Abstract

Background

Educating people with stroke about community-based exercise programs (CBEPs) is a recommended practice that physical therapists are well positioned to implement.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the provision of education about CBEPs to people with stroke, barriers to providing education, and preferences for resources to facilitate education among physical therapists in neurological practice.

Design

A cross-sectional e-survey of physical therapists treating adults with stroke in Ontario, Canada, was conducted.

Methods

A link to the questionnaire was emailed to physical therapists in a provincial stroke network, a provincial physical therapy association, and on hospital and previous research lists.

Results

Responses from 186 physical therapists were analyzed. The percentage of respondents who reported providing CBEP education was 84.4%. Only 36.6% reported typically providing education to ≥7 out of 10 patients with stroke. Physical (90.5%) and preventative (84.6%) health benefits of exercise were most frequently discussed. Therapists reported most commonly delivering education at discharge (73.7%). Most frequently cited barriers to educating patients were a perceived lack of suitable programs (53.2%) and a lack of awareness of local CBEPs (23.8%). Lists of CBEPs (94.1%) or brochures (94.1%) were considered to be facilitators. The percentage of physical therapists providing CBEP education varied across acute, rehabilitation, and public outpatient settings.

Limitations

The percentage of physical therapists providing education may have been overestimated if respondents who deliver CBEP education were more likely to participate and if participants answered in a socially desirable way.

Conclusions

Even though a high proportion of physical therapists provide CBEP education, education is not consistently delivered to the majority of patients poststroke. Although a CBEP list or brochure would facilitate education regarding existing CBEPs, efforts to implement CBEPs are needed to help overcome the lack of suitable programs.

Worldwide, 15 million people sustain a stroke each year.1 Stroke is a leading cause of disability, as 51% of people lose the ability to walk independently after stroke1,2 and 80% have sitting, stepping, and standing balance deficits.3 Such deficits contribute to reduced rates of physical activity among people living with stroke compared with the general population.4–6 Prolonged physical inactivity increases the risk of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and recurrent stroke.7,8 Health benefits of exercise for people living with stroke include improved balance, gait, cognition, mood, physical function, and health-related quality of life.9–13 To achieve these health benefits, current guidelines recommend that people with stroke participate in aerobic activity 3 to 5 days per week for 20 to 60 minutes per session and participate in resistance, flexibility, and neuromuscular training 2 to 3 days per week.14 Community-based exercise programs (CBEPs)15–19 can provide people with stroke with an opportunity to increase their physical activity levels. We have defined a CBEP as any program of physical activities that aims to promote health and well-being and that is accessible to people living in the community. Community-based exercise programs may be privately or publicly funded, and certain programs may require medical referral. As such, CBEPs represent a wide variety of programs and are not necessarily designed for the rehabilitation of people with stroke.

A wide range of CBEPs delivered by fitness instructors with the appropriate training are safe, feasible, and potentially effective in improving balance, mobility, and physical activity in people with stroke.16,19–23 Most reported programs, to date, include group task-oriented exercise targeting balance and mobility limitations and may include health care–recreation partnerships wherein exercise classes are delivered by fitness instructors who have been trained by physical therapists.16,19,20,22 Such classes take place in community centers run by municipal recreation divisions and nonprofit organizations such as the YMCA.16,19,20,22 In Canada, health care professionals also can refer people with stroke to cardiac rehabilitation programs that include aerobic and resistance training.24 Programs that incorporate strengthening, balance exercises, and hydrotherapy also have been reported.21,25

Exercise participation is recommended poststroke,14,26 as it is vital in maintaining health and preventing a second stroke. In Canada, best practice guidelines recommend that health care professionals assess readiness to exercise in people with stroke, provide them with an appropriate exercise program, and educate them regarding the availability and accessibility of community resources such as CBEPs.26 Physical therapists are qualified and appropriate health care professionals to provide education to people with stroke on the appropriateness and availability of CBEPs.27–30 Physical therapists play a primary role in prescribing and overseeing exercise to improve balance, gait, and mobility poststroke.18–20,30 Individuals with neurological conditions also report having increased confidence in their exercise sessions when supported by a physical therapist,31 making them likely to value physical therapists' recommendations regarding CBEPs.

To date, there are no studies examining physical therapist practice in educating people with stroke on CBEPs. This is an important area to investigate, as it can help to identify a knowledge-to-practice gap that can be addressed through adaptations to practice and health policies and through the provision of appropriate resources and training. Some studies have investigated the extent to which physical therapists are implementing best practice assessment and treatment recommendations in a neurological population.32–34 Little is known, however, about the provision, nature, or timing of education that physical therapists provide regarding CBEPs to people with stroke.

To understand the implementation of recommended practices, it is vital to evaluate potential factors influencing clinician's behaviors.35 Factors influencing implementation of best practices poststroke include challenges related to practitioner characteristics, such as knowledge, attitudes, skill, and self-efficacy36–38; patient characteristics, such as stroke severity39; and organizational characteristics, such as available time and educational resources.37 Factors influencing provision of education have not been examined. As characteristics of best practice35 can influence clinical decision making, it is essential to examine the particular context of provision of education on CBEPs poststroke to understand the challenges physical therapists face. The literature also is lacking with respect to the type of educational resources that physical therapists prefer to use when providing information to people under their care. This information would inform efforts to facilitate physical therapists' implementation of guideline recommendations.26,35 It is of interest to explore when CBEP education occurs across the continuum of care, as this education should not be limited to a particular practice setting but rather should be aligned with people's readiness and needs.26

The primary objectives of this study were: (1) to characterize the provision, nature, and timing of education provided to people with stroke regarding CBEPs among physical therapists and (2) to identify barriers to educating people with stroke about CBEPs and preferences for educational resources when providing CBEP education to people with stroke. A secondary objective was to determine whether the provision of education by physical therapists varies across practice settings. We hypothesized that the percentage of physical therapists providing education regarding CBEPs would vary across the acute, rehabilitation, and public outpatient practice settings.

Method

Study Design

A cross-sectional Web-based survey of physical therapists providing care to adults with stroke in Ontario, Canada, was conducted. A modified Dillman approach was used to maximize response rate. The Dillman method involves use of presurvey notification messages, multiple survey invitations and reminders, and incentives to optimize participation.40 The CHERRIES checklist for quality reporting of Web-based surveys was used to guide reporting.41

Participants

Physical therapists were eligible to participate if they were currently registered with the provincial regulatory body and treated adults 18 years of age or older who had sustained a stroke in their clinical practice. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and consent was implied through submission of a completed questionnaire.

Questionnaire Development

Fluid Surveys software (FluidSurveys, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was used to create a Web-based questionnaire that consisted of items within 4 domains designed to address the study objectives: (1) frequency of providing CBEP education, (2) nature and timing of CBEP education throughout the care continuum, (3) barriers to providing CBEP education, and (4) preferences for educational resources to facilitate CBEP education. To describe study participants and assess generalizability, an additional sociodemographic domain was developed using items from a previously validated survey questionnaire.33,36 Nine physical therapists who met the eligibility criteria evaluated the questionnaire for face and content validity and readability. These individuals practiced in acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, and public outpatient hospitals across rural, urban, and suburban settings. Minor improvements were made to the wording of items based on their feedback. Consultants reported an average completion time of 15 minutes, which approximates the completion time of 13 minutes found to optimize response rates in online surveys.42 The final 76-item questionnaire (eAppendix) includes domains pertaining to eligibility (2 items), provision (5 items), nature (19 items), and timing (3 items) of education regarding CBEPs; barriers to educating (24 items); preferences for resources (6 items); and sociodemographic and practice characteristics (17 items). If a participant answered “no” to either of the 2 eligibility questions, the survey was terminated.

The first item within provision of education was used to divide respondents into those who reported providing and not providing education regarding CBEPs to people with stroke. Only those respondents who answered “yes” completed questionnaire items related to provision, nature, and timing of education. For those who answered “no,” the questionnaire skipped to the section on barriers. One questionnaire item regarding provision of CBEP education asked respondents to indicate the number of patients with stroke out of 10 who they typically educated about CBEPs, with response options of 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 to 10. For the remaining questions within provision, nature, timing of CBEP education, and barriers related to patient factors, respondents answered using a 4-point ordinal scale with the following options: “none of the time,” “some of the time,” “most of the time,” and “all of the time.” In the event that respondents did not provide education on CBEPs because of shared responsibilities on the health care team, one questionnaire item inquired as to whether other health professionals provided education, with response options consisting of “yes,” “no,” and “not present.” For the barriers related to physical therapist factors and preferred resources, respondents reported their answers on a 5-point Likert scale with the following response options: “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree.” For selected variables, such as the type of CBEP, mode of education, and professional responsibility to educate, respondents could report additional “other” responses in a text box.

Sampling

Three recruitment strategies were used to optimize participation. The first strategy involved collaboration with the Ontario Stroke Network,43 which provides provincial leadership and coordination for the Ontario Stroke System (the 11 regional stroke networks consisting of a collaborative system of provider organizations and partners who deliver stroke care across the province and care continuum) and recommends and evaluates province-wide standards.26 Regional stroke network coordinators and hospital representatives were asked to forward recruitment emails to physical therapists within each region. The second strategy involved disseminating a recruitment notice in an electronic newsletter emailed to members of the provincial physical therapy association. The third strategy involved sending recruitment emails to 168 physical therapists who treat people with stroke and who had participated in a previous study36 and had provided permission to be contacted for future research.

Following a modified 5-step Dillman approach,40 a pre-notice email outlining the study was first sent out to all groups except members of the provincial physical therapy association, for whom the number of recruitment notices was limited to three. Two weeks following the pre-notice, the first invitation to participate in the study was sent, with a link to the questionnaire. Two reminder emails with a link to the questionnaire were subsequently sent at 2-week intervals. As an incentive to participate, all 3 invitations included information about an optional draw for one of two $25 gift cards. Within a week after the questionnaire deadline, a final thank-you email was sent.

Data Analysis

Data from the FluidSurveys software were exported into an Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) file and imported into IBM SPSS (version 21) software (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York) for statistical analysis. Questionnaires with less than 80% of items addressing study objectives completed were removed from the analysis. For all items with categorical response scales, the data were summarized using frequencies and percentages. For discussion purposes, the research team characterized percentages ≤25% as low, >25% to ≤50% as low to moderate, >50% to ≤75% as moderate, and >75% as high. For ease of reporting, the 5-point Likert scale response options of “strongly agree” and “agree” were collapsed to form “agree,” and response options of “strongly disagree” and “disagree” were combined to form “disagree.” Responses entered into text boxes were reviewed to identify categories and their respective frequencies were determined.

Prior to examining the association between the rate of education and practice setting, the response scale for rate of education was converted into a dichotomous scale that included a low-to-moderate rate (1–6/10 patients) and a high rate (7–10/10 patients) to ensure adequate cell counts. Similarly, when interpreting study findings, “consistent” provision of CBEP education was defined as typically providing education to at least 7 out of 10 patients with stroke. For practice setting, the response categories of outpatient general hospital, outpatient rehabilitation facility, and community care access center were combined to create the public outpatient category. The remaining practice setting categories were acute (inpatient general hospital) and rehabilitation (inpatient rehabilitation facility). The chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between the rate of education and the settings examined. An alpha level of .05 determined statistical significance.

Role of the Funding Source

This research was completed with funding from an Ontario Physiotherapy Association (OPA) Central Toronto District Student Research Grant. Dr Salbach holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and an Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher Award.

Results

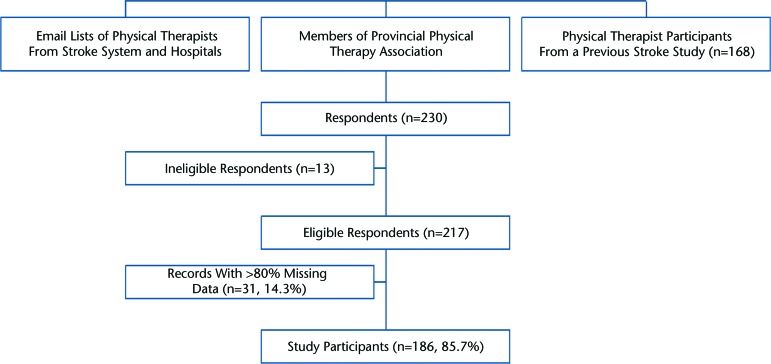

Of the 230 individuals who completed a questionnaire online, 13 were excluded because they were not registered with the provincial regulatory body (n=4) or were not currently treating adults with stroke (n=9). Of the 217 eligible respondents, 14.3% of records were removed due to missing data. Data from 186 participants were analyzed (Figure).

Figure.

Outcomes of recruitment.

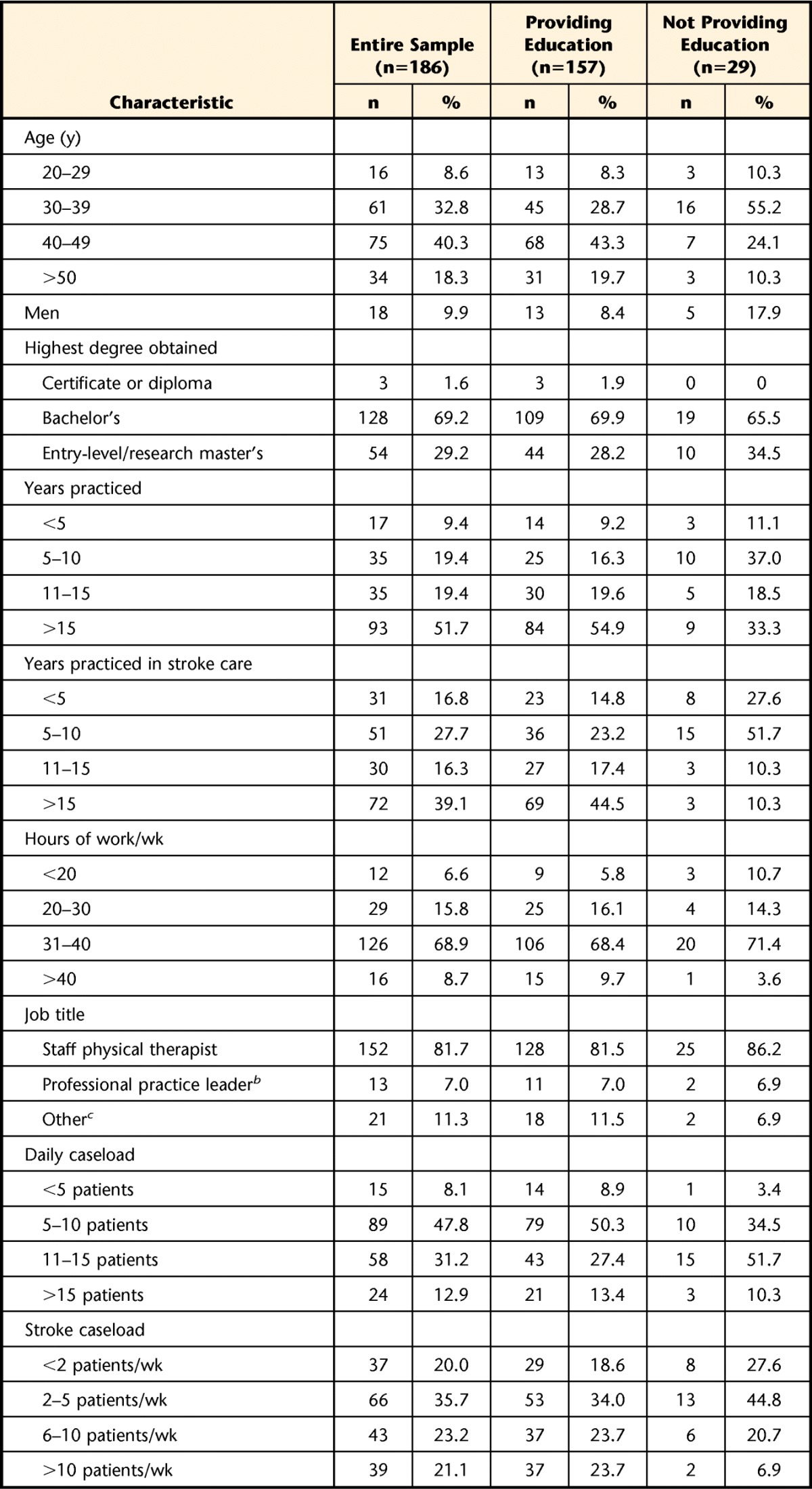

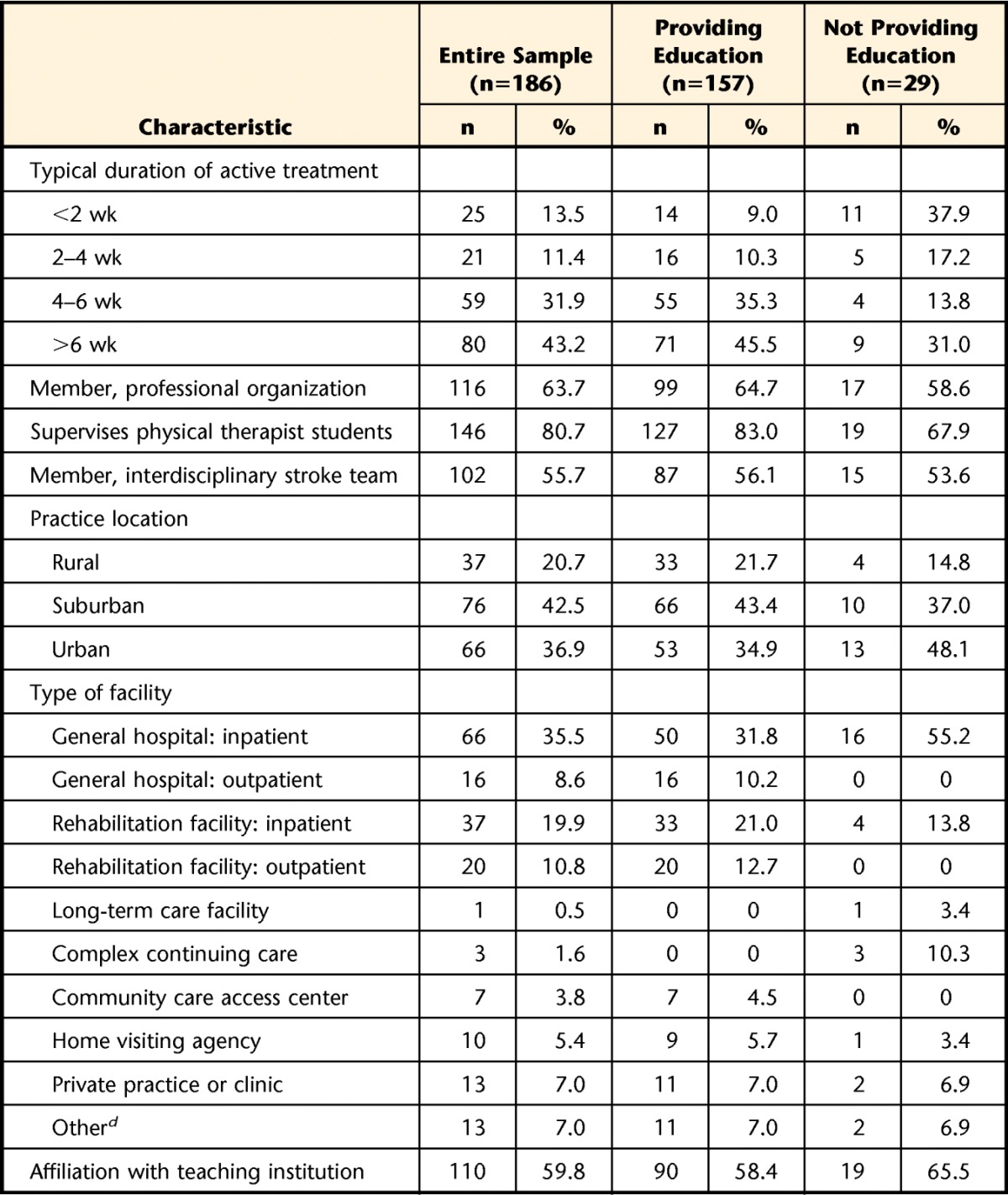

Table 1 presents respondent and practice characteristics for the entire study sample, as well as participants classified as providing (n=157, 84.4%) and not providing (n=29, 15.6%) education on CBEPs. In the entire sample, 73.1% respondents were 30 to 49 years of age, 69.2% held a bachelor's degree, and 55.7% practiced as part of an interdisciplinary stroke team. The most commonly reported practice settings were general hospital inpatient care (35.5%) and facilities in a suburban location (42.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents and Their Practice (n=186)a

Values may not add up to 186 secondary to missing values.

b Professional practice leader is defined as a staff member who supervises at least one other physical therapist and provides clinical or experiential expertise in their area of work.

c Examples of responses were private or independent contractors.

d Examples of responses were specialized hospitals, community stroke rehabilitation teams, and community centers.

Provision, Nature, and Timing of CBEP Education

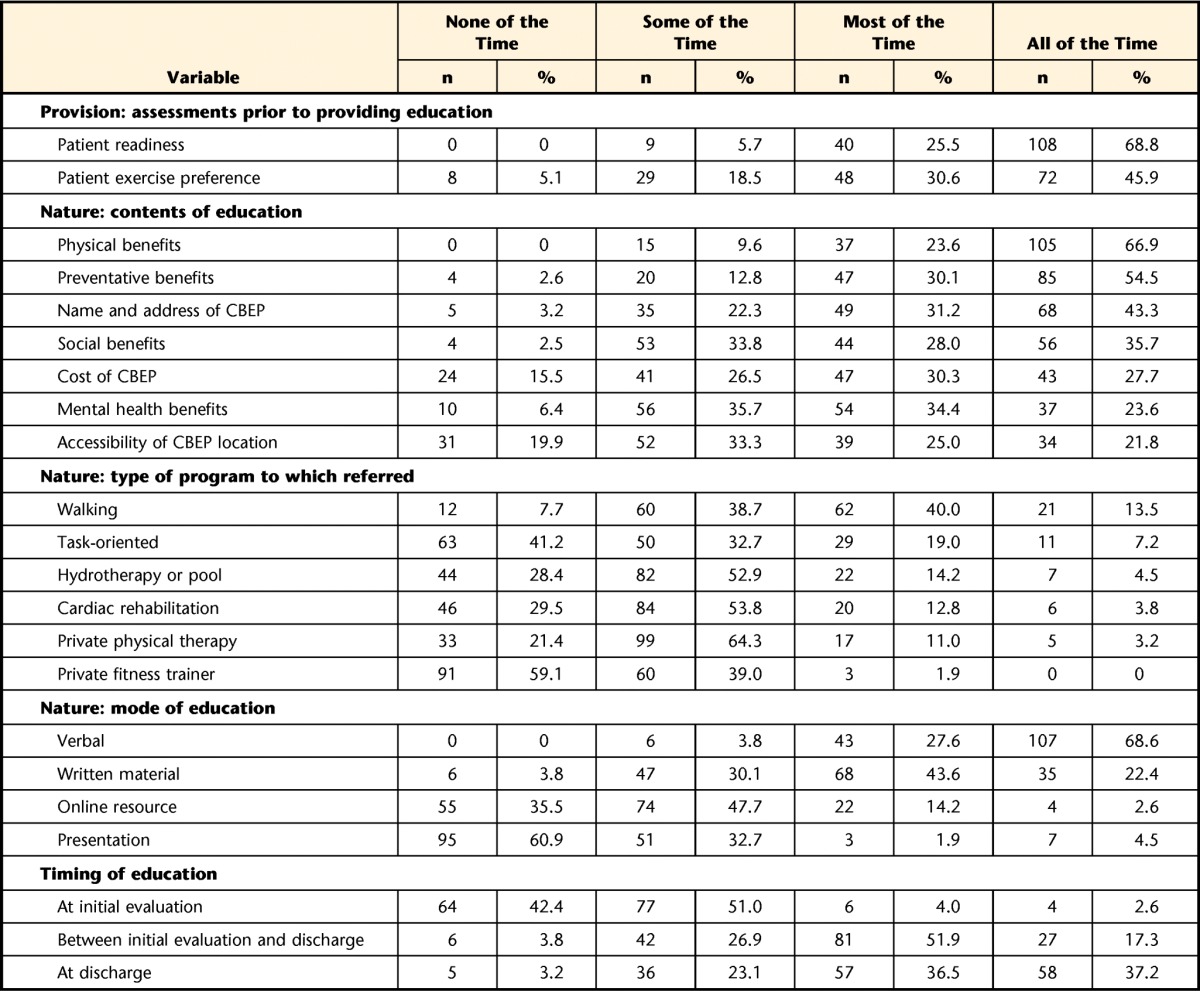

In the entire sample (n=186), the percentage of participants who reported typically providing education to 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 to 10 patients out of 10 patients with stroke was 16.7%, 29.6%, 17.2%, and 36.6%, respectively. Table 2 presents results related to the provision, nature, and timing of CBEP education.

Table 2.

Provision, Nature, and Timing of Education (n=157)a

CBEP=community-based exercise program.

Of the 157 respondents who reported providing CBEP education, 94.3% of physical therapists reported assessing patient readiness most or all of the time. When educating on CBEPs, respondents reported discussing the physical benefits (90.4%), preventative benefits (84.6%), names and addresses of exercise programs (74.5%), social benefits (63.7%), cost (58%), mental benefits (57.9%) and accessibility (46.8%) most or all of the time. The most commonly cited programs to which respondents reported referring patients most or all of the time were: walking programs (53.5%), task-oriented exercise programs (26.2%), hydrotherapy or pool programs (18.7%), and cardiac rehabilitation programs (16.6%). In the “other” category, physical therapists most commonly identified making referrals to tai chi (n=15, 9.6%) and group exercise programs (n=14, 8.9%). The mode of education with the highest reported use most or all of the time was verbal education (96.2%). In the “other” category, respondents most frequently identified site visits or tours (n=7, 4.5%) to be a preferred mode of education. Respondents most frequently cited discharge (69.2%) as the time point for when CBEP education took place most or all of the time.

Perceptions of Factors Influencing the Provision of CBEP Education (n=186)

A total of 93.0% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that physical therapists have the primary responsibility to provide education on CBEP. Physical therapists also were asked to report on whether they thought other health care professionals provided CBEP education. Respondents indicated that the following health care professionals provide education on CBEPs: physical therapist colleagues (93.5%), occupational therapists (68.0%), social workers (38.2%), physical therapist assistants (34.7%), speech-language pathologists (30.8%), physicians (30.2%), recreational therapists (30.1%), nurses (25.9%), kinesiologists (4.7%), and registered massage therapists (3.5%).

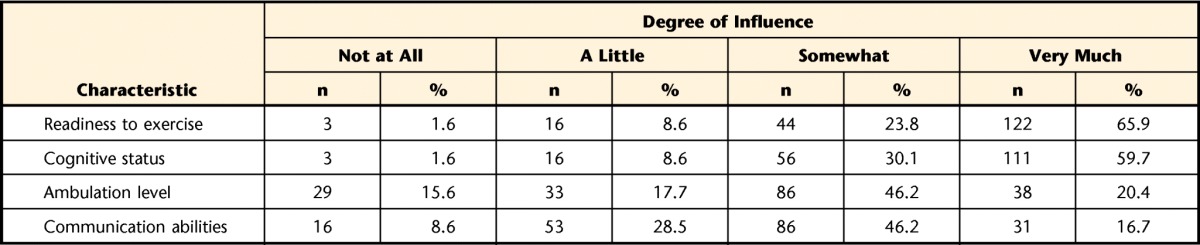

Table 3 presents therapists' perceptions of the extent to which patient characteristics influence their decision to provide CBEP education. The most frequently reported consideration prior to providing CBEP education was the patient's readiness to exercise (65.9%). In a comment box at the end of the questionnaire, respondents cited a lack of programs for patients who are nonambulatory or have a low level of walking ability (n=7, 3.8%) and a lack of stroke expertise of those running CBEPs (n=3, 1.6%) as additional factors.

Table 3.

Degree of Influence of Patient Characteristics on the Decision to Provide Education on Community-Based Exercise Programs (n=186)

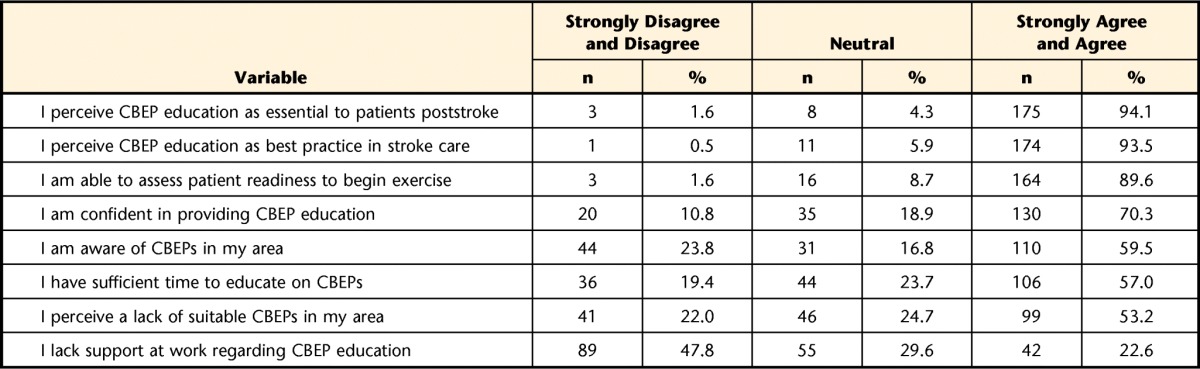

Table 4 presents physical therapists' attitudes and beliefs regarding personal and external factors influencing CBEP education. The percentage of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that CBEP education is essential and represents best practice was 94.1% and 93.5%, respectively. The percentage of therapists who perceived a lack of suitable CBEPs in their area or who personally lacked awareness of CBEPs in their area was 53.2% and 23.8%, respectively.

Table 4.

Practitioner Attitudes and Beliefs About Provision of CBEP Education (n=186)a

CBEP=community-based exercise program.

Preferences for Education Resources

In the entire sample (n=186), respondents agreed or strongly agreed that a list of CBEPs (94.1%), pamphlets or brochures on CBEPs (94.1%), a resource person (88.2%), education on assessing patient readiness for exercise (67.4%), and education on providing CBEP education (45.4%) would facilitate their provision of CBEP education. In the “other” category, 9 respondents (4.8%) identified that an accessible website that is regularly updated would be an ideal educational resource.

Rate of Education Across Practice Settings

Among 124 respondents who identified that they do educate on CBEP, the percentage of respondents providing a high rate of education in acute (n=49), rehabilitation (n=32), and public outpatient (n=43) settings was 20.4%, 25.0%, and 65.1%, respectively. A significant association between the rate of providing education and practice setting was observed (χ2 [2, n=124]=22.3, P<.001).

Discussion

This study aimed to describe the education regarding CBEPs that physical therapists provide to people with stroke, the perceived barriers to providing education, and preferences for resources to facilitate this education. Although a high proportion of physical therapists indicated that they provide CBEP education, only one-third consistently provided it to at least 7 out of 10 patients with stroke. Therapists appeared to prefer delivering education on CBEPs verbally between initial assessment and discharge, and at the time of discharge. Education predominantly included information on the physical and preventative benefits of exercise. Of the range of exercise programs available, physical therapists appear to most often refer people with stroke to walking, task-oriented, and hydrotherapy or pool programs. Almost all respondents agreed that physical therapists play a prominent role in providing education about CBEPs and that this is part of best practice. Nevertheless, physical therapists face challenges delivering this education. Primary considerations appear to be patient cognitive status, patient readiness for education, a lack of suitable programs, and a lack of awareness of available programs among therapists. The majority of therapists agreed that a list of CBEPs, pamphlets or brochures, and a resource person in the community would facilitate CBEP education. The provision of education was found to vary significantly across acute, rehabilitation, and public outpatient settings, as hypothesized.

When educating patients on CBEPs, therapists reported that they discuss the physical and preventative benefits of exercise to a greater degree than the social and mental benefits. This finding is not surprising, as a major focus of the best practice recommendations for stroke care is on the physical and preventative benefits of exercise.26 Given the positive impact of exercise in improving depression,44–47 social isolation,48 cognition and mood,49,50 and self-efficacy51 in people with stroke, physical therapists may want to tailor the education they provide to the particular physical, mental, and social needs of the individual with stroke.

The findings from this study suggest that physical therapists discuss certain program-specific information such as program name and location more often than accessibility and cost when providing education about CBEPs. It is possible that therapists prioritize the importance of the program name and location or that information about accessibility and cost is not readily available. It is part of best practice recommendations to educate people with stroke regarding availability and accessibility of community services and resources, including CBEPs.26 Moreover, a participant's lack of knowledge on these topics limits exercise participation.52 Therefore, it is important for physical therapists to convey information regarding the cost and accessibility of CBEPs to their patients.

Physical therapists appear to infrequently refer people with stroke to task-oriented exercise and cardiac rehabilitation programs. This finding is surprising, as literature supports the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of these programs for people with mild or moderate motor impairments after stroke.16,19 Moreover, task-oriented exercise programs offered in community centers for people with balance and mobility limitations are feasible to implement, as reflected by the emergence of programs in Ontario, Canada.19,53 Further research into the reason for a lack of referrals to these programs is needed.

Physical therapists reported providing education throughout the continuum of patient care, but most often at the time of discharge. Therefore, it is possible that physical therapists discuss CBEPs more than once. Findings also indicate that the percentage of physical therapists providing CBEP education to 7 to 10 out of 10 patients varies across the acute, rehabilitation, and public outpatient settings. Education should not be specific to a certain time or practice setting, but rather should depend on when the patient appears ready to receive this information.14 More than half of the respondents reported assessing readiness prior to educating on CBEPs, and almost all physical therapists reported feeling confident in their ability to assess patient readiness to exercise. Still, two-thirds of participants reported that they would like further information about how to assess patient readiness. These findings will inform professional development activities and future research.

The findings highlight a number of barriers that may be responsible for the lack of consistent delivery of education regarding CBEPs among two-thirds of therapists. A perceived lack of suitable CBEPs is a major barrier, which aligns with previous research.54 Although there is evidence of increasing availability of exercise programs for people with stroke,19,24,53 these programs are more readily available in urban than rural communities.54 The findings also show that physical therapists perceive that existing programs are ill-suited to the abilities of the individuals in their caseload, particularly patients who are nonambulatory or have a low level of walking ability. For example, requirements to participate in a task-oriented program include the ability to ambulate 10 m independently, with or without a mobility aid.19 Selected participants also perceive that program instructors lack expertise, a finding noted elsewhere.31,52 Lastly, physical therapists may not know of programs that exist in their communities, as almost a quarter of those surveyed indicated that they are unaware of CBEPs in their area. An important implication for future physical therapist practice is that resources need to be developed to increase physical therapists' awareness of local CBEPs.

Participants preferred a resource person in the community who patients could contact. This is a responsibility that could be undertaken by health professionals in existing community roles (eg, community health navigator55). Such an individual could serve as a centralized resource and take responsibility for compiling a list of community exercise programs suitable for people with disability. Such programs should require some level of accreditation56 or involvement from a health care professional53 to ensure the safety, feasibility, and quality of the programs. Programs could be added to existing websites57 to enable easy access to program information. A strategy combining the use of physical resources (eg, pamphlets and resource contacts) and Web-based contents (eg, websites, programs, modules) may best be able to capture and inform the largest target audience, regardless of whether it be physical therapists or people with stroke.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several limitations. It was impossible to determine a survey response rate given the use of multiple recruitment strategies, combined with a lack of published data regarding the number of physical therapists working with a stroke population in Ontario. The provincial regulatory body indicates that 439 physical therapists are currently working in adult neurological practice (Ann Marie Humber, email; November 22, 2013). This number would translate to a response rate of 52.4%, which is high compared with other Web-based surveys.42 Although a high number of respondents were from southern Ontario, representation was obtained from each provincial stroke region, and the sociodemographic profiles of respondents are similar to those of other studies that have involved physical therapists working with a stroke population.33 Therefore, it is probable that the study sample is representative of physical therapists providing services to people with stroke in Ontario. Results are likely applicable to other provinces in Canada due to the existence of a national stroke strategy26 and similarities in physical therapy curricula across provinces.28

Physical therapists who participated in the survey may have been more interested and engaged in providing CBEP education than those who did not participate. Additionally, participants may have responded to questions regarding their clinical practice in a socially desirable way,58 even though questionnaire items were carefully framed to avoid a judgmental tone. These biases would have led to an overestimation of the percentage of physical therapists who report providing education.

In conclusion, although a high proportion of physical therapists agree with the importance of providing CBEP education to patients after stroke, the majority of physical therapists do not consistently provide this education. The primary factors influencing therapists' provision of CBEP education include a perceived lack of suitable local programs and a lack of awareness and knowledge among therapists of available programs. Education can be facilitated by increasing the availability of physical therapists' preferred resources, which include a list of available CBEPs, brochures on CBEPs, and a resource person in the community who patients can contact. Findings can be used to increase understanding of the factors influencing education on CBEPs, inform future physical therapist training, and promote the development of appropriate educational resources. Future research should examine how to appropriately evaluate patient readiness to exercise informed by the Transtheoretical Model of Change, the effect of different resources and educational strategies depending on the level of readiness to exercise, and how to optimize coordination of CBEP education across practice settings. This research would inform the development of an approach to providing CBEP education that is tailored to the individual.

Footnotes

Ms Lau, Ms Chitussi, Ms Elliott, Ms Giannone, Ms McMahon, Dr Sibley, and Dr Salbach provided concept/idea/research design, writing, and data analysis. Ms Lau, Ms Chitussi, Ms Elliott, Ms Giannone, Ms McMahon, and Dr Salbach provided data collection. Ms Lau, Ms Chitussi, Ms McMahon, and Dr Salbach provided project management. Dr Salbach provided fund procurement and facilities/equipment. Ms Tee, Ms Matthews, and Dr Salbach provided institutional liaisons. Ms Chitussi, Ms McMahon, Ms Tee, Ms Matthews, and Dr Salbach provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The University of Toronto Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol.

For Ms Lau, Ms Chitussi, Ms Elliot, Ms Giannone, and Ms McMahon, this research was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a MScPT degree at the University of Toronto with funding from an Ontario Physiotherapy Association (OPA) Central Toronto District Student Research Grant. The authors acknowledge the OPA and the Ontario Stroke Network for assistance with recruitment. Dr Salbach holds a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and an Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher Award.

References

- 1. World Stroke Organization. World stroke campaign. Available at: http://www.world-stroke.org/advocacy/world-stroke-campaign Accessed May 26, 2014.

- 2. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tyson SF, Hanley M, Chillala J, et al. Balance disability after stroke. Phys Ther. 2006;86:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health & Human Services: The Surgeon General's call to action to improve the health and wellness of persons with disabilities. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44667/ Accessed October 28, 2015.

- 5. Rimmer JH, Rubin SS, Braddock D, Hedman G. Physical activity patterns of African-American women with physical disabilities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Michael KM, Allen JK, Macko RF. Reduced ambulatory activity after stroke: the role of balance, gait, and cardiovascular fitness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1552–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Warburton DE, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada's Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paterson DH, Warburton DE. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: a systematic review related to Canada's Physical Activity Guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lubetzky-Vilnai A, Kartin D. The effect of balance training on balance performance in individuals poststroke: a systematic review. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010;34:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wevers L, van de Port I, Vermue M, et al. Effects of task-oriented circuit class training on walking competency after stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40:2450–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia-Soto E, Lopez de Munain ML, Santibanez M. Effects of combined aerobic and resistance training on cognition following stroke: a systematic review. Rev Neurol. 2013;57:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ada L, Dorsch S, Canning CG. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pang MY, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, Gylfadottir S. The use of aerobic exercise training in improving aerobic capacity in individuals with stroke: a meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2014;45:2532–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eng JJ, Chu KS, Kim CM, et al. A community-based group exercise program for persons with chronic stroke. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1271–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuart M, Benvenuti F, Macko R, et al. Community-based adaptive physical activity program for chronic stroke: feasibility, safety, and efficacy of the empoli model. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:726–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marigold DS, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, et al. Exercise leads to faster postural reflexes, improved balance and mobility, and fewer falls in older persons with chronic stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pang MY, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, et al. A community-based fitness and mobility exercise program for older adults with chronic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1667–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salbach NM, Howe JA, Brunton K, et al. Partnering to increase access to community exercise programs for people with stroke, acquired brain injury and multiple sclerosis. J Phys Act Health 2014;11:838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrington R, Taylor G, Hollinghurst S, et al. A community-based exercise and education scheme for stroke survivors: a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sims J, Galea M, Taylor N, et al. Regenerate: assessing the feasibility of a strength-training program to enhance the physical and mental health of chronic post stroke patients with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cramp MC, Greenwood RJ, Gill M, et al. Effectiveness of a community-based low-intensity exercise programme for ambulatory stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kilbride C, Norris M, Theis N, Mohagheghi AA. Action for Rehabilitation from Neurological Injury (ARNI): a pragmatic study of functional training for stroke survivors. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2013;1:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marzolini S, McIlroy W, Oh P, Brooks D. Can individuals participating in cardiac rehabilitation achieve recommended exercise training levels following stroke? J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012;32:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noh DK, Lim JY, Shin HI, Paik NJ. The effect of aquatic therapy on postural balance and muscle strength in stroke survivors: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, et al. ; on behalf of the Canadian Stroke Best Practices Advisory Committee and Writing Groups. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations Overview and Methodology. 5th ed Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Heart and Stroke Foundation, Canada; 2014. Available at: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/ Accessed August 29, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Policy statement: physical therapists as exercise experts across the life span. Available at: http://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-exercise%20experts Accessed August 29, 2013.

- 28. Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs. Entry-to-practice physiotherapy curriculum: content guidelines for Canadian university program. Available at: http://www.physiotherapyeducation.ca/PhysiotherapyEducation.html Accessed August 29, 2013.

- 29. Canadian Physiotherapy Association. 2012 description of physiotherapy in Canada. Available at: http://www.physiotherapy.ca/getmedia/e3f53048-d8e0-416b-9c9d-38277c0e6643/DoPEN(final).pdf.aspx Accessed August 29, 2013.

- 30. Stevenson TJ. Detecting change in patients with stroke using the berg balance scale. Aust J Physiother. 2001;47:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elsworth C, Dawes H, Sackley C, et al. A study of perceived facilitators to physical activity in neurological conditions. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16:17. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van Peppen RP, Maissan FJ, Van Genderen FR, et al. Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patients with stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salbach NM, Guilcher SJ, Jaglal SB. Physical therapists' perceptions and use of standardized assessments of walking ability post-stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sibley KM, Straus SE, Inness EL, et al. Balance assessment practices and use of standardized balance measures among Ontario physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1583–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salbach NM, Jaglal SB, Korner-Bitensky N, et al. Practitioner and organizational barriers to evidence-based practice of physical therapists for people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1284–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ammerman AS, DeVellis RF, Carey TS, et al. Physician-based diet counseling for cholesterol reduction: current practices, determinants, and strategies for improvement. Prev Med. 1993;22:96–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sibley KM, Straus SE, Inness EL, et al. Clinical balance assessment: perceptions of commonly-used standardized measures and current practices among physiotherapists in Ontario, Canada. Implement Sci. 2013;8:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greenlund KJ, Giles WH, Keenan NL, et al. Physician advice, patient actions, and health-related quality of life in secondary prevention of stroke through diet and exercise. Stroke. 2002;33:565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd ed 2007:32–78, 149,–193, 352–412. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet e-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fan W, Yan Z. Factors affecting response rates of the Web survey: a systematic review. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ontario Stroke Network overview of the Ontario Stroke System. Available at: http://ontariostrokenetwork.ca/about-the-osn/ontario-stroke-system-oss/overview-of-the-ontario-stroke-system/ Accessed August 21, 2014.

- 44. Macko RF, Smith GV, Dobrovolny CL, et al. Treadmill training improves fitness reserve in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eich HJ, Mach H, Werner C, Hesse S. Aerobic treadmill plus Bobath walking training improves walking in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:640–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graven C, Brock K, Hill K, Joubert L. Are rehabilitation and/or care co-ordination interventions delivered in the community effective in reducing depression, facilitating participation and improving quality of life after stroke? Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1501–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rimmer JH, Riley B, Creviston T, Nicola T. Exercise training in a predominantly African-American group of stroke survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1990–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duncan P, Studenski S, Richards L, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic exercise in subacute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2173–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. YMCA of Hamilton Burlington Brantford. Fit for function: community stroke wellness program. Available at: http://www.ymcahbb.ca/ Accessed August 29, 2013.

- 50. Cumming TB, Tyedin K, Churilov L, et al. The effect of physical activity on cognitive function after stroke: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Salbach NM, Mayo NE, Robichaud-Ekstrand S, et al. The effect of a task-oriented walking intervention on improving balance self-efficacy poststroke: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rimmer JH, Wang E, Smith D. Barriers associated with exercise and community access for individuals with stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Together in Movement and Exercise (TIME) program listings. Available at: http://www.uhn.ca/ Accessed July 17, 2014.

- 54. Fullerton A, Macdonald M, Brown A, et al. Survey of fitness facilities for individuals post-stroke in the greater Toronto area. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. North East Local Health Integration Network: navigating life post-stroke. Available at: http://www.nelhin.on.ca Accessed July 15, 2014.

- 56. University of Ottawa Heart Institute. How to become a Heart Wise designated provider. Available at: http://heartwise.ottawaheart.ca/professionals/about-heart-wise-exercise/how-become-heart-wise-designated-provider Accessed July 21, 2015.

- 57. Health Services for Ontario. Available at: http://www.thehealthline.ca/ Accessed July 21, 2014.

- 58. Sage Publications Inc. Social desirability. Available at: http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n537.xml Accessed September 12, 2014.