Abstract

Background and purpose — We developed a marker-free automated CT-based spatial analysis (CTSA) method to detect stem-bone migration in consecutive CT datasets and assessed the accuracy and precision in vitro. Our aim was to demonstrate that in vitro accuracy and precision of CTSA is comparable to that of radiostereometric analysis (RSA).

Material and methods — Stem and bone were segmented in 2 CT datasets and both were registered pairwise. The resulting rigid transformations were compared and transferred to an anatomically sound coordinate system, taking the stem as reference. This resulted in 3 translation parameters and 3 rotation parameters describing the relative amount of stem-bone displacement, and it allowed calculation of the point of maximal stem migration. Accuracy was evaluated in 39 comparisons by imposing known stem migration on a stem-bone model. Precision was estimated in 20 comparisons based on a zero-migration model, and in 5 patients without stem loosening.

Results — Limits of the 95% tolerance intervals (TIs) for accuracy did not exceed 0.28 mm for translations and 0.20° for rotations (largest standard deviation of the signed error (SDSE): 0.081 mm and 0.057°). In vitro, limits of the 95% TI for precision in a clinically relevant setting (8 comparisons) were below 0.09 mm and 0.14° (largest SDSE: 0.012 mm and 0.020°). In patients, the precision was lower, but acceptable, and dependent on CT scan resolution.

Interpretation — CTSA allows detection of stem-bone migration with an accuracy and precision comparable to that of RSA. It could be valuable for evaluation of subtle stem loosening in clinical practice.

Continuous migration of joint implants over time is an early predictor of failure (Ryd 1992, Freeman and Plante-Bordeneuve 1994, Kärrholm et al. 1994, Krismer et al. 1996, Kärrholm et al. 1997, Alfaro-Adrian et al. 1999, Krismer et al. 1999, Scheerlinck and Casteleyn 2006, Hauptfleisch et al. 2006, Kroell et al. 2009, Voort et al. 2015). This allows identification of inferior implants before clinical failure sets in, and without exposing large numbers of patients to unnecessary risks (Nilsson and Kärrholm 1996, Kärrholm et al. 1997). At the individual level, early identification of implant migration is valuable for assessment of a painful prosthesis without obvious signs of loosening, and to decide on a revision before further bone destruction sets in (Mjöberg et al. 1984, 1985, Ryd 1992).

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) (Valstar et al. 2005) and Ein Bild Roentgen analysis (EBRA) (Biedermann et al. 1999, Hamadouche et al. 2001) are currently in use for assessment of bone-implant migration. However, both methods have drawbacks. RSA is a research tool that requires the insertion of bone markers, making the technique unsuitable for evaluation of implant loosening in patients who have not been given such markers initially. Moreover, RSA requires a calibration cage and an expensive research setup to take repeated radiographs with simultaneous exposure at a fixed angle. Even so, it is the gold standard. It allows quantification of 3D implant migration with an accuracy that is generally inferior to 0.1 mm for translations and 0.5° for rotations (Kärrholm et al. 1997, Østgaard et al. 1997, Önsten et al. 2001, Li et al. 2014). Yet, precision can drop to 0.7 mm in the anteroposterior direction (Kärrholm 1989). RSA can be used to detect longitudinal implant migration during follow-up (Voort et al. 2015) and inducible displacement under stress conditions (Mjöberg et al. 1984).

EBRA is based on a direct comparison of radiographs taken during follow-up. As it does not require markers, it is applicable to any patient. However, compared to RSA, EBRA has been found to have lower accuracy (e.g. ≤1 mm (Phillips et al. 2002), <1.5 mm (Biedermann et al. 1999), or 1.6–2 mm (Beaulé et al. 2005)). Moreover, the technique cannot measure anteroposterior or rotational implant migration and is sensitive to patient positioning (Biedermann et al. 1999, Ilchmann et al. 2006).

To avoid the drawbacks of these current methods, we developed an automated “marker-free” CT-based spatial analysis (CTSA) technique for assessment of migration of femoral hip implants. Such a tool can be used on a large scale, with a minimal amount of investment, and in patients who have not been included in an ongoing study. We previously presented at meetings a feasibility study (Vandemeulebroucke et al. 2013, see Supplementary data) and a performance study of the CTSA method with respect to zero-migration (Polfliet et al. 2015, see Supplementary data).

This study compares the accuracy and precision of CTSA and RSA.

Material and methods

Mechanical model and CT scan technique

To evaluate our newly developed marker-free CTSA technique, we cemented a cobalt-chromium alloy polished tapered stem instrumented with a distal centralizer (CPT stem size 1; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) in a dry macerated human femur as described previously (Scheerlinck et al. 2005). After curing of the cement, the CPT stem could be removed and reinserted into the cement mantle without damage.

The specimen was scanned with a Somatom Definition AS40 spiral CT scanner (Siemens AG, Erlanger, Germany) with the following settings: beam collimation 20 × 0.6 mm, tube current 200 mAs, tube potential 140 kVp, pitch 0.8, pixel spacing 0.18 mm, and a field of view 90 mm. Images were reconstructed with a B80s filter and a slice thickness of 0.6 mm with an increment of 0.3 mm. The volume CT dose index (CTDIvol) and dose length product (DLP) of the experimental protocol were 24.7 mGy and 600 mGy·cm respectively, yielding a potential effective dose (ED) of 5.8 mSv. We calculated the effective dose following ICRP-103 guidelines (Ann ICRP 2007) with a CT patient dosimetry calculator (CT Expo version 2.1; Medizinische Hochschule, Hannover, Germany).

Automated analysis of CT scan images

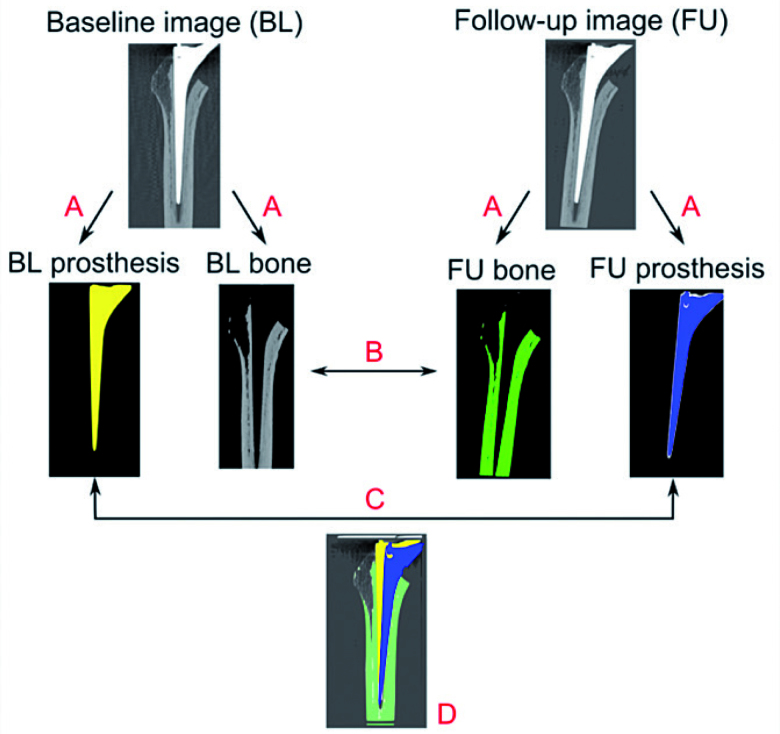

We used automated image analysis methods to estimate the migration of the femoral stem with respect to the proximal femur, between a baseline CT acquisition and a follow-up CT scan. First, the dataset was cropped manually to include only femoral elements, excluding the pelvis. Then the prosthesis and bone were segmented from the CT image pair. Next, using registration techniques, we determined the spatial transformations that aligned the respective objects. The migration can be found through comparison of both transformations (Polfliet et al. 2015, see Supplementary data) and by taking a standard reference system into account (Figure 1). Details of the segmentation, the registration, and the choice of a coordinate system are provided in Supplementary data.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed method. A. Segmentation of the bone and prosthesis images based on the source images. B. Bone registration. C. Prosthesis registration. D. Quantification of the migration and its visualization.

Output parameters

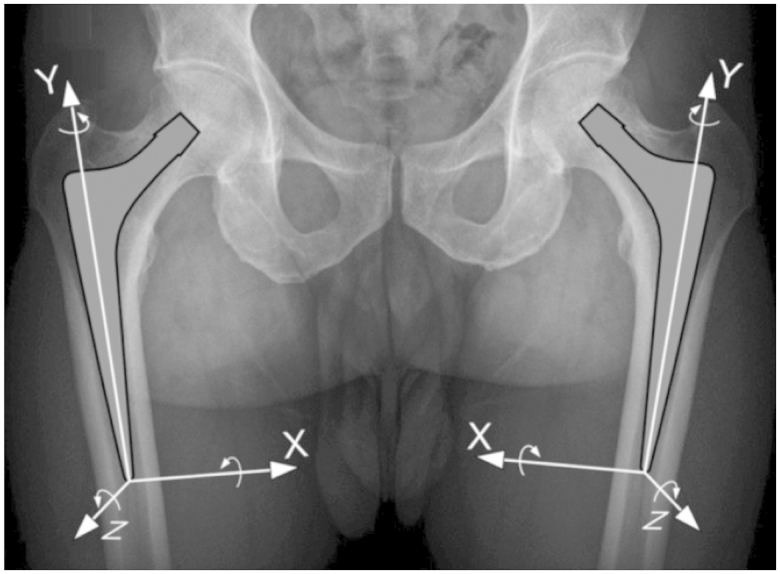

The stem-bone migration is expressed as 6 parameters representing the 6 degrees of freedom in a standardized coordinate system, i.e. 3 translations along the X-, Y-, and Z-axes and 3 rotations about these axes. Translations and rotations are presented using the anatomical nomenclature. Translations in the positive X-direction were considered to be medial displacement, positive values along the Y-axis to be superior displacement, and positive values along the Z-axis to be anterior displacement. Positive rotations about the X-axis were defined as anterior tilt or flexion, those about the Y-axis as internal rotation, endorotation, or retroversion, and those about the Z-axis as adduction or valgus. The decomposition sequence of rotation was XYZ, meaning that the first rotation took place about the X-axis, the second one about the Y-axis, and the last one about the Z-axis. To allow an easier comparison, the signs of the lateral-medial translation (along the X-axis), of the internal rotation (about the Y-axis), and of the adduction (about the Z-axis) were opposite for left and right hips (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Translations and rotations are expressed based on a coordinate system with the tip of the prosthesis as origin. Positive translations along the X-axis correspond to medial migration, those along the Y-axis to proximal migration, and those along the Z-axis to anterior migration. Positive rotations about the X-axis correspond to anterior tilt, those about the Y-axis to retroversion, and those about the Z-axis to valgus.

Based on the 6 migration parameters, the movement of each pixel allocated to the stem was calculated and the point of maximal stem migration was identified. The amount of maximal migration corresponds to the maximal total point motion measured with RSA (Valstar et al. 2005), but it incorporates all points of the stem and is not dependent on marker localization or migration.

Evaluation of accuracy and precision in the mechanical model

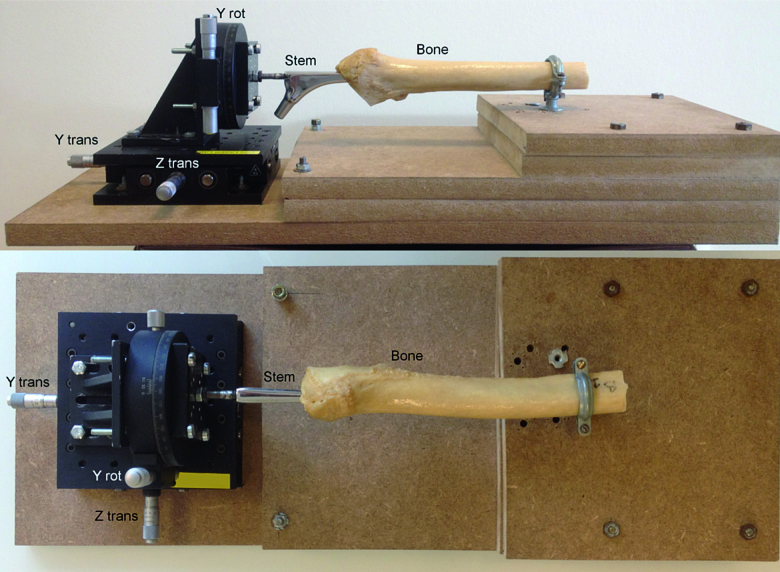

To evaluate the accuracy (Valstar et al. 2005) of CTSA, we compared our measurements to a controlled displacement of the stem within the cement mantle as described by Önsten et al. (2001). After removing the CPT stem from its cement mantle, the femoral component was rigidly fixed with a threaded bar to a 90-mm rotation stage (Melles Griot, Albuquerque, NM) and an XY translation stage equipped with 2 SM-13 vernier micrometers (Newport, Irvine, CA). The rotation stage had a vernier scale of 5 arcmin. The resolution of both translation stages was better than 3 µm and the translation micrometers had a vernier scale of 1.0 µm. The stem attached to the positioning stages and the femur containing the cement mantle were rigidly fixed to a wooden construct. The implant could move freely in 2 perpendicular planes and about the longitudinal axis of the stem (Figure 3). The specimen was CT-scanned along its longitudinal axis.

Figure 3.

To determine accuracy, a CPT hip implant (Stem) was cemented in a proximal femur (Bone) and removed from the cement mantle. The bone was fixed to a wooden board and the stem was fixed to 3 stages, allowing movement of the stem in controlled steps along the Y- and Z-axes (translation) and about the Y-axis (rotation). To assess translations along the X-axis, the bone and stem were rotated 90° about the Y-axis and the “Z-stage” was used to translate the stem in a mediolateral direction.

Single stem-specimen translations and rotations were measured along the X-, Y-, and Z-axes, and about the Y-axis. The combinations of a translation and rotation were measured along and about the Y-axis, whereas combined translations were investigated along the X-Y and Z-Y axes (Table 1). 40 CT scans were acquired: 1 at a zero position, 24 with translations (10 along the Y-axis, 7 along the X-axis, and 7 along Z-axis), 6 with rotations about the Y-axis and 9 with combined migrations. The position of the specimen within the CT scanner was altered between each scan to simulate a clinical setting.

Table 1.

Overview of the 39 comparisons between the baseline CT scanner and different degrees of translations and rotations used to assess the accuracy of the CTSA tool. Values are number

| Pure translations | X-axis | Y-axis | Z-axis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 mm to 0.5 mm (every 0.1 mm) | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1.0 mm and 1.5 mm | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2.0 mm, 3.0 mm, and 4.0 mm | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Pure rotations | ||||

| 0.5° to 3.0° (every 0.5°) | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| Combined translations and rotations | ||||

| 0.5 mm/0.5° to 1.5 mm/1.5° (every 0.5 mm and 0.5°) | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Combined translations | X- and | Y- and | ||

| Y-axes | Z-axes | |||

| 0.5 mm/0.5 mm to 1.5 mm/1.5 mm (every 0.5 mm and 0.5 mm) | 3 | 3 | ||

To determine the precision or repeatability of the CTSA technique, we measured the accuracy of zero-migration between the stem and the bone-cement complex (Valstar et al. 2005). Zero-migration was measured on 20 comparisons in 3 different settings with increasing difficulty of reproduction. First of all, the specimen was scanned 5 times in a fixed and centered position, allowing 4 comparisons. Secondly, the specimen was scanned 9 times in an off-centered position, allowing 8 comparisons, and the position of the specimen was altered between each scan. Finally, we measured zero-migration on 2 consecutive scans where we altered the position of the stem within the specimen and brought it back to its original position, and where we also modified the position of the specimen within the CT scanner. In this last experiment, 8 pairs of scans were compared, 2 after translations in each of the 3 planes and 2 after rotations about the Y-axis.

Evaluation of precision in patients

To determine the precision of the method in clinical practice, we analyzed 2 consecutive CT scans that were performed for medical reasons in 5 patients with no evidence of stem migration. As for the mechanical phantom, we compared the calculated stem-bone displacement to zero-migration. All 10 datasets were acquired using a Somatom Sensation 16 spiral CT scanner (Siemens AG) with the following settings: beam collimation 20 × 6 mm, mean tube current 239 (SD 109) mAs, mean tube potential 130 (SD 17) kVp, pitch 0.6 in one patient and 0.8 in 4 patients, mean pixel spacing 0.31 (SD 0.17) mm and mean field of view 134 (SD 38) mm. In total, 7 datasets were reconstructed based on the B80s filter and 3 based on the B60s filter. The mean reconstructed slice thickness was 0.67 (SD 0.13) mm and the mean increment was 0.36 (SD 0.10) mm. For one CT acquisition, the mean CTDIvol, mean DLP, and mean ED were 21.4 (SD 5.6) mGy, 530 (SD 161) mGy·cm, and 5.5 (SD 1.5) mSv, respectively.

Statistics

To determine the accuracy of CTSA, we calculated the mean values and standard deviations of the difference between the imposed (Di) and measured (Dm) displacement, i.e. the signed errors (MSE = mean(Di − Dm), SDSE = SD(Dm − Di)). The 95% TIs, with a confidence level set at 99%, were calculated as suggested by Wang et al. (2007). We also calculated the means and standard deviations of the absolute errors (MAE = mean(abs(Di − Dm), SDAE = SD(abs(Dm − Di)) and report the maximal absolute error (MaxAE) and the reliability coefficient (Portney and Watkins 2000) (rxx = SD(Di)/SD(Dm)).

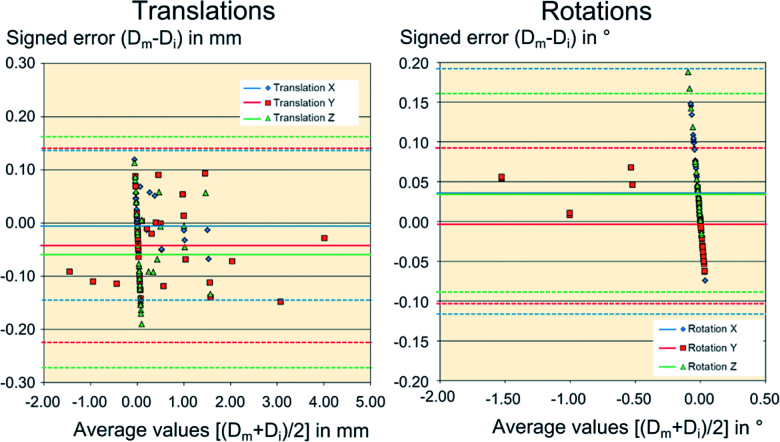

To express the accuracy of CTSA graphically, we plotted the average of the imposed and measurement migration ((Dm + Di)/2) on the X-axis against the signed error (Dm − Di) on the Y-axis, as described by Bland and Altman (1986). In that plot, the MSE and 95% TIs as calculated above were represented as horizontal lines.

To relate the imposed and measured displacements, we used a linear regression analysis. This approach was proposed by Önsten et al (2001) and allows estimation of the coefficient of determination (r2), the slope (m), and the intercept (b). The normality of data was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test and p-values are reported (p-SW).

The precision or reproducibility of the CTSA technique was calculated in a similar way, but the imposed displacement (Di) was set to zero. Statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel and the Real Statistics Resource Pack software, release 3.2.1 (Charles Zaiontz, www.real-statistics.com).

Results

Accuracy of the CTSA technique in a mechanical model

The accuracy of the CTSA technique in a mechanical model was evaluated by comparing imposed stem-bone motion and measured migration in 39 comparisons (Table 2). For translations, the mean signed error had a magnitude that was inferior to 0.06 mm with limits of the 95% TIs inferior to 0.28 mm in any direction. For rotations, the mean signed error was inferior to 0.04° with limits of the 95% tolerance interval inferior to 0.20° in any direction (Figure 4). The means of the absolute errors in translations and rotations were all inferior to 0.06 mm and 0.09°. In all cases, the differences between the imposed and the measured stem-bone motions did not exceed 0.20 mm for translations and 0.19° for rotations.

Table 2.

The accuracy of the CTSA tool for imposed migrations in the mechanical model, assessed for 39 comparisons

| MSE | SDSE | 95% TI | p-SW | MAE | SDAE | MaxAE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediolateral translation (X-axis) in mm | –0.004 | 0.053 | −0.147; 0.139 | 0.106 | 0.053 | 0.043 | 0.119 |

| Superoinferior translation (Y-axis) in mm | –0.042 | 0.068 | −0.224; 0.141 | 0.179 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 0.148 |

| Anteroposterior translation (Z-axis) in mm | –0.054 | 0.081 | −0.271; 0.163 | 0.000 a | 0.040 | 0.045 | 0.190 |

| Anteroposterior tilt (around X-axis) in ° | 0.038 | 0.057 | −0.117; 0.192 | 0.596 | 0.042 | 0.032 | 0.148 |

| Retro- and anteversion tilt (around Y-axis) in ° | –0.006 | 0.036 | −0.103; 0.091 | 0.085 | 0.064 | 0.047 | 0.068 |

| Varus-valgus tilt (around Z-axis) in ° | 0.038 | 0.047 | −0.087; 0.163 | 0.230 | 0.081 | 0.052 | 0.188 |

p < 0.05, the signed error data are not likely to be normally distributed.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plot of translations (left panel) and rotations (right panel) of the CTSA tool in the mechanical model. Horizontal lines refer to average values of the signed error for X-, Y-, and Z-translations and rotations (solid lines) and their 95% tolerance intervals (dotted lines).

In an ideal situation, the reliability coefficients for translations in the 3 planes and for rotations about the Y-axis would be 1. We found values superior to 0.96. Based on a linear regression relating imposed and measured displacements, we found coefficients of determination superior to 0.95, compared to 1 in an ideal situation. Also, the slopes and intercepts were all close to the ideal values of 1 and 0 respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

The reliability coefficients and the parameters of the linear regression of the accuracy of the CTSA tool in the mechanical model, assessed for 39 comparisons

| rxx | r2 | Slope (m) | Intercept (b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediolateral translation (X-axis) | 0.968 | 0.984 | 0.960 | 0.004 |

| Superoinferior translation (Y-axis) | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.996 | −0.040 |

| Anteroposterior translation (Z-axis) | 1.007 | 0.959 | 0.986 | −0.051 |

| Retro- and anteversion tilt (about Y-axis) | 0.973 | 0.999 | 0.972 | −0.016 |

Precision of the CTSA technique in a mechanical model

The precision of the CTSA technique in a mechanical model was evaluated by assessing the accuracy with which the absence of stem-bone motion was retrieved in 20 comparisons. The precision deteriorated progressively for more challenging configurations. For specimens scanned in a fixed/centered position, the precision was excellent (4 comparisons, MAE inferior to 0.006 mm and 0.004°, SDSE inferior to 0.005 mm and 0.005°, largest displacement of the point of maximal migration (PMM) 0.012 mm). For specimens scanned in a changing/off-centered position, the precision was somewhat inferior (8 comparisons, magnitude of the MAE inferior to 0.031 mm and 0.035°, SDSE inferior to 0.013 mm and 0.021°, largest displacement of the PMM 0.066 mm). For specimens scanned in a changing/off-centered position and in which the stem-bone location was altered but restored between scans, the precision worsened but remained satisfactory (8 comparisons, MAE inferior to 0.053 mm and 0.027°, SDSE inferior to 0.064 mm and 0.032°, largest displacement of the PMM 0.169 mm). As the changing/off-centered scenario is the most clinically relevant, we report those results in detail (Table 4).

Precision of the CTSA technique in patients

The in vivo precision of CTSA was assessed in consecutive CT scans of 5 total hip arthroplasty patients, with no evidence of migration between scans. Compared to the in vitro situation, the precision in patients was reduced (5 comparisons, MAE below 0.189 mm and 0.234°, SDSE below 0.203 mm and 0.279°, largest displacement of the PMM 0.972 mm). The poorest results were found when the resolution of at least 1 CT scan was suboptimal (slice thickness >0.6 mm and/or field of view >115 mm). In optimal circumstances, the precision was much better (2 comparisons, MAE inferior to 0.040 mm and 0.111°, SDSE inferior to 0.054 mm and 0.157°, largest displacement of the PMM 0.156 mm).

Discussion

We developed and validated a new marker-free CT scan-based spatial analysis tool (CTSA) to evaluate the relative displacement of a hip arthroplasty stem and the bone-cement complex. In an experimental setting, the limits of the 95% tolerance interval for accuracy did not exceed 0.28 mm for translations and 0.20° for rotations. The limits of the 95% tolerance interval for precision did not exceed 0.09 mm and 0.14°. These values are within the reported range for RSA techniques (<0.1 to 0.7 mm for translations and 0.03° to 0.5° for rotations (Ryd 1986, Snorrason and Kärrholm 1990, Önsten et al. 1995, Kärrholm et al. 1997, Østgaard et al. 1997, Önsten et al. 2001)). Yet, CTSA does not rely on bone/implant markers and offers the user-friendliness of EBRA but with more accuracy. As CT scans are readily available, CTSA does not require major initial investments. Postoperative CT scans could be used as reference, but CTSA might even be valuable to investigate symptomatic implants without initial CT scan. Indeed, implant loosening could be demonstrated either by comparing scans performed under rotational/longitudinal stresses, as with RSA (Mjöberg et al. 1984), or by comparing datasets taken during follow-up. Detection of inducible displacement provides an immediate answer, but clinical trials are needed to demonstrate reliability.

Compared to RSA (Valstar et al. 2005, Beardsley et al. 2007), CTSA uses a more reliable coordinate system that does not depend on bone alignment within a calibration box. With CTSA, the coordinate system to describe stem migration is based on the implant itself, but can be modified manually without any effect on the magnitude of the measured migration. This makes the technique independent of patient positioning during scanning and allows an accurate comparison of migration patterns between subjects and implants. On the other hand, CT scanning exposes patients to higher radiation doses (3.1 to 8.2 mSv) than RSA (0.15 mSv, Valstar 2001) or standard hip radiographs (0.28 mSv, Valstar 2001). The CT radiation doses in our study were comparable to reported standard values (DLP 550 mGy·cm and ED 7.3 mSv (Alheno 2014)). Nevertheless, radiation exposure from CT remains a concern and further dose optimization should be investigated, especially with the benefit of technical developments such as the distribution of iterative reconstruction algorithms (Gervaise et al. 2013). Meanwhile, CTSA might be less appropriate to evaluate hip implants in asymptomatic patients who would not benefit directly from the technique.

Although the initial results obtained with CTSA are promising, the present study and the technique itself have some limitations. First of all, CTSA was only fully validated in an experimental setting, with one implant type and without soft tissue interference. Precision, but not accuracy, was evaluated in a limited number of patients; this indicated that it could be used in clinical practice. Although statistics on such low numbers of comparisons are of limited value, precision in vivo appeared to be inferior when compared to the experimental setting, particularly if the quality of the CT scan was suboptimal. This will need further investigation in a larger number of patients. Another possible explanation for the inferior in vivo results could be the presence of motion artifacts. Accurate patient immobilization during CT scanning may be crucial, although it takes less than 30 seconds. Moreover, the applicability of CTSA in vivo in the presence of different implant shapes, volumes, and materials remains to be demonstrated. Especially large metallic implants (revision stems) may be more difficult to deal with due to artifacts during CT scanning. Secondly, the technique assumes rigid body displacement but does not take into account possible changes in the shape of the bone (ectopic calcifications, osteophytes, bone resorption, periprosthetic fractures) or density of the bone (stress shielding, progression of osteoporosis). This might interfere with the accuracy of the technique when used for long-term follow-up studies. On the other hand, and in contrast to RSA (Ryd 1986, Kaptein et al. 2005), CTSA is not sensitive to marker migration or occlusion.

In conclusion, CTSA has an accuracy and precision comparable to that of RSA and is a promising marker-free technique for evaluation of stem migration. We believe that it may be applicable to most patients, making it a powerful tool in clinical practice. With the development of a practical visual interface, it could become part of the routine evaluation of symptomatic hip arthroplasties.

Supplementary data

Details of the automated analysis of CT scan images are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8978.

TS, MP, and JV designed the study, gathered and analyzed the data, and performed the statistical analysis. GVG and NB optimized the CT scan settings, gathered and analyzed the data, and calculated the radiation doses. MP, RD, and JV developed the image-processing software. All the authors contributed to drafting and critical review of the paper.

This study was funded by the Department of Orthopedics of the Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel and the Department of Electronics and Informatics of Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). The Department of Radiology of the Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel provided free access to CT scan facilities. We are grateful to Professor Ronald Buyl, Department of Biostatistics and Information Technology of VUB, for his advice on statistical issues, to Doctor Werner Vandermeiren for helping with the construction of the mechanical phantom, and to Miss Loulia Leclercq for helping with CT scanning and visualization software.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Alheno I. Medical radiation exposure of the European population. Radiation Protection Report 180. European Commission, Luxemburg 2014.

- Alfaro-Adrian J, Gill H S, Marks B E, Murray D W. Mid-term migration of a cemented total hip replacement assessed by radiostereometric analysis. Int Orthop 1999; 23 (3): 140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley C L, Paller D J, Peura G D, Brattbakk B, Beynnon B D. The effect of coordinate system choice and segment reference on RSA-based knee translation measures. J Biomech 2007; 40 (6): 1417-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulé P E, Krismer M, Mayrhofer P, Wanner S, Le Duff M, Mattesich M, Stoeckl B, Amstutz H C, Biedermann R. EBRA-FCA for measurement of migration of the femoral component in surface arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87 (5): 741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann R, Krismer M, Stöckl B, Mayrhofer P, Ornstein E, Franzén H. Accuracy of EBRA-FCA in the measurement of migration of femoral components of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (2): 266-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J M, Altman D G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1 (8476): 307-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M A R, Plante-Bordeneuve P. Early migration and late aseptic failure of proximal femoral prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994; 76 (3): 432-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervaise A, Teixeira P, Villanic N, Lecocq S, Louisa M, Blum A. CT dose optimisation and reduction in osteoarticular disease. Diagn Interv Imaging 2013; 94 (4): 371-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadouche M, Witvoet J, Porcher R, Meunier A, Sedel L, Nizard R. Hydroxyapatite-coated versus grit-blasted femoral stems: A prospective, randomised study using EBRA-FCA. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83 (7): 979-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptfleisch J, Glyn-Jones S, Beard D J, Gill H S, Murray D W. The premature failure of the Charnley Elite-Plus stem. A confirmation of RSA predictions. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (2): 179-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilchmann T, Eingartner C, Heger K, Weise K. Femoral subsidence assessment after hip replacement: an experimental study. Ups J Med Sci 2006; 111 (3): 361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein B L, Valstar E R, Stoel B C, Rozing P M, Reiber J H C. A new type of model-based Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis for solving the occluded marker problem. J Biomech 2005; 38 (11): 2330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J. Roentgen stereophotogrammetry. Review of orthopedic applications. Acta Orthop Scand 1989; 60 (4): 491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994; 76 (6): 912-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J, Herberts P, Hultmark P, Malchau H, Nivbrant B, Thanner J. Radiostereometry of hip prostheses: Review of methodology and clinical results. Clin Orthop 1997; 344: 94-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krismer M, Stöckl B, Fischer M, Bauer R, Mayrhofer P, Ogon M. Early migration predicts late aspetic failure of hip sockets. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (3): 422-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krismer M, Biedermann R, Stöckl B, Fischer M, Bauer R, Haid C. The prediction of failure of the stem in THR by measurement of early migration using EBRA-FCA. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (2): 273-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroell A, Beaulé P, Krismer M, Behensky H, Stoeckl B, Biedermann R. Aseptic stem loosening in primary THA: migration analysis of cemented and cementless fixation. Int Orthop 2009; 33 (6): 1501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Rohrl S M, Boe B, Nordsletten L. Comparison of two different Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) systems with markerless elementary geometrical shape modeling for the measurement of stem migration. Clin Biomech 2014; 29 (8): 950-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjöberg B, Hansson L I, Selvik G. Instability of total hip prostheses at rotational stress. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric study. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55 (5): 504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjöberg B, Brismar J, Hansson L I, Pettersson H, Selvik G, Önnerfält R. Definition of endoprosthetic loosening. Comparison of arthrography, scintigraphy and roentgen stereophotogrammetry in prosthetic hips. Acta Orthop Scand 1985; 56 (6): 469-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K G, Kärrholm J. RSA in the assessment of aseptic loosening. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (1): 1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Önsten I, Akesson K, Besjakov J, Obrant K J. Migration of the Charnley stem in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77 (1): 18-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Önsten I, Berzins A, Shott S, Sumner D R. Accuracy and precision of radiostereometric analysis in the measurement of THR femoral component translations: human and canine in vitro models. J Orthop Res 2001; 19 (6): 1162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østgaard S E, Gottlieb L, Toksvig-Larsen S, Lebech A, Talbot A, Lund B. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis using computer-based image-analysis. J Biomech 1997; 30 (9): 993-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N J, Stockley I, Wilkinson J M. Direct plain radiographic methods versus EBRA-Digital for measuring implant migration after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17 (7): 917-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney L G, Watkins M P.. Foundations of clinical research. Applications to practice. Prentice Hall Health, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L. Micromotion in knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand 1986; 57(Suppl 220): 3-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of prosthetic fixation in the hip and knee joints. Clin Orthop 1992; 276: 56-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerlinck T, Casteleyn P-P. Review article. The design features of cemented femoral hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (11): 1409-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerlinck T, de Mey J, Deklerck R. In vitro analysis of the cement mantle of femoral hip implants: development and validation of a CT-scan based measurement tool. J Orthop Res 2005; 24 (4): 698-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snorrason F, Kärrholm J. Early loosening of revision hip arthroplasty. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. J Arthroplasty 1990; 5: 217-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valstar E R. PhD thesis: Digital Roentgen Stereophotogrammetry: Development, validation, and clinical application. University of Leiden 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valstar E R, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Börlin N, Kärrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (4): 563-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Voort P, Pijls B G, Nieuwenhuijse M J, Jasper J, Fiocco M, Plevier J W, Middeldorp S, Valstar E R, Nelissen R G. Early subsidence of shape-closed hip arthroplasty stems is associated with late revision. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (5): 1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Germansderfer A, Harms J, Rathore A S. Using statistical analysis for setting process validation acceptance criteria for biotech products. Biotechnol Prog 2007; 23 (1): 55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]