Abstract

Background

A youth version of the UPPS Impulsivity Scale (UPPS-R-C) was previously shown to predict drinking initiation among pre-adolescents. The goals of the current study were to confirm the structure of the UPPS-R-C using a sample of treatment-seeking adolescents and to examine the scales’ relations with alcohol use, marijuana use, and problems related to substance use.

Method

Participants (N = 120; ages 12–18; M = 15.7) completed questionnaires at treatment intake. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the UPPS-R-C was conducted using a 5-factor model with factors corresponding to negative urgency, positive urgency, lack of perseverance, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Relations between UPPS-R-C factors and binge drinking, marijuana use, and problems resulting from substance use were examined using path analysis.

Results

CFA suggested the 5-factor model provided adequate fit to the data. The hypothesized path model was partially supported, positive urgency was associated with frequency of binge drinking, and both negative urgency and frequency of binge drinking was associated with problems due to substance use. Other hypothesized paths were not significant. Although not hypothesized, negative urgency was associated with frequency of marijuana use and lack of perseverance was associated with problems due to use.

Conclusions

Results suggest that the UPPS-R-C can be used with a treatment-seeking sample of adolescents. Furthermore, negative urgency, positive urgency, and lack of perseverance may be indicative of more severe substance use problems in a treatment setting.

Keywords: Urgency, Sensation Seeking, Adolescence, Binge Drinking, Marijuana Use

1. INTRODUCTION

Most individuals who become dependent on alcohol or illicit drugs initiate substance use during adolescence (Wagner and Anthony, 2002; Nixon and McClain, 2010). Thus, adolescence represents a critical time to provide early intervention for problematic substance use. Studies of non-clinical, community samples often find that older adolescents high in impulsivity are at greater risk for problematic substance use (e.g., Cooper et al., 2003; von Diemen et al., 2008). Preliminary evidence also suggests that impulsivity may negatively impact substance use treatment outcome for adolescents and young adults (Feldstein Ewing et al., 2009; Stanger et al., 2012; Bentzley et al., in press). Therefore, early intervention efforts targeting adolescents with heightened impulsivity may be particularly useful. Valid measurement of impulsivity among younger, treatment-seeking cohorts, such as pre-adolescent and adolescent clinical samples, is critical for early identification of individuals at-risk for severe substance use. The goals of the current study are to 1) validate a measure of impulsivity for use with adolescents seeking treatment for substance use disorders, and 2) examine associations between impulsivity and frequency of substance use and substance use severity among this population.

1.1. UPPS Model of Impulsivity

Impulsivity is a broad term encompassing a number of distinct, but related, constructs (e.g., Evenden, 1999; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001; Swann et al., 2002). With the goal of providing a unifying framework for impulsivity research, Whiteside and Lynam (2001) conducted a series of factor analyses on items designed to assess personality, impulsivity, sensation seeking, and emotion-based rash action. They found support for a four-factor model of impulsivity which they coined the “UPPS model.” The authors named the first factor “urgency,” which represents “a tendency to commit rash or regrettable actions as a result of intense negative affect” (p. 677). Second, they found support for a “lack of premeditation” factor. This represents lack of planning or careful, deliberate thinking prior to action. The third factor, named “lack of perseverance,” assessed one’s ability to persist with boring or difficult tasks. Fourth, a factor named “sensation seeking” represented excitement or thrill-seeking. Later, a fifth facet, “positive urgency”, defined as “the tendency to act rashly or maladaptively in response to positive mood states” (p.107), was added to create the UPPS-P (Cyders et al., 2007).

1.2. Measurement of Adolescent Impulsivity

Original psychometric validation of the UPPS and UPPS-P was conducted on samples of college students, consisting primarily of “emerging adults” (Arnett, 2000). This age group represents a developmental transition between adolescence and adulthood. The UPPS and UPPS-P measures have been administered to diverse adolescent samples (e.g., Delgado-Rico et al., 2012; Glenn and Klonsky, 2013; Stautz and Cooper, 2014), however.

Zapolski and colleagues (2010) created a modified youth version of the UPPS (UPPS-R-C) which contained fewer items per subscale. Items were reworded in order to eliminate any three syllable words and to make item content age-appropriate. The resulting measure was assessed to be at a 3.6-grade reading level. Zapolski and colleagues (2010) showed that the facets of the UPPS-R-C were internally consistent based on their administration of the measure to a sample of children from ages 7 to 13 (M=10.5); and, Gunn and Smith (2010) replicated the factor structure of the UPPS-R-C (with the addition of positive urgency) in a sample of non-clinical 5th graders (CFI=.93; RMSEA=.06, 90% CI: .05 to .06). Because the median age of alcohol and drug use disorder onset is 13–14 years old (Swendsen et al., 2012), it is important to ensure that measures are comprehensible to younger adolescents, while still being relevant for older adolescents. The UPPS-R-C provides an alternative for younger adolescents. However, to our knowledge, the factor structure of the UPPS-R-C has not been examined in a treatment-seeking sample of adolescents or among a wider youth age range.

1.3 Impulsivity and Substance Use Among Adolescents

There is evidence to suggest that heightened impulsivity is associated with alcohol use and problems resulting from use of alcohol (Stautz and Cooper, 2013) and, to a lesser extent, use of marijuana (Lynskey et al., 1998; Zapolski et al., 2009; Stautz and Cooper, 2014) among adolescents. In order to best identify adolescents most at-risk for substance use problems, it is important to determine which aspects of impulsivity are most associated with problematic substance use.

Stautz and Cooper (2013) conducted a meta-analysis of 87 studies examining adolescent alcohol use. They found that sensation seeking and positive urgency were most related to alcohol consumption in adolescence and that positive and negative urgency were most related to problems related to alcohol use among older adolescents. Though fewer studies examined relations between impulsivity and binge drinking, initial evidence suggests that sensation seeking and lack of premeditation are associated with increased frequency of binge drinking. Stautz and Cooper (2013) speculated that individuals high in sensation seeking and positive urgency may be motivated by the positively reinforcing effects of alcohol, leading to higher levels of consumption. Of note, a meta-analysis examining mostly young adult samples found that lack of perseverance was associated with frequency of binge drinking (Coskunpinar et al., 2013).

Stautz and Cooper’s (2013) meta-analysis included studies with an average sample age between 10 and 19.9; however, half of these studies were over college students and/or had an average age over 18 (n=43). Approximately 8% (n=7) of the included studies examined a clinical sample, and of those, only one study by Gabel and colleagues (1999) examined adolescents (Mean age=15.8) in residential substance use treatment specifically. They examined correlations between novelty seeking, a construct similar to sensation seeking, and alcohol (r=.18) and illicit drug dependence (r=.22) and found small associations. Other aspects of impulsivity were not examined. Given the paucity of research with this population, it is unclear whether Stautz and Cooper’s meta-analytic findings generalize to a younger, clinical population.

The relationship between impulsivity and marijuana use is mixed, as some researchers have found a relationship between frequency of marijuana use and impulsivity, particularly sensation seeking and positive urgency (Zapolski et al., 2009), and others have not (Field et al., 2006). Initial evidence suggests that positive and negative urgency are related to problems resulting from marijuana use (Stautz and Cooper, 2014). However, there is evidence to suggest that motivations to use marijuana are similar to motivations to use alcohol (Simons et al., 2000); thus, we may expect the same subgroups of adolescents who are at-risk for problematic alcohol use to be at-risk for problematic marijuana use. This is consistent with a model suggesting a common liability across substance use disorders (Lynskey et al., 1998; Tarter et al., 2003; Vanyukov et al., 2009).

1.4 Current Study

The first goal of the current study is to replicate the 5-factor structure of the UPPS-R-C in an adolescent population seeking treatment for substance use. The second goal of this study is to determine relations between facets of impulsivity and frequency of alcohol and marijuana use. In addition, relations between UPPS-R-C facets and problems resulting from substance use were examined. Based on previous findings, it was hypothesized that sensation seeking and positive urgency would be significantly positively related to frequency of marijuana use and that sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance would be significantly positively related to frequency of binge drinking. Given the well-established link between positive urgency and both frequency of alcohol use and problems related to alcohol use, it was theorized that positive urgency would also be related to frequency of binge drinking. Finally, it was hypothesized that negative urgency and positive urgency would be positively related to severity of problems resulting from substance use above and beyond frequency of use (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Stautz and Cooper, 2013; Stautz and Cooper, 2014).

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

Participants were adolescents, ages 12 to 18, who presented to an outpatient substance use clinic for treatment (see Magid and Settles, 2013 for details). At treatment intake, patients completed a series of questionnaires regarding substance use and impulsivity (described in Section 2.2). Of 139 adolescents who were assessed for treatment and administered all relevant measures, 120 provided valid UPPS-R-C data (i.e., correctly completed the measure and had variation in responses)1. Demographics and substance use frequencies for the sample are provided in Table 1. The mean age was 15.7 years (SD=1.3) in the overall sample. In the current sample, 37.6% of adolescents reported consuming alcohol and 25.4% reported consuming 5 or more drinks (4 or more for females) on one occasion at least monthly in the two months prior to the assessment. Additionally, 15.4% reported drinking (11.4% binge drinking) on a weekly basis, and less than 4% reported drinking or binge drinking 5 or more times per week. Marijuana use 47.1% reporting weekly use, and 22.7% reporting use 5 or more times per week.

Table 1.

Demographics and Substance Use Characteristics of Current Sample (N=120)

| Demographics and Substance Use | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 77 (64.2) |

| Race (n=119) | |

| White | 85 (71.4) |

| Black | 14 (11.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 8 (6.7) |

| Other | 12 (10.1) |

| Legally Mandated to Substance Use Treatment | |

| Yes | 14 (11.7) |

| No | 87 (72.5) |

| Unknown | 19 (15.8) |

| Past 2 Month Substance Use | |

| Alcohol Use (n=117) | 72 (61.5) |

| Binge Drinking (n=114) | 40 (35.1) |

| Marijuana Use (n=119) | 91 (76.5) |

| Alcohol Use + Marijuana Use (n=116) | 59 (50.9) |

| Binge Drinking + Marijuana Use (n=113) | 32 (28.3) |

| Cocaine Use (n=116) | 11 (9.5) |

| Amphetamine Use ( n=116) | 14 (12.1) |

| Opiate Use- Excluding Heroin (n=115) | 25 (21.7) |

| Heroin Use (n=115) | 5 (4.3) |

| Hallucinogen Use (n=116) | 18 (15.5) |

| Inhalant Use (n=117) | 8 (6.8) |

| Dextromethorphan Use (n=115) | 13 (11.3) |

2.2 Procedures and Measures

Participants were asked to complete a packet of questionnaires upon arrival for a scheduled intake session. The questionnaires were completed prior to the clinical assessment.

2.2.1 Frequency of Substance Use

As referenced in Section 2.1, participants were asked to report their frequency of marijuana and alcohol use in the past two months. Responses were provided on a scale with nine response options: never, 1–2 days in the past 2 months, 1 day a month, 2–3 days a month, 1 day a week, 2 days a week, 3–4 days a week, 5–6 days a week, or every day. In addition, participants reported the number of occasions in which they consumed 5 or more alcoholic drinks (4 or more drinks for females) within any two-hour period. A variable with a possible range of 0 to 8 was created for each frequency variable and was treated as a continuous variable for analysis. Of note, frequency of alcohol use and frequency of binge drinking were highly correlated in the current sample (r=0.67), and thus, only frequency of binge drinking was used in the current analyses, as this may be more clinically relevant for treatment-seeking adolescents.

2.2.2 The UPPS-R-Child Version (UPPS-R-C; Zapolski et al., 2010, Gunn and Smith, 2010)

The UPPS-R-C is a modified version of Whiteside and Lynam (2001)’s measure of impulsivity for adults. Zapolski and colleagues (2010) modified the item content to a 3rd to 4th grade reading level. The Child Version is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that assesses five factors of impulsivity: positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking. Each factor is assessed with 8 items. The item response scale is a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree. Zapolski and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that each of the four facets (excluding positive urgency) in their sample were highly internally consistent; sensation seeking had the highest internal consistency (α=.90) and lack of perseverance was the least internally consistent (α=.81). Internal consistency for each subscale ranged from .79 (lack of premeditation) to .95 (positive urgency) in the current sample.

2.2.3 Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989)

The RAPI is a 23-item measure designed to assess negative consequences related to alcohol use. For the purposes of our study, this measure was adapted to include problems related to alcohol and other drug use (see Ginzler et al., 2007). Participants are asked to report the frequency of problems in the past 2 months. An example item includes, “Got into fights, acted bad or did mean things.” Participants are asked to respond on a 5-point scale, with options including never, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, or more than 10 times. The RAPI has shown good internal consistency (White and Labouvie, 1989). Internal consistency of this measure was high in the current sample (α = .94).

2.3 Data Analysis

Thirty of the 120 participants included in the present analyses had a minimal number of missing item responses on the UPPS-R-C (n=20) and RAPI (n=15)2. These missing item responses were imputed by replacing the missing value with the mean of the sub-scale items for the UPPS-R-C and with the mean of the overall scale for the RAPI. The maximum number of items imputed per person was 5 items for the UPPS-R-C (M= .25, SD= .69) and 3 items for the RAPI (M=.17, SD=.50). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted Estimation (WLSMV) in Mplus Version 6.11 (Muthén and Muthén, 2011). The proposed model was a 5-factor model in which factors corresponded to negative urgency (8 items), positive urgency (8 items), lack of perseverance (8 items), lack of premeditation (8 items), and sensation seeking (8 items). Fit statistics are reported for the final model.

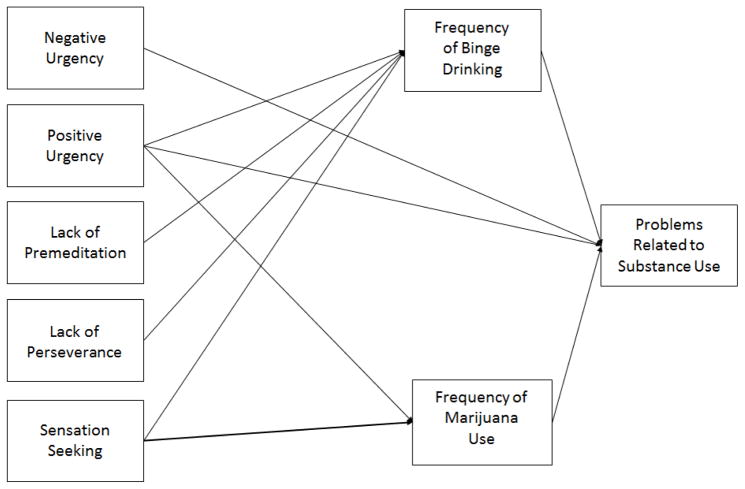

Associations between UPPS-R-C subscales and frequency of marijuana use, frequency of binge drinking (defined as five or more drinks in a 2 hour period for males; 4 or more drinks for females), and problems resulting from any substance use (RAPI, modified to include all substances) were examined using path analysis in MPlus Version 6.11. Specifically, the path model pictured in Figure 1 was estimated. In addition to the direct paths depicted in Figure 1, we estimated hypothesized indirect paths between positive urgency, premeditation, perseverance, and sensation seeking (independent variables) and substance-related problems (dependent variable) via binge drinking (mediator), as well as between positive urgency and sensation seeking (independent variables) and substance-related problems (dependent variables) via marijuana use (mediator). Of the sample of 120 individuals with valid UPPS-R-C data, 9 individuals were missing data on the frequency of binge drinking or marijuana use (i.e., 7 missing data points) or RAPI (i.e., 2 missing data points) variables. The model was estimated with maximum likelihood, which used all available data and yielded unbiased parameters under the assumption that missing data were missing at random. The significance of indirect paths was tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping procedures with 5,000 bootstrapped samples (MacKinnon, 2008). If overall model fit was not adequate for the hypothesized model (Kline, 2005), modification indices > 4 were examined for potential model modifications.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Path Model.

Note. Negative Urgency, Positive Urgency, Lack of Premeditation, Lack of Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking measured by the UPPS-R-C. Problems Related to Substance Use measured by the RAPI.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The results of the CFA suggested that the proposed 5-factor model provided adequate fit to the data (RMSEA=.08; 95% CI= .08–.09; CFI=.89; TLI=.89). One item proposed to load on the lack of premeditation factor, Item 4, appeared to be significantly related to all factors, based on modification indices. Additionally, several other items had poor factor loadings (less than .35), including one item proposed to load on the sensation seeking factor (Item 21) and two items on the lack of perseverance factor (Items 5 and 9).3

Items from the lack of premeditation subscale were constrained to load on Factor 1. Standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.55 (Item 25) to 0.80 (Item 6), suggesting good to excellent factor loadings (Comrey and Lee, 1992). Factor 2 consisted of items from the negative urgency subscale and standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.62 (Item 11) to 0.91 (Item 17), suggesting good to excellent factor loadings. Factor 3 consisted of items from the sensation seeking subscale and standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.33 (Item 21) to 0.87 (Item 18). Item loadings above 0.45 are considered fair (Comrey and Lee, 1992); thus, Item 21 is below this cut-off. However, all other factor loadings on this scale were fair to excellent (greater than or equal to β=.50). Factor 4 consisted of items from the lack of perseverance subscale. Two item loadings were below 0.45 (Item 5, β= 0.25; Item 9, β=0.24) and all other factor loadings were considered very good to excellent. The range for remaining items was 0.68 (Item 13) to 0.88 (Item 15). Factor 5 consisted of items from the positive urgency subscale and item loadings on this subscale were considered excellent, ranging from 0.79 (Item 33) to 0.96 (Item 37). A complete list of item factor loadings is provided in Table 2 and inter-factor correlations are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Standardized Factor Loadings and Standard Errors

| Items | Item Factor Loadings (SE) Full Scale |

|---|---|

| Factor 1- Lack of Premeditation | |

|

| |

| 4. I tend to blurt out things without thinking. | 0.61 (0.08) |

| 6. I like to stop and think about something before I do it. | 0.80 (0.05) |

| 10. I like to know just what to do before I start a project | 0.59 (0.07) |

| 16. I try to take a careful approach to things. | 0.68 (0.05) |

| 23. I am very careful. | 0.58 (0.07) |

| 25. I like to know what to expect, before doing something new. | 0.55 (0.07) |

| 28. I tend to stop and think before doing things. | 0.78 (0.04) |

| 29. Before making a choice, I tend to think about both the good things and the bad things about the choice. | 0.75 (0.05) |

|

| |

| Factor 2- Negative Urgency | |

|

| |

| 1. If I feel like doing something, I tend to do it, even if it’s bad. | 0.76 (0.06) |

| 7. When I feel bad, I often do things I later regret in order to make myself feel better now. | 0.75 (0.05) |

| 11. Sometimes when I feel bad, I keep doing something even though it is making me feel worse. | 0.62 (0.07) |

| 17. When I am upset I often act without thinking. | 0.91 (0.03) |

| 20. When I feel rejected, I often say things that I later regret. | 0.74 (0.05) |

| 26. I often make matters worse because I act without thinking when I am upset. | 0.90 (0.03) |

| 30. When I am mad, I sometimes say things that I later regret. | 0.67 (0.06) |

| 32. Sometimes I do crazy things I later regret. | 0.72 (0.05) |

|

| |

| Factor 3- Sensation Seeking | |

|

| |

| 2. I like new, thrilling things to happen. | 0.77 (0.06) |

| 8. I would like water skiing. | 0.50 (0.08) |

| 12. I enjoy taking risks. | 0.83 (0.06) |

| 14. I would like parachute jumping. | 0.64 (0.08) |

| 18. I like new, thrilling things, even if they are a little scary. | 0.87 (0.04) |

| 21. I would like to learn to fly an airplane. | 0.33 (0.10) |

| 27. I would like to ski very fast down a high mountain slope. | 0.68 (0.08) |

| 31. I would enjoy fast driving. | 0.81 (0.06) |

|

| |

| Factor 4- Lack of Perseverance | |

|

| |

| 3. I like to see things through to the end. | 0.71 (0.06) |

| 5. I am upset when I am not finished with things. | 0.25 (0.09) |

| 9. Once I get going on something I hate to stop. | 0.24 (0.08) |

| 13. It is easy for me to think hard. | 0.68 (0.06) |

| 15. I finish what I start. | 0.88 (0.03) |

| 19. I tend to get things done on time. | 0.74 (0.05) |

| 22. I am a person who always gets the job done. | 0.84 (0.04) |

| 24. I almost always finish projects that I start. | 0.77 (0.05) |

|

| |

| Factor 5- Positive Urgency | |

|

| |

| 33. When I am very happy, I can’t stop myself from going overboard. | 0.79 (0.04) |

| 34. When I am really thrilled, I tend not to think about the results of my actions. | 0.89 (0.03) |

| 35. When I am in a great mood, I tend to do things that could cause me problems. | 0.93 (0.02) |

| 36. I tend to act without thinking when I am very, very happy. | 0.87 (0.03) |

| 37. When I get really happy about something, I tend to do things that can lead to trouble. | 0.96 (0.01) |

| 38. When I am really happy, I tend to get out of control. | 0.87 (0.03) |

| 39. I tend to lose control when I am in a great mood. | 0.92 (0.02) |

| 40. When I am very happy, I tend to do things that may cause problems in my life. | 0.87 (0.03) |

Note. Estimates are item loadings for full UPPS scale (40 items) based on sample of 120 adolescents.

Table 3.

Inter-factor Correlations

| Negative Urgency | Sensation Seeking | Lack of Perseverance | Positive Urgency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Lack of Premeditation (F1) | .40* | .15 | .61* | .32* |

| Negative Urgency (F2) | -- | .30* | .03 | .59* |

| Sensation Seeking (F3) | -- | −.18 | .29* | |

| Lack of Perseverance (F4) | -- | .19 | ||

| Positive Urgency (F5) | -- | |||

Note. Estimates based on sample of 120 adolescents.

p<0.01

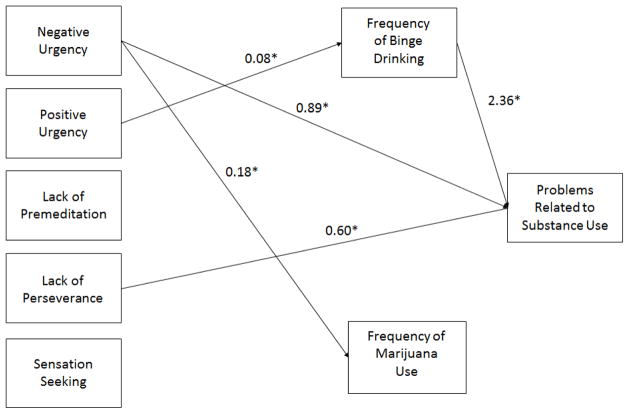

3.2 Substance Use Outcomes

The hypothesized path model (Figure 1) did not fit the data well (χ2 (8) = 19.08, p = 0.01, CFI = 0.86, TLI = 0.68, RMSEA = 0.11). Modification indices > 4 were examined for potential model modifications. First, a direct path between negative urgency and marijuana use was added (MI = 9.80). Second, a direct path between lack of perseverance and RAPI was added (MI = 5.22). Following these additions to the model, fit improved substantially (χ2 (6) = 3.62, p = 0.73, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00). As detailed in Table 4, paths from positive urgency to binge drinking (β = 0.08, p = 0.01), negative urgency to marijuana use (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), binge drinking to RAPI (β = 2.36, p = 0.04), negative urgency to RAPI (β = 0.89, p < 0.01), and lack of perseverance to RAPI (β = 0.60, p = 0.03) were statistically significant. Additionally, the indirect path from positive urgency to RAPI via binge drinking was significant (β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.04, 0.51]. No other direct or indirect effects were statistically significant. Significant paths are shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients from the Final Path Model Relating Personality (UPPS-R-C), Substance Use, and Substance-related Problems (RAPI)

| Binge Drinking | Marijuana Use | RAPI | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Direct Effects (p) | |||

| Negative Urgency (NU) | 0.18 (< 0.01) | 0.89 (< 0.01) | |

| Positive Urgency (PU) | 0.08 (0.01) | −0.05 (0.39) | 0.36 (0.14) |

| Lack of Premeditation (PM) | 0.07 (0.26) | ||

| Lack of Perseverance (PV) | −0.05 (0.42) | 0.60 (0.03) | |

| Sensation Seeking (SS) | 0.03 (0.31) | −0.06 (0.19) | |

| Binge Drinking | 2.36 (0.04) | ||

| Marijuana Use | 0.59 (0.25) | ||

| Indirect Effects (95% CI) | |||

| PU → Binge Drinking | 0.20 (0.04, 0.51) | ||

| PU → Marijuana Use | −0.03 (−0.19, 0.03) | ||

| PM → Binge Drinking | 0.16 (−0.07, 0.72) | ||

| SS → Binge Drinking | 0.07 (−0.05, 0.29) | ||

| SS → Marijuana Use | −0.04 (−0.19, 0.02) | ||

Note. Parameters from all estimated paths are provided. Significant effects (p < 0.05) are bolded. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index.

Figure 2.

Final Path Model with Significant Paths

Note. Regression weights are unstandardized. Negative Urgency, Positive Urgency, Lack of Premeditation, Lack of Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking measured by the UPPS-R-C. Problems Related to Substance Use measured by the RAPI.

4. DISCUSSION

The first goal of this study was to replicate the factor structure of the child version of a widely used measure of impulsivity, the UPPS-R-C, using an adolescent sample seeking outpatient treatment for substance use problems. The proposed 5-factor structure was reasonably supported and the internal consistencies of the subscales ranged from “good” to “excellent”. In sum, it appears that the UPPS-R-C is well-suited for assessing disinhibited personality among substance using clinical adolescent samples.

The second goal of this study was to examine associations between facets of impulsivity and substance use outcomes in this adolescent treatment-seeking sample. Positive urgency was associated with frequency of binge drinking, as predicted, such that high levels of positive urgency were associated with more frequent binge drinking. The other facets of impulsivity were not associated with binge drinking. When in a good mood, adolescents high in positive urgency may be more likely to socialize or party with alcohol (as opposed to marijuana), which is consistent with evidence suggesting that experienced users are more likely to endorse social motives for alcohol use, rather than marijuana use (Simons et al., 2000). It is possible that these adolescents are not planning to binge drink in a premeditated manner, but rather that they have difficulty moderating alcohol consumption when experiencing positive mood states. Binge drinking increases the likelihood of negative alcohol-related consequences, as even one episode of binge drinking can have serious consequences. Adolescents high in positive urgency may benefit from interventions and prevention efforts that aim to reduce binge drinking in social/celebratory settings, such as promoting awareness of alcohol-free activities.

Contrary to hypothesis, sensation seeking and positive urgency were not related to frequency of marijuana use. Rather, negative urgency significantly associated with frequency of marijuana use. Consistent with findings from Stautz and Cooper (2014), high levels of negative urgency were related to more frequent marijuana use. The adolescents high in negative urgency may be particularly motivated to use marijuana to cope with negative emotional states (Cooper et al., 1995; Simons et al., 1998; Adams, Kaiser, Lynam et al., 2012). Thus, interventions designed to increase emotion regulation skills may be highly relevant for individuals presenting to treatment for marijuana cessation.

Finally, it was predicted that positive and negative urgency would be related to substance-related problems, in addition to direct paths from frequency of binge drinking and frequency of marijuana use. Negative urgency was significantly positively related to problematic use which is consistent with findings from previous studies (e.g., Stautz and Cooper, 2014; Wray et al., 2012). Positive urgency was indirectly associated with problematic use, as frequency of binge drinking mediated the relationship between positive urgency and problematic use. This indirect association is consistent with alcohol findings from a college sample (Wray et al., 2012), but inconsistent with alcohol and marijuana findings in a normative adolescent sample (Stautz and Cooper, 2014). Of note, the adolescent sample in the Stautz and Cooper (2014) study used substances less frequently than the current, treatment-seeking sample and the college-student sample in Wray et al. (2012). Perhaps among more frequent substance users, positive urgency exerts only an indirect effect on substance use problems.

Though not hypothesized, lack of perseverance was also significantly positively related to problematic use. Although speculative, it may be that adolescents who lack perseverance are less likely to be goal-oriented or persevere with tasks consistent with academic and athletic goals. This type of goal striving may be protective against problematic substance use, as adolescents with high aspirations may be less likely to engage in behaviors that could cause social, legal, and academic problems for them, thus, interfering with other goals.

These findings should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the sample size is on the lower end of suggested ranges for confirmatory factor analysis (Fabrigar et al., 1999), so the factor structure should be replicated among independent samples. The smaller sample size also precluded examination of additional moderators, such as age, gender, and race, which is an important limitation to be addressed in future research. Second, some items had poor fit in the current study. These items may be less relevant for youth and teenagers today. For example, learning how to fly an airplane (Item 21) may not be something in which many of today’s youth express interest. Likewise, two items related to how one prioritizes and values task completion (Items 5 and 9) may be less relevant for younger samples generally in an adult’s care.

Third, one of the outcome measures, the RAPI was modified to include other drugs in addition to alcohol. While Ginzler and colleagues (2007) show that multiple drugs can be reliably assessed with a single administration of the RAPI, the measure has not been as extensively validated with this modification. Fourth, substance use behavior and problems due to use were measured via self-report. Thus, substance use may be under-reported for some individuals due to impression management, avoidance of perceived negative consequences, and limitations in retrospective recall (e.g., Nisbett and Wilson, 1977; Johnson and Fendrich, 2005). In addition, other use measures, such as the Timeline Follow-back (Sobell and Sobell, 1992), may have improved accuracy of reporting.

Fifth, the current sample was skewed toward heavier marijuana use than alcohol use. Thus, it is unclear how the results would generalize to a sample recruited for heavy drinking.

Finally, the current analyses were conducted on cross-sectional data. Therefore, it is not possible to make causal claims regarding the nature of the relationship between impulsivity and substance use in this sample.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study examining relations between UPPS impulsivity and substance use in an adolescent sample recruited from a clinical, outpatient substance use program. The UPPS-R-C may be an alternative to the UPPS/UPPS-P for clinicians and researchers interested in examining impulsivity in a broad adolescent age range. Additionally, the UPPS-R-C may be a useful assessment for clinicians to administer to treatment seeking adolescents in order to identify individuals at-risk for more severe substance use outcomes.

Future research should examine the extent that impulsivity “styles” are uniquely related to why or how an adolescent uses substances (e.g., Magid et al., 2007). Additionally, it will be important to examine how these impulsivity facets impact treatment outcome for substance-using adolescents. In the future, it may be possible to personalize adolescent substance use treatment based on personal characteristics, such as impulsivity-related traits.

Highlights.

Factor structure of youth UPPS-R-C is replicated with adolescent clinical sample.

Negative urgency/lack of perseverance related to problems due to substance use.

Positive and negative urgency show nuanced relations with frequency of substance use.

Binge drinking mediates relations between positive urgency and problems due to use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (T32 AA007474; K23 AA020842).

Role of Funding Source

The funding sources for this project had no involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, or submission.

Footnotes

Contributors

Viktoriya Magid was responsible for study design and implementation. Rachel Tomko and Viktoriya Magid formed research ideas. Rachel Tomko completed the review of the literature. Rachel Tomko and Sandhya Kutty Falls were responsible for data management. James Prisciandaro and Rachel Tomko analyzed the data and wrote the methods/results. Rachel Tomko wrote the introduction/discussion under Viktoriya Magid’s mentorship. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

A participant was excluded from analyses if the participant did not complete one or more full pages of the UPPS-R-C (n=9), endorsed the same response for all items or nearly all items on the UPPS-R-C (including reverse-coded items, indicating failure to fully read and/or truthfully respond to items; n=9), or if the participant endorsed multiple responses per item (n=1). was more prevalent in the current sample, with 58.0% of adolescents reporting monthly use,

Five participants had 1 or more items missing from both measures.

Dropping items 4, 5, 9, and 21 improved model fit (RMSEA=.07; 95% CI= .06-.08; CFI= .95; TLI=.94); however, all items were retained in subsequent analyses in order to preserve the original scale for purpose of replication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rachel L. Tomko, Email: tomko@musc.edu.

James J. Prisciandaro, Email: priscian@musc.edu.

Sandhya Kutty Falls, Email: fallss@musc.edu.

Viktoriya Magid, Email: magid@musc.edu.

References

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addict Behav. 2012;37:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley JP, Tomko RL, Gray KM. Impulsivity, craving, and medication non-adherence predict non-abstinence in a trial of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in adolescents with cannabis use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.12.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A First Course In Factor Analysis. 2. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, Albino A. Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:390–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Rico E, Río-Valle JS, González-Jiménez E, Campoy C, Verdejo-García A. BMI predicts emotion-driven impulsivity and cognitive inflexibility in adolescents with excess weight. Obesity. 2012;20:1604–1620. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/PL00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:272–299. 1082-989X/99/S3.00. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SWF, LaChance HA, Bryan A, Hutchinson KE. Do genetic and individual risk factors moderate the efficacy of motivational enhancement therapy? Drinking outcomes with an emerging adult sample. Addict Biol. 2009;14:356–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Eastwood B, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Selective processing of cannabis cues in regular cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel S, Stallings MC, Schmitz S, Young SE, Crowley TJ, Fulker DW. Personality dimensions and substance misuse: Relationships in adolescents, mothers and fathers. Am J Addict. 1999;8:101–113. doi: 10.1080/105504999305901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzler JA, Garrett SB, Baer JS, Peterson PL. Measurement of negative consequences of substance use in street youth: an expanded use of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1519–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Reliability and validity of borderline personality disorder in hospitalized adolescents. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:206–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RL, Smith GT. Risk factors for elementary school drinking: pubertal status, personality, and alcohol expectancies concurrently predict fifth grade alcohol consumption. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:617–627. doi: 10.1037/a0020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T, Fendrich M. Modeling sources of self-report bias in a survey of drug use epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles And Practice Of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. Guilford; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The origins of the correlations between tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use during adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 1998;39:995–1005. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction To Statistical Mediation Analysis. Erlbaum; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Maclean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Settles R. Clinical guidelines for the detection, prevention, and early intervention of adolescent substance use. Adolesc Psychiatr. 2013;3:200–207. doi: 10.2174/2210676611303020012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Wilson TD. Telling more than we can know: verbal reports on mental processes. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:231–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, McClain JA. Adolescence as a critical window for developing an alcohol use disorder: current findings in neuroscience. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2010;23:227–232. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833864fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addict Behav. 2000;25:153–160. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. J Couns Psychol. 1998;45:265–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; New York: 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Ryan SR, Fu H, Landes RD, Jones BA, Bickel WK, Budney AJ. Delay discounting predicts adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2012;20:205–212. doi: 10.1037/a0026543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Urgency traits and problematic substance use in adolescence: direct effects and moderation of perceived peer use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0034346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM. Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol Psychiatr. 2002;51:988–994. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, Conway KP, Dierker L, He J, Merikangas KR. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2012;69:390–398. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Gardner W, Blackson T, Clark D. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatr. 2003;160:1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Moss L, Tarter RE, Reynolds MD, Maher BS, Krilova GP, Ridenour T, Clark DB. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders: Phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behav Genet. 2009;39:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Diemen L, Bassani DG, Fuchs SC, Szobot CM, Pechansky F. Impulsivity, age of first alcohol use and substance use disorders among male adolescents: a population based case–control study. Addiction. 2008;103:1198–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence: developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;26:479–488. doi: 10.1038/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;30:669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Gaher RM. Trait-based affective processes in alcohol-involved “risk behaviors”. Addict Behav. 2012;37:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17:116–125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal druguse and risky sexual behavior. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]