Abstract

Rhythmic movements are ubiquitous in animal locomotion, feeding, and circulatory systems. In some systems, the muscle itself generates rhythmic contractions. In others, rhythms are generated by the nervous system or by interactions between the nervous system and muscles. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, feeding occurs via rhythmic contractions (pumping) of the pharynx, a neuromuscular feeding organ. Here, we use pharmacology, optogenetics, genetics, and electrophysiology to investigate the roles of the nervous system and muscle in generating pharyngeal pumping. Hyperpolarization of the nervous system using a histamine-gated chloride channel abolishes pumping, and optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle in these animals causes abnormal contractions, demonstrating that normal pumping requires nervous system function. In mutants that pump slowly due to defective nervous system function, tonic muscle stimulation causes rapid pumping, suggesting tonic neurotransmitter release may regulate pumping. However, tonic cholinergic motor neuron stimulation, but not tonic muscle stimulation, triggers pumps that electrophysiologically resemble typical rapid pumps. This suggests that pharyngeal cholinergic motor neurons are normally rhythmically, and not tonically active. These results demonstrate that the pharynx generates a myogenic rhythm in the presence of tonically released acetylcholine, and suggest that the pharyngeal nervous system entrains contraction rate and timing through phasic neurotransmitter release.

Rhythmic muscle contractions are required for many aspects of physiology and behavior, from circulation to locomotion1. These rhythms can be described as myogenic, if intrinsic oscillations of membrane currents in the muscles drive contractions, or neurogenic, if a network of neurons acts as a central pattern generator (CPG) to drive muscle contraction. For example, vertebrate heart muscle generates its own rhythms. The autonomic nervous system modulates the rate and strength of cardiac contraction but does not provide any beat-to-beat timing information2, and innervation of the heart is dispensable for coordinated and effective cardiac function3. In contrast, a neural circuit in the vertebrate spinal cord controls locomotion by acting as a neural pacemaker, producing patterned activity that drives contraction of passively responding skeletal muscles4.

Myogenic and neurogenic rhythms are not mutually exclusive: in some systems both the nervous system and muscles are capable of generating rhythms independently, and interact to generate rhythmic behavior. For example, leech heart motor neurons display rhythmic activity and entrain the myogenic rhythmic contractions of the heart5. Similarly, the crustacean pyloric dilator muscle exhibits a myogenic rhythm that is entrained by rhythmic activity in the stomatogastric neural system6. By contrast, mollusc heart motor neurons modulate heart rate over long time scales without entraining the heartbeat7.

The mechanisms that underlie rhythmic behaviors have been most studied in invertebrates such as leeches, crustaceans, and molluscs due to the small number of neurons and relative ease of electrophysiological recordings in these animals. The ability to electrophysiologically identify the functional synaptic connectivity between neurons in these systems has enabled researchers to determine the roles of intrinsic and synaptic properties of individual neurons and muscles in generating rhythmic behaviors1,8,9. However, these organisms are not amenable to genetic approaches, limiting their utility for investigation of the genetic and molecular bases of rhythm generation in nervous systems and muscles.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans represents a unique and powerful model for elucidating the genetic, neural, and muscular bases of behavior10,11. Among its strengths are its compact, extraordinarily well-mapped nervous system12,13, genetic manipulability, and optical transparency. The development of optical14,15 and electrophysiological16 methods for manipulating and monitoring neural activity has begun to enable analysis of the physiology and functional connectivity of C. elegans neural circuits. Such investigations apply a conceptual approach similar to that developed in leeches, crustaceans, and gastropods while leveraging the extensive genetic toolkit available in worms. Thus, C. elegans is well suited to provide insights into mechanisms that underlie rhythmic behaviors.

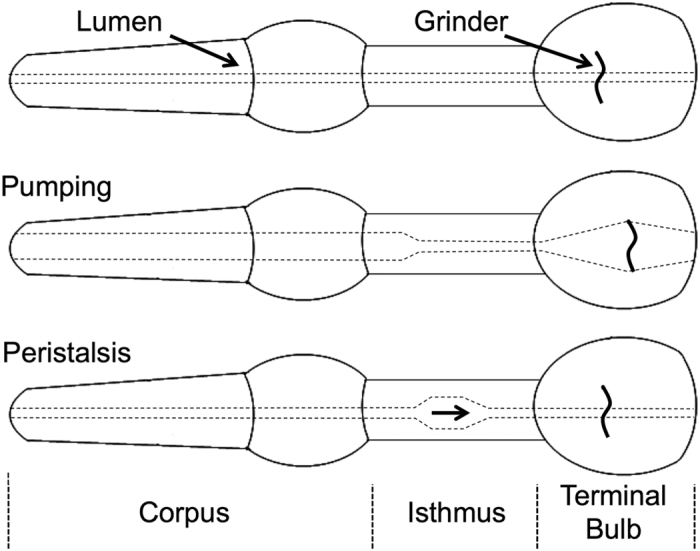

C. elegans feeds on bacterial food via rhythmic contractions and relaxations of its pharynx (Fig. 1), a neuromuscular pump with similarities to the vertebrate and invertebrate heart. Like these hearts, the pharynx is a tube of electrically coupled muscle cells17,18,19,20 that pumps throughout the life of the animal. It responds to a variety of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators21, and relies on T- and L-type Ca2+ channels for its action potential22,23. The pharynx possesses a nervous system, a network of 20 neurons of 14 types, that is largely independent of the extra-pharyngeal nervous system and accounts for all chemical synapses onto pharyngeal muscle13.

Figure 1. The pharynx consists of three functional units, the corpus, isthmus, and terminal bulb.

During a pump, food enters via the corpus. It is then transferred along the isthmus via posteriorly propagating peristaltic waves before being broken up by the cuticular grinder in the terminal bulb during the subsequent pump. Anterior is left.

The role of the pharyngeal nervous system in the generation of rhythmic pharyngeal behavior is not yet clear. Laser ablation of all pharyngeal neurons does not completely abolish pharyngeal pumping24, nor does optogenetic hyperpolarization of all cholinergic pharyngeal motor neurons25,26, which normally excite pumping24,25,27. On the basis of these findings, the pharyngeal pumping rhythm has been described as myogenic24,28. However, pumping is abolished by genetic manipulations that eliminate cholinergic synaptic transmission29,30 or all synaptic transmission31,32,33, indicating that some nervous system function is required for pumping.

Of the 20 pharyngeal neurons, the two cholinergic MC motor neurons appear to be the most important for regulation of rapid pumping: MC ablation dramatically decreases pump rate24,27, and optogenetic stimulation or inhibition of the MC neurons increases or decreases pump rate, respectively25. The MC neurons are activated by serotonin (5-HT)34 and appear to act primarily via a nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptor containing the non-α subunit EAT-2, as eat-2 mutants resemble MC-ablated animals25,27,35,36. Electropharyngeograms (EPGs), extracellular recordings of pharyngeal muscle electrical activity37, reveal a very brief MC- and EAT-2-dependent depolarization preceding each muscle action potential during rapid pumping27. This depolarization may represent a response to pulsed neurotransmitter release from the MC neurons, but this idea is challenging to test since the activity patterns of the MC neurons are unknown and currently difficult to measure.

We explored how the nervous system and pharyngeal muscle interact to control pumping, with the goal of comparing the mechanisms of pharyngeal contraction generation with those found in vertebrate and invertebrate hearts and other rhythmic systems. Our results demonstrate that the pharyngeal muscle generates a myogenic rhythm only in the presence of tonically released ACh, and suggest that the MC neurons stimulate pumping by rhythmically exciting and entraining the pharyngeal muscle rhythm in a manner similar to that by which the leech heartbeat is controlled by heart motor neurons.

Results

Pharyngeal pumping acutely requires nervous system function

The finding that pharyngeal pumping persists after laser ablation of the entire pharyngeal nervous system24 or after hyperpolarization of excitatory pharyngeal cholinergic neurons25,26, yet is abolished in mutants lacking ACh release29,30,31,32,33 suggests that ACh from the extra-pharyngeal nervous system is sufficient to induce feeding. However, since severe synaptic transmission mutations cause chronic changes in animal physiology and development, it is possible that the lack of feeding observed in these mutants may be explained by developmental abnormalities.

To test the role of the nervous system in pumping while avoiding the confounding issue of abnormal development in mutant backgrounds, we sought to determine if the nervous system is acutely required for pumping. In order to acutely silence the nervous system, we expressed a histamine-gated chloride channel (HisCl) in all neurons using the Ptag-168 promoter38. HisCl activation has been shown to silence neurons in every case tested, both in C. elegans38,39 and in Drosophila40. Therefore, in worms expressing pan-neuronal HisCl, exogenous histamine is expected to lead to hyperpolarization of both pharyngeal and extra-pharyngeal neurons38, including excitatory cholinergic pharyngeal neurons such as the MCs. After 15 minutes on a 2% agarose pad containing 10 mM histamine, pumping completely ceased in worms expressing pan-neuronal HisCl (n > 80), while pumping persists on 2% agarose pads in worms lacking pan-neuronal HisCl41. Exposure of these worms to histamine does not dramatically affect pumping, as worms raised on histamine do not show severe growth defects38,39. Therefore, unlike the vertebrate, leech, and mollusc hearts, the pharynx requires a signal from the nervous system to produce myogenic contractions. Since ablation of the pharyngeal nervous system does not abolish pumping24, it appears that this signal can come from the extra-pharyngeal nervous system. However, since extra-pharyngeal neurons do not synapse on pharyngeal muscle, they cannot provide pump-to-pump timing information.

Normal pharyngeal muscle coordination requires the nervous system

We sought to better understand the role of the pharyngeal nervous system in coordinating pharyngeal pumps. The pharynx can be divided into three functional units13 (Fig. 1). The anterior end of the pharynx contains the corpus, which draws in the bacterial food during muscle contraction. The posterior end of the pharynx contains the terminal bulb, which houses the grinder, three cuticular plates that crush the bacteria so their contents can be absorbed by the intestine. The isthmus connects the corpus and terminal bulb. Pharyngeal muscle fibers are oriented radially, so muscle contraction opens the lumen and relaxation closes it. During pumping, it is necessary for different parts of the pharynx to contract with slightly different timing to effectively transport food to the intestine42. A pharyngeal pump begins with the nearly simultaneous contraction of the corpus and the terminal bulb, drawing food particles into the pharyngeal lumen, followed by contraction of the anterior isthmus. After approximately 200 ms, these muscles begin to relax. The anterior tip of the corpus relaxes first, preventing food particles from escaping when the rest of the muscles relax43. Likewise, the corpus relaxes before the isthmus, allowing bacteria to be trapped in the anterior isthmus43,44. Posteriorly-propagating contractions of the posterior isthmus, known as peristalsis, transport bacteria from the anterior isthmus to the terminal bulb after about one out of every four pumps45.

To gain insight into which aspects of pharyngeal pumping require the nervous system, we sought to determine the extent to which direct stimulation of pharyngeal muscle in the absence of nervous system function recapitulates normal muscle contraction patterns. In the absence of neural input, the vertebrate heart generates motions that are essentially the same as those observed with neural input; neural input modulates only the rate and force of cardiac contractions2. In contrast, in the leech heart, the electrical activity of the muscle is altered when the nervous system is hyperpolarized5. To test whether the pharynx produces motions in the absence of neural input that are similar to those produced in the presence of neural input, we silenced the nervous system using pan-neuronal HisCl activation and then stimulated the muscle directly using the light-activated excitatory opsin Chrimson expressed in pharyngeal muscle46. We used high-speed video recordings to examine the muscle contraction patterns of these worms in response to 200 ms optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle in the presence of histamine.

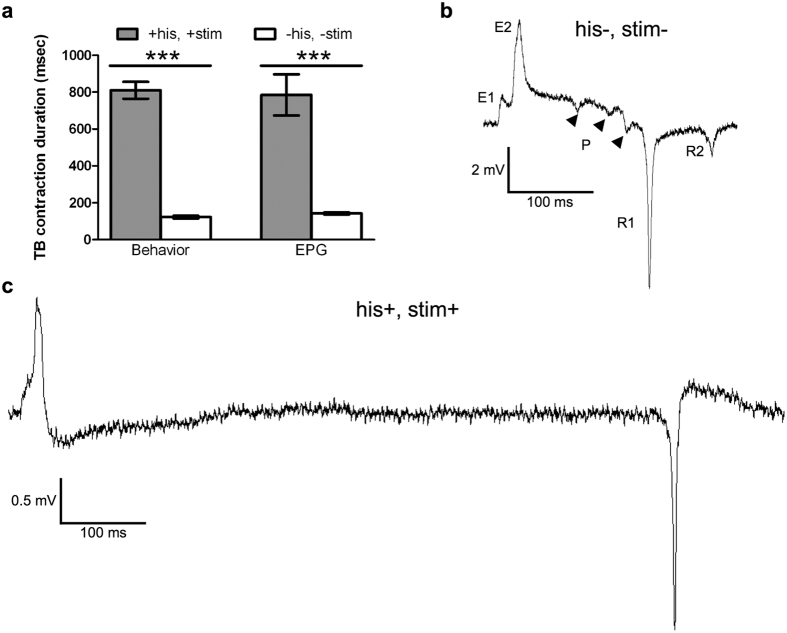

We compared pan-neuronally hyperpolarized animals with muscle optogenetic stimulation to animals of the same strain without histamine or muscle stimulation, and we found two striking differences. First, in 31/37 experimental worms, we observed contraction in the terminal bulb but not in the corpus in response to optogenetic stimulation. The remaining 6/37 experimental worms showed feeble corpus contractions. By contrast, in the absence of histamine and optogenetic muscle stimulation, all worms of this strain had normal contractions of the corpus in addition to the terminal bulb (N = 15). The difference between the experimental and control worms is statistically significant (p < 0.05, Z test). The other striking difference was that the duration of terminal bulb contraction in the presence of histamine and optogenetic muscle stimulation was 805 ± 52 ms, (mean ± SEM, Fig. 2a), far exceeding the 200 ms stimulus duration. These data suggest that pharyngeal muscle contractions are defective in the acute absence of nervous system function, demonstrating that the nervous system plays a role in setting contraction duration and pattern.

Figure 2. The nervous system modulates terminal bulb contraction rate.

(a) 200 ms optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle in worms expressing pan-neuronal HisCl and in the presence of histamine caused pumps with long terminal bulb contractions as measured by either high-speed video recordings of muscle contractions (behavior) or electrophysiological recordings (EPG). For video analysis, N = 15 worms for light−, his−, N = 37 worms for light+, his+. For EPG analysis, N = 11 for light−, his−, N = 15 for light+, his+. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ***p < 0.001. (b) Example EPG trace for his-, light- worm. The various components of the EPG are labeled. Arrowheads indicate P spikes. (c) Example EPG trace for his+, light+ worm.

Three classes of mutants have been identified with increased pump duration24. Mutants defective in the neurotransmission of the M3 glutamatergic inhibitory motor neurons, including those lacking the vesicular glutamate transporter gene eat-447 or the avermectin-sensitive glutamate-gated Cl− channel gene avr-1548, have prolonged contractions due to lengthened pharyngeal action potentials. Prolonged contractions due to long actions potentials are also seen in mutants with increased pharyngeal excitability, including loss-of-function mutations in the Na+/K+ transporter α-subunit gene eat-649 or the K+ channel gene exp-250, or gain-of-function mutations in the L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit gene egl-1926,47. In contrast, worms with increased Gαq signaling due to mutations in the RGS protein eat-16 or the Gβ5 subunit gene gbp-2, or overexpression of muscarinic ACh receptor gene gar-3, show muscle contractions that outlast pharyngeal action potentials51,52. Thus, multiple mechanisms could explain the long contractions observed when the nervous system is silenced and the muscle is optogenetically stimulated.

To differentiate between these mechanisms, we recorded EPGs. During a pharyngeal pump, the EPG shows two prominent features arising from muscle activity: an E2 spike that indicates muscle depolarization, and the R1 and R2 spikes that represent repolarization of the corpus and terminal bulb muscles, respectively (Fig. 2b). P spikes represent inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) evoked by the M3 neurons during the pump37,42,48. When we stimulated the pharyngeal muscle in worms in which the nervous system was silenced via the HisCl channel, we found that pharyngeal muscle action potential duration, measured as the time between the E2 and R1 spikes, was dramatically increased (Fig. 2a,c), suggesting that increased pump duration is due to either decreased M3 activity or altered pharyngeal excitability. However, while we noted that P spikes were absent in these worms, the prolongation of the pumps we observed was far more extreme than that found in animals lacking M3 neurotransmission42 or even in animals lacking all pharyngeal neurons24. This suggests that the nervous system promotes terminal bulb relaxation by altering the membrane or ion channel properties or Ca2+ signaling in the pharyngeal muscle.

Tonic depolarization of pharyngeal muscle can stimulate rapid pumping in mutants with defective neurotransmission

Having established that normal myogenic pharyngeal muscle contraction requires nervous system activity but not precise timing information, we next sought to determine if the nervous system provides phasic input to regulate rapid pumping, as in the leech heartbeat, or modulatory input that regulates the myogenic contraction rate, as in vertebrate and mollusc hearts. Recent reports have shown that both phasic and tonic optogenetic excitation of pharyngeal muscle can stimulate rapid pumping26,46. However, the role of the nervous system in this rapid pumping is unclear.

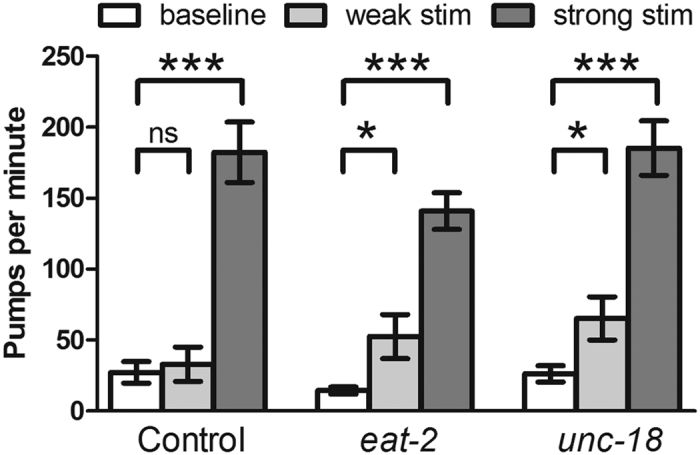

To test if rapid, phasic excitation from the MC or other neurons is essential for rapid pumping, we measured the pumping rate during tonic optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle in two mutants with defective neurotransmission. In worms with normal MC neurons and the EAT-2-containing receptor, EPG recordings in the presence of 5-HT reveal that each pharyngeal muscle action potential is preceded by a small depolarization resembling an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) (the E1 spike in Fig. 2b)27, and absence of MC or EAT-2 causes a dramatic decrease in pump rate and the disappearance of the E1 spike24,35. To test if MC function via the EAT-2-containing receptor is required for rapid pumping in the presence of 5-HT, we optogenetically stimulated the pharyngeal muscle in eat-2 mutants. Whereas optogenetic stimulation of the MC neurons in these mutants in the presence of 5-HT caused only a small increase in pumping25, we found that tonic optogenetic pharyngeal muscle stimulation under similar conditions caused a dramatic increase in pump rate similar to that seen in control worms (Fig. 3), demonstrating that rapid pumping can occur in the absence of nicotinic MC neurotransmission.

Figure 3. Tonic optogenetic muscle stimulation causes rapid pumping in mutants with defects in excitatory transmission.

Strong optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle produced similar pumping rates in control worms, eat-2 mutants, and unc-18 mutants, while weak optogenetic stimulation excited pumping in eat-2 and unc-18 mutants but not control worms. For control worms, we selected worms with low basal pumping rates so the data would be more comparable to that of eat-2 and unc-18 mutants. N = 8–10 worms. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Next, to test whether direct muscle stimulation can trigger rapid pumping even when neurotransmission is severely and globally impaired (but not abolished), we repeated this experiment in the strongest viable synaptic null mutant available, unc-1853. Null mutants for syntaxin (unc-64)31, SNAP-25 (ric-4)54, synaptobrevin (snb-1)32, and unc-1333 are not viable, indicating that complete absence of synaptic release is lethal. Thus, since unc-18 null mutants are sick and slow growing but viable, we reasoned that these mutants have sufficient nervous system function to permit myogenic pumping, but not enough to stimulate rapid pumping, hence their decreased basal pump rate. A recent report found that pumping could be triggered by rhythmically depolarizing pharyngeal muscle in an unc-13 partial loss of function mutant, though only to a rate similar to that of unstimulated unc-13 mutants and at least five-fold slower than the rate observed in wild-type animals26.

As with eat-2 mutants, optogenetic muscle stimulation in unc-18 mutants caused rapid pumping at a rate similar to that of control worms (Fig. 3), much faster than that normally observed in these mutants53, demonstrating that rhythmic input from the nervous system is not required for rapid pumping. When subjected to a milder optogenetic stimulus, eat-2 and unc-18 mutants but not control worms showed an increase in pumping rate (Fig. 3), suggesting an activity-dependent homeostatic increase in membrane excitability may occur in these mutants55. This is supported by evidence that in eat-2 mutants, the resting membrane potential is depolarized and unstable56. Together, these results show that tonic depolarization of pharyngeal muscle is sufficient to trigger rapid pumping even when the excitatory inputs to the pharynx are defective.

Tonic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle and tonic stimulation of cholinergic neurons yield distinct electrical activity patterns

Both tonic and phasic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle are individually sufficient to drive rapid pumping at physiological rates26,46. Therefore, it is unclear whether MC activity during normal rapid pumping is rhythmic or tonic. On one hand, EPG recordings reveal EAT-2-dependent depolarizations in pharyngeal muscle preceding each muscle action potential during rapid pumping in the presence of 5-HT (the E1 spike in Fig. 2b). These spikes have been hypothesized to represent EPSPs from rhythmic MC action potentials, which entrain the pharyngeal muscles27. On the other hand, since these depolarizations are observed during rapid pumping but not slow pumping27, and rapid neurotransmission from MC is not essential for rapid pumping (Fig. 3), the E1 spikes may be a consequence of rapid pumping that do not reflect nervous system activity, leaving open the possibility that MC may act tonically.

To explore the nature of MC signaling, we examined EPGs during optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscles and neurons. The MC neuron cell bodies are small (2–3 μm in diameter16) and are embedded in the pharyngeal muscle, which is surrounded by a thick basement membrane. As a result, electrical recording from these neurons is not currently possible. The most direct way to determine the activity pattern of these neurons would be with fluorescent calcium indicators, however GCaMP6s is not sufficiently fast to use at pumping rates near 4 Hz57, and we were unable to achieve adequate expression levels of the faster GCaMP6 variants.

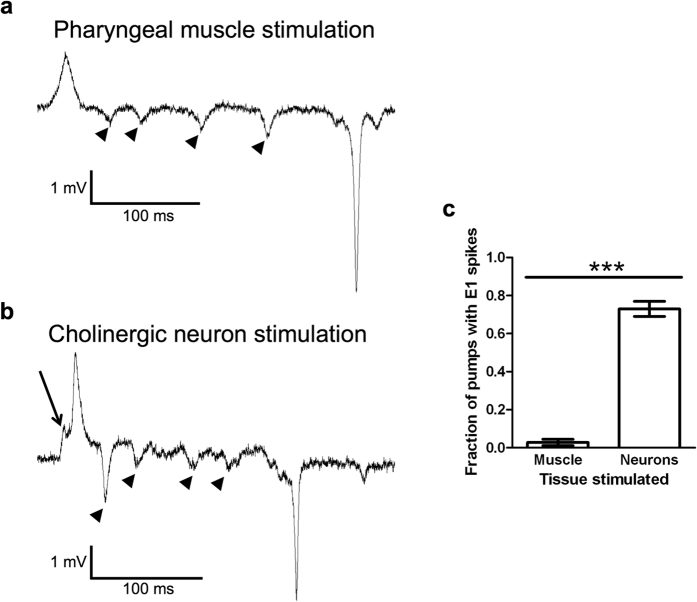

To determine if the E1 spike is a consequence of rapid pumping or represents an EPSP from MC, we recorded the electrical activity of the pharyngeal muscle during tonic optogenetic stimulation of the muscle in the presence of 5-HT. We found that when we stimulated the muscle to evoke rapid pumping, the E1 spike was absent from nearly all pumps (Fig. 4a,c). This result demonstrates that E1 spikes are not artifacts of rapid pumping. If MC stimulates pumping by tonic release of ACh, we would expect that tonic MC stimulation causes similar electrical activity to that seen during tonic muscle stimulation. In contrast, we found that during optogenetic stimulation of the cholinergic neurons, including the MC neurons, most pumps contained an E1 spike (Fig. 4b,c). EPG recordings during direct pharyngeal muscle stimulation contained P spikes (see arrow heads in Fig. 4a), which reflect the activity of the inhibitory glutamatergic M3 motor neurons37. The presence of these spikes suggests that M3 activity is directly triggered by muscle contraction in the absence of neural excitatory activity. Hence, as previously proposed37, M3 likely has a proprioceptive sensory function in addition to its motor neuron function.

Figure 4. E1 spikes are detected after cholinergic neuron but not muscle stimulation.

(a) Example EPG trace during tonic muscle stimulation. (b) Example EPG trace during tonic neuron stimulation. The arrow is pointing to the E1 spike, seen during tonic neuron stimulation but not tonic muscle stimulation. Arrowheads in A and B indicate P spikes due to M3 activity. (c) EPG recordings during optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic neurons but not pharyngeal muscle reveal E1 spikes during most pumps. We stimulated each worm 3 times for 5 seconds each time, then for each worm counted the fraction of pumps that had E1 spikes. N = 12 worms. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ***p < 0.001.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that tonic optogenetic depolarization of the muscle stimulates pumping by increasing the rate of the myogenic rhythm, while tonic MC stimulation increases the rate of the neurogenic rhythm, suggesting that the MC neurons are rhythmically rather than tonically active (Table. 1). Thus, the pharyngeal nervous system seems to regulate pumping by a mechanism similar to that of the leech heartbeat, in which the motor neurons entrain muscle contraction rate via temporally patterned input, as opposed to the mechanism controlling the vertebrate or mollusc heartbeat, where the nervous system provides modulatory input to regulate contraction rate.

Table 1. Summary of key results in this paper and other relevant results25,27,46.

| Presence of 5-HT |

Tonic neuron stimulation |

Tonic muscle stimulation |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS intact | NS defective | NS intact | NS defective | NS intact | NS defective | |||||||

| Pump rate | Rapid | Ref. 27 | Slow | Ref. 27 | Rapid | Ref. 25 | Slow | Ref. 25 | Rapid | Ref. 46 | Rapid | Fig. 3 |

| E1 spikes | Yes | Ref. 27 | No | Ref. 27 | Yes | Fig. 4B | Not Tested | No | Fig. 4A | Not Tested | ||

References or figures for each observation are listed in the table. Tonic optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal neurons causes rapid pumping with E1 spikes, representing activation of the neurogenic rhythm and mimicking rapid pumping in the presence of food. In contrast, tonic optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle causes rapid pumping without E1 spikes, representing activation of the myogenic rhythm and mimicking pumping seen in mutants with defective (but not abolished) rhythmic nervous system input onto pharyngeal muscle, such as eat-2 mutants. In these mutants, activation of the myogenic but not neurogenic rhythm increases pumping rate, as expected.

Discussion

A model for control of pumping rate

In this work, we sought to investigate the roles of the nervous system and pharyngeal muscle in the generation of rhythmic pharyngeal pumping. Our results support a model in which the presence of tonically released ACh alters the intrinsic properties of pharyngeal muscles so that contraction and relaxation are fast enough to permit rapid and effective pumping, establishing a myogenic rhythm (Fig. 5). Alternatively, it is possible that subthreshold myogenic oscillations occur in the pharyngeal muscle, and ACh is required to allow these oscillations to produce muscle contraction. In either case, it is possible that this ACh normally comes from the pharyngeal nervous system, as the sufficiency of the extra-pharyngeal nervous system for this function is only revealed when the pharyngeal nervous system is absent. Indeed, pumping persists when the pharyngeal nervous system and muscle are dissected away from the rest of the body in the presence of 5-HT, which stimulates the MC neurons27,34.

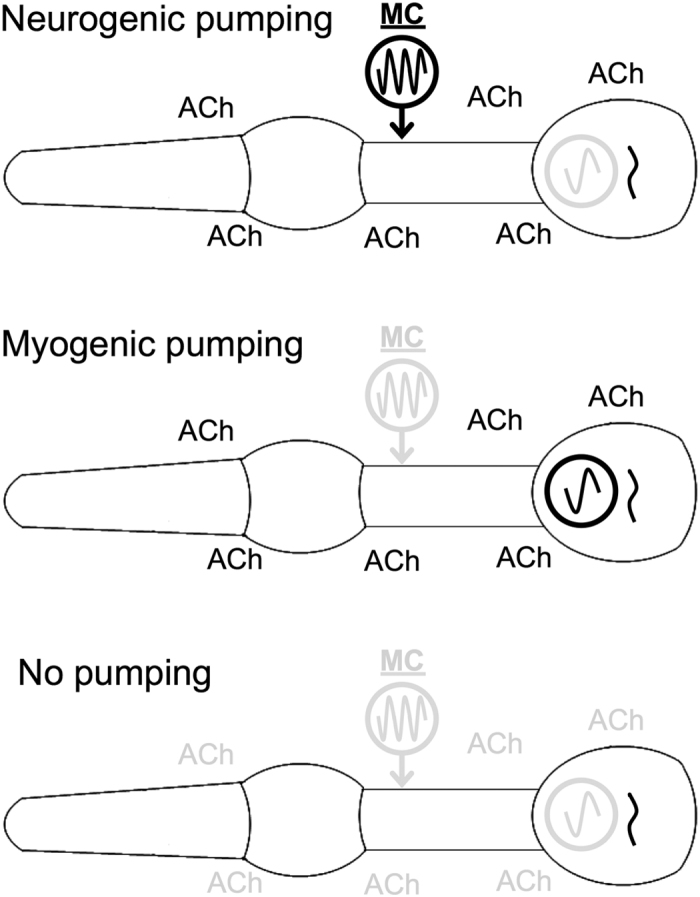

Figure 5. Model representing hypothesized myogenic and neurogenic mechanisms for pumping control.

In intact worms, the activity of the MC neurons entrains the pharyngeal muscle and overrides the myogenic rhythm to cause rapid neurogenic pumping. When MC activity or postsynaptic response to MC activity is decreased, the myogenic rhythm sets the pumping rate. In the acute absence of nervous system function, pumping ceases completely. ACh represents acetylcholine. Circles with enclosed waveforms represent oscillators. Elements in gray are inactive.

Our results also support a model in which the cholinergic pharyngeal neurons, primarily the MC neurons, control pumping via rhythmic activity (Fig. 5). Previous reports have shown that either tonic or phasic stimulation of pharyngeal muscle is sufficient for driving rapid pumping26,46, and that tonic stimulation of pharyngeal neurons can stimulate rapid pumping25. Our EPGs reveal that tonic muscle stimulation induces rapid pumping but does not recapitulate the pattern of electrical activity seen during 5-HT-stimulated pumping, which requires the MC neurons27. This result suggests that tonic muscle stimulation increases the rate of the myogenic rhythm rather than mimicking neural activity.

Our EPG recordings indicate that although MC is not active during pumping induced by optogenetic muscle stimulation, M3 is active (Fig. 4a). Taken together with previous work, this finding suggests that M3 fires action potentials in response to pharyngeal muscles contraction37. The resulting IPSPs shorten the duration of muscle contraction and contribute to effective food transport37,42,48. This proprioceptive feedback demonstrates an additional layer of complexity in the pharyngeal circuit as it shows that some neurons can have both sensory and motor functions, a phenomenon previously described in a class of motor neurons that regulate C. elegans locomotion58. In the future, the combination of genetic manipulations and the monitoring of neuron and muscle activity with genetically encoded calcium or voltage sensors will provide more information about the activity of pharyngeal nervous system, permitting a better understanding of the function of this network59.

Why does the pharynx require the nervous system for pumping?

Muscular pacemakers such as the vertebrate, leech, and mollusc hearts contract rhythmically when isolated from their respective nervous systems, but the pharyngeal muscle requires an extrinsic factor to exhibit pumping. While the pharynx and vertebrate heart have many similar ionic conductances, one striking difference between them is that the C. elegans genome does not have any homologs of genes encoding HCN channels, which mediate the hyperpolarization-activated mixed cation current in the vertebrate heart referred to as the pacemaker current60. The absence of the so-called pacemaker current in the pharynx could explain why the pharynx does not spontaneously contract in the absence of extrinsic factors, as the membrane may not depolarize in response to hyperpolarization.

Recent evidence suggests that in addition to the well-characterized membrane oscillator in the vertebrate heart, a Ca2+ oscillator may act simultaneously and work with the membrane oscillator to mediate contraction2. The ryanodine receptor is critical for vertebrate heart function, but the gene encoding the C. elegans ryanodine receptor (unc-68) is relatively unimportant for pharyngeal function61, and there is no evidence of a corresponding Ca2+ oscillator in the pharynx. Additionally, while the K+ channel responsible for pharyngeal repolarization (EXP-2) has generally similar properties to the vertebrate HERG channel, it is structurally dissimilar50, suggesting that it may have subtle differences in function that affect the stability of the muscle membrane potential and its ability to generate rhythmic activity.

Multiple mechanisms for modulation of pumping rate

The results described here have implications for understanding how neuromodulators influence pumping rate. Many neuromodulators, including biogenic amines62 and neuropeptides63, are released from pharyngeal and extra-pharyngeal neurons64,65 and a subset of these stimulate or inhibit pumping. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that these modulators may act on either the pharyngeal neurons or muscles46,63. For example, the extra-pharyngeal nervous system could non-synaptically regulate pump rate by altering the myogenic rhythm, bypassing the pharyngeal nervous system, in a mechanism similar to that of vertebrate hearts, or by altering the neurogenic rhythm. The identification of two distinct pacemakers capable of producing rapid pumping suggests that there are many different mechanisms by which neuromodulators can influence pharyngeal pumping, even if their effects on behavior are similar25,46.

Materials and Methods

Worm strains and cultivation

We performed all experiments with adult hermaphrodites. Unless otherwise specified, animals were cultivated on the surface of NGM agar in a 20 °C incubator. Strains used include YX11 vsIs48[Punc-17::GFP] X; zxIs6[Punc-17::ChR2(H134R)::YFP; lin-15(+)]25, CX16557 kyIs5640[Pmyo-2::Chrimson; Pelt-2::his4.4-mCherry]46, YX87 eat-2(ad1113) II; kyIs5640[Pmyo-2::Chrimson; Pelt-2::his4.4-mCherry], YX97 unc-18(e81) X; kyIs5640[Pmyo-2::Chrimson; Pelt-2::his4.4-mCherry], CX14373 kyEx4571[Ptag-168::HisCl1::SL2::GFP; Pmyo-3::mCherry]38, and YX96 kyIs5640[Pmyo-2::Chrimson; Pelt-2::his4.4-mCherry]; kyEx4571[Ptag-168::HisCl1::SL2::GFP; Pmyo-3::mCherry].

Optogenetics

We performed optogenetic stimulation of pharyngeal neurons and muscles as previously described25,46,66. All experiments were performed on 10% agarose pads containing 10 mM serotonin (5-HT) mounted on glass slides, except experiments involving histamine, which were performed on a 2% agarose pad lacking 5-HT, and electrophysiological recordings, which were performed in Dent’s saline67 with 10 mM 5-HT. For experiments using weak optogenetic stimulation, we used a red LED with an irradiance of approximately 0.35 mW/mm2. For strong optogenetic stimulation, we used ~37 mW/mm2, as described previously25,46,66.

High speed imaging

We performed all high speed imaging experiments with the strain YX96 kyIs5640[Pmyo-2::Chrimson; Pelt-2::his4.4-mCherry]; kyEx4571[Ptag-168::HisCl1::SL2::GFP; Pmyo-3::mCherry] on 2% agarose pads in the presence of OP50 bacterial food. For control and experimental worms, we imaged pharyngeal behavior using an infrared LED (800–850 nm wavelength) placed directly above the condenser of a Leica DMI 3000B inverted microscope. This wavelength was selected to avoid stimulating Chrimson. We recorded behavior at 500 frames per second using a Vision Research Phantom v9.1 CMOS camera, then manually annotated pumping events with the help of custom MATLAB scripts. For the experimental group, we added 10 mM histamine to the agarose pads. We stimulated pumps using 200 ms pulses of the same red LED used for other weak optogenetic experiments. Since the pan-neuronal HisCl-containing transgene was present as an extrachromosomal array, expression patterns were variable between worms. We therefore reasoned that the worms with the most abnormal behavior were those with the broadest expression, and thus only analyzed recordings for worms in which the behavior was most abnormal, those in which 200 ms stimulation caused only a single pump. Subsequent experiments after integrating this transgene produced qualitatively similar results.

Electropharyngeograms

EPGs were performed as previously described37,67. We performed EPGs on intact first day adult worms. We created recording chamber by making a ring of vacuum grease on a cover slide, then filled the chamber with Dent’s saline67 containing 10 mM serotonin. 10–15 worms were added to the chamber for each experiment. Worms were then sucked into glass microelectrodes, which were connected by a silver chloride coated silver wire to an Axon Instruments CV-7B headstage. The headstage was connected to Axon Instruments MultiClamp 700B amplifier and DigiData 1440A digitizer. Electrodes were fabricated on a Sutter P-1000 micropipette puller using borosilicate glass with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. Electrodes were pulled to an inner diameter of approximately 20 μm. We performed optogenetic stimulation25,46,66, using 5 s light pulses separated by 5 s, with the exception of the experiments with worms expressing the pan-neuronal HisCl channel, where we used 200 ms light pulses. All recordings were performed in current clamp mode. E1 spikes were identified by manual observation of the EPG traces using the Axon Instruments pCLAMP 10 software package.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Trojanowski, N. F. et al. Pharyngeal pumping in Caenorhabditis elegans depends on tonic and phasic signaling from the nervous system. Sci. Rep. 6, 22940; doi: 10.1038/srep22940 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Cori Bargmann for sharing strain CX14373, and Brian Chow for loaning electrophysiology equipment. We thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. Some worm strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40OD010440). N.F.T. was supported by National Institutes of Health (T32HL007953). D.M.R. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS088432, and R21NS091500). C.F.-Y. was supported by an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship and the National Institutes of Health (R01NS084835 and R21NS091500).

Footnotes

Author Contributions N.F.T., D.M.R. and C.F.-Y. designed the research and wrote the paper; N.F.T. performed the research and analyzed the data.

References

- Selverston A. I. Invertebrate central pattern generator circuits. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365, 2329–2345 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni M. E. & Nargeot J. Genesis and Regulation of the Heart Automaticity. Physiol Rev 88, 919–982 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver J. A., Leon D. F., Gray S., Leonard J. J. & Bahnson H. T. Hemodynamic observations after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med 281, 822–827 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O. et al. Probing spinal circuits controlling walking in mammals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396, 11–18 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranto A. R. & Calabrese R. L. Neural control of the hearts in the leech, Hirudo medicinalis. II: Myogenic activity and its control by heart motor neurons. J Comp Physiol A 154, 381–391 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Meyrand P. & Moulins M. Myogenic oscillatory activity in the pyloric rhythmic motor system of Crustacea. J Comp Physiol A 158, 489–503 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Mayeri E., Koester J., Kupfermann I., Liebeswar G. & Kandel E. R. Neural control of circulation in Aplysia. I. Motoneurons. Journal of Neurophysiol 37, 458–475 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stent G. S., Thompson W. J. & Calabrese R. L. Neural control of heartbeat in the leech and in some other invertebrates. Physiol Rev 59, 101–136 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E. & Calabrese R. L. Principles of rhythmic motor pattern generation. Physiol Rev 76, 687–717 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Z. S. & Kim S. K. The early bird catches the worm: new technologies for the Caenorhabditis elegans toolkit. Nat Rev Gen 12, 793–801 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owald D., Lin S. & Waddell S. Light, heat, action: neural control of fruit fly behaviour. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370, 20140211 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N. & Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 314, 1–340 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson D. G. & Thomson J. N. The pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 275, 299–325 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G. et al. Light Activation of Channelrhodopsin-2 in Excitable Cells of Caenorhabditis elegans Triggers Rapid Behavioral Responses. Curr Biol 15, 2279–2284 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr R. A. et al. Optical imaging of calcium transients in neurons and pharyngeal muscle of C. elegans. Neuron 26, 583–594 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer W. R. Neurophysiological methods in C. elegans: an introduction. Wormbook 1–4, doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.113.1 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starich T. A., Lee R. Y. N., Panzarella C., Avery L. & Shaw J. E. eat-5 and unc-7 represent a multigene family in Caenorhabditis elegans involved in cell-cell coupling. J Cell Biol 134, 537–548 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starich T. A., Miller A., Nguyen R. L., Hall D. H. & Shaw J. E. The Caenorhabditis elegans innexin INX-3 is localized to gap junctions and is essential for embryonic development. Dev Biol 256, 403–417 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Dent J. A. & Roy R. Regulation of intermuscular electrical coupling by the Caenorhabditis elegans innexin inx-6. Mol Biol Cell 14, 2630–2644 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplantez T., Dupont E., Severs N. J. & Weingart R. Gap Junction Channels and Cardiac Impulse Propagation. J Membr Biol 218, 13–28 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. & Horvitz H. R. Effects of starvation and neuroactive drugs on feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Zool 253, 263–270 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtonda B. B. & Avery L. CCA-1, EGL-19 and EXP-2 currents shape action potentials in the Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx. J Exp Biol 208, 2177–2190 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N., Irisawa H. & Kameyama M. Contribution of two types of calcium currents to the pacemaker potentials of rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol 395, 233–253 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. & Horvitz H. R. Pharyngeal pumping continues after laser killing of the pharyngeal nervous system of C. elegans. Neuron 3, 473–485 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski N. F., Padovan-Merhar O., Raizen D. M. & Fang-Yen C. Neural and genetic degeneracy underlies Caenorhabditis elegans feeding behavior. J Neurophysiol 112, 951–961 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüler C., Fischer E., Shaltiel L., Costa W. S. & Gottschalk A. Arrhythmogenic effects of mutated L-type Ca(2+)-channels on an optogenetically paced muscular pump in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep 5, 14427 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen D. M., Lee R. Y. N. & Avery L. Interacting genes required for pharyngeal excitation by motor neuron MC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 141, 1365–1382 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatla N., Droste R., Sando S. R., Huang A. & Horvitz H. R. Distinct Neural Circuits Control Rhythm Inhibition and Spitting by the Myogenic Pharynx of C. elegans. Curr Biol 25, 2075–2089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand J. B. Genetic analysis of the cha-1-unc-17 gene complex in Caenorhabditis. Genetics 122, 73–80 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso A., Grundahl K. M., Duerr J. S., Han H.-P. P. & Rand J. B. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-17 gene: a putative vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Science 261, 617–619 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifee O., Wei L. & Nonet M. L. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-64 locus encodes a syntaxin that interacts genetically with synaptobrevin. Mol Biol Cell 9, 1235–1252 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonet M. L., Saifee O., Zhao H., Rand J. B. & Wei L. Synaptic transmission deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans synaptobrevin mutants. J Neurosci 18, 70–80 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R. E. et al. Expression of multiple UNC-13 proteins in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Mol Biol Cell 11, 3441–3452 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B.-M. & Avery L. Serotonin Activates Overall Feeding by Activating Two Separate Neural Pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 32, 1920–1931 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. The genetics of feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 133, 897–917 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay J. P., Raizen D. M., Gottschalk A., Schafer W. R. & Avery L. eat-2 and eat-18 are required for nicotinic neurotransmission in the Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx. Genetics 166, 161–169 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen D. M. & Avery L. Electrical activity and behavior in the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron 12, 483–495 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokala N., Liu Q., Gordus A. & Bargmann C. I. Inducible and titratable silencing of Caenorhabditis elegans neurons in vivo with histamine-gated chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111, 2770–2775 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. D. et al. FMRFamide-like FLP-13 Neuropeptides Promote Quiescence following Heat Stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 24, 2406–2410 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. W. & Wilson R. I. Transient and Specific Inactivation of Drosophila Neurons In Vivo Using a Native Ligand-Gated Ion Channel. Curr Biol 23, 1202–1208 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen D. M., Song B.-M., Trojanowski N. F. & You Y.-J. Methods for measuring pharyngeal behaviors. Wormbook 1–13, doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.154.1 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. Motor neuron M3 controls pharyngeal muscle relaxation timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Biol 175, 283–297 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang-Yen C., Avery L. & Samuel A. D. T. Two size-selective mechanisms specifically trap bacteria-sized food particles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 20093–20096 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. & Shtonda B. B. Food transport in the C. elegans pharynx. J Exp Biol 206, 2441–2457 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. & Horvitz H. R. A cell that dies during wild-type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell 51, 1071–1078 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski N. F., Nelson M. D., Flavell S. W., Fang-Yen C. & Raizen D. M. Distinct Mechanisms Underlie Quiescence during Two Caenorhabditis elegans Sleep-Like States. J Neurosci 35, 14571–14584 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Y. N., Sawin E. R., Chalfie M., Horvitz H. R. & Avery L. EAT-4, a homolog of a mammalian sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter, is necessary for glutamatergic neurotransmission in caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 19, 159–167 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent J. A., Davis M. W. & Avery L. avr-15 encodes a chloride channel subunit that mediates inhibitory glutamatergic neurotransmission and ivermectin sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 16, 5867–5879 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. W. et al. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans Na,K-ATPase alpha-subunit gene, eat-6, disrupt excitable cell function. J Neurosci 15, 8408–8418 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. W., Fleischhauer R., Dent J. A., Joho R. H. & Avery L. A Mutation in the C. elegans EXP-2 Potassium Channel That Alters Feeding Behavior. Science 286, 2501–2504 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek M., Niacaris T., Steger K. A., Avery L. & Thomas J. H. eat-11 encodes GPB-2, a G(5)beta ortholog that interacts with G(o)alpha and G(q)alpha to regulate C. elegans behavior. Curr Biol 11, 288–293 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger K. A. & Avery L. The GAR-3 Muscarinic Receptor Cooperates With Calcium Signals to Regulate Muscle Contraction in the Caenorhabditis elegans Pharynx. Genetics 167, 633–643 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa T. et al. Regulation of the UNC-18-Caenorhabditis elegans syntaxin complex by UNC-13. J Neurosci 19, 4772–4777 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J. E. Synaptic function. Wormbook 1–14, doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.69.1 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. G., Abbott L. F. & Marder E. Activity-dependent changes in the intrinsic properties of cultured neurons. Science 264, 974–977 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger K. A., Shtonda B. B., Thacker C. M., Snutch T. P. & Avery L. The C. elegans T-type calcium channel CCA-1 boosts neuromuscular transmission. J Exp Biol 208, 2191–2203 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-W. et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499, 295–300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Q. et al. Proprioceptive Coupling within Motor Neurons Drives C. elegans Forward Locomotion. Neuron 76, 750–761 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski N. F. & Raizen D. M. Neural Circuits: From Structure to Function and Back. Curr Biol 25, R711–R713 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. The neuronal genome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Wormbook 1–106, doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.161.1 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon E. B., Saari B. & Anderson P. Muscle-specific functions of ryanodine receptor channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci 111, 2885–2895 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz H. R., Chalfie M., Trent C., Sulston J. E. & Evans P. D. Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 216, 1012–1014 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. M., Franks C. J., Walker R. J., Burke J. F. & Holden-Dye L. M. Regulation of the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans by 5-HT, octopamine, and FMRFamide-like neuropeptides. J Neurobiol 49, 235–244 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou S., Marsden D., Franks C. J., Walker R. J. & Holden-Dye L. M. Role of a FMRFamide-like family of neuropeptides in the pharyngeal nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurobiol 65, 304–319 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou S., Holden-Dye L. M. & Walker R. J. The actions of Caenorhabditis elegans neuropeptide-like peptides (NLPs) on body wall muscle of Ascaris suum and pharyngeal muscle of C. elegans. Acta Biol Hung 59, 189–197 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowski N. F. & Fang-Yen C. Simultaneous Optogenetic Stimulation of Individual Pharyngeal Neurons and Monitoring of Feeding Behavior in Intact C. elegans. Methods Mol Biol 1327, 105–119 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L., Raizen D. M. & Lockery S. R. Electrophysiological methods. Methods Cell Biol 48, 251–269 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]