Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between current substance use and unhealthy weight loss practices (UWLP) among 12-to-18 year olds.

Methods

Participants were 12-to-18 year olds who completed the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey in Florida (N=5,620). Current alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use was self-reported based on last 30-day use. UWLP was defined based on self-report of at least one of three methods to lose weight in last 30-days: 1) ≥ 24 hours of fasting, 2) diet pill use, and 3) laxative use/purging. The reference group included those with no reported UWLP. Logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, academic performance, age-sex-specific body mass index percentiles, and perceived weight status were fitted to assess relationships between UWLP and current substance use.

Results

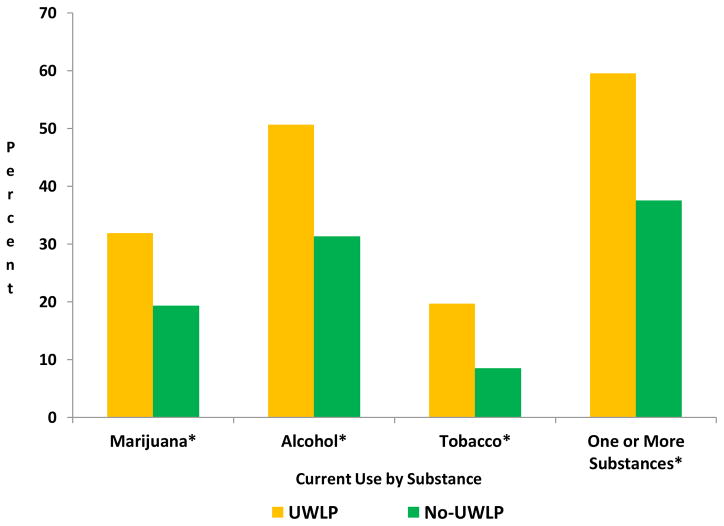

About 15% and 41% of adolescents reported ≥ 1 UWLP and use of ≥1 substance in the last 30-days, respectively. Over half (60.1%) of adolescents who reported substance use engaged in UWLP (p<0.0001). The prevalence of current alcohol use (50.6%) was the highest among those who reported UWLP, followed by marijuana (31.9%), tobacco (19.7%), and cocaine (10.5%) use. Adolescents who reported current tobacco (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] =2.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.1–3.6), alcohol (AOR=2.2, 95% CI=1.9–2.6), or marijuana (AOR=2.1, 95% CI=1.7–2.5) use had significantly higher odds of UWLP compared to their non-user counterparts.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study shows that substance use and UWLP behaviors are likely to co-exist in adolescents. Further studies are necessary to determine the temporal relationship between substance use and UWLP. It is recommended that intervention programs for youth consider targeting these multiple health risk behaviors.

Significance

It is generally speculated that health risk behaviors co-exist in adolescence; however, gaps in knowledge remain. Specifically, while other studies may have broached relationships between substance use and UWLP, marijuana use, perceived weight status, and at times BMI percentiles were not included simultaneously along with alcohol and cigarette use. Considering the highest obesity prevalence among adolescents are among southern states, our study adds to the literature by describing substance use and UWLP patterns among adolescents in Florida. Our findings add evidence to the literature to suggest future prevention and intervention programs consider targeting multiple risk factors.

Keywords: substance use, adolescence, YRBS, CDC, unhealthy weight loss

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a developmental period when health risk behaviors (e.g., unhealthy eating and substance use behaviors) that may continue into adulthood are established (Dietz, 1998). The majority (66.2%) of 9th–12th graders in the United States (US), for example, report consuming alcohol in their lifetime (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014b). Marijuana and tobacco use initiation is also prevalent in about 40% of 9th–12th graders in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014c, 2014d). According to the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, current use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana was prevalent among was 15.7%, 34.9%, and 23.4% of 9th–12th graders, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014b, 2014c, 2014d). Although substance use remains prevalent across the nation, current substance use prevalence in the South was reported to be higher than the national average in all categories except illicit drug use in 2013 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

Concurrent with high proportions of substance use, overweight and obesity status among adolescents in the US is high. Previous studies have noted a four-fold increase (5% to 21%) of overweight and obesity status in adolescents within the last 30 years (Duan, 2014; National Center for Health Statistics, 2012; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2013). In 2013, 7 of the 10 states with the highest obesity rates among 10-to-17 year olds were in the South (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2014). These statistics are important to consider in context of the overall economic and public health burden of substance use and obesity. The public health burden of obesity is clear in that obese adolescents are more likely to present with cardiovascular disease risk, type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, bone issues, and psychological problems such as eating disorders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a; Freedman, Dietz, Srinivasan, & Berenson, 2009; Sutherland, 2008).

Adolescence has also been documented as the developmental period with the highest risk for the emergence of eating disorders and associated weight-related behaviors (Martinsen & Sundgot-Borgen, 2013; Patton, Selzer, Coffey, Carlin, & Wolfe, 1999; Rohde, Stice, & Marti, 2014). Unhealthy weight control behaviors and unhealthy weight loss practices (UWLP) (defined as ≥ 24 hours of fasting, diet pill use, laxative use, or purging) have also been identified in adolescence (Haines, Kleinman, Rifas-Shiman, Field, & Austin, 2010). Moreover, substance use has been linked to disordered eating in middle (Garry, 2002) and high school students (Antin & Paschall, 2011; Eichen, Conner, Daly, & Fauber, 2012; Pasch et al., 2011). Current literature is scarce in documenting the relationship between recent substance use and UWLP among adolescents, especially those residing in the South. Considering the prevalence of obesity and substance use in this geographical region of the US, authors sought to examine the relationship between substance use and UWLP.

The primary aims of this study were to (1) estimate the prevalence of current UWLP and current substance use (alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana); and (2) examine the relationship between current substance use and UWLP among a representative sample of 12-to-18 year old high school students using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) of Florida.

METHODS

Study Population

The source population was 12-to-18 year old students (N=6,089) who completed the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) collected from Florida high schools in 2013. Students with missing data for UWLP (n=98), marijuana use (n=200), alcohol use (n=121), or cigarette use (n=50) were excluded. Missing data in key variables was less than 5% of the sample and sensitivity analyses confirmed no significant differences between those with missing data and those with complete data. Thus, analyses are based on 5,620 students. The YRBS is a survey administered to public high school students in the Spring or Fall semesters of odd-numbered years by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b). The survey uses a two-staged, cluster sample design to select a sample representative of 9th through 12th grade students in respective jurisdictions (N. Brener et al., 2013). The CDC’s Institutional Review Board provided approval for the national YRBS (L. Kann et al., 2014).

Details of survey administration are described elsewhere (N. Brener et al., 2013); in brief, parents provided passive consent by signing a form only if they did not want their child to participate. Once consent was determined, computer-scannable questionnaires were completed by the student in class at an arranged date and time. To increase response rates and representativeness of Florida high school students, alternative questionnaire administration dates were offered to students absent or unable to complete the questionnaire on the arranged date and time. Privacy during questionnaire completion was ensured by employing in-class strategies to minimize the possibility of students seeing each other’s responses. Completed questionnaire booklets were sealed and placed in an unmarked envelope at the end of administration to further protect response privacy (N. Brener et al., 2013).

Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice (UWLP)

Responses from the following questions were used to define UWLP: (1) “During the past 30 days, did you go without eating for 24 hours or more (also called fasting) to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?”; (2) “During the past 30 days, did you take any diet pills, powders, or liquids without a doctor’s advice to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight? (Do not include meal replacement products such as Slim Fast.)”; (3) “During the past 30 days, did you vomit or take laxatives to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?”(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). The reference group was defined as students who reported none of the aforementioned methods to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight.

Substance Use

Individual substance use categories for current marijuana, alcohol, and cigarette use were defined using the following questions in the YRBS: (1) “During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana?”; (2) “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?”; and (3) “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?”. Marijuana, alcohol, and cigarette use were treated as individual binary variables (1=use in any day or any number of times used in past 30 days, 0=no use at all in past 30 days) in the analyses. Categories were dichotomized for analysis purposes to mirror UWLP questions.

Covariates

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, academic performance, perceived weight status, and age-sex-specific body mass index (BMI) percentiles were considered covariates a priori. The YRBS captured age as 12 years old or younger, 13-, 14-, 15-, 16-, 17-, and 18 years old or older. The 12 years old or younger and 13 years old categories were combined due to the low frequency reported for analysis purposes. Gender was recorded as male/female. Race/ethnicity was defined as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander were combined to create an “Other” race/ethnic group. Academic performance was categorized by letter grades: A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s, or F’s.

Perceived weight status was categorized into three groups (underweight, healthy weight, and overweight) from five original response options based on the following question: “How do you describe your weight?” (very underweight, slightly underweight, about the right weight, slightly overweight, and very overweight) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Very underweight and slightly underweight were recoded as “underweight”; about the right weight was recoded as “healthy weight”; and slightly overweight and very overweight were recoded as “overweight”. Age-sex-specific BMI percentiles were obtained based on self-reported height and weight and they were categorized in accordance to CDC guidelines: underweight (>5th percentile), healthy weight (5th to >85th percentile), overweight (85th to >95th percentile), and obese (≤95th percentile) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analytic Software (SAS) version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. Appropriate survey analysis methodology was taken into account by incorporating sampling design, weight, and non-response effects (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014a). Weighted survey frequencies and chi-square tests were used to estimate the differences in prevalence of substance use, UWLP, and covariates between groups. Survey logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, academic performance, age-sex-specific BMI percentiles, and perceived weight status were used to examine relationships between 1) individual unhealthy weight loss practices (UWLP) (≥ 24 hours of fasting, use of diet pills, use of laxatives/purging) and each substance (marijuana, alcohol, cigarettes) use; and 2) engaging in one or more UWLP and each substance (marijuana, alcohol, cigarettes) use. Results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample (N=5,620) represented 736,281 high school students (grades 9–12) in Florida public schools and was evenly split between genders (50.2% female, 49.8% male). Overall, there were more Non-Hispanic White students (43.7%) than Non-Hispanic Black (22.6%) or Hispanic (27.9%) students. Almost half (45.2%) of the sample reported academic grades of mostly B’s, followed by mostly A’s (31.2%) and mostly C’s (19.8%). The majority of the sample (64.0%) was 16 years of age or older. Over half (56.6%) of the students perceived their weight status to be the “healthy weight” while 64.1% had an actual age-sex-specific BMI percentile within the healthy (5th-to-84.9th percentile) range.

Females represented the majority (67.4%) among those who reported UWLP, while males represented the majority (52.8%) among the No-UWLP group. The prevalence of poor academic performance (Mostly D’s or Mostly F’s) was higher among UWLP than No-UWLP (7.9% vs 3.0%, p<0.0001). Over half (51.5%) of UWLP students perceived their weight status to be overweight compared to only a quarter (25.7%) of those with No-UWLP (p<0.0001). There were more overweight or obese (34.0%) students in the UWLP group compared to the No-UWLP group (22.4%); however, slightly more underweight students were represented in UWLP (12.3%) than in No-UWLP (11.6%). Detailed characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 12-to-18 year olds by Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice (UWLP) (N=5,620)

| All N=5,620 n (%)† |

UWLP n=841 n (%)† |

No-UWLP n=4,779 n (%)† |

p-value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 2,685 (49.8) | 259 (32.6) | 2,426 (52.8) | |

| Female | 2,892 (50.2) | 569 (67.4) | 2,323 (47.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.05 | |||

| White | 2,129 (43.7) | 341 (47.4) | 1,788 (43.0) | |

| Black | 1,097 (22.6) | 141 (19.9) | 956 (23.1) | |

| Hispanic | 1,732 (27.9) | 249 (26.6) | 1,483 (28.1) | |

| Other | 538 (5.8) | 85 (6.1) | 453 (5.8) | |

| Age | 0.01 | |||

| 13 years old or younger | 25 (0.50) | 10 (1.2) | 15 (0.30) | |

| 14 years old | 629 (10.9) | 83 (9.7) | 546 (11.2) | |

| 15 years old | 1,433 (24.6) | 227 (25.5) | 1,206 (24.5) | |

| 16 years old | 1,485 (25.5) | 214 (24.8) | 1,271 (25.6) | |

| 17 years old | 1,285 (24.0) | 184 (23.7) | 1,101 (24.0) | |

| 18 years old or older | 747 (14.5) | 117 (15.1) | 630 (14.4) | |

| Academic Performance | <0.0001 | |||

| Mostly A’s | 1,515 (31.2) | 174 (24.6) | 1,341 (32.4) | |

| Mostly B’s | 2,208 (45.2) | 332 (45.9) | 1,876 (45.1) | |

| Mostly C’s | 974 (19.8) | 157 (21.5) | 817 (19.5) | |

| Mostly D’s | 115 (2.3) | 33 (4.2) | 82 (2.0) | |

| Mostly F’s | 66 (1.5) | 26 (3.7) | 40 (1.0) | |

| Perceived Weight Status | <0.0001 | |||

| Underweight | 779 (13.9) | 87 (10.5) | 692 (14.5) | |

| HealthyWeight | 3,157 (56.6) | 320 (38.0) | 2,837 (59.8) | |

| Overweight | 1,661 (29.5) | 431 (51.5) | 1,230 (25.7) | |

| Body Mass Index Percentile | <0.0001 | |||

| < 5th (underweight) | 655 (11.7) | 103 (12.3) | 552 (11.6) | |

| ≥5th and < 85th (healthy weight) | 3,619 (64.1) | 450 (53.5) | 3,169 (65.9) | |

| ≥85th and <95th (overweight) | 773 (13.7) | 163 (19.0) | 610 (12.7) | |

| ≥> 95th (obese) | 573 (10.5) | 125 (15.0) | 448 (9.7) |

Weighted percent

Chi-square test comparing UWLP vs No-UWLP

Prevalence of Unhealthy Weight Loss Behaviors

About 15.0% of the sample reported at least one UWLP. Fasting was the most popular (71.5%) method, followed by the use of diet pills (37.6%), and laxatives (27.5%) among UWLP. Although only 19.0% of students who engaged in UWLP fell within the overweight age-sex specific BMI percentile, over half (51.5%) perceived themselves to be overweight. Among students who reported fasting over 24 hours, 37.6% perceived themselves to be overweight and 26.1% perceived themselves to be the healthy weight. Twenty percent (19.9%) of students who reported the use of diet pills perceived themselves to be overweight and 13.6% perceived themselves to be the healthy weight. Among students who used laxatives, 14.5% perceived themselves to be overweight and only 8.6% perceived themselves to be the healthy weight (p<0.01). (Data not shown)

Perceived Weight Status and Unhealthy Weight Loss Practices

A higher proportion of students who engaged in UWLP perceived themselves to be overweight (51%) despite the fact that the majority (66%) were within the healthy BMI percentile (5th to <85th percentile) for their age and sex. Students who engaged in UWLP had a higher prevalence of being categorized as overweight (21.0%) or obese (16.5%) compared to No-UWLP (13.6% and 10.7%, respectively; both p<0.0001) based on their BMI percentiles. Interestingly, 12.3% of students who engaged in UWLP were underweight (age-sex specific BMI <5th percentile). Only 22.3% of students among the UWLP group who perceived themselves to be underweight were actually underweight (BMI <5th percentile); and 64.2% of the students who perceived themselves to be underweight were actually within the healthy BMI percentile range (5th<BMI <85th percentile). (Data not shown)

Prevalence of Substance Use

One third (34.2%) of the overall sample reported alcohol use, 21.2% reported marijuana use, and 10.1% reported cigarette use, all within the last 30-days (Data not shown). The prevalence of the use of at least one substance in the last 30-days was significantly higher among students who reported UWLP (59.5%) compared to students with No-UWLP (37.5%). Specifically, 32.0% of students who engaged in UWLP reported current marijuana use compared to 19.3% of No-UWLP. Likewise, 50.6% (UWLP) and 31.3% (No-UWLP) reported current alcohol use; and 19.7% (UWLP) and 8.5% (No-UWLP) reported current cigarette use (p<0.0001 for all comparisons) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence† of Current‡ Substance Use among 12-to-18 year olds by Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice.

† Weighted percentages

‡ Current use is defined as use at least once in the last 30-days

* Chi-square test comparing UWLP vs No-UWLP p<0.0001

Table 2 describes the prevalence of each substance among the individual components of UWLP. The prevalence of current substance use was significantly higher among students who engaged in each UWLP (≥ 24 hours of fasting, the use of diet pills, or the use of laxatives/purging) when compared to No-UWLP (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). Significant results from Table 2 are presented below:

Table 2.

Prevalence† of Current Substance Use by Individual Components of Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice among 12-to-18 year olds (N=5,620)

| Marijuana Use (N=1,178) | Alcohol Use (N=1,911) | Cigarette Use (N=563) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 24 Hours of Fasting | |||

| Yes | 31.8% | 48.5% | 18.5% |

| No | 19.9% | 32.5% | 9.1% |

| Use of Diet Pills | |||

| Yes | 35.5% | 58.5% | 27.7% |

| No | 20.3% | 32.7% | 9.1% |

| Use of Laxatives or Purging | |||

| Yes | 35.1% | 58.0% | 29.0% |

| No | 20.6% | 33.2% | 9.3% |

Weighted percentage (prevalence): all comparisons at p<0.0001 based on Chi-Square analyses

Fasting 24 hours or more

Among students who reported ≥ 24 hours of fasting, 31.8% reported current marijuana use compared to 19.9% of those who did not fast; 48.5% consumed alcohol compared to 32.5% who did not fast; 18.5% reported cigarette use compared to 9.1% who did not fast.

Use of Diet Pills

Thirty-five percent of diet pill users reported marijuana use, while only 20% of non-diet pill users reported marijuana use. Likewise, alcohol use was higher among diet pill users (58.5%) than non-diet pill users (32.7%). Cigarette use among diet pill users and non-diet pill users were 27.7% and 9.1%, respectively.

Use of Laxatives or Purging

Among those who reported the use of laxatives/purging, 35.1%, 58.0%, and 29.0% reported use of marijuana, alcohol, and cigarette, respectively. In the comparison group that did not use laxatives/purging, corresponding values were 20.6% (marijuana), 33.2% (alcohol), and 9.3% (cigarette).

Relationship between Substance Use and Unhealthy Weight Loss Practices

Table 3 depicts unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses for each UWLP and substance use category. In general, marijuana users had double the odds of their counterparts to report ≥24 hours of fasting (OR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.55–2.29), the use of diet pills (OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 1.68–2.79), and the use of laxatives/purging (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.60–2.70). Compared to non-users of alcohol, alcohol users had two to three times the odds of ≥24 hours of fasting (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.65–2.32); the use of diet pills (OR: 2.90, 95% CI: 2.27–3.70); and the use of laxatives/purging (OR: 2.78, 95% CI: 2.13–3.62). Compared to non-smoking counterparts, cigarette users had about two to four times the odds of ≥24 hours of fasting (OR: 2.26, 95% CI: 1.72–2.80); the use of diet pills (OR: 3.84, 95% CI: 2.97–4.98), and the use of laxatives/purging (OR: 3.96, 95% CI: 2.99–5.24).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted† Odds of Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice by Current Substance Use Categories among 12-to-18 year olds (N=5,620)

| Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Marijuana Use | Alcohol Use | Cigarette Use | |

| ≥ 24 Hours of Fasting (n=599) | 1.88 (1.55–2.29) | 1.96 (1.65–2.32) | 2.26 (1.72–2.80) |

| Use of Diet Pills (n=316) | 2.17 (1.68–2.79) | 2.90 (2.27–3.70) | 3.84 (2.97–4.98) |

| Use of Laxatives or Purging (n=241) | 2.08 (1.60–2.70) | 2.78 (2.13–3.62) | 3.96 (2.99–5.24) |

| ≥ 1 Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice (n=814) | 1.95 (1.64–2.32) | 2.24 (1.93–2.60) | 2.64 (2.10–3.34) |

|

|

|||

| Adjusted Odds Ratios† | |||

|

|

|||

| ≥ 1 Unhealthy Weight Loss Practice (n=814) | 2.00 (1.68–2.38) | 2.25 (1.89–2.68) | 2.53 (1.85–3.47) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, academic performance, age-sex-specific body mass index percentiles, and perceived weight status.

Current marijuana users were twice as likely to engage in at least one UWLP (AOR: 2.00, 95% CI: 1.68–2.38) than their non-user peers after adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, academic performance, age-sex specific BMI percentile, and perceived weight status. After adjustment of the same variables, current alcohol users were twice as likely as non-alcohol users to engage in at least one UWLP (AOR: 2.25, 95% CI: 1.89–2.68). Similarly, cigarette users had 2.53 (95% CI: 1.85–3.47) times the odds of engaging in at least one UWLP compared to non-smokers. Interactions were tested by age group, gender, race/ethnicity, BMI status, and academic performance. There were no significant findings except by gender among marijuana users (β=−0.51, p=0.003).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that UWLP and current substance use are likely to co-exist among Florida high school students. Specifically, the prevalence of current substance use, regardless of substance (marijuana, alcohol, or cigarettes), was significantly higher among students who reported UWLP compared to students who did not report any UWLP. Furthermore, the prevalence of substance use was higher among students who engaged in ≥ 24 hours of fasting, students who reported the use of diet pills, and students who reported the use of laxatives/purging when compared to students with No-UWLP.

Students in our Florida sample were generally comparable to national (US) 2013 YRBS prevalence estimates of current substance use and UWLP. Specifically, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of current marijuana use and alcohol use. Florida students were less likely to report current cigarette use (10.8%) than students nationwide (15.7%). There were no significant differences between Florida and US students with regard to students who reported the use of diet pills within the last 30-days, or students who took laxatives. Florida students were less likely to report fasting than students nationwide (FL: 10.9% vs 13.0%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014e). Compared to the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014), students in our sample had a higher prevalence of current use of marijuana (FL: 22.0% vs NSDUH: 7.1%) and alcohol (FL: 34.8% vs NSDUH: 20.4%). Florida students had a lower prevalence of current cigarette use (10.8%) compared to the NSDUH sample (22.4%).

Our findings also suggest that students who engage in UWLP are more likely to perceive themselves to be overweight despite the fact that the majority are within the healthy BMI percentile for their age and sex. Although there are studies highlighting the misperception of weight among this age group (N. D. Brener, Eaton, Lowry, & McManus, 2004; Eichen et al., 2012; Pasch et al., 2011; Standley, Sullivan, & Wardle, 2009; Talamayan, Springer, Kelder, Gorospe, & Joye, 2006), hypothesis generating results from the current study may lead to future research examining the relationship between weight perception and actual weight among students who engage in UWLP in Florida.

Previous national studies (Eichen et al., 2012; Pisetsky, Chao, Dierker, May, & Striegel-Moore, 2008) that examined the relationship between substance use and UWLP or disordered eating note similar findings of the current study. For example, Pisetsky et al. (2008) (Pisetsky et al., 2008) used 2005 YRBS US data and found that both males and females who engaged in disordered eating had higher odds of marijuana, alcohol and cigarette use than those with no disordered eating behavior. However, Pisetsky et al. (2008) (Pisetsky et al., 2008) is different in that they did not take into account perceived weight status nor actual BMI percentiles. Furthermore, the current study tested for gender interactions and found significance only among marijuana users (β=−0.51, p=0.003). Using 2007 YRBS data, Eichen et al. (2012) (Eichen et al., 2012) also found that students who engaged in disordered eating were more likely to use substances; however, they did not consider marijuana use. Our study contributes to the literature by examining the co-occurrence of UWLP and substance use in Florida adolescents.

Strengths/Limitations

One of the strengths of the current study is that our sample is a representative sample of Florida high school students. We are able to make inferences on the general Florida high school student population with respect to UWLP and current substance use patterns. Furthermore, the study design of the Florida YRBS is standardized by the CDC across all states in the US. Due to the standardization of questions and administration protocol, we are able to compare Florida students to students in other states/nationwide.

Our study is not without limitations. First, all of the data used in the study are self-report. Biological samples to confirm current substance use would be a better objective marker; however, self-report data is considered a valid and reliable measure of substance use (Shillington & Clapp, 2000). Secondly, the current study is a cross-sectional design which limits the temporal relationship between substance use and UWLP. Future studies may also consider examining the relationship between substance use and UWLP prospectively to establish temporal relationship. Finally, we did not look at this relationship in the context of dietary or physical activity behaviors.

Conclusion

Findings suggest a coexistence of risk behaviors, such as unhealthy weight loss practices and substance use among high school students in Florida. A recent report from the Institute of Medicine (Institute of Medicine, 2009) urges interventions to target multiple behavioral disorders. Based on our findings, current substance use and eating disorder prevention and intervention programs should consider targeting multiple risk factors since they may coexist.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH/NIDA grant K01 DA 026993.

Footnotes

No Conflicts of Interest to Report

All work originated from the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Divisions of Epidemiology and Population Health Sciences, Pediatric Clinical Research, Prevention Science, and Biostatistics.

Contributor Information

Denise C. Vidot, Email: dvidot@med.miami.edu.

Sarah E. Messiah, Email: SMessiah@med.miami.edu.

Guillermo Prado, Email: GPrado@med.miami.edu.

WayWay M. Hlaing, Email: WHlaing@med.miami.edu.

References

- Antin TM, Paschall MJ. Weight perception, weight change intentions, and alcohol use among young adults. Body Image. 2011;8(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener N, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kichen S, Eaton D, Hawkins J, Flint KH. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(1):18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Eaton DK, Lowry R, McManus T. The association between weight perception and BMI among high school students. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1866–1874. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About BMI for Children and Teens. 2014 Jul 11; 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent and School Health. Childhood Obesity Facts. 2011 Dec; 2012a. Retrieved July 1, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/obesity/facts.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide to Conducting Your Own Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2012b Retrieved April 16, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/yrbs_conducting_your_own.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 State and Local Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Software for Analysis of YRBS Data. 2014a Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/YRBS_analysis_software.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Alcohol Use National YRBS: 1991–2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014b. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Marijuana, Cocaine, and Other Illegal Drug Use National YRBS: 1991–2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014c. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use National YRBS: 1991–2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Prevention and Control; 2014d. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Online: High School YRBS Florida 2013 and United States 2013 Results. 2014e Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?TT=G&OUT=0&SID=HS&QID=QQ&LID=FL&YID=2013&LID2=XX&YID2=2013&COL=T&ROW1=N&ROW2=N&HT=QQ&LCT=LL&FS=S1&FR=R1&FG=G1&FSL=S1&FRL=R1&FGL=G1&PV=&TST=True&C1=FL2013&C2=XX2013&QP=G&DP=1&VA=CI&CS=Y&SYID=&EYID=&SC=DEFAULT&SO=ASC.

- Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youthL Childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(Supplement 2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan R, Vidot DC, Hlaing WH. Weight loss practice by weight status among adolescents. A Journal of Publich Health and Epidemiology. 2014;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Eichen DM, Conner BT, Daly BP, Fauber RL. Weight perception, substance use, and disordered eating behaviors: comparing normal weight and overweight high-school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Risk factors and adult body mass index among overweight children: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):750–757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry JM, Morrissey SL, Whetstone LM. Substance use and weight loss tactics among middle school youth. Wiley InterScience. 2002 doi: 10.1002/eat.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Austin SB. Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(4):336–343. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Report Brief for Researchers. Washington, DC: 2009. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilites. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance- United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2014;63(SS04):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen M, Sundgot-Borgen J. Higher prevalence of eating disorders among adolescent elite athletes than controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(6):1188–1197. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318281a939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With Special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus11.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(131):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Klein EG, Laska MN, Velazquez CE, Moe SG, Lytle LA. Weight misperception and health risk behaviors among early adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(6):797–806. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.6.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: population based cohort study over 3 years. BMJ. 1999;318(7186):765–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7186.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisetsky EM, Chao YM, Dierker LC, May AM, Striegel-Moore RH. Disordered eating and substance use in high-school students: results from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(5):464–470. doi: 10.1002/eat.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The State of Obesity: Fast facts on the state of obesity in America. 2014 Retrieved November 1, 2014, from http://www.stateofobesity.org/fastfacts.

- Rohde P, Stice E, Marti CN. Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: Implications for prevention efforts. Int J Eat Disord. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eat.22270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Self-report stability of adolescent substance useL are there differences for gender, ethnicity and age? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley R, Sullivan V, Wardle J. Self-perceived weight in adolescents: overestimation or under-estimation? Body Image. 2009;6(1):56–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. NSDUH Series H-48. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland ER. Obesity and asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28(3):589–602. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talamayan KS, Springer AE, Kelder SH, Gorospe EC, Joye KA. Prevalence of overweight misperception and weight control behaviors among normal weight adolescents in the United States. Scientific World Journal. 2006;6:365–373. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]