Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare the incidence of the different histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma between the United States of American (US) and India. The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database was analyzed to determine the incidence of different types of esophageal carcinoma in US. A retrospective review was conducted of all the patients that underwent resection for esophageal carcinoma at a regional oncology center in India from 2001 to 2007. Data relating to histopathologic variables was collected and compared to the patients in the SEER database for the same time period. Esophageal adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority of newly diagnosed cases in the US. Although squamous cell carcinoma is the dominant type of esophageal carcinoma in India, we noted a small but gradual increase (0 % in 2001 to 28 % in 2007) in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The results of our study demonstrate a geographic variation in the histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma. A recent increase in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in India was also demonstrated. Analysis of risk factors known to be associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma, in the context of India, can provide targets for implementing public health measures.

Keywords: Esophageal neoplasms, Westernization, Geographic variance in neoplasms

Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma is the eighth most prevalent carcinoma and the sixth leading cause of carcinoma-related mortality in the world [1]. The reported 5-year survival is in the range of 15–20 % for patients in the United States (US) [2, 3]. Behavioral factors such as diet, physical activity, smoking, and drinking behavior influence the distribution of diseases, including esophageal carcinoma, in a population [4, 5]. In India, traditional diets high in fruit, vegetables, and legumes and low in animal fat and salt were common; however, changes in typical Indian diets have accompanied India’s westernization and urbanization such that the consumption of wheat, high protein, and energy-dense foods have increased [6]. Likewise, cultural changes in India appear to have contributed to decreasing levels of physical activity [7] and an increase in obesity [8].

In light of the impact of body-mass index (BMI), physical inactivity, and diet on non-communicable diseases such as cancer, it is reasonable to anticipate related changes in the distribution of diseases in India which reflect relatively recent changes in Indian culture. In particular, Barrett’s esophagus, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) are linked to obesity and low consumption of fruit and vegetables [9]. Thus, as India becomes increasingly more westernized, clinicians and public health professionals can anticipate an increase in carcinomas such as EAC which are sensitive to diet, BMI, and physical inactivity.

On the other hand, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), the most common histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma worldwide [4, 5], is related to risk factors such as smoking and alcohol use [6, 7] which are not unique to westernization.

Previous research has not addressed whether changes in westernization and urbanization in India have changed the prevalence of ESCC and EAC. This study sought to examine trends in the incidence of ESCC and EAC in India and compare it to data from the US.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective case review was performed of all patients diagnosed with esophageal carcinoma at the Mehdi Nawaz Jung Institute of Oncology (MNJIO), a regional oncology center in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India between 2001 and 2007. The study was approved by the appropriate hospital authorities in India. Data pertaining to demographics, type of operation and year of operation were collected. Pathology reports of all patients were reviewed to identify the histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma.

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database collects information regarding incidence, prevalence, survival and mortality for carcinoma patients in the US and represents approximately 26 % of the population [10]. The SEER database was accessed to identify patients diagnosed with esophageal carcinoma between 1973 and 2007, and the histopathologic type of each carcinoma was determined.

All statistical analysis was performed using the SEER data to determine any changing trends in the histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma in the United States when compared to the data from India. We performed an initial comparison of the SEER database to the matched time period of data that was available from MNJIO (2001–2007). We then analyzed the SEER data from 1973 to 2007 in quartiles for trends in prevalence of histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma in the US. Since obesity is considered to be a risk factor for EAC, we also correlated the trends in obesity rates in the US with the incidence of EAC in the SEER database.

Results

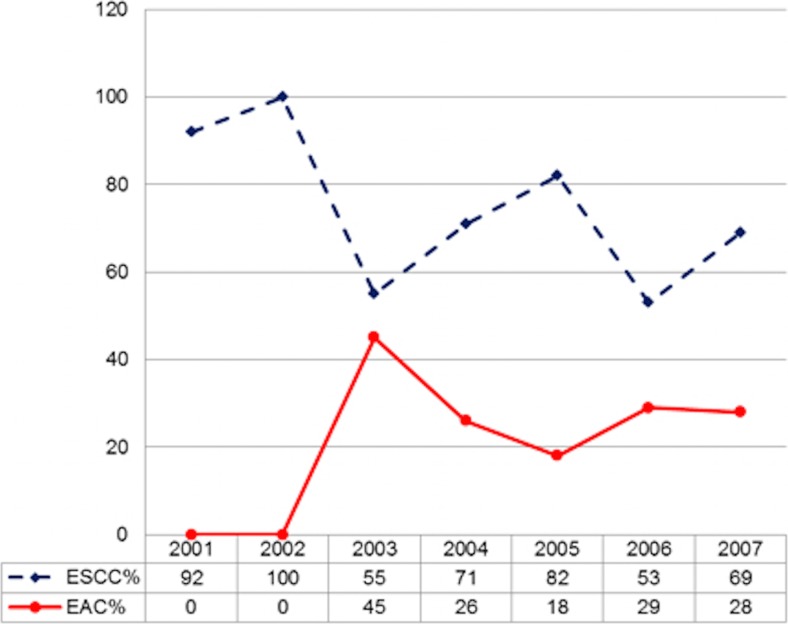

A total of 143 patients from India were included in the study with a mean age of 50.8 years and a male preponderance of 52 %. The histopathologic details of patients with esophageal carcinoma at MNJIO from 2001 to 2007 are shown in Fig. 1. ESCC accounted for nearly three-fourths of the cases seen during the study period. EAC accounted for 24 % of cases in the entire study. We noted a rising trend in the percent of cases with EAC seen in the later part of the study period at MNJIO (0 % in 2001 to 28 % in 2007).

Fig. 1.

Incidence of different histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma at MNJIO, India(2001–2007)

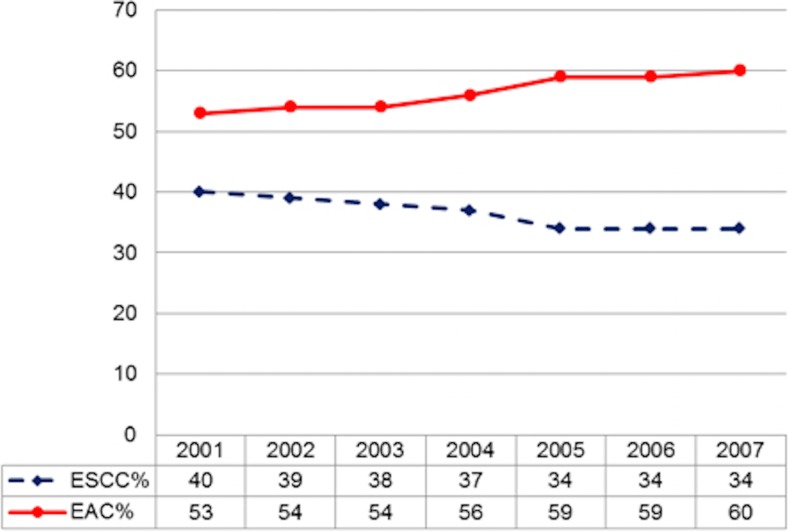

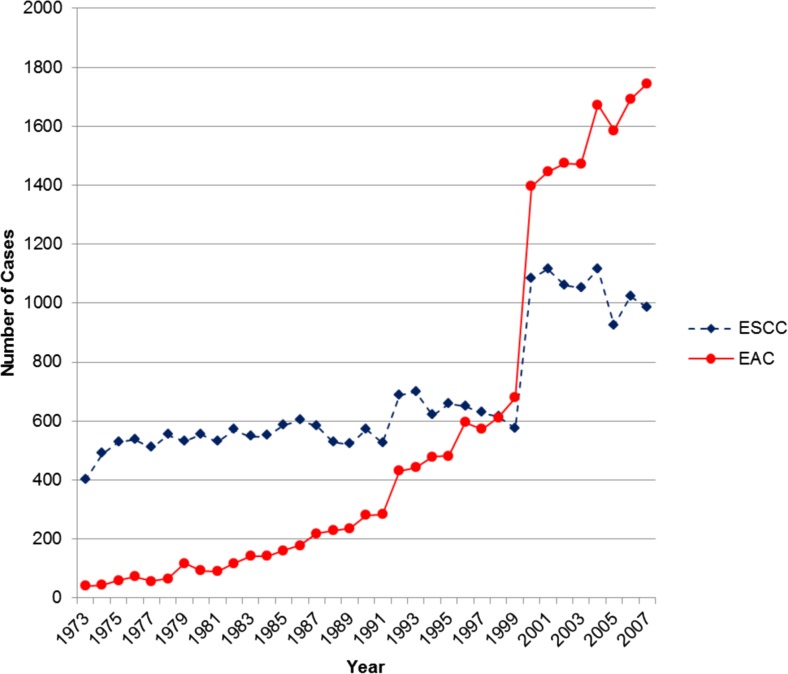

The incidence of the histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma for the matched time period in the US (2001–2007), from the SEER database, is shown in Fig. 2. The prevalence of EAC continued to rise in the US and represented 60 % of the new esophageal carcinoma cases diagnosed in 2007. Similarly, during this time period, the prevalence of ESCC decreased and accounted for 34 % of the newly cases diagnosed in 2007. Analysis of the SEER trends in histopathologic types of esophageal carcinomas, for the time period from 1973 to 2007 (in quartiles), revealed a significant increase in the percentage of new cases of EAC (from 7 % in the seventies to 56 % for the most recent time quartile). This is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Incidence of different histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma in US (SEER 2001–2007)

Fig. 3.

Incidence of different histopathologic types of esophageal carcinoma in US (SEER 1973–2007)

Discussion

Considering the influence of weight and dietary factors on chronic non-communicable diseases, it is reasonable to anticipate some changes in the prevalence and distribution of diseases in India, which has experienced significant westernization and urbanization, including a more westernized diet and a decrease in physical activity. Such changes in culture influence the health of the population. The aim of this study was to examine trends in the incidence of ESCC and EAC in India and compare it to data in the US to determine whether there exist geographic variations in histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma.

Over the last two decades, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction has progressively increased in the US. EAC is noted to have the fastest rising incidence rate for any carcinoma in the US over the past decade. We noted that EAC accounted for 56 % of all the new cases of esophageal carcinoma diagnosed during the time period from 2001 to 2007. These findings have been noted by other authors as well. Brown et al. and Altekruse et al. reported that EAC currently accounts for approximately 58 % of all new cases of esophageal carcinoma, with ESCC accounting for another 29 % (including epidermoid carcinoma in ESSC) [5, 10].

In contrast, in India, where esophageal carcinoma is considered endemic, ESCC continues to be the most common type of esophageal carcinoma. Although ESCC is still the dominant type of esophageal carcinoma in India, we noted a gradual but steady increase in the incidence of EAC over the period of this study (2001–2007) at MNJ. The reasons for this increase in the incidence of EAC are unclear. The risk factors contributing to the development of ESCC and EAC are different. Of the several risk factors known to be associated with EAC, obesity is critical. In a meta-analysis of nine studies, Hampel, et al. noted that obesity is associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The odds ratio for developing EAC was 1.52 (95 % CI 1.147–2.009) for those with a BMI of 25 to 30 kg/m2 and increased to 2.78 (95 % CI 1.850–4.164) for those with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 [11]. Similarly, Lanergern et al. reported a weight-dependent relation between BMI and EAC and documented that obese persons with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m (2) had the highest risk (OR = 16.2, CI 6.3–41.4) [12].

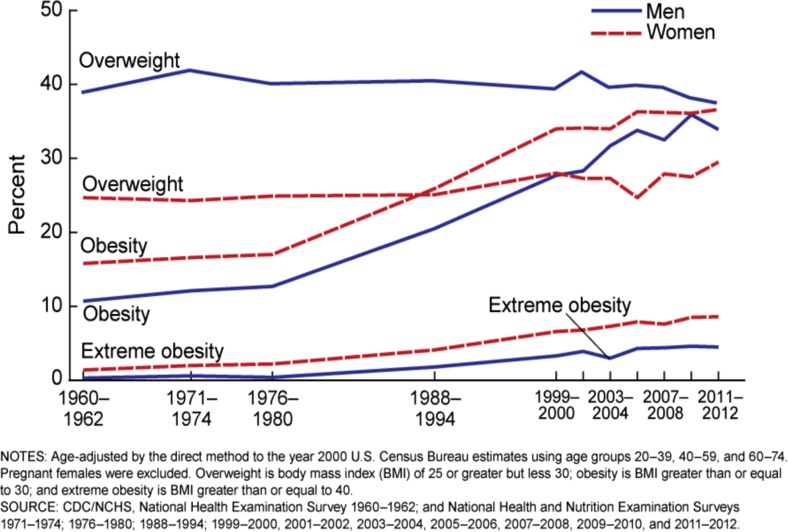

Trends in the US rates of obesity are shown in Fig. 4 [13]. We noted that there was an inflection point during the time period of 1976–1980, following which there was a significant rise in the rates of obesity. This corresponds to the time period when cases of EAC were initially reported. However, it is important to note that there was a lag period of several years between the rise in obesity rates and substantial increase in the incidence of EAC.

Fig. 4.

Trends in adult overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among men and women aged 20–74: United States, selected years 1960–1962 through 2011–2012

It is well known that obesity is on the rise in developing countries such as India. One study reported that obesity rates have doubled over the past decade in India (1.3 to 2.8 %) [14]. In a different study it was found that overweight and obese patients now make up more than 10 % of the population [15].

Although beyond the purview of this study, it can be speculated that the rise in the incidence of EAC in India could be related to the rise in the rates of obesity. This is worthy of further investigation as the findings of such a study can have significant implications. In the US there was a lag phase of several years between the rise in obesity and the significant increase in the incidence of EAC. If an association between BMI and EAC can be substantiated in India, the lag phase can provide the window to implement public health and preventive measures against esophageal carcinoma.

Given the context of cultural changes in India which may be conducive to higher prevalence of obesity and low consumption of fruit and vegetables, clinicians and public health professionals should be mindful of these behavioral factors which predispose patient populations to Barrett esophagus, GERD, and EAC [9]. In addition, Indian public health professionals may consider implementing cancer prevention programs and more robust cancer registry infrastructure. Likewise, individual, family and community-based approaches to health promotion and disease prevention are essential for successful prevention of obesity and related chronic non-communicable diseases including cancer. Implementing culturally appropriate public health measures that address risk factors may counter the likely rise in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in India and other developing nations.

There are several limitations to a comparative study of this design. We compared the data from a regional oncology center in India to a nation-wide cancer registry in the United States. Although cancer registries are available in India and are being improved upon they are not as comprehensive as US registries. Secondly, to obtain the greatest degree of accuracy, we utilized chart and pathology review data that we collected ourselves rather than relying on a pre-existing database or third party case review. We reviewed the records of only those patients that underwent operative intervention at MNJIO hospital. Records of patients that did not undergo operative intervention were not available. It is likely that addition of these patients may have an influence on the total numbers of different types of esophageal carcinoma.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of our study demonstrate a geographic variation in the histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma. Though ESCC was previously the predominant type, EAC is now the most common histopathologic type of esophageal carcinoma in the United States. These trends occurred during a time period when the prevalence of overweight and obese individuals increased in the US. Although ESCC is currently the dominant type in India, during the study period we noted a small but gradual increase in EAC incidence there. The risk factors that are known to have contributed to the rise in EAC in the US, particularly obesity should be analyzed in the context of India to determine the presence of any association. Future studies could address whether this trend is occurring across at other oncology centers in India as well as other areas of the developing world.

References

- 1.Global Cancer Facts and Figures. Am Cancer Soc website. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/globalfactsandfigures2007rev2p.pdf. 2007. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

- 2.Graham AJ, Shrive FM, Ghali WA, et al. Defining the optimal treatment of locally advanced esophageal cancer: a systematic review and decision analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esophageal Cancer. Am Cancer Soc website. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003049-pdf.pdf. 2015. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

- 4.World Cancer Research Fund . American Institute for Cancer Research.: food, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaefer EJ. Lipoproteins, nutrition, and heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:191–212. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pingali P. Westernization of Asian diets and the transformation of food systems: Implications for research and policy. Food Policy. 2007;32(3):281–298. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veugelers PJ, Porter GA, Guernsey DL, et al. Obesity and lifestyle risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(5):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Statistics 2010. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2010/en/index.html. 2010. Accessed 2 Jun 2010

- 9.Anjana RM, Pradeepa R, Das AK, et al. Physical activity and inactivity patterns in India–results from the ICMR-INDIAB study (Phase-1)[ICMR-INDIAB-5] Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Cancer Incidence: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registries Research. Nat Can Institute website. http://seer.cancer.gov. 2015. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

- 11.Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(3):199–211. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-3-200508020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(11):883–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Diseases Control’s National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Centers for Disease Control website.: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_11_12/obesity_adult_11_12.pdf. 2012. Accessed 18 Apr 2015

- 14.World Health Statistics 2010. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2010/en/index.html. 2010. Accessed 2 Jun 2010

- 15.India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) 2005–06 Key Findings. Indian Nat Fam Health Survey website. http://www.nfhsindia.org/. 2006. Accessed 15 Aug 2010