Abstract

Introduction

The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation Screening Outcome Evaluation examined whether universal suicide risk screening is feasible and effective at improving suicide risk detection in the emergency department (ED).

Methods

A three-phase interrupted time series design was used: Treatment as Usual (Phase 1), Universal Screening (Phase 2), and Universal Screening + Intervention (Phase 3). Eight EDs from seven states participated from 2009 through 2014. Data collection spanned peak hours and 7 days of the week. Chart reviews established if screening for intentional self-harm ideation/behavior (screening) was documented in the medical record and whether the individual endorsed intentional self-harm ideation/behavior (detection). Patient interviews determined if the documented intentional self-harm was suicidal. In Phase 2, universal suicide risk screening was implemented during routine care. In Phase 3, improvements were made to increase screening rates and fidelity. Chi-square tests and generalized estimating equations were calculated. Data were analyzed in 2014.

Results

Across the three phases (N=236,791 ED visit records), documented screenings rose from 26% (Phase 1) to 84% (Phase 3) (χ2 [2, n=236,789]=71,000, p<0.001). Detection rose from 2.9% to 5.7% (χ2 [2, n=236,789]=902, p<0.001). The majority of detected intentional self-harm was confirmed as recent suicidal ideation or behavior by patient interview.

Conclusions

Universal suicide risk screening in the ED was feasible and led to a nearly twofold increase in risk detection. If these findings remain true when scaled, the public health impact could be tremendous, because identification of risk is the first and necessary step for preventing suicide.

Introduction

The suicide rate in the U.S. has risen almost 30% over the past 20 years.1 As discussed in a special issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine,2 healthcare settings play a crucial role in identifying individuals who are at risk for suicide. Emergency departments (EDs) may be particularly important for such efforts.3–9 Many ED patients have unrecognized risk incidental to their chief complaint.10–12 In the two largest studies to date, point prevalence of active ideation among ED patients presenting with non-psychiatric complaints was 8%,13,14 which went undetected by treating ED clinicians. This far exceeds community estimates of around 3% over a period of an entire year.15 Many individuals who are treated in an ED and then die by suicide do not present for a psychiatric problem and their risk is not detected during the visit.16,17

The ED Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE18,19) is a multicenter collaborative study with two overarching objectives:

to develop and test a standardized approach to universal suicide risk screening within the general medical ED (the Screening Outcome Evaluation); and

to test an ED-initiated intervention with follow-up telephone contact to reduce suicidal behavior among people who screen positive for suicide risk (the Intervention Evaluation).

The current paper reports key findings from the Screening Outcome Evaluation.

Methods

A detailed review of the study’s design and methods has been published.18 ED-SAFE used an interrupted time series design with three phases:

Treatment as Usual;

Universal Screening; and

Universal Screening + Intervention.

Eight participating sites were randomly assigned to one of four cohorts, and each cohort was randomly assigned to a start date and progressed through the three phases sequentially (random stepped wedge design).20 The Screening Outcome Evaluation used data from all three phases. The study was approved by the IRBs of all participating institutions. Because primary data were collected by chart review, the requirement for informed consent was waived. Patients who were approached for additional questioning provided verbal informed consent to be interviewed. All adult ED patients who were treated in one of the eight participating sites during any of the three study phases were eligible for chart review.

Setting

Eight hospitals located in seven states participated. Annual ED census ranged from 31,000 to 54,000. Like most U.S. EDs, participating sites did not have dedicated psychiatric EDs,21 to increase the representativeness of the findings.

At baseline, sites generally screened for suicide risk only among those who presented with frank psychiatric symptoms. One site had already implemented universal screening during Phase 1 using a single item screener created by the site. This implementation occurred after the site had been selected for participation (at the time of selection, it did not have universal screening) but before Phase 1 had started and was attributed to the hospital’s risk management concerns about complying with Joint Commission requirements.

Implementing Universal Screening

The investigative team and representatives from all eight sites used the best evidence available to create a screener feasible to implement in emergency settings. The Patient Safety Screener-3 (PSS-322) assesses depressed mood, active suicidal ideation in the past 2 weeks, and lifetime suicide attempt. If lifetime attempt is endorsed, the timing of the most recent attempt is identified. A positive screen was defined as active suicidal ideation in the past 2 weeks or a suicide attempt within the past 6 months. The depression item is not factored into screening results; it was included as segue to help “ease into” the suicide items, which can be jarring when asked without context. A positive screen on the PSS-3 has strong agreement (κ=0.95) with the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation,23 a well-established suicide risk instrument.22

Prior to Phase 2, each site convened a performance improvement team to develop strategies the site could use to improve implementation of universal screening. The team composition and performance improvement methods followed those commonly used by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,24 an industry leader. The team was multidisciplinary, including practicing clinicians to administrators, and focused on using continuous quality improvement cycles. The Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) strategy was used, which included planning the desired changes (Plan), implementing them (Do), measuring performance (Check), and making adjustments (Act). The PDCA process was repeated as often as needed. Each site’s team received centralized training on these methods and their relationship to suicide risk screening to assure a common knowledge base. Although the precise clinical protocols were not dictated, there were two requirements:

The site needed to use the PSS-3.

The PSS-3 was to be administered universally for all patients, with notation if the individual was inappropriate to screen because of his or her medical condition (e.g., unconscious, cognitively disabled).

Screening during triage for patients who presented with a psychiatric complaint was maintained. However, screening during triage for individuals with non-psychiatric complaints was strongly discouraged because of concerns about slowing ED flow. For most sites, the PSS-3 was administered during the primary nursing assessment once the patient was placed in a treatment area. Some sites chose to use the PSS-3 during triage for psychiatric patients as well. Each site’s performance improvement team created written clinical protocols, which stipulated how positive screens would be managed.

Nurses at each site were either trained by trainers recruited from the site’s clinical staff or through a webinar provided by the ED-SAFE trainer. Each site’s performance improvement team was responsible for collecting its own data on performance independent of the research data (e.g., screening rates), making adjustments to protocols as needed, and providing feedback, additional training, and other small incentives (e.g., $5 gift cards and lunches) to promote performance. An a priori “Excellence” screening rate of 75% was set by consensus.

During Phase 3, sites continued to improve screening using PDCA cycles. See Methods paper(pp 15–16) for additional information on the additional interventions introduced during Phase 3.

Data Collection

Across all phases, sites staffed the ED with research assistants (RAs) at least 40 hours/week during peak volume hours (12:00pm to 10:00pm), with at least 1 weekend day/month. As both volume and enrollment rates decline after 10:00PM, this efficiently maximized the representativeness of the sample. All adult patients who entered the ED during data collection shifts were documented on a Screening Log, and the RA reviewed their medical charts in real time throughout the visit until the patient was discharged. This was done both to obtain screening data (goal of the present study) and to identify subjects for the longitudinal clinical trial. Although the RAs were not blinded to phase, additional data sources were used to expand and validate outcomes abstracted by chart review, including patient interview and random chart review. Information on the fidelity interviews used to validate medical record documentation is reported in Appendix A. Data were collected from 2009 through 2014 and analyzed in 2014.

Outcome Definitions

The study was directed at improving suicide risk screening and detection. There were two primary outcomes. The first outcome, documentation of intentional self-harm ideation or behavior screening, was defined broadly as any documentation of past or current intentional selfharm ideation or behavior appearing in the record as either present or absent. The second outcome, intentional self-harm risk detection, was defined as past or current intentional self-harm ideation or behavior documented as positive in the ED medical record. A broad initial threshold comprising any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior was used because ED documentation may be vague or incomplete as to whether intentional self-harm is suicidal or not, particularly during treatment as usual, and could introduce error and unreliability across raters (Limitations section). Consequently, the protocol tracked documentation of any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior, not just suicidal self-harm ideation or behavior, and clarified the nature of the selfharm using a subsequent direct research interview with the patient. Passive ideation only, such as a desire to go to sleep and not wake up, was not considered a positive screen.

Measures

The Screening Log extracted data from the medical record. The RA recorded demographic information, whether any screening for intentional self-harm ideation or behavior was documented anywhere on the patient’s ED medical record, and whether self-harm ideation or behavior was documented as present (positive screen) or absent (negative screen). A positive screen was further classified by the RA using chart documentation only as current (i.e., self-harm ideation or behavior occurring during or immediately preceding the current ED visit), past (i.e., noted in the past but not currently), or unknown time (i.e., documented without a clear time reference).

In addition, through all three phases, an RA approached all individuals with documentation reflecting intentional self-harm ideation or behavior and directly interviewed the patient. Patients who were incarcerated or too medically, cognitively, or emotionally ill to be interviewed were excluded. Intentional self-harm ideation or behavior was further clarified as suicidal ideation or behavior within the past week, including the day of the visit (yes/no).

Because RAs did not staff the ED 24 hours/day, 7 days/week, a separate sample of 2,400 randomly selected charts was collected (100/site × 8 sites × 3 phases) as a validation sample. The RA recorded whether there was documentation in the chart of:

any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior screening;

any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior detection;

suicidal ideation (past or current); and

suicide attempts (past or current).

More information on these procedures is published.25

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using Stata, version 13.1. Data are presented as proportions with 95% CIs and medians with interquartile ranges. Changes in documentation of screening and detection were evaluated by analyzing data from the Screening Log using chi-square tests. Analyses were repeated using random chart review data as a confirmation of trends. To examine trends across the three study phases and control for potential clustering by site, generalized estimating equations with a logit link function were used. All p-values are two-tailed, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Time series figures displaying screening and detection rates were generated from Screening Log data.

Results

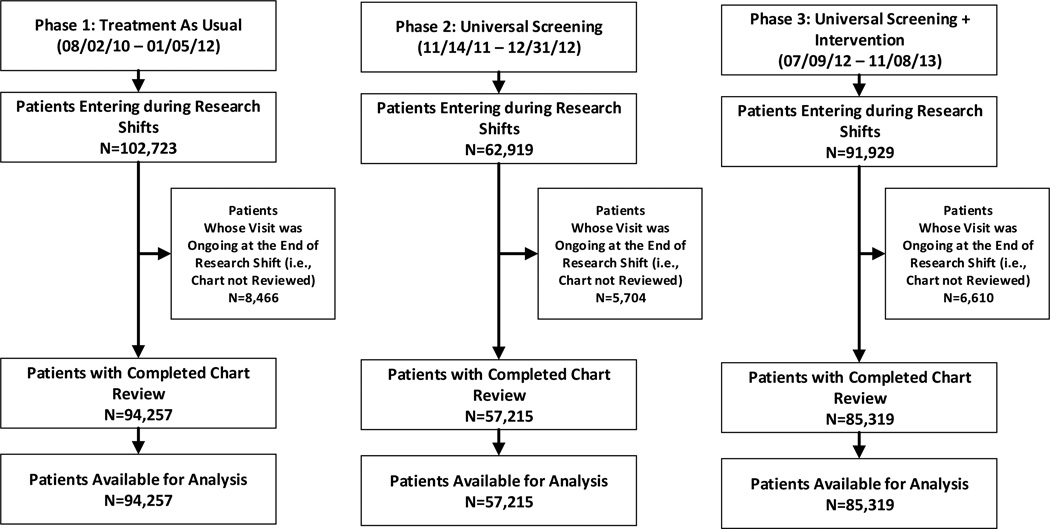

Across the three phases, RAs reviewed 236,791 ED visit records (Figure 1, Table 1), identified 10,625 patients with any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior, and completed 3,101 patient interviews. The demographics were compared to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey,26 which samples ED visits nationally. The ED-SAFE sample was very similar to the national sample.

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

Note: This was an interrupted time series trial that used data collected during an index emergency department visit; therefore, there was no follow-up or attrition.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Emergency Department Patients, Overall and by Study Phase

| Overall (n=236,791) |

Treatment as usual (Phase 1) (n=94,257) |

Universal screening (Phase 2) (n=57,215) |

Universal screening + intervention (Phase 3) (n=85,319) |

p- value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age, in years | |||||||||

| Age, mean | 45 | 45 | 46 | 46 | |||||

| (SD) | 236,744 | (19) | 94,246 | (19) | 57,194 | (19) | 85,304 | (19) | <0.001 |

| 18–24 | 32,017 | 13.5 | 13,192 | 14.0 | 7,614 | 13.3 | 11,211 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 46,728 | 19.7 | 18,861 | 20.0 | 11,310 | 19.8 | 16,557 | 19.4 | |

| 35–44 | 40,934 | 17.3 | 16,667 | 17.7 | 9,859 | 17.2 | 14,408 | 16.9 | |

| 45–54 | 45,118 | 19.1 | 18,124 | 19.2 | 10,737 | 18.8 | 16,257 | 19.1 | |

| 55–64 | 32,133 | 13.6 | 12,047 | 12.8 | 7,813 | 13.7 | 12,273 | 14.4 | |

| 65–74 | 17,930 | 7.6 | 6,859 | 7.3 | 4,466 | 7.8 | 6,605 | 7.7 | |

| >75 | 21,884 | 9.2 | 8,496 | 9.0 | 5,395 | 9.4 | 7,993 | 9.4 | |

| ND | 47 | 0.02 | 11 | 0.01 | 21 | 0.04 | 15 | 0.02 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Female | 129,078 | 54.5 | 51,435 | 54.6 | 31,583 | 55.2 | 46,060 | 54.0 | |

| ND | 59 | 0.02 | 22 | 0.02 | 19 | 0.03 | 18 | 0.02 | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 138,098 | 58.3 | 54,305 | 57.6 | 33,672 | 58.9 | 50,121 | 58.8 | |

| Black | 51,657 | 21.8 | 21,708 | 23.0 | 12,844 | 22.5 | 17,105 | 20.1 | |

| Other | 7,577 | 3.2 | 2,804 | 3.0 | 2,126 | 3.7 | 2,647 | 3.1 | |

| ND | 39,459 | 16.7 | 15,440 | 16.4 | 8,573 | 15.0 | 15,446 | 18.1 | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 36,264 | 15.3 | 14,535 | 15.4 | 8,727 | 15.3 | 13,002 | 15.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 91,387 | 38.6 | 29,697 | 31.5 | 21,166 | 37.0 | 40,524 | 47.5 | |

| ND | 109,140 | 46.1 | 50,025 | 53.1 | 27,322 | 47.8 | 31,793 | 37.3 | |

| Day of week | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Sunday | 7,934 | 3.4 | 2,842 | 3.0 | 1,871 | 3.3 | 3,221 | 3.8 | |

| Monday | 46,093 | 19.5 | 16,935 | 18.0 | 11,093 | 19.4 | 18,065 | 21.2 | |

| Wednesday | 46,910 | 19.8 | 19,019 | 20.2 | 11,218 | 19.6 | 16,673 | 19.5 | |

| Thursday | 44,327 | 18.7 | 17,916 | 19.0 | 11,674 | 20.4 | 14,737 | 17.3 | |

| Friday | 30,502 | 12.9 | 13,494 | 14.3 | 6,950 | 12.2 | 10,058 | 11.8 | |

| Saturday | 11,737 | 5.0 | 4,545 | 4.8 | 2,255 | 3.9 | 4,937 | 5.8 | |

| Site | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 1 | 42,027 | 17.8 | 15,950 | 16.9 | 8,079 | 14.1 | 17,998 | 21.1 | |

| 2 | 19,140 | 8.1 | 6,798 | 7.2 | 4,801 | 8.4 | 7,541 | 8.8 | |

| 3 | 31,378 | 13.3 | 9,934 | 10.5 | 8,873 | 15.5 | 12,571 | 14.7 | |

| 4 | 22,306 | 9.4 | 14,870 | 15.8 | 2,867 | 5.0 | 4,569 | 5.4 | |

| 5 | 39,872 | 16.8 | 15,174 | 16.1 | 11,065 | 19.3 | 13,633 | 16.0 | |

| 6 | 28,675 | 12.1 | 10,786 | 11.4 | 7,868 | 13.8 | 10,021 | 11.8 | |

| 7 | 28,120 | 11.9 | 12,679 | 13.5 | 8,507 | 14.9 | 6,934 | 8.1 | |

| 8 | 25,273 | 10.7 | 8,066 | 8.6 | 5,155 | 9.0 | 12,052 | 14.1 | |

ND, not documented

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

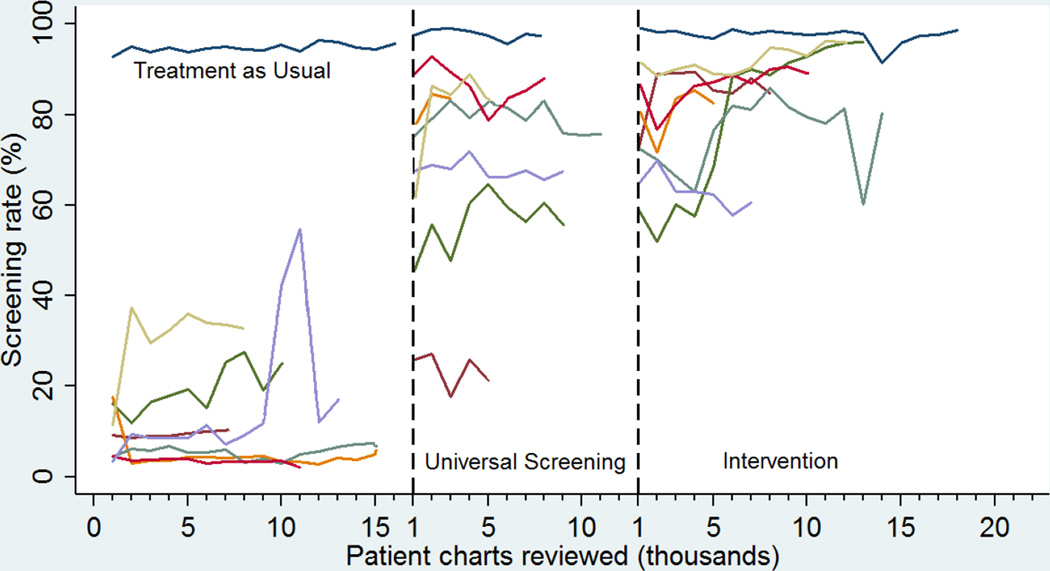

Documentation of screening for any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior improved from 26% in Phase 1 to 73% and 84% in Phases 2 and 3, respectively, χ2 [2, n=236,789]=71,000, p<0.001, p for trend adjusted for site clustering <0.001). Similar increases were noted using random chart review data (24%, 72%, and 84% in Phases 1, 2, and 3, respectively [χ2 (2, n=2,398)=679, p<0.001, p for trend adjusted for site clustering <0.001]). The rate of screening across phases for each site can be seen in Figure 2. The Phase 3 screening rates by site ranged from 63% to 98%, with seven sites reaching >75%.

Figure 2. Time series plot of screening rates by site across the three phases.

Lines represent the percentage of patients that were screened for intentional self-harm. One site (dark blue) achieved 95% screening in Treatment as Usual, because hospital administration interpreted the Joint Commission Patient Safety Goal 15 as requiring universal screening. This site implemented the screening after site selection had been completed for the study but before Treatment as Usual began. In Phase 2, this site switched over to the PSS-3 and continued universal screening.

Detection of any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior rose from 2.9% in Phase 1 to 5.2% and 5.7% in Phases 2 and 3, respectively (χ2 [2, n=236,789]=902, p<0.001), with the largest increase occurring between Phases 1 and 2 (p with adjustment for site clustering=0.008) (Table 2). Documentation of intentional self-harm ideation or behavior in the week prior to the visit rose from 2.7% to 3.9% (χ2 [2, n=236,789]=205, p<0.001), while past intentional self-harm ideation or behavior at any time other than the past week rose from 0.3% to 1.9% (χ2 [2, n=236,789]=1,200, p<0.001). Analyses with random chart review data revealed similar increases (2.8%, 5.8%, and 7.3% in Phases 1, 2, and 3, respectively, χ2 [2, n=2,398]=17, p<0.001). Appendix Figure B1 depicts the risk detection rates across all three phases over time. Multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for patient clustering by site and demographics did not materially affect the results (Appendix Table B1).

Table 2.

Screening Log and Random Chart Review Risk Detection Rates by Phase

| Treatment as Usual (Phase 1) |

Universal Screening (Phase 2) |

Universal Screening + Intervention (Phase 3) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI |

n | % | 95% CI |

n | % | 95% CI |

p for trend adjusted for clustering by site |

||||

| Screening Log (n=236,791) Documentation of… | |||||||||||||

| Any self-harma (positive) | 2,771 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2,953 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 4,901 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Current self-harm b (positive) | 2,516 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 1,863 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3,299 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Past self-harmc (positive) | 255 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1,090 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1,602 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Random Chart Review (n=2,400) Documentation of… | |||||||||||||

| Any self-harma (positive) | 22 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 46 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 58 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 9.3 | 0.009 |

| Any suicidal ideation (positive) | 18 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 27 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 22 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 0.62 |

| Current suicidal ideationd (positive) | 8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 15 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 16 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 0.28 |

| Past suicidal ideatione (positive) | 10 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 12 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.17 |

| Any suicide attempt (positive) | 14 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 32 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 46 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 0.02 |

| Current suicide attemptf (positive) | 2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.72 |

| Past suicide attemptg (positive) | 12 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 26 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 43 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 0.02 |

Any self-harm = Any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior noted on ED medical record

Current self-harm = any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior within the past 2 weeks, including day of visit

Past self-harm = any intentional self-harm ideation or behavior older than the past 2 weeks, or unknown/unspecified time

Current suicidal ideation = any thoughts about killing oneself within the past 2 weeks, including day of visit

Past suicidal ideation = any thoughts about killing oneself older than the past 2 weeks, or unknown/unspecified time

Current suicide attempt = any attempt to end one’s life within the past 2 weeks, including day of visit

Past suicide attempt = any attempt to end one’s life older than the past 2 weeks, or unknown/unspecified time

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Direct patient interview data (n=3,101) found that, across all three phases, approximately 74% (95% CI=73%, 76%) of patients with any intentional self-harm reported suicidal ideation or an attempt within the past week, supporting that the majority of the self-harm detection was relatively recent suicidal ideation or behavior.

Discussion

Although research has repeatedly suggested that ED patients have significant undetected suicide risk, this is the first study to address the key question of whether detection feasibly can be increased by implementing universal suicide risk screening protocols in the ED. Two main conclusions can be reached. First, increasing documented suicide risk screening rates in the general adult ED population during routine care was achieved using a simple screener and Institute for Healthcare Improvement performance improvement protocols. Second, increased screening led to nearly twice as many patients being identified as having suicide risk, either by virtue of endorsing active suicidal ideation or a past suicide attempt. If applied to the approximately 350,000 ED visits that occur annually at the eight participating EDs alone, nearly 10,000 additional patients with previously undetected suicide risk would be identified every year.

Documented screenings rose from an average of 26% in Phase 1 to an average of 84% in Phase 3, representing an increase of more than 300% (Figure 1). Moreover, this increase in screening led to a nearly twofold increase in identification of patients positive for suicide risk. Documentation of any past or current intentional self-harm ideation or behavior nearly doubled over the course of the study from 2.9% to 5.7%. Patient interviews confirmed that the majority of this intentional self-harm was suicidal ideation or behavior that occurred in the weeks before the ED visit. Findings using data obtained during active research shifts, which disproportionately captured hours from 9am to 10pm, were reinforced by findings from random chart reviews. Furthermore, the positive trends in screening and detection persisted even after adjusting for factors such as site, demographics, and fidelity (Appendix A).

Importantly, steps were taken to foster successful screening adoption of the screening. A simple screening instrument and clinical protocols designed to be easily integrated into the ED routine were developed. Training was brief and available through multiple channels, including in-person by a site trainer or online. Sites used widely available performance improvement methodologies, including PDCA cycles, for integrating the protocols into routine care and monitoring performance.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations with this study. The participating EDs, though quite diverse, may not represent the nation’s EDs. Further study will be needed to examine whether these protocols, and their subsequent increase in risk detection, can be successfully translated to other EDs.

The RAs were not blinded to study phase. The most important bias this could have caused was to artificially inflate the improvements in suicide risk screening and detection. However, the authors reduced the potential for this bias in several ways. First, RAs were trained on research protocols, which were highly structured, designed to minimize the role of RA interpretations, and closely monitored using both site-specific and centralized quality assurance procedures. Second, RAs were not involved in any of the intervention training or activities. Finally, RAs interviewed all patients who screened positive on the chart to validate the documentation with the patient. If the RAs had been influenced by their knowledge of phase and artificially inflated the documentation of positive screenings, there would have been more patients identified as a positive screen on the chart but who denied any intentional self-harm. This rarely happened (less than 1% of the time across the study).

The study did not randomize individuals or sites due to study design, ethical, and legal considerations (described in Methods paper18). The quasi-experimental design could have introduced a change in clinician behavior simply as a result of being observed (Hawthorne Effect). There was no way to eliminate or measure this, but research protocols were designed to be unobtrusive. The random chart reviews captured data from all days and times to provide an indicator of performance less likely to be influenced by RA presence. Finally, the time series plots show a trend of performance improving over time, which is the opposite of tapering trends usually observed with a Hawthorne Effect as clinicians acclimate to being observed.

The RAs were trained to first identify any documentation of intentional self-harm, whether it was specifically noted as suicidal or not, and to interview these patients to ascertain whether the self-harm was suicidal. This was done because clinical documentation may be inadequate to determine intent. Relying on RAs to ascertain if the self-harm noted was suicidal based solely on documentation might have excluded valid cases. This would have been especially true during treatment as usual prior to the systematic changes in protocols that trained clinicians to document suicidal ideation and behavior more precisely using the PSS-3. The most likely impact of including only charts with clear documentation of suicidal self-harm would be to artificially inflate the screening rates for Phases 2 and 3 relative to Phase 1. Clinicians simply could have become more specific in their self-harm documentation as a result of training and improved templates, rather than increasing screening. Consequently, the inclusion criterion was broad, followed by direct interview to ascertain whether the intentional self-harm documented was indeed suicidal in nature. Patient interviews and careful examination of PSS-3 response patterns in Phase 3 confirmed that the vast majority of intentional self-harm was composed of recent suicidal ideation or behavior.

Conclusions

Such a remarkable and robust increase in screening by clinicians during routine care in busy EDs, and the subsequent increase in risk detection that would not have been identified if universal screening had not been implemented, has never before been published. This landmark finding, if scaled beyond the ED-SAFE sites, has the potential to dramatically improve identification of nascent suicide risk in a highly vulnerable group, thereby paving the way for applying interventions to reduce subsequent suicidal behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the time and effort of the research coordinators and research assistants from the eight participating sites: Edward Boyer, MD, PhD, who provided evaluations of research and clinical protocols (compensated for effort); Robin Clark, PhD, who advised on health economics related issues (compensated for effort); Barry Feldman, PhD, who led the development and deployment of training materials (compensated for effort); and Brianna Haskins, MS, who assisted with copyediting and formatting the paper (compensated for effort).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) or NIH.

The project described was supported by Award Number U01MH088278 from NIMH. This grant was funded as a cooperative award by NIMH. NIMH was represented on the Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) Steering Committee by Amy Goldstein, PhD. She collaborated with the other committee members and investigators to oversee the conduct of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. NIMH provided Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) oversight of the study. The NIMH DSMB liaison was Adam Haim, PhD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Roles. Study design: EDB, CAC, AFS, MHA, ABG, APM, IWM; Study execution: EDB, SAA, CAC, AFS, MHA, ABG, APM, IWM; Data analysis: EDB, SAA, CAC, AFS, JAE, IWM; Data interpretation: EDB, SAA, CAC, AFS, MHA, ABG, APM, JAE, IWM; Manuscript preparation: EDB, SAA, CAC, AFS, MHA, ABG, APM, JAE, IWM.

Trial Registration. Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (EDSAFE) ClinicalTrials.gov: (NCT01150994) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01150994?term=ED-SAFE&rank=1

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC. Suicide among adults aged 35–64 years – United States, 1999–2010. MMWR. 2013;62(17):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman MM, Pirkis JE, Pearson JL, Sherrill JT. Reflections on expert recommendations for U.S. research priorities in suicide prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3) Supplement 2:S97–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. DHHS Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives for action. Washington, DC: DHHS; 2012. Sep, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint Commission. A follow-up report on preventing suicide: focus on medical/surgical units and the emergency department. JC Sentinel Event Alert Issue. 2010;46:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens PL, Mutter R, Stocks C. Healthcare cost and utilization project statistical brief #92: mental health and substance abuse-related emergency department visits among adults, 2007. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Accessed March 22, 2015]. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb92.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Camargo CA., Jr Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1993–2008. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):297–303. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Bridge JA. Focusing suicide prevention on periods of high risk. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1107–1108. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steeg S, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. The development of a population-level clinical screening tool for self-harm repetition and suicide: the ReACT Self-Harm Rule. Psychol Med. 2012;42(11):2383–2394. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudreaux ED, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Mood disorder screening among adult emergency department patients: a multicenter study of prevalence, associations and interest in treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen MH, Abar BW, McCormick M, et al. Screening for suicidal ideation and attempts among emergency department medical patients: instrument and results from the Psychiatric Emergency Research Collaboration. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43:313–323. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boudreaux ED, Cagande C, Kilgannon H, Kumar A, Camargo CA. A prospective study of depression among adult patients in an urban emergency department. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(2):66–70. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0202. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/PCC.v08n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claassen CA, Larkin GL. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:352–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilgen MA, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Recent suicidal ideation among patients in an inner city emergency department. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2009;39(5):508–517. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gairin I, House A, Owens D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: retrospective study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2003;183(1):28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.183.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):870–877. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Goldstein AB, et al. The emergency department safety assessment and follow-up evaluation (ED-SAFE): methods and design considerations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arias SA, Zhang Z, Hillerns C, et al. Using structured telephone follow-up assessments to improve suicide-related adverse event detection. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(5):537–547. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boudreaux ED, Niro K, Sullivan A, et al. Current practices for mental health follow-up after psychiatric emergency department/psychiatric emergency service visits: a national survey of academic emergency departments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(6):631–633. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.05.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boudreaux ED, Jaques ML, Brady KM, Matson A, Allen MH. Validation of the patient safety screener: results from the Psychiatric Emergency Research Collaboration (PERC)-3. Arch Suicide Res. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corp.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Improvement Resources. [Accessed March 22, 2015]; www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Miller I, Espinola J, et al. Multicenter study of predictors of suicide screening in emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01272.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) [Accessed July 1, 2015]; www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011_ed_web_tables.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.