Abstract

The synthesis of a series of conformationally locked mannopyranosyl thioglycosides in which the C6-O6 bond adopts either the gauche,gauche, gauche,trans, or trans,gauche conformation is described, and their influence on glycosylation stereoselectivity investigated. Two 4,6-O-benzylidene protected mannosyl thioglycosides carrying axial or equatorial methyl groups at the 6-position were also synthesized and the selectivity of their glycosylation reactions studied to enable a distinction to be made between steric and stereoelectronic effects. The presence of an axial methoxy group at C6 in the bicyclic donor results in a decreased preference for formation of the β-mannoside whereas an axial methyl group has little effect on selectivity. The result is rationalized in terms of through space stabilization of a transient intermediate oxocarbenium ion by the axial methoxy group resulting in a higher degree of SN1-like character in the glycosylation reaction. Comparisons are made with literature examples and exceptions are discussed in terms of pervading steric effects layered on top of the basic stereoelectronic effect.

Keywords: glycosylation, stereoelectronic effects, stereosectivity, conformation

Introduction

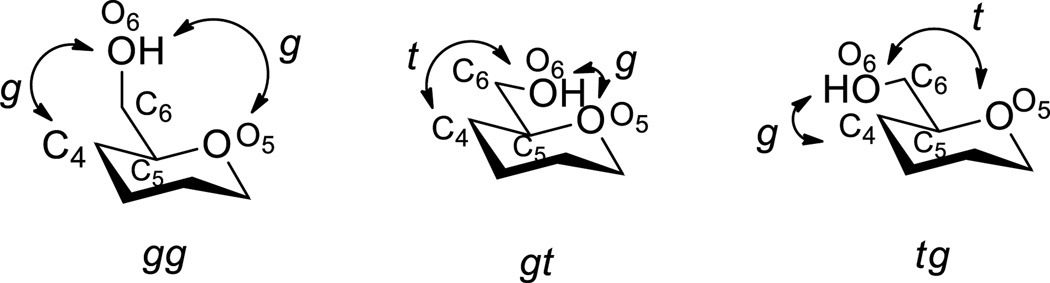

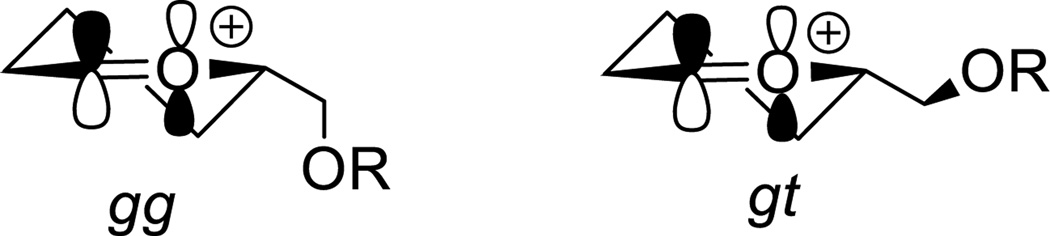

The hydroxymethyl side chain of the hexopyranoses and their derivatives is considered to occupy an equilibrium mixture of three staggered conformations described as the gauche,gauche (gg), gauche,trans (tg), and trans,gauche (tg) conformers according to the relationship of the C6-O6 bond to the C5-O5 and C5-C4 bonds, respectively (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1.

The gg, gt, and tg conformations of the hydroxymethyl chain.

In freely rotating systems the composition of the equilibrium mixture of conformers is principally a function of orientation of the C4 substituent and of the anomeric center, although other factors such as solvent, the protecting group array, and the size and chirality of the aglycone are increasingly recognized as contributing factors.[2] In the context of glycosylation, following the seminal work of Bols,[3] the conformation of the side chain is also recognized to be an important factor in the reactivity of glycosyl donors.[4] Thus, the disarming effect of the 4,6-O-benzylidene acetal-type protecting group recognized by Fraser-Reid[5] and a part of the Wong relative reactivity value index,[6] was established to be the result of locking the C5-C6 bond in the tg conformation thereby maximizing the electron-withdrawing effect of the C6-O6 and its destabilizing effect the nascent glycosyl oxocarbenium ion.[3, 4g] NMR and computational studies with conformationally unrestricted 1-ethoxy-5-alkoxylmethyl tetrahydropyrylium ions reveal that the pendant alkoxymethyl group prefers the gg conformation when it is pseudoequatorial to the half-chair of the oxocarbenium ion, and a gauche conformation projecting the C6-O6 bond toward the center of positive charge when it is pseudoaxial to an oxocarbenium ion half-chair conformation.[7] These observations are consistent with the work of the Woerpel and Bols groups and others according to which oxocarbenium ions are stabilized electrostatically through space by remote C-O bonds.[8]

Most recently it has been observed that side chain conformation influences the stereoselectivity of glycosylation reactions on both the sialic acids and the 2-deoxyglucopyranosides leading to the suggestion that the gg conformation favors nucleophilic attack on the opposite face of the “oxocarbenium ion” to the one populated by the C6-O6 bond.[4f, 9] In this article we report on the synthesis and use of a series of conformationally locked bicyclic mannosyl donors in which the C6-O6 bond is held in either the gg, gt, or tg conformation, to probe the effect of side chain conformation on glycosylation stereoselectivity. We find that the gg configured system has lower β-selectivity than either the gt or the tg comparators consistent with stabilization of the glycosyl oxocarbenium ion by the gg methoxy group and increased SN1-like character for the glycosylation reaction. The observation is discussed in the context of previous papers demonstrating the higher reactivity of the gg conformer leading to the formulation of a general picture of side chain conformation on glycosyl donor reactivity and selectivity.

Results and Discussion

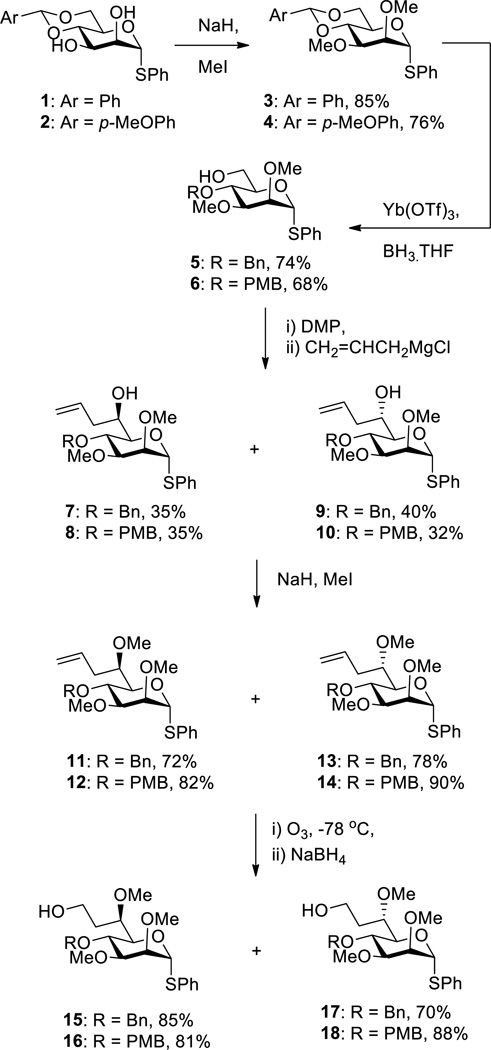

Adapting the method employed by Bols for the methyl glucosides[3] and in our laboratory for the methyl galactosides,[4g] the benzylidene thioglycoside 1[10] was converted to the 2,3-di-O-methyl analogue 3 by alkylation under standard conditions and then to the 4-O-benzyl-6-ol 5 by selective partial reduction of the acetal with the borane•THF complex in the presence of ytterbium triflate[11] (Scheme 1). Oxidation with the Dess-Martin periodinane[12] gave an aldehyde that was reacted immediately with a commercial solution of allylmagnesium chloride in THF to afford a 1:1 mixture of the d-glycero-d-manno and l-glycero-d-manno thiononopyranosides 7 and 9, respectively. The relative configurations of 7 and 9 were assigned retrospectively following subsequent conversion to less conformationally mobile bicyclo[4,4,0]decane-type skeletons. After separation 7 and 9 were subject to further methylation to give 11 and 12, respectively, followed by ozonolytic alkene cleavage with reductive work-up to afford the selectively protected 7-deoxy 4-O-benzyl thiooctosides 15 and 17 (Scheme 1). Application of the same reaction sequence to the 4,6-O-p-methoxybenzylidene acetal 2[13] gave the analogous 7-deoxy 4-O-p-methoxybenzyl thiooctosides 16 and 18 (Scheme 1)..

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Selectively Protected Phenyl α-d-glycero-d-manno and α-l-glycero-d-manno-thiooctopyranosides 15-18.

Treatment of the benzyl ethers 15 and 17 with boron trichloride in dichloromethane followed by tosylation of the primary alcohol gave the 5,8-anhydro octofuranosides 20 and 22 with the d-glycero-d-manno- and l-glycero-d-manno- configurations, respectively, and not the anticipated 4,8-anhydro octopyranoside isomers. These reactions are understood as proceeding via a Lewis acid mediated endocyclic opening of the pyranoside ring following debenzylation, and subsequent ring closure to the furanosides 19 and 21, respectively. Selective sulfonylation of the primary alcohol and ring closure by displacement of the tosylate group then gives the observed products. Indeed, omission of the tosylation step enabled isolation of 19 and 21 in good yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Thiopyranoside to Thiofuranoside rearrangement on Removal of 4-O-Benzyl Ethers with Boron Trichloride.

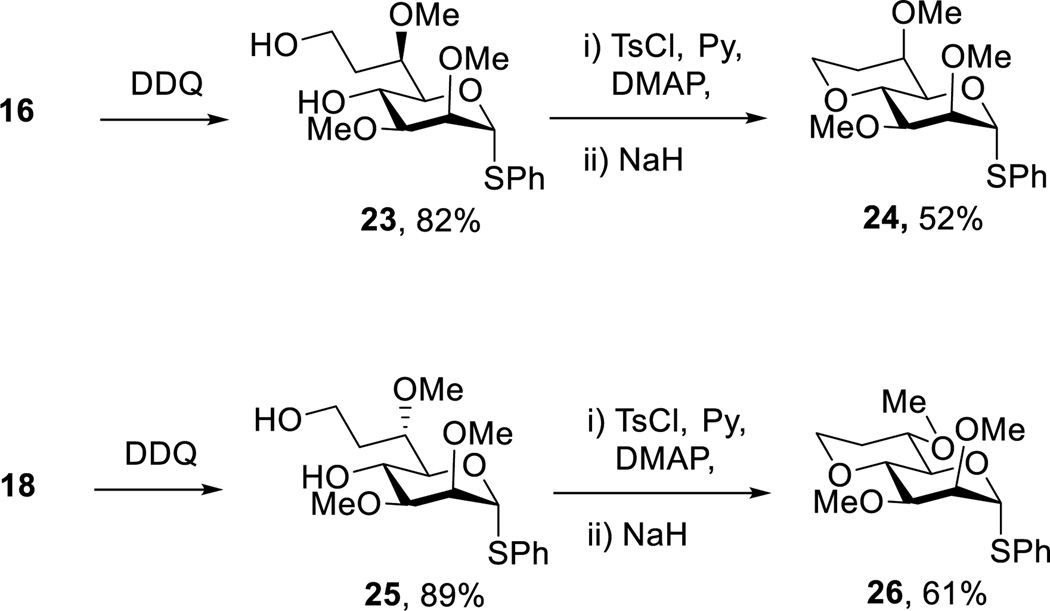

To circumvent the Lewis acid mediated pyranoside to furanoside rearrangement, attention was refocused on the 4-O-p-methoxybenzyl ethers 16 and 18, which on treatment with DDQ in wet dichloromethane gave the required octopyranosyl diols 23 and 25 uneventfully. Tosylation of the primary alcohol groups in 23 and 25 and subsequent treatment with sodium hydride then afforded the desired 4,8-anhydrothiooctopyranosides 24 and 26 in the d-glycero-d-manno- and l-glycero-d-manno- series, respectively (Scheme 3). It is noteworthy that, whereas the cyclization of 19 and 21 to 20 and 22, respectively, took place spontaneously on monotosylation in pyridine, the formation of 24 and 26 from 23 and 25 did not occur under the same conditions and required activation of the residual hydroxyl group at the 4-position in the form of the sodium salt. The isolation of 24 and 26, with their rigid bicyclic skeletons enabled the straightforward assignment of configuration at the 6-position through routine analysis of coupling constants, and so retroactively the assignment of 7–10 and all intermediate products.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Bicyclic Octosyl Donors Isomeric at the 6-Position

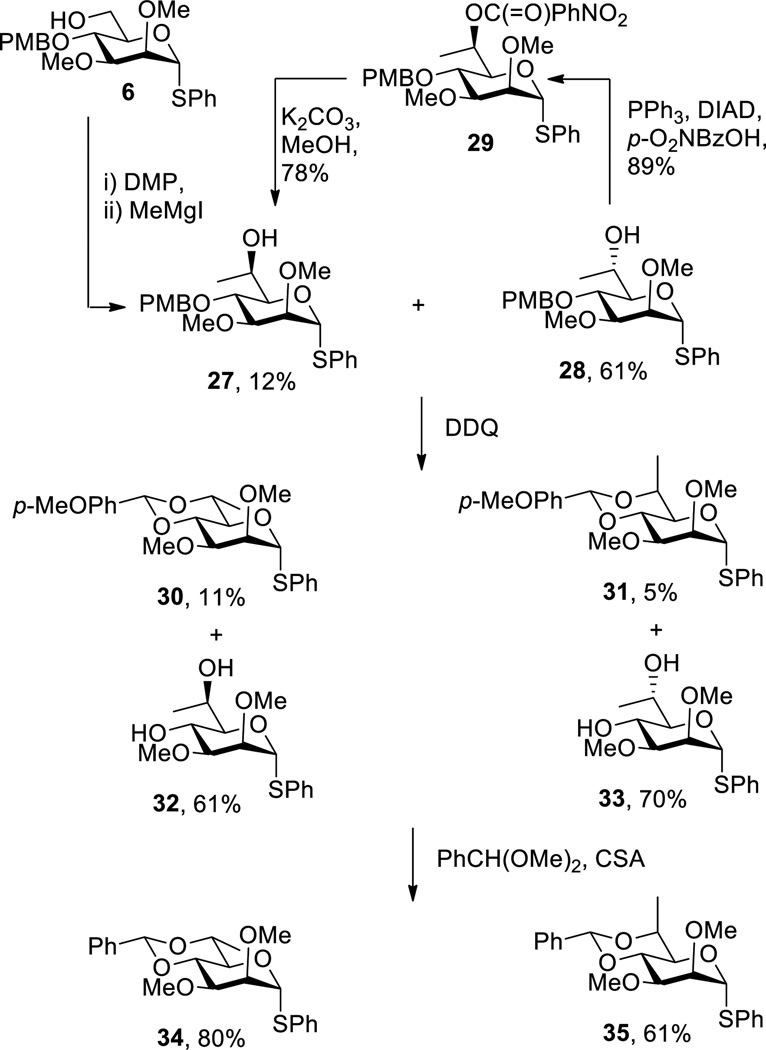

In order to be able to compare the influence of alkoxy groups with alkyl groups at the 6-position on glycosylation stereochemistry a pair of 4,6-O-benzylidene protected 7-deoxy heptothiopyranosides diastereomeric at the 6-position were prepared. Thus, Dess-Martin oxidation of 6 followed by treatment with methylmagnesium iodide in ether gave the d-glycero-d-manno and l-glycero-d-manno heptosides 27 and 28, whose configuration was assigned following subsequent benzylidene acetal formation, in a ratio of approximately 1:5. The diastereoselectivity observed in this Grignard addition contrasts significantly with that observed on addition of allylmagnesium chloride in THF to the identical aldehyde derived from 6 (Scheme 1) and presumably reflects the change in counter-ion and solvent.

A portion of the major isomer 28 was readily converted to the minor one 27 by means of the Mitsunobu reaction[14] and the p-nitrobenzoate ester 29. Treatment of 27 and 28 with DDQ in wet acetonitrile gave the corresponding diols 32 and 33 in moderate yield together with minor amounts of the p-methoxybenzylidene acetals 30 and 31. These acetals, whose configurations were readily assigned by standard means, arise from intramolecular nucleophilic attack by the 6-hydroxy groups competing with quenching by water at the level of the intermediate benzylic cations.[15] Finally, installation of the benzylidene acetals in 34 and 35 took place unambiguously under standard transacetalization conditions employing camphor-10-sulfonic acid as catalyst (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the 7-Deoxy d-Glycero-d-manno- and l-Glycero-d-manno Thioheptosides 34 and 35.

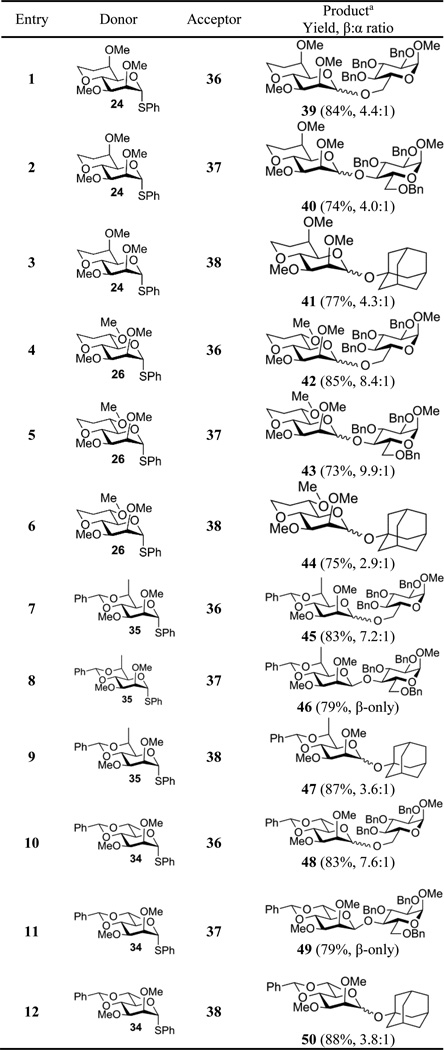

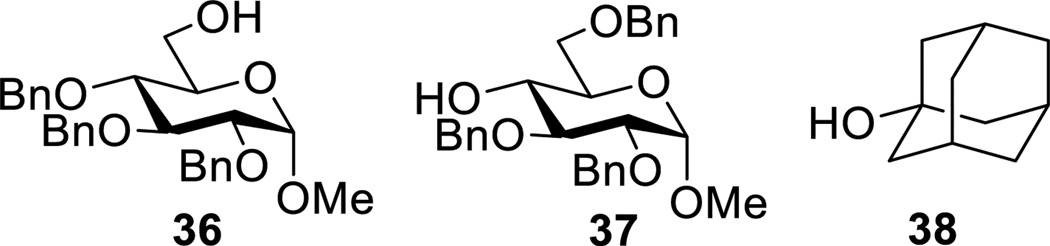

With four thioglycosides in hand a series of glycosylation reactions were conducted under a set of standard conditions involving donor preactivation at −78 °C in dichloromethane in the presence of 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylpyrimidine (TTBP)[16] with the combination of 1-benzenesulfinyl piperidine (BSP)[17] and triflic anhydride followed by addition of the acceptor alcohol. For the benzylidene acetals 34 and 35, consistent with the strongly disarming properties of this protecting group, activation by the BSP/Tf2O couple was slow at −78 °C, therefore activation was conducted at −60 °C after which the reaction mixture was cooled to −78 °C for addition of the acceptor. All reactions were conducted at the same concentration of donor, acceptor, activating couple and base, and were quenched at −78 °C by the addition of sat. NaHCO3 solution prior to work up. One primary 36, one secondary 37 and one tertiary alcohol 38 were employed as acceptor leading to the matrix of glycosylation reactions presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Glycosylation reactions

Mean of two independent experiments

For each glycosylation product, the anomeric stereoselectivity could be rapidly and unambiguously determined on the basis of the chemical shift (δH5) of the H5 resonance in the mannose moiety as in the simple 4,6-O-benzylidene acetals.[18] In each case this assignment was supported by measurement of the diagnostic anomeric 1JCH heteronuclear coupling constant in the mannose ring.[19]

With donor 24 and its axial 6-OMe group mimicking the gg conformation all three acceptor alcohols display modest β-selectivity of approximately 4:1 (Table 1, entries 1−3). With the diastereomeric donor 26 and equatorial 6-OMe group positioned to imitate the gt conformation selectivities are between 8 and 10:1 in favor of the β-isomer for the two carbohydrate acceptors 36 and 37 (Table 1, entries 4 and 5), but are lower when the tertiary alcohol 1-adamantanol is employed as acceptor (Table 1, entry 6). With the tg-configured donors 35 and 34 carrying either axial or equatorial methyl groups at the 6-position selectivity for the formation of the β-products was high with the two sugar acceptors (Table 1, entries 7, 8, 10 and 11) but again lower with adamantanol (Table 1, entries 9 and 12). Therefore, for the two carbohydrate acceptors 36 and 37, the effect of imposing the gg-conformation on the side chain as in donor 24) is one of reducing the β-selectivity compared to the gt and tg conformations (donors 26, and 35 and 34). We consider that this effect is not primarily a steric one arising from the methoxy group shielding the β-face of donor 24, as donor 35 has an axial methyl group in the same position, and methyl groups are larger than methoxy groups as judged by comparison of their steric A values (Me = 1.74 kcal.mol−1, OMe = 0.55–0.75 kcal.mol−1).[20] However, the possibility that the effect arises at least in part from differential shielding of the anomeric center by the methoxy groups in 24 and 26 cannot be completely excluded. That adamantanol does not fit the pattern observed with the two carbohydrate acceptors is due to lower selectivity observed with the gt-configured donor 26 and the two 6-methyl tg-configured donors 35 and 34 (Table 1, entries 6, 9, and 12) rather than to any significant change in selectivity with the gg-donor 24 (Table 1, entry 3). We hypothesize that this change in pattern with the tertiary alcohol adamantanol, to which we return below, is due at least in part to the increased steric bulk of the acceptor.

The reduced β-selectivity arising from the imposition of the gg conformation as in donor 24 is best understood in terms of stabilization of the positive charge at the anomeric center in a transient oxocarbenium ion by the C6-O6 bond, which is closer to and periplanar with the vacant π-orbital of the delocalized cation. As the oxocarbenium ion[21] is in equilibrium with the commonly observed[22] α-glycosyl triflate this stabilization results in a longer lifetime of the oxocarbenium ion and looser ion pairs leading to a reduction in selectivity (Scheme 5).[23] This rationale is consistent with computational work by Woerpel suggesting that pyranosyl oxocarbenium ions are stabilized when the side chain adopts the gg conformation.[7] Furthermore it is in full agreement with kinetic isotope effect measurements[24] and cation clock experiments,[25] both of which indicate a higher degree of SN1-like character in the formation of 4,6-O-benzylidene–protected α-mannosides than for their β-anomers which are closer to the SN2 end of the mechanistic spectrum for nucleophilic substitution.

Scheme 5.

Glycosylation mechanism for mannoside formation illustrating shift in the covalent donor – ion pair equilibria with side chain configuration.

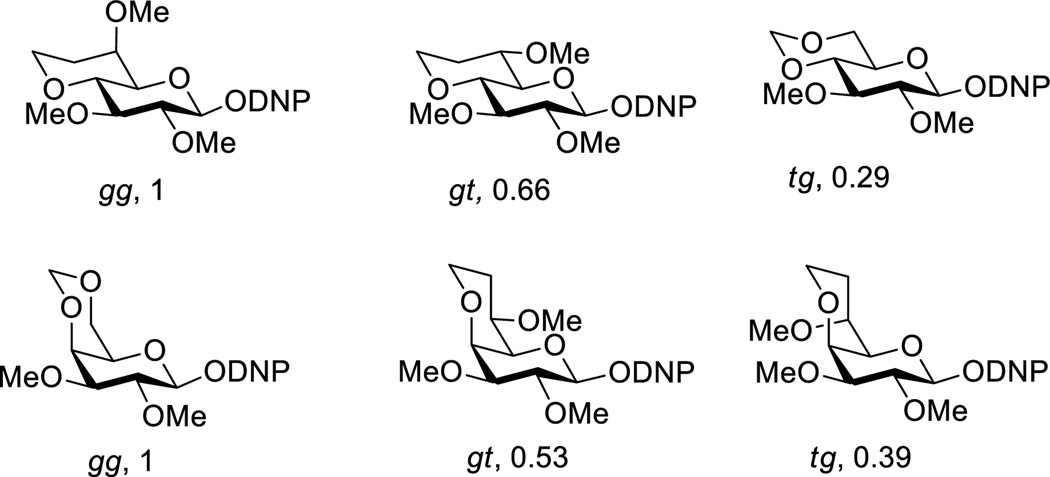

This stabilization of the glycosyl oxocarbenium ion by imposition of the gg conformation on the C6-O6 bond is also consistent with the work of the Bols and Crich laboratories on the relative rates of hydrolysis of both trans- and cis-fused models of 4,6-alkylidene-protected dinitrophenyl glycosides (Figure 3).[3, 4g] In both the glucose and the galactose series the gg system is more reactive than the gt and tg models reflecting the greater stabilization afforded to the positive charge developing at the anomeric center in the transition state for hydrolysis.

Figure 3.

Influence of the C6-O6 bond conformation on relative rates of 2,4-dinitrophenyl glycoside hydrolysis in the glucose and galactose series.

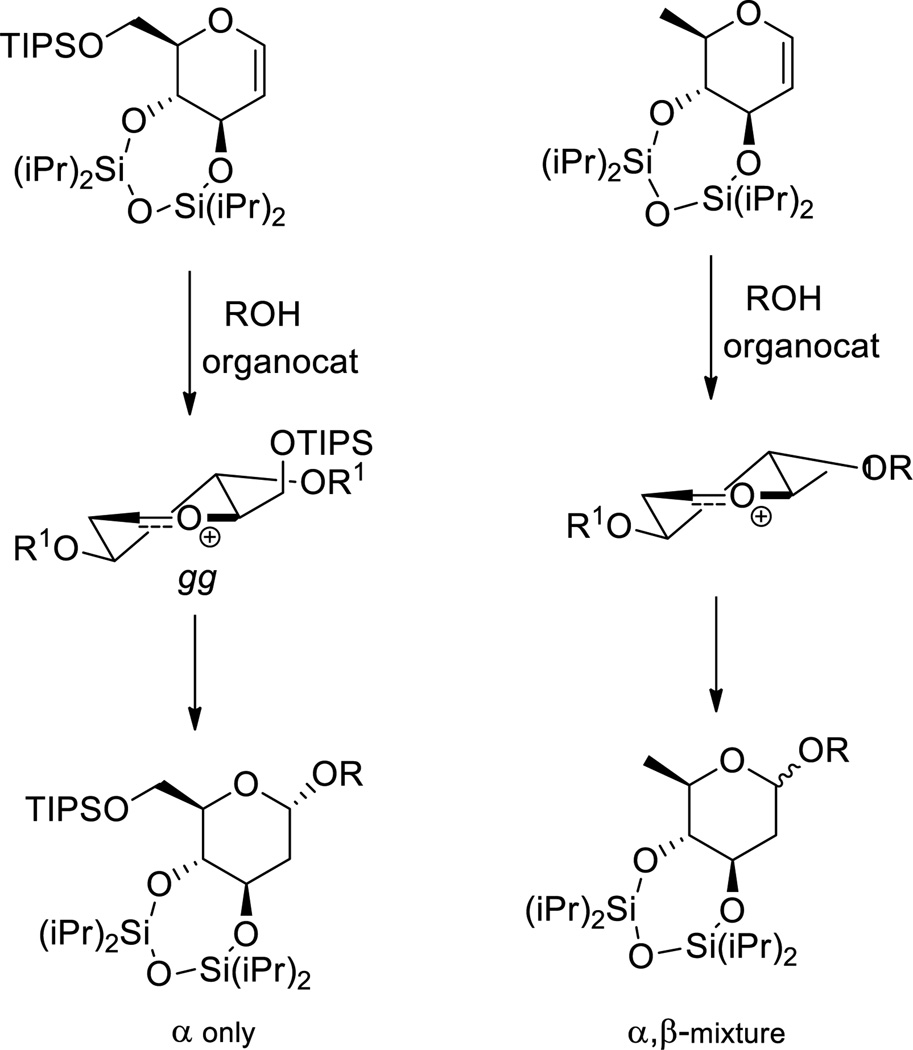

In a recent paper Galan and coworkers described the influence of a 6-O-(tri-isopropylsiloxy) substituent on the outcome of the organocatalytic addition of alcohols to trans-fused 3,4-O-(tetra-isopropyldisiloxane)-protected glycals in comparison with the corresponding 6-deoxy series.[9] While the 6-deoxy donor was found to give α,β-mixtures of products, the 6-O-silyl system was found to give exclusively the α-anomer (Scheme 6). The difference in selectivity was attributed on the basis of computational work to the preferential adoption of the gg conformation by the siloxy group and the corresponding stabilization by 2.6 kcal.mol−1 of the oxocarbenium ion with respect to the gt conformer.[9] Nevertheless, this stabilization of the gg over the gt conformer, which fits the general pattern, should not be interpreted to mean that the 6-O-siloxy substituted oxocarbenium ion is stabilized with respect to the 6-deoxy system studied; 6-deoxy sugars are considerably more reactive than their fully oxygenated counterparts because of the absence of an electron-withdrawing C-O bond. It is also noteworthy that mannopyranosyl donors protected with a Ley-type bisacetal protecting group spanning the 3- and 4-positions, analogous to the disiloxanes studied by Galan and coworkers, are highly α-selective in contrast to the β-selective 4,6-O-benzylidene protected mannosyl donors.[26]

Scheme 6.

Highly α-selective organocatalyzed addition to a conformationally locked glycal as a function of the side chain and its gg conformation. [Work in the 6-deoxy glycal was conducted on the l-enantiomer; its antipode is drawn here for ease of comparison].

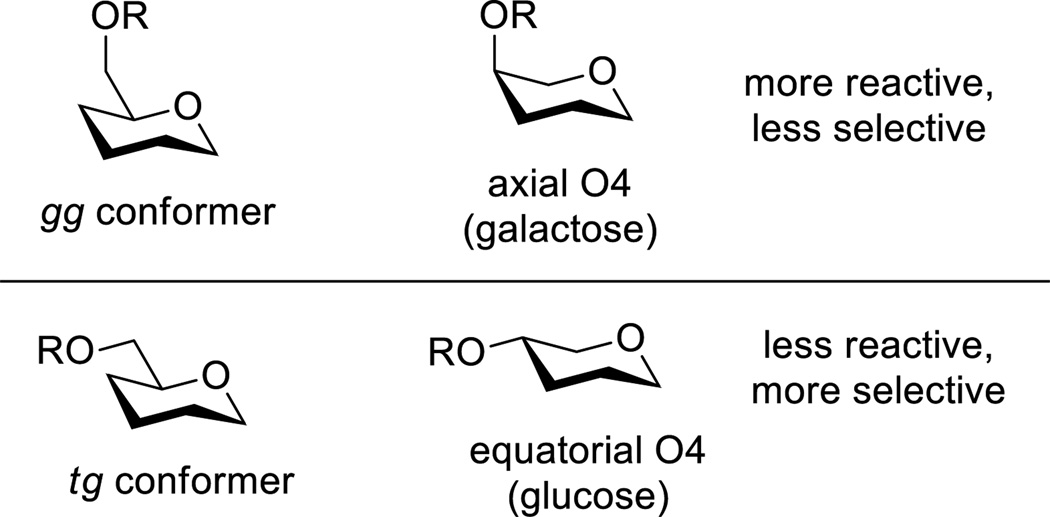

The difference in reactivity and selectivity between the tg and gg-conformers is most easily understood by comparison with standard gluco- and galactopyranosyl systems. Thus, the spatial relationship between O6 and the ring oxygen in the tg conformation is identical to that between the equatorial O4 and the ring oxygen in glucopyranosides, whereas the O6 and the ring oxygen in the gg conformer share the same spatial relationship as the axial O4 and the ring oxygen in galactopyranosides (Figure 4). The axial O4 in galactose and the gg conformer of the side chain are spatially closer to the ring oxygen and better able to stabilize positive charge on it, than the equatorial O4 in glucose and tg conformer of the side chain, resulting in the generally greater reactivity and α-selectivity of galactosyl over glucosyl systems[27] and in the greater reactivity[3, 4g] and now the α-selectivity of the gg over the tg confomers of the side chain. The ability of the axial O4 in galactose, and by extrapolation O6 in the gg conformer, to stabilize positive charge on the ring oxygen better than the equatorial O4 in glucose and consequently O6 in the tg conformer is usually considered in terms of a simple electrostatic effect with the electron density on axial group being closer to the positive charge than is the case with the equatorial group.[7, 8b, 8c, 28] Alternatively, the axial O4 in galactose (and O6 in the gg conformer) stabilize developing positive charge at the ring oxygen by through space donation of electron density, which is not possible with the equatorial O4 in glucose (and O6 in the tg conformer).[8e]

Figure 4.

Comparison of the spatial proximities of O6 in the gg and tg conformers and of O4 in galactosyl and glucosyl systems to the ring oxygen.

The electrostatic hypothesis for the increased stabilization of positive charge on the ring oxygen by an axial O4 or by O6 in the gg conformer, while satisfactory when making comparisons to an equatorial O4 or the tg conformer, respectively, does not extend to the gt conformer whose reactivity (Figure 3) and selectivity (Table 1) is intermediate between that of the gg and tg conformers. This is because the C6-O6 bonds in the gg and gt conformers are both gauche to the C5-ring oxygen bond thereby placing O6 equidistant from the ring oxygen (Figure 1) in the ground state conformation of the pyranose with the equatorial side chain and in the likely 4H5 and B2,5 conformers of the oxocarbenium ion. The apparent stabilization of the oxocarbenium ion by the gg conformation of the side chain as compared to the gt conformation, which presumably arises from through space donation of electron density into the π* orbital with which the C6-O6 bond has good overlap (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relationship of the C6-O6 bond to the oxocarbenium ion π* orbital in the gg and gt rotamers, illustrated for the 4H5 conformation.

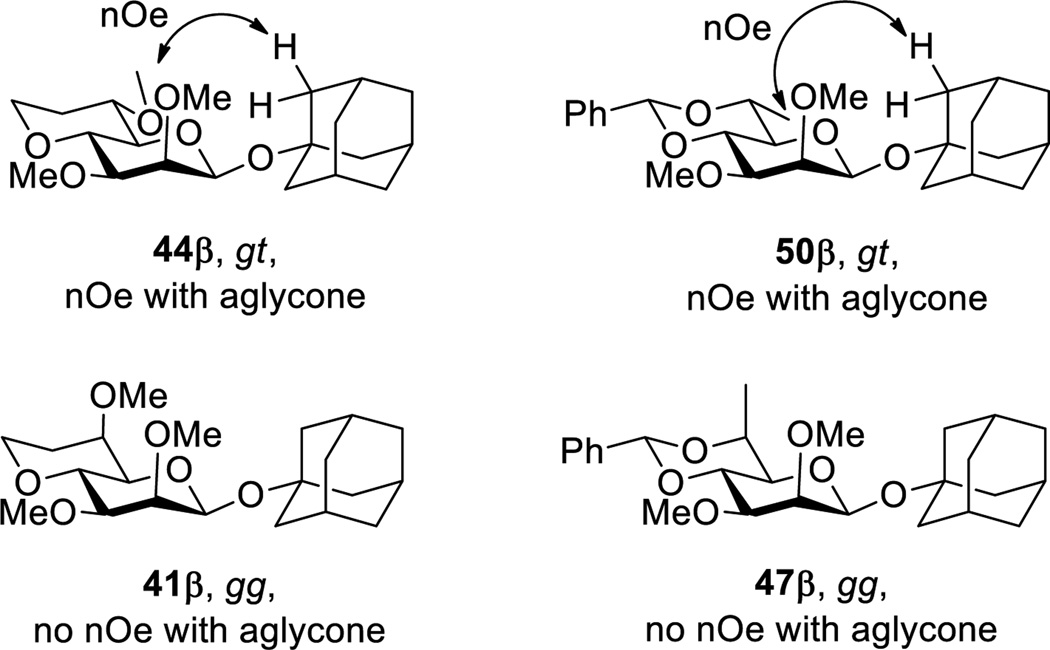

Exceptions to the overall pattern of the gg conformation of the C5-C6 bond stabilizing an intermediate pyranosyl oxocarbenium ion and thereby influencing reactivity and selectivity are apparent and can be explained by the layering of steric effects onto the basic stereoelectronic model. The use of the tertiary alcohol 1-adamantanol as acceptor in the present study is one such exception. Thus, the gg-configured donor 24 is more β-selective toward adamantanol than the gt conformer 26 (Table 1, entries 3 and 6). This can be understood in terms of an unfavorable steric interaction between the bulky incoming acceptor and the equatorial methyl ether at the 6-position of the donor in the transition state for β-glycoside synthesis that disfavors β-glycoside formation in the gt series. That such an interaction is possible, and more important than the comparable interaction with the axial methoxy group at the 6-position in reactions with the gg configured donor, is readily ascertained with nuclear Overhauser effect measurements on the products (Figure 6). Thus, the adamantanyl βglycosides 44β and 50β, with their equatorial methoxy and methyl groups respectively at the 6-position both show nOe effects between the C6 substituent and the aglycone. Conversely, no such effect is seen in the diastereomers 41β and 47β in which the respective methoxy and methyl groups are axial (Figure 6). Presumably in the tg configured donor 34 the maximized electron-withdrawing effect of the C6-O6 bond antiperiplanar to the C5-O5 bond shifts the equilibrium between the ion pairs and the covalent donor (Scheme 5) such that contributions from the oxocarbenium ion to the outcome of the glycosylation are minimized. This leads to a more SN2-like transition state in which the influence of the steric clash between the incoming acceptor and the equatorial group at C6 is reduced.

Figure 6.

Nuclear Overhauser correlations in the β-adamantanyl glycosides suggestive of retarded β-glycoside formation in the gt configured systems.

A second partial exception to the overall rule is found in our work on the influence of side chain configuration on the reactivity and selectivity of the 4-O-,5-N-oxazolidinone-protected sialyl donors.[4f] Here the donor with the 7S configuration was found by NMR spectroscopy to adopt the gg conformation about the exocyclic bond (C6–C7 in the sialic acids) and to be more reactive than the 7R-epimer in which the gt conformation predominates (Figure 7). Thus, reactivity-wise the general pattern is followed with the diastereomer that adopts the gg-conformation being more reactive. However, the more reactive 7S-epimer with its gg conformation was found to be more equatorially selective than the 7R isomer with the gt conformation of the side chain. This is because the side chain of the sialic acids is considerably larger than the methoxy and methyl substituents in the donors studied here and in the 7R-isomer significantly shields the one face of the donor.

Figure 7.

Structure of the 7S (gg) and 7R (gt) isomers of an N-acetyloxazolidinone protected sialyl donor and their relative reactivities and selectivities.

Conclusions

A series of bicyclic conformationally constrained mannopyranosyl donors carrying either axial or equatorial methoxy or methyl groups at the 6-position has been synthesized and the influence of the substituent on the stereoselectivity of glycosylation reactions studied. An axial methoxy group at the 6-position is found to result in a decrease in selectivity for formation of the equatorial (β-) glycoside whereas an axial methyl group has little consequence on selectivity. This result is discussed in the context of other literature examples and is interpreted in terms of stabilization of the transient glycosyl oxocarbenium ion by the axial C6-OMe bond, which increases the population of the oxocarbenium ion and its ion pairs respective to the covalent donor and so results in a greater proportion of SN1-like reactivity and selectivity. Exceptions to generally emerging rule of the influence of the conformation of the side chains of glycosyl donors on reactivity and especially selectivity are discussed and understood in the layering of pervading steric effects on top of the basic stereoelectronic principle. Extending the general concept we anticipate that monocyclic glycosyl donors in which the population of the gg conformer of the side chain is enhanced by the protecting group array at other positions will show more oxocarbenium-like character in both their reactivity and selectivity.

Experimental Section

Experimental Details.

1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution unless otherwise stated at 400, 500, or 600 MHz. 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution unless otherwise stated at 100, 125, or 150 MHz. Mass spectra were recorded in the +ve ion mode using electrospray ionization (ESI-TOF). Specific rotations were recorded in dichloromethane solution at room temperature unless otherwise stated. Molecular sieves used in glycosylation reactions were of the commercial. All reaction solvents were dried by standing over molecular sieves.

Phenyl 4,8-anhydro-7-deoxy-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-d-glycero-α-d-thio-mannooctopyranoside (24)

To a stirred solution of diol 23 (0.75 g, 2.09 mmol) in pyridine (6 ml) was added tosyl chloride (0.52 g, 2.72 mmol) and DMAP (25 mg, 0.20 mmol) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 hour before TLC (60% ethyl acetate in hexane) showed reaction completion. The solvents were evaporated, washed with 1N hydrochloric acid, extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 20 ml), and dried over Na2SO4. The combined extracts were concentrated under high vacuum and the crude residue was taken for further step without purification. To the crude tosylate was then added DMF (6 ml) and NaH (0.42 g, 10.4 mmol) at 0 °C. This reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min before TLC (20% ethyl acetate in hexane) showed reaction completion. The mixture was washed with water, extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 20 ml), and dried over Na2SO4. Combined extracts were evaporated under high vacuum and silica gel column chromatography afforded 24 (0.37 g, 52% over two steps) as a colorless oil. Rf=0.60 (hexane/EtOAc 4:6); [α]D22 = +162.2 (c 0.17, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.48 – 7.46 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.33 – 7.23 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 5.74 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.10 (t, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.02 (dd, J = 9.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-5), 3.88 (dd, J = 2.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.79 – 3.74 (m, 2H, H-8, H-8′), 3.69 (dd, J = 2.4, 5.8 Hz, 1H, H-6), 3.51 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.51 – 3.49 (m, 1H, H-3), 3.48 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.42 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.01 – 1.94 (m, 1H, H-7), 1.83 – 1.71 (m, 1H, H-7′); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 134.9, 130.5, 129.0, 127.1, 85.7, 79.3, 78.9, 74.0, 72.3, 72.1, 62.4, 58.6, 57.6, 57.1, 29.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C17H24O5SNa [M+Na]+, 363.1242; found, 363.1241.

Phenyl 4,8-anhydro-7-deoxy-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-l-glycero-α-d-thio-mannooctopyranoside (26)

Compound 26 (61%, 0.43 g) was synthesized analogously as 24 from compound 25, as a white solid. Rf= 0.40 (hexane/EtOAc 4:6); m.p. 103 – 106 °C; [α]D22 = +119.7 (c 0.75, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.57 – 7.55 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.32 – 7.26 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 5.74 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.05 – 4.03 (m, 1H, H-8), 4.05 (dd, J = 8.8, 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 3.87 (dd, J = 2.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.55 (dd, J = 3.4, 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.54 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-4), 3.50 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.49 – 3.48 (m, 1H, H-6), 3.48 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.45 – 3.41 (m, 1H, H-8′), 3.36 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.03 (dd, J = 13.2, 5.1 Hz, 1H, H-7), 1.73 – 1.62 (m, 1H, H-7′); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.8, 132.4, 129.0, 127.8, 85.5, 78.8, 78.7, 78.0, 76.7, 74.6, 66.2, 58.6, 58.1, 57.9, 31.8; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C17H24O5SNa [M+Na]+, 363.1242; found, 363.1243.

Phenyl 7-deoxy-4,6-O-benzylidene-2,3-di-O-methyl-d-glycero-α-d-thio-mannoheptopyranoside (34)

To a solution of diol 32 (0.2 g, 0.63 mmol) and CSA (0.78 g, 0.06 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (8 ml) was added benzaldehyde dimethyl acetal (0.37 ml, 2.54 mmol) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 6 h at room temperature before TLC analysis (20% ethyl acetate in hexane) showed the reaction completion. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2, washed with aqueous saturated NaHCO3. The aqueous solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 ml), combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The crude residue was purified through silica gel column chromatography to afford 34 in 80% (0.20 g) yield as a white solid. Rf= 0.60 (hexane/EtOAc 4:1); m.p. 112 – 113 °C; [α]D22 = +193.7 (c 1.45, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.53 – 7.49 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.39 – 7.29 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 5.68 (s, 1H, Benzylidene-H), 5.67 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.15 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.04 – 3.91 (m, 1H, H-6), 3.91 (dd, J = 3.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.88 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 3.72 (dd, J = 10.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.59 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.54 (s, 3H, OCH3), 1.24 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 3H, H-7); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.6, 133.8, 131.5, 129.1, 128.8, 128.2, 127.6, 126.2, 101.1, 85.6, 80.2, 78.4, 76.7, 75.1, 70.8, 59.1, 59.0, 17.7; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C22H26O5SNa [M+Na]+, 425.1399; found, 425.1391.

Phenyl 7-deoxy-4,6-O-benzylidene-2,3-di-O-methyl-l-glycero-α-d-thio-mannoheptopyranoside (35)

Compound 35 (0.15 g, 61%) was synthesized analogously as 34 from compound 33, as a white solid. Rf= 0.50 (hexane/EtOAc 4:1); m.p. 92 – 93 °C ; [α]D22 = +201.0 (c 0.40, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 – 7.47 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.39 – 7.28 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 5.89 (s, 1H, Benzylidene-H), 5.64 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.53 (dd, J = 10.1, 5.7 Hz, 1H, H-5), 4.46 – 4.41 (m, 1H, H-6), 4.37 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H, H-4), 3.90 (dd, J = 3.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.70 (dd, J = 9.6, 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 3.58 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.52 (s, 3H, OCH3), 1.48 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, H-7); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.9, 134.1, 131.5, 129.1, 128.8, 128.2, 127.6, 126.2, 94.3, 85.9, 80.2, 78.5, 72.8, 70.4, 67.3, 59.1, 58.8, 11.8; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C22H26O5SNa [M+Na]+, 425.1399; found, 425.1401.

General Procedure for Glycosylation Reaction

A stirred solution of glycosyl donor (0.1 mmol), BSP (1.0 equiv.), TTBP (2.0 equiv.) and 4Å Molecular sieves (34 mg) in CH2Cl2 (2.6 ml) was kept for 1 h at room temperature. Then, freshly distilled Tf2O (1.1 equiv.) was added at −78 °C (Benzylidene protected glycosyl donors 34 and 35 were activated at −60 °C). After 1 h, a solution of the glycosyl acceptor (1.5 equiv.) in dichloromethane (1.0 ml) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 20 min (reaction completed in 3 h when benzylidene protected donors 34 and 35 were used) before it was quenched with sat. NaHCO3 (1.0 ml) solution. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 ml), washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution (10 ml), brine (5 ml), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The glycosides were isolated using silica gel column chromatography (eluent: ethyl acetate in hexane).

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Glycosyl Acceptors 36, 37, and 38.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM62160) for support of this work, and acknowledge support from the NSF (MRI-084043) for the purchase of the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer in the Lumigen Instrument Center at Wayne State University.

References

- 1.a) Bock K, Duus JO. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1994;13:513–543. [Google Scholar]; b) Grindley TB. In: Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Fraser-Reid B, Tatsuta K, Thiem J, editors. Vol. 1. Berlin: Springer; 2001. pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]; c) Rao VSR, Qasba PK, Balaji PV, Chandrasekaran R. Conformation of Carbohydrates. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]; d) Tvaroska I, Taravel FR, Utille JP, Carver JP. Carbohydr. Res. 2002;337:353–367. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(01)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Padrón JI, Morales EQ, Vázquez JT. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:8247–8258. [Google Scholar]; b) Morales EQ, Padron JI, Trujillo M, Vázquez JT. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:2537–2548. [Google Scholar]; c) Roën A, Mayato C, Padron JI, Vázquez JT. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7266–7279. doi: 10.1021/jo801184q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Roën A, Padrón JI, Mayato C, Vázquez JT. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3351–3363. doi: 10.1021/jo800191z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Nobrega C, Vázquez JT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:2793–2801. [Google Scholar]; f) Mayato C, Dorta RL, Vázquez JT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:931–948. [Google Scholar]; g) Mayato C, Dorta RL, Vázquez JT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:2385–2397. [Google Scholar]; h) Roën A, Padron JI, Vázquez JT. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4615–4630. doi: 10.1021/jo026913o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Sanhueza CA, Dorta RL, Vázquez JT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:258–264. [Google Scholar]; j) Mayato C, Dorta RL, Vázquez JT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:2803–2811. [Google Scholar]; k) Padrón JI, Vázquez JT. Chirality. 1997:626–637. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen HH, Nordstrom M, Bols M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9205–9213. doi: 10.1021/ja047578j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Bohé L, Crich D. CR Chimie. 2011;14:3–16. [Google Scholar]; b) Bohé L, Crich D. Carbohydr. Res. 2015;403:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Satoh H, Manabe S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:4297–4309. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35457a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Litjens REJN, van den Bos LJ, Codée JDC, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel G. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Dinkelaar J, de Jong AR, van Meer R, Somers M, Lodder G, Overkleeft HS, Codée JDC, van der Marel GA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4982–4991. doi: 10.1021/jo900662v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kancharla PK, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18999–19007. doi: 10.1021/ja410683y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Moumé-Pymbock M, Furukawa T, Mondal S, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14249–14255. doi: 10.1021/ja405588x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Fraser-Reid B, Wu ZC, Andrews W, Skowronski E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:1434–1435. [Google Scholar]; b) Andrews CW, Rodebaugh R, Fraser-Reid B. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:5280–5289. doi: 10.1021/jo961115h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Douglas NL, Ley SV, Lucking U, Warriner SL. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1998;1:51–65. [Google Scholar]; b) Koeller KM, Wong CH. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4465–4493. doi: 10.1021/cr990297n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang MT, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:545–553. doi: 10.1021/jo8017846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Smith DM, Woerpel KA. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:1195–1201. doi: 10.1039/b600056h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jensen HH, Bols M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:259–265. doi: 10.1021/ar050189p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Heuckendorff M, Pedersen CM, Bols M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:13982–13994. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Garcia A, L. Otte DA, Salamant WA, Sanzone JR, Woerpel KA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:3061–3064. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Miljkovic M, Yeagley D, Deslongchamps P, Dory YL. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7597–7604. [Google Scholar]; f) Garcia A, Otte DAL, Salamant WA, Sanzone JR, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:4470–4480. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balmond EI, Benito-Alifonso D, Coe DM, Alder RW, McGarrigle EM, Galan MC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:8190–8194. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Huang M, Tran H-A, Bohé L, Crich D. In: Carbohydrate Chemistry: Proven Synthetic Methods. van der Marel GA, Codée JDC, editors. Vol. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014. pp. 175–181. [Google Scholar]; b) Chevalier R, Esnault J, Vandewalle P, Sendid B, Colombel J-F, Poulain D, Mallet J-M. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7669–7677. [Google Scholar]; c) Tetsuta O, Masahiro T, Susuma K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:6493–6496. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shie C-R, Tzeng Z-H, Wang C-C, Hung S-C. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2009;56:510–523. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dess PB, Martin JC. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson R, Samuelsson B. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1984;1:2371–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes DL. Org. React. 1992;42:335–656. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Oikawa Y, Yoshioka T, Yonemitsu O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;28:889–892. [Google Scholar]; b) Lergenmuller M, Nukada T, Kuramochi K, Dan A, Ogawa T, Ito Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999:1367–1376. [Google Scholar]; c) Crich D, Banerjee A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1935–1938. doi: 10.1021/ol050224s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Crich D, Banerjee A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8078–8086. doi: 10.1021/ja061594u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crich D, Smith M, Yao Q, Picione J. Synthesis. 2001:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crich D, Smith M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9015–9020. doi: 10.1021/ja0111481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crich D, Sun S. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:8321–8348. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Bock K, Pedersen C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1974;2:293–297. [Google Scholar]; b) Tvaroska I, Taravel FR. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1995;51:15–61. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Booth H, Everett JR. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1980;2:255–259. [Google Scholar]; b) Jensen FR, Bushweller CH, Beck BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:344–351. [Google Scholar]; c) Jensen FR, Bushweller CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:3223–3225. [Google Scholar]; d) Jensen FR, Bushweller CH. Adv. Alicycl. Chem. 1971;3:139–194. [Google Scholar]; e) Schneider H-J, Hoppen V. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:3866–3873. [Google Scholar]; f) Höfner D, Lesko SA, Binsch G. Org. Magn. Res. 1978;11:179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin A, Arda A, Désiré J, Martin-Mingot A, Probst N, Sinaÿ P, Jiménez-Barbero J, Thibaudeau S, Blériot Y. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:141–188. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Crich D, Sun S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11217–11223. [Google Scholar]; b) Frihed TG, Bols M, Pedersen CM. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:4963–5013. doi: 10.1021/cr500434x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Crich D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1144–1153. doi: 10.1021/ar100035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crich D. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:9193–9209. doi: 10.1021/jo2017026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Aubry S, Sasaki K, Sharma I, Crich D. Top. Curr. Chem. 2011;301:141–188. doi: 10.1007/128_2010_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang M, Garrett GE, Birlirakis N, Bohé L, Pratt DA, Crich D. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:663–667. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Huang M, Retailleau P, Bohé L, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14746–14749. doi: 10.1021/ja307266n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Adero PO, Furukawa T, Huang M, Mukherjee D, Retailleau P, Bohé L, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10336–10345. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crich D, Cai W, Dai Z. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:1291–1297. doi: 10.1021/jo9910482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Bols M, Liang X, Jensen HH. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:8970–8974. doi: 10.1021/jo0205356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jensen HH, Bols M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3419–3421. doi: 10.1021/ol030081e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bülow A, Meyer T, Olszewski TK, Bols M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods RJ, Andrews CW, Bowen JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:859–864. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.