Abstract

Odontogenic fibromyxoma (OFM) is a benign, locally invasive and aggressive nonmetastasizing neoplasm of jaw bones. They are considered relatively rare and known to be derived from embryonic mesenchymal elements of dental origin. Treatment of OFM depends on the size of the lesion and on its nature and behavior. Varying treatment modalities ranging from curettage to radical excision have been documented. Aim; This paper is a review of management of 8 pediatric patients with histologically diagnosed OFM at a Nigerian tertiary health care facility. This was a retrospective study of all patients aged 15 years and below who presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, over a 5-year period (January 2008 to December 2012), with a histologic diagnosis of OFM. The information obtained included patients' demographics, as well as their clinical characteristics such as the anatomical site and side of lesions. Other information collated included presenting features, the onset of symptoms, type of treatment carried out, as well as treatment outcome. The data were analyzed and the results presented as frequencies and percentages. Among the 8 patients with OFM, more males (n = 5/8; 62.5%) were affected than females (n = 3/8; 37.5%). The mandible (n = 5/8; 62.5%) was the most frequent site of occurrence, and the anterior mandible was the most favored location (n = 4/8; 50%). Seven patients had excision of the lesion with peripheral ostectomy of the underlying bone while only one patient had a bone resection. These patients have been followed up for at least 1 year, and no recurrence was observed throughout the follow-up period. OFM causes gross facial disfigurement and may result in the destruction of the entire jaw bone; the impact of which may be grave for a growing child. Prompt surgical intervention and follow-up have proven to be adequate management protocol.

Keywords: Odontogenic fibromyxoma, Odontogenic tumor, Pediatric

Introduction

Odontogenic fibromyxoma (OFM) is a benign, locally invasive and aggressive nonmetastasing neoplasm of jaw bones.[1] It represents about 1–17.7% of all odontogenic tumors.[2] OFM is the second most common odontogenic tumor with incidence of approximately 0.07 new cases per million per year.[3] The World Health Organization classification of benign odotogenic tumors grouped OFM as benign tumors of ectomesenchymal origin with or without odontogenic epithelium.[4]

They are considered relatively rare, and known to be derived from embryonic mesenchymal elements of dental origin. These may include dental papilla, dental follicle or periodontal ligaments. The evidence of its odontogenic origin may be related to its exclusive location in the tooth bearing areas of the jaws. It occurs more in the mandible than the maxilla.[4] OFM have been reported in other parts of the body including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and heart (mainly left atrium) and this finding has challenged the assumed odontogenic nature of these lesions.[4]

It usually present as an asymptomatic slow growing lesion with infiltrative growth pattern causing destruction of medullary bone and expansion of cortical bone. It occurs mostly in young adults in their second to third decades of life being rare in children <10 years and adults over 50 years.[4,5] The asymptomatic nature of these lesions encourages late presentation. When very large in the orofacial region, it can cause gross facial disfigurement and functional derangement with specific reference to feeding.

This lesion often may be an incidental discovery on routine dental checkup except for large lesions which might cause tooth displacement and cortical bone expansion which might necessitate patient presentation. Aside from evidence of bone expansion and osteolytic changes, radiological examination with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT), and conventional plain radiography do not show pathognomonic features that are specific to diagnosis of OFM. However their findings often suggest differentials that may include ameloblastoma, central haemagioma, odontogenic, and aneurysmal bone cysts.[6,7] Plain radiographic appearance of OFM may vary from unilocular to multilocular radiolucency with well-defined borders and fine bony trabeculae as a result of bone destruction.[5] This is often described as “honey comb,” “soap bubble,” “tennis racket,” “wispy”, or “spider web” appearance.[1,4] Immunohistochemical analysis shows low mitotic activity to Ki-67,[8] presence of vimentin[9] and a high concentration of hyaluronic acid.[10]

Treatment of OFM depends on size of the lesion and on its nature and behavior. Varying treatment modalities ranging from curettage to radical excision have been documented.[1,5] Complete surgical excision, using curettage and peripheral ostectomy alone has been argued to be insufficient treatment as the lesion is not encapsulated.[6] Due to lack of capsule, a conservative treatment modality may result in infiltration of myxomatous tissue to adjacent bone leading to a high recurrence rate.

This paper is a review of management of 8 pediatric patients with histologically diagnosed OFM at a Nigerian tertiary health care facility.

Methods for the Case Series

This was a retrospective study of all patients aged 15 years and below who presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, over a 5-year period (January 2008 to December 2012) with a histologic diagnosis of OFM. The information obtained included patients' demographics, as well as their clinical characteristics such as the anatomical site and side of lesions. Other information collated included presenting features, onset of symptoms, type of treatment carried out, as well as treatment outcome. The data were analyzed and the results presented as frequencies and percentages.

Results

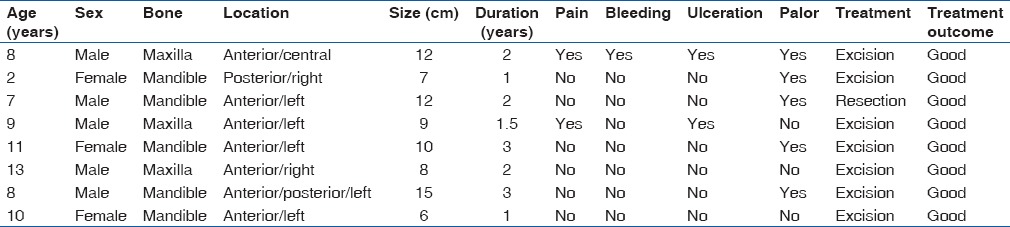

A total of 96 odontogenic tumors were seen within the period of study, out of which 31 were OFM. Only 8 of this number were 15 years and below thus giving a prevalence of 32.3% for OFM and 8.3% for pediatric OFM. Of the 8 patients with OFM, more males (n = 5/8; 62.5%) were affected than females (n = 3/8; 37.5%). The mandible (n = 5/8; 62.5%) was the most frequent site of occurrence and the anterior mandible was the most favored location (n = 4/8; 50%). The three maxillary lesions were located on the anterior position [Table 1]. All except 2 patients presented with painless jaw swelling. Mucosal ulceration and bleeding were less frequently seen [Table 1]. Palor (n = 5/8; 62.5%) was a common feature. Seven patients had excision of the lesion with peripheral ostectomy of the underlying bone while only one patient had bone resection. These patients have been followed up for at least 2 years and no recurrence was observed throughout the follow-up period.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 8 patients with odontogenic fibromyxoma

Discussion

OFM of the jaws was first described by Thoma and Goldman in 1947.[11] It is a rare benign tumor occurring in tooth-bearing areas of the mandible and maxilla and characterized by slow growth and bone invasions. Peltola et al.[12] noted posterior region of the jaws as the most common site of occurrence and a similar distribution pattern in males and females. This was in contrast to our findings; the rarity of these lesions and a small sample size in our study may account for these disparities. OFM is a relatively rare entity and even more so in the pediatric population. Aquilino et al.,[13] reported a greater occurrence in the second and third decades of life and a rarity in children and in adults older than 50 years. This was corroborated by Sivakumar et al.[4] and Ajayi et al.[5] This tumor causes gross facial deformity and may result in loss of self-esteem [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative photograph of an 8-year-old boy with odontogenic fibromyxoma involving the maxilla. Note the gross disfiguring nature of the tumor. (b) Postoperative photograph of the same patient 2 years postsurgery

Figure 2.

(a) Preoperative photograph of a 7-year-old boy with odontogenic fibromyxoma involving the mandible. Note the tumor has filled the whole mouth thus impeding adequate feeding. (b) Postoperative view of the same patient 2 years postsurgery

CT scan was requested for our patients but only 3 patients could afford to take it. The CT revealed areas of bi-cortical jawbone destruction, with a displacement of some dental elements [Figure 3]. Digital plain radiography was done for subjects who could not afford CT and it revealed extensive radiolucent and multilocular areas with precise borders [Figure 4]. The radiologic pattern in our patients was that of a soap bubble, honey comb, or tennis racket appearance. This was consistent with the reports in the literature.[5] Aquilino et al.[13] noted that the radiologic diagnosis of OFM is sometimes difficult because of variable radiographic characteristics of the different developmental stages. They advised advanced imaging studies like CT or MRI to clearly define the margins of the tumor, determine degree of adjacent tissue invasion and ultimately facilitate surgery. This suggestion was corroborated by Kheir et al.[14] in their study which compared the imaging characteristics of OFM in 33 patients using the 3 imaging modalities. The lack or nonaffordability of these advanced imaging modalities in developing regions should call for a strong and effective follow-up as part of management protocol.

Figure 3.

A three-dimensional computerized tomographic view of a 10-year-old girl with odontogenic fibromyxoma involving the mandible. Note the gross destruction of the involved segment

Figure 4.

Oblique lateral radiographic view of the 7-year-old boy [Figure 2] a showing gross destruction of the mandible

Consistent histologic finding in our patients was that of an unencapsulated lesion with the proliferation of fusiform and stellate-pattern or spindle-shaped cellular components dispersed in abundant myxomatous stroma with a few collagen fibers. These undifferentiated mesenchymal cells were noted by Adekeye et al.[15] to exhibit abundant extracellular production of ground substance and thin fibrils which are capable of fibroblastic differentiation. The lesion is thus classified as OFM or odontogenic myxofibroma depending on differentiation pattern, whether predominantly myxoid or fibrous, respectively.

The majority of OFM in our study were asymptomatic, although some patients presented with progressive pain in lesions invading into surrounding tissues with eventual neurological disturbance. Another cause of pain in OFM, may be the ulcerations caused by the indenting teeth of the opposing jaw as observed in two of the cases. Our finding of lesions affecting the maxilla being less frequent but exhibiting more aggressive behavior compared to mandibular lesions was consistent with the findings in the literature.[16,17] Palor which was noticeable in majority of our patients may have been related to both the chronic blood loss from areas of ulceration of the lesion and possibly malnourishment from the inability to feed well. The latter is a consequence of poor masticatory and swallowing ability, as well as incompetence of lip seal due to obstructive effect of the tumor. The impact of poor nutrition may be very significant in a growing child. Management of anemia in our subjects prior to surgery added to the overall cost of treatment. Our management protocol necessitated preoperative optimization involving blood transfusions in these patients.

Both conservative and radical surgical treatments have been described for the management of odontogenic myxoma. Kawase-Koga et al.[6] in a review of the literature noted that conservative management (enucleation, curettage, and marginal resection) resulted in a greater recurrence rate compared to the radical treatment (jaw resection) after a period of 46.4 months follow-up.

The choice of a more conservative treatment for our patients in this study was because of their ages and assured availability for postoperative reviews. The radiographic imaging of all our patients showed distinct margins between the lesion and normal bone. This was also consistent with the intraoperative (a distinct cleavage point) findings in our experience and has been attributed to a function of periosteum acting as a barrier to prevent soft tissue infiltration.[14] The soft tissue is compressed thus acting like a pseudocapsule, even with complete cortical loss. A more aggressive treatment was employed in the 7-year-old boy [Figure 2] who already had significant bone destruction. This necessitated an extra oral surgical access with attendant aesthetic complication, longer hospitalization time, and higher cost of treatment. During the operative session, the periosteum was preserved in all our patients, and this has been documented to encourage spontaneous bone regeneration especially in younger patients.[18,19] The factors guiding the choice of surgical approach in this study, in a prioritized order, included ease of intraoral surgical access to normal bone, conservative versus radical surgery, and aesthetic demands. Intra oral approach was preferred for anterior jaw lesions that did not restrict access to normal bone, irrespective of its size [Figure 1a] and where esthetic demands were high especially in the female subjects. The case in Figure 2 was surgically resected using the extraoral access for the reasons previously stated.

The aggressive behavior of OFM is a strong indication to rule out malignancy and an indication to advocate early intervention to prevent significant bone destruction in a growing child which may be associated with deformity and its antecedent psychosocial impact. There is also a need for postoperative follow-up as OFM has been known to recur when a more conservative treatment approach is adopted.

Conclusion

OFM causes gross facial disfigurement and may result in the destruction of the entire jaw bone; the impact of which may be grave for a growing child. Prompt surgical intervention and follow-up have proven to be adequate management protocol.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Leiser Y, Abu-El-Naaj I, Peled M. Odontogenic myxoma – Acase series and review of the surgical management. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37:206–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker BF. Odontogenic myxoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1999;16:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon EN, Merkx MA, Vuhahula E, Ngassapa D, Stoelinga PJ. Odontogenic myxoma: a clinicopathological study of 33 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:333–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivakumar G, Kavitha B, Saraswathi TR, Sivapathasundharam B. Odontogenic myxoma of maxilla. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:62–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajayi OF, Ladeinde AL, Adeyemo WL, Ogunlewe MO. Odontogenic tumors in Nigerian children and adolescents – A retrospective study of 92 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:39. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-2-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawase-Koga Y, Saijo H, Hoshi K, Takato T, Mori Y. Surgical management of odontogenic myxoma: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumi Y, Miyaishi O, Ito K, Ueda M. Magnetic resonance imaging of myxoma in the mandible: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:671–6. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.108917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich EM, Papaemmanouil S, Koloutsos G, Antoniades H, Antoniades K. Odontogenic fibromyxoma of the maxilla: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2011;2011:238712. doi: 10.1155/2011/238712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo Muzio L, Nocini P, Favia G, Procaccini M, Mignogna MD. Odontogenic myxoma of the jaws: a clinical, radiologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:426–33. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slootweg PJ, van den Bos T, Straks W. Glycosaminoglycans in myxoma of the jaw: a biochemical study. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoma KH, Goldman HM. Central myxoma of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1947;33:B532–40. doi: 10.1016/0096-6347(47)90315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peltola J, Magnusson B, Happonen RP, Borrman H. Odontogenic myxoma – A radiographic study of 21 tumours. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32:298–302. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aquilino RN, Tuji FM, Eid NL, Molina OF, Joo HY, Neto FH. Odontogenic myxoma in the maxilla: A case report and characteristics on CT and MR. Oral Oncol Extra. 2006;42:133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kheir E, Stephen L, Nortje C, van Rensburg LJ, Titinchi F. The imaging characteristics of odontogenic myxoma and a comparison of three different imaging modalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adekeye EO, Avery BS, Edwards MB, Williams HK. Advanced central myxoma of the jaws in Nigeria. Clinical features, treatment and pathogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh BC, Huvos AG, Gerold FP, Miller TR. Myxoma of the jaw bones. Cancer. 1973;31:237–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197301)31:1<237::aid-cncr2820310131>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gormley MB, Mallin RE, Solomon M, Jarrett W, Bromberg B. Odontogenic myxofibroma: report of two cases. J Oral Surg. 1975;33:356–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adebayo ET, Fomete B, Ajike SO. Spontaneous bone regeneration following mandibular resection for odontogenic myxoma. Ann Afr Med. 2012;11:182–5. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.96882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adekeye EO. Rapid bone regeneration subsequent to subtotal mandibulectomy. Report of an unusual case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:521–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]