Abstract

Background

Anger and problematic alcohol use have been established as individual risk factors for intimate partner violence (IPV) victimisation and perpetration, but it is unknown how these factors convey risk for IPV perpetration for men and women within the context of mutually violent relationships.

Hypotheses

Anger and problematic alcohol use were hypothesised to mediate the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration for men and women, with direct and indirect influences from partner variables.

Methods

Heterosexual couples (N = 215) at high-risk for IPV completed questionnaires indexing trait anger, problematic alcohol use and extent of past-year IPV perpetration and victimisation. An actor-partner interdependence modelling (APIM) framework was used to evaluate these cross-sectional data for two hypothesised models and one parsimonious alternative.

Results

The best-fitting model indicated that IPV victimisation showed the strongest direct effect on physical IPV perpetration for both men and women. For women, but not men, the indirect effect of IPV victimisation on physical IPV perpetration through anger approached significance. For men, but not women, the victimisation–perpetration indirect effect through problematic drinking approached significance.

Implications for clinical practice

The results suggest that anger and problem drinking patterns play different yet important roles for men and women in mutually violent relationships.

Physical and psychological forms of IPV victimisation are associated with serious negative psychological and physical outcomes to survivors (Lawrence et al., 2012). Studies indicate that physical and psychological IPV victimisation are robust predictors of perpetrating physical aggression toward that same partner (Stith et al., 2004; Finkel et al., 2009). Relationship dynamics, as important contextual information, may exert a transactional influence on how individual risk factors for IPV perpetration convey risk for one partner relative to the other. The current study examines the roles of two individual-level, aggressogenic factors (i.e. anger and problematic alcohol use) as mediators of the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration in the context of a mutually violent romantic relationship using an actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) to investigate partner-dependent relationships.

A meta-theoretical model for IPV perpetration

Many theoretical models for IPV perpetration emphasise broad categories of risk factors or distal levels of analysis (e.g., feminist/cognitive behavioural theories). We propose a more parsimonious framework that not only outlines risk factors for IPV perpetration but also establishes the fundamental processes (and their interaction) that are necessary and sufficient for IPV to occur. The I3 meta-theoretical model for IPV perpetration argues that the likelihood of partner conflict is best conceptualised in terms of process factors, or the combination of instigating triggers, impelling influences and disinhibiting factors for given individuals in specific contexts (Finkel, 2007; Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). It thus offers a parsimonious explanation of whether, how and for whom specific risk and protective factors for IPV exacerbate or mitigate aggression likelihood.

Instigation: IPV victimisation

Instigation provides critical information regarding the context and whether a person experiences, in that moment, an urge to behave aggressively. Comprehensive reviews of the literature (Capaldi et al., 2012), as well as laboratory studies (e.g. Finkel et al., 2009; Slotter et al., 2012), indicate that physical IPV victimisation exerts a large effect on one’s own IPV perpetration (Stith et al., 2004; Crane and Eckhardt, 2013). Those in high-risk relationships characterized by bi-directional IPV likely face frequent and intense provocation toward aggressive behaviour, with other impelling, inhibiting and disinhibiting factors moderating the likelihood that aggressive urges result in IPV perpetration.

Impeller: anger

Impelling factors exacerbate an urge toward aggression perpetration. Male and female IPV perpetrators show a greater propensity to experience anger across situations and express anger outward relative to nonviolent individuals (Barbour et al., 1998; Capaldi et al., 2012; Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015). Intense experiences of anger on a given day increase the likelihood for subsequent IPV aggression perpetration in men and women (Crane and Eckhardt, 2013; Elkins et al., 2013), with women’s anger being a somewhat stronger predictor of IPV perpetration (Crane and Testa, 2014). As such, dispositional anger likely acts as an impelling mediator of the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration.

Disinhibitor: alcohol use

Disinhibiting factors decrease the likelihood that a person will resist aggressive urges. Alcohol use disorders are strongly associated with IPV perpetration(Smith et al., 2012) and researchers have identified a high co-occurrence of substance use disorders among male and female IPV perpetrators (Coker et al., 2002; Stuart et al., 2003; Lawrence et al., 2012; Slep et al., in press). Problematic drinking predicts IPV perpetration among husbands and wives in newlywed studies (Testa et al., 2003), and intoxicated individuals are less likely to inhibit aggressive urges and are at greater risk for conflict on days in which they engage in heavy drinking (Eckhardt, 2007; Crane et al., 2014). Thus, problematic alcohol use likely acts as a disinhibiting mediator of the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration.

Current study

The current study is the first to examine whether anger and problematic alcohol use mediate the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration for men and women in mutually violent relationships. Given the clear evidence of the bidirectional nature of IPV (Archer, 2000; 2002; Desmarais et al., 2012), it is important to account for the reciprocal nature of conflict in close relationships by examining how each partner’s anger and problematic alcohol use influences their partner’s behaviour. Thus, using a cross-sectional dataset of mutually violent couples and the I3 model of IPV, we conceptualised the interactive associations among these variables within an Actor Partner Interdependence Model framework (APIM; Cook and Kenny, 2005). The APIM allowed for simultaneous analysis of individual and partner predictors of IPV perpetration while accounting for the interdependence of actor and partner variables.

In all analyses, IPV victimisation, as an instigating factor (Stith et al., 2004), was predicted to have a direct effect on IPV perpetration. Anger, as an impelling influence, was expected to partially mediate the association between IPV victimisation and perpetration as indicated by a significant indirect effect of IPV victimisation on perpetration through anger. Additionally, our analyses examined two potential indirect pathways in which problematic alcohol use may disinhibit physical IPV perpetration from victimisation in the context of the APIM. One hypothesised pathway predicted a direct effect of partner problematic alcohol use on actor IPV perpetration (e.g. Testa et al., 2003). An alternative pathway examined whether actor drinking had a direct effect on partner drinking in a feedback loop, given prior research findings regarding discrepancies in drinking patterns and relationship conflict. A third, parsimonious model was also tested in which all partner effects were removed in order to evaluate the utility of an actor–partner structural model.

Method

Participants

Heterosexual couples (N = 391) were recruited from urban communities in the Midwest and Southeast United States for a larger study examining alcohol use and IPV. Participants were recruited using print and online advertisements. Eligible couples were in a romantic relationship lasting at least one month. To qualify for the larger study which involved alcohol administration, respondents were required to be generally healthy (absence of medical problems, no current psychiatric diagnosis, no involvement in treatment for a psychological or relationship disturbance). In addition, at least one member of the couple must have consumed an average of at least five (for men) or four (for women) or more standard drinks per occasion in the past year and consumed alcohol at least twice a month. Application of these criteria excluded 62 couples. Individuals who indicated that they had perpetrated severe forms of physical aggression against their partners (e.g. used a knife or gun on a partner, etc.) during a phone interview were deemed ineligible for this study due to safety concerns complicated by alcohol intoxication in the larger study. However, couples in which one partner perpetrated minor physical IPV and their partner perpetrated severe physical IPV were permitted to participate in the questionnaire portion of the project. This resulted in a selective and disproportionately smaller subset of severe physical IPV perpetrators (23%) in the final sample of the current study.

The current investigation required that both members report at least one act of minor physical IPV toward their partner according to the Physical Assault subscale on the Revised Conflict Tactics scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996). This criterion excluded 106 couples in which only one partner self-reported physical IPV perpetration. Additionally, eight couples were excluded from analysis due to missing data. The final sample consisted of 215 couples (see Table 1). Participants were compensated $10 per hour of participation. This study was approved by each university’s institutional review board.

Table 1.

Demographic data for the sample at the individual level

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 32.73 (10.49) |

| Race (%) | |

| African American | 63.7 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.2 |

| Asian American | 1.4 |

| European American | 27.7 |

| More than one race | 6.3 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic or Non-Latino | 95.1 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Single (never married) | 42.6 |

| Not married/living with partner | 32.8 |

| Married | 15.6 |

| Divorced | 6.7 |

| Separated | 2.1 |

| Widowed | 0.2 |

| Mean years of education (SD) | 13.99 (2.53) |

| Annual income (%) | |

| $0–5000 | 20.7 |

| $5001–10 000 | 15.9 |

| $10 001–20 000 | 24.5 |

| $20 001–30 000 | 17.0 |

| $30 001–40 000 | 11.0 |

| $40 001–50 000 | 5.4 |

| $50 001 + | 5.3 |

Note: Demographic statistics are based on the following sample sizes due to missing data at the individual level: age (n = 429); race (n = 427); ethnicity (n = 429); marital status (n = 430); years of education (n = 424); annual income (n = 429). SD = Standard Deviation.

Measures

Trait Anger Scale (Spielberger, 1988)

This 10-item subscale of the well-validated State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory assesses both (1) the tendency of a person to experience and express anger across a variety of situations, and (2) disposition to experience anger in response to the perception of personal injustice. Higher scores indicate more intense anger experiences. Internal consistency in the current sample was high (α = .86).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 2001)

This 10-item measure assesses the extent of problematic alcohol use, with higher scores indicating more hazardous use patterns. Total scores of 8 and above indicate hazardous drinking patterns and predict negative consequences, while scores above 16 indicate a high probability of an alcohol use disorder (Conigrave et al., 1995).

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996)

The 78-item CTS2 consists of five subscales: (1) Negotiation; (2) Psychological Aggression; (3) Physical Assault; (4) Sexual Coercion and (5) Injury. Items alternate phrasing so that an act is described first as being perpetrated by the respondent against their partner and the following item then describes the victimisation by the respondent’s partner (e.g. ‘I shouted or yelled at my partner’ then ‘My partner shouted or yelled at me’). Of relevance to this investigation, the Physical Assault subscale (α = .86) containsminor and severe physically aggressive acts (e.g. ‘I slapped my partner’ or ‘I choked my partner’). The Psychological Aggression subscale (α = .79) contains mild and severe non-physical acts that are emotionally abusive and controlling (e.g. ‘I insulted or swore at my partner’ or ‘I called my partner fat or ugly’).

We used a variety scoring method to calculate subscale scores (e.g. Moffitt et al., 1997) by tallying the number of different acts of physical and psychological IPV perpetration and/or victimisation in the past 12 months. A variety scoring approach is advantageous as it (1) tends to be less skewed (Elliott and Huizinga, 1989), (2) places equal weight on less frequent, but more severe forms of IPV, and more frequent, but less severe forms of IPV and (3) is more reliable because of the relative ease to recall whether an act occurred compared to its frequency. Variety-scored Actor’s self-reported victimisation items of the Physical Assault and Psychological Aggression subscales were summed to create a Total IPV Victimisation score, with higher scores indicating more frequent IPV victimisation. The same method used Actor’s self-reported perpetration items to create the Physical IPV Perpetration score, with higher scores indicating more frequent IPV perpetration.

Procedures

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants individually provided informed consent and completed a screening battery to confirm their eligibility. Participants then completed a second battery of computer-administered questionnaires in separate rooms using MediaLab 2006 software (Jarvis, 2006).

Data analyses

All couples included in the analyses had complete data. Hypothesised models were tested using path analytic techniques in Mplus v7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2013) with an APIM framework. Three path models were tested and compared using maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation. Variables for male and female partners were modelled separately within each model in order to account for data interdependence (Kenny et al., 2006). Model fit was determined using a non-significant χ2, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values above .95, root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value close to .06, and standardised root-mean squared residual of below .08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

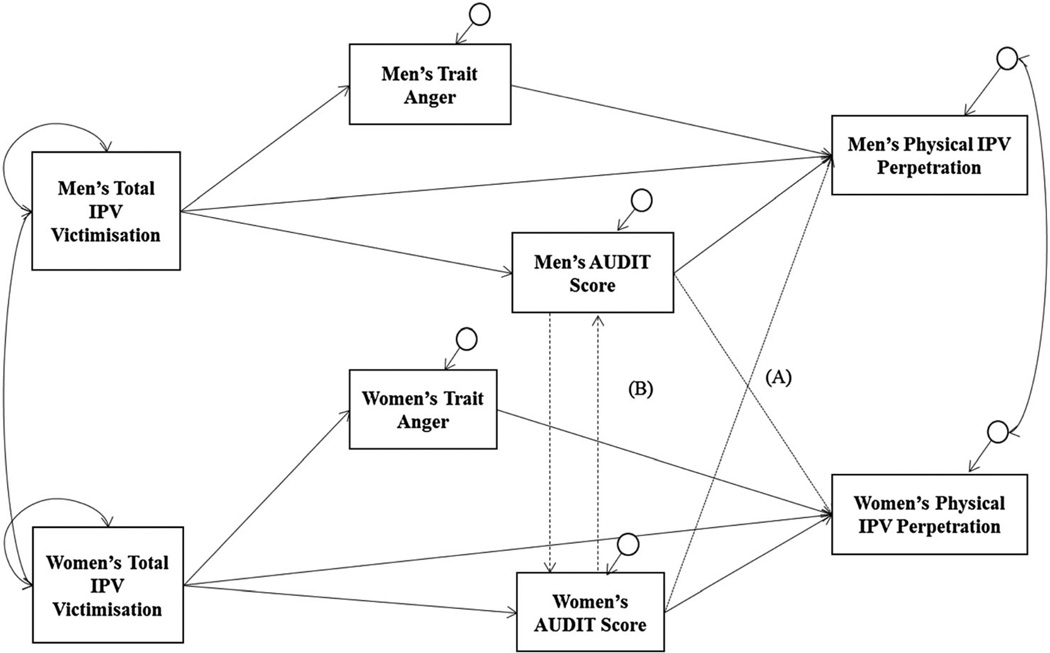

The first model (Figure 1) estimated a direct path between IPV victimisation and IPV perpetration. Anger and problematic drinking were anticipated to partially mediate this association. Direct partner effects for problematic alcohol use on actor IPV perpetration were also modelled. Models for men and women in each couple were computed simultaneously and path estimates were permitted to vary across sex. Residuals of IPV victimisation for men and women were allowed to covary because unmeasured factors likely have mutual influence on victimisation likelihood (e.g. environmental stressors and psychopathology). Also, the residuals for physical IPV perpetration across sex were allowed to covary, as they both may be affected by unmeasured aggressogenic influences.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised models. For Model 1, anger and problematic alcohol use partially mediate the association between IPV victimisation and IPV perpetration (solid lines), with (A) partner problematic alcohol use as direct effect on actor IPV perpetration (dotted lines). Model 2 tests the same partial mediating pathways for anger and alcohol use, but presents (B) a feedback loop for partner drinking on actor drinking (dashed lines) instead of direct effects on partner IPV perpetration. Model 3 removes all partner influences and tests a parsimonious model for comparison (solid lines only)

The second model tested an alternative hypothesis for the role of a partner’s alcohol use on an actor. Heavy drinking has not always been shown to directly contribute to risk of IPV perpetration, so a model was investigated in which actor problem drinking was associated with the partner’s problematic drinking in a feedback loop. In this second model, the paths among the variables remained the same as in the first, with the exception that problem drinking for men and women now has a direct feedback loop such that the man’s alcohol use is estimated to influence his female partner’s alcohol use and vice versa. Covariances from the first model were retained in the second. In order to examine the relative fit of APIM models to our dyadic data, the above models were compared to a more parsimonious model in which actor–partner effects were removed. This comparison permits the evaluation of the appropriateness of more complex APIM models relative to a simpler configuration.

Results

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. No mean differences were observed across sex for trait anger or physical IPV perpetration. Significant differences were observed across sex for IPV victimisation and problematic alcohol use, such that men experienced more IPV victimisation and reported more problematic drinking. Significant correlations were observed between all study variables for men and for women. IPV victimisation and perpetration variables were highly correlated for both sexes. Problematic drinking and trait anger were more highly correlated for women, r = .37, relative to males, r = .17, z-score = 2.23, p < .05.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for trait anger, AUDIT score, total intimate partner violence (IPV) victimisation, and physical IPV perpetration for men and women.

| Variable | Men M (SD) |

Women M(SD) |

t | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trait anger | 19.15 (5.87) | 19.20 (6.23) | 0.09 | (—) | .17* | .30** | .27** |

| 2. AUDIT total score | 10.63 (6.82) | 8.22 (6.21) | 3.84** | .37** | (—) | .29** | .31** |

| 3. Total IPV victimisation | 6.46 (3.82) | 5.60 (3.86) | 2.32* | .30** | .28** | (—) | .70** |

| 4. Physical IPV perpetration | 2.33 (1.76) | 2.58 (2.21) | 1.30 | .34** | .25** | .76** | (—) |

Note: Bivariate correlations below the diagonal are for women and above the diagonal are for men. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; SD = Standard Deviation. Intimate partner violence (IPV) victimisation and perpetration scores are represented as variety scores indicating the number of different IPV perpetrated against or received from a partner in the past year.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Path models

Model 1 fit to the data was acceptable (Table 3). As predicted, the direct path between IPV victimisation and IPV perpetration was significant for both men and women. Similarly, the direct path between IPV victimisation and trait anger was significant for both sexes. However, for women, but not men, the path between trait anger and IPV perpetration was significant and the indirect effect of IPV victimisation on physical IPV perpetration through trait anger approached significance, β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p < .10. The direct path between IPV victimisation and problematic alcohol use was significant for both men and women. For men, but not for women, the path between problematic alcohol use and men’s IPV perpetration was significant and the indirect effect of IPV victimisation on physical IPV perpetration through problematic alcohol use approached significance, β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p < .07. The actor–partner effects linking problematic alcohol use to IPV perpetration were non-significant for men and women. The hypothesised covariance between men’s and women’s IPV victimisation was significant.

Table 3.

Model fit indices

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Partner problematic alcohol Use influencing actor IPV perpetration | 43.95* | 13 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.11 (0.07–0.14) | 0.07 | ||

| 2. Direct feedback loop for actor-partner problematic alcohol use | 42.81* | 14 | 9.84* | 1 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.10 (0.07–0.13) | 0.06 |

| 3. Without actor-partner effects | 81.73* | 16 | 39.86** | 2 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.14 (0.11–0.17) | 0.09 |

Note: χ2 = χ-squared statistic; df = degrees of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis Index; RMSEA = Root-Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR = Standardised Root-Mean Squared Residual; IPV = Intimate partner violence. The Δχ2 represents the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-squared difference, as is recommended for comparisons of models using the maximum likelihood robust estimator. The Δχ2 and Δdf values presented in-line with Model 2 represent the comparison between Model 1 and Model 2; the Δχ2 and Δdf values in-line with Model 3 represent the comparison between Model 2 and Model 3.

p < .05.

p < .01.

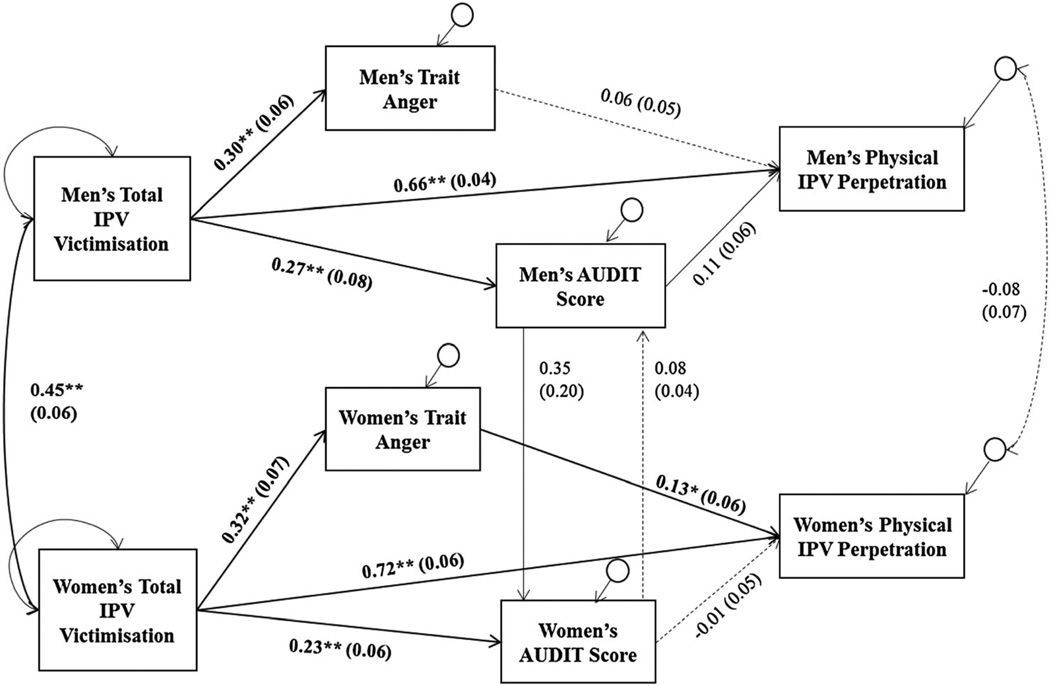

In Model 2, the direct effects of problematic alcohol use on partner perpetration were replaced with a direct feedback loop between men’s and women’s alcohol use. Results showed a significant improvement in fit relative to Model 1 (see Table 3). All paths and covariances remained significant from the previous model, with the exception that the path between men’s problematic alcohol use and IPV perpetration was no longer significant (p < .06). The direct path from men’s problematic alcohol use to women’s problematic alcohol use approached significance as well (p < .07). The reciprocal path from women’s problematic alcohol use to men’s problematic alcohol use failed to reach significance.

Model 3 removed all actor-partner effects to examine anger, problematic alcohol use and IPV variables simultaneously, but separately for men and women. Results indicated significantly poorer model fit relative to Models 1 and 2; thus, Model 2 had the superior relative fit to the data (Figure 2). In Model 2, the direct path between IPV victimisation and perpetration was stronger for women relative to men. Men showed a slightly stronger relationship between IPV victimisation and problematic alcohol use relative to women. The indirect effect of IPV victimisation on IPV perpetration via trait anger approached significance for women, β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p < .10. Similarly, the comparable indirect effect via problematic alcohol use approached significance for men, β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p < .10. Men’s and women’s IPV victimisation was observed to significantly covary across sex. However, the residuals for men’s and women’s physical IPV perpetration were not correlated.

Figure 2.

Indirect effect of IPV victimisation on IPV perpetration through anger for women; IPV victimisation on IPV perpetration through alcohol use for men, with unidirectional man-to-woman alcohol use partner effect. The path values represent the standardised beta coefficients with standard error presented in parentheses. Bold lines represent significant pathways, solid lines represent marginally significant pathways and dashed lines represent non-significant pathways. *p < .05; **p < .01. Intimate partner violence (IPV).

Discussion

We hypothesised that anger and problematic alcohol use would mediate the relation between IPV victimisation and perpetration for men and for women. Results supported prior research indicating IPV victimisation as one of the strongest predictors of perpetration for men and women (e.g. Stith et al., 2004; Slotter et al., 2012). Of the risk factors analysed, IPV victimisation showed the strongest unique relationship with perpetration for men and women. This direct effect was observed despite the indirect effects through anger for women and problematic alcohol use for men. Therefore, as prescribed by the I3 meta-theoretical model for IPV (Finkel and Eckhardt, 2013), our data support instigation as a necessary determinant of one’s likelihood for perpetrating IPV.

Results support the prediction that dispositional anger functions as an aggression-impelling influence that amplifies the urge toward aggressive behaviour provided by an instigating situation. For women, but not men, the indirect effect of trait anger on the victimisation-perpetration relation approached significance and may help to explain the moderate relationship between anger and aggression (e.g. Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015). Moreover, this finding indicates that anger may be a stronger impelling factor for women’s IPV perpetration than men in mutually violent relationships, as suggested by a recent daily diary study (Crane and Testa, 2014). However, the non-significant path from men’s anger to physical aggression was unexpected, as prior reviews have indicated a moderate effect of anger on IPV perpetration (e.g. Stith et al., 2004; Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015). It is important to note that trait anger was significantly correlated with total IPV victimisation (r = .30, p < .01) and physical IPV perpetration (r = .27, p < .01) for men. However, the indirect pathway from IPV victimisation to physical IPV perpetration was non-significant when problematic drinking and partner factors were examined within the same analyses. One explanation for why women’s perpetration appears to be more susceptible to anger’s impelling influence is provided in light of a recent investigation of ‘thresholds’ for physical IPV by perpetrator sex (i.e. Salis et al., 2014), which indicate that women may require a greater aggressive impulse than men in order to be physically aggressive. Thus, the present results suggest that other situational factors which more effectively ‘lower the bar’ for aggression through disinhibition (e.g. alcohol intoxication) might better account for men’s physical IPV compared to women. These results suggest, albeit cautiously, that clinicians may be wise to consider perpetrator sex when developing anger-focused interventions for IPV offenders.

Conversely, the indirect effect of IPV victimisation on IPV perpetration via problematic alcohol use approached significance for men only. This finding is consistent with prior studies which indicate that problematic alcohol use predicts men’s IPV perpetration (e.g. Testa et al., 2003). Interventions that integrate IPV and substance abuse content have shown reductions in IPV recidivism at follow-up for men with a history of IPV perpetration (Easton et al., 2007; Kraanen et al., 2013). While this work tends to exclude female perpetrators from their samples, the present results speculatively suggest that such programmes may be more applicable to male perpetrators.

Limitations and conclusions

The current study’s cross-sectional design lacks the temporal fidelity necessary to draw causal conclusions about the theorised indirect effects of the IPV victimisation–perpetration relationship. Thus, results offer only speculative inferences about specific dyadic processes involving alcohol use, anger and IPV. Additionally, this design prevents assessment of an event-based association between IPV and alcohol use. Further, anger and problematic drinking were assessed using single measures. Notably, participants who reported perpetration of severe physical IPV were excluded during telephone screening. Although 23% of the sample self-reported perpetration of at least one act of severe physical IPV in the past year when assessed in the laboratory, this exclusion criterion may still have influenced the generalisability of our results.

In conclusion, anger and problematic alcohol use may play important, but diverse, roles for men and women in couples at high-risk for IPV. This suggests the importance of assessment for these risk factors in both members of mutually violent couples, as the dynamics of the dyad influence the risk associated for each individual. The field places great importance on the identification of static risk factors for partner violence perpetration, but it is often forgotten that being a target of another person’s aggression is an important predictor of whether an individual will behave aggressively. These findings support the need for more process-focused, dyadically oriented conceptualisations of IPV in which relevant instigatory, impellance and inhibitory factors are considered simultaneously for men and women IPV perpetrators in mutually violent romantic relationships.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was facilitated, in part, by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant RO1AA020578 awarded to the second and third authors.

References

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 2002;7:313–351. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour KA, Eckhardt CI, Davison GC, Kassinove H. The experience and expression of anger in maritally violent and maritally discordant-nonviolent men. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Birkley E, Eckhardt CI. Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901013496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Eckhardt CI. Negative affect, alcohol consumption, and female-to-male intimate partner violence: a daily diary investigation. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:332–355. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.4.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M. Daily associations among anger experience and intimate partner aggression within aggressive and nonaggressive community couples. Emotion. 2014;14:985–994. doi: 10.1037/a0036884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M, Derrick JL, Leonard KE. Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: an examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior. 2014;40:440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais SL, Reeves KA, Nicholls TL, Telford RP, Fiebert MS. Prevalence of physical violence in intimate relationships, part 2: rates of male and female perpetration. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:170–198. [Google Scholar]

- Easton CJ, Mandel DL, Hunkele KA, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol-dependent domestic violence offenders: an integrated Substance Abuse–Domestic Violence treatment approach (SADV) The American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:24–31. doi: 10.1080/10550490601077809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI. Effects of alcohol intoxication on anger experience and expression among partner assaultive men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:61–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins SR, Moore TM, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Electronic diary assessment of the temporal association between proximal anger and intimate partner violence perpetration. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:100–113. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D. Cross-national research in self-reported crime and delinquency. Netherlands: Springer; 1989. Improving self-reported measures of delinquency; pp. 155–186. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11:193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, De Wall CN, Slotter EB, Oaten M, Foshee VA. Self-regulatory failure and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:483–499. doi: 10.1037/a0015433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Eckhardt CI. Intimate partner violence. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships. New York: Oxford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. MediaLab (Version 2006) New York, NY: Empirisoft; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kraanen FL, Vedela E, Scholing A, Emmelkamp PM. The comparative effectiveness of integrated treatment for Substance abuse and Partner violence (I-StoP) and substance abuse treatment alone: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Orengo-Aguayo R, Langer A, Brock RL. The impact and consequences of partner abuse on partners. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:406–428. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Krueger RF, Magdol L, Margolin G, Silva PA, Sydney R. Do partners agree about abuse in their relationship?: a psychometric evaluation of interpartner agreement. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:47. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 7.1.1) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salis KL, Kliem S, O’Leary KD. Conditional inference trees: a method for predicting intimate partner violence. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2014;40:430–441. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, Foran HM, Heyman RE, Snarr JD, Program UFAR. Identifying unique and shared risk factors for physical intimate partner violence and clinically-significant physical intimate partner violence. Aggressive Behavior. doi: 10.1002/ab.21565. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotter EB, Finkel EJ, De Wall CN, Pond RS, Jr, Lambert NM, Bodenhausen GV, Fincham FD. Putting the brakes on aggression toward a romantic partner: the inhibitory influence of relationship commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:291–305. doi: 10.1037/a0024915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimisation risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE. Substance abuse and relationship violence among men court-referred to batterers’ intervention programs. Substance Abuse. 2003;24:107–122. doi: 10.1080/08897070309511539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Does alcohol make a difference? Within-participants comparison of incidents of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(7):735–743. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]