Abstract

Background:

Healthcare providers must be equipped to recognize and address patients' psychosocial needs to improve overall health outcomes. To give future healthcare providers the tools and training necessary to identify and address psychosocial issues, Lankenau Medical Center in partnership with the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine designed the Medical Student Advocate (MSA) program.

Methods:

The MSA program places volunteer second-year osteopathic medical students in care coordination teams at Lankenau Medical Associates, a primary care practice serving a diverse patient population in the Philadelphia, PA, region. As active members of the team, MSAs are referred high-risk patients who have resource needs such as food, employment, child care, and transportation. MSAs work collaboratively with patients and the multidisciplinary team to address patients' nonmedical needs.

Results:

From August 2013 to August 2015, 31 osteopathic medical students volunteered for the MSA program and served 369 patients with 720 identified needs. Faculty and participating medical students report that the MSA program provided an enhanced understanding of the holistic nature of patient care and a comprehensive view of patient needs.

Conclusion:

The MSA program provides students with a unique educational opportunity that encompasses early exposure to patient interaction, social determinants of health, population health, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Students develop skills to help them build patient relationships, understand the psychosocial factors shaping health outcomes, and engage with other healthcare professionals. This work in the preclinical years provides students with the knowledge to help them perform more effectively in the changing healthcare environment.

Keywords: Community health services, education–medical–undergraduate, health services needs and demand, healthcare disparities, patient care team, primary health care, social determinants of health

INTRODUCTION

Socioeconomic status and other social determinants have been shown to have a powerful impact on health outcomes.1 McGinnis et al report that an estimated 40% of premature deaths can be attributed to behavioral patterns, 30% to genetics, 15% to social circumstances, and 5% to the environment, while only 10% of premature deaths are directly attributable to medical care.1 To address these trends, healthcare must evolve from diagnosis-specific interventions that react to a medical problem to more holistic, proactive care that focuses on the comprehensive needs of patients—both medical and social. Upstream preventive measures focused on behavioral, social, and environmental determinants are necessary to improve long-term health outcomes. Social determinants are often the root causes of illnesses and are key to understanding and addressing health disparities.2

Lankenau Medical Associates (LMA), a National Committee for Quality Assurance Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Level 3–recognized practice, is located on the border of Montgomery County and Philadelphia County, PA. LMA is an internal medicine and subspecialty residency practice at Lankenau Medical Center (LMC)—part of Main Line Health—that is focused on care of the underserved. The majority of LMA patients reside in West Philadelphia. More than 46% of patients at LMA have Medicaid-based insurances, and 26% are uninsured. More than 60% of the adults in the LMA West Philadelphia service area (zip codes 19151, 19131, and 19139) report difficulty making housing payments, and >20% report reducing their meal size or skipping meals because of cost.3 Among the uninsured, 35% report that cost is a major barrier to healthcare.3 Socioeconomic factors such as income, educational attainment, access to food and housing, and employment status have a profound impact on health. In fact, these nonmedical factors account for as much as 40% of health outcomes.4 Because they struggle to meet basic needs, many patients in the practice have comorbid diagnoses and chronic diseases that become increasingly difficult to manage as they try to overcome nonmedical barriers to care.

A recent trend in healthcare is the move toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach to meet the medical and psychosocial needs of patients.5 LMA recognized the need to transition into delivering team-based care for patients to improve health outcomes and created PCMH teams to provide a weekly multidisciplinary forum for care coordination and population health management. PCMHs offer an important opportunity to promote population health through systematically addressing the social determinants of health.6 PCMH teams comprise an interdisciplinary group of healthcare workers—physicians, nurses, and social workers—who coordinate care to help identify patients' basic resource needs and address barriers to healthcare and health access. By leveraging the expertise of a diverse group of health professionals, a wide range of health determinants can be addressed.

In an effort to increase the capacity of the PCMH teams, alternative models for staffing were explored. As an academic medical center, LMC has strong partnerships with local medical schools and a desire to engage students early in their education process. To provide a comprehensive educational experience that embeds public health and population health management, LMC in partnership with the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (PCOM) developed the Medical Student Advocate (MSA) program. In this high-quality, low-cost model, volunteer, unpaid medical students are members of an interprofessional PCMH team and address the complex socioeconomic issues facing high-risk patients. Second-year medical students learn essential skills to counsel patients, communicate with healthcare workers, and collaborate with an interprofessional team in caring for patients.

METHODS

All first-year students enrolled in the PCOM doctor of osteopathic medicine program were eligible to apply to the MSA program. Applicants were asked to submit a resume and brief application consisting of 4 short responses: 2 prompts drawing on personal experience and 2 mock case scenarios eliciting brief analysis. A diverse selection committee, including graduate medical education leaders, primary care providers, care coordination experts, social workers, and case managers selected candidates based on their applications, ensuring that their academic standing (as documented by the Office of Academic Affairs) would not be jeopardized by their volunteer commitment to the MSA program. In the 2013-2014 academic year, 8 students were selected to participate in the MSA program. Given the success of the pilot class, 12 students were selected in the 2014-2015 academic year. A pilot summer program with 4 students was offered in 2015, and 11 students have been selected to participate in the 2015-2016 academic year (4 of whom participated in the summer program).

The overall cohort of 31 MSAs was diverse with regard to previous work experience, sex, age, and race. MSAs completed a survey (94% response rate) requesting demographic data related to sex, race, and ethnicity; age entering the MSA program; and previous work experience. MSAs had an average age of 26 years; the oldest student entering the MSA program was 36 years, and the youngest was 23 years. Fifty-eight percent of the students were female, and 42% were male. Seventeen percent identified as Asian, 4% identified as black/African American, and 79% identified as white. All survey respondents identified as non-Hispanic. Many MSAs had taken time off between obtaining an undergraduate degree and beginning medical school, with 86% having had work experience before starting PCOM. Fifty-five percent of MSAs entered the program with no public health experience, and 45% had public health experience ranging from participation in a medical mission to the acquisition of a master of public health degree.

Once selected, students assumed their roles as MSAs at the start of their second year of medical school and continued volunteering throughout the academic year, August to April. Prior to beginning their work with patients, all students participated in a 2-day orientation focused on developing communication skills and honing cultural competency through lectures, role-playing exercises, and group discussion. In addition, students were given an overview of the patient population served by LMA and a detailed explanation of the PCMH model. As part of orientation, students received a list of approximately 250 resources to address commonly identified patient needs and tools to assist them in locating additional resources as needed.

MSAs were assigned to 1 of 4 PCMH teams comprised of nurses, social workers, nurse practitioners, health educators, physicians, and medical assistants. This model served as a core component of the LMA approach to patient-centered care. Each week, the PCMH teams met to coordinate patient care. The teams reviewed patients who met specific high-risk criteria including multiple comorbidities, known gaps in preventive care, and recent hospitalization or emergency room visit. In September 2014, LMA introduced the Social Needs Survey, a new mechanism for patients to identify and communicate their resource needs. All patients at LMA received the survey form at the time of registration. Patients who completed the survey were reviewed at a PCMH team meeting dedicated specifically to addressing psychosocial needs. Patients were triaged to social workers, health educators, case managers, or an MSA for follow-up.

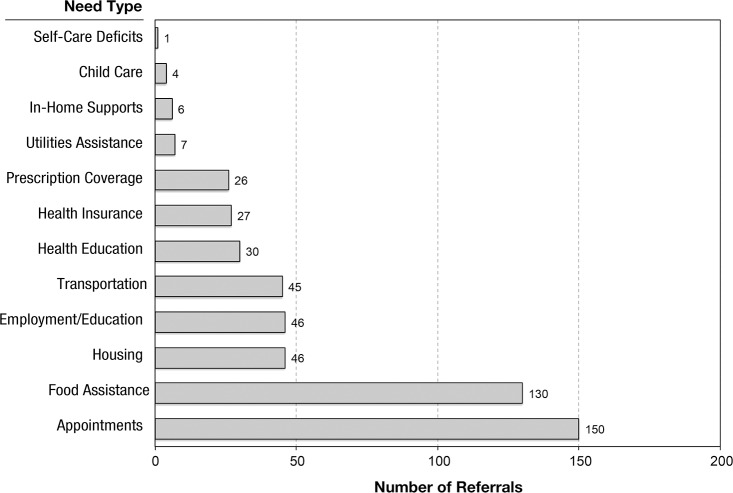

MSAs addressed a range of nonmedical patient needs including transportation, child care, food access, and utilities assistance (Figure). When a referral was made to an MSA, the assigned advocate contacted the patient via telephone. The initial conversation involved an assessment of the patient's needs and existing supports; thereafter, students worked collaboratively with the patient and the PCMH team to address the identified concerns. MSAs researched available community resources and provided needed referrals. When possible, students were encouraged to develop longitudinal relationships and address multiple needs with their patients.

Figure.

Medical student advocate referrals from August 2014 to August 2015.

In addition to the weekly PCMH team meetings, MSAs attended weekly reflection sessions facilitated by the program administrator, a licensed social worker. These sessions provided an opportunity to discuss difficult cases and to share best practices. Professionals from Main Line Health and community organizations were invited to attend the sessions and provide education on relevant topics such as Medicaid expansion, community services, and motivational interviewing.

All participating students consented to videotape 2 reflection sessions. Reflection sessions were informal gatherings for comments and feedback. The intents of videotaping the reflection sessions were to facilitate recruitment of future MSAs, provide an overview of the program, and support project continuity by demonstrating to future volunteers how the MSAs spent their time.

The MSA program provided an opportunity for experiential learning for medical students, while also serving as a quality improvement project for LMA. We had no intention to analyze results, so we did not seek institutional review board approval.

RESULTS

From August 2013 through August 2015, 3 classes of MSAs totaling 31 second-year osteopathic medical students participated in the MSA program. The first cohort of students served an individual average caseload of 5 active patients. The second group of students had an average caseload of 15-20 active patients with approximately 1-2 social needs per patient. The third cohort of students who participated in the summer had an average of 10-15 active patients with approximately 1-2 social needs per patient. When a patient's issues were addressed successfully, and closure was achieved, the MSA was assigned a new patient. A large majority of patients were referred to the program after they identified a psychosocial need on the Social Needs Survey. Since the program's inception in August 2013, 31 MSAs have served 369 patients with a total of 720 identified needs. Of the 720 identified needs, 233 were successfully resolved by MSAs by connecting patients to community-based resources, 37 were referred internally to other members of the PCMH team (social work and case management), and 218 are still open and being actively addressed by MSAs. We cannot confirm resolution of the remaining 232 needs in the context of our practice. Many of these needs, such as housing and employment, remain unresolved because of public policy and community infrastructure challenges. Programs that help people get an education, find employment to lift a family out of poverty, or provide stable housing are hard to find, and social programs like these have become increasingly vulnerable,2 limiting the ability of the MSAs to make appropriate resource connections.

Patients in the program had an average of 2 major identifiable needs. The most commonly addressed issues were (1) lack of preventive care such as mammography, colonoscopy, diabetes screenings, and women's health; (2) adherence to follow-up appointments; and (3) food insecurity. Other frequently encountered issues included lack of transportation, housing, and employment.

In addition to addressing the resource needs of their active patient caseload, these medical students focused on special projects to enhance the program. One such project was the expansion of the wiki page resource compendium. In linking patients to community resources, students, through their own initiative, expanded their original online list of resources from approximately 250 to nearly 600 regional resources. This list was developed and maintained as a wiki page, and this valuable compilation of resources was ultimately shared with other healthcare providers in the Main Line Health system.

Students who participated in the program reported increased empathy toward patients and demonstrated an understanding of the social determinants of health and their impact on health outcomes. During reflection sessions, students shared that they felt more confident entering their third-year clerkships because they had had ample interactions with patients during the MSA program. During their clerkships, students continued to use the skills they developed in the MSA program to connect patients with resources, including transportation and prescription assistance programs.

The consensus of the student participants was that the MSA program provided them with 3 key educational opportunities: (1) preclinical patient interaction, (2) exposure to the social determinants of health and population health management, and (3) participation in an interdisciplinary team.

DISCUSSION

Patient Interaction

Participation in the MSA program provided students with exposure to patient interaction early in their medical education. Through these relationships, students had the opportunity to develop cultural competency and empathy for patients from varying socioeconomic backgrounds and cultures. One student noted, “It definitely helped me get a better understanding of people from different walks of life. If you look at the demographic of the average medical student, we come from privilege. It's really easy to lose sight of what you're trying to do in medicine when you don't really understand whom you're doing it for” (videotaped November 10, 2014, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 1). A 2011 study by Hojat et al showed that physician empathy is not only associated with patient satisfaction but also with positive clinical outcomes.7 By allowing the MSAs to interact with patients early in their medical training to address nonmedical needs, the students' perspectives on the scope of patient care widened to include the entire individual, rather than just his or her symptoms. Another MSA commented, “[Patients] just need someone to be on their side, to be on their team and take that extra step” (videotaped November 10, 2014, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 2). The MSA program equipped students with social skills and insight that can help them as future physicians build effective relationships with their patients. An MSA alumna in her third-year clerkship commented, “I know how to help the patient. I felt really empowered, and I actually contributed to the team, which is sometimes hard as a student” (videotaped February 23, 2015, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 3.

Exposure to the Social Determinants of Health and Population Health Management

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, determined that Philadelphia County is the least healthy county in Pennsylvania, ranking 67th of 67.8 The ranking considers overall health outcomes, including premature death; health behaviors such as lack of exercise, smoking, and obesity; clinical factors such as percentage of uninsured individuals; and socioeconomic factors such as poverty, lack of access to healthy foods, crime, and education levels.

Accordingly, the MSAs were faced with a breadth of patient needs and gained an appreciation for the numerous nonmedical factors impacting patient health. MSAs acquired insight into some of the barriers impeding the health of low-income populations. While reflecting on the program, a student commented that her perception of patient compliance has been transformed: “You find out that [patients don't take their medication because] they don't have money for it or they couldn't get to the pharmacy. If you help them address those issues then they're more likely to take their medication” (videotaped November 10, 2014, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 4). Another MSA added, “You find that [patients'] issues can be so much more complex than you thought they would be” (videotaped November 10, 2014, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 5). By working one on one with patients, the MSAs were afforded a glimpse into these social determinants and grasped how these factors translated to long-term health outcomes. This insight was reflected in another MSA's comments, “People want to be healthy. They want to take care of their health, so helping them address nonmedical needs in order to have better care has been really great for me and good for the patients” (videotaped November 10, 2014, 2013-2014 class, MSA participant 6).

Interdisciplinary Cooperation

The MSA program endeavors to introduce medical students not only to patient interaction but also to working relationships with other healthcare professionals. As part of a PCMH team, MSAs were active participants in providing comprehensive patient care and gained experience in recognizing the value of coordinated teamwork. As healthcare continues to evolve, physicians face increasing time constraints with patients and must learn to rely on other professionals to assist with meeting patient needs. For a successful practice, physicians must feel comfortable working with a team and receive training in interdisciplinary collaboration. A 2014 study showed that students had more rewarding interprofessional experiences when they directly interacted with people from disciplines outside of their own rather than receiving formal instruction from them in the form of lectures.9 The value of interdisciplinary collaboration was demonstrated in the MSA comment, “Social work, nursing, and physicians come together and add their skill sets and their backgrounds to the patient. And that's where medicine is going” (videotaped February 23, 2015, 2014-2015 class, MSA participant 7). When MSAs were faced with a challenging patient need, the PCMH team provided a safe environment to develop new ideas and seek advice from experienced healthcare professionals. Through actively addressing real-life problems, students developed a deep appreciation of the scope of primary care in addition to a thorough understanding of the roles of other health professionals.

To better align with the evolving model of healthcare, medical education curricula must include training in recognizing and addressing the social determinants of health.10 Increasing physician knowledge regarding psychosocial issues and equipping students with the tools necessary to discuss barriers to care and compliance with therapeutic regimens have the potential to improve the health disparities facing vulnerable populations.10

Future of the MSA Program

Embedding methods to address social determinants of health within a PCMH represents a high-value benefit to the health system and provides an avenue to reduce socioeconomic disparities in healthcare.6 Looking forward, Main Line Health intends to expand the MSA program to address more patients' unmet social needs and to enrich medical student education for a greater number of students. Additionally, the health outcomes data from the patients served by the MSA program from 2013-2015 will be analyzed, and the impact of adding an MSA to the PCMH team will be assessed. The students will continue to document their follow-up in the electronic medical record so that patient outcomes can be monitored. We have plans to expand the program to other practices in the Main Line Health system and to develop a partnership with a federally qualified health center in West Philadelphia. Collaboration with the emergency department at LMC is underway to investigate whether unnecessary emergency department visits can be curtailed by greater attention to nonmedical barriers.

CONCLUSION

The MSA program provides students with a unique educational opportunity that encompasses early exposure to patient interaction, social determinants of health, population health, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Students develop skills to help them build patient relationships, understand the psychosocial factors shaping health outcomes, and engage with other healthcare professionals. This work in the preclinical years provides students with the knowledge that can help them perform more effectively in the changing healthcare environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge John Lynch, III, CEO of the Main Line Health system, Phillip Robinson, president of Lankenau Medical Center, and Dr Kenneth J. Viet, dean of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine for their support of this program.

The authors appreciate the editorial assistance provided by Judy Spahr and would like to thank the inaugural Medical Student Advocate class: Nicole Anand, Laura Deschamps, Laurel Garber, Laura Hackenberger, Jenna Landers, Devin McKelvey, Alexa Namba, and Justin Ross.

This program was funded, in part, by the Pennsylvania Department of Health Community-Based Health Care Program and the Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation.

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Professionalism, and Systems-Based Practice.

REFERENCES

- 1. . McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002. Mar-Apr; 21 2: 78- 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. . Woolf SH, Braveman P. Where health disparities begin: the role of social and economic determinants—and why current policies may make matters worse. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011. October; 30 10: 1852- 1859. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. . Public Health Management Corporation Community Health Data Base. Southeastern Pennsylvania household health survey . http://chdb.phmc.org/datatool/popselect.asp. Updated 2012. Accessed August 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. . The Commonwealth Fund. Addressing patients' social needs: an emerging business case for provider investment . http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/may/addressing-patients-social-needs. Accessed November 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. . Everett C, Thorpe C, Palta M, Carayon P, Bartels C, Smith MA. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners perform effective roles on teams caring for Medicare patients with diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013. November; 32 11: 1942- 1948. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. . Garg A, Jack B, Zuckerman B. Addressing the social determinants of health within the patient-centered medical home: lessons from pediatrics. JAMA. 2013. May 15; 309 19: 2001- 2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. . Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians' empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011. March; 86 3: 359- 364. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. . Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps . http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/pennsylvania/2015/rankings/outcomes/overall. Updated 2015. Accessed August 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. . Gilligan C, Outram S, Levett-Jones T. Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014. March 18; 14: 52 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. . Awosogba T, Betancourt JR, Conyers FG, et al. Prioritizing health disparities in medical education to improve care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013. May; 1287: 17- 30. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]