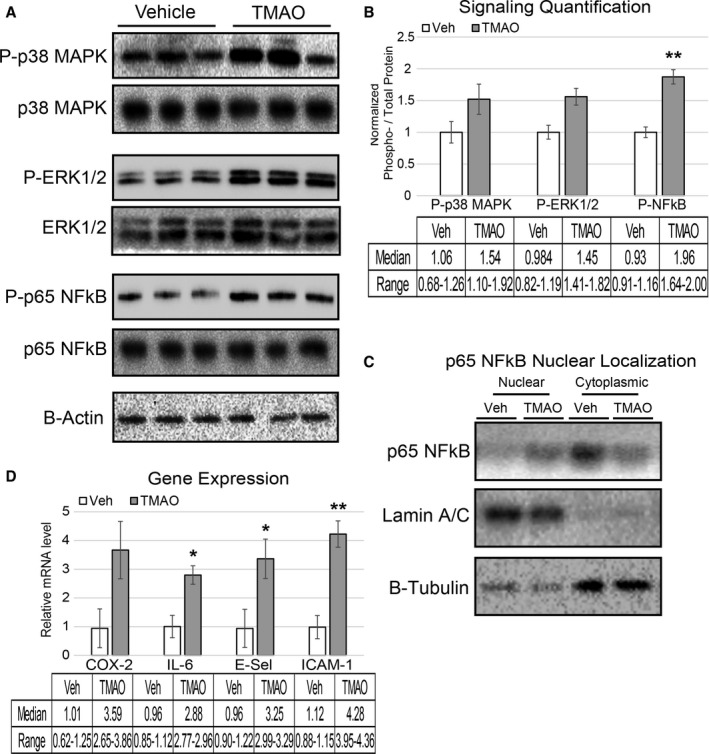

Figure 2.

Acute TMAO injection causes activation of signaling cascades and elevated inflammatory gene expression. A and B, LDLR −/− female mice were fasted for 4 hours and then injected with vehicle or TMAO (86 μmol). Aortas were harvested 30 minutes following injection and immunoblotted (A) and quantified (B) for phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (Thr‐180/Tyr‐182), ERK1/2 (Thr‐202/Try‐204), and p65 NFkB (Ser536). n=3, nonparametric t test using a Mann–Whitney U test was performed for comparisons. Median and range are reported for each group. C, Lysate from the same aortas was fractionated into nuclear and cytosolic compartments and immune‐probed for the presence of p65 NFkB with lamin A/C and β‐tubulin, indicating the purity of the nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively. D, A separate cohort of LDLR −/− mice underwent the same fasting–injection procedure, and then aortas were harvested 5 hours after injection, and qPCR was used to quantify expression levels of inflammatory genes. All data were expressed as mean±SEM. Immunoblot quantification was normalized to P‐residue/total protein, with β‐actin serving as a loading control; qPCR genes normalized to RPL13A expression. n=3, nonparametric t test using a Mann–Whitney U test was performed for comparisons. Median and range are reported for each group; *P<0.05; **P<0.01. ERK1/2 indicates extracellular signal–related kinase 1/2; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinase; NFkB, nuclear factor‐κB; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TMAO, trimethylamine N‐oxide; TNF‐a, tumor necrosis factor α; Veh, vehicle.