Abstract

Patient: Female, 55

Final Diagnosis: Mantle cell lymphoma

Symptoms: Cytokine release syndrome • hypoglycemia • hypotension • splenic rupture • splenomegaly • vision loss

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Case Report

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Rituximab is a therapeutic monoclonal antibody that is used for many different lymphomas. Post-marketing surveillance has revealed that the risk of fatal reaction with rituximab use is extremely low. Splenic rupture and cytokine release syndrome are rare fatal adverse events related to the use of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, especially in aggressive malignancies with high tumor burden.

Case Report:

A 55-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and type B symptoms and was diagnosed with mantle cell lymphoma. Initial peripheral blood flow cytometry showed findings that mimicked features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Further treatment with rituximab led to catastrophic treatment complications that proved to be fatal for the patient.

Conclusions:

Severe cytokine release syndrome associated with biologics carries a very high morbidity and case fatality rate. With this case report we aim to present the diagnostic challenge with small B-cell neoplasms, especially mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic lymphomas, and underscore the importance of thorough risk assessment for reactions prior to treatment initiation.

MeSH Keywords: Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions; Lymphoma, Mantle-Cell; Splenic Rupture

Background

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that has significant efficacy in various individual lymphoid malignancies. Rituximab is generally well tolerated; infusion reaction associated with rituximab administration is well recognized and is usually associated with the first infusion. However, there is high potential for significant toxicity, which is correlated with the degree of tumor burden. Here, we present the case of a patient with aggressive mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) initially presenting with leukocytosis and splenomegaly mimicking chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) on immunophenotypic features. Further treatment with rituximab caused catastrophic complications, including cytokine release syndrome and splenic rupture. Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) account for the majority of small B-cell neoplasms (SBCNs) that express CD5 without CD10, and could present as a diagnostic challenge due to its overlapping clinical, morphologic and immunophenotypic features.

Case Report

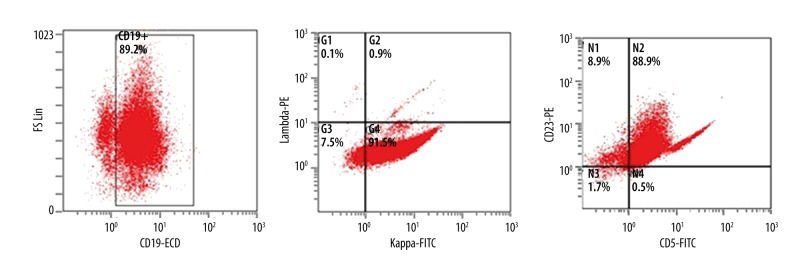

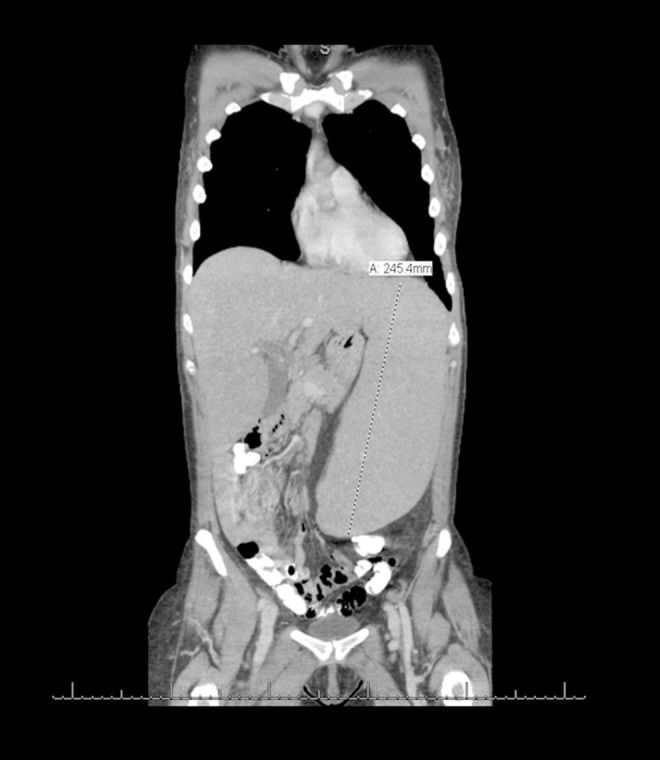

A 60-year-old white woman presented with abdominal pain, drenching night sweats, early satiety, anorexia, and significant weight loss during the previous 8 months. Prior to this she was in good health and taking no medications. On physical examination she had generalized lymphadenopathy and massive splenomegaly. Complete blood cell count showed pancytopenia, normal blood chemistry, and elevated LDH 778 U/L (Table1). Differential count showed predominant lymphocytosis. Peripheral smear showed increased lymphocytes, condensed nuclear chromatin, rare smudge cells and occasional left-shifted neutrophils. CT imaging showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly measuring 24×17 cm (Figure 1). Flow cytometry showed a large monoclonal B-cell population, kappa light chain restriction, dim CD19, CD20, CD5, and variable expression of CD23. This population demonstrated moderate to bright CD38 and was negative for CD10 and CD11c (Figure 2). The findings were most compatible with a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Results of a FISH panel was reported pending at that point.

Table 1.

Blood work at the time of presentation and 4 hours post rituximab infusion.

| Labs | At presentation | 4 hours post Rituximab |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 9.4 g/dL | 6.2 g/dL |

| WBC | 44 000/μL | 24 000/μL |

| Platelet count | 106 000/μL | 74 000/μL |

| Serum potassium | 4.4 mEq/L | 7.1 mEq/L |

| Serum uric acid | 2.2 mg/dL | 6.8 mg/dL |

| LDH | 778 U/L | 8750 U/L |

| Lactate | – | >30 mmol/L |

| PT | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| PTT | 14 | 28.8 |

| D-Dimer | – | 12. 25 µg/mL |

| Fibrinogen | 296 mg/dL | |

| Haptoglobin | – | <7 mg/dL |

| AST | 44 U/L | 1326 U/L |

| ALT | 38 U/L | 200 U/L |

| T. bilirubin | 1.2 mg/dL | 8.2 mg/dL |

| Serum Cortisol | – | 122 μg/dL |

Figure 1.

CT scan image showing massive splenomegaly.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry showing a large monoclonal B-cell population Kappa light chain restriction, dim CD19, CD20, CD5, and variable expression of CD23.

Due to B symptoms and ongoing pain, a decision was made to initiate FCR chemotherapy (Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, and Rituximab). A bone marrow biopsy was done and further rituximab treatment was initiated a day later. At 30 minutes after initiation of rituximab, the patient developed severe rigors, chills, and nausea. She became hypotensive, hypoglycemic, and developed severe respiratory failure requiring intubation and vasopressor support. Her clinical features and work-up (Table 1) were consistent with cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and she was started on systemic steroids. She was treated with antibiotics and aggressive fluid resuscitation, but developed acute renal failure requiring bicarbonate infusion and emergent hemodialysis. An echocardiogram showed a dilated right ventricle with decreased ejection fraction and a CT scan showed findings concerning for splenic infarction.

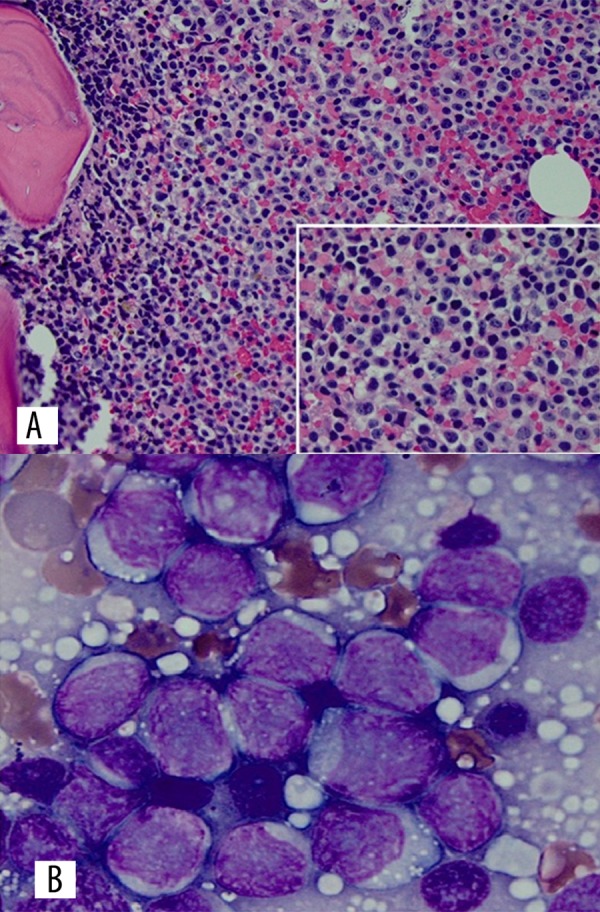

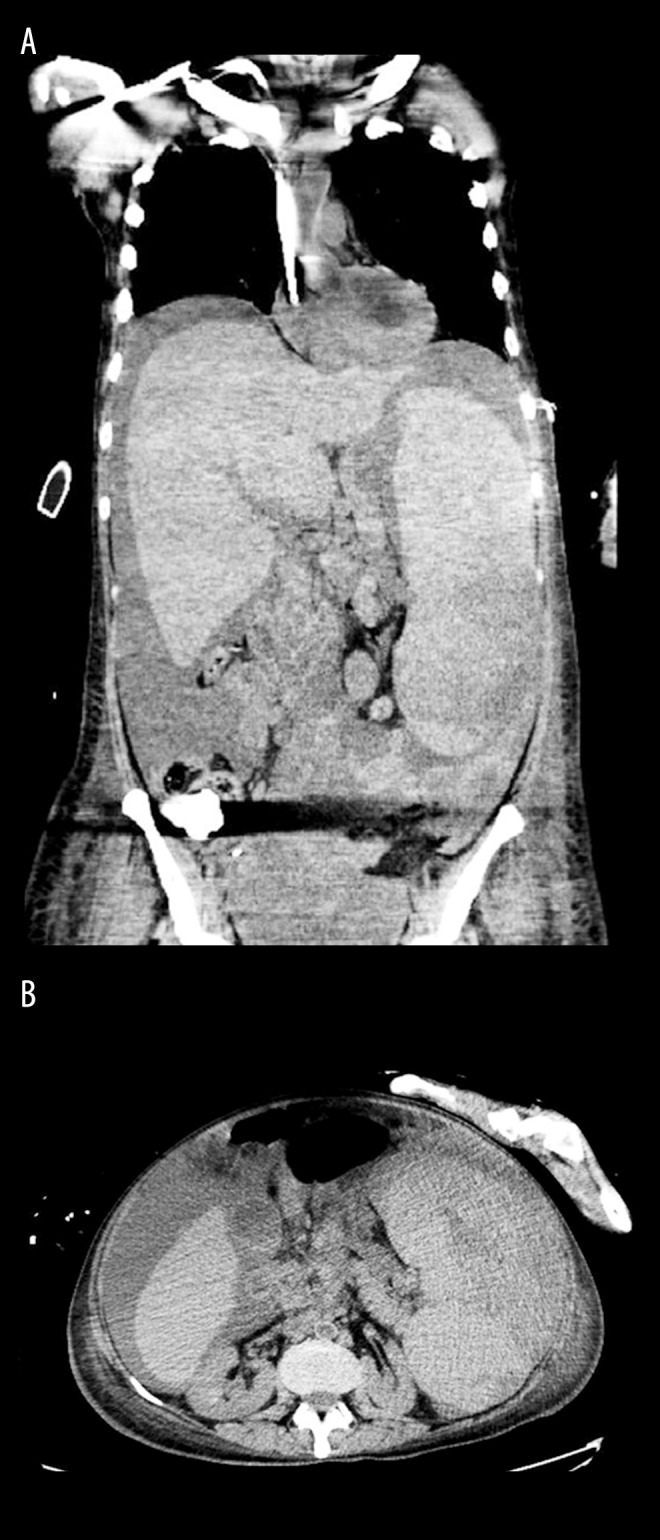

By this time the peripheral blood FISH panel showed t (11; 14) consistent with MCL. A bone marrow biopsy showed very aggressive MCL with associated TP53 deletion and Ki-67 proliferation index 60% (Figure 3). Although her clinical status improved, she developed severe vision loss in both eyes. On day 30 she developed intractable abdominal pain and severe thrombocytopenia. An urgent CT scan demonstrated splenic rupture and hemoperitoneum (Figure 4). She received palliative care and died shortly thereafter.

Figure 3.

(A) Bone marrow core biopsy (40× magnification) (insert: 100× magnification) showing sheets of large transformed lymphocytes with occasional prominent nucleoli. (B) Bone marrow aspirate (100× magnification) showing large lymphoid cells with slightly folded nuclei and vesicular chromatin.

Figure 4.

(A, B) CT scan images showing splenic rupture.

Discussion

MCL is an aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with the worst prognosis of all lymphomas. Although not curable outside of transplantation, frequent remissions (60–90%) can be obtained, but they are short (1–2 years) [1]. MCL is a SBCN that is often misdiagnosed as CLL. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping often helps differentiate CLL from MCL, and a characteristic CLL phenotype is considered essentially diagnostic [2]. There is significantly higher expression of CD23 in CLL. MCL typically is negative for CD23, but 25% of cases can be dimly positive [3,4]. CLL, on the other hand, can occasionally be CD23-negative. Thus, NHL often is less obvious and confounds the diagnosis if a leukemic phase occurs at presentation. MCL is more specifically identified by the presence of the translocation t (11; 14) (q13; q32), which juxtaposes the cyclin D1 gene to the immunoglobulin locus. Rare cyclin D1-negative variants do exist, which may be characterized by increased expression of cyclin D2. At present, FISH assay is by far the most sensitive and specific technique for t (11; 14) identification [5]. This should be considered and waited upon in newly diagnosed CLL patients with atypical features, especially B grade symptoms at initial presentation, massive splenomegaly, and immunophenotypic feature showing moderate bright CD20 and bright surface light chain expression. Given the importance of stem cell transplants for MCL patients, it is important to recognize this, as fludarabine therapy can impair successful collection of stem cells [6]. Bone marrow biopsy is not required for diagnosis of CLL, but should be strongly considered in atypical presentations, discordance in the immunophenotypic markers, and presence of cytopenias, preferably prior to treatment initiation.

Rituximab-induced severe CRS or splenic rupture is very rarely reported in literature. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is a potentially fatal toxicity that has been associated with administration of any therapeutic monoclonal antibody, with the mildest form manifested as infusion reaction. The incidence and severity of adverse infusion events, in 80% of the cases, are reported mostly during the first infusion of rituximab [7]. In patients with peripheral lymphocytosis, this is dependent on the number of circulating CD20+ tumor cells [8]. There is emerging evidence implicating IL-6 as a central mediator in CRS. Tocilizumab (humanized anti-IL-6 receptor antibody) is increasingly being used as a first-line immunosuppressive therapy in clinical trials, with dramatic responses, but data on rituximab-induced severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome is limited at this point [9]. The exact incidence of splenic rupture associated with rituximab is not reported; however, this needs to be considered in relation to the aggressiveness of the tumor, and possible splenic capsule infiltration by malignant cells with the potential to have dramatic tumor breakdown upon treatment with a very effective anti-tumor biologic agent. Ophthalmic adverse effects of rituximab have been reported, including transient ocular edema, transient visual changes, and severe loss of visual acuity; however, these are very rare [7].

Conclusions

When evaluating SBCN, it is important to distinguish CLL from MCL and other non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas that have a leukemic phase, especially with atypical presentations. Although there is no single pathognomonic karyotype that distinguishes CLL, cytogenetic studies and FISH analysis can provide prognostic information and important clues to differentiate it from other non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Rituximab is a drug that is widely used in clinical oncology practice but has potential to cause complications of catastrophic proportions unless careful attention is paid to assess the risks. In the absence of clear guidelines, it is important to perform clinical risk assessment with the use of biologics because the severity of reactions could correlate with the aggressiveness and burden of the disease. Strong consideration should be given to aggressive prophylactic hydration, pre-treatment with steroids, anti-hyperuricemic therapy, antihistamines, and holding or dose reduction of rituximab with the first cycle. The post-marketing surveillance database on rituximab indicates a mortality rate of 0.04–0.07% associated with the drug; however, due to its increasing use, there should be a high index of suspicion for these adverse effects because they are life-threatening.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest or sources of funding declared for this report.

References:

- 1.Ghielmini M, Zucca E. How I treat mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114:1469–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-179739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho AK, Hill S, Preobrazhensky SN, Miller ME, et al. Small B-cell neoplasms with typical mantle cell lymphoma immunophenotypes often include chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:27–32. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPAG4VR4IPGHZ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klapper W. Histopathology of mantle cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2011;48:148–54. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus TS, Sillings CN, Saxe DF, et al. The role of CD11c expression in the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:271–77. doi: 10.1309/AJCPOGCI3DAXVUMI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JY, Gaillard F, Moreau A, et al. Detection of translocation t (11; 14)(q13; q32) in mantle cell lymphoma by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1449–52. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laszlo D, Galieni P, Raspadori D, et al. Fludarabine containing-regimens may adversely affect peripheral blood stem cell collection in low-grade non Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:157–61. doi: 10.3109/10428190009057639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rituxan® (rituximab) [package insert] South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc.; Cambridge, MA: Biogen Idec Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler U, Jensen M, Manzke O, et al. Cytokine-release syndrome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and high lymphocyte counts after treatment with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody [rituximab, IDEC-C2B8] Blood. 1999;94:2217–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014;124:188–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]