Abstract

ABO incompatibility has been considered as an important immunological barrier for renal transplantation. With the advent of effective preconditioning protocols, it is now possible to do renal transplants across ABO barrier. We hereby present a single center retrospective analysis of all consecutive ABOi renal transplants performed from November 2011 to August 2014. Preconditioning protocol consisted of rituximab, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate sodium, and prednisolone. The outcome of these ABOi transplants was compared with all other consecutive ABO-compatible (ABOc) renal transplants performed during same time. Twenty ABOi renal transplants were performed during the study period. Anti-blood group antibody titer varied from 1:2 to 1:512. Patient and graft survival was comparable between ABOi and ABOc groups. Biopsy proven acute rejection rate was 15% in ABOi group, which was similar to ABOc group (16.29%). There were no antibody-mediated rejections in ABOi group. The infection rate was also comparable. We conclude that the short-term outcome of ABOi and ABOc transplants is comparable. ABOi transplants should be promoted in developing countries to expand the donor pool.

Keywords: ABO incompatible, ABOi, developing world, India, renal transplantation

Introduction

Kidney transplantation is the best form of renal replacement therapy (RRT) for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients.[1] Only 10% of ESRD patients receive any form of RRT in India and only 2% undergo renal transplantation.[2] As per the Indian Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Registry, 39% of CKD 5 patients were on RRT and 2% were being worked up for renal transplant.[3] Renal transplant options for ESRD patients are limited. Deceased donor transplantation is still in its nascent stage. ABO incompatibility is an important limiting factor amongst willing donors, leading to rejection of approximately 35% donors.[4] In such a scenario, options are limited. One can opt for paired kidney exchange transplantation. Although it is being done at individual centers, there are no regional bodies to facilitate such exchanges between different centers and there is no national registry. This limits the number of such exchanges significantly. Also, many recipients are reluctant to accept kidney from donor outside their family in exchange of their own. ABO-incompatible (ABOi) transplant comes across as a viable alternative in such a scenario.

Although worldwide popularity of ABOi renal transplant is increasing, experience from developing world is limited. Major concerns are high cost, risk of antibody-mediated rejection and increased incidence of posttransplant infections. We hereby present experience of ABOi renal transplant at our center, a tertiary care center in north India.

Subjects and Methods

This is a single center retrospective analysis of consecutive renal transplants from November 2011, when the first ABOi renal transplant was performed at our center, till August 31, 2014. A total of 20 ABOi and 669 blood group compatible (ABOc) renal transplants were done.

Antibody titer determination

Once a suitable donor was identified, recipient serum was tested for IgG and IgM antibody titer against donor ABO blood group antigens. This was done using column agglutination technology with Low-Ionic-Strength Saline-Indirect Antiglobulin Test Technique (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Johnson and Johnson, USA). The cassettes used were anti-human globulin type. This method of antibody titer determination is known to be more sensitive than the conventional tube test.

All prospective donors underwent standard investigations after detailed history and physical examination. Crossmatch was performed by complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and flow cytometry.

Preconditioning and immunosuppression protocol

Patients received intravenous rituximab (200 mg) 2 weeks pretransplant. After a week, tacrolimus (0.05 mg/kg/day in two divided doses) and mycophenolate sodium (720 mg twice daily) were started, and patient was admitted for plasmapheresis. Tacrolimus trough level was targeted at 8–12 ng/ml. Alternate day plasmapheresis was performed followed by administration of IVIG (100 mg/kg/dose) postplasmapheresis. Low dose of rituximab and IVIG were used based on previous published good outcomes with these doses.[5,6,7] Daily isoagglutinin IgG titer was monitored, and transplantation was done once it reached 1:8. Baseline antibody titer was ≤1:8 in 3 patients who did not require plasmapheresis. Of remaining 17 patients, first 5 received conventional plasma exchange while double filtration plasmapheresis (DFPP) was used for antibody removal in other 12. DFPP leads to selective removal of the immunoglobulin fraction from the serum, minimizing the volume of substitution fluid required.[8]

Intraoperatively, patients received intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg) and intravenous basiliximab (20 mg) induction. Dose of basiliximab was repeated on postoperative day four. One patient received anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) as inducing agent (1.5 mg/kg intravenous for two doses) due to weakly positive B cell flowcytometry crossmatch and presence of donor specific antibodies. One of the renal transplant recipients did not receive any induction in view of presence of recent pulmonary tuberculosis. Intravenous hydrocortisone was given on the day of transplant followed by oral prednisolone at 40 mg/day next day onward. This was tapered to 20 mg/day on discharge. Isoagglutinin titer was monitored daily until discharge, and plasmapheresis was done in case of rising titers. Two patients required posttransplant plasmapheresis. All patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis for pneumocystis jiroveci infection and clotrimazole prophylaxis for fungal infection. Valganciclovir prophylaxis was given to patients receiving ATG induction or those with D+ R-cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG serology.

In ABOc group, basiliximab induction was offered to all the patients. But as patients pay for the cost of transplant and drugs, only 55% received basiliximab induction. Thymoglobulin was offered to immunologically high-risk recipients such as those with previous history of multiple blood transfusions, second or more renal transplant, multiple pregnancies, and wife recipient. Five percent of patients received thymoglobulin induction.

Post-transplant follow-up

Patients were followed up twice weekly for 1st month, weekly for next 1-month, once a fortnight till the 3rd month and thereafter monthly for one year. After 1st year, follow-up was once in 2–3 months. During every visit, renal function tests including serum creatinine and hemogram were monitored. Isoagglutinin titer was done twice weekly for 2 weeks post-discharge and weekly for next 2 weeks thereafter. Tacrolimus/cyclosporine level was done as per the need, decided by the treating physician. Tacrolimus trough level target was 8–12 ng/ml during first 3 months, 5–8 ng/ml from 3 to 6 months and <5 ng/ml thereafter. Cyclosporine trough target level was 250–350 ng/ml during first 3 months, 100–250 ng/ml from 3 to 6 months and <100 ng/ml thereafter while C2 target level was 1000–1200 ng/ml during first 3 months and 600–1000 ng/ml thereafter. Prednisolone was tapered to 10 mg by the end of 3 months and 5 mg by the end of 6 months. Mycophenolate sodium was tapered to 360 mg twice daily by 6 months.

Protocol biopsy was performed at 3 months post-transplant for all ABOi renal transplant recipients. Graft biopsies were also performed whenever indicated such as in case of rising serum creatinine. All the graft biopsies were examined by light microscopy and immunofluorescence including C4d. All rejections were biopsy proven. Acute cellular rejection was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg od for three consecutive days).

Statistical analysis was done using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.7.8 (MedCalc Software, Belgium). Data were reported as mean values ± standard deviation. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired t-test while categorical values were compared using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

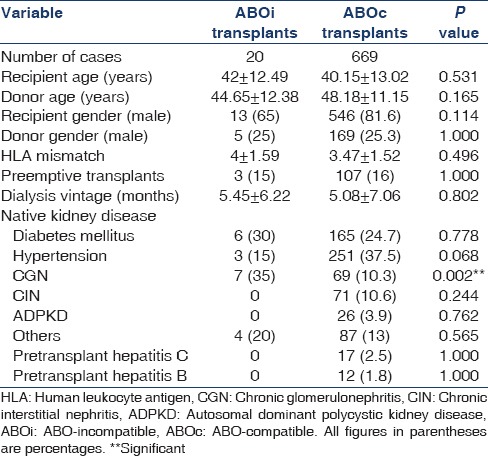

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 2 groups (i.e., ABOi and ABOc). Significantly more number of patients in ABOi group had chronic glomerulonephritis as the native kidney disease. Other demographic characteristics were comparable between the groups. One of the ABOi group patients was second transplant recipient. All the transplants in ABOi group were live related ones while in ABOc group 0.8% (n = 6) were deceased donor transplants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and clinical profile of patients

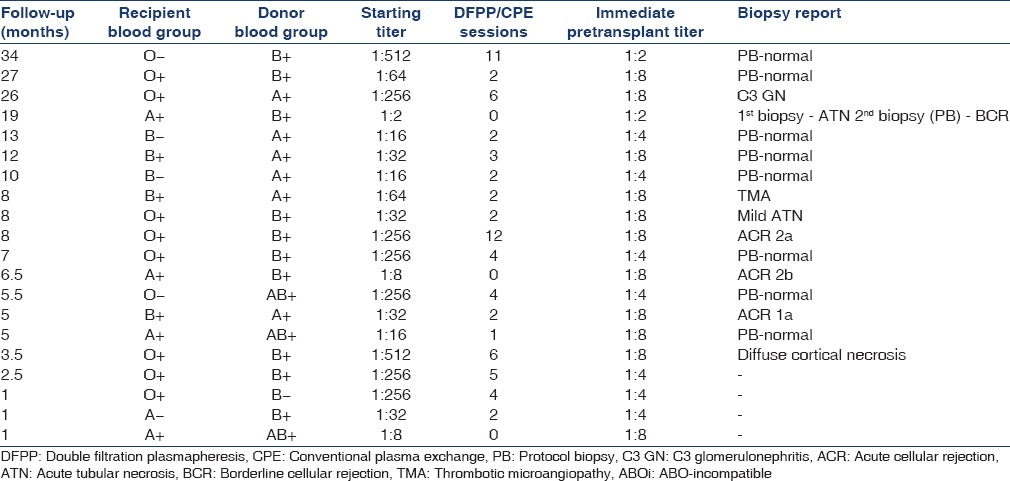

Table 2 shows the donor and recipient blood group distribution, starting antibody-titer and number of DFPP sessions required. It also shows the allograft biopsy details. The majority were O-blood group recipients (50%) followed by A and B (25% each). Most frequent titer was 1:256 (32%).

Table 2.

Blood group and titer distribution in ABOi group

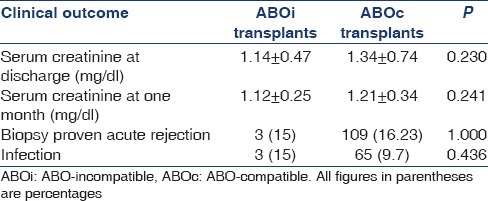

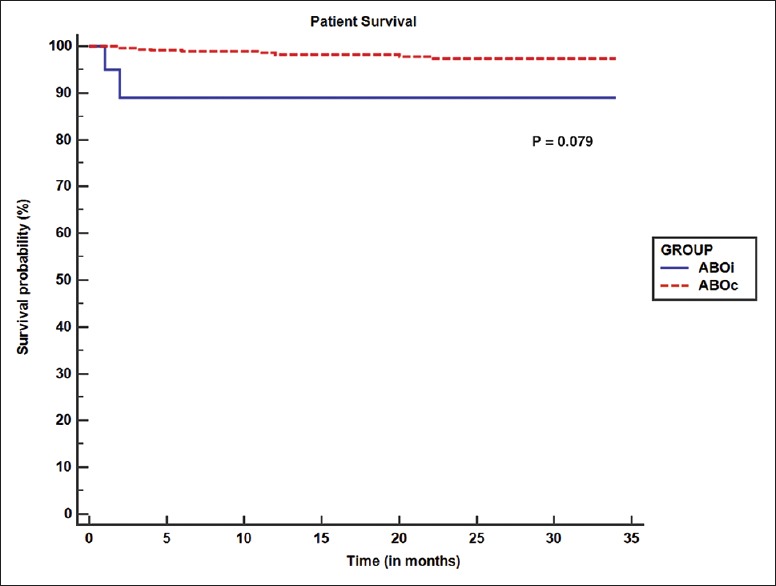

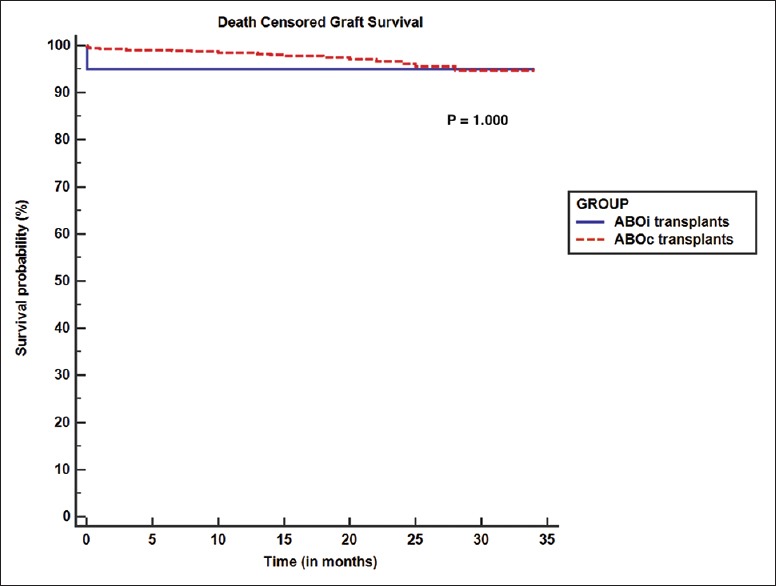

Recipient outcome is presented in Table 3. Mean duration of follow-up was 10.15 ± 9.34 months and 16.67 ± 9.63 months in ABOi and ABOc groups respectively. Patient and death censored graft survival was comparable between groups (P = 1). Figures 1 and 2 show Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patient and death censored graft survival between the two groups. Serum creatinine values at discharge and after 1-month were also comparable (P = 0.23 and 0.24 respectively). One patient died due to acute coronary syndrome. Although he had longstanding history of diabetes and hypertension, his pretransplant cardiac evaluation was normal. Another patient developed reduced urine output on the day of transplant. Graft biopsy showed thrombotic microangiopathy. There were no neutrophils or mononuclear cells in peritubular capillaries or glomeruli; neither there was any acute tubular injury. Staining for C4d in peritubular capillaries was negative. Repeat CDC and flow cytometry crossmatch was negative. Thrombotic microangiopathy was thought to be tacrolimus induced and hence it was withdrawn. He received plasma exchange sessions. He developed sepsis, which responded well to IV antibiotics. His renal functions and overall clinical condition started improving. Four weeks posttransplant, patient developed severe epigastric pain and recurrent bilious vomiting. Upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy showed hemorrhagic and necrotic ulcerative lesions in esophagus and stomach. Biopsy from these lesions revealed mucormycosis. Also, there was evidence of intranuclear inclusion bodies in gastric mucosa suggestive of CMV gastritis. He was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg/day) and intravenous ganciclovir (2.5 mg/kg/day). Later his abdominal pain worsened, and he developed refractory hypotension. Exploratory laparotomy was done which showed 3 cm × 3 cm rent in posterior wall of stomach. Distal gastrectomy along with debridement and feeding jejunostomy was done. But despite these measures, he succumbed to sepsis.

Table 3.

Recipient outcome

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier graph comparing patient survival between ABOi and ABOc group. (ABOi: ABO incompatible; ABOc: ABO compatible)

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier graph comparing death censored graft survival between ABOi and ABOc group. (ABOi: ABO incompatible; ABOc: ABO compatible)

On analysis, infection rates were not significantly different between the ABOi and ABOc groups (P = 0.16). BKV infection and pneumonia were seen in one patient each. As mentioned above, one patient had CMV infection and gastric mucormycosis.

A total of nine protocol and eight indication biopsies were done. Details of these biopsies are shown in Table 2. All protocol biopsies were normal. Staining for C4d was positive in 53% of cases. Of 8 patients whose biopsy was done for indication, two had delayed graft function. Of these, one had thrombotic microangiopathy as described above while another had diffuse cortical necrosis secondary to graft renal vein thrombosis. One patient had slow decline of serum creatinine in posttransplant period. In him, first renal biopsy showed acute tubular necrosis and protocol biopsy after 3 months showed borderline cellular rejection, which did not require any treatment, as renal function was stable. One of the patients developed nephrotic range proteinuria and active urine sediments. Graft renal biopsy showed C3 glomerulopathy. Her native kidney disease pretransplant was unknown. Her graft function is stable. Remaining 3 patients were biopsied for graft dysfunction. All had acute cellular rejections, which responded well to methylprednisolone pulse.

Discussion

In 1950s and 60s, initial attempts to do ABOi transplant in USA were met with high failure rate and very poor graft survival. It was concluded that ABO compatibility is a necessary prerequisite for successful renal transplant.[9,10,11] In 1987, Alexandre et al. showed that successful ABOi transplants with good graft outcome could be achieved using pretransplant desensitization (or preconditioning) protocol. He used plasma exchange to remove anti-A or anti-B antibodies and splenectomy to prevent further antibody production. Antilymphocyte globulin was used for induction.[12] Subsequently, large number of ABOi transplants was done in Japan using preconditioning protocol of plasma exchange and splenectomy with good graft and patient outcome.[13] Later, it was realized that chemical splenectomy using anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody-Rituximab can replace surgical splenectomy with good results[14] and splenectomy associated complications could be avoided. Most centers have now stopped doing splenectomy for ABOi transplant. The majority of the European centers have used immunoadsorption, IVIG and rituximab based protocols with good success.[15,16,17,18] In United States, Montgomery et al. have used rituximab, plasma exchange, and CMV IVIG as preconditioning.[19] Selective methods of antibody removal such as immunoadsorption and DFPP is being preferred these days as large plasma volumes can be processed, and risk of bleeding due to elimination of coagulation factors is minimized. Lately, in an effort to reduce overall immunosuppression, Flint et al. and Montgomery et al. have done ABOi renal transplants without rituximab in their protocols with good graft and patient survival outcome.[20,21] In our center, we have used preconditioning protocol of rituximab and conventional plasma exchange (5 patients)/DFPP (12 patients) followed by IVIG.

Patient survival was 90% in the current study. This was 98% and 100% in the study by Tydén et al., Flint et al. and Lipshutz et al. respectively.[16,20,22] Death censored graft survival of ABOi transplant group in our study was 95%. This is similar to the graft survival in the study by Tydén et al. (97%), Flint et al.(100%), and Lipshutz et al.(94.4%).[16,20,22] In the present study, death censored graft survival and patient survival of ABOi recipients were comparable to that of ABOc group. These findings are similar to that of study by Genberg et al.[15] In our study, serum creatinine at 1-month was similar between the 2 groups without any significant difference.

Rate of biopsy proven acute rejection was comparable between the groups. Biopsy proven acute rejection rate in ABOi recipients in the current study was 15%. This was better than the BPAR of 40% in a study by Wilpert et al. with similar immunosuppression protocol.[23] Lipshutz et al. reported BPAR of 11% in their ABOi recipients while it was 32% in a study by Uchida et al.[22,24] Most of the studies have reported higher incidence of antibody-mediated rejection in ABOi recipients, which has varied from 5 to 33%.[22,23,24,25] In our study, none of the ABOi recipients developed antibody-mediated rejection. Although one patient had TMA on biopsy, other features of AMR such as neutrophils or mononuclear cells in peritubular capillaries or glomeruli, acute tubular injury and C4d deposition in peritubular capillaries, were missing.[26] In addition, his renal function improved after stopping tacrolimus, which supported it to be drug induced TMA.

Graft biopsies showed C4d staining in 53% of cases. In various studies, C4d positivity in protocol graft biopsies has been seen in 80–94% of patients and does not necessarily indicate antibody-mediated rejection.[27,28] In fact, it may represent the phenomenon of accommodation, in which the graft continues to function normally despite the presence of anti-blood group antibodies.[28]

The infection rate in ABOi recipients was 15%, which was comparable to ABOc group. One ABOi patient developed CMV infection, and one had BKV infection. Most studies have shown a trend toward higher infection rate amongst ABOi transplant recipients, varying from 18 to 50%.[16,17,20,23]

There are some limitations of our study: The sample size of ABOi group is small. Also, the immunosuppression protocol was variable for ABOc group as mentioned in materials and methods. Follow-up of patients is short, and hence long-term outcome cannot be commented upon.

Concluding, published reports of ABOi transplant experience from developing countries are very few. Ours is one of the first such series. Graft and patient survival have been excellent in the current study. Rate of biopsy proven acute rejection was at par with ABO compatible ones and more importantly there were no antibody-mediated rejections. The incidence of posttransplant infections, which is a major concern in developing world, was acceptable and, in fact, lower than other similar studies. Our experience has been encouraging so far and proves that it is the right time for widespread implementation of ABOi transplants even in developing countries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chugh KS. Five decades of Indian nephrology: A personal journey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:753–63. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajapurkar MM, John GT, Kirpalani AL, Abraham G, Agarwal SK, Almeida AF, et al. What do we know about chronic kidney disease in India: First report of the Indian CKD registry. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segev DL, Gentry SE, Warren DS, Reeb B, Montgomery RA. Kidney paired donation and optimizing the use of live donor organs. JAMA. 2005;293:1883–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirakawa H, Ishida H, Shimizu T, Omoto K, Iida S, Toki D, et al. The low dose of rituximab in ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation without a splenectomy: A single-center experience. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:878–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toki D, Ishida H, Horita S, Setoguchi K, Yamaguchi Y, Tanabe K. Impact of low-dose rituximab on splenic B cells in ABO-incompatible renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2009;22:447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery RA. Renal transplantation across HLA and ABO antibody barriers: Integrating paired donation into desensitization protocols. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:449–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanabe K. Double-filtration plasmapheresis. Transplantation. 2007;84(12 Suppl):S30–2. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000296103.34735.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hume DM, Merrill JP, Miller BF, Thorn GW. Experiences with renal homotransplantation in the human: Report of nine cases. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:327–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI103085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Rifkind D, Holmes JH, Rowlands DT, Jr, Waddell WR, et al. Renal homografts in patients with major donor-recipient blood group incompatibilities. Surgery. 1964;55:195–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunea G, Nakamoto S, Straffon RA, Figueroa JE, Versaci AA, Shibagaki M, et al. Renal homotransplantation in 24 patients. Br Med J. 1965;1:7–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5426.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexandre GP, Squifflet JP, De Bruyère M, Latinne D, Reding R, Gianello P, et al. Present experiences in a series of 26 ABO-incompatible living donor renal allografts. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:4538–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanabe K. Japanese experience of ABO-incompatible living kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:S4–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000296008.08452.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tydén G, Kumlien G, Genberg H, Sandberg J, Lundgren T, Fehrman I. ABO incompatible kidney transplantations without splenectomy, using antigen-specific immunoadsorption and rituximab. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:145–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genberg H, Kumlien G, Wennberg L, Berg U, Tydén G. ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation using antigen-specific immunoadsorption and rituximab: A 3-year follow-up. Transplantation. 2008;85:1745–54. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181726849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tydén G, Donauer J, Wadström J, Kumlien G, Wilpert J, Nilsson T, et al. Implementation of a Protocol for ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation – A three-center experience with 60 consecutive transplantations. Transplantation. 2007;83:1153–5. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000262570.18117.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Agteren M, Weimar W, de Weerd AE, Te Boekhorst PA, Ijzermans JN, van de Wetering J, et al. The first fifty ABO blood group incompatible kidney transplantations: The Rotterdam Experience. J Transplant 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/913902. 913902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oettl T, Halter J, Bachmann A, Guerke L, Infanti L, Oertli D, et al. ABO blood group-incompatible living donor kidney transplantation: A prospective, single-centre analysis including serial protocol biopsies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:298–303. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery RA, Cooper M, Kraus E, Rabb H, Samaniego M, Simpkins CE, et al. Renal transplantation at the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center. Clin Transpl. 2003:199–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flint SM, Walker RG, Hogan C, Haeusler MN, Robertson A, Francis DM, et al. Successful ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation with antibody removal and standard immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1016–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery RA, Locke JE, King KE, Segev DL, Warren DS, Kraus ES, et al. ABO incompatible renal transplantation: A paradigm ready for broad implementation. Transplantation. 2009;87:1246–55. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819f2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipshutz GS, McGuire S, Zhu Q, Ziman A, Davis R, Goldfinger D, et al. ABO blood type-incompatible kidney transplantation and access to organs. Arch Surg. 2011;146:453–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilpert J, Fischer KG, Pisarski P, Wiech T, Daskalakis M, Ziegler A, et al. Long-term outcome of ABO-incompatible living donor kidney transplantation based on antigen-specific desensitization. An observational comparative analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3778–86. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchida J, Kuwabara N, Machida Y, Iwai T, Naganuma T, Kumada N, et al. Excellent outcomes of ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation: A single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:204–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toki D, Ishida H, Setoguchi K, Shimizu T, Omoto K, Shirakawa H, et al. Acute antibody-mediated rejection in living ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation: Long-term impact and risk factors. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:567–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Racusen LC, Haas M. Antibody-mediated rejection in renal allografts: Lessons from pathology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:415–20. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01881105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setoguchi K, Ishida H, Shimmura H, Shimizu T, Shirakawa H, Omoto K, et al. Analysis of renal transplant protocol biopsies in ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas M, Rahman MH, Racusen LC, Kraus ES, Bagnasco SM, Segev DL, et al. C4d and C3d staining in biopsies of ABO- and HLA-incompatible renal allografts: Correlation with histologic findings. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1829–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]