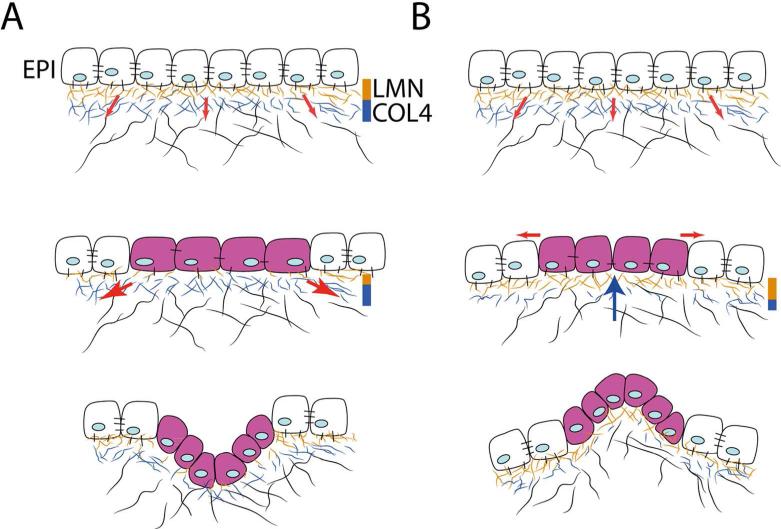

Fig. 5.

Mechanical model explaining epithelial invaginations and evaginations. (A) Top: Prior to budding, the basement membrane underlying the epithelium (EPI) is well-structured and contains abundant laminin (LMN) and collagen (COL4) fibers. Tension exerted (red arrows) on the extracellular matrix by the mesenchymal cells is resisted and the epithelium remains stabilized. Middle: At sites where laminin is reduced, epithelial cells are stretched (purple cells) due to tension exerted by mesenchymal cells (red arrows), which triggers proliferation. Bottom: At these sites the epithelium invaginates (adapted from Ingber 2006). (B) This diagram illustrates how the mechanical hypothesis described in A can be applied to explain evaginations. Top: The epithelium is stabilized by a well-formed basement membrane (see A Top). Middle: At sites where COL4 is reduced, tension exerted on the epithelium from the extracellular matrix is relaxed. At these sites, a “pushing” force (blue arrow) exerted by the growing mesenchyme may generate tension along the outer surface of the epithelium (red arrows), triggering proliferation (purple cells) or other cell behaviors (see Lao et at. 2015) Bottom: At these sites, the epithelium evaginates.