Abstract

A thermophilic, heterotrophic and facultatively anaerobic bacterium designated strain D7XPN1 was isolated from Baku BakuKing™, a commercial food-waste degrading bioreactor (composter). The strain grew optimally at 45 °C (growth range between 24 and 50 °C) and pH 7 (growth pH range between pH 5 and 9) in Luria Broth supplemented with 0.3 % glucose. Strain D7XPN1 tolerated up to 7 % NaCl and showed amylolytic and xylanolytic activities. 16S rRNA gene analysis placed strain D7XPN1 in the cluster represented by Bacillus subtilis and the genome analysis of the 4.1 Mb genome sequence determined using RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) indicated a total of 5116 genomic features were present of which 2320 features could be grouped into several subsystem categories. Of these, 615 features were related to carbohydrate metabolism which included a range of enzymes with potential in the biodegradation of food wastes, a property consistent with the ecological habitat of the isolate. ANIb (Average Nucleotide Identity based on BLAST) analysis with 49 Bacillus subtilis genomes indicated that it was distantly related to the three currently taxonomically validated B. subtilis subspecies namely B. subtilis subsp. subtilis (95.6 %), B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii (93 %) and B. subtilis subsp. inaquosorum (92 %) and based on our current knowledge warranted that it be included as a separate cluster together with strain JS which it was closely related (98.69 %). The close relationship of strains D7XPN1 and JS is also supported from our results from electronic DNA–DNA Hybridization (e-DDH) studies. Furthermore, our additional in-depth phylogenomic analyses using three different datasets unequivocally supported the creation of a fourth B. subtilis subspecies to include strains D7XPN1 and JS for which we propose strain D7XPN1T (=KCTC 33554T, JCM 30051T) as the type strain, and designate it as B. subtilis subsp. stecoris.

Keywords: Moderate thermophile, Bacillus subtilis subspecies, Phylogenomics, Bacillus subtilis subspecies stecoris

Introduction

The members of the genus Bacillus comprise the low G+C containing Gram-positive bacteria and belong to the family Bacillaceae, order Bacillales, class Bacilli, phylum Firmicutes, domain Bacteria. They grow in a diverse range of habitats and include species that grow at extreme temperatures, salinities and pH. The phenotypic traits and physiologies of members of the genus Bacillus are as dynamic and wide ranging as their habitats and include species that grow as heterotrophs, autotrophs, in the presence or absence of oxygen and yet others grow in the presence of alternate electron acceptors such as iron, arsenate (Kanso et al. 2002). The extreme metabolic diversity, their non-pathogenic nature and the ease of isolating, handling and maintainance has opened them to biotechnological exploitation and in particular for use in agriculture, e.g. crop protection (Gao et al. 2015; Hussein et al. 2015; Ji et al. 2008). 16S rRNA-based taxonomy is routinely used to build taxonomic relationship amongst members of the domain Bacteria but it is well established that this technique fails to resolve closely related Bacillus species in which evolutionary divergence is limited. Given the lack of discriminatory power of 16S rRNA genes, a polyphasic taxonomic approach which combines 16S rRNA sequence analysis with phenotypic traits and DNA–DNA homology has been recommended to improve resolution. Examples of such an approach include the members of the Bacillus cereus sensu lato group which currently comprises of 6 species (B. cereus, B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis, B. mycoides and B. psedomycoides and B. weihenstephanensis (Zwick et al. 2012) and the B. subtilis group which comprises of 3 species B. subtilis, B. vallismortis and B. mojavensis (Roberts et al. 1994, 1996). However, the topology of polyphasic trees is not always robust and can differ from the 16S rRNA based trees and therefore delineating species and strain boundaries using a polyphasic approach can be confusing. With the advent of the high throughput cost effective Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, estimation of overall similarity of microbial genomes by Genome-to-Genome Distance Comparison (GGDC), Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and genome phylogeny are being considered not only for delineating closely related species but also for taxonomic assignment of new isolates (Maughan and Van der Auwera 2011; Yi et al. 2014). Here we describe the construction of a molecular phylogenetic framework for Bacillus subtilis using genome sequences and its application to strain D7XPN1, an isolate from Baku Baku King™, a commercial food-waste degrading bioreactor (Adelskov 2013; Adelskov and Patel 2014).

Materials and methods

Bioreactor operation and sample collection

Biodegradation of food-wastes was carried out using Baku Baku King™ (model: M.I.G.0100), a food waste bioreactor. The biodegradation process was started in the bioreactor (day 0) by mixing 50 kg of municipal food waste sourced from a local hotel (Novotel Hotel, Gold Coast) with 200 kg of methyl bromide treated Japanese Larch wood chips and a microbial starter seed culture. The starter microbial seed culture was prepared by mixing 10 kg of leaf litter (collected from the Forest reserve located at Griffith University Nathan campus, Brisbane, Australia), with nutrients (sugar, honey, milk, meat, fish) followed by incubation for one week at room temperature (25–30 °C) before inoculation into the bioreactor. The bioreactor was subsequently fed 50 kg of municipal food waste per day sourced from the same hotel over a 49 day period. Samples (approximately 500 g) were collected from the bioreactor every 7–10 days of its normal operation cycle of 49 days including day 0 (the day of inoculation of the bioreactor with a starter seed culture). In total, seven samples were collected (days 0, 1, 7, 17, 21, 29 and 49). The temperature and aeration in the bioreactor was controlled by the inbuilt bioreactor’s electronic system.

Enrichment, isolation and phylogeny

1 g of bioreactor samples was resuspended in 10 ml sterile dH2O the solution shaken for 2 min and the debris allowed to settled for 5 min. 200 µl of settled suspension was spread on dTSA agar medium [dTSA consisted of 0.1 % (w/v) Tryptic Soy Broth, 1.5 % (w/v) bacteriological agar, pH 7.2]. The temperature of the bioreactor during most of the operation period was between 40 and 45 °C and hence the plates were incubated at 45 °C until colonies developed. Single well-isolated colonies that appeared morphologically distinct were picked and resuspended in sterile dH2O and a loopful streaked onto dTSA agar plates and incubated at 45 °C until colonies developed. This procedure was repeated several times before the isolates were considered to be pure. 28 pure cultures (Table 1) were obtained using this process and were stored at 4 °C and −20 °C. All isolates were routinely cultured using 0.1 % (w/v) (dilute) Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), pH 7.2.

Table 1.

List of strains isolated from the waste-food degrading bioreactor, Baku Baku™

| Day | Isolate | Colony morphologya | Enzyme activityb | Closest phylogenetic memberc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylanase | Amylase | ||||

| 0 | BXP1 | Irregular, white, 2–3 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. 168 |

| 0 | BXP7 | Slighly irregular, mucoid, white, 2–3 mm | – | + | Bacillus vallismortis str. DSM 11031 |

| 1 | BXP11 | Circular, white, 1 mm | + | + | Paenibacillus cookii str. LMG 18419 |

| 1 | BXP12 | Circular, irregular margin, 1 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 1 | BXP13 | Circular, white, 1–2 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. 168 |

| 7 | D7XPN1 | Circular, irregular margin, white, 1 mm | + | + | Bacillus subtilis str. 168 |

| 16 | D16IS1 | Irregular, filamentous margin, white, 5–6 mm | – | + | Bacillus aerius str. 24 K |

| 16 | D16IS2 | Circular, mucoid, white, 1.5–2 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 16 | D16IS3 | Rhizoid, white, 4–6 mm | – | + | Bacillus licheniformis str. ATCC 14580 |

| 16 | D16IS5 | Filamentous, translucent | – | – | Kurthia gibsonii str. NBRC 15534 |

| 16 | P1XP2 | Circular, mucoid, white, 0.7 mm | + | + | Paenibacillus cookii str. LMG 18419 |

| 16 | P1XP3 | Irregular, white, 1–3 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 16 | P1XP5 | Circular,mucoid, white, 0.8 mm | + | + | Paenibacillus cookii str. LMG 18419 |

| 21 | D21IS1 | Circular, mucoid, white, 1–1.2 mm | – | + | Paenibacillus ehimensis str. KCTC 3748 |

| 21 | D21IS2 | Irregular, slighly opague white, 2 mm | – | + | Bacillus licheniformis str. ATCC 14580 |

| 21 | D21IS3 | Rhizoid, white, 3 mm | – | + | Bacillus licheniformis str. ATCC 14580 |

| 21 | D21IS4 | Circular, irregular margin, white 3–4 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 29 | D29IS4 | Circular, mucoid, white, 1 mm | + | + | Paenibacillus cookii str. LMG 18419 |

| 29 | D29IS5 | Circular, irregular margin, white, 2–3 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 29 | D29IS6 | Irregular, slightly opaque, white, 4–5 mm | + | + | Bacillus licheniformis str. ATCC 14580 |

| 35 | D35IS1 | Irregular, filamentous margin, white, 6 mm | – | + | Bacillus aerius str. 24 K |

| 35 | D35IS3 | Irregular, white, 1.2 mm | – | – | Brevibacillus agri str. DSM 6348 |

| 35 | D35IS5 | Filamentous, translucent, spreading | – | – | Bacillus badius str. 110 |

| 42 | D42IS3 | Circular, mucoid, white, 1.2 mm | + | + | Paenibacillus cookii str. LMG 18419 |

| 49 | D49IS3 | Irregular, white, 2–4 mm | – | + | Bacillus subtilis str. DSM 10 |

| 49 | D49IS4 | Circular, filamentous margin, white, 3–4 mm | – | + | Bacillus licheniformis str. ATCC 14580 |

| 49 | D49IS5 | Circular, slightly translucent, mucoid, 0.5 mm | – | – | Aneurinibacillus migulanus str. B0270 |

aThe strains were isolated on 0.1 % (dilute) Tryptic Soy Agar (dTSA) medium and colony morphology noted after 48 h incubation at 45 °C

bXylanase and amylase activities were determined as described in “Materials methods” Section

cThe closest phylogenetic match was determined by BLAST analysis of the 16S rRNA sequences of the isolates against the NCBI 16S ribosomal RNA (Bacteria and Archaea) database

The 28 isolates were cultured in TSB (pH 7.0) at 45 °C for 18 h, the cells centrifuged and the DNA from the pelleted cells purified using a modification of Marmur’s method as described by Ogg and Patel (2009). In brief, bacterial cells were resuspended in a buffered solution (50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.8) and treated with 0.8 mg/ml lysozyme, 0.3 mg/ml Achromopeptidase and 0.1 mg/ml RNAse A and subsequently lysed by adding 0.12 mg/ml Proteinase K and 6 mg/ml sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) to the suspension. The DNA from the lysate was purified using phenol:chloroform extraction. Purified DNA quality was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA concentration determined fluorometrically using a Qubit™ dsDNA HS assay kit as described by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, USA). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified from the DNA of the isolate by PCR using the universal forward primer Fd1 (AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and reverse primer Rd1 (AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC) that bind to the 8–27 and 1512–1493 base pair positions of E. coli numbering scheme according to Winkler and Woese (1991). Reactions of 50 µl volume consisted of: 0.2 mMdNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Fd1, 1 mM Rd1, 0.5–5 ng of DNA template, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Mango Taq) and provided reaction buffer. PCR proceeded using a Corbett Research FTS-1 Thermal sequencer with the following cycle program: cycle 1; 2 min 95 °C; 1 min 50 °C; 2 min 70 °C, cycle 2–32; 55 s 94 °C, 1 min 50 °C, 2 min 72 °C. The reaction amplicon was purified by either SureClean™ or Gel extraction (QIAGEN) following manufacturer’s instructions. The purified amplicons were sequenced on an ABI 3730xl 96-capillary sequencer using Fd1 and Rd1 primers at AGRF (Australian Genetics Research Facility). 16S rRNA gene sequence manipulation and phylogenetic analysis was performed as described previously (Redburn and Patel 1994).

All isolates were screened for the presence of amylase activity by inoculating a loopful of culture onto dTSA agar medium supplemented with 1 % soluble potato starch (Chem Supply, Australia) and incubation at 45 °C until colonies developed. The plates were flooded with Gram’s Iodine solution and a positive reaction for amylase production recorded for isolates when there was a zone of clearance around colonies against a red–purple background. Isolates were screened for xylanase activity by streaking X-xyl Agar plates followed by incubation at 45 °C. X-xyl Agar plates contained (g−L distilled water): Tryptic Soy Broth (Oxoid, USA) 1 g, xylan from birchwood (Sigma, USA) 3 g, Bacteriological Agar (Oxoid, USA) 15 g, X-β-D-xyloside (Gold Biotech, USA) 0.2 g, pH 7.2 and incubated at 45 °C. Xylanase production was recorded as positive when colonies showed a blue color.

One of the isolates designated D7XPN1, which produced a xylanase and amylase, was selected for further studies and is described in more detail in this paper.

Characterization of strain D7XPN1

Temperature, pH and salinity growth studies were conducted in 18 mm glass culture tubes containing 15 ml of modified Luria Bertoni Broth (mLBB). mLBB contained per litre Luria Bertoni Broth (Oxoid, USA) 25 g, d-Glucose anhydrous (Lab Supply, Australia) 3 g. For temperature studies, mLLB was inoculated with 0.2 ml of an overnight culture and incubated in water baths maintained at 37, 45, 50, 60, 70 °C and incubated for 48 h. For pH studies, the pH of mLBB was changed to the desired pH (pH range of 4.0–10) by addition of 1 M HCl or 1 M NaOH, inoculated with 0.2 ml of an overnight culture and incubated in water baths maintained at 45 °C. For salinity studies, appropriate amounts of NaCl was weighed and added to mLBB medium to achieve the desired concentration of salinity (3–7 %), inoculated with 0.2 ml of an overnight culture and incubated in a water bath maintained at 45 °C for 48 h. Following incubation, growth was determined by inserting the glass culture tubes directly into a modified cuvette holder of a Novaspec LKB spectrophotometer and the absorbance measured at 600 nm. Anaerobic growth was tested in Trypticase, Yeast Extract, Glucose (TYEG) medium as described previously (Ogg and Patel 2009).

Dataset and genome sequencing

Unless indicated otherwise, all computational analysis was performed using a 16 CPU Dell workstation with 64 gigabytes RAM and an Intel® Xeon(R) CPU X5570 @ 2.93 GHz × 8 chipset running Ubuntu 12.04 and the Australian Government Information Technology Infrastructure Facilities accessed under the National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources (NeCTAR) program.

Complete and draft Whole Genome Sequences (WGS) for all strains that were identified in GenBank microbial genome database as Bacillus subtilis, B. amyloliquefaciens and B. atrophaeus were downloaded from the NCBI ftp server ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/genbank/bacteria (release 204) (Table 2). Unless indicated otherwise, sequence contigs from all GenBank files were extracted and converted to fasta format (Vesth et al. 2013) and any plasmid sequences accompanying the genome data (B. subtilis subsp. natto str. BEST195, B. subtilis subsp. str. NCIB 3610 and B. subtilis subsp. subtilis str. B7-s) were removed before use in comparative genomic studies.

Table 2.

Bacillus subtilis strains used in determining the Overall Genome Relatedness Indices (OGRI) using Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculations (GGDC) and Average Nucleotide Identity by Blast (ANIb) and phylogenomics

| No. | B. subtilis strain | Accession Number | Sample source | Total nucleotide (bp) | No. of Contigs | Largest Contig size (%) | N25 | N50 | N75 | G+C mol % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1. Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis | ||||||||||

| 1 | Bacillus subtilis subsp subtilis str. JH642 substr. AG174 | CP007800 | Not known | 4,188,369 | 1 | 100 | 4,188,369 | 4,188,369 | 4,188,369 | 43.00 |

| 2 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. AG1839 | CP008698 | Not known | 4,193,640 | 1 | 100 | 4,193,640 | 4,193,640 | 4,193,640 | 43.48 |

| 3 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. JH642* | CM000489 | Laboratory strain | 4,187,615 | 1 | 100 | 4,187,615 | 4,187,615 | 4,187,615 | 43.49 |

| 4 | Bacillus subtilis str. PY79 | CP006881 | Laboratory strain | 4,033,459 | 1 | 100 | 4,033,459 | 4,033,459 | 4,033,459 | 43.83 |

| 5 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. QB928* | CP003783 | Laboratory strain | 4,146,839 | 1 | 100 | 4,146,839 | 4,146,839 | 4,146,839 | 43.61 |

| 6 | Bacillus subtilis str. E72 | JNCN01000000 | Laboratory strain | 4,168,037 | 35 | 28.242 | 1,177,131 | 1,017,254 | 487,713 | 43.39 |

| 7 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168* | AL009126 | Not known | 4,215,606 | 1 | 100 | 4,215,606 | 4,215,606 | 4,215,606 | 43.51 |

| 8 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. SMY* | CM000490 | Not known | 4,214,643 | 1 | 100 | 4,214,643 | 4,214,643 | 4,214,643 | 43.51 |

| 9 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. NCIB_3610 (T)* | CM000488 | Not known | 4,292,969 | 80 | 98.174 | 4,214,598 | 4,214,598 | 4,214,598 | 43.51 |

| 10 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. NDmed | JPVW01000000 | Endoscope disinfector, UK | 4,059,983 | 10 | 29.391 | 1,193,268 | 939,235 | 438,498 | 43.69 |

| 11 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. NDfood | JPVX01000000 | Dairy product, France | 4,060,577 | 12 | 26.097 | 1,059,688 | 556,411 | 438,563 | 43.69 |

| 12 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str BEST7003 | CP007800 | Not Known | 4,043,042 | 1 | 100 | 4,043,042 | 4,043,042 | 4,043,042 | |

| 13 | Bacillus subtilis str. MB73-2 | AOTY01000000 | Meadow soil, Poland | 4,170,657 | 35 | 35.757 | 1,491,311 | 1,017,190 | 926,340 | 43.43 |

| 14 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 6051-HGW | CP003329 | Not known | 4,215,610 | 1 | 100 | 4,215,610 | 4,215,610 | 4,215,610 | 43.51 |

| 15 | Bacillus subtilis str. PS216 | AQGR01000000 | Sandy soil from Sava river bank, Slovenia | 4,307,186 | 146 | 21.585 | 298,458 | 177,899 | 105,241 | 43.77 |

| 16 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. AUSI98* | JH600074 | Soil, Austria | 4,353,151 | 123 | 5.516 | 181,423 | 128,442 | 59,891 | 43.48 |

| 17 | Bacillus subtilis str. QH-1 | AZQS01000000 | Soil, China | 4,034,036 | 11 | 25.876 | 1,043,843 | 1,043,657 | 1,029,685 | 43.71 |

| 18 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. SC-8* | AGFW01000000 | Korean traditional fermented-soybean, Korea | 4,138,818 | 17 | 27.059 | 1,119,942 | 8,37,849 | 252,500 | 43.46 |

| 19 | Bacillus subtilis str. GXA-28 | JPNZ01000000 | Marine sand, China | 4,261,419 | 13 | 27.141 | 1,156,606 | 110,0410 | 1,052,768 | 43.59 |

| 20 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. OH | CP007409 | Wheat anther, USA | 4,039,155 | 1 | 100 | 4,039,155 | 4,039,155 | 4,039,155 | 43.85 |

| 21 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BSn5* | CP002468 | Amorphophallus konjac calli tissue culture | 4,093,599 | 1 | 100 | 4,093,599 | 4,093,599 | 4,093,599 | 43.85 |

| 22 | Bacillus subtilis str. KATMIRA1933 | JMEF01000000 | Yogurt- cultured beverage, USA | 4,263,792 | 125 | 5.031 | 139,190 | 90,789 | 43,123 | 43.38 |

| 23 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BSP1 | CP003695 | Not known | 4,043,754 | 1 | 100 | 4,043,754 | 4,043,754 | 4,043,754 | 43.87 |

| 24 | Bacillus subtilis str. PTS-394 | AWXG01000000 | Tomato rhizosphere soil, China | 4,005,786 | 34 | 25.38 | 1,016,662 | 471,675 | 239,700 | 43.69 |

| 25 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BEST195* | AP011541 | Natto production strain, Japan | 4,111,218 | 2 | 99.858 | 4,105,380 | 4,105,380 | 4,105,380 | 43.50 |

| 26 | Bacillus subtilis str. S1-4 | ANIP01000000 | Feathers from a poultry farm, China | 4,454,050 | 104 | 6.288 | 152,724 | 88,085 | 54,963 | 43.08 |

| 27 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. MP9 | APMW01000000 | Macrotermes natalensis, South Africa | 3,952,500 | 323 | 2.905 | 35,773 | 23,097 | 12,323 | 43.78 |

| 28 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. MP11 | APMX01000000 | Macrotermes natalensis, South Africa | 3,930,802 | 647 | 1.58 | 18,223 | 11,158 | 6272 | 43.69 |

| 29 | Bacillus subtilis str. E1 | CAUC01000000 | Identified as a plant growth promoting bacterium | 4,106,253 | 16 | 28.556 | 1,172,592 | 987,088 | 332,060 | 43.55 |

| 30 | Bacillus subtilis str. Hal1 | AMCA01000000 | River water, India | 3,979,047 | 345 | 3 | 36,650 | 22,550 | 12,343 | 43.79 |

| 31 | Bacillus subtilis str. XF-1 | CP004019 | Rhizosphere of chinese cabbage, Brassica pekinensis infected with Plasmodiophora brassicae | 4,061,186 | 1 | 100 | 4,061,186 | 4,061,186 | 4,061,186 | 43.86 |

| 32 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BAB-1 | CP004405 | Cotton rhizosphere | 4,021,944 | 1 | 100 | 4,021,944 | 4,021,944 | 4,021,944 | 43.89 |

| 33 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. RO-NN-1* | CP002906 | Soil | 4,011,949 | 1 | 100 | 4,011,949 | 4,011,949 | 4,011,949 | 43.87 |

| Cluster 2. Bacillus subtilis subsp. stecoris | ||||||||||

| 34 | Bacillus subtilis str. D7XPN1 (This study) | JHCA00000000 | Food waste bioreactor (Baku Baku), Australia | 4,079,419 | 28 | 24.943 | 1,010,461 | 504,008 | 237,557 | 43.80 |

| 35 | Bacillus sp. JS | CP003492 | Pot soil of Miscanthus, Korea | 4,120,406 | 1 | 100 | 4,120,406 | 4,120,406 | 4,120,406 | 43.93 |

| Cluster 3. Bacillus subtilis subsp. inaquosorum | ||||||||||

| 36 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. inaquosorum str. KCTC_13429 (T)* | AMXN01000000 | South Korea | 4,342,448 | 24 | 19.076 | 744,296 | 566,730 | 272,952 | 43.69 |

| 37 | Bacillus subtilis str. gtP20b* | AEHM01000000 | 608-m deep sediment, Indian Ocean | 4,205,767 | 88 | 13.052 | 284,523 | 221,307 | 70,214 | 43.99 |

| Cluster 4. Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii | ||||||||||

| 38 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. TU-B-10 (T)* | CP002905 | Soil, Tunisia | 4,207,222 | 1 | 100 | 4,207,222 | 4,207,222 | 4,207,222 | 43.82 |

| 39 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. DV1-B-1* | AFSG01000000 | Soil, Death Valley National Monument USA | 3,974,551 | 20 | 20.692 | 789,480 | 684,333 | 279,652 | 43.60 |

| 40 | Bacillus subtilis str. BSC154 | JPWY01000000 | Biological Soil Crust, USA | 4,028,151 | 19 | 18.739 | 660,959 | 634,763 | 223,155 | 43.72 |

| 41 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. W23* | CP002183 | Laboratory strain | 4,027,676 | 1 | 100 | 4,027,676 | 4,027,676 | 4,027,676 | 43.89 |

| 42 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. ATCC_6633* | ADGS01000000 | Laboratory strain | 3,978,576 | 37 | 8.234 | 269,373 | 170,545 | 122,278 | 43.82 |

| 43 | Bacillus subtilis str. BST | KN049967 | Laboratory strain | 4,043,115 | 1 | 100 | 4,043,115 | 4,043,115 | 4,043,115 | 43.93 |

| Isolates whose genomes show that they are not members of Bacillus subtilis | ||||||||||

| 44 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. niger str. PCI** | KN049968 | USAMRIID, USA | 4,154,887 | 2 | 99.845 | 4,148,457 | 4,148,457 | 4,148,457 | 43.18 |

| 45 | Bacillus subtilis str. GB03** | AYTJ01000000 | Laboratory strain | 3,849,547 | 37 | 20.369 | 485,347 | 387,471 | 227,849 | 46.55 |

| 46 | Bacillus subtilis str. SPZ1** | AQGM01000000 | Laboratory strain | 4,134,697 | 79 | 14.214 | 453,273 | 201,909 | 119,673 | 46.00 |

| 47 | Bacillus subtilis str. NKYL29** | JPYY01000000 | Soil, China | 3,951,956 | 22 | 23.903 | 940,749 | 592,536 | 270,804 | 46.33 |

| 48 | Bacillus sp. EGD-AK10 | AVPM01000000 | Agricultural soil, India | 6,565,134 | 1184 | 14.753 | 731,082 | 292,564 | 3046 | 55 |

| 49 | Bacillus subtilis B7-s | AZNI00000000 | China | 5,313,924 | 82 | 9.097 | ND | 198,717 | 112,914 | 35.1 |

Genomes studied by Yi et al. (2014) which were identified as members of B. subtilis group are marked by a single asterisk (*)

The isolates which are listed in the NCBI database as members of B. subtilis but are clearly not as reported in our study here (Table 3), are marked by **

Type strains of Bacillus subtilis subspecies are identified with a (T)

Library construction and sequencing of the genome of strain D7XPN1 was performed at the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) core facility on an Ion Torrent PGM sequencer using a 318 chip. The sequencing data was converted to FASTQ format and adapters were removed from individual reads. The quality of the sequencing data was assessed using PRINSEQ (http://prinseq.sourceforge.net/) (Schmieder and Edwards 2011). Genomic contigs were assembled from reads using the GS de novo Assembler (Newbler) software (http://454.com/products/analysis-software/index.asp). The assembled draft genome was annotated using Prokka, version 1.10 (Seemann 2014) and the RAST automated annotation pipeline server (http://rast.nmpdr.org/) (Aziz et al. 2008), which employs subsystems technology to identify genes related to different categories of cellular processes and metabolism (Overbeek et al. 2014). The whole-genome shotgun project of Bacillus subtilis strain D7XPN1 (= KCTC 33554, JCM 30051) has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number JHCA00000000. The version described in this paper is version JHCA00000000.1.

Estimation of overall genome relatedness indices (OGRI) for strain D7XPN1

OGRI methods depend on comparisons of whole genome rather than single genes or a set of genes and ANIb has been established as a method of choice. ANIb was performed with genome nucleotide sequences using the calculate_ani.py script (https://github.com/widdowquinn/scripts) that incorporates the ANI algorithm by Richter and Rossello-Mora (2009). In addition, intergenomic e-DDH distances were calculated using Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) with the recommended formula as described by Meier-Kolthoff et al. (2013).

Phylogenomics

The use of groups of orthologous proteins or a set of common conserved genes across genomes is required for phylogenomic analysis and several methods are available for such studies. In our study, we first used Prokka (version 1.10) (Seemann 2014) to identify open reading frames (ORF) of genome nucleotide sequences (n = 43), which were subsequently translated into putative protein sequences and annotated. We then created two protein datasets for phylogenomic studies. For the first, we used the hal pipeline with default settings to find and extract all protein orthologs (Robbertse et al. 2011) and for the second, we used CD-Hit (Huang et al. 2010) to select for a smaller but highly conserved set of orthologuous proteins from the annotations (>97 % AA identity). Additionally, we used the 6 conserved MLST gene dataset (glpF, pta, purH, pycA, rpoD and tpiA) typically used for typing strains of Bacillus subtilis for phylogenomic Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA). The 6 genes were downloaded from pubMLST database and used in local BLAST queries against the Bacillus subtilis genome database of open reading frames (ORF) and the MLST genes retrieved. The datasets of the conserved protein sequences from hal and CD-Hit and the MLST nucleotide sequences were aligned separately using CLUSTALW (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2) (Larkin et al. 2007), concatenated into a single super-alignment and used to construct Maximum Likelihood trees using PhyML (Guindon et al. 2010).

Results

Strain isolation and phylogenetic identification

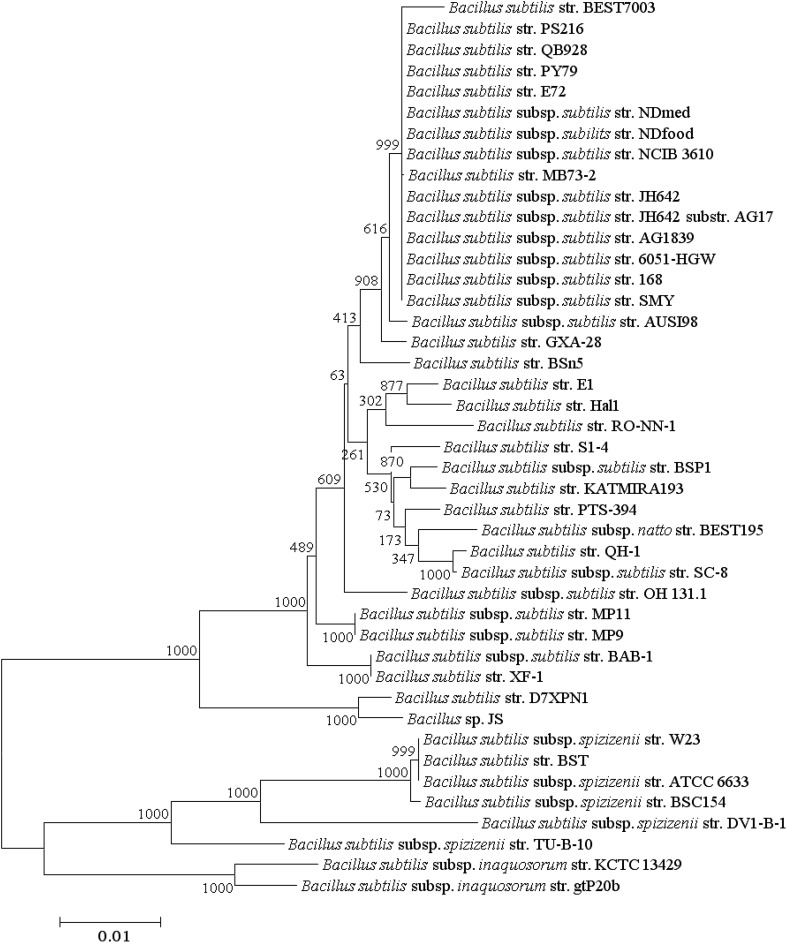

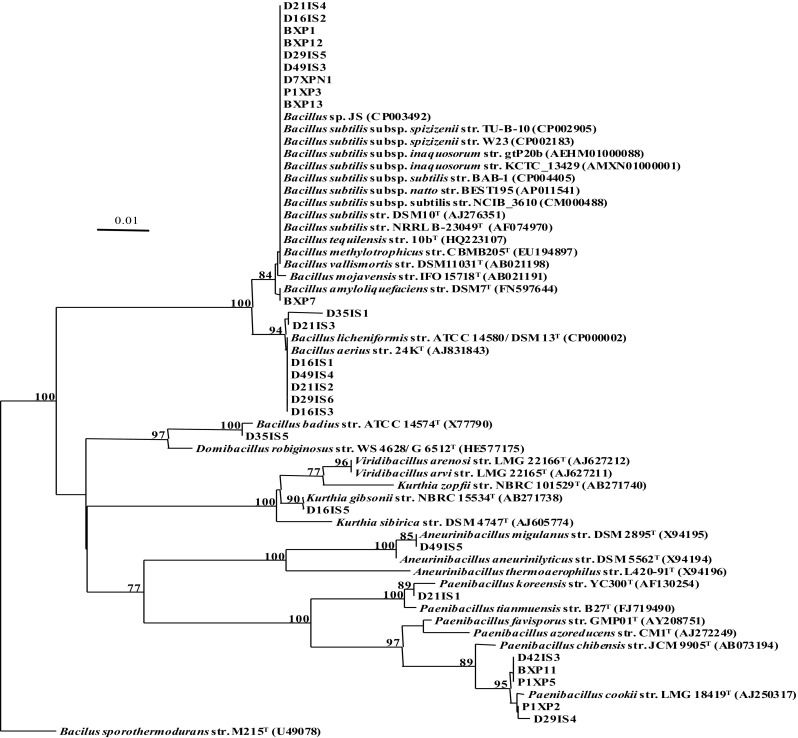

28 strains were isolated from bioreactor samples collected over 49 days of operation. The strains were selected on the basis of differences in colony morphology, growth rates and enzyme screening (amylase and xylanase) (Table 1). 16S rRNA gene (sequence length between 560 and 1555 bp) analysis revealed that 27 of the 28 isolates were members of the genera Bacillus, Paenibacillus, Kurthia and Aneurinibacillus, phylum Firmicutes, domain Bacteria (Fig. 1) whereas the 28th isolate, identified using 18S rRNA gene sequence analysis (sequence length 1738 bp) analysis as Ogataea polymorpha, a yeast (data not shown). Further phylogenetic analysis showed that 9 of the isolates cultured from samples taken from the bioreactor on days 0, 1, 7, 17, 21, 29, and 49 of its operation cycle (Table 1), and which included strain D7XPN1, were closely related to Bacillus subtilis (99 % similarity) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic distance tree constructed from partial 16S rRNA sequences (467 nucleotides) of bacterial strains isolated from samples retrieved from Baku Baku™ a food waste bioreactor. Distance estimation was obtained using the Jukes and Cantor model. Bootstrap percentages after 1000 replications are shown. Scale bar represents one nucleotide change in every 100 nucleotides. Refer to Table 2 for the type strains in this figure

Phenotypic characterization of strain D7XPN1

The cells of strain D7XPN1 were short rods which stained Gram positive and produced cream coloured, opaque, raised, irregular-shaped colonies on dTSA medium. Strain D7XPN1 grew optimally at 45 °C (growth temperature between 24 and 50 °C) suggesting that it was a thermotolerant/moderate thermophile and pH 7 (pH growth range between pH 5 and pH 9). The strain tolerated up to 7 % NaCl (the highest tested) and grew anaerobically by fermentation in the absence of oxygen.

Genome studies of strain D7XPN1

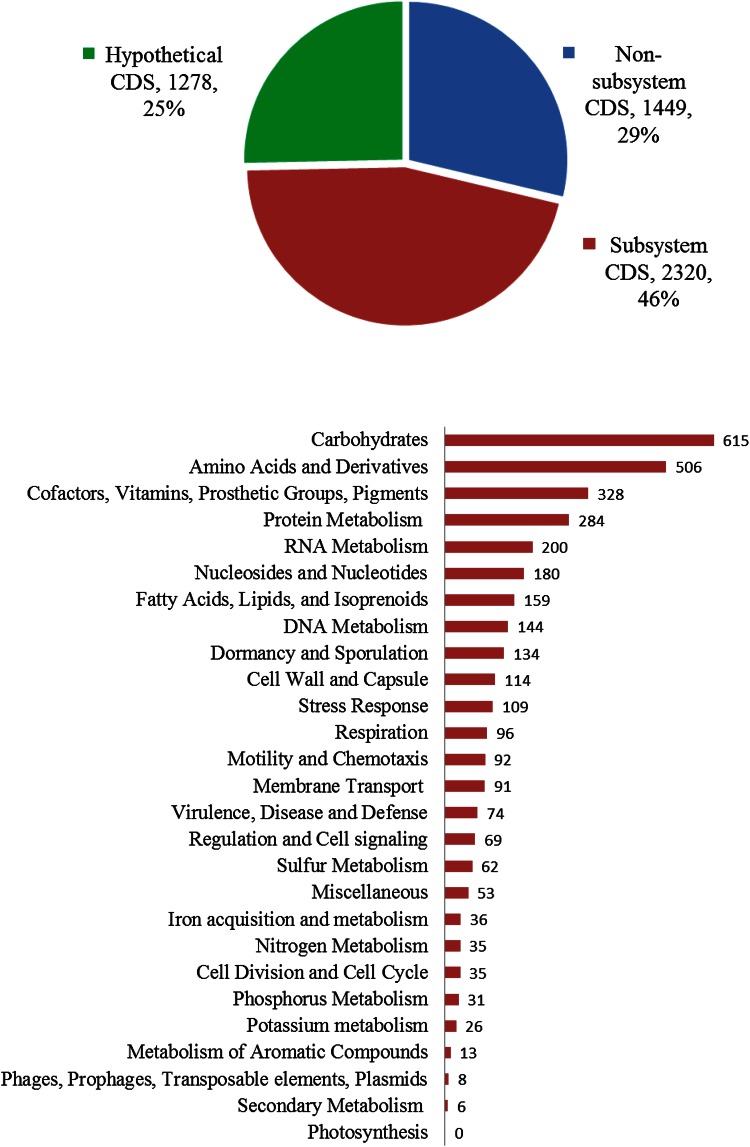

A total 722,222 reads with a mean read length of 196.13 bp (total of 141,651,194 bp) were produced using IonTorrent™. The assembly of these reads with GS assembler (Newbler) produced 28 genomic contigs (average coverage of 40x) with contig sizes ranging from 1,017,528 to 510 bp in length and a N50 of 504,008 bp. RAST server identified a total of 5116 genomic features that included 69 RNA and 5047 protein coding sequences (Fig. 2). Of the 5047 total features, 2,320 were placed into functional subsystems. Two subsystems categories related to carbohydrates and amino acid and derivatives had the highest number of associated features with 615 and 506 coding features, respectively.

Fig. 2.

a RAST annotation gene functional categories of Bacillus subtilis str. D7XPN1. a The pie graph of the total numbers of CDS is divided into 3 categories (in %)—CDS annotations that are represented in the RAST subsystem, those that are not represented (non-subsystem), and those that annotations that are hypothetical. b The bar graph shows the total subsystem CDS annotations by major subsystem categories

Estimation of overall genome relatedness indices (OGRI)

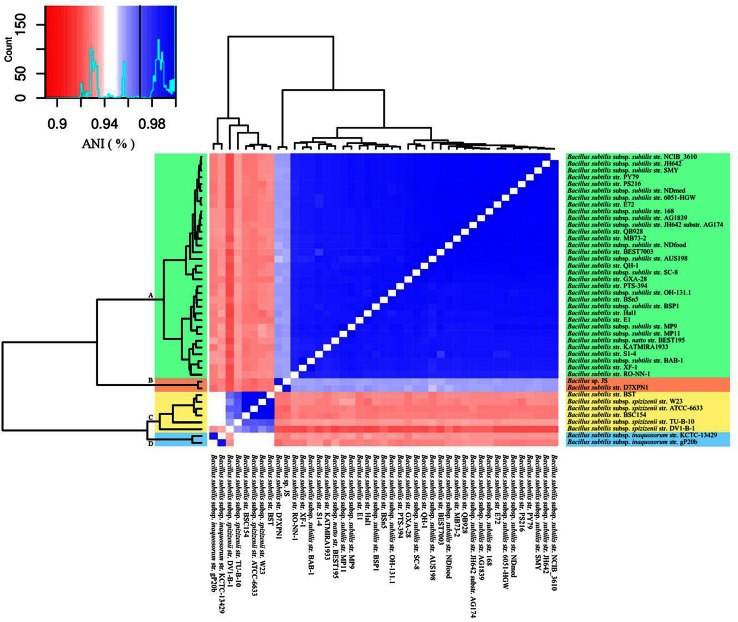

49 strains which had a 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of ≥97 % to B. subtilis strain 168, together with genomes of the members of B. subtilis sensu lato group, B. atrophaeus and strain D7XPN1 were initially used in the ANIb studies (Table 2). The study showed that 43 strains with an ANIb similarity values >92 % could be regarded as members of B. subtilis (Fig. 3) whereas the remaining 6 strains whose similarity values were <92 %, should be examined more closely. Closer examinations showed that B. subtilis strain GBO3, B. subtilis strain SPZ1 and B. subtilis str. NKYL29 shared a high ANIb similarity value (97 %) with B. amyloliquefaciens and B. subtilis subsp. niger str. PCI with B. atrophaeus (99.9 %) (Table 3). Additionally, review of the literature showed that the genome of B. subtilis strain BEST7613 was a chimeric construct of the genomes of Synechocystis strain PCC6803 and B. subtilis 168 (Watanabe et al. 2012) and the examination of the statistics of the genome of B. subtilis B7-S showed that it had a genome that was substantially different in size (5.3 Mb) and in G+C mol % content (35.1) to 43 members of the B. subtilis cluster. These 6 misclassified strains were therefore removed from further analysis.

Fig. 3.

ANIb heatmap of Bacillus subtilis genome sequences (n = 43). Individual genome-to-genome ANIb values are represented in the central bi-color gradient heatmap, the color key shown on the top left had side including adivison line for the recommended subspecies cutoff value (97 %). The heatmap is accompanied by a hierarchical clustering dendrogram with for distinct clades (clusters): B. subtilis subsp. subtilis (A, green), B. subtilis subsp. stecoris (B, pink), B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii (C, yellow) and B. subtilis subsp. inaquosorum (D, blue). Refer to Table 2 for the type strains in this figure

Table 3.

Genomes misclassified as Bacillus subtilis based on ANIb analysis

| Strain | Mean ANI vs species | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | B. amyloliquefaciens | B. atrophaeus | |

| Bacillus subtilis str. GB03 | 0.79581 | 0.97505 | 0.79787 |

| Bacillus subtilis str. SPZ1 | 0.7959 | 0.97518 | 0.79098 |

| Bacillus subtilis str. NKYL29 | 0.7877 | 0.97932 | 0.7903 |

| Bacillus subtilis subsp. niger str. PCI | 0.8104 | 0.79287 | 0.99912 |

Numbers in bold signify the most likely associated species based on the mean of ANIb comparisons to geonomes of the three different species

The remaining 43 strains could be further grouped into 4 clusters based on ANIb similarity values (Fig. 3). Cluster 1 constituted the largest group (33 strains) with a ANIb similarity value of >98 % amongst the members and is represented by the taxonomically validated B. subtilis subsp. subtilis. Of the 33 strains, 16 have already been identified as members of cluster 1. Cluster 2 consists of the two newly isolated strains JS (Song et al. 2012) and D7XPNI (Adelskov and Patel 2014), (Fig. 2) which have an ANIb similarity value of 95.6 % to cluster 1 and to each other by 98.8 %. These two strains have not been taxonomically validated previously and in this report we propose to describe these two strains as members of a new subspecies, B. subtilis subsp stecori of which strain D7XPN1T is the type sub-species. Cluster 3 is composed of two strains of the taxonomically validated B. subtilis subsp. inaquosorum (Table 1) with an ANIb similarity value of 92 and 93 % to clusters 1 and 2, respectively and to each other by 98.6 %. The remaining 6 strains belong to a loose cluster represented by the taxonomically validated B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii which have an ANIb similarity value of between 92 and 94 % with members of clusters 1, 2 and 3. Of the 6 strains, 4 strains have been correctly identified as members of this cluster (Table 2). Of the 6 strains, 4 strains (B. subtilis str. BSC154, B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. W23, B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. ATCC 6633 and B. subtilis str. BST) group closely together (ANIb value of >99 %) whereas B. subtilis subsp. subtilis str. DV1-B-1 and B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. TU-B-10 are more distant (ANIb values of 95.6 and 92.2 %, respectively) to the 4 strains.

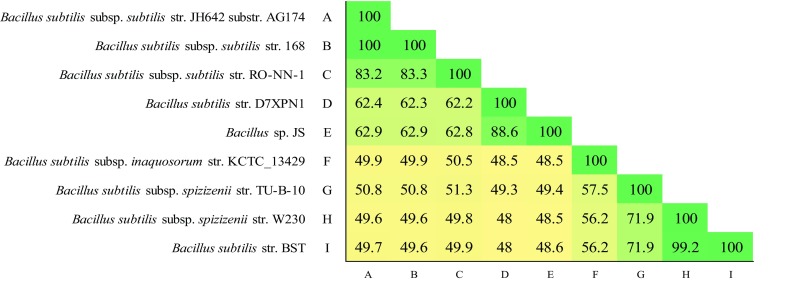

DNA homology using genome-to-genome-distance-calculator (GGDC)

DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) method is a gold standard that is used to differentiate species of the same genus when the 16S rRNA sequence similarity is >97 %. The widely accepted species boundary set by the DDH method is 70 %. The Genome-to-Genome-Distance-Calculator (GGDC) is an in silico alternate for the traditional experimental DDH method and is the second OGRI method used in our study. As all the B. subtilis strains (n = 43) have a 16S rRNA similarity value >97 %, we have calculated the GGDC similarity indices of representatives genomes from each of the 4 sub-species clusters. The results show that B. subtilis subsp. stecori strains D7XPN1 and JS of cluster 2 share a genome similarity of 88.6 % to each other and 62.2–62.9 % with strains of cluster 1 represented by B. subtilis subsp. subtilis and <51 % with strains from the clusters 3 and 4 represented by B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii and B. subtilis subsp. inaquosorum (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

GGDC estimated DNA–DNA Hybridization (DDH, formula 2) of a selected set of B. subtilis genomic strains representing the three current sub-species and the proposed fourth sub-species

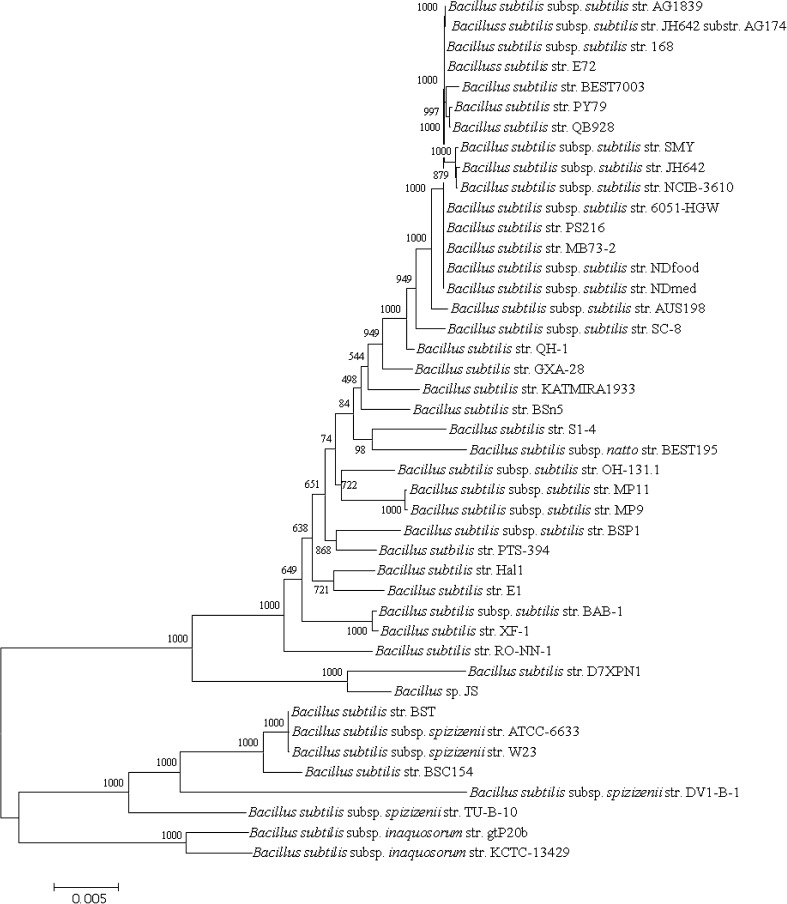

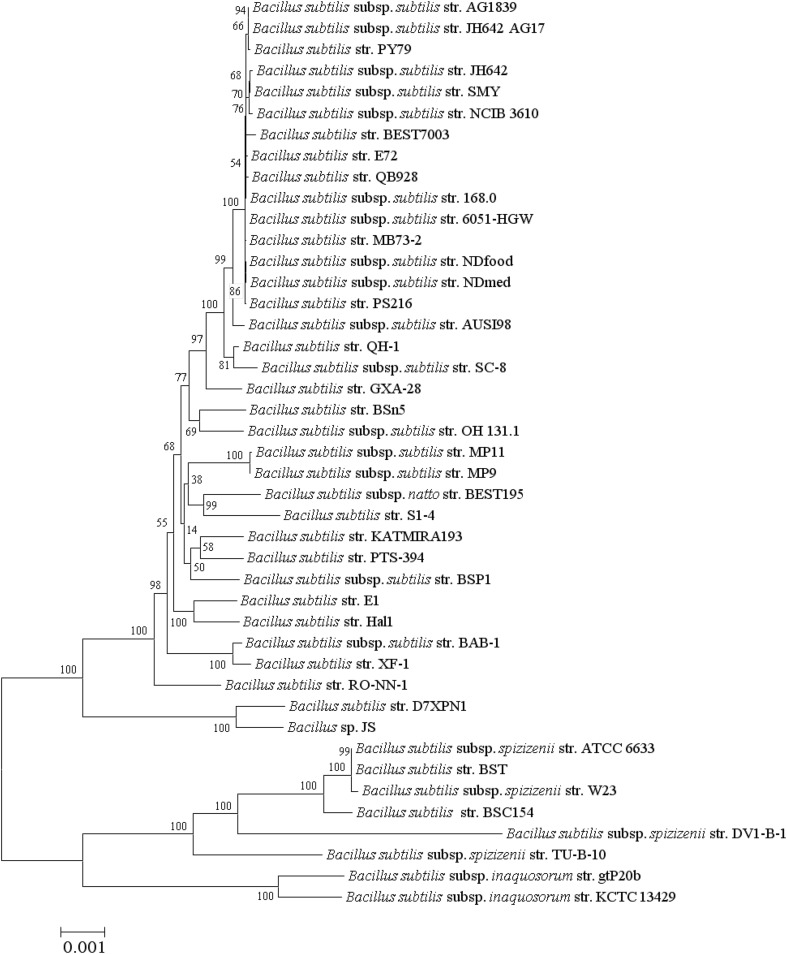

Phylogenomic analysis

Phylogenomic trees produced from the analysis of 1724 core protein sequence orthologs (436,410 aa) and the more conserved 534 protein sequence orthologs generated from CD-Hit analysis (≥97 % amino acids similarity) are presented in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively and the Multi-Locus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) tree generated from the 6 genes routinely used in Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) of B. subtilis strains is shown in Fig. 7. All 3 trees resolve Bacillus strains (n = 43) into 4 clusters with the same topology and with 100 % bootstrap values at each branch point of the clusters and the phylogenomic studies supports the results from genome to genome comparisons studies of ANIb and DDH (Fig. 3) though there are slight changes in the topology of the internal branches of cluster 1 representing B. subtilis subsp. subtilis.

Fig. 5.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of B. subtilis (n = 43) constructed from a superalignment of sequences from 1724 protein orthologs of B. subtilis genomes using the hal pipeline with default parameters. Distances were corrected using the Jone-Taylor (JTT) model with 1000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates. The bootstrap values are represented by numbers at nodes. Scale bar indicates 5 differences in every 1000 amino acids (0.5 %). Refer to Table 2 for the type strains in this figure

Fig. 6.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of B. subtilis (n = 43) produced from a superalignment consisting of conserved sequences of 512 protein orthologs (>97 %). Distances were corrected using the Jones -Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model with 1000 non-parametric bootsrap replicates and the values (in percent) are represented at each node. The scale bar represents a difference of 1 in every 1000 amino acids (0.1 %). Refer to Table 2 for the type strains in this figure

Fig. 7.

Multi-locus sequence analysis (MLSA) maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of B. subtilis produced from a superalignment of 8861 nucleotide sequences of glpF, pta, purH, pycA, rpoD and tpiA. Distances were corrected using the model of Hasegawa et al. (1985) with 1000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates. The bootstrap values are represented at each node. Scale bar represents a difference of 1 in 100 nucleotides (1 %). Refer to Table 2 for the type strains in Table 1

Discussion

It is well-established that 16S rRNA phylogeny does not readily separate closely related strains of Bacillus subtilis and including differentiating phenotypic characteristics to phylogenetic data does not necessarily assist in taxonomic delineation. For example, dark pigmented colonies are a distinctive feature of B. atrophaeus but some strains of B. subtilis also produce such colonies (Nakamura 1989). Several recent studies have discussed the need to establish microbial taxonomy on the basis of information retrieved from microbial genomes especially when 16S rRNA similarity values are >97 % and many computational methods, which can be categorised into two broad groups, have been reported in the literature (Bull et al. 2012; Larsen et al. 2014). Computational methods which rely purely on comparison of nucleotide sequences of genomes, have been recently coined by Chun and Rainey (2014) as Overall Genome Relatedness Indices (OGRI) methods and include ANI, GGDC, GBDP (Genome Blast Distance Phylogeny), Maximal Unique Matches Index (MUMi) whereas methods which rely on comparison of conserved genomic features (e.g. core genes and proteins) where sequence disparities are the result of evolutionary pressures, are known as phylogenomic methods.

In this study we isolated 28 strains from a food-waste degrading commercial bioreactor of which 9 isolates could only be assigned as strains of B. subtilis based on 16S rRNA sequence analysis (Fig. 1). We selected strain D7XPN1 as representative of the 9 isolates, sequenced and using OGRI (ANIb and DDH) and phylogenomic methods compared it’s genome with genomes of B. subtilis and B. subtilis-like strains that had been retrieved from NCBI database. For this we initially downloaded 49 B. subtilis genomes but were left with only 43 after identifying and removing mixed or misclassified genomes. Of these remaining genomes of 43 B. subtilis strains, 21 strains had already been used by Yi et al. (2014) in their studies and our results support their conclusions that ANIb can be used to separate B. subtilis into 3 subspecies. They had further suggested that if the threshold ANIb value of 95–96 % were to be used for species delineation than B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii and B. subtilis subsp. inaquosorum should be designated as new species. ANIb analysis of the additional 22 strains which were not part of the studies of Yi et al. (2014) revealed that 20 could be assigned to one of the 3 clusters defined by Yi et al. (2014) but a further 2 strains, strains JS and D7XPN1, were closely related to each other (ANib value of 98.8 %) and formed a separate cluster, designated cluster 2. Cluster 2 was a sister branch of cluster 1 and was more closely related to it than to clusters 3 and 4 (ANIb values of 95.6, 93 and 92–94 %, respectively).

Based on the conservative cut off DDH value of 70 %, B. subtilis strains (n = 43) can be assigned to 4 clusters, each represented by a subspecies and is consistent with the findings of the ANIb analysis. The results also confirm that strains D7XPN1 and JS are related more closely to each other than to members of cluster 1 represented by B. subtilis subsp. subtilis and supports results from the ANIb analysis. In addition, all the 3 phylogenomic trees generated using 3 different data sets (1724, 534, and 6 core orthologs) resolve Bacillus strains (n = 43) into 4 clusters with the same topology and with 100 % bootstrap values at each branch point of the clusters and the phylogenomic studies supports the results from genome to genome comparisons studies of ANIb and DDH studies though there are slight changes in the topology of the internal branches of cluster 1 representing B. subtilis subsp. subtilis.

Phylogenomic studies indicate that there are differences in the gene and protein content of the 43 strains. Doolittle and Zhaxybayeva (2009) have hypothesised that the acquisition of genes can affect changes in an ecological niche and that even the closest relatives could be ecologically distinct ecotypes. Kopac et al. (2014) in their studies on B. subtilis subsp. spizizenii (cluster 4), which has 6 members, 4 of which were isolated from Death Valley, showed that all the genomes of the four Death Valley strains differed in gene content supporting the hypothesis of Doolittle and Zhaxybayeva (2009) that even the closest relatives could be ecologically distinct ecotypes. However, Kopac et al. (2014) were unable to demonstrate if the acquisition of genes could in fact change the metabolic dynamism of the ecological niche.

It would be interesting to extend the studies to B. subtilis subsp. subtilis (cluster 1) the most widely represented strains in B. subtilis but for the fact that the strains have been isolated from a very wide range of environments and therefore any differences found in the gene content could be considered to be biased due to habitat differences. We have in our study reported here 9 strains of B. subtilis isolated from samples taken from the bioreactor on days 0, 1, 7, 17, 21, 29, and 49 of its operation cycle (Table 1), all of which are closely related (16S rRNA similarity >99 % similarity). Strain D7XPN1 reported in our studies, was isolated from a sample collected on day 7 and is a representative of the nine B. subtilis strains. Strain D7XPN1 is capable of growing at moderate thermophilic temperatures and contains an array of enzymes for degradation of polysaccharides including a xylanase and an amylase. We intend to sequence and compare the genomes of all the 9 strains and if the hypothesis of Doolittle and Zhaxybayeva (2009) holds true then we should be able to see differences in the gene profiles which would potentially be reflective of the change in environmental conditions in the waste-degrading bioreactor, from day 0 to day 49.

The genome of strain JS isolated from the soil of a pot planted with Miscanthus sp. was sequenced and a number of genes associated with plant growth promoting and antifungal activities were identified (Song et al. 2012). In addition, the use of volatile extracts of strain JS were found to reduce the disease in bacterial infected tobacco plants (Kim et al. 2015). Our analysis of the annotations of the genome of strain D7XPN1 has also identified potential plant growth-promoting genes similar to those found in strain JS. The properties of strain D7XPN1 has potential for use as an inoculum source to improve and increase efficiency of the food-waste degradation process at thermophiic temperatures but additionally, it also has the potential for use as a plant growth promoting fertilizer at the completion of the degradation process.

Strains JS and D7XPN1 have not yet been taxonomically validated but based on the OGRI and phylogenomic results reported here, we propose to describe these two strains as members of a newly created subspecies that we designate B. subtilis subsp stecori of which strain D7XPN1T is the type sub-species. Furthermore, we propose that once more strains of clusters 2, 3 and 4 have been isolated and their genome sequences analysed than if necessary, the reassignment of the B. subtilis strains should be reconsidered given the low ANIb (≤95–96 %) and DDH values (<70 %) which demarcate each of the fourclusters.

Description of Bacillus subtilis subsp. stecoris subsp. nov

Bacillus subtilis subsp. stecoris [ste.co.ris.L. gen. n. compost, from which the strain was isolated]. Grows optimally at 45 °C (range 24–50), pH of 7 (range 5–9), and grew in the presence of 7 % NaCl. Facultative anaerobe by fermentation, forms white irregular colonies 1–2 mm in diameter when grown on dTSA, cells are straight rods 4–5 µm length by 1 µm width, and stain Gram positive. Degrades potato starch by amylase activity and expresses partial β-xylanase activity detected when grown on dTSA with x-β-D-xyloside.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Browning for sample collection and Exact Energy, Gold Coast, Australia, for funding the project. The sequencing of the genome and general genome sequence analysis was completed as part of a BSc (Hons.) thesis by Joseph Adelskov, currently an APA scholarship awardee. IT infrastructure provided by National eResearch Collaboration Tools and Resources (NeCTAR) Project provided is gratefully acknowledged.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0747-0.

References

- Adelskov J (2013) Microbial community structure and function in the degradation of food wastes under controlled conditions. Honours Thesis, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland

- Adelskov J, Patel BK. draft genome sequence of Bacillus subtilis strain D7XPN1, isolated from commercial bioreactor-degrading food waste. Genome Announc. 2014 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00989-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull MJ, Marchesi JR, Vandamme P, Plummer S, Mahenthiralingam E. Minimum taxonomic criteria for bacterial genome sequence depositions and announcements. J Microbiol Methods. 2012;89:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Rainey FA. Integrating genomics into the taxonomy and systematics of the bacteria and archaea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:316–324. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.054171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle WF, Zhaxybayeva O. On the origin of prokaryotic species. Genome Res. 2009;19:744–756. doi: 10.1101/gr.086645.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Gong Y, Huo Y, Han Q, Kang Z, Huang L. Endophytic Bacillus subtilis strain E1R-J is a promising biocontrol agent for wheat powdery mildew. Biomed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/462645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22:160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Niu B, Gao Y, Fu L, Li W. CD-HIT Suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:680–682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein AH, Lisowska BK, Leak DJ. The genus Geobacillus and their biotechnological potential. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2015;92:1–48. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Lu G, Gai Y, Zheng C, Mu Z. Biological control against bacterial wilt and colonization of mulberry by an endophytic Bacillus subtilis strain. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65:565–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanso S, Greene AC, Patel BK. Bacillus subterraneus sp. nov., an iron- and manganese-reducing bacterium from a deep subsurface Australian thermal aquifer. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:869–874. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Lee J, Lee CH, Woo SY, Kang H, Seo SG, Kim SH. Activation of Pathogenesis-related Genes by the Rhizobacterium, Bacillus sp. JS, which induces systemic resistance in tobacco plants. Plant Pathol J. 2015;31:195–201. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.NT.11.2014.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopac S, Wang Z, Wiedenbeck J, Sherry J, Wu M, Cohan FM. Genomic heterogeneity and ecological speciation within one subspecies of Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4842–4853. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Lukjancenko O, Saputra D, Rasmussen S, Hasman H, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Aarestrup FM, Ussery DW, Lund O. Benchmarking of methods for genomic taxonomy. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1529–1539. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02981-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan H, Van der Auwera G. Bacillus taxonomy in the genomic era finds phenotypes to be essential though often misleading. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Goker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura LK. taxonomic relationhip of black-pigmented Bacillus subtilis strains and a proposal for Bacillus atrophaeus sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:295–300. doi: 10.1099/00207713-39-3-295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg CD, Patel BK. Caloramator australicus sp. nov., a thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium from the Great Artesian Basin of Australia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:95–101. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F, Stevens R. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redburn AC, Patel BK. Desulfovibrio longreachii sp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from the Great Artesian Basin of Australia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Rossello-Mora R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbertse B, Yoder RJ, Boyd A, Reeves J, Spatafora JW (2011) Hal: an automated pipeline for phylogenetic analyses of genomic data PLoS Curr 3:RRN1213 doi:10.1371/currents.RRN1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roberts MS, Nakamura LK, Cohan FM. Bacillus mojavensis sp. nov., distinguishable from Bacillus subtilis by sexual isolation, divergence in DNA sequence, and differences in fatty acid composition. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:256–264. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-2-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MS, Nakamura LK, Cohan FM. Bacillus vallismortis sp. nov., a close relative of Bacillus subtilis, isolated from soil in Death Valley, California. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:470–475. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Kim HA, Kim JS, Kim SY, Jeong H, Kang SG, Kim BK, Kwon SK, Lee CH, Yu DS, Kim BS, Kim SH, Kwon SY, Kim JF. Genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus sp. strain JS. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3760–3761. doi: 10.1128/JB.00676-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesth T, Lagesen K, Acar O, Ussery D. CMG-biotools, a free workbench for basic comparative microbial genomics. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Shiwa Y, Itaya M, Yoshikawa H. Complete sequence of the first chimera genome constructed by cloning the whole genome of Synechocystis strain PCC6803 into the Bacillus subtilis 168 genome. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:7007. doi: 10.1128/JB.01798-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler S, Woese CR. A definition of the domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya in terms of small subunit ribosomal RNA characteristics. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:305–310. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Chun J, Cha CJ. Genomic insights into the taxonomic status of the three subspecies of Bacillus subtilis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2014;37:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick ME, Joseph SJ, Didelot X, Chen PE, Bishop-Lilly KA, Stewart AC, Willner K, Nolan N, Lentz S, Thomason MK, Sozhamannan S, Mateczun AJ, Du L, Read TD. Genomic characterization of the Bacillus cereus sensu lato species: backdrop to the evolution of Bacillus anthracis. Genome Res. 2012;22:1512–1524. doi: 10.1101/gr.134437.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]