Abstract

Objective

: Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) has a high prevalence and carries significant cardiovascular risks. It is important to study new therapeutic approaches to this disease. Positional therapy might be beneficial in reducing the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). Imaging methods have been employed in order to facilitate the evaluation of the airways of OSAS patients and can be used in order to determine the effectiveness of certain treatments. This study was aimed at determining the influence that upper airway volume, as measured by cervical CT, has in patients diagnosed with OSAS.

Methods

: This was a quantitative, observational, cross-sectional study. We evaluated 10 patients who had been diagnosed with OSAS by polysomnography and on the basis of the clinical evaluation. All of the patients underwent conventional cervical CT in the supine position. Scans were obtained with the head of the patient in two positions (neutral and at a 44° upward inclination), and the upper airway volume was compared between the two.

Results

: The mean age, BMI, and neck circumference were 48.9 ± 14.4 years, 30.5 ± 3.5 kg/m2, and 40.3 ± 3.4 cm, respectively. The mean AHI was 13.7 ± 10.6 events/h (range, 6.0-41.6 events/h). The OSAS was classified as mild, moderate, and severe in 70%, 20%, and 10% of the patients, respectively. The mean upper airway volume was 7.9 cm3 greater when the head was at a 44° upward inclination than when it was in the neutral position, and that difference (17.5 ± 11.0%) was statistically significant (p = 0.002).

Conclusions

: Elevating the head appears to result in a significant increase in the caliber of the upper airways in OSAS patients.

Keywords: Sleep apnea, obstructive/prevention and control; Sleep apnea, obstructive/therapy; Tomography

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is an anatomical and functional disorder in which the chief event is the recurrent narrowing or collapse of the upper airway walls during sleep. Various factors, such as excess neck fat, high BMI, sleeping in the supine position, gravitational effects, craniofacial anomalies, pharyngeal muscle flaccidity, increased tongue volume, and enlarged palatine tonsils, can trigger or worsen the disease.( 1 )

The definition of OSAS includes recurrent episodes of complete or partial upper airway obstruction (apnea and hypopnea, respectively), with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) > 5 events/h, as determined by polysomnography, together with symptoms such as excessive daytime sleepiness. Those respiratory events, in most cases, result in decreased oxyhemoglobin saturation and in arousals (brief awakenings lasting < 15 s, characterized by the intrusion of a faster rhythm in the electroencephalogram).( 2 )

A recent study showed that the prevalence of OSAS in the population of the city of São Paulo, Brazil, is 32.8%.( 3 ) Given that OSAS results in numerous cardiovascular and metabolic complications, further study on new therapeutic techniques is warranted.( 4 - 6 ) Imaging methods have been of assistance in airway assessment in OSAS patients and can be used for comparative volumetric analysis before and after intervention.( 7 , 8 )

The most well-established treatments for OSAS are the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and the use of oral appliances. Surgery, nasal treatment, speech therapy, weight loss, and positional intervention can have clinical benefits.( 6 ) Although there have been studies showing that maintaining a lateral position reduces the AHI, there have been few studies evaluating head elevation as a therapeutic intervention.( 9 , 10 ) Therefore, a study on postural intervention is warranted in order to evaluate the influence of head elevation in patients previously diagnosed with OSAS on the basis of determination of upper airway volumes by cervical CT.

METHODS

This was an observational cross-sectional study. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade do Extremo Sul Catarinense, in the city of Criciúma, Brazil (Protocol no. 381.168/2013), and all of the patients gave written informed consent.

Between July and December of 2013, we studied ten consecutive patients (> 18 years of age) who had been diagnosed with OSAS by polysomnography (Alice 5 Diagnostic Sleep System; Phillips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA), with an AHI > 5 events/h, accompanied by symptoms (excessive daytime sleepiness, nonrestorative sleep, or fatigue), and were treated at the Criciúma Outpatient Clinic for Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine. The exclusion criteria were presenting with decompensated underlying disease (e.g., decompensated heart failure or uncontrolled asthma), weighing more than 120 kg (which exceeds the CT scanner limit), and measuring more than 64 cm from shoulder to shoulder (a width greater than the internal diameter of the CT scanner). The ten patients analyzed had not previously undergone any treatment for OSAS and were therefore treatment-naive. One patient weighed 125 kg and could not undergo CT. That patient was therefore excluded from the study.

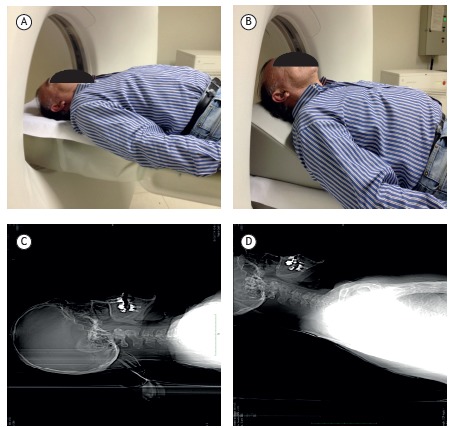

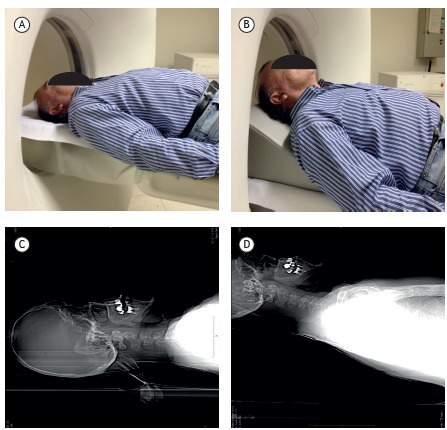

Within one week after enrolling in the study, each patient underwent cervical CT without the use of intravenous contrast. All CT images were acquired on a multislice CT scanner (Brightspeed; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) in the traditional manner. Subsequently, we positioned a 44° wedge (dimensions: 45.5 cm in its longest side × 43.3 cm × 18.5 cm) on the CT scanner table. Each patient lay, head supported on the wedge, on a line traced on its longest side, and additional cervical CT slices were obtained with a total radiation dose of less than 10 mSv. The 44° head elevation was calculated to allow the wedge to provide maximum head and neck elevation, while still allowing passage through the CT scanner gantry (height, 70 cm). The images were acquired with the patient in the supine position with the skull positioned neutrally in relation to the neck, with and without the use of the wedge. Examples of the patient positioning on the CT scanner table, with and without the 44° head elevation, as well as CT images acquired at those positions, are shown in Figure 1. The CT images acquired with and without the wedge were compared, and the pharyngeal airspace was evaluated, using three-dimensional reconstructions, between the hard palate and the base of the epiglottis in order to determine the amount of volume in cm3. On the workstation, the volume of air within the passage extending from the hard palate to the base of the epiglottis was calculated with a volume rendering program (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Linear measurements were not used, because of the possibility of multi-directional variance in airspace shape as a result of the change in the angle of the head, depending on patient biotype. Throughout the CT analysis, the subjects evaluated were awake and remained in a neutral position, avoiding extension or flexion of the neck.

Figure 1. Patient without head elevation (neutral position; in A) and with head elevation by a 44° wedge (in B). CT scans obtained with the head in the neutral position (in C) and elevated by 44° (in D).

Body weight classification based on BMI (in kg/m2) was as follows: normal weight (18.5-24.9); overweight (25.0-29.9); class I obesity (30.0-34.9); class II obesity (35.0-39.9); and class III obesity (≥ 40.0).

The criteria used in order to classify OSAS, as well as the parameters used in order to score respiratory events and arousals on polysomnography, were in accordance with those recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.( 11 , 12 )

The study data were tabulated on spreadsheets created using the IBM SPSS Statistics software package, version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All statistical tests were performed with a significance level of α = 0.05 and a confidence interval of 95%.

Numerical variables were expressed as means and standard deviations or as medians and interquartile ranges. Quantitative and qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. To analyze upper airway volume with and without head elevation, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test followed by the Student's t-test for paired samples. The variables BMI, neck circumference, and AHI were tested for correlation with the increase in upper airway volume, in percentage and absolute values (cm3), by using the Shapiro-Wilk test followed by Spearman's correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

The mean age of the patients was 48.90 ± 14.37 years (range, 27-65 years), and six patients (60%) were female. The mean BMI was 30.51 ± 3.52 kg/m2, and the mean neck circumference was 40.35 ± 3.40 cm. With regard to body weight, four participants were classified as being overweight, four as having class I obesity, one as having class II obesity, and one as having normal weight. The mean AHI was 13.7 ± 10.6 events/h (range, 6.0-41.6 events/h). Therefore, the polysomnographic diagnosis (AHI) was mild OSAS in seven patients (70%); moderate OSAS in two (20%); and severe OSAS in one (10%). A descriptive profile of the quantitative variables in the sample is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample.

| Variable | Mean ± SD or median (IQR) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 48.90 ± 14.37 | 27.00 | 65.00 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.51 ± 3.52 | 24.68 | 35.75 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 40.35 ± 3.40 | 35.50 | 46.00 |

| AHI, events/h | 13.75 ± 10.60 | 6.00 | 41.60 |

| Upper airway volume without head elevation, cm3 | 40.35 ± 16.43 | 14.40 | 75.85 |

| Upper airway volume with head elevation, cm3 | 48.31 ± 16.21 | 18.66 | 79.94 |

| Increase in volume, % | 17.49 ± 10.99 | 5.10 | 36.96 |

| Increase in volume, cm3 | 5.45 (4.09-11.15) | 3.46 | 18.89 |

IQR: interquartile range; and AHI: apnea-hypopnea index.

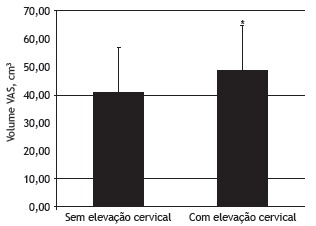

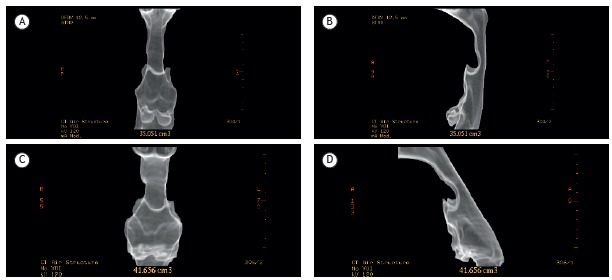

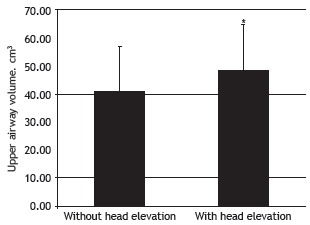

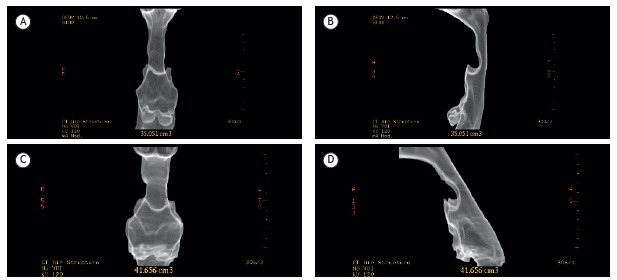

In the CT analysis, the mean upper airway volume was 40.35 ± 16.43 cm3 without head elevation and 48.31 ± 16.21 cm3 with head elevation (Figure 2). The change in mean upper airway volume was 7.9 cm3, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.002) in caliber at a 44° head elevation. The mean percentage increase in upper airway volume, as determined by CT analysis, was 17.49 ± 10.99%. The median (interquartile range) increase in upper airway volume was 5.45 (4.09-11.15) cm3. As an example, we show the case of one of the patients in the study, with an increase of 6.6 cm3 (15.8%) in upper airway volume, as determined by cervical CT (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Upper airway volume, as measured by cervical CT, before and after the use of a wedge to elevate the head. *p = 0.02.

Figure 3. Cervical CT for determining upper airway volume-in the neutral position (without head elevation): anterior view (in A) and lateral view (in B); and with the head elevated by 44° with a wedge: anterior view (in C) and lateral view (in D). Volume was measured from the hard palate to the base of the epiglottis.

There was no significant correlation between the increase in upper airway volume and the hypopnea index (tau-b = −0.138; p = 0.586). Nor were there significant correlations between the increase in upper airway volume and the variables BMI, neck circumference, or AHI (Table 2). In addition, there were no statistically significant correlations between the various BMI categories and the severity of OSAS.

Table 2. Analysis of correlation between numerical variables and the increase in upper airway volume.

| Variable | Increase in volume, cm³ | p | Increase in volume, % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m² | −0.030 | 0.934 | 0.079 | 0.829 |

| Neck circumference, cm | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.006 | 0.987 |

| AHI, events/h | −0.248 | 0.489 | −0.285 | 0.425 |

| HI, events/h | 0.782 | 0.001 | −0.138 | 0.586 |

AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; and HI: hypopnea index.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed a mean increase of 7.9 cm3 in upper airway volume, as measured by CT, at a 44° head elevation. A study conducted in Taiwan, involving CT evaluation of 16 patients, showed that upper airway volume increased by 6.1 cm3 after maxillomandibular advancement surgery.( 8 ) In the literature, there are conflicting data regarding the percentage change in upper airway caliber after surgery (preoperative and postoperative comparative volumetric analysis).( 13 - 16 ) For example, one study reported a 26% increase in total volume,( 15 ) whereas another reported a 2% reduction in total volume. ( 13 ) In our assessment using CT imaging, upper airway volume was 17.49% greater with head elevation than without. In 18 patients undergoing MRI, Sutherland et al.( 17 ) compared the upper airway structure at baseline (i.e., without an oral appliance), with a mandibular advancement splint, and with a tongue stabilizing device, reporting mean volumes of 13.8 ± 1.0 cm3, 14.3 ± 1.1 cm3, 17.14 ± 1.6 cm3, respectively. Therefore, the volumetric improvement varied only from 0.50 cm3 to 2.84 cm3, depending on the type of appliance employed. In 10 patients undergoing MRI, Schwab et al.( 18 ) showed that the mean airway volume was 11.7 mm3 at baseline (i.e., at 0 cmH2O of CPAP) and progressively increased to 13.2 mm3, 16.8 mm3, and 20.5 mm3, with CPAP increases of 5 cmH2O, 10 cmH2O, and 15 cmH2O, respectively. However, another study showed a modest increase in upper airway volume, as measured by MRI, with the use of CPAP( 19 )-upper airway volume was 9.3 mL and 11.8 mL at 0 and 9 cmH2O of CPAP, respectively, an increase of 2.5 mL (p < 0.05).

Elevating the head of the bed is an old postural intervention, widely used to assist in the treatment of subjects with gastroesophageal reflux, that is based on the principle of reducing acid exposure time and changing intra-abdominal pressure.( 20 , 21 ) This postural intervention yields good results in pH measurements and leads to an improvement in symptoms.( 22 , 23 ) However, few studies have examined the effect of head or head-and-shoulder elevation on OSAS.( 9 , 10 , 24 , 25 )

McEvoy et al.( 10 ) studied 13 male patients during the same night and reported a reduction in AHI from 49 ± 5 events/h to 20 ± 7 events/h when patients changed from the supine position to a sitting position at a 60° angle. Skinner et al.( 24 ) studied 14 subjects in the supine position (no elevation), comparing it with head-and-shoulder elevation (with a shoulder-head elevation pillow), and reported a 22% reduction in AHI. Studies have shown that upper airway closing pressure is reduced when the individual is moved from the supine position (no elevation) to an inclined position (30° head elevation),( 25 ) as well as when the individual is moved from the supine position to a sitting position.( 26 ) In a study of 17 patients undergoing polysomnography, Souza et al.( 9 ) evaluated AHIs at baseline (i.e., during standard polysomnography) and after elevating the head of the bed 15 cm, reporting a significant reduction in the mean AHI (20 ± 14 events/h vs. 15 ± 14 events/h; p = 0.0003). It has been hypothesized that head elevation contributes to upper airway clearance, prevents rostral fluid shift,( 27 ) and averts tongue collapse,( 28 ) reducing upper airway resistance,( 10 ) changing upper airway critical pressure,( 29 ) affecting gravitational effects,( 30 ) and altering neuromuscular activity.( 31 )

In our study, the severity of OSAS did not correlate with BMI, which differs from the findings of some epidemiological studies in the literature, such as a study involving 300 patients treated at a sleep clinic in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil.( 32 ) Nor did neck circumference correlate with OSAS severity. These differences are probably related to the small number of patients in our study.

Although our study is limited by its small sample size, studies that have employed imaging for assessment of upper airway volume after some treatment for OSAS have evaluated a similar number of patients.( 8 , 9 , 11 , 13 ) Another limitation was that the CT study was not performed with the patient asleep under sedation or anesthesia, but rather with the patient awake, which could have affected muscle tone. Litman et al.( 33 ) showed that propofol-sedated children had higher upper airway volumes in the lateral position than in the supine position; however, the mean increase was 2.7 mL. Other limiting factors of the present study are the lack of a control group, the fact that most of our patients had mild OSAS, and the predominance of females (60%), which is uncharacteristic of OSAS studies, in which males typically predominate. In addition, the fact that we did not take into consideration the anatomical differences between the upper airways of males and those of females constitutes a limiting factor.

We conclude that, in our sample of patients with OSAS, there was an increase in upper airway volume, as measured by cervical CT, at a 44° head elevation. Further studies involving a larger number of patients are needed in order to assess the change in upper airway volume resulting from head elevation and the true clinical benefit of this intervention.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Curso de Medicina, Universidade do Extremo Sul Catarinense - UNESC - Criciúma (SC) Brasil.

Financial support: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redline S, Budhiraja R, Kapur V, Marcus CL, Mateika JH, Mehra R. The scoring of respiratory events in sleep: reliability and validity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(2):169–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tufik S, Santos-Silva R, Taddei JA, Bittencourt LR. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep Med. 2010;11(5):441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan AG, Perlikowski SM, Mente A, Tisler A, Tkacova R, Niroumand M. High prevalence of unrecognized sleep apnoea in drug-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2001;19(12):2271–2277. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhama JK, Spagnolo S, Alexander EP, Greenberg M, Trachiotis GD. Coronary revascularization in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Heart Surg Forum. 2006;9(6):E813–E817. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20061072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver TE, Calik MW, Farabi SS, Fink AM, Galang-Boquiren MT, Kapella MC. Innovative treatments for adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Sci Sleep. 2014;6:137–147. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S46818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterfield KJ, Marks PL, McLean L, Newton J. Linear and volumetric airway changes after maxillomandibular advancement for obstructive sleep apnea. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(6):1133–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh YJ, Liao YF, Chen NH, Chen YR. Changes in the calibre of the upper airway and the surrounding structures after maxillomandibular advancement for obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(5):445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souza FF, Souza A, Filho, Lorenzi-Filho G. The influence of bedhead elevation on patients with obstructive sleep apnea [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A2732–A2732. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2011.183.1_meetingabstracts.a2732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEvoy RD, Sharp DJ, Thornton AT. The effects of posture on obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133(4):662–666. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & coding manual. 2. IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry RB, Brooks, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Marcus CL, Vaughn BV. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Version 2.0. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotecha BT, Hall AC. Role of surgery in adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(5):405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Chun YS, Kang N, Kim M. Volumetric changes in the upper airway after bimaxillary surgery for skeletal class III malocclusions: a case series study using 3-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(12):2867–2875. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faria AC, da SN, Silva-Junior, Garcia LV, dos Santos AC, Fernandes MR, de Mello-Filho FV. Volumetric analysis of the pharynx in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treated with maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) Sleep Breath. 2013;17(1):395–401. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sittitavornwong S, Waite PD, Shih AM, Cheng GC, Koomullil R, Ito Y. Computational fluid dynamic analysis of the posterior airway space after maxillomandibular advancement for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(8):1397–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland K, Deane SA, Chan AS, Schwab RJ, Ng AT, Darendeliler MA. Comparative effects of two oral appliances on upper airway structure in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2011;34(4):469–477. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwab RJ, Pack AI, Gupta KB, Metzger LJ, Oh E, Getsy JE. Upper airway and soft tissue structural changes induced by CPAP in normal subjects. Pt 1Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4):1106–1116. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan CF, Lowe AA, Li D, Fleetham JA. Magnetic resonance imaging of the upper airway in obstructive sleep apnea before and after chronic nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(4):939–944. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan BA, Sodhi JS, Zargar SA, Javid G, Yattoo GN, Shah A. Effect of bed head elevation during sleep in symptomatic patients of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(6):1078–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitchin LI, Castell DO. Rationale and efficacy of conservative therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(3):448–454. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400030018004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanciu C, Bennett JR. Effects of posture on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Digestion. 1977;15(2):104–109. doi: 10.1159/000197991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):965–971. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skinner MA, Kingshott RN, Jones DR, Homan SD, Taylor DR. Elevated posture for the management of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2004;8(4):193–200. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-860896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neill AM, Angus SM, Sajkov D, McEvoy RD. Effects of sleep posture on upper airway stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):199–204. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tagaito Y, Isono S, Tanaka A, Ishikawa T, Nishino T. Sitting posture decreases collapsibility of the passive pharynx in anesthetized paralyzed patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(4):812–818. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f1b834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redolfi S, Yumino D, Ruttanaumpawan P, Yau B, Su MC, Lam J. Relationship between overnight rostral fluid shift and Obstructive Sleep Apnea in nonobese men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(3):241–246. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1076OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horner RL. The tongue and its control by sleep state-dependent modulators. Arch Ital Biol. 2011;149(4):406–425. doi: 10.4449/aib.v149i4.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi M, Ayuse T, Hoshino Y, Kurata S, Moromugi S, Schneider H. Effect of head elevation on passive upper airway collapsibility in normal subjects during propofol anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(2):273–281. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318223ba6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oksenberg A, Silverberg DS. The effect of body posture on sleep-related breathing disorders: facts and therapeutic implications. Sleep Med Rev. 1998;2(3):139–162. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(98)90018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malhotra A, Trinder J, Fogel R, Stanchina M, Patel SR, Schory K. Postural effects on pharyngeal protective reflex mechanisms. Sleep. 2004;27(6):1105–1112. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knorst MM, Souza FJ, Martinez D. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: association with gender, obesity and sleepiness-related factors J Bras. Pneumol. 2008;34(7):490–496. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008000700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litman RS, Wake N, Chan LM, McDonough JM, Sin S, Mahboubi S. Effect of lateral positioning on upper airway size and morphology in sedated children. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(3):484–488. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]