Highlights

-

•

Chyle leak is an uncommon complication of axillary node dissection.

-

•

The majority of reported cases occur on the left side, however several instances of right sided chyle leaks are reported.

-

•

The majority of chyle leaks respond to conservative management with: diet modification, pressure and drainage.

-

•

Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance for drainage, laboratory evaluation and lymphscintigraphy.

Keywords: Chyle leak, Axillary node dissection, Axillary lymphadenectomy, Mastectomy

Abstract

This report discusses the case of a chyle leak following a right axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. This presented as a sudden change in drainage character from a right axillary surgical drain from serous to milky white shortly after restarting a diet. The diagnosis of chyle leak was confirmed by laboratory testing of the fluid and managed with closed suction drainage. Chyle leak is a rare, but increasingly recognized complication following axillary clearance for breast cancer and melanoma.

1. Introduction

Chyle leak is a well recognized complication among surgeons, most frequently being encountered following radical neck dissection or intrathoracic procedures [1], [2]. However, very few surgeons are familiar with the potential for chyle leak as it exists in the setting of breast cancer/reconstruction. Typically attributed to injury of the thoracic duct, chyle leaks can be diagnosed based on the clinical presence of milky, non-purulent fluid drainage with laboratory tests serving as a useful adjunct in questionable cases. Management is usually conservative consisting of dietary modifications, adequate drainage and pressure dressings; however surgical intervention has also been advocated in certain cases [3]. We present a case of a chyle leak following a right axillary lymph node dissection and discuss the management and considerations therein.

2. Case report

A 41-year-old female was seen following diagnosis of right breast cancer. The patient had a family history of BRCA1 positive breast cancer. The patient elected to undergo bilateral skin sparing mastectomies with right-sided sentinel lymph node biopsy and immediate tissue expander reconstruction. Intraoperatively patient was found to have 2 of 4 sentinel nodes positive for disease and underwent a standard level I and II right axillary lymph node dissection. Following completion of the axillary dissection, the wound bed was felt to be dry without any noted bleeding or lymphatic leakage. The remainder of the operation, including placement of bilateral tissue expanders, was completed without complication. A drain was left on each side.

On the first post-operative day patient was noted to have serosanguinous drainage from both drains with the right draining roughly 80 cc over an 8-h period compared to 30 cc on the left. Patient was started on a regular diet beginning at noon. Roughly 4 h following patient’s first full meal the drainage in the right drain was noted to have abruptly changed to a milky color. Triglyceride level was sent on the milky drainage and was 749 mg/dl, suggesting a chyle leak. The drainage remained low output and patient was continued on a regular diet. Over the following 2 days the output of both drains decreased and the right becoming gradually less chylous in nature. The patient was discharged home with drains in place. Following discharge, the prior chylomicron screen of the right drain fluid returned positive, confirming a right sided-chyle leak. The patient was seen eleven days post-operatively and both drain outputs were noted to be serosanguinous in nature and were removed. At no point during her course did she develop any fluid collection in the right axilla.

3. Methods

A MEDLINE search was completed using the medical subject headings (MeSH) ‘axillary dissection’ and ‘chyle’ and hand searching the references. The references of each article were then examined to identify any relevant literature missed by the initial search. Each case report was examined for laterality, tumor stage, level of axillary clearance, the interval between surgery and diagnosis of chyle, the duration of the chyle leak, the volume of chyle during the first 24 h, the median volume and the administered treatment. This work is reported in line with CARE criteria [4].

4. Results

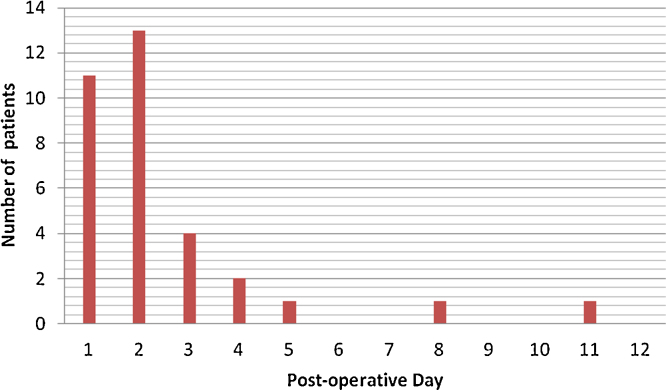

A total of 15 articles published in English were identified ranging in publication from 1993 to 2011 [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. (Table 1). A total of 37 patients, including the current case, were included (36 female, 1 male). Reason for axillary clearance included breast cancer (36 patients) and malignant melanoma (1 patient). 92% (34/37) of leaks were identified on the left side. There was no correlation found between clearance level and the volume of the chyle leak. The majority of leaks were identified in the first two post-operative days (Fig. 1). 89% (31/35) of cases resolved with conservative management; 4 patients required operative intervention. Patients requiring operative intervention had an average median daily drainage of 700 cc/day compared to 183 cc/day among those with successful conservative treatment. The average time to resolution in patients successfully treated conservatively was 12.1 days. The day of onset did not correlate with the duration of the leak.

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of chyle leak following axillary lymph node dissection.

| Incidence | Patients | Side | Breast resection | Tumor stage | Level of axillary clearance | Onset of Chyle Leak (post op day) | Duration (days) | Volume first 24 h (mL) | Median daily volume (range) (mL) | Treatment | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice et al. [10] | 1 | L | Mastectomy | NR | NR | 1 | 5 | 275 | NPO | |||

| Rijken et al. [7] | 5/591 | 5 | L | Mastectomy | T1N0 + DCIS | III | 1 | 8 | 120 (30–960) | Vacuum drain | ||

| L | Mastectomy | T1N0 + DCIS | III | 4 | 11 | 27 (30–360) | ||||||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N0 | III | 1 | 8 | 175 (30–1400) | ||||||

| L | Mastectomy | Multifocal lobular | III | 2 | 12 | (30–260) | ||||||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N2 | III | 1 | 13 | 88 (30–240) | ||||||

| L | Mastectomy | Unknown | 2 months | 400 | Editors note | |||||||

| Caluwe and Christiaens [11] | 1 | L | Breast-conserving | T1N0 + DCIS | II | 1 | 4 weeks | 210 | 125 (15–260) | Cont drainage | ||

| Purkayastha et al. [19] | 1 | L | Mastectomy | III | 1 | 14 | 1000 | TPN, re-operation on POD 14 | Leak at level 1 | |||

| Nakajima et al. [6] | 4/851 | 4 | L | Mastectomy | T1N1 | III | 3 | 1 | 60 | Closed suction drainage, serial aspiration | ||

| L | Breast conserving | T1N0 | II | 3 | 4 | 90 | 90 (70–100) | |||||

| L | Breast-conserving | T1N1 | II | 2 | 3 | 70 | 50 (40–0) | |||||

| L | Breast-conserving | T1N0 | II | 2 | 3 | 90 | 60 (20–90) | |||||

| Abdelrazeq [18] | 1 | L | Breast-conserving | T1N0 | II | 3 | 5 weeks | 450 | 100 | Aspiration, MCT diet, compression bandage | Scintigraphy scan | |

| Haraguchi et al. [12] | 1 | L | Mastectomy | T2N0 | II | 5 | 24 | 318 | 200-800 | Re-operation on POD 29 | Leak at level 1 | |

| Donkervoot et al. [13] | 1 | L | Breast-conserving | T2N2 | III | Unknown (after diet) | 7 | 170–210 | (100–210) | Cont drainage | ||

| Sakman et al. [14] | 1 | L | Mastectomy | II | 1 | 4 | 350 | Compression bandage, TPN | ||||

| Sales et al. [15] | 1 | L | SLNB, axillary dissection | Melanoma, Breslow 6 mm, T4aN1 | III | 2 | 6 | 640 | 341 (265–370) | Melanoma | Stopping suction reduced output | |

| Cong et al. [8] | 6/882 | 6 | L | Mastectomy | T2N0 | III | 2 | 5(3–7) | 170 (120–250) | Low fat diet, compression | ||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N1 | III | 2 | ||||||||

| L | Mastectomy | T1N3a | III | 2 | ||||||||

| R | Mastectomy | T2N0 | III | 2 | ||||||||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N1 | III | 2 | ||||||||

| R | Mastectomy | T1N1 | III | 2 | ||||||||

| Curcio et al. [16] | 1 | L | Breast-conserving | T2N1 | III | 1 | 13 | 500 | 500 (20–700) | Low fat then TPN | Right sided Poland Syndrome | |

| Taylor et al [9] | 1 | L | Mastectomy | Multifocal lobular | III | 11 | 2 | 120 | 20 | Cont drainage | ||

| Zhou et al. [5] | 4 | L | Mastectomy | T1N1 | II | 4 | 15.5 (7–34) | <500 | Low fat diet, compession | |||

| L | Mastectomy | T1N0 | II | 8 | <500 | |||||||

| L | Breast-conserving | T1N1 | II | 3 | <500 | |||||||

| L | Mastectomy | T1N0 | II | 1 | 6 | 700 | Re-op on POD7 | Leak from skin flap | ||||

| Singh et al. [17] | 6/1863 | 6 | L | Mastectomy | T3N1 | III | 1 | 17 | 1000 | Fat free diet, suction drain, re-operation on POD 14, mass ligature and pec minor flap | Leak at level II | |

| L | Mastectomy | T1N0 | III | 2 | 12 | 350 | Fat free diet, suction drain | |||||

| L | Mastectomy | T1N0 | III | 2 | 14 | 400 | Fat free diet, suction drain | |||||

| L | Mastectomy | T4N1 | III | 2 | 15 | 200 | Fat free diet, suction drain | |||||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N2 | III | Intraoperatve | 12 | 125 | Ligaclips intraop, suction drain | Diffuse leak at level I & II | ||||

| L | Mastectomy | T2N0 | III | Intraoperatve | 0 | 0 | Ligation of lymphatic | Leak at level II | ||||

| Daggett et al. (2014) | 1 | R | Mastectomy | T2N1 | II | 1 | 2 | 90 | 60 | Cont drainage | ||

*MCT—Medium chain triglyceride; TPN—total parenteral nutrition.

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of number of patients and the post-operative day on which chyle leak detect was detected.

5. Discussion

Chyle leak following axillary lymph node dissection is a rarely reported complication. Several small cases series have reports incidences ranging from 0.36% to 0.84% [5], [6], [7], [8]. The majority (86%) present within the first 3 days following surgery [9].

5.1. Mechanism

The mechanism for axillary chyle leak is poorly understood at this time. Chyle leaks are generally felt to result from injury of the thoracic duct. However the thoracic duct typically ascends through the chest and abdomen adjacent to the spine, crossing to the left of midline at the level of the aortic arch and finally terminating in the venous system at the base of the left neck. The majority of the variability seen in the thoracic duct involves its termination into one of several veins including: the internal jugular, external jugular, subclavian and inominate veins [20]. However, some studies have demonstrated branching of the duct in up to 30% of cases [20] and multiple terminations into the venous system in 4% of cases [21], [22]. This has led some authors to theorize that axillary chyle leaks are due to injury to an aberrant branch of the thoracic duct, [9] with drainage to the left axilla [23]. Singh et al. suggest there could be reflux of chyle through the lymphatics if the subclavian duct were to insert on the thoracic duct [17].

The vast majority of chyle leaks were noted to occur in the left axilla as would be expected given the termination of the thoracic duct in the left venous angle and the theoretical isolation of the right upper extremity lymphatics. However, Cong et al. [8] reported two cases of right-sided chyle leaks following axillary lymph node dissection with this case representing the third occurrence in the literature. Right-sided chyle leaks have also been rarely reported following though again with great rarity [24]. This occurrence is attributed to anatomic variants of the thoracic duct including paired ducts, a single right-sided duct or bilateral branching of the upper duct. All of these variants are well documented in the literature [25].

5.2. Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a chyle leak is a clinical one based on the presence of milky while drainage. This drainage typically increases with high fat meals and resolves with fasting. Laboratory testing can be used as an adjunct with examination of the fluid for triglycerides, cholesterol, protein, lipid electrophoresis, cell counts and pH [26], [27], [28], [29]. (Table 2) Lymphoscintigraphy has also been demonstrated as an effective diagnostic adjunct [21].

Table 2.

Laboratory tests used in the diagnosis of chyle leak.

| Laboratory test | Cutoff |

|---|---|

| Triglycerides | >110 mg/dL (1.24 mmol/L) – Diagnostic 50–110 mg/dL – Check for presence of chylomicrons |

| <50 mg/dL (0.56 mm/L)—Rules out (unless fasting) | |

| Protein | 20–30 gm/L |

| Cell Count | >80% Lymphocytes |

| Lipoprotein electrophoresis | Presence of chylomicrons |

| Cholesterol | <200 mg/dL (5.18 mmol/L) |

| pH | 7.40–7.80 |

The majority of chyle leaks following axillary dissection were discovered on post-operative day 1 or 2 [9]. This corresponds to the patients return to PO diet and the absorption of trigylcerides with subsequent formation of chylomicrons within the villious lymphatics. As the patient is in a fasting state intra-operatively without significant production of chylomicrons/chyle, intra-operative detection is uncommon. Singh et. al. [17] reported intra-operative detection at the time of initial surgery in 2/6 patients, observing that both had been early morning cases. They were also able to identify a leak intra-operatively on re-exploration of a patient after intentionally feeding them a high fat meal immediately prior to being placed NPO. Several other authors have recommended a 6–8 oz mixture of milk and cream or olive oil given to the patient a few hours before surgery in order to help identify the leak at the time of operation [30], [31].

5.3. Management

The majority of reported cases were managed successfully with conservative measures including: low-fat diet, pressure dressing, and negative pressure drainage. In cases of continued high output drainage the patient can be placed NPO and parenteral nutrition begun. Traditionally medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) diets were also recommended, however, more recent studies have questioned the utility this practice [32]. Suitable enteral formulas are well described in the dietary literature [33]. The use of octreotide has been described for chylous ascites or mediastinal thoracic duct injuries [34], [35], [36]. Leakage after neck dissection has been treated with a local injection of tetracycline hydrochloride [37].

In the setting of persistent leakage re-exploration and attempted ligation of the leakis recommended. Merrigan et al. [31] proposed surgical intervention when leakage persists for more than 2 weeks, drainage volume is more than 1 L/day even after 1 week, or the patient has started to experience metabolic complications. Crumley and Smith [3] and Spiro et al. [1] suggest intervention when the leakage is more than 500–600 mL/day. Direct control with suture ligation and clip application are mainstays in treatment. Various topical agents including gel foam, oxidized cellulose, and methyl-2-cyanoacrylate (tissue glue) have also been described. Two authors [17], [19] have described coverage of leak with pectoralis muscle flaps.

6. Conclusion

Chyle leak is a rare, but increasingly recognized complication following axillary clearance for breast cancer and melanoma. The majority of these cases can be managed conservatively with spontaneous resolution; however, in cases of high output or persistent drainage, operative exploration may be indicated. This case demonstrates the especially unusual complication of a chyle leak after a right-sided axillary dissection. To our understanding this represents the third reported case of this rare complication.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest are present.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethical approval

This paper did not require review by an IRB as it is not a formally designed study.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author’s contribution

Justin Daggett—Authorship, data analysis and review of paper.

Paul Smith—Authorship.

Anthony Watt—Data analysis, review of paper.

Guarantor

Justin Daggett.

References

- 1.Spiro J.D., Spiro R.H., Strong E.W. The management of chyle fistula. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:771–774. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins C.B., Mulder D.G. Chylothorax after surgery for congenital heart disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1971;61:411–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crumley R.L., Smith J.D. Postoperative chylous fistula prevention and management. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:804–813. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D.S., The CARE group The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;67(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W., Liu Y., Zha X. Management of chylous leakage after breast surgery: report of four cases. Surg. Today. 2011;41:1639–1643. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima E., Iwata H., Iwase T. Four cases of chylous fistula after breast cancer resection. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004;83:11–14. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000010675.87358.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rijken A., Chaplin B.J., Rutgers E.J.T. Chyle in the drain after modified radical mastectomy: an easy manageable problem. Breast. 1997;6:299–300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cong M.H., Liu Q., Zhou W.H. Six cases of chylous leakage after axillary lymph node dissection. Onkologie. 2008;31:321–324. doi: 10.1159/000131218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor J., Jayasinghe S., Barthelmes L. Chyle leak following axially lymh node clearance—a benign complication. Breast Care. 2011;6:130–132. doi: 10.1159/000327507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice D.C., Emory R.E., Jr., McIlrath D.C., Meland N.B. Chylous fistula: an unusual occurrence after mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;93:399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caluwe G.L., Christiaens M.R. Chylous leak: a rare complication after axillary lymph node dissection. Acta Chir. Belg. 2003;103:217–218. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haraguchi M., Kuroki T., Tsuneoka N., Furui J., Kanematsu T. Management of chylous leakage after axillary lymph node dissection in a patient undergoing breast surgery. Breast. 2006;15:677–679. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donkervoort S.C., Roos D., Borgstein P.J. A case of chylous fistula after axillary dissection in breast conserving treatment for breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2006;7:171–172. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakman G., Parsak C.K., Demircan O. A rare complication in breast cancer surgery: chylous fistula and its treatment. Acta Chir. Belg. 2007;107:317–319. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2007.11680064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sales F., Trepo E., Brondello S., Lemaitre P., Bourgeois P. Chylorrhea after axillary lymph node dissection. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007;33:1042–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curcio A., Giuricin M., Lelli D., Falcini F., Nava M.B., Folli S. Poland’s syndrome and thoracic duct anomaly. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2009;32:155–156. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh M., Suryanarayana Deo S.V., Shukla N.K. Chylous fistula after axillary lymphnode dissection: incidence, management and possible cause. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2011;11(5):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelrazeq A.S. Lymphoscintigraphic demonstration of chylous leak after axillary lymph node dissection. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2005;30:299–301. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000159521.91260.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purkayastha J., Hazarika S., Deo S.V., Kar M., Shukla N.K. Postmastectomy chylous fistula: anatomical and clinical implications. Clin. Anat. 2004;17:413–415. doi: 10.1002/ca.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Pernis P.A. Variations of the thoracic duct. Surgery. 1949;26:806–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield J., Gottlieb M.I. Variations in terminal portions of the human thoracic duct. Arch. Surg. 1956;73:955–999. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280060055012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langford R.J., Daudia A.T., Malins T.J. A morphological study of the thoracic duct at the jugulo-subclavian junction. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1999;27:100–104. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(99)80021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourgeois P., Munck D., Sales F. Anomalies of thoracic lymph duct drainage demonstrated by lymphoscintigraphy and review of the literature about these anomalies. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008;34:553–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.deGier H., Balm A., Bruning P. Systematic approach to the treatment of chylous leakage after neck dissection. Head Neck. 1996;18(4):347–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199607/08)18:4<347::AID-HED6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lane S. In: Todd R.B., editor. Vol. 3. Longman, Brown and Green; London: 1839. (The Cyclopaedia of Anatomy and Physiology). p. 225 (1847) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado F., Hawkins F.J., Daniels C.E. Pleural fluid characteristics of chylothorax. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(2):129–133. doi: 10.4065/84.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staats B.A., Ellefson R.D., Budahn L.L. The lipoprotein profile of chylous and nonchylous pleural effusions. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1980;55:700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sassoon C.S., Light R.W. Chylothorax and pseudochylothorax. Clin. Chest Med. 1985;6:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huggins J.T. Chylothorax and cholesterol pleural effusion. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010;31:743. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson C.L.N. The management of chylothorax. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1985;39:90–95. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merrigan B.A., Winter D.C., O’sullivan G.C. Chylothorax. Br. J. Surg. 1997;84:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen G.L., Mascioli E.A., Meyer L.P. Dietary modification of chyle composition in chylothorax. Gastroenterology. 1989;97(3):761–765. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCray S., Parrish C.R. When chyle leaks: nutrition management options. Pract. Gastroenterol. 2004;(May):60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collard J.M., Laterre P.F., Boemer F. Conservative treatment of postsurgical lymphatic leaks with somatostatin-14. Chest. 2000;117:902–905. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrandiere M., Hazouard E., Guicheteau V. Chylous ascites following radical nephrectomy: efficiency of octreotide as treatment of a ruptured thoracic duct. Intens. Care Med. 2000;26:484–485. doi: 10.1007/s001340051190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markman K.M., Glover J.L., Welsh R.J. Octreotide in the treatment of thoracic duct injuries. Am. Surg. 2000;66:1165–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metson R., Alessi D., Calcaterra T.C. Tetracycline sclerotherapy for chylous fistula following neck dissection. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:651–653. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780060063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]