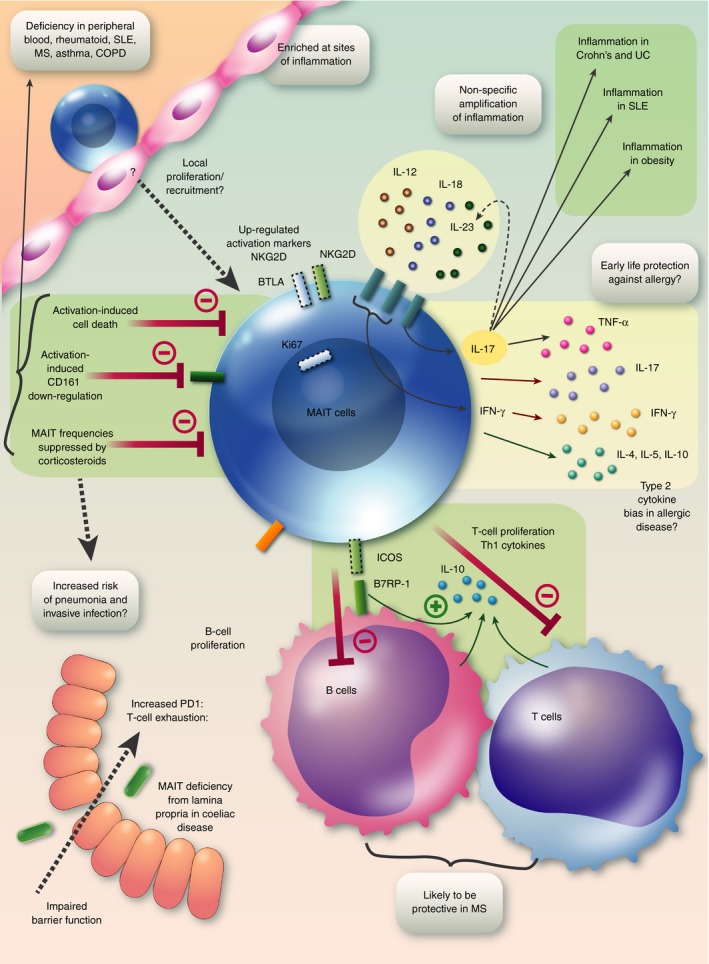

Figure 3.

Graphical summary: MAIT cells in immune‐mediated disease. A deficiency of MAIT cells in peripheral blood is probably due to several factors: suppression of MAIT cell frequencies by corticosteroids, activation‐induced cell death and down‐regulation of the popular marker CD161. The consequences of such a deficiency may include increased risk of pneumonia and invasive infections. MAIT cells are enriched at sites of disease, probably as a result of local proliferation and recruitment, and up‐regulate activation markers including NKG2D, BTLA and Ki67. Chronic stimulation may lead to T‐cell exhaustion with PD‐1 up‐regulation. Secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, especially IL‐17 will contribute to inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease, SLE and obesity. Non‐TCR‐mediated secretion of IL‐17 may be driven by IL‐23 and secretion of IFN‐γ can be driven by IL‐12 and IL‐18, allowing MAIT cells to amplify inflammatory signals in a non‐specific manner. It is possible that in allergic disease MAIT cells have a bias towards secretion of type 2 cytokines, whereas in early life microbial exposures may drive MAIT cells to produce a type 1 cytokine response protecting against the development of allergic diseases. MAIT cells may be protective in multiple sclerosis by inducing IL‐10 from T cells and particularly B cells by an MR1‐independent mechanism via ICOS–B7RP‐1 interaction. Abbreviations: B7RP‐1, B7 related protein‐1; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICOS, inducible T cell co‐stimulator; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; MAIT, mucosal‐associated invariant T; MR1, MHC‐related protein 1; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TCR, T‐cell receptor; TNF‐α, tumour necrosis factor‐α; UC, ulcerative colitis.