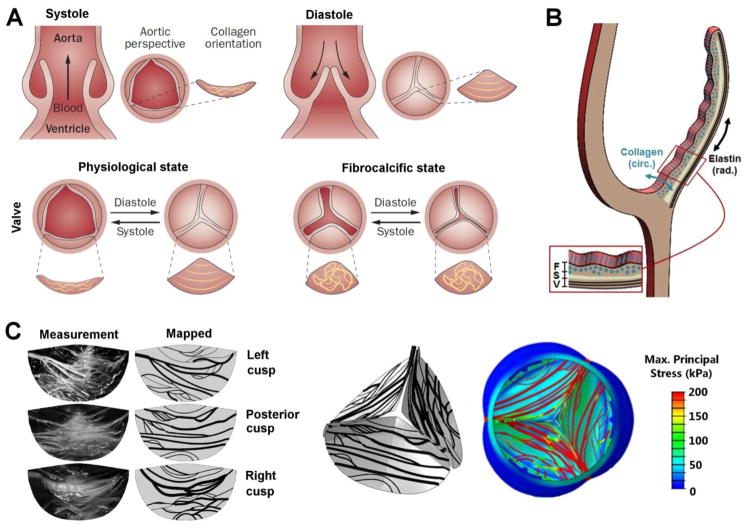

Fig. 4.

Structure of the aortic valve in health and disease. (A) Schematic description of a healthy aortic valve. Systolic contraction of the left ventricle forces the aortic valve leaflets to open, allowing blood to enter the aorta. The reversed pressure gradient, created when the heart rests in diastole, causes the aortic valve leaflets to close, preventing retrograde blood flow into the heart. Circumferential collagen alignment allows the leaflets to stretch in the radial direction while providing the tensile strength required to prevent leaflet prolapse. Loss of ECM organization associated with fibrocalcific diseased state. Reprinted from[148] with permission from Macmillan Publishers Limited; (B) Schematic cross-sectional view of a valve leaflet showing fibrosa, F, spongiosa, S, and ventricularis, V, layers. Circumferential collagen alignment in the fibrosa and radial elastin alignment in the ventricularis are indicated; (C) Left: Stretched cusps and the mapped collagen fiber network. Right: A 3D view from the aortic side of collagen fiber maps and associated maximum principal stress contours plotted on the deformed structure during diastole. Reprinted from[144] with permission from ASME.