study of Swedish military recruits in which young men were followed until age 24 years. However, as with girls, later puberty in boys was associated with lower radius aBMD (−4.2 %, by DXA), as well as lower cortical (−0.7 %) and trabecular vBMD (−4.8 %, by pQCT) [131]. The long-term consequences of the effect of pubertal timing on peak bone mass remain to be determined.

Modifiable factors

Diet and physical activity are the primary modifiable factors associated with bone health, although other lifestyle and environmental factors may also be at play. Here, we review these factors and their contribution to peak bone mass.

Although we separately address the contribution of physical activity to peak bone mass and strength, we address nutrient interactions with physical activity and their effects on bone in the respective nutrient discussions. Several narrative and meta-analysis review articles were recently published that also address the strength of the evidence for physical activity and bone development [132–137].

Scientific statement aims

In this scientific statement, we (1) report the results of an evidence-based review of the literature since 2000 on factors that influence achieving the full genetic potential for skeletal mass, (2) recommend lifestyle choices that promote maximal bone health throughout the lifespan, (3) outline a research agenda to address current gaps, and (4) identify implementation strategies.

Methods

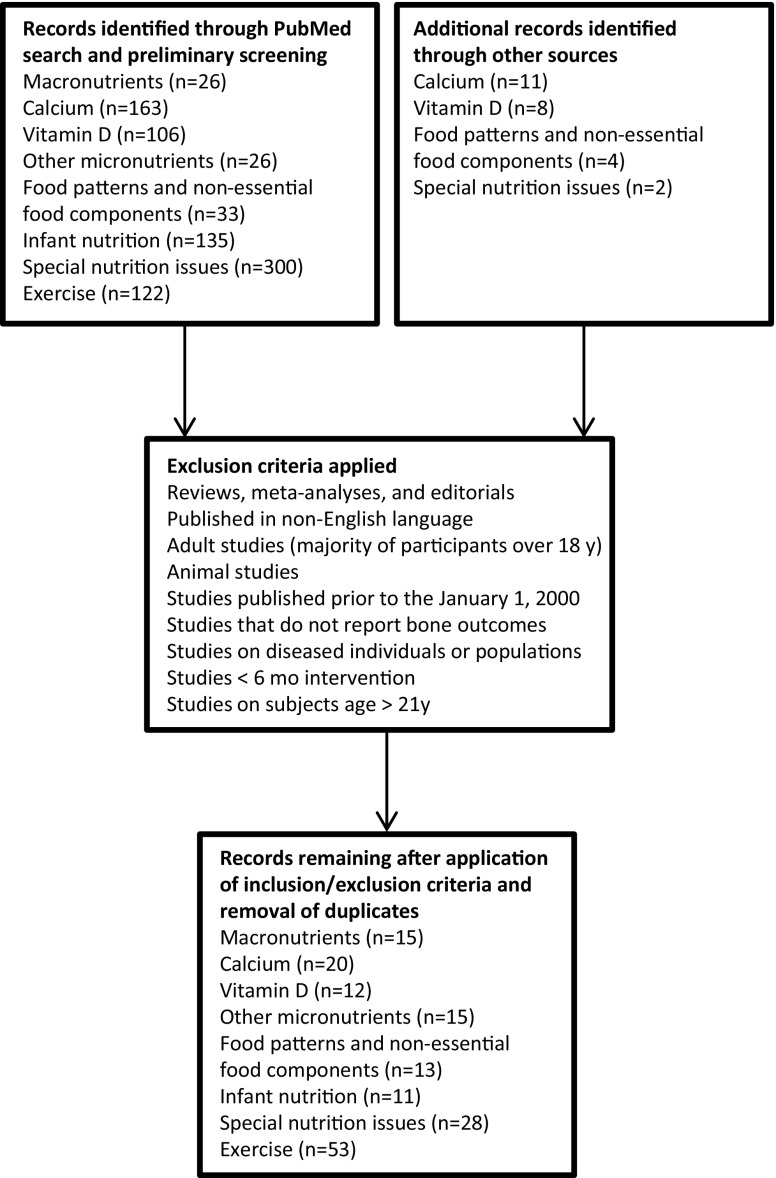

We performed a comprehensive PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) search of the scientific literature for articles published from January 2000 through December 2014. For all search terms, the following search strategy was used: ((((search term[Title/Abstract]) AND bone[Title/Abstract]) AND child*[Title/Abstract]) AND adolescen*[Title/Abstract]) NOT review[Publication Type]. Language, date, and species filters were then applied to the list of search results to eliminate articles not in English, articles published outside the 2000–2014 window, and animal studies. Searches for some of the topics required less restrictive searching in order to yield viable results, such as removal of the terms “child*” and/or “adolescen*,” or by expanding searches to scan terms found in “All Fields” rather than just “Title/Abstract.” MeSH terms were also utilized in some instances. Studies that contained subjects aged ≤21 years were included, except in the alcohol and smoking literature, in which studies that contained subjects aged ≤22 years were accepted due to lack of data in younger populations. Figure 5 represents the flow diagram of the systematic review for peak bone mass that includes search topics and the number of search returns.

Fig. 5.

Flow diagram of the systematic review on peak bone mass

To further narrow the search results for the broader topics (e.g., calcium, vitamin D, physical activity), we assigned authors to subcommittees based on their expertise and these subcommittees then reviewed the resultant abstracts. We excluded any articles that were not describing RCTs or observational studies, any studies that did not examine bone outcomes, and any interventions that were <6 months in duration. Studies and drug trials addressing disease states, with the exceptions of eating disorders and obesity, were likewise excluded. The articles that remained after the applications of these criteria were then rated based on the extent of scientific evidence as outlined in Table 1. This evidence grading system has previously been utilized by prominent organizations such as American Society for Nutrition [138] and the American Diabetes Association [139] and is recommended by other experts [140]. The assigned grade reflects the strength of available evidence on individual modifiable lifestyle factors that may (or may not) influence the development of peak bone mass. We assigned evidence grades after we achieved consensus among the writing group.

Table 1.

Evidence grading system

| Level of evidencea | Description |

|---|---|

| A: Strong | Clear evidence from at least one large, well-conducted, generalizable RCT that is adequately powered with a large effect size and is free of bias or other concerns |

| OR | |

| Clear evidence from multiple RCTs or many controlled trials that may have few limitations related to bias,measurement imprecision, inconsistent results, or other concerns | |

| B: Moderate | Evidence obtained from multiple, well-designed, conducted, and controlled prospective cohort studies that have used adequate and relevant measurements and that gave similar results from different populations |

| OR | |

| Evidence obtained from a well-conducted meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies from different populations | |

| C: Limited | Evidence obtained from multiple prospective cohort studies from diverse populations that have limitations related to bias, measurement imprecision, or inconsistent results or have other concerns |

| OR | |

| Evidence from only one well-designed prospective study with few limitations | |

| OR | |

| Evidence from multiple well-designed and conducted cross-sectional or case-controlled studies that have very few limitations that could invalidate the results from diverse populations | |

| OR | |

| Evidence from a meta-analysis that has design limitations | |

| D: Inadequate | Evidence from studies that have one or more major methodological flaws or many minor methodological flaws that result in low confidence in the effect estimate |

| OR | |

| Insufficient data to support a hypothesis | |

| OR | |

| Evidence derived from clinical experience, historical studies (before and after), or uncontrolled descriptive studies or case reports |

RCT randomized controlled trial

aRefers to the body of evidence

Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13

Table 2.

Fat and bone health in children and adolescents

| Macronutrient | Reference | Study description | Population description | Number of subjects | End points | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||||||||||

| Fat | Hogstrom et al. 2007 [141] | The objective of this study was to investigate the role of fatty acids in bone accumulation and the attainment of peak bone mass in young men | Sex: male Age: 16.7 years at baseline Race: white Location: Sweden Year(s): 1994 (baseline), first follow-up was at a mean of 6 years (age 22 years) |

78 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 78) | Total body | Hip | Spine | |||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | ||||||

| Palmitic acid | −0.04 | NS | 01 | NS | 0.01 | NS | |||||

| Palmitoleic acid | 0.04 | NS | 0.03 | NS | 0.02 | NS | |||||

| Stearic acid | 0.07 | NS | 0.02 | NS | 0.04 | NS | |||||

| Oleic acid | −0.19 | NS | −0.10 | NS | −0.22 | NS | |||||

| Linoleic acid | 0.00 | NS | −0.06 | NS | −0.15 | NS | |||||

| Eicosatrienoic acid | −0.09 | NS | −0.04 | NS | −0.08 | NS | |||||

| Arachidonic acid | 0.12 | NS | 0.15 | NS | 0.25 | <0.05 | |||||

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | 0.04 | NS | 0.02 | NS | 0.16 | NS | |||||

| Docosapentaenoic acid | 0.02 | NS | −0.07 | NS | 0.05 | NS | |||||

| DHA | 0.10 | NS | 0.07 | NS | 0.26 | <0.05 | |||||

| PUFA | 0.14 | NS | 0.07 | NS | 0.16 | NS | |||||

| MUFA | −0.18 | NS | −0.09 | NS | −0.21 | NS | |||||

| SFA | 0.04 | NS | 0.03 | NS | 0.05 | NS | |||||

| n-6 | 0.04 | NS | 0.00 | NS | 0.07 | NS | |||||

| n-3 | 0.10 | NS | 0.07 | NS | 0.26 | <0.05 | |||||

| n-6:n-3 | −0.12 | NS | −0.13 | NS | −0.26 | <0.05 | |||||

| Data presented above include Pearson’s correlations between fatty acids measured in the phospholipid fraction for changes in aBMD from 16 to 22 years | |||||||||||

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||||||||

| Fat | Eriksson et al. 2009 [142] | Serum phospholipid fatty acid pattern was studied in relation to bone parameters in healthy children | Sex: male and female Mean age: 8.2 years Race: Caucasian Location: Gothenburg, Sweden Year(s): not specified |

85 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 85) | Total body BMC (g) | |||||

| Correlation (r) | P | ||||||||||

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 0.17 | NS | |||||||||

| Stearic acid (18:0) | −0.15 | NS | |||||||||

| Arachidic acid (20:0) | 0.20 | NS | |||||||||

| Nervonic acid (24:1n-9) | 0.27 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) | −0.17 | NS | |||||||||

| Arachidonic acid (20:4n-6) | 0.23 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| α-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3) | −0.22 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| DHA (22:6n-3) | 0.03 | NS | |||||||||

| ∑ n-6 | −0.07 | NS | |||||||||

| ∑ n-3 | 0.03 | NS | |||||||||

| n-6:n-3 | −0.06 | NS | |||||||||

| Data presented above are from Pearson’s correlations | |||||||||||

25(OH)D 25-hydroxyvitamin D, aBMD areal bone mineral density, ANCOVA analysis of covariance, BMC bone mineral content, IGF insulin-like growth factor, NS not significant

Table 3.

Protein and bone health in children and adolescents

| Macronutrient | Reference | Study description | Population description | Number of subjects | End points | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | |||||||||||

| Protein | Ballard et al. 2006 [143] | This study investigated whether 6 months of protein supplementation in conjunction with a strength and conditioning training program improves vBMD, bone geometry, and total body BMC. | Sex: male and female Age: 18–25 years Race: not specified Location: South Dakota, USA Year(s): not specified |

68 | Data are shown for the protein supplemented group (n = 36) | Mean change, protein group (n = 36) | P | ||||

| 4 % site | |||||||||||

| Total vBMD (mg/cm3) | 0.20 | NS | |||||||||

| Trabecular vBMD (mg/cm3) | −0.50 | NS | |||||||||

| Total area (cm2) | 5.0 | NS | |||||||||

| 20 % site | |||||||||||

| Cortical vBMD (mg/cm3) | 2.4 | NS | |||||||||

| Cortical area (cm2) | 1.7 | NS | |||||||||

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.05 | NS | |||||||||

| Periosteal circumference (mm) | −0.20 | NS | |||||||||

| Endosteal circumference (mm) | −0.50 | NS | |||||||||

| Polar SSI (mm3) | 57 | NS | |||||||||

| Total body | |||||||||||

| BMC (g) | −3.5 | NS | |||||||||

| Bone area (cm2) | −3.9 | NS | |||||||||

| Leg | |||||||||||

| BMC (g) | 1.3 | NS | |||||||||

| Arm | |||||||||||

| BMC (g) | 5.7 | NS | |||||||||

| Data presented above are least-squares means determined by ANCOVA while controlling for initial height and weight and baseline bone value. | |||||||||||

| Prospective studies | |||||||||||

| Protein | Alexy et al. 2005 [144] | This study examined whether the long-term dietary protein intake and diet net acid load are associated with bone status in children. In a prospective study design, long-term dietary intakes were calculated from 3-day weighed dietary records that were collected yearly over the 4-year period before a one-time bone analysis using pQCT. | Sex: male and female Age: 6–18 years Race: white Location: Dortmund, Germany Year(s): 1998–1999 subcohort of the DONALD study |

229 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 229) | Protein (g/day) | |||||

| ß | ßstand | r 2 | P | ||||||||

| Forearm | |||||||||||

| Periosteal circumference (mm2) | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.03 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.04 | <0.01 | |||||||

| BMC (mg/mm) | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.03 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Polar SSI (mm3) | 1.83 | 0.29 | 0.06 | <0.01 | |||||||

| • Data presented above are results from stepwise multiple regression and after adjustment for age, sex, and energy intake. • ßstand is the standardized parameter estimate. • Children with a higher dietary PRAL had significantly less cortical area (P < 0.05) and BMC (P < 0.01). • Long-term calcium intake had no significant effect on any bone variable. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Bounds et al. 2005 [146] | This study aimed to identify factors related to children’s bone mineral indexes at age 8 years, and to assess bone mineral indexes in the same children at ages 6 and 8 years. Children’s dietary intake and BMC were assessed as part of a longitudinal study from ages 2 months to 8 years. | Sex: male and female Age: 6 years (baseline) and 8 years (follow-up) Race: white Location: Knoxville, TN Year(s): not specified |

52 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 229) | Protein intake (g) over ages 2–8 years | |||||

| r | P | ||||||||||

| Total body | |||||||||||

| BMC at age 8 years | 0.37 | ≤0.05 | |||||||||

| ß | Partial R 2 | P | |||||||||

| BMC model 1 | (+) 2.40 | 0.08 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Data presented above show the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) relating protein intake over ages 2–8 years, representing 27 days of dietary data. BMC model 1 (R 2 = 0.69, F = 20.7, P < 0.01) | |||||||||||

| Protein | Vatanparast et al. 2007 [147] | This mixed-longitudinal study investigated the influence of protein intake on bone mass measures in young adults, considering the influence of calcium intake through adolescence. Dietary intake was assessed via serial 24-h recalls carried out at least once yearly. | Sex: male and female Age: 8–21 years during phase I of the study; 17–29 years for phase II Race: majority Caucasian Location: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada Year(s): 1991–1997 (phase I); 2003–2006 (phase II); participating in the University of Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study |

133 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 133) and a subgroup (n = 44) | Protein intake (g) | |||||

| Regression coefficient | Partial R 2 | P | |||||||||

| Total body (N = 133) | |||||||||||

| BMC | NS | — | NS | ||||||||

| BMC net gain | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Total body (n = 44) | |||||||||||

| BMC | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| BMC net gain | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| The net gain of total body BMC and the net gains of height and weight from age of peak height velocity to early adulthood were entered into the model. Variables in the multiple regression model (stepwise) were sex, current height, weight, physical activity level, protein intake, vegetable and fruit intake, and periadolescence intakes of vegetables and fruit, protein, and physical activity. Protein intake predicted total body BMC net gain in all subjects. In females at periadolescence or early adulthood with adequate calcium intake(>1000 mg/day) (n = 44), protein intake positively predicted total body BMC and BMC net gain. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Zhang et al. 2010 [148] | This study assessed the association between protein intakes and bone mass accrual in girls who participated in a 5-year study including 2 years of milk supplementation (intervention groups only) and 3 years of follow-up study. | Sex: female Mean age: 10.1 years Race: Chinese Location: Beijing Year(s): 1999–2004 |

757 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 757) | Average protein intake | |||||

| ß | P value | ||||||||||

| Total body | |||||||||||

| Bone area | – | NS | |||||||||

| BMC | −1.92 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Proximal forearm | |||||||||||

| Bone area | −9.11 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| BMC | −10.2 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Distal forearm | |||||||||||

| Bone area | – | NS | |||||||||

| BMC | −4.82 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| • Data presented above (ß) represent the percentage change in the dependent variable associated with intake of protein after controlling for baseline bone mass and pubertal development, age and physical activity, survey time, group, and clustering by schools. Protein, among other nutrients, was included in an initial model and flowed by backward elimination with P < 0.01 as the standard for retention, exclusion by the regression model. • When protein intake was considered according to animal or plant food sources, protein from animal foods, particularly meat, had significant negative effects on BMC accrual at the proximal and distal forearm (P < 0.05). | |||||||||||

| Protein | Remer et al. 2011 [145] | The aim of the study was to examine whether the association of long-term dietary acid load and protein intake with children’s bone status can be confirmed using approved urinary biomarkers and whether these diet influences may be independent of potential bone-anabolic sex steroids. Data were collected in 197 healthy children during the 4 years preceding proximal forearm bone analyses by pQCT. | Sex: male and female Age: 6–18 years Race: white Location: Dortmund, Germany Year(s): 1998–1999 subcohort of the DONALD study |

197 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 197) | Urinary uN | Urinary PRAL | ||||

| ß | P | ß | P | ||||||||

| Forearm | |||||||||||

| BMC (mg/mm) [log 10] | 0.03 | <0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) [log 10] | 0.02 | <0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Polar SSI (mm3) [log 10] | 0.02 | <0.01 | −0.01 | NS | |||||||

| Periosteal circumference (mm) | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.02 | NS | |||||||

| BMD (mg/cm3) | 5.40 | NS | −8.70 | NS | |||||||

| • Data presented above are from multivariate regression models showing independent associations of both long-term protein intake (as uN) and PRAL as explanatory variables with forearm bone variables. Data are adjusted for age, sex, pubertal stage, forearm muscle area, forearm length, and urinary calcium. • Data show that 1 Z-score variation in uN leads to an average 7.2 % increase in BMC and a 4.7 % increase in cortical area as well as SSI. A 1 Z-score uN corresponds to 0.28-g protein intake/kg body wt, implying that an additional 1-g protein intake/kg body wt may lead to an average increase of 26 % in BMC and 17 % in cortical area and SSI. A 1-g protein intake/kg body wt is associated with an average increase of 1.8-mm periosteal circumference. | |||||||||||

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||||||||

| Protein | Hoppe et al. 2000 [149] | The objective of the study was to identify associations between dietary factors and total body bone measurements in a random sample of healthy Danish children. | Sex: male and female Age: 10 years Race: Danish, otherwise unspecified Location: Hvidovre, Denmark Year(s): 1997–1998, from the Copenhagen Cohort Study on Infant Nutrition and Growth |

105 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 105) | Protein (g/day) | |||||

| Pearson’s r | P | ||||||||||

| Total body | |||||||||||

| Bone area (cm2) | 0.31 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| BMC (g) | 0.33 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| • The data above are unadjusted. • In the multiple linear regression analysis including height, weight, sex, energy intake, and bone-related nutrients in the model, dietary protein was not significantly associated with bone area or BMC. After backward elimination, in which height, weight, and sex were forced to stay in the model, dietary protein was positively associated with bone area (P < 0.05). • Inclusion of pubertal stages in the analyses did not alter the bone area or BMC outcomes. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Iuliano-Burns et al. 2005 [150] | This cross-sectional study assessed monozygotic and dizygotic male twin pairs to test the following hypotheses: (1) associations between bone mass and dimensions and exercise are greater than between bone mass and dimensions and protein or calcium intakes; and (2) exercise or nutrient intake are associated with appendicular bone mass before puberty and axial bone mass during and after puberty. | Sex: male Age: 7–20 years Race: not specified Location: Melbourne, Australia Year(s): 1997–2001 |

112 (56 twin pairs) | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 112) | Differences in protein | |||||

| Univariate | Size adjusted | All lifestyle and size adjusted | |||||||||

| ß | P | ß | P | ß | P | ||||||

| Differences in BMC (g) | |||||||||||

| Total body | 3.5 | NS | 1.3 | NS | 1.3 | NS | |||||

| Arms | 0.8 | <0.05 | 0.7 | <0.05 | 0.8 | <0.05 | |||||

| Legs | 1.6 | NS | 0.3 | NS | 0.3 | NS | |||||

| Lumbar spine | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | |||||

| Differences in BMC (%) | |||||||||||

| Total body | 0.3 | <0.05 | 0.2 | <0.05 | 0.1 | NS | |||||

| Arms | 0.4 | <0.05 | 0.4 | <0.01 | 0.4 | <0.05 | |||||

| Legs | 0.3 | NS | 0.1 | NS | 0.1 | NS | |||||

| Lumbar spine | 0.1 | NS | 0.1 | NS | 0.2 | NS | |||||

| Differences in bone dimensions (mm) | |||||||||||

| Cortical thickness | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | |||||

| Periosteal diameter | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | |||||

| Endosteal diameter | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | −0.0 | NS | |||||

| Differences in bone dimensions (%) | |||||||||||

| Cortical thickness | 0.2 | NS | 0.1 | NS | 0.4 | NS | |||||

| Periosteal diameter | 0.1 | NS | 0.0 | NS | 0.0 | NS | |||||

| Endosteal diameter | −0.0 | NS | −0.1 | NS | −0.3 | NS | |||||

| • Data presented above are ß coefficients for within-pair differences in protein versus (1) within-pair differences in BMC and bone dimensions, (2) within-pair differences in size-adjusted BMC and bone dimensions, and (3) when all within-pair differences in protein, calcium, exercise duration, and size are included in the regression equation. • A 1-g difference in protein intake was associated with a 0.8-g (0.4 %) difference in arm BMC (P < 0.05). These relationships were present in peripubertal and postpubertal pairs but not in prepubertal pairs. Exercise during growth appears to have greater skeletal benefits than variations in protein or calcium intakes, with the site-specific effects evident in more mature twins. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Chevalley et al. 2008 [151] | This study analyzed the relationship between physical activity levels and protein compared with calcium intake on BMC in healthy prepubertal boys. | Sex: male Age: 6.5–8.5 years Race: white Location: Geneva, Switzerland Year(s): recruitment period 1999–2000, otherwise unspecified |

232 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 232) | Correlation with protein intake (g/day) | |||||

| r | P | ßAdjusted | P | ||||||||

| BMC (g) | |||||||||||

| Radial metaphysis | 0.26 | <0.01 | 0.20 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Radial diaphysis | 0.21 | <0.01 | 0.12 | NS | |||||||

| Total radius | 0.27 | <0.01 | 0.20 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Femoral neck | 0.20 | <0.01 | 0.19 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Total hip | 0.18 | <0.01 | 0.12 | NS | |||||||

| Femoral diaphysis | 0.23 | <0.01 | 0.19 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Lumbar spine | 0.24 | <0.01 | 0.22 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Data presented above are from univariate (r) and multivariate (ßAdjusted) analyses; the latter takes into account the respective contribution of physical activity, protein, and calcium intakes. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Esterle et al. 2009 [152] | This study explored dietary calcium sources and nutrients possibly associated with lumbar bone mineralization and calcium metabolism in adolescent girls and evaluated the possible influence of a genetic polymorphic trait associated with adult-type hypolactasia. | Sex: female Age: 12–22 years Race: Caucasian Location: France Year(s): not specified |

192 | Data are shown for the postmenarchal group only (n = 142) | Protein from milk | Protein from other foods | ||||

| Adj R 2 | ßstand | P | Adj R 2 | ßstand | P | ||||||

| Lumbar spine BMC (g) | |||||||||||

| Absolute | 0.61 | 0.14 | <0.01 | 0.61 | <0.01 | NS | |||||

| Adjusted | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.60 | <0.01 | NS | |||||

| • Data presented above are from multivariate linear analyses. • Absolute protein intake is expressed in g/days. • Adjusted protein intake for weight, years after menarche, and vertebral area is expressed in g/kg/days. • Girls with milk intakes <55 mL/day had significantly lower BMC compared to girls consuming >260 mL/day. • Neither BMC nor milk consumption was associated with −13,910 LCT polymorphism. | |||||||||||

| Protein | Ekbote et al. 2011 [153] | The aim of this study was to examine lifestyle factors as determinants of total body BMC and bone area in Indian preschool children. | Sex: male and female Age: 2–3 years Race: Indian Location: Pune, India Year(s): 2009 |

71 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 71) | Protein (g/days) | |||||

| Normal | Malnourished | All | |||||||||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | ||||||

| Total body | |||||||||||

| Bone area | 0.65 | <0.01 | 0.57 | <0.01 | 0.58 | <0.05 | |||||

| BMC | 0.62 | <0.01 | 0.44 | <0.05 | 0.55 | <0.01 | |||||

| Data presented above are from Pearson’s correlation coefficients correlating protein intake and bone among normal children, malnourished children, and all (normal and malnourished children combined). | |||||||||||

| Protein | Libuda et al. 2011 [154] | This study examined relevant nutrients that are supposed to have an impact on bone parameters and compared their effect sizes with those of known predictors of bone development. | Sex: male and female Median age: 8.1 years Race: white Location: Dortmund, Germany Year(s): 1998–1999 subcohort of the DONALD study |

107 | Data are shown for the overall group (N = 107) | Protein (g/MJ) | |||||

| ß | ßstand | R 2 | P | ||||||||

| Forearm | |||||||||||

| Polar SSI (mm3) | – | – | – | NS | |||||||

| Periosteal circumference (mm) | – | – | – | NS | |||||||

| BMC (mg/mm) | 1.49 | 0.11 | 0.01 | NS | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) | 1.37 | 0.11 | 0.01 | NS | |||||||

| • Data presented above are from stepwise linear regression analyses, considering muscle area, BMI standard deviation scores, body fat %, age, sex, and rostenediol, as well as intakes of protein, calcium, vitamin D, and PRAL. • Of all nutrients considered, only protein showed a trend for an association with BMC (P = 0.073) and cortical area (P = 0.056) in stepwise linear regression models. • None of the other dietary variables were associated with bone parameters. • The protein effect did not differ between sexes. | |||||||||||

Adj adjusted, ANCOVA analysis of covariance, BMC bone mineral content, BMD bone mineral density, DONALD Dortmund Nutritional and Anthropometric Longitudinally Designed Study, NS not significant, pQCT peripheral quantitative computed tomography, PRAL potential renal acid load, RCT randomized controlled trial, SSI stress–strain index, uN urinary nitrogen, vBMD volumetric bone mineral density

Table 4.

Calcium and bone health in children and adolescents

| Nutrient | Reference | Study description | Population description | Number of subjects | End points | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | ||||||||

| Supplements | ||||||||

| Calcium carbonate, 1000 mg/day | Dibba et al. 2000 [160] | 12-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study Supplementation increased calcium intake from 342 to 1056 mg/day By young adulthood, there was no difference in the amount of bone accrued (mineral or size) or the rate of bone growth between supplemented and placebo. |

Sex: 80 boys, 80 girls Age: 8.3–11.9 year Race: Gambian, otherwise unspecified Location: rural Gambia, West Africa |

160 | Difference in % gain between groups | |||

| Midshaft arm BMC | 4.6 ± 0.9a | |||||||

| Distal radius BMC | 5.5 ± 2.7a | |||||||

| Adjusted for bone width, weight, and height | ||||||||

| Calcium carbonate, 800 mg + 400 IU vitamin 3/day | Moyer-Mileur et al. 2003 [163] | 1-year double-blind RCT Baseline calcium: not reported Average intake during study: supplement, 1524 (353); placebo, 906 (345); 30 % dropout Trabecular vBMD values were significantly greater in the supplemented group at baseline. |

Sex: female Age: 12 years; Tanner stage 2 Race: white Location: USA |

100 | Tibial pQCT measurements | Calcium and D | Placebo | |

| Trabecular vBMD % increasea | 1.0 | −2.0 | ||||||

| Trabecular BMC % increasea | 4.1 | 1.6 | ||||||

| Adjusted for baseline values | ||||||||

| Elemental calcium, 1000 mg/day | Rozen et al. 2003 [330]; Dodiuk-Gad et al. 2005 [331] | 12-month double-blind, placebo-controlled Habitual calcium intakes <800 mg/day Compliance dropped from 71 ± 26 % during the initial 6 months to 56 ± 34 % for the remaining study period (P = 0.0001) In follow-up study by Dodiuk-Gad et al., girls who have had compliance of ≥75 % on supplementation had significantly higher total body BMD after 3.5 years after supplementation than controls. |

Sex: female; >1 year postmenarchal Age: 12–17 years Race: 85 Jewish girls and 27 Arab girls Location: Haifa, Israel |

112 | Calcium supplement | Placebo | ||

| Lumbar spine BMC | 4.52 ± 0.48 | 3.95 ± 0.58 | ||||||

| Total body BMC | 4.63 ± 0.42 | 4.65 ± 0.54 | ||||||

| Femoral neck BMC | 4.30 ± 0.86 | 3.00 ± 0.81 | ||||||

| Lumbar spine BMD | 3.66 ± 0.35a | 3.00 ± 0.43 | ||||||

| Total body BMD | 3.80 ± 0.30a | 3.07 ± 0.29 | ||||||

| Femoral neck BMD | 2.00 ± 0.51 | 1.39 ± 0.42 | ||||||

| Not adjusted | ||||||||

| Calcium carbonate (Caltrate) supplement, 1200 mg/day | Cameron et al. 2004 [161] | 24-month RCT of twins Baseline calcium intake: 786, trt; 772, control in those who completed 24 months All were premenarchal at baseline 24 (38 %) of pairs completed 24 months Compliance was 76 % for both groups |

Sex: female Age: 8–13 years Race: not specified Location: Australia |

103 (50 twin pairs + 1 set of triplets) |

End of 24-month intention to treat | Difference in % gain between groups | ||

| Total body BMC | 3.69a | |||||||

| Hip BMD | −0.39a | |||||||

| Spine BMD | 1.40a | |||||||

| Femoral neck BMD | −0.57 | |||||||

| End of 12 months | ||||||||

| Total body BMC | 2.47a | |||||||

| Hip BMD | 1.64a | |||||||

| Spine BMD | 1.64a | |||||||

| Femoral neck BMD | 1.13 | |||||||

| Adjusted for age, height, and weight | ||||||||

| Calcium carbonate, 500 mg/day | Molgaard et al. 2004 [332] | 12-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention Subjects stratified at randomization according to baseline calcium intake Group A (n = 60) habitually consumed 1000–1307 mg/day (40th–60th percentile), and group B (n = 53) habitually consumed <713 mg/day (<20th percentile) |

Sex: female Age: 12 years ± 6 months Race: white Location: Denmark |

113 | No significant interaction between habitual calcium intake (groups A and B) and the intervention (Calcium carbonate–Placebo) in the analyses of height, weight, BMC, size-adjusted BMC, bone area, or BMD (all P > 0.15). When groups A and B were analyzed together, there was a significant effect of the intervention on BMD (0.8 %; 95 % CI, 0.01 %, 1.54 %; P = 0.049). |

|||

| Calcium citrate malate, 1000 mg/day | Matkovic et al. 2005 [333] | 4-year randomized clinical trial and optionally extended for an additional 3 years Baseline calcium: 830 ± 236 mg/day 51 % of the subjects completed the 7-year trial. |

Sex: female Age: 11 years; Tanner 2 Race: white Location: USA |

354 | Calcium supplement | Placebo | ||

| End of 4-year gain | ||||||||

| Total body BMD (g/cm2) | 0.215 ± 0.037a | 0.204 ± 0.0353 | ||||||

| Proximal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.167 ± 0.088 | 0.171 ± 0.079 | ||||||

| Distal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.106 ± 0.047a | 0.092 ± 0.046 | ||||||

| Cortical area/total area | 0.079 ± 0.021 | 0.072 ± 0.0213 | ||||||

| End of 7-year gain | ||||||||

| Total body BMD (g/cm2) | 0.268 ± 0.049 | 0.263 ± 0.044 | ||||||

| Proximal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.162 ± 0.038 | 0.156 ± 0.036 | ||||||

| Distal radius BMD (g/cm2) | 0.171 ± 0.047 | 0.165 ± 0.040 | ||||||

| Cortical area/total area | 0.095 ± 0.025a | 0.085 ± 0.0242 | ||||||

| By young adulthood, significant effects remained at metacarpals and at the forearm of tall persons. | ||||||||

| Calcichew, 1000 mg/day | Prentice et al. 2005 [162] | 13-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study Subjects were stratified by high or low exercise at baseline. Those in the low group were randomized to exercise intervention or none. Compliance with exercise was poor and no statistically significant differences were found between groups. For final analysis, all exercise intervention groups were combined. Subjects were told to not take the supplement with meals. Baseline calcium: 1197, supplement; 1199, placebo Total calcium intake during study: supplement, 1858 ± 629; placebo, 1283 ± 586 Latter factored in compliance |

Sex: male Age: 16–18 years Race: 90 % white; 10 % from various ethnic groups Location: Cambridge, UK |

143 | Difference in % gain between groups | |||

| Total body BMC | 0.33 ± 0.34 | |||||||

| Lumbar spine BMC | 0.18 ± 0.54 | |||||||

| Total hip BMC | 1.09 ± 0.54a | |||||||

| Femoral neck BMC | 1.21 ± 0.65 | |||||||

| Intertrochanter BMC | 0.99 ± 0.56 | |||||||

| Trochanter BMC | 0.29 ± 0.80 | |||||||

| Ultradistal radius BMC | 0.36 ± 0.86 | |||||||

| Adjusted for bone area, weight, and height | ||||||||

| Calcium carbonate, 800 mg/day and vitamin D3 400 IU/day | Greene and Naughton 2011 [164] | 6-month randomized placebo-controlled trial Baseline calcium: 763–786 mg/day |

Sex: female; identical twins Age: 9–13 years Race: not indicated Location: Australia |

40 (20 pairs) | pQCT | Tibial difference in % gain between groups | ||

| 4 % location | ||||||||

| Trabecular vBMD (mg/mm3) | 5.2 ± 1.96a | |||||||

| Trabecular area (mm2) | 5.4 ± 1.33a | |||||||

| Subcort density (mg/mm3) | 3.4 ± 0.82 | |||||||

| Subcortical area (mm2) | 0.8 ± 0.07 | |||||||

| SSI (mm3) | 6.6 ± 1.26a | |||||||

| 14 % | ||||||||

| Cortical BMD (mg/mm3) | 0.1 ± 0.04 | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) | 1.3 ± 0.35 | |||||||

| Total bone area (mm2) | 0.3 ± 0.02 | |||||||

| Medullary CSA (mm2) | −0.4 ± 0.02 | |||||||

| SSI (mm3) | 1.7 ± 0.22 | |||||||

| 38 % | ||||||||

| Cortical BMD (mg/mm3) | 0.8 ± 0.03 | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) | 5.8 ± 0.8a | |||||||

| Total bone area (mm2) | 0.5 ± 0.03 | |||||||

| Medullary CSA (mm2) | −6.2 ± 1.6a | |||||||

| SSI (mm3) | 0.7 ± 0.06 | |||||||

| 66 % | ||||||||

| Cortical BMD (mg/mm3) | 0.1 ± 0.02 | |||||||

| Cortical area (mm2) | 5.7 ± 0.39a | |||||||

| Total bone area (mm2) | −0.7 ± 0.03 | |||||||

| Medullary CSA (mm2) | −8.1 ± 1.82a | |||||||

| Muscle CSA (mm2) | 0.6 ± 0.02 | |||||||

| Radial difference in % gain between groups | ||||||||

| 4 % location | ||||||||

| Trabecular vBMD (mg/mm3) | 3.3 ± 0.28a | |||||||

| Trabecular area (mm2) | 2.8 ± 0.36a | |||||||

| Subcortical density (mg/mm3) | 0.1 ± 0.03 | |||||||

| Subcortical area (mm2) | 0.3 ± 0.01 | |||||||

| SSI (mm3) | 5.7 ± 0.51a | |||||||

| Calcium carbonate pills | Khadilkar et al. 2012 [334] | 1-year double-blind RCT of calcium, multivitamin with zinc, and vitamin D3 | Sex: female Age: 8–12 years Race: Indian Location: Pune, India |

214 | Total body BMC increase | Percent gain by group | ||

| Calcium + multivitamin | Calcium | Control | ||||||

| 21.5 ± 5.7a | 23.1 ± 6.1a | 19.4 ± 4.2 | ||||||

| Adjusted for Tanner stage and lean body mass | ||||||||

| Calcium, 1000 mg/day by pill or cheese Vitamin D, 800 IU/day |

Cheng et al. 2005 [159] | 2-year RCT; randomized to 1 of 4 groups: calcium 1000 mg/day + vitamin D 200 IU/day; calcium 1000 mg/day; cheese (1000 mg/day); placebo Baseline calcium 664–680 mg/day |

Sex: female Age: 10–12 years Race: not indicated Location: Finland |

195 | Calcium + vitamin D | Calcium | Placebo | |

| DXA | ||||||||

| Total body BMC (%) | 34.7 | 35.0 | 35.0 | |||||

| Femoral neck BMC (%) | 24.0 | 23.3 | 22.4 | |||||

| Total femur BMC (%) | 33.6 | 36.4 | 33.6 | |||||

| pQCT | ||||||||

| Radius CSA | 23.0 | 26.0 | 21.3 | |||||

| Radius BMC | 22.6 | 24.4 | 22.2 | |||||

| Tibial CSA | 15.6 | 15.8 | 14.8 | |||||

| Tibial BMC | 23.0 | 24.3 | 22.7 | |||||

| No significant differences | ||||||||

| Fortified foods | ||||||||

| Calcium citrate-malate, 792 mg/day dissolved in a fruit drink | Lambert et al. 2008 [165] | 18-month randomized trial with follow-up 2 years after supplement withdrawal Low calcium intake at baseline (mean 636 mg/day) Differences in gain no longer apparent 2 years after supplement withdrawal |

Sex: 96 girls Age: 11–12 years Race: white Location: Sheffield, UK |

96 | Calcium supplement | Placebo | ||

| Total body BMC (g) | 1698 ± 14a | 1667 ± 14 | ||||||

| Lumbar spine BMC | 43.0 ± 0.6a | 41.1 ± 0.6 | ||||||

| Total hip BMC | 27.7 ± 0.3 | 27.2 ± 0.4 | ||||||

| Adjusted for baseline values, age at menarche, and age at menarche × visit interaction | ||||||||

| Calcium-enriched beverage, 1200 mg/day | Gibbons et al. 2004 [166] | 18-month placebo-controlled, double-blind RCT of a high-calcium beverage. Controls received 400 mg/day Baseline calcium intake: 934, supplement; 985, placebo 12-month additional follow-up after end of intervention |

Sex: male and female Age: 8–10 years Race: NZ European or Pakeha Location: New Zealand |

154 | Treatment | Control | ||

| Total body BMD | 4.4 % | 3.3 % (NS) | ||||||

| Hip BMD | 4.8 % | 3.9 % (NS) | ||||||

| Spine BMD | 5.9 % | 5.8 % (NS) | ||||||

| Trochanter BMD | 6.2 % | 5.1 % (NS) | ||||||

| Femoral neck BMD | 6.7 % | 7.0 % (NS) | ||||||

| Calcium-fortified foods, 850 mg/day | Chevalley et al. 2005 [168] | 1-year double-blind RCT of calcium-fortified foods (850 mg/day) compared to an isocaloric control | Sex: male Age: 6.5–8.5 years Race: white Location: Switzerland |

235 | Spine BMD (L2–4) Femoral diaphysis BMD Femoral neck BMD Trochanter BMD Radius BMD |

No difference in gain 19 % greater increase in trt (P < 0.006) 3 % lesser increase (NS) 22 % greater (NS) 15 % greater (NS) |

||

| 600 mg calcium in 375 mL soymilk | Ho et al. 2005 [167] | 1-year follow-up study between 104 adolescent girls receiving the fortified food and 95 girls in the control group | Sex: female Age: 14–16 years Race: Chinese Location: Hong Kong, China |

210 | Mean % change treatment ± SD | Mean % change, control | ||

| Neck of the femur BMD | 2.7 ± 2.94 | 1.8 ± 3.49 | ||||||

| Trochanter BMD | 3.3 ± 3.27a | 1.6 ± 2.94 | ||||||

| Intertrochanter BMD | 3.6 ± 3.05a | 2.32 ± 2.95 | ||||||

| Total hip BMD | 3.1 ± 2.39a | 2.05 ± 2.22 | ||||||

| Total hip BMC | 3.8 ± 3.05a | 2.6 ± 2.96 | ||||||

| Dairy foods | ||||||||

| Dairy foods, 1000 mg/day | Merrilees et al. 2000 [169] | 2-year RCT of dairy foods Baseline calcium: 744, supplement; 765, control 1 year after end of supplementation, differences no longer seen |

Sex: female Age: 15–17 years Race: unspecified NZ Location: New Zealand |

91 | Spine BMD Trochanter BMD Femoral neck BMD |

1.5 % greater increase in trt (P < 0.05) 4.6 % greater increase in trt 4.8 % greater increase in trt |

||

| 330 mL UHT milk (560 mg calcium), 330 mL UHT milk + 200 or 320 IU vitamin D3, or control | Du et al. 2004 [170] | 2-year school-based randomized trial | Sex: female Age: 10–12 years Race: Chinese Location: Beijing, China |

757 | Total body BMC Bone area |

35.9 % (P = 0.03) 31.3 % greater increase in trt (P = 0.2) |

||

95 % CI 95 % confidence interval, BMC bone mineral content, BMD bone mineral density, CSA cross-sectional area, NS not significant, pQCT peripheral quantitative computed tomography, RCT randomized controlled trial, SSI stress–strain index, trt treatment, UHT ultra-heat-treated, vBMD volumetric bone mineral density

aSignificantly greater than the control

Table 5.

Calcium and exercise and bone health in children and adolescents

| Reference | Study description | Population description | Number of subjects | End points | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molgaard et al. 2001 [245] | 1-year prospective observational study to determine effects of dietary calcium and physical activity on bone changes. | Sex: 140 boys, 192 girls Age: 5–19 years at baseline Race: Caucasian Location: Copenhagen, Denmark |

332 | Correlation with calcium intake, r | Correlation with physical activity, r | |

| Whole bone area gain adjusted for height and weight | 0.03, girls | 0.28 | ||||

| −0.34, boys | 0.28 | |||||

| Total body BMC gain adjusted for bone area, height, and weight | 0.21, girls | −0.06 | ||||

| 0.34, boys | −0.04 | |||||

| Carter et al. 2001 [171] | Cross-sectional study to investigate the relationship between calcium intake and BMC. | Sex: 108 boys and 119 girls Mean age: 13 years Race: Primarily Caucasian Location: Saskatoon Canada |

227 | Total body BMC | No association | |

| Lumbar spine BMC | No association | |||||

| Lloyd et al. 2000 [174] | 6-year prospective study to determine effects of dietary calcium and physical activity on bone changes | Sex: girls Age: 12–18 years at baseline Race: Caucasian Location: Pennsylvania |

81 | Total body BMC gain | NS | |

| Total body BMD gain | NS | |||||

| Femoral neck BMDa | r = 0.42 with exercise | |||||

| Lappe et al. 2014 [172] | 6-year prospective study of calcium intake and physical activity on bone accrual | Sex: boys and girls Age: 5–16 years at baseline Race: white, black, Asian, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Location: 5 sites in the USA |

1743 | Mixed-model analyses | ||

| Total body BMC gaina | Associated with physical activity in nonblacks | |||||

| Spine BMC gaina | Associated with physical activity in blacks and nonblack males | |||||

| Total hip BMC gaina | Associated with calcium in nonblack females | |||||

| Adjusted for changes in height, age, and baseline BMC | Associated with physical activity in nonblacks and black males | |||||

BMC bone mineral content, BMD bone mineral density, NS not significant

aSignificantly greater than the control

Table 6.

Vitamin D and bone health in children and adolescents

| Reference | Study description | Population description | Number of subjects | Primary end points | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | |||||||||

| Du et al. 2004 [170] | This study was a 2-year milk intervention trial in girls from nine primary schools in Beijing. Schools were randomized into three groups: (1) a carton of 330-mL milk fortified with calcium per school day, (2) a carton of 330-mL milk fortified with 200 or 320 IU 8 mg vitamin D3, and (3) control | Sex: female Age: 10–12 years Race: Asian (Chinese) Location: Beijing, China Year(s): 1999–2001 Baseline 25(OH)D as mean (SD) in nmol/L: Control: 19.1 (7.4) Calcium only: 17.7 (8.7) Calcium + vitamin D: 20.6 (8.8) |

757 | Data are shown for a subsample with bone measures (N = 346) | Percent change | P | |||

| Milk with calcium (n = 111) | Milk with calcium + vitamin D (n = 113) | Control (n = 122) | |||||||

| Total body | |||||||||

| Bone area | 29.5 | 28.5 | 31.3 | NS | |||||

| BMC | 38.4 | 39.7 | 35.9 | <0.01 | |||||

| Percent change, calcium + vitamin D, minus calcium | P | Percent change, calcium + vitamin D, minus control | P | ||||||

| Total body | |||||||||

| Bone area | 0.8 | NS | −1.8 | 0.04 | |||||

| BMC | −0.8 | NS | 2.6 | <0.01 | |||||

| Size-adjusted BMC | 1.3 | <0.01 | 2.4 | <0.01 | |||||

| • Mean percent change values in the calcium + vitamin D group were significantly different from controls. • Adjusted percentage difference in change values are adjusted for baseline. • Size-adjusted BMC is adjusted for baseline BMC, bone area, height, weight, and menstrual status. | |||||||||

| Cheng et al. 2005 [159] | The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of both food-based and pill supplements of calcium and vitamin D3 on bone mass and body composition. Children were randomized into four groups: (1) 1000 mg calcium + 200 IU vitamin D3, (2) 1000 mg calcium + vitamin D3 placebo, (3) 1000 mg calcium from dairy products,and (4) calcium + vitamin D3 placebo for 2 years | Sex: female Age: 10–12 years Race: Finnish, otherwise unspecified Location: Jyvaskyla and surrounding cities in Central Finland Year(s): Unspecified Baseline 25(OH)D as mean (95 % CI): 45.9 (43.8, 48.0) nmol/L |

195 | Data are shown for the overall group who started the intervention (N = 181) | Percent change | P | |||

| Calcium (n = 41) | Calcium + vitamin D3 (n = 46) | Cheese (n = 39) | Placebo (n = 39) | ||||||

| Lumbar spine | |||||||||

| Bone area | 28.4 | 23.0 | 25.3 | 23.4 | NS | ||||

| BMC | 24.0 | 46.9 | 52.4 | 47.0 | NS | ||||

| Total hip | |||||||||

| Bone area | 24.1 | 17.0 | 18.1 | 17.3 | NS | ||||

| BMC | 20.3 | 33.6 | 36.9 | 33.6 | NS | ||||

| Femoral neck | |||||||||

| Bone area | 3.8 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 15.0 | NS | ||||

| BMC | 3.3 | 24.0 | 26.5 | 22.4 | NS | ||||