Abstract

A literature review was undertaken by analyzing distinguished books, undergraduate and postgraduate theses, and peer-reviewed scientific articles and by consulting worldwide accepted scientific databases, such as SCOPUS, Web of Science, SCIELO, Medline, and Google Scholar. Medicinal plants used as immunostimulants were classified into two categories: (1) plants with pharmacological studies and (2) plants without pharmacological research. Medicinal plants with pharmacological studies of their immunostimulatory properties were subclassified into four groups as follows: (a) plant extracts evaluated for in vitro effects, (b) plant extracts with documented in vivo effects, (c) active compounds tested on in vitro studies, and (d) active compounds assayed in animal models. Pharmacological studies have been conducted on 29 of the plants, including extracts and compounds, whereas 75 plants lack pharmacological studies regarding their immunostimulatory activity. Medicinal plants were experimentally studied in vitro (19 plants) and in vivo (8 plants). A total of 12 compounds isolated from medicinal plants used as immunostimulants have been tested using in vitro (11 compounds) and in vivo (2 compounds) assays. This review clearly indicates the need to perform scientific studies with medicinal flora from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, to obtain new immunostimulatory agents.

1. Introduction

The immune system is a complex organization of leukocytes, antibodies, and blood factors that protect the body against pathogens [1]. Innate immunity consists of cells such as lymphocytes, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, which are the first line of host defence [2, 3]. The NK cells lyse pathogens and tumor cells without prior sensitization [4]. Activated macrophages defend the host by phagocytosis, releasing the enzyme lysosomal acid phosphatase, and through the synthesis and release of nitrous oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [5, 6]. These two components inhibit the mitochondrial respiration and the DNA replication of pathogens and cancer cells [7]. When an infection occurs, macrophages and mast cells immediately release interleukins [2]. The interleukins link the communication between cells of the immune system, facilitating innate immune reactions. Among these cytokines, IL-2 and IL-6 induce the stimulation of cytotoxic T cells and enhance the cytolytic activity of NK cells [8, 9]. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), mainly produced by NK cells, exerts antitumor and antiviral effects, increases antigen presentation and lysosomal activity of macrophages, and promotes the cytotoxic effect of NK cells [10].

Immunodeficiency occurs when there is a loss in the number or function of the immune cells, which might lead to infections and diseases such as cancer [11, 12]. Therefore, the discovery of agents which enhance the immune system represents an attractive alternative to the inhibition of tumor growth and the prevention and treatment of some infections. An immunostimulatory agent is responsible for strengthening the resistance of the body against pathogens. In preclinical and clinical studies, some immunostimulatory medicinal plants (e.g., Viscum album and Echinacea purpurea) have increased the immune responsiveness by activating immune cells [3, 11].

In ancient traditional medicine, the term immunostimulant was unknown. In some cases, medicinal plants species that “purify the blood,” “strengthen the body,” and “increase the body's defences” have been used as immunostimulant agents [13, 14].

Some of the in vitro and in vivo tests used to evaluate the immunostimulatory effects of plant extracts and compounds include the following: (a) proliferation of splenocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes, (b) phagocytosis, (c) pinocytosis, (d) production of NO and/or H2O2, (e) NK cell activity, (f) release of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, and other interleukins, and (g) lysosomal enzyme activity. In vivo studies mainly consist in the induction of an immunosuppressed state in the animals by using (a) chemical agents such as 5-fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, and methotrexate or (b) biological agents such as tumorigenic cells. All the above-mentioned agents have been extensively studied on inducing immunosuppression [15, 16].

This review provides ethnomedicinal, phytochemical, and pharmacological information about plants and their active compounds used as immunostimulants in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. This information will be useful for developing preclinical and clinical studies with the plants cited in this review.

2. Methodology

A literature search was conducted from December 2014 to July 2015 by analyzing the published scientific material on native medicinal flora from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Academic information from the last five decades that describes the ethnobotanical, pharmacological, and chemical characterization of medicinal plants used as immunostimulants was gathered. The following keywords were used to search for the academic information: plant extract, plant compound, immune system, immunostimulant, immunostimulatory, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. No restrictions regarding the language of publication were imposed, but the most relevant studies were published in Spanish and English. The criteria for the selection of reports in this review were as follows: (i) plants native to Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, (ii) plants used in traditional medicine as immunostimulants with or without pharmacological evidence, and (iii) plants and their active compounds with information obtained from a clear source. The immunostimulatory activity of plant extracts or compounds in combination with a known immunostimulant agent (such as lipopolysaccharide, CD3) was omitted in this review.

Medicinal plants used as immunostimulants were classified into two categories: (1) plants with pharmacological studies and (2) plants without pharmacological research. The information on medicinal plants with pharmacological studies was obtained from peer-reviewed articles by consulting the academic databases SCOPUS, Web of Science, SCIELO, Medline, and Google Scholar. Medicinal plants with pharmacological studies of their immunostimulatory properties were subclassified into four groups: (a) plant extracts that have been evaluated for in vitro effects, (b) plant extracts with documented in vivo effects, (c) active compounds tested using in vitro studies, and (d) active compounds that have been assayed in animal models. The information for medicinal plants without pharmacological research was obtained from both undergraduate and postgraduate theses, in addition to peer-reviewed articles, and scientific books.

3. Medicinal Plants from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Used as Immunostimulants

We documented 104 plant species belonging to 55 families that have been used as immunostimulants. Of these plants, 28 have pharmacological studies (Table 1), and 76 plants lacked pharmacological research regarding their immunostimulatory activity (Table 6). All plant names and their distributions were confirmed by consulting the Missouri botanical garden (http://www.tropicos.org/). Asteraceae (11 plant species), Fabaceae (8 plant species), and Euphorbiaceae (7 plant species) are the plant families most often used as immunostimulants, including plants with and without pharmacological studies (Tables 1 and 6). We found that 46% of plants used as immunostimulants, with or without pharmacological studies, are also used for the empirical treatment of cancer. This was confirmed, for many plant species, by consulting our previous work [94]. Therefore, we highly recommend evaluating the immunostimulatory effects of medicinal plants used for cancer treatment. Medicinal plants used as immunostimulants are also used for the treatment of diarrhea (23%), cough (18%), and inflammation (18%). Diarrhea and cough are two symptoms associated with gastrointestinal and respiratory infections, respectively. We may therefore infer that immunostimulatory plants may also be used for the treatment and prevention of infections. Medicinal plants used as an antiparasitic agent may treat diseases such as malaria, whereas plants used as antivirals may treat diseases such as measles, smallpox, and others (Tables 1 and 6).

Table 1.

Medicinal plants with pharmacological evidence of their immunostimulant effects.

| Family | Scientific name | Common name | Plant part | Other popular uses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Carlowrightia cordifolia A. Gray | Arnica | Lv | AI | [17] |

| Justicia spicigera Schltdl. | Muicle | Lv | DB, CA | [18] | |

| Anacardiaceae | Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl. | Cuachalalate | Bk | SA, DG, CA | [19] |

| Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | Aceitilla | Wp | DB, DI, SA, CA | [20] |

| Psacalium peltatum (Kunth) Cass. | Matarique | Rt | WH, BP, CA | [21] | |

| Tridax procumbens L. | Ghamra | Ap | WH | [22] | |

| Xanthium strumarium L. | Guizazo de caballo | Rt | DU, CA | [23] | |

| Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia chrysantha (Jacq.) G. Nicholson | Guayacan | Bk | AI, DB, SA | [24] |

| Cactaceae | Lophocereus schottii (Engelm.) Britton & Rose | Garambullo | Sm | CO, DB, SA, CA | [25] |

| Lophophora williamsii (Lem. ex Salm-Dyck) J. M. Coult. | Peyote | Tb | BP, CA | [26] | |

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Papaya | Fr | SA, DG, DI, CA | [27] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia cotinifolia L. | Palito lechero | Latex | AI | [28] |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | Tártago de jardín | Ap | AV | [29] | |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima Willd. ex Klotzsch | Nochebuena | Ap | AI, CO, FL, CA | [28] | |

| Hura crepitans L. | Ceiba | Lv | AI | [28] | |

| Fabaceae | Hymenaea courbaril L. | Guapinol | Bk | DU, AP | [30] |

| Mucuna urens (L.) Medik. | Tortera | Bk | DU | [31] | |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. | Frijol | Sd | DI, BP | [32] | |

| Hypericaceae | Hypericum perforatum L. | Hierba de San Juan | Wp | DP, WH | [33] |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | Aguacate | Lv | AH, BP, WH, CA | [34] |

| Molluginaceae | Mollugo verticillata L. | Hierba de la arena | Ap | AI | [35] |

| Nyctaginaceae | Bougainvillea × buttiana Holttum & Standl. | Bugambilia | Fw | SA, CO | [36] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus niruri L. | Chancapiedra | Ap | AI, DU, CA | [37] |

| Phytolaccaceae | Petiveria alliacea L. | Anamú | Ap | AI, SA, BP, CA | [38] |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago virginica L. | Platano | Lv | AI | [39] |

| Rubiaceae | Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) DC. | Uña de gato | Bk | AV, CA | [40] |

| Santalaceae | Phoradendron serotinum (Raf.) M. C. Johnst. | Muerdago | Lv | DB, CA | [41] |

| Talinaceae | Talinum triangulare (Jacq.) Willd. | Espinaca | Lv | CA, AV, DB | [42] |

| Urticaceae | Phenax rugosus (Poir.) Wedd. | Parietaria | Wp | WH, AV | [43] |

Other popular uses: AP: antiparasitic; AI: anti-inflammatory; AV: antiviral; BP: body pain; CA: cancer; CO: cough; DG: digestive; DI: diarrhea; DU: diuretic; DP: depression; FL: flu; SA: stomachache; TB: tuberculosis; WH: wound healing. Plant part: Ap: aerial parts; Bk: bark; Br: branches; Fr: fruit; Lv: leaves; Fw: flower; Rb: root bark; Rt: root; Sd: seeds; Sm: stem; Tb: tubercle; Wp: whole plant.

Table 6.

Medicinal plants used as immunostimulants with no pharmacological studies.

| Family | Scientific name | Common name | Plant part | Other popular uses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoxaceae | Sambucus mexicana C. Presl ex DC. | Sauco | Lv | AI, CO, DU | [60] |

| Agavaceae | Agave americana L. | Maguey | Ap | DU, CA | [61] |

| Agave salmiana Otto ex Salm-Dyck | Agave | Ap | DU, CA | [19] | |

| Agave tequilana F. A. C. Weber | Agave | Ap | DG | [62] | |

| Furcraea tuberosa (Mill.) W. T. Aiton | Maguey | Rt | AI | [31] | |

| Amaranthaceae | Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Epazote | Lv | AP, DI, CA | [63] |

| Chenopodium berlandieri Moq. | Epazote | Lv | BR, AP | [63] | |

| Chenopodium incisum Poir. | Epazote zorrillo | Lv | AP, DU | [63] | |

| Iresine ajuscana Suess. & Beyerle | Iresine | Lv | AI | [13] | |

| Anacardiaceae | Spondias mombin L. | Jobo | Fr | WH, DI | [64] |

| Asteraceae | Austroeupatorium inulifolium (Kunth) R. M. King & H. Rob. | Salvia amarga | Wp | CO | [65] |

| Bidens aurea (Aiton) Sherff | Aceitilla | Wp | DB, DI, SA | [66] | |

| Mikania cordifolia (L. f.) Willd. | Trepadora | Lv | AI, CO, BP | [67] | |

| Neurolaena lobata (L.) Cass. | Burrito | Rt | BP, DB, CA, AP | [67] | |

| Pterocaulon alopecuroides (Lam.) DC. | Varita pienegro | Wp | AV, CA | [68] | |

| Sanvitalia ocymoides DC. | Ojo de gallo | Wp | DI, SA | [69] | |

| Tagetes lucida Cav. | Pericón | Ap | SA, DP, CA | [33] | |

| Bignoniaceae | Crescentia alata Kunth | Huaje | Fr | TB, CA, DI | [70] |

| Parmentiera aculeata (Kunth) Seem. | Cuajilote | Ap | DB, BP, DU, CO, DI | [60] | |

| Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | Tronadora | Ap | DB, DU, CA | [71] | |

| Bixaceae | Bixa orellana L. | Achiote | Sd | CA, WH, DU | [68] |

| Bromeliaceae | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | Pineapple | Fr | DB, AH, CA | [72] |

| Burseraceae | Bursera copallifera (DC.) Bullock | Copal | Ap | AI, CA | [73] |

| Bursera fagaroides (Kunth) Engl. | Palo xixote | Bk | SA, CA | [74] | |

| Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. | Palo mulato | Lv | CO, SA, CA | [67] | |

| Commelinaceae | Zebrina pendula Schnizl. | Hierba de pollo | Lv | BP, WH, DB, CA | [43] |

| Cordiaceae | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | Aguardientillo | Lv | TB, WH | [67] |

| Varronia globosa Jacq. | Yerba de la sangre | Ap | DU | [23] | |

| Costaceae | Costus arabicus L. | Caña Guinea | Ap | AI | [75] |

| Cupressaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | Ahuehuete | Br | DI | [76] |

| Gesneriaceae | Moussonia deppeana (Schltdl. & Cham.) Hanst. | Tlalchichinole | Ap | WH, DI | [19] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha phleoides Cav. | Hierba del cáncer | Ap | CA, DI | [76] |

| Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (Mill.) I. M. Johnst. | Chaya | Lv | DB, CA | [28] | |

| Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Rumph. ex A. Juss. | Croton | Lv | DI | [28] | |

| Equisetaceae | Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun | Cola de caballo | Ap | DU | [77] |

| Fabaceae | Desmodium molliculum (Kunth) DC. | Manayupa | Ap | DU, WH | [40] |

| Eysenhardtia polystachya (Ortega) Sarg. | Palo dulce | Lv | DU, DB, WH, CA | [78] | |

| Haematoxylum brasiletto H. Karst. | Palo de Brasil | Bk | CO, DI | [19] | |

| Senna reticulata (Willd.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | Barajo | Ap | DB, WH | [43] | |

| Zornia thymifolia Kunth | Hierba de la vibora | Wp | DI, BP | [66] | |

| Juglandaceae | Juglans jamaicensis C. DC. | Palo de nuez | Bk | WH, AP | [31] |

| Juglans major (Torr.) A. Heller | Nogal | Lv | DU, AP, WH, CA | [76] | |

| Juglans mollis Engelm. | Nuez de caballo | Ap | WH, BP | [79] | |

| Krameriaceae | Krameria grayi Rose & J. H. Painter | Zarzaparrilla | Wp | DU | [20] |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia regla Cav. | Salvia | Lv | WH | [63] |

| Satureja macrostema (Moc. & Sessé ex Benth.) Briq. | Té de monte | Lv | CO | [80] | |

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum pachypodum (Nees) Kosterm. | Laurel | Ap | AP | [63] |

| Loranthaceae | Psittacanthus calyculatus (DC.) G. Don | Muerdago | Ap | CA, WH | [76] |

| Meliaceae | Cedrela odorata L. | Cedro | Bk | TB, DI | [37] |

| Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | Guayaba | Ap | AI, DI, CA | [81] |

| Moraceae | Brosimum alicastrum Sw. | Ojite | Lv | TB, FL | [82] |

| Musaceae | Musa sapientum L. | Banana | Fr | DI, DG | [83] |

| Onagraceae | Ludwigia peploides (Kunth) P. H. Raven | Clavo de la laguna | Ap | CO | [43] |

| Orobanchaceae | Castilleja tenuiflora Benth. | Cola de borrego | Ap | WH, CO, DI, CA | [84] |

| Papaveraceae | Bocconia frutescens L. | Gordolobo | Lv | CO, SA, CA | [35] |

| Passifloraceae | Turnera diffusa Willd. | Damiana | Lv | CO, DI, CA | [79] |

| Piperaceae | Piper auritum Kunth | Acoyo | Lv | SA, CO, DI | [85] |

| Polemoniaceae | Loeselia mexicana (Lam.) Brand | Espinosilla | Ap | DI, DU | [86] |

| Polygonaceae | Polygonum aviculare L. | Sanguinaria | Ap | DI, BR, DU, CA | [76] |

| Polypodiaceae | Polypodium polypodioides (L.) Watt | Helecho de resurrección | Lv | AP | [31] |

| Serpocaulon triseriale (Sw.) A. R. Sm. | Calaguala | Rt | WH, AH | [87] | |

| Rhizophoraceae | Rhizophora mangle L. | Mangle rojo | Bk | DI, DB, CA | [23] |

| Rubiaceae | Hamelia patens Jacq. | Escobetilla | Lv | AI, BP, CA | [67] |

| Salicaceae | Salix humboldtiana Willd. | Sauce criollo | Rt | AI, TB | [88] |

| Zuelania guidonia (Sw.) Britton & Millsp. | Guaguasí | Bk | WH, CA | [23] | |

| Selaginellaceae | Selaginella lepidophylla (Hook. & Grev.) Spring | Doradilla | Wp | DU, CO, CA | [86] |

| Smilacaceae | Smilax domingensis Willd. | Zarzaparrilla | Rt | DI, SA | [89] |

| Smilax moranensis M. Martens & Galeotti | Zarzaparrilla | Wp | DU, CO | [66] | |

| Smilax spinosa Mill. | Zarzaparrilla | Wp | BP, CA | [90] | |

| Solanaceae | Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | Jitomate | Fr | CO, CA | [13] |

| Solanum americanum Mill. | Hierba mora | Lv | BP, WH, CA | [91] | |

| Urticaceae | Urera baccifera (L.) Gaudich. ex Wedd. | Chichicate | Rt | DU, AI, BP | [23] |

| Verbenaceae | Verbena litoralis Kunth | Verbena negra | Lv | SA, CO, AH | [92] |

| Viscaceae | Phoradendron brachystachyum (DC.) Nutt. | Muerdago | Ap | DB, CA | [93] |

| Vitaceae | Cissus sicyoides L. | Tripa de Judas | Lv | BP, WH, AI, CA | [85] |

AP: antiparasitic; AI: anti-inflammatory; AV: antiviral; BP: body pain; CA: cancer; CO: cough; DG: digestive; DI: diarrhea; DU: diuretic; DP: depression; FL: flu; SA: stomachache; TB: tuberculosis; WH: wound healing. Plant part: Ap: aerial parts; Bk: bark; Br: branches; Fr: fruit; Lv: leaves; Fw: flower; Rb: root bark; Rt: root; Sd: seeds; Sm: stem; Tb: tubercle; Wp: whole plant.

A total of 20 plants, belonging to 15 botanical families, have in vitro studies regarding their immunostimulatory effects (Table 2). Furthermore, 8 plant species from 8 botanical families were assessed using in vivo assays (Table 3). A total of 11 compounds, isolated from 7 plants, have been tested using in vitro assays (Table 4). Only two compounds, isolated from two plants, were studied using in vivo models (Table 5).

Table 2.

Plant extracts with immunostimulatory effects tested using in vitro assays.

| Family | Scientific name | Plant part | Extract | Range of concentration tested μg/mL | Immunostimulatory effects, compared to untreated control [duration of the experiment] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Carlowrightia cordifolia A. Gray | Lv | Hex | 13.3 (mg/mL) | NO production (2.5-fold) at 13.3 mg/mL [48 h] in human primary peritoneal macrophage | [17] |

| Justicia spicigera Schltdl. | Lv | EtOH | 10–200 | Induction of phagocytosis (0.4-fold) at 200 μg/mL [48 h] by human primary lymphocytes against Saccharomyces cerevisiae

NO production (6.4-fold) in murine primary macrophages and H2O2 release (8.5-fold) at 200 μg/mL with murine monocyte–macrophages cocultured with Saccharomyces cerevisiae [48 h] Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (0.4-fold) at 200 µg/mL [48 h] |

[14] | |

| Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | Wp | H2O | 500 | Increased on IFN-γ promoter (1.9-fold) in Jurkat T cells at 500 µg/mL [72 h] | [44] |

| Xanthium strumarium L. | Wp | H2O | 10–100 | Proliferation of murine primary lymphocytes (13-fold) at 100 µg/mL [44 h] | [45] | |

| Cactaceae | Lophophora williamsii (Lem. ex Salm-Dyck) J. M. Coult. | Tb | MeOH | 0.18–18 | Proliferation of murine primary lymphocytes (2.5-fold) at 0.18–1.8 μg/mL [72 h] NO production (3-fold) at 18 μg/mL using murine peritoneal macrophages [72 h] |

[26] |

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Lv | H2O | 1.25–5 (mg/mL) | Production of IFN-γ (2.0-fold), IL-12 p40 (2.0-fold) in human primary lymphocytes at 1.25 mg/mL [24 h] | [46] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia cotinifolia L. | Latex | — | 25 | Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (1.6-fold) at 25 μg/mL [66 h] | [47] |

| Euphorbia hirta L. | Ap | EtOH | 0.06–500 (mg/mL) | Induction of phagocytosis of Candida albicans (2.0-fold) by primary murine macrophages at 500 mg/mL [1 h] | [29] | |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima Willd. ex Klotzsch | Lv | Hex : DCM : MeOH (2 : 1 : 1) | 25 | Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (6.5-fold) at 25 μg/mL [66 h] | [47] | |

| Hura crepitans L. | Lv | Hex : DCM : MeOH (2 : 1 : 1) | 25 | Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (0.85-fold) at 25 μg/mL [66 h] | [47] | |

| Hypericaceae | Hypericum perforatum L. | Wp | H2O | 750 | Proliferation of murine primary lymphocytes (1.6-fold) at 750 μg/mL [18 h] | [48] |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | Lv | MeOH | 3.91–250 | Proliferation of murine primary lymphocytes (1.6-fold) at 250 μg/mL [48 h] | [39] |

| Molluginaceae | Mollugo verticillata L. | Ap | EtOH | 25 | NO production (1.6-fold) at 25 μg/mL using murine peritoneal primary macrophages cocultures with Mycobacterium tuberculosis [48 h] | [44] |

| Nyctaginaceae | Bougainvillea × buttiana Holttum & Standl. | Fw | EtOH | 2.9–290 | H2O2 production (0.4-fold) at 2.9 μg/mL with murine primary peritoneal macrophages [24 h] Proliferation of murine primary peritoneal macrophages (0.6-fold) at 29 μg/mL [48 h] NO production (2.4-fold) at 290 μg/mL with murine primary peritoneal macrophages [48 h] |

[36] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus niruri L. | Lv | Hex : DCM : MeOH (2 : 1 : 1) | 25 | Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (1.3-fold) at 25 μg/mL [66 h] | [47] |

| Phytolaccaceae | Petiveria alliacea L. | Ap | H2O | 25 | Production of IL-6 (100-fold), IL-10 (14-fold), and IL-8 (12-fold) in dendritic cells at 25 μg/mL [48 h] | [49] |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago virginica L. | Lv | MeOH | 3.91–250 | Proliferation of murine primary lymphocytes at 250 μg/mL (1.6-fold) [48 h] | [39] |

| Rubiaceae | Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) DC. | Rb | H2O | 0.32–320 | NO production (1.5-fold) at 320 μg/mL using murine primary peritoneal macrophages [48 h] Production of IL-6 (7.2-fold) at 320 μg/mL in murine primary peritoneal macrophages [24 h] |

[50] |

| Santalaceae | Phoradendron serotinum (Raf.) M. C. Johnst. | Lv | EtOH | 1–50 | Proliferation of RAW 264.7 macrophages (0.2-fold) and murine primary splenocytes (0.3-fold) at 50 μg/mL [48 h] Lysosomal enzyme activity (0.2-fold) at 50 μg/mL using RAW 264.7 macrophages [48 h] Stimulation of NK cell activity (7.1-fold) at 50 μg/mL using murine primary splenocytes cocultured with K562 cells [48 h] Production of IFN-γ (1.6-fold), IL-2 (1.4-fold), and IL-6 (1.3-fold) at 50 μg/mL using murine primary splenocytes cocultured with K562 cells [48 h] |

[41] |

| Talinaceae | Talinum triangulare (Jacq.) Willd. | Sm | EtOH | 100–1000 | Proliferation of human primary lymphocytes (2-fold) at 1000 μg/mL [72 h] NO production (4-fold) at 1000 μg/mL [72 h] Production of IFN-γ (16-fold) at 500 μg/mL in human primary lymphocytes [72 h] |

[42] |

Solvent used for the extract: Hex: hexane; DCM: dichloromethane; MeOH: methanol; EtOH: ethanol; H2O: aqueous. Plant part: Rb: root bark; Tb: tubercle; Lv: leaves; Wp: whole plant.

Table 3.

Plant extracts with immunostimulatory effects tested using in vivo assays.

| Family | Scientific name | Plant part | Extract | Model of immunosuppression and duration of the experiment [range of dose tested] | Immunostimulatory effects (compared to immunosuppressed mice) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl. | Bk | H2O | BALB/c mice bearing lymphoma L5178Y for 10 days [10 mg/kg p.o.] | Proliferation of splenocytes (2.0-fold) at 10 mg/kg | [51] |

| Asteraceae | Tridax procumbens L. | Ap | H2O | Immunocompetent Swiss mice for 6 days [250 and 500 mg/kg i.p.] | Increase of leukocyte number (1.4-fold) at 500 mg/kg Increase in phagocytic index (0.3-fold) at 500 mg/kg |

[22] |

| Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia chrysantha (Jacq.) G. Nicholson | Lv | H2O : EtOH (1 : 1) | Wistar rats immunized with sheep red blood cells for 17 days [1000 mg/kg p.o.] | Increase of leucocyte number (1.2-fold) at 1000 mg/kg | [24] |

| Cactaceae | Lophocereus schottii (Engelm.) Britton & Rose | Sm | EtOH | BALB/c mice bearing lymphoma L5178Y for 22 days [10 mg/kg p.o.] | Proliferation of lymphocytes (0.2-fold) at 10 mg/kg | [25] |

| Molluginaceae | Mollugo verticillata L. | Ap | EtOH | Mice inoculated with 0.1 mg Bacillus Calmette–Guérin for 7 days [500 mg/kg p.o.] | NO production (3.1-fold) at 500 mg/kg | [52] |

| Phytolaccaceae | Petiveria alliacea L. | Ap | H2O | BALB/c mice treated with 5-fluorouracil for 4 days [400 and 1200 mg/kg p.o.] | Increase of leukocyte number (1.4-fold) at 1200 mg/kg | [53] |

| Santalaceae | Phoradendron serotinum (Raf.) M. C. Johnst. | Lv | EtOH | C57BL/6 mice bearing TC-1 tumor for 25 days [1–10 mg/kg i.p.] | Production of IFN-γ (1.3-fold), IL-2 (2.1-fold), and IL-6 (2.1-fold) at 10 mg/kg | [41] |

| Urticaceae | Phenax rugosus (Poir.) Wedd. | Lv | H2O : EtOH (1 : 1) | Wistar rats immunized with sheep red blood cells for 17 days [1000 mg/kg p.o.] | Increase of leucocyte number (1.5-fold) at 1000 mg/kg | [24] |

Solvent used for the extract: EtOH: ethanol; H2O: aqueous. Plant part: Rb: root bark; Tb: tubercle; Lv: leaves; Wp: whole plant; Ap: aerial parts; Sm: stem; Bk: bark.

Table 4.

In vitro immunostimulatory effects of plant compounds.

| Family | Scientific name | Compound | Group | Range of concentration tested µM | Immunostimulatory effects, compared to untreated control [duration of the experiment] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Justicia spicigera Schtdl. | Kaempferitrin | Flavonoid | 1–25 | Induction of phagocytosis (0.4-fold) at 200 µg/mL using RAW 264.7 macrophages [48 h] Induction of lysosomal enzyme activity (0.5-fold) at 25 µM with RAW 264.7 macrophages [48 h] Increase of NK cell activity (10-fold) at 25 µM with RAW 264.7 macrophages cocultured with K562 cells [48 h] |

[54] |

| Anacardiaceae | Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl. | Masticadienonic acid | Triterpenoid | 0.001–10 | NO production (1.8-fold) [72 h] at 0.001 µM in murine primary peritoneal macrophages | [55] |

| 3α-Hydroxymasticadienolic acid | Triterpenoid | 0.001–10 | NO production (1.7-fold) [72 h] at 1 µM in murine primary peritoneal macrophages | |||

| 24,25S-dihydromasticadienonic acid | Triterpenoid | 0.001–10 | NO production (1.3-fold) [72 h] at 0.01 µM in murine primary peritoneal macrophages | |||

| Masticadienolic acid | Triterpenoid | 0.001–10 | NO production (1.6-fold) [72 h] at 0.1 µM in murine primary peritoneal macrophages | |||

| Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | Centaurein Centaureidin |

Flavonoid Flavonoid |

EC50 = 0.14 µM EC50 = 2.5 µM |

Increase on IFN-γ promoter in Jurkat T cells [72 h] | [44] |

| Psacalium peltatum (Kunth) Cass. | Maturin acetate | Sesquiterpene | 1–25 | Increase of NK cell activity (7-fold) at 25 µM using murine primary splenocytes cocultured with K562 cells [48 h] Induction of lysosomal enzyme activity (0.2-fold) at 25 µM using RAW 264.7 macrophages [48 h] Proliferation of RAW 264.7 macrophages and murine primary splenocytes (0.2-fold, each) at 25 µM [48 h] |

[56] | |

| Fabaceae | Hymenaea courbaril L. | Xyloglucan | Polysaccharide | 0.1–50 | NO production (2.1-fold) at 0.25 µM with murine primary peritoneal macrophages [48 h] | [57] |

| Mucuna urens (L.) Medik. | Xyloglucan | Polysaccharide | 0.06–3.2 | NO production (1.4-fold) at 0.16 µM with murine primary peritoneal macrophages [48 h] | ||

| Phaseolus vulgaris | Pectic polysaccharide | Polysaccharide | 0.07–1.12 | Murine primary splenocytes proliferation (2.5-fold) at 1.12 µM [72 h] Murine primary thymocyte proliferation (2.1-fold) at 0.14 µM [72 h] |

[58] |

Table 5.

In vivo immunostimulatory effects of plant compounds.

| Family | Scientific name | Compound | Group | Model of immunosuppression and duration of the experiment [range of dose tested] | Immunostimulatory effects (compared to immunosuppressed mice) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asteraceae | Psacalium peltatum (Kunth) Cass. | Maturin acetate | Sesquiterpene | BALB/c mice treated with 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide for 14 days [10–50 mg/kg i.p.] | Production of IFN-γ (1.4-fold) and IL-2 (1.8-fold) | [56] |

| Rubiaceae | Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) DC. | Pteropodine | Alkaloid | Immunocompetent mice for 4 days [100–600 mg/kg i.p.] | Lymphocyte proliferation (1.6-fold) at 600 mg/kg | [59] |

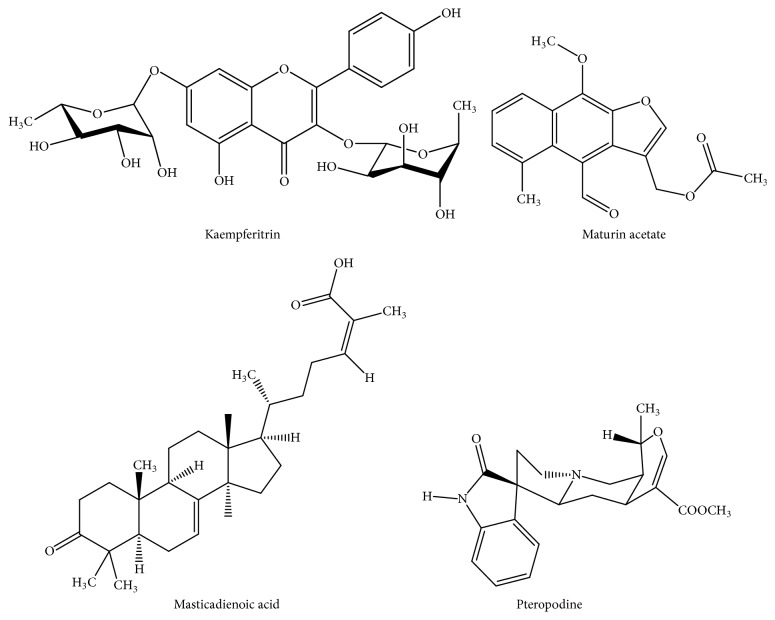

Among the in vitro studies, Lophophora williamsii was one of the plant species that showed good immunostimulatory effects. This plant tested at 0.18 μg/mL showed a similar activity (2.4-fold, compared to untreated cells) on the proliferation of human primary lymphocytes, compared to the positive control 0.6 μg/mL concanavalin A [26]. Further studies with Lophophora williamsii, as well as the isolation and purification of its active compounds, are highly recommended. Among the in vivo studies, an ethanol extract from Phoradendron serotinum leaves, tested from 1 to 10 mg/kg i.p., showed immunostimulatory effects, in a dose-dependent manner, by increasing the levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-6 in serum from C57BL/6 mice bearing TC-1 tumor [41]. The immunostimulatory effects obtained using in vitro studies were confirmed in in vivo studies for some plant species such as Mollugo verticillata, Phoradendron serotinum, and Petiveria alliacea and compounds such as maturin acetate (Figure 1). This indicates that these plants and the compound can be metabolized, and their immunostimulatory effects are also shown in animals.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of some compounds with immunostimulatory effects isolated from medicinal plants.

On the other hand, in many works cited in this review, only one concentration or dose was tested. Further studies will be required to obtain the EC50 or ED50 values, if possible, and analyze whether the plant extracts or compounds induce a concentration/dose-dependent effect. In many studies, a single immunostimulant test is used (e.g., the NO production). Authors are encouraged to perform more than one immunostimulatory test in further studies to provide more information on the immunostimulant effects of plant extracts or compounds. In some cases, the initial screening of the in vivo immunostimulatory effects is carried out using immunocompetent mice. Further studies are necessary to be performed on plant extracts and compounds using models of immunosuppressed mice, induced with chemical or biological agents.

4. Medicinal Plants Used as Immunostimulants without Pharmacological Studies

We documented 75 medicinal plants used as immunostimulants that lack pharmacological studies (Table 6). Plants from the Smilax genus (S. domingensis, S. moranensis, and S. spinosa) and the Juglans genus (J. major, J. mollis, and J. jamaicensis) could be an excellent option for the isolation and identification of immunostimulatory agents because compounds isolated from their related species have shown immunostimulatory activity. Smilaxin (1.56 μM), a 30 kDa protein obtained from Smilax glabra, increased the proliferation of splenocytes and bone marrow cells with similar activity to the positive control 0.52 μM concanavalin A [95]. A water-soluble polysaccharide, called JRP1, isolated from Juglans mandshurica showed in vivo immunostimulatory effects by increasing the release of IFN-γ and IL-2 in an immunosuppressed model of mice bearing S-180 tumor [96]. Taking this into consideration, further studies with plants from the Smilax and Juglans genera should be carried out. Furthermore, mistletoe species such as Phoradendron brachystachyum and Psittacanthus calyculathus could be a good option for discovering immunostimulatory agents since the related species Phoradendron serotinum showed good immunostimulatory activity [41]. However, the toxicity of the mistletoe species should be assessed.

5. Further Considerations

More ethnobotanical studies are necessary to provide information on medicinal plants used as immunostimulants in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. The ethnomedicinal information of plant species will be updated with these studies.

The toxicity of plant species cited in this review should also be assessed. For instance, Xanthium strumarium is considered a toxic plant. Recently, it was described that this plant induces hepatotoxicity [97]. On the contrary, Hymenaea courbaril was shown to lack genotoxic and mutagenic effects [98]. Toxicological studies are necessary to provide safety in the use of plant extracts and their compounds in clinical trials.

To our knowledge, there are no pharmacokinetic studies carried out with plant compounds cited in this review. This might be due to (a) the lack of established methodologies for their quantitation, (b) the quantity of the obtained compound being not enough to carry out a pharmacokinetic study, and (c) many plants extracts not being chemically characterized, and there is no main metabolite for its quantification using HPLC. Further pharmacokinetic studies will provide additional pharmacological information prior to carrying out clinical trials. The isolation and elucidation of the structure of bioactive principles should also be encouraged.

Eight percent of medicinal plants listed in this review are classified as endangered. In the order of most endangered, Juglans jamaicensis, Cedrela odorata, and Lophophora williamsii are cataloged as vulnerable, whereas Taxodium mucronatum, Rhizophora mangle, Eysenhardtia polystachya, Cordia alliodora, and Hymenaea courbaril are cataloged as of least concern [99]. For instance, Lophophora williamsii (peyote) is a species that has been overexploited because of its high content of hallucinogenic alkaloids. The conservation of these species, as well as their habitats, should be encouraged by national and international programs to preserve biodiversity.

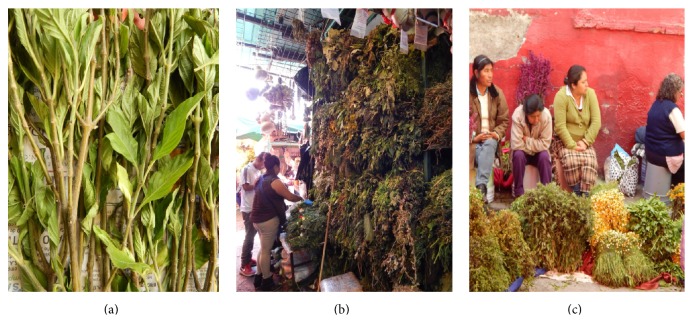

There is null or limited information regarding the trade of medicinal plants used as immunostimulants. Therefore, we performed direct interviews (n = 45) with local sellers of medicinal plants in Mexico, called “hierberos” or “yerbateros” in 7 different markets (Portales, Sonora, Xochimilco, Milpa Alta, Tlahuac, and Ozumba) located in Mexico City and the metropolitan area (Figure 2). Two of the markets are located in Xochimilco. In order of importance, the most recommended plant species used as immunostimulants are Justicia spicigera, Polygonum aviculare, Carlowrightia cordifolia, Amphipterygium adstringens, Uncaria tomentosa, and others. It was interesting to find that 85% of yerbateros recommended the use of Justicia spicigera as immunostimulant (Figure 2(a)). Its way of preparation consists of the following: four or five branches and leaves are boiled with 1 L of water during 30 min. The recommended administration is 3 times daily. The rest of plant species were cited by less than 10% of yerbateros.

Figure 2.

Trade of medicinal plants used as immunostimulants in Mexico City. (a) Justicia spicigera was the most cited plant species used as immunostimulatory agent. (b and c) Traditional markets in Mexico City, showing the sellers of medicinal plants called hierberos or yerbateros.

The demand for medicinal plants used as immunostimulants clearly indicates that these plant species are a current topic of interest. This indicates that ethnobotanical knowledge is a valuable tool, which supports the selection of plants to carry out pharmacological studies. Some of the medicinal plants cited in our survey have been pharmacologically investigated. Carlowrightia cordifolia showed poor immunostimulatory effects [17]. Amphipterygium adstringens showed in vivo immunostimulatory effects [51], whereas masticadienonic acid (Figure 1), its active compound at 0.001 μM, increased the NO production (1.8 fold) with higher activity compared to 0.001 μM ursolic acid (1.4 fold) [55]. Uncaria tomentosa showed in vitro immunostimulatory effects [50], whereas pteridine (Figure 1), its active compound, tested at 600 mg/kg i.p., increased the lymphocyte proliferation in immunocompetent mice [59]. Justicia spicigera and kaempferitrin (Figure 1), its active compound, showed in vitro immunostimulatory effects [14, 54]. Nevertheless, the in vivo immunostimulatory effects remain to be performed with Justicia spicigera, kaempferitrin, and masticadienonic acid. The molecular mechanism by which this plant and the compounds exert their immunostimulatory effects should also be assessed.

Finally, this review highlights the need to perform pharmacological, phytochemical, toxicological, and ethnobotanical studies with medicinal flora, from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, to obtain new immunostimulatory agents.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the Directorate for Research Support and Postgraduate Programs at the University of Guanajuato for their support in the editing of the English-language version of this paper.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Baniyash M. Chronic inflammation, immunosuppression and cancer: new insights and outlook. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2006;16(1):80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manu K. A., Kuttan G. Immunomodulatory activities of Punarnavine, an alkaloid from Boerhaavia diffusa . Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2009;31(3):377–387. doi: 10.1080/08923970802702036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alamgir M., Uddin S. J. Recent advances on the ethnomedicinal plants as immunomodulatory agents. In: Chattopadhyay D., editor. Ethnomedicine: A Source of Complementary Therapeutics. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2010. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brutkiewicz R. R., Sriram V. Natural killer T (NKT) cells and their role in antitumor immunity. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2002;41(3):287–298. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page R. C., Davies P., Allison A. C. The macrophage as a secretory cell. International Review of Cytology. 1978;52:119–157. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60755-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavier P., Edgington T. S. Human monocyte-mediated tumor cytotoxicity. I. Demonstration of an oxygen-dependent myeloperoxidase-independent mechanism. Journal of Immunology. 1984;132(4):1980–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbs J. B., Jr., Vavrin Z., Taintor R. R. L-arginine is required for expression of the activated macrophage effector mechanism causing selective metabolic inhibition in target cells. Journal of Immunology. 1987;138(2):550–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosmann T. R., Coffman R. L. Heterogeneity of cytokine secretion patterns and functions of helper T cells. Advances in Immunology. 1989;46:111–147. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asano Y., Kaneda K., Hiragushi J., Tsuchida T., Higashino K. The tumor-bearing state induces augmented responses of organ-associated lymphocytes to high-dose interleukin-2 therapy in mice. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy. 1997;45(2):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s002620050403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroder K., Hertzog P. J., Ravasi T., Hume D. A. Interferon-γ: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2004;75(2):163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patwardhan B., Kalbag D., Patki P. S., Nagsampagi B. A. Search of immunomodulatory agents. Indian Drugs. 1990;28(2):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulitzeanu D. Immunosuppressive factors in human cancer. Advances in Cancer Research. 1993;60:247–267. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bueno J. G., Isaza G., Gutiérrez F., Carmona W. D., Pérez J. E. Estudio etnofarmacológico de plantas usadas empíricamente por posibles efectos inmunoestimulantes. Revista Médica de Risaralda. 2001;7(1):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso-Castro A. J., Ortiz-Sánchez E., Domínguez F., et al. Antitumor and immunomodulatory effects of Justicia spicigera Schltdl (Acanthaceae) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;141(3):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haskell C. M. Immunologic aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1977;17:179–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.17.040177.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh K. P., Gupta R. K., Shau H., Ray P. K. Effect of ASTA-z 7575 (INN maphosphamide) on human lymphokine-activated killer cell induction. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 1993;15(5):525–538. doi: 10.3109/08923979309019729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz-Vega D. E., Aguilar A., Vargas-Villarreal J., Verde-Star M. J., González-Garza M. T. Leaf extracts of Carlowrightia cordifolia induce macrophage nitric oxide production. Life Sciences. 2002;70(11):1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrera-Arellano A., Jaime-Delgado M., Herrera-Alvarez S., Oaxaca-Navarro J., Salazar-Martínez E. Uso de terapia alternativa/complementaria en pacientes seropositivos a VIH. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. 2009;47(6):651–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bautista-Bautista M. D. R. Monografias de plantas utilizadas como anticancerigenas en la medicina tradicional Hidalguense [Ph.D. thesis] Pachuca, Mexico: Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Hidalgo; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barba-Ávila M. D., Hernandez-Duque M. C., de la Cerda-Lemus M. Plantas Útiles de la Región Semiárida de Aguascalientes. Aguascalientes, México: Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alarcon-Aguilar F. J., Fortis-Barrera A., Angeles-Mejia S., et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of a hypoglycemic fructan fraction from Psacalium peltatum (H.B.K.) Cass. in streptozotocin-induced diabetes mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;132(2):400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiwari U., Rastogi B., Singh P., Saraf D. K., Vyas S. P. Immunomodulatory effects of aqueous extract of Tridax procumbens in experimental animals. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;92(1):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godínez-Carballo D., Volpato G. Plantas medicinales que se venden en el mercado El Río, Camagüey, Cuba. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad. 2008;79(1):243–259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez J. E., Isaza G., Bueno J. G. Efecto de los extractos de Phenax rugosus, Tabebuia chrysantha, Althernantera williamsii y Solanum dolichosepalum sobre el leucograma y la producción de anticuerpos en ratas. Revista Médica de Risaralda. 2004;10(2):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orozco-Barocio A., Paniagua-Domínguez B. L., Benítez-Saldaña P. A., Flores-Torales E., Velázquez-Magaña S., Nava H. J. A. Cytotoxic effect of the ethanolic extract of Lophocereus schottii: a Mexican medicinal plant. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary, and Alternative Medicines. 2013;10(3):397–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franco-Molina M., Gomez-Flores R., Tamez-Guerra P., Tamez-Guerra R., Castillo-Leon L., Rodríguez-Padilla C. In vitro immunopotentiating properties and tumour cell toxicity induced by Lophophora williamsii (Peyote) cactus methanolic extract. Phytotherapy Research. 2003;17(9):1076–1081. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morales A. R. Frutoterapia: La Fruta, el Oro de Mil Colores. Madrid, Spain: Edaf Editorial; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llanes-Coronel D. S. Actividad inmunomoduladora de 10 plantas de la familia Euphorbiaceae [M.S. thesis] Medellín, Colombia: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2009. http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/1787/1/37277968.2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramesh K. V., Padmavathi K. Assessment of immunomodulatory activity of Euphorbia hirta L. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2010;72(5):621–625. doi: 10.4103/0250-474x.78532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alzate-Tamayo L. M., Arteaga-Gonzalez D. M., Jaramillo-Garces Y. Pharmacological properties of the carob tree (Hymenaea courbaril Linneaus) interesting for the food industry. Revista Lasallista de Investigación. 2008;5(2):100–111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuñez-Melendez E. Plantas Medicinales de Puerto Rico: Folklore y Fundamentos Científicos. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espinosa-Alonso L. G. Diversidad genética y caracterización nutricional y nutracéutica del frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) [Ph.D. thesis] Irapuato, Mexico: Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mejía-Hernández L. M. Estudio comparativo de la actividad hematopoyética in vitro de Hypericum perforatum y Tagetes lucida [Ph.D. thesis] Distrito Federal, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Iztapalapa; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall-Ramírez V., Rocha-Palma M., Rodriguez-Vega E. Plantas Medicinales. Volumen II. San Pedro de Montes de Oca, Costa Rica; 2002. (Centro Nacional de Información de Medicamentos, Universidad de Costa Rica). http://sibdi.ucr.ac.cr/boletinespdf/cimed27.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosales-Hernandez B. Actividad antimicobacteriana sobre Mycobacterium tuberculosis y/o activadora de macrófagos de extractos de plantas Mexicanas conocidas como gordolobos [M.S. thesis] Nuevo León, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arteaga Figueroa L., Barbosa Navarro L., Patiño Vera M., Petricevich V. L. Preliminary studies of the immunomodulator effect of the Bougainvillea xbuttiana extract in a mouse model. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/479412.479412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rengifo-Salgado E. Intern report. Iquitos, Peru: Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana; 2011. Contribución de la etnomedicina. Plantas medicinales a la salud de la población en el Amazonia. http://www.acadnacmedicina.org.pe/publicaciones/Anales%202010/contribucion_etnomedicina.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemus-Rodríguez Z., Garcia-Perez M. E., Batista-Duharte A., et al. La tableta de anamú: un medicamento herbolario inmunoestimulante. MEDISAN. 2004;8(3):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez-Flores R., Verastegui-Flores L., Quintanilla-Licea R., et al. In vitro rat lymphocyte proliferation induced by Ocinum basilicum, Persea americana, Plantago virginica, and Rosa spp. extracts. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2008;2(1):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madaleno I. M. Etno-farmacología en Iberoamérica, una alternativa a la globalización de las prácticas de cura. Cuadernos Geográficos. 2007;41:61–95. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alonso-Castro A. J., Juárez-Vázquez M. D. C., Domínguez F., et al. The antitumoral effect of the American mistletoe Phoradendron serotinum (Raf.) M.C. Johnst. (Viscaceae) is associated with the release of immunity-related cytokines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;142(3):857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao D. Y., Chai Y. C., Wang S. H., Chen C. W., Tsai M. S. Antioxidant activities and contents of flavonoids and phenolic acids of Talinum triangulare extracts and their immunomodulatory effects. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2015;23(2):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramírez-Cárdenas A., Isaza-Mejia G., Perez-Cardenas J. E. Especies vegetales investigadas por sus propiedades antimicrobianas, inmunomoduladoras, e hipoglucemiantes en el departamento de Caldas (Colombia, SudAmerica) Biosalud. 2013;12(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang S.-L., Chiang Y.-M., Chang C. L.-T., et al. Flavonoids, centaurein and centaureidin, from Bidens pilosa, stimulate IFN-γ expression. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112(2):232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moon E. Y., Park S. Y., Ahn M. J., Ahn J. W., Zee O. P., Park E. Immunomodulating activities of water extract from Xanthium strumarium (II): immunostimulating effects of the water layer after treated with chloroform. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 1991;14(3):217–224. doi: 10.1007/bf02876859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otsuki N., Dang N. H., Kumagai E., Kondo A., Iwata S., Morimoto C. Aqueous extract of Carica papaya leaves exhibits anti-tumor activity and immunomodulatory effects. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;127(3):760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Llanes-Coronel D. S., Gámez-Díaz L. Y., Suarez-Quintero L. P., et al. New promising Euphorbiaceae extracts with activity in human lymphocytes from primary cell cultures. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2011;33(2):279–290. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2010.502173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilasrusmee C., Kittur S., Siddiqui J., Bruch D., Wilasrusmee S., Kittur D. S. In vitro immunomodulatory effects of ten commonly used herbs on murine lymphocytes. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(4):467–475. doi: 10.1089/107555302760253667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santander S. P., Hernández J. F., Cifuentes C., et al. Immunomodulatory effects of aqueous and organic fractions from Petiveria alliacea on human dendritic cells. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2012;40(4):833–844. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenzi R. M., Campestrini L. H., Okumura L. M., et al. Effects of aqueous fractions of Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) D.C. on macrophage modulatory activities. Food Research International. 2013;53(2):767–779. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramírez-León A., Barajas-Martinez H., Flores-Torales E., Orozco-Barocio A. Immunostimulating effect of aqueous extract of Amphypterygium adstringens on immune cellular response in immunosuppressed mice. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;10(1):35–39. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferreira A. P., Soares G. L. G., Salgado C. A., et al. Immunomodulatory activity of Mollugo verticillata L. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(2-3):154–158. doi: 10.1078/094471103321659861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batista-Duhuarte A., Urdaneta-Laffita I., Colón-Suarez M., et al. Efecto protector de Petiveria alliacea L. (Anamú) sobre la inmunosupresión inducida por 5-fluoruracilo en ratones Balb/c. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. 2011;10(3):256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Del Carmen Juárez-Vázquez M., Josabad Alonso-Castro A., García-Carrancá A. Kaempferitrin induces immunostimulatory effects in vitro . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;148(1):337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oviedo Chávez I., Ramírez Apan T., Martínez-Vázquez M. Cytotoxic activity and effect on nitric oxide production of tirucallane-type triterpenes. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2005;57(9):1087–1091. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.9.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juárez-Vázquez M. D. C., Alonso-Castro A. J., Rojano-Vilchis N., Jiménez-Estrada M., García-Carrancá A. Maturin acetate from Psacalium peltatum (Kunth) Cass. (Asteraceae) induces immunostimulatory effects in vitro and in vivo . Toxicology in Vitro. 2013;27(3):1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosário M. M. T., Noleto G. R., Bento J. F., Reicher F., Oliveira M. B. M., Petkowicz C. L. O. Effect of storage xyloglucans on peritoneal macrophages. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(2):464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patra P., Das D., Behera B., Maiti T. K., Islam S. S. Structure elucidation of an immunoenhancing pectic polysaccharide isolated from aqueous extract of pods of green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Carbohydrate Polymers. 2012;87(3):2169–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.10.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paniagua-Pérez R., Madrigal-Bujaidar E., Molina-Jasso D., et al. Antigenotoxic, antioxidant and lymphocyte induction effects produced by pteropodine. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2009;104(3):222–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lagunes-Gutiérrez F. Vademecum de plantas medicinales del municipio de puente nacional, Veracruz [Bachelor thesis] Xalapa, Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guevara-Apráez C. S., Vallejo-Castillo E. J. Potencialidades medicinales de los géneros Furcraea y Agave . Revista Cubana de Plantas Medicinales. 2014;19(3):248–263. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gutiérrez G., Siqueiros-Delgado M. E., Rodríguez-Chávez H. E., et al. Usos potenciales de las plantas en tres áreas protegidas del Estado de Guanajuato. In: Cruz-Angón A., Melgarejo E. D., Contreras-Ruiz Esparza A. V., González-Gutiérrez M. A., editors. La Biodiversidad en Guanajuato: Estudio de Estado. Vol. 1. Guanajuato, Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), Instituto de Ecología del Estado de Guanajuato; 2012. pp. 262–265. http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/region/EEB/pdf/guanajuato_vol1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Estrada-Castillón E., Villarreal-Quintanilla J. A., Salinas-Rodríguez M. M. Usos tradicionales de los recursos naturales. In: Cantú-Ayala C., Rovalo-Merino M., Marmolejo-Moncivais J., et al., editors. Historia Natural del Parque Nacional Cumbres de Monterrey, Mexico. Monterrey, Mexico: Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon; 2013. pp. 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hijuelo-Borrero Y. Etnobótanica y medicina herbolaria. Batey: Revista Cubana de Antropología Sociocultural. 2013;3(3):84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramírez-Cárdenas A., Isaza-Mejía G., Pérez-Cárdenas J. E. Especies vegetales investigadas por sus propiedades antimicrobianas, inmunomoduladoras e hipoglucemiantes en el Departamento de Caldas (Colombia, SudAmerica) Biosalud. 2013;12(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bello-González M. A., Hernández-Muñoz S., Lara-Chávez M. B. C., et al. Plantas utiles de la comunidad indígena Nuevo San Juan Paranguricutiro, Michoacan, Mexico. Polibotánica. 2015;39:175–215. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Méndoza Marquez P. E. Las plantas medicinales de la selva alta perennifolia de los Tuxtlas, Veracruz: un enfoque etnofarmacologico-quimico [Bachelor thesis] Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico; 2000. http://www.ibiologia.unam.mx/directorio/r/ricker_pdf/TESIS%20Pilar%20Mendoza%202000.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Basualdo I., Soria N., Degen R., et al. Plantas medicinales comercializadas en los mercados de Asunción y Gran Asunción parte 1. Rojasiana. 2004;6:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 69.González-Elizondo M., López-Enríquez I. L., González-Elizondo M. S., et al. Plantas Medicinales del Estado de Durango y Zonas Aledañas. Mexico City, Mexico: Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional Unidad Durango, Instituto Politécnico Nacional; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Solares-Arenas F. Etnobotanica y usos potenciales del cirian (Crescentia alata HBK) en el estado de Morelos. Polibótanica. 2004;18:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Del Amo S. R. Plantas Medicinales del Estado de Veracruz. Xalapa, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Investigacion en Recursos Bioticos, INIREB; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Errasti M. E. Estudio de posibles aplicaciones farmacológicas de extractos de especies de bromeliáceas y su comparación con bromelina [Ph.D. thesis] La Plata, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de la Plata; 2013. http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/31727/Documento_completo__.Errasti.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Méndez-Hernández A., Hernández-Hernández A. A., López-Santiago M. D. C., et al. Herbolaria Oaxaqueña para la Salud. México City, México: Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puebla-Pérez A. M. Actividad citotóxica, antitumoral e inmunológica de extractos obtenidos de Bursera fagaroides [Ph.D. thesis] Guadalajara, Mexico: Universidad de Guadalajara; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 75.del C Avelino-Flores M. Evaluación de la actividad antiproliferativa de extractos de cinco plantas medicinales de la región de Cuetzalan, Puebla sobre una línea celular de cáncer cervicouterino [M.S. thesis] Tlaxcala, Mexico: Centro de Investigación en Biotecnología Avanzada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farmacopea Herbolaria de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (FHEUM) Secretaria de Salud. 2nd. Distrito Federal, Mexico: Farmacopea Herbolaria de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (FHEUM); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gallardo-Pérez J. C., Esparza-Aguilar M. L., Gómez-Campos A. Importancia etnobotánica de una planta vascular sin semilla en México: equisetum. Polibotánica. 2006;21:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cappiello J. Adquisición, transmisión y socialización de los saberes tradicionales asociados a las plantas medicinales en Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, Morelos—México [M.S. thesis] Paris, France: Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle; 2010. http://atekokolli.org/CAPPIELLO_2010_Esp_Full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pérez-Meseguer J. Aislamiento, purificación y caracterización de compuestos con actividad antioxidante e inmunomoduladora de Juglans mollis y Turnera diffusa [Ph.D. thesis] Monterrey, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Linares-Mazari E., Flores-Peñafiel B., Bye R. Selección de Plantas Medicinales de México. Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Limusa; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Segleau-Earle J. Árboles medicinales: el guayabo. Kurú: Revista Forestal (Costa Rica) 2008;5(15):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gómez-Pompa A. La etnobotánica en México. Biótica, Instituto Nacional de Investigación Sobre Recursos Bióticos. 1982;7(2):151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan-Quijano J. G., Pat-Canché M. K., Saragos-Mendez J. Conocimiento etnobotánico de las plantas utilizadas en Chancah Veracruz, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Teoría y Praxis. 2013;14:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hernández F. Historia Natural de Nueva España. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Argueta V. A., Cano A. L. M., Rodarte M. E. Flora Medicinal Indigena de Mexico. Instituto Nacional Indigenista; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 86.González M. Especies Vegetales de Importancia Económica en la Ciudad México. México City, Mexico: Editorial Porrua; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mitre M. E., Camacho N. Plantas Medicinales de la Cuenca Hidrográfica del Canal de Panamá. Vol. 6. Panamá, Panama: Editora Sibauste; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Navarro-Perez L. C., Avendaño-Reyes S. Flora útil del municipio de Astancinga, Veracruz, México. Polibotánica. 2002;14:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 89.González-Cárdenas R. M. Efecto inmunoestimulante de la zarzaparrilla (Smilax dominguensis) suministrada en pollo de engorde [Bachelor thesis] Guatemala City, Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala; 2009. http://biblioteca.usac.edu.gt/tesis/10/10_1185.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carbonó-Delahoz E., Dib-Diazgranados J. C. Plantas medicinales usadas por los Cogui en el río Palomino, Sierra nevada de Santa Marta (Colombia) Caldasia. 2013;35(2):333–350. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cáceres A., Gir L. M. Desarrollo de medicamentos fitoterápicos a partir de plantas medicinales de Guatemala. Revista de Fitoterapia. 2002;2(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vásquez R. Sistemática de las plantas medicinales de uso frecuente en el área de Iquitos. Folia Amazonica. 1992;4(1):65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 93.López-Martínez S., Navarrete-Vázquez G., Estrada-Soto S., León-Rivera I., Rios M. Y. Chemical constituents of the hemiparasitic plant Phoradendron brachystachyum DC Nutt (Viscaceae) Natural Product Research. 2013;27(2):130–136. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.662646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alonso-Castro A. J., Villarreal M. L., Salazar-Olivo L. A., Gomez-Sanchez M., Dominguez F., Garcia-Carranca A. Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;133(3):945–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chu K. T., Ng T. B. Smilaxin, a novel protein with immunostimulatory, antiproliferative, and HIV-1-reverse transcriptase inhibitory activities from fresh Smilax glabra rhizomes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;340(1):118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruijun W., Shi W., Yijun X., Mengwuliji T., Lijuan Z., Yumin W. Antitumor effects and immune regulation activities of a purified polysaccharide extracted from Juglan regia. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;72:771–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xue L.-M., Zhang Q.-Y., Han P., et al. Hepatotoxic constituents and toxicological mechanism of Xanthium strumarium L. fruits. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;152(2):272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vale C. R., Silva C. R., Oliveira C. M. A., Silva A. L., Carvalho S., Chen-Chen L. Assessment of toxic, genotoxic, antigenotoxic, and recombinogenic activities of Hymenaea courbaril (Fabaceae) in Drosophila melanogaster and mice. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2013;12(3):2712–2724. doi: 10.4238/2013.july.30.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 2014, http://www.iucnredlist.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]