Abstract

Periconceptional supplementation with folic acid results in a significant reduction in the incidence of neural tube defects (NTDs). Nonetheless, NTDs remain a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, and the mechanism(s) by which folate exerts its protective effects are unknown. Homocysteine is an amino acid that accumulates under conditions of folate-deficiency, and is suggested as a risk factor for NTDs. One proposed mechanism of homocysteine toxicity is its accumulation into proteins in a process termed homocysteinylation. Herein, we used a folate-deficient diet in pregnant mice to demonstrate that there is: (i) a significant inverse correlation between maternal serum folate levels and serum homocysteine; (ii) a significant positive correlation between serum homocysteine levels and titers of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated protein; and (iii) a significant increase in congenital malformations and NTDs in mice deficient in serum folate. Further, in mice administered the folate-deplete diet prior to conception, supplementation with folic acid during the gestational period completely rescued the embryos from congenital defects, and resulted in homocysteinylated protein titers at term that are comparable to that of mice administered a folate-replete diet throughout both the pre- and post-conception period. These results demonstrate that a low-folate diet that induces NTDs also increases protein homocysteinylation and the subsequent generation of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated proteins. These data support the hypotheses that homocysteinylation results in neo-self antigen formation under conditions of maternal folate deficiency, and that this process is reversible with folic acid supplementation.

Introduction

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 live births (Blom and others, 2006). Folic acid has been shown to reduce the risk of several congenital malformations, including NTDs, congenital heart defects, cleft palate and limb defects (Shaw and others, 1995a; Shaw and others, 1995b; Smithells and others, 1976); however, despite decades of research, the underlying mechanism by which folate exerts its protective effect has remained elusive.

Homocysteine is a sulphur-containing amino acid that accumulates under conditions of folate deficiency (Jakubowski and Glowacki, 2011). Elevated maternal homocysteine has been associated with reduced fetal growth (Furness and others, 2011), subfertility (Forges and others, 2007), preeclampsia (Cotter and others, 2001, 2003; Powers and others, 1998), recurrent pregnancy loss (Nelen and others, 2000), and congenital malformations (Mills and others, 1995; Steegers-Theunissen and others, 1995; Wenstrom and others, 2001). One mechanism by which homocysteine exerts toxicity is via the non-enzymatic post-translational incorporation of the highly reactive homocysteine metabolite, homocysteine-thiolactone, into intra- and extra-cellular proteins in a process termed homocysteinylation (Perla-Kajan and others, 2007). Protein homocysteinylation may confer harm to the developing embryo via loss of protein function (Jakubowski, 1999), protein aggregation (Jakubowski, 1999), or via neo-antigen formation with the subsequent activation of an immune response and the formation of autoantibodies directed against homocysteinylated proteins (Jakubowski, 2005).

This study sought to identify the temporal relationship of dietary folate and autoantibody generation during pregnancy. Specifically, the present study aimed to determine whether there is a relationship between maternal serum folate, serum homocysteine, and autoantibodies against homocysteinylated protein, in a modified version of a previously established pregnant mouse model of folate deficiency (Burgoon and others, 2002). We hypothesized that there would be an increase in autoantibodies to homocysteinylated protein subsequent to the administration of a folate-deficient diet. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the level of such autoantibodies could be decreased by post-conception supplementation with folic acid, which would rescue the NTDs and other congenital malformations induced in this model.

Methods

Mouse Housing and Treatment Protocols

All animal experimental procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and were approved by the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee. 6–8 week old female C57Bl/6J mice were housed in a Specific Pathogen Free environment and administered a folate-replete (FR; 1.2mg folic acid/kg) or folate-deficient (FD; 0.1mg folic acid/kg) AIN93-based rodent diet either with or without 1% succinylsulfathiazole (SS) – an antibiotic that reduces the synthesis of folate by intestinal bacteria.

Mice were housed on wire-bottomed cages to prevent coprophagy and fed their respective diets for a period of six weeks prior to being transferred to normal rodent bedding for mating with 8 to 12 week old C57B1/6J males. Pre-conception serum samples were ascertained by means of retro-orbital blood collection via a microhematocrit tube perfomed by an approved technician after 6 weeks on the experimental diet. Mice were inspected daily for the presence of a vaginal plug – the presence of which was designated as day 0.5 of pregnancy. Pregnant mice were maintained on their respective diet throughout gestation until termination on gestational day (GD) 18.5. Uteri were dissected and fetuses were inspected for overt malformations.

Quantification of Serum 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) and Homocysteine

Serum 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), the active form of natural folate, was measured by means of validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an API 3200 (AB SCIEX) triple quadrupole LC/MS/MS system with positive ionisation. Samples were chromatographed on an Agilent Poroshell 120 SB-C18 analytical column (150 × 2.1 mm; 2.7 μm), under a binary gradient condition using mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in milliQ water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Samples were prepared by mixing 20 μl of mouse serum with 10 μl of internal standard (methotrexate; 100 ng/ml) and deproteinized with 60 μl of cold acetonitrile containing antioxidants. After vortexing and centrifugation, samples were dried by vacuum concentration at room temperature. Samples were redissolved in 20 μl of methanol with antioxidants and 10 μl was analyzed with LCMS.

Serum homocysteine was determined by high performance liquid chromatography with fluorometric detection, using a commercially available method (Bio-Rad). Samples were prepared by treatment with tributylphosphine to reduce the disulfide bonds, resulting in free Hcy. The protein was precipitated, after which the supernatant fraction was alkalinized. The samples were then treated with a fluorescent probe for SH groups. A reverse-phase HPLC using isocratic elution was employed to establish the concentrations of Hcy.

Detection of Antibodies against Homocysteinylated Serum Albumin (Anti-Hcy-Alb)

Autoantibodies directed against homocysteinylated albumin were measured after 6 weeks on experimental diet and at termination. Briefly, purified murine albumin (Sigma) was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 0.2 mM EDTA and incubated with 0.2 mM L-Hcy-thiolactone•HCl for 16h at 37°C. The extent of modification was determined by monitoring increases in protein thiol groups with Ellman’s reagent (Sigma). Under these conditions, each Hcy-thiolactone–modified murine blood protein contained 1 M Hcy/mol protein. As a control, 10 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) was employed to block thiol groups in homocysteinylated proteins. Incubation of purified serum albumin and hemoglobin without the addition of L-Hcy-thiolactone•HCl was also employed as an additional control. Polisorp (Nunc) 96-well plates were then coated with 10 μg/ml of homocysteinylated albumin in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer subsequent to buffer exchange via filter centrifugation. An indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed (Perla-Kajan and others, 2008) by adding the mouse serum to the wells. A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti mouse IgG was then used to detect the presence of any autoantibodies directed against homocysteinylated albumin, originating from the mouse serum. 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added and the peroxidase reaction stopped by sulphuric acid. The plate was read on a Tecan plate reader at 450nm.

Statistics

Differences in serum homocysteine and antibodies against homocysteinylated albumin between the groups were compared by means of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparison. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05, and NS denotes not significant. Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (Graphpad Software Inc., USA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated.

Results

A Folate-Deficient Diet Supplemented with Antibiotics Significantly Reduces Maternal Folate Levels and Induces Congenital Malformations Including Neural Tube Defects

The effect of the various experimental diets on maternal serum levels of the predominant form of circulating folate, 5-MTHF, was investigated. Mice administered a folate deficient (FD) diet throughout the pre-conceptional and gestational periods had significantly lower levels of serum 5-MTHF at term (90.1 ± 30.8 ng/ml) compared to mice administered a folate replete (FR) diet (294.6 ± 36.9 ng/ml; p < 0.01; Fig. 1). Mice administered a FD diet with the intestinal antibiotic succinylsulfathiazole (FD+SS) had further reduced serum levels of 5-MTHF (8.5 ± 2.6 ng/ml) than mice given a FR diet (p < 0.001; Fig. 1). This demonstrates that a FD diet alone is not sufficient to completely reduce maternal folate (70% reduction), but that elimination of folate-producing bacteria in addition to a FD diet can dramatically ablate maternal folate levels (97% reduction).

Figure 1.

Maternal serum 5-MTHF levels at term in mice administered a folate-replete diet (FR), folate-deficient diet (FD), folate-deficient diet containing 1% succinylsulfathiazole (FD+SS), and a FD or FD+SS diet for six weeks prior to mating, followed by a FR “rescue” diet during gestation (FD/FR and FD+SS/FR, respectively). One-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

In parallel experiments, we administered a FD or FD+SS diet prior to mating, and then switched to a FR diet for the remainder of the pregnancy (FD/FR or FD+SS/FR, respectively). In these folate re-supplemented mice, there were no longer significant reductions in term serum 5-MTHF levels (FD/FR: 419.8 ± 44.9 ng/ml; FD+SS/FR: 411.3 ± 96.4 ng/ml) compared to mice administered a FR diet throughout both the pre-conception period and throughout gestation (Fig. 1). This demonstrates that folate supplementation during the gestational period is sufficient to restore maternal folate levels at term.

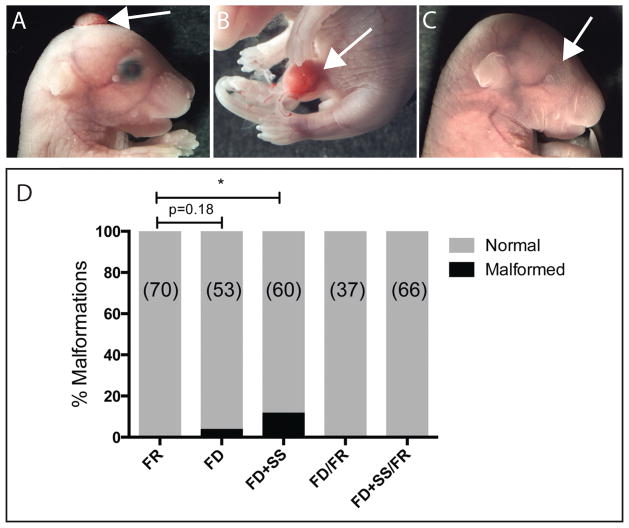

In each of the dietary groups, we also examined the offspring for congenital malformations, consistent with our previous observations that FD alone can induce congenital malformations (Denny and others, 2013a). Mice administered a FD+SS produced offspring bearing a variety of congenital malformations, including: anterior neural tube defects (4/60; Fig. 2A), curly tail (1/60), omphalocele (4/60; Fig. 2B), and anophthalmia (1/60; Fig. 2C). Only 2 of the mice administered a FD diet without SS displayed malformations (omphalocele 1/53; exencephaly 1/53). No congenital malformations were observed in mice fed a FR diet or mice switched from a FD or FD+SS diet to a FR diet following the presence of a mating plug and for the duration of gestation. The total prevalence of fetal malformations is presented in Figure 2D.

Figure 2.

Congenital abnormalities observed in FD+SS E18.5 fetuses included (A) exencephaly, (B) omphalocele, and (C) anophthalmia. (D) Quantification of malformation incidence in the different diet groups. (n) number of fetuses. Data were analysed by Fisher’s exact test. * p < 0.05.

Taken together, these results demonstrate both the ability of folate deprivation to lead to a range of congenital malformations, and the therapeutic effects of folate supplementation within the gestational period to rescue these malformations. While there was a significant decrease in maternal serum 5-MTHF in the FD group (Fig. 1), this did not correspond to a significant increased incidence of malformations (Fig. 2D). However, further reduction of maternal 5-MTHF by the addition of antibiotic (FD+SS), led to a significant increase in the prevalence of congenital malformations (Fig. 2D).

Maternal Folate Deficiency is Associated with Elevated Serum Homocysteine

Folate, in the form of 5-MTHF, reconstitutes homocysteine (Hcy) to methionine in the methylation cycle (Mato and others, 2008). Thus, 5-MTHF and Hcy levels are often observed to have an inverse correlation with each other. We next examined whether alterations in maternal folate levels in our model led to a corresponding inverse change in Hcy levels. Mice administered a FD+SS diet had significantly elevated serum homocysteine concentrations (47.36 ± 7.84 uM; p <0.01) compared to mice administered a FR diet (21.02 ± 3.72 uM; Fig. 3A). However, despite the decrease in maternal 5-MTHF in the FD group, this did not correspond to a significant increase in Hcy (24.53 ± 2.52 uM), compared to mice administered a FR diet (Fig. 3A). As expected, mice administered a FD or FD+SS diet in the pre-conception period and then swapped to a FR diet from E0.5 through gestation did not have significantly different serum homocysteine levels at term (FD/FR: 16.16 ± 2.54 uM; FD+SS/FR: 21.26 ± 3.78 uM) compared to mice administered a FR diet throughout both the pre-conception and gestational periods (Fig. 3A). This demonstrated that the resumption of folate in maternal serum (Fig. 1) did correspond with a decrease in Hcy levels (Fig 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Maternal homocysteine levels at term, following a range of dietary regimens. One-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; ** p<0.01; ns, not significant. (B) Maternal serum homocysteine levels with respect to 5-MTHF levels. Simple linear regression yielded r2 = 0.18. Inset: data plotted on log-log axes. Non-linear regression analysis yielded r2 = 0.49, p = 0.00002.

The relationship between 5-MTHF and Hcy levels in the five treatment groups was further examined. We found that at high levels of 5-MTHF, there were comparatively low levels of Hcy, and at very low levels of 5-MTHF, there were very high levels of Hcy. However, the data did not conform to a linear regression fit (r2 = 0.18). Instead, the relationship was investigated with a bi-logarithmic non-linear regression, which demonstrated an inverse relationship between 5-MTHF and Hcy (Fig 3B inset; r2 = 0.49, n = 29, p = 0.00002). These data highlight the important observation that a threshold of folate deficiency is required to achieve a significant increase in Hcy, rather than a strictly linear relationship.

Maternal Folate Deficiency is Associated with Elevated Levels of Autoantibodies Against Homocysteinylated Proteins

To test our hypothesis that elevated homocysteine secondary to a folate-deficiency would result in autoantibody production against homocysteinylated proteins, we developed an indirect ELISA to detect serum autoantibodies against homocysteinylated albumin (anti-Hcy-Albumin). In mice administered a FD+SS diet there was a significant increase in anti-Hcy-Albumin antibodies (0.164 ± 0.037 Abs450nm) compared to mice administered a FR diet at term (0.037 ± 0.009 Abs450nm; p < 0.01; Fig. 4A). When the FD+SS pre-conception diet was rescued with a FR diet throughout gestation, this resulted in comparable levels of anti-Hcy-Albumin antibodies (0.079 ± 0.023) to mice administered a FR throughout the study (Fig. 4A). There was no significant differences in the concentration of anti-Hcy-Albumin antibodies in mice administered a FD diet without SS (0.090 ± 0.017), or a FD diet followed by a FR diet from E0.5 through gestation (0.090 ± 0.016), compared to mice administered a FR diet (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) Maternal levels of antibodies directed against homocysteinylated albumin (Anti-Hcy-albumin) at term, following a range of dietary regimens. One-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; ** p<0.01; ns, not significant. (B) Maternal Anti-Hcy-albumin levels are positively correlated with homocysteine levels in maternal serum. Pearson’s correlation r = 0.46, p = 0.0033.

We also examined the relationship between maternal homocysteine and anti-homocysteinylated-albumin antibodies. There was a significant positive correlation between serum Hcy levels and titers of anti-Hcy-Albumin antibodies at term (Pearson r = 0.459; p = 0.003; n = 39; Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that elevated homocysteine, due to maternal folate deficiency, results in increased generation of autoantibodies directed against homocysteinylated proteins such as albumin.

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine whether there is a direct link between elevated homocysteine levels and antibodies against homocysteinylated protein by employing a folate-deficient mouse model of pregnancy. In concordance with previous studies (Burgoon and others, 2002), we found that there was a significant increase in plasma homocysteine in pregnant mice administered a FD+SS diet throughout both the preconceptional and gestational period. The relationship between high homocysteine and poor pregnancy outcomes, independent of blood folate, has been established in both animal models and in human clinical populations (Bergen and others, 2012; Demir and others, 2012; Dhobale and others, 2012; Gadhok and others, 2011; Kim and others, 2012; van Mil and others, 2010). Administration of homocysteine to pregnant mice in the early stages of gestation has been demonstrated to cause fetal growth restriction, congenital abnormalities and increased fetal lethality (Han and others, 2009). Homocysteine has been found to have direct toxic effects in both in vitro and in vivo studies by means of impairing endothelium-dependent relaxation, upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, acting as a pro-thrombotic agent, and inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress (Perla-Kajan and others, 2007). However, the precise means by which homocysteine may induce harm in pregnancy remains unknown (Murphy and Fernandez-Ballart, 2011).

One mechanism by which elevated homocysteine has been proposed to cause toxicity is by means of protein homocysteinylation and subsequent autoantibody formation (Taparia and others, 2007; Undas and others, 2005; Undas and others, 2004). The present study demonstrated that mice on a FD+SS diet had a significantly higher serum concentration of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated albumin than mice administered a FR diet. The present study is the first to demonstrate the presence of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated proteins in a mouse model and, significantly, the first to experimentally demonstrate that autoantibodies against homocysteinylated proteins can be induced by a dietary folate-deficiency.

High concentrations of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated albumin have previously been shown to be associated with ischemic stroke (Undas and others, 2004) and the early development of coronary artery disease in human clinical populations (Undas and others, 2005). Autoantibodies against homocysteinylated proteins have been hypothesized to confer harm by triggering an immune response and/or by acting as blocking antibodies (Taparia and others, 2007; Undas and others, 2004). A role for autoimmunity in folate-deficiency associated pregnancy complications has previously been established, with autoantibodies against placental folate receptors found in women with a current or previous pregnancy complicated by a NTD (Cabrera and others, 2008; Rothenberg and others, 2004; Schwartz, 2005). Administration of folate receptor antibodies to rats results in dose-dependent embryonic damage and lethality, which at low doses can be prevented by the administration of folic acid, and at larger doses can be prevented by the anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid, dexamethasone (da Costa and others, 2003). It is proposed that protein homocysteinylation may be a mechanism by which such autoantibodies against the folate receptor are formed (Taparia and others, 2007), and folate receptor homocysteinylation represents a potential future focus of investigation.

The potency of a FD diet alone, in the absence of the antibiotic succinylsulfathiazole, was also evaluated with regards to serum levels of the folate metabolite 5-MTHF, homocysteine, and autoantibodies against homocysteinylated protein. It had previously been proposed that succinylsulfathiazole could be removed from diets in experiments involving folate-deficient mouse models, providing the mice remained on wire-bottomed cages to prevent coprophagy (Burgoon and others, 2002). This recommendation was based on the finding that mice administered succinylsulfathiazole alone had no significant difference in blood folate levels, homocysteine concentrations, or reproductive outcomes compared to mice administered a normal FR diet (Burgoon and others, 2002). In the present study, mice who were administered a FD diet in the absence of succinylsulfathiazole and maintained on wire-bottomed cages did not have significantly elevated serum homocysteine, compared to mice administered a FR diet. Similarly, there were no significant differences in autoantibodies against homocysteinylated albumin. In addition, there were fewer congenital abnormalities in mice administered a FD alone compared to mice administered a FD+SS diet. The conclusion that can be drawn from these data is that a threshold of folate deficiency must be reached in order to have significant implications for homocysteine and autoantibody levels, in addition to birth defects. Thus, in light of the results of the present study, we recommend that future studies employing folate-deficient mouse models are likely to require both a FD diet and the antibiotic succinylsulfathiazole in order to assess the effects of interventions on blood factors and fetal outcomes. These studies also highlight the importance of analyzing both 5-MTHF and homocysteine in human NTD cohorts to gain a broader picture of folate status in these individuals.

A range of congenital malformations was observed in the present study. These included exencephaly, microcephaly, curly tail, omphalocele and anophthalmia. Previously, we reported that combined loss of the innate immune receptor C5aR with dietary folate deficiency led to a similar range of malformations (Denny and others, 2013a). It was noted in the present study, that the FD+SS alone, while inducing a similar array of malformations, were often less severe than those that were observed secondary to folate deficiency in the C5aR knockout mice. Specifically, we observed omphalocele in the FD+SS group, whereas we saw the more severe defect gastroschisis in the C5aR−/−/FD+SS treatment group (Denny and others, 2013a). This contrasts to a study by Burgoon and colleagues where despite developmental delays evidenced at E16, no omphaloceles were observed past E18 (Burgoon and others, 2002). Similarly, Burgoon and colleagues only reported 1 case of exencephaly out of a total of 250 live embryos evaluated, with one additional case in a deceased fetus, and just one case of cleft palate out of 74 embryos examined (Burgoon and others, 2002). The increased incidence of malformations observed in the present study may be attributable to the increased time that the mice in the present study spent on the FD+SS diet prior to mating – 6 weeks versus 4 weeks in the Burgoon study. It may also reflect differences in the mouse strains used. The current study utilized the C57Bl/6J inbred strain, whereas the Burgoon study employed the outbred ICR strain. It is well established that different mouse strains can have varied susceptibility to the occurrence of spontaneous and teratogen-induced NTDs (Harris and Juriloff, 2010). In the case of diabetes-induced NTDs, C57Bl/6 mice were less responsive than ICR mice to this form of teratogenicity (Pani and others, 2002). However, in a study examining neural crest cell teratogenicity, C57Bl/6 mice were more susceptible than ICR mice to ethanol exposure (Chen and others, 2000). Our data suggest, at least in the context of folate-sensitive NTDs, that the C57Bl/6 mouse strain was more susceptible than the ICR mice, reported previously (Burgoon and others, 2002).

Finally, the present study also demonstrated that a “rescue” diet, in which a pre-conception FD+SS diet was replaced with a FR diet during gestation, resulted in serum levels of homocysteine and autoantibody concentrations that were not significantly different from controls. Concomitantly, this administration of folic acid during gestation also prevented the congenital abnormalities. Together, these results highlight the importance of folic acid supplementation during the antenatal period in this mouse model of folate-deficiency during pregnancy.

In conclusion, maternal folate deficiency due to a FD+SS dietary regime, and consequent increased plasma homocysteine, is associated with an increase in the formation of autoantibodies against homocysteinylated protein in pregnancy. However the implications of this remain uncertain. Homocysteinylated proteins may potentially confer fetal harm by activating the immune system or acting as blocking antibodies, however this remains to be investigated (Denny and others, 2013b). We recommend that future studies in this area aim to delineate the individual contributions of folate-deficiency, elevated homocysteine, and autoantibodies against homocysteinylated proteins in contributing towards poor fetal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project Grant APP1082271) and an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT110100332 to TMW), as well as support in part by NIH grants HD067244 and NS076465 to RHF.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bergen NE, Jaddoe VW, Timmermans S, Hofman A, Lindemans J, Russcher H, Raat H, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Steegers EA. Homocysteine and folate concentrations in early pregnancy and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: the Generation R Study. BJOG. 2012;119(6):739–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom HJ, Shaw GM, den Heijer M, Finnell RH. Neural tube defects and folate: case far from closed. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(9):724–731. doi: 10.1038/nrn1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon JM, Selhub J, Nadeau M, Sadler TW. Investigation of the effects of folate deficiency on embryonic development through the establishment of a folate deficient mouse model. Teratology. 2002;65(5):219–227. doi: 10.1002/tera.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera RM, Shaw GM, Ballard JL, Carmichael SL, Yang W, Lammer EJ, Finnell RH. Autoantibodies to folate receptor during pregnancy and neural tube defect risk. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;79(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Periasamy A, Yang B, Herman B, Jacobson K, Sulik KK. Differential sensitivity of mouse neural crest cells to ethanol-induced toxicity. Alcohol. 2000;20(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter AM, Molloy AM, Scott JM, Daly SF. Elevated plasma homocysteine in early pregnancy: a risk factor for the development of severe preeclampsia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;185(4):781–785. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter AM, Molloy AM, Scott JM, Daly SF. Elevated plasma homocysteine in early pregnancy: a risk factor for the development of nonsevere preeclampsia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;189(2):391–394. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00669-0. discussion 394–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa M, Sequeira JM, Rothenberg SP, Weedon J. Antibodies to folate receptors impair embryogenesis and fetal development in the rat. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2003;67(10):837–847. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir B, Demir S, Pasa S, Guven S, Atamer Y, Atamer A, Kocyigit Y. The role of homocysteine, asymmetric dimethylarginine and nitric oxide in pre-eclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(6):525–528. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.693985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny KJ, Coulthard LG, Jeanes A, Lisgo S, Simmons DG, Callaway LK, Wlodarczyk B, Finnell RH, Woodruff TM, Taylor SM. C5a Receptor Signaling Prevents Folate Deficiency-Induced Neural Tube Defects in Mice. J Immunol. 2013a;190(7):3493–3499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny KJ, Jeanes A, Fathe K, Finnell RH, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. Neural tube defects, folate, and immune modulation. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2013b;97(9):602–609. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhobale M, Chavan P, Kulkarni A, Mehendale S, Pisal H, Joshi S. Reduced Folate, Increased Vitamin B(12) and Homocysteine Concentrations in Women Delivering Preterm. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61(1):7–14. doi: 10.1159/000338473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forges T, Monnier-Barbarino P, Alberto JM, Gueant-Rodriguez RM, Daval JL, Gueant JL. Impact of folate and homocysteine metabolism on human reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(3):225–238. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness D, Fenech M, Dekker G, Khong TY, Roberts C, Hague W. Folate, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6 and homocysteine: impact on pregnancy outcome. Matern Child Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadhok AK, Sinha M, Khunteta R, Vardey SK, Upadhyaya C, Sharma TK, Jha M. Serum homocysteine level and its association with folic acid and vitamin B12 in the third trimester of pregnancies complicated with intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Lab. 2011;57(11–12):933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Serrano MC, Lastra-Vicente R, Brinez P, Acharya G, Huhta JC, Chen R, Linask KK. Folate rescues lithium-, homocysteine- and Wnt3A-induced vertebrate cardiac anomalies. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(9–10):467–478. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, Juriloff DM. An update to the list of mouse mutants with neural tube closure defects and advances toward a complete genetic perspective of neural tube closure. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2010;88(8):653–669. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski H. Protein homocysteinylation: possible mechanism underlying pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. FASEB J. 1999;13(15):2277–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski H. Anti-N-homocysteinylated protein autoantibodies and cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43(10):1011–1014. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski H, Glowacki R. Chemical biology of homocysteine thiolactone and related metabolites. Adv Clin Chem. 2011;55:81–103. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-387042-1.00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MW, Hong SC, Choi JS, Han JY, Oh MJ, Kim HJ, Nava-Ocampo A, Koren G. Homocysteine, folate and pregnancy outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(6):520–524. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.693984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mato JM, Martinez-Chantar ML, Lu SC. Methionine metabolism and liver disease. Annual review of nutrition. 2008;28:273–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JL, McPartlin JM, Kirke PN, Lee YJ, Conley MR, Weir DG, Scott JM. Homocysteine metabolism in pregnancies complicated by neural-tube defects. Lancet. 1995;345(8943):149–151. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MM, Fernandez-Ballart JD. Homocysteine in pregnancy. Adv Clin Chem. 2011;53:105–137. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-385855-9.00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelen WL, Blom HJ, Steegers EA, den Heijer M, Thomas CM, Eskes TK. Homocysteine and folate levels as risk factors for recurrent early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(4):519–524. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Horal M, Loeken MR. Polymorphic susceptibility to the molecular causes of neural tube defects during diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2002;51(9):2871–2874. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perla-Kajan J, Stanger O, Luczak M, Ziolkowska A, Malendowicz LK, Twardowski T, Lhotak S, Austin RC, Jakubowski H. Immunohistochemical detection of N-homocysteinylated proteins in humans and mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62(7):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perla-Kajan J, Twardowski T, Jakubowski H. Mechanisms of homocysteine toxicity in humans. Amino Acids. 2007;32(4):561–572. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RW, Evans RW, Majors AK, Ojimba JI, Ness RB, Crombleholme WR, Roberts JM. Plasma homocysteine concentration is increased in preeclampsia and is associated with evidence of endothelial activation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1998;179(6 Pt 1):1605–1611. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg SP, da Costa MP, Sequeira JM, Cracco J, Roberts JL, Weedon J, Quadros EV. Autoantibodies against folate receptors in women with a pregnancy complicated by a neural-tube defect. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(2):134–142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RS. Autoimmune folate deficiency and the rise and fall of “horror autotoxicus”. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(19):1948–1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Lammer EJ, Wasserman CR, O’Malley CD, Tolarova MM. Risks of orofacial clefts in children born to women using multivitamins containing folic acid periconceptionally. Lancet. 1995a;346(8972):393–396. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, O’Malley CD, Wasserman CR, Tolarova MM, Lammer EJ. Maternal periconceptional use of multivitamins and reduced risk for conotruncal heart defects and limb deficiencies among offspring. American journal of medical genetics. 1995b;59(4):536–545. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ. Vitamin dificiencies and neural tube defects. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51(12):944–950. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.12.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegers-Theunissen RP, Boers GH, Blom HJ, Nijhuis JG, Thomas CM, Borm GF, Eskes TK. Neural tube defects and elevated homocysteine levels in amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995;172(5):1436–1441. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taparia S, Gelineau-van Waes J, Rosenquist TH, Finnell RH. Importance of folate-homocysteine homeostasis during early embryonic development. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(12):1717–1727. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undas A, Jankowski M, Twardowska M, Padjas A, Jakubowski H, Szczeklik A. Antibodies to N-homocysteinylated albumin as a marker for early-onset coronary artery disease in men. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(2):346–350. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undas A, Perla J, Lacinski M, Trzeciak W, Kazmierski R, Jakubowski H. Autoantibodies against N-homocysteinylated proteins in humans: implications for atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1299–1304. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000128412.59768.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mil NH, Oosterbaan AM, Steegers-Theunissen RP. Teratogenicity and underlying mechanisms of homocysteine in animal models: a review. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(4):520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenstrom KD, Johanning GL, Johnston KE, DuBard M. Association of the C677T methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation and elevated homocysteine levels with congenital cardiac malformations. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;184(5):806–812. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.113845. discussion 812-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]