Summary

The modification of behavior in response to experience is crucial for animals to adapt to environmental changes. Although factors such as neuropeptides and hormones are known to function in the switch between alternative behavioral states, the mechanisms by which these factors transduce, store, retrieve and integrate environmental signals to regulate behavior are poorly understood. The rate of locomotion of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans depends on both current and past food availability. Specifically, C. elegans slows its locomotion when it encounters food, and animals in a food-deprived state slow even more than animals in a well-fed state. The slowing responses of well-fed and food-deprived animals in the presence of food represent distinct behavioral states, as they are controlled by different sets of genes, neurotransmitters and neurons. Here we describe an evolutionarily conserved C. elegans protein, VPS-50, that is required for animals to assume the well-fed behavioral state. Both VPS-50 and its murine homolog mVPS50 are expressed in neurons, are associated with synaptic and dense-core vesicles and control vesicle acidification and hence synaptic function, likely through regulation of the assembly of the V-ATPase complex. We propose that dense-core vesicle acidification controlled by the evolutionarily conserved protein VPS-50/mVPS50 affects behavioral state by modulating neuropeptide levels and presynaptic neuronal function in both C. elegans and mammals.

Introduction

Like other animals, C. elegans modulates its behavior in response to both environmental signals and past experience [1, 2]. For example, both well-fed and food-deprived worms slow their locomotion after encountering food, and well-fed worms slow less than food-deprived worms (Fig. 1A), presumably because food-deprived animals have a greater need to be in the proximity of food. The responses of well-fed and food-deprived worms upon encountering food require different sets of genes, neurotransmitters and neurons, indicating that these responses reflect two distinct behavioral states [1, 2]. The mechanisms by which animals integrate information about their current environment and their past experience to modulate behavior are poorly understood.

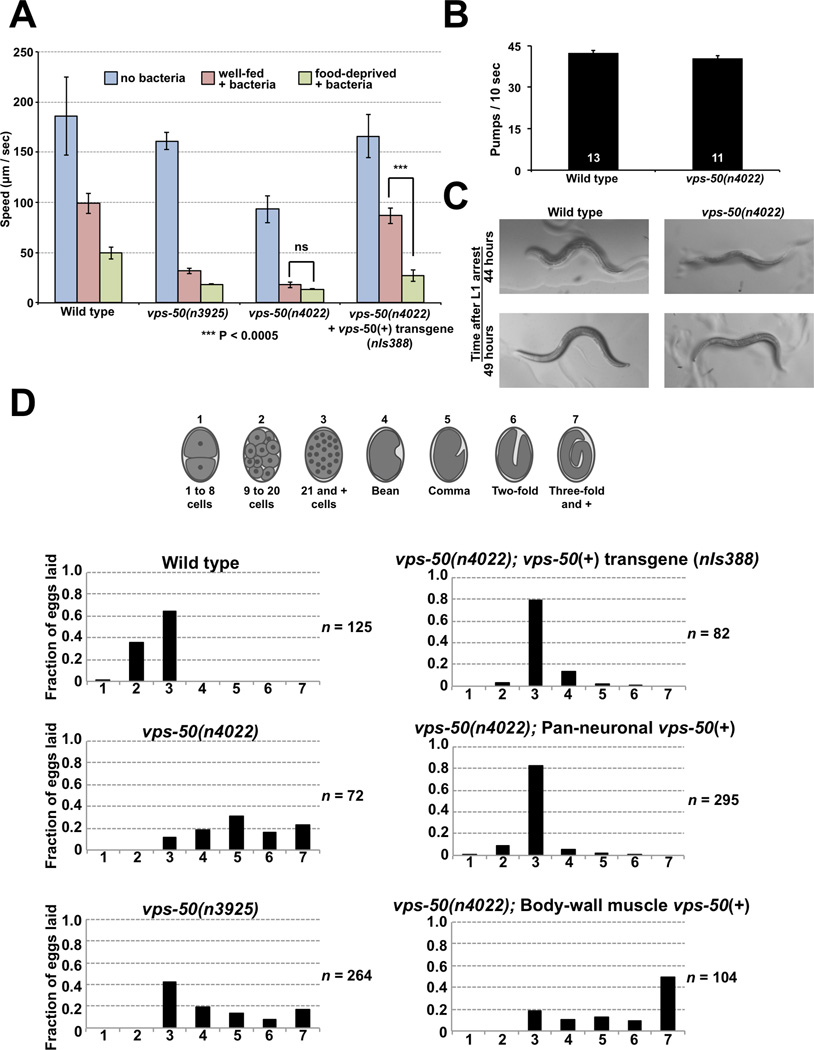

Figure 1.

VPS-50 regulates the behavioral state of C. elegans. A) The locomotory behavior of C. elegans is modulated by the presence of food and past feeding experience. Well-fed wild-type animals move more slowly on a bacterial lawn (red bars) than in the absence of bacteria (blue bars), and food-deprived animals (green bars) slow even more than well-fed animals [1]. vps-50 mutants (n3925 and n4022) moved as if they were food-deprived even when well-fed, and this behavioral defect was rescued by a transgene expressing a GFP-tagged wild-type copy of vps-50 from its endogenous promoter. n = 6 plates for the wild type; n = 3 plates for all other genotypes. Mean ± SD. B) vps-50 mutants show normal pumping rates, indicating that they do not have a feeding defect. C) vps-50 mutants develop at a rate similar to that of wild-type animals. We followed synchronized animals after recovery from L1 arrest. All wild-type and vps-50 mutant worms observed had a developed vulva after 44 hours; 12/12 wild-type animals were gravid after 49 hours, while 11/12 vps-50 mutants were gravid after 49 hours. D) Analyses of the in utero retention time of eggs, assayed by the distribution of the developmental stages of newly laid eggs. vps-50 mutants retained eggs in utero for an abnormally long period of time, as seen by a shift to later stages of their newly laid eggs. The egg-laying defect of vps-50 mutants was rescued by transgenes expressing vps-50 under its endogenous promoter or a pan-neuronal promoter but not under a body-wall muscle promoter. See also Figure S1.

Mutations that impair the maturation of dense-core vesicles and neuropeptide signaling alter the locomotion behavior of C. elegans [3]. Whereas synaptic vesicles transport and release neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, GABA and glutamate, dense-core vesicles transport and release neuromulators, such as biogenic amines and neuropeptides. In mammals, specific neuropeptides have been associated with the assumption of one of two alternative behavioral states, including hunger-satiety and sleep-wakefulness [4, 5].

From genetic screens, we isolated mutants of C. elegans that behave similarly whether they have been well-fed or food-deprived. We have characterized one gene defined by these mutations, vps-50, and show that while vps-50 mutants behave as if they have been food-deprived, they are not malnourished but rather failing to switch behavioral states: they behave as if food-deprived even when well-fed. We describe below the characterization of both C. elegans VPS-50 and its murine homolog, mVPS50 and show that both function in dense-core vesicle maturation and acidification.

Results

vps-50 regulates C. elegans behavior

To understand the mechanisms that control the behavioral states of C. elegans in response to food availability and past feeding experience, we have characterized three allelic mutations, ox476, n3925 and n4022, that cause well-fed animals to behave as if they had been food-deprived (Fig. 1A). ox476, n3925 and n4022 are alleles of an evolutionarily conserved gene, C44B9.1, which we have named vps-50 (see below) (Fig. S1A–C). vps-50 mutants have normal rates of pharyngeal pumping and do not display the slow growth and abnormal pigmentation of starved wild-type animals (Fig. 1B–C), indicating that vps-50 mutants are not malnourished but rather are in the behavioral state normally induced by acute food deprivation. vps-50 mutants are abnormal not only in locomotion but also in egg laying, as they retain eggs for an abnormally long period of time and lay eggs at substantially later developmental stages than do wild-type worms (Fig. 1D). Food-deprived wild-type worms are similarly abnormal in egg laying, further indicating that vps-50 mutants are in a food-deprived state when not food-deprived.

vps-50 acts in neurons to control C. elegans behavior

We examined the expression pattern of a transgene that expresses a VPS-50::GFP fusion under the control of the vps-50 promoter and observed that vps-50 is expressed broadly in the nervous system and possibly in all neurons (Fig. 2 and data not shown). These observations suggest that vps-50 plays a specific role in neuronal function. To determine where vps-50 functions, we used transgenes that express vps-50 in a tissue-specific manner and attempted to rescue the mutant phenotype of vps-50 mutants. Expression of vps-50 using the rab-3 pan-neuronal promoter significantly rescued both the locomotion and egg-laying defects of vps-50(n4022) mutants, while expression in body-wall muscles using the myo-3 promoter failed to rescue the locomotion and egg-laying defects of vps-50 mutants (Fig. 1D & 2B). We conclude that vps-50 functions in neurons.

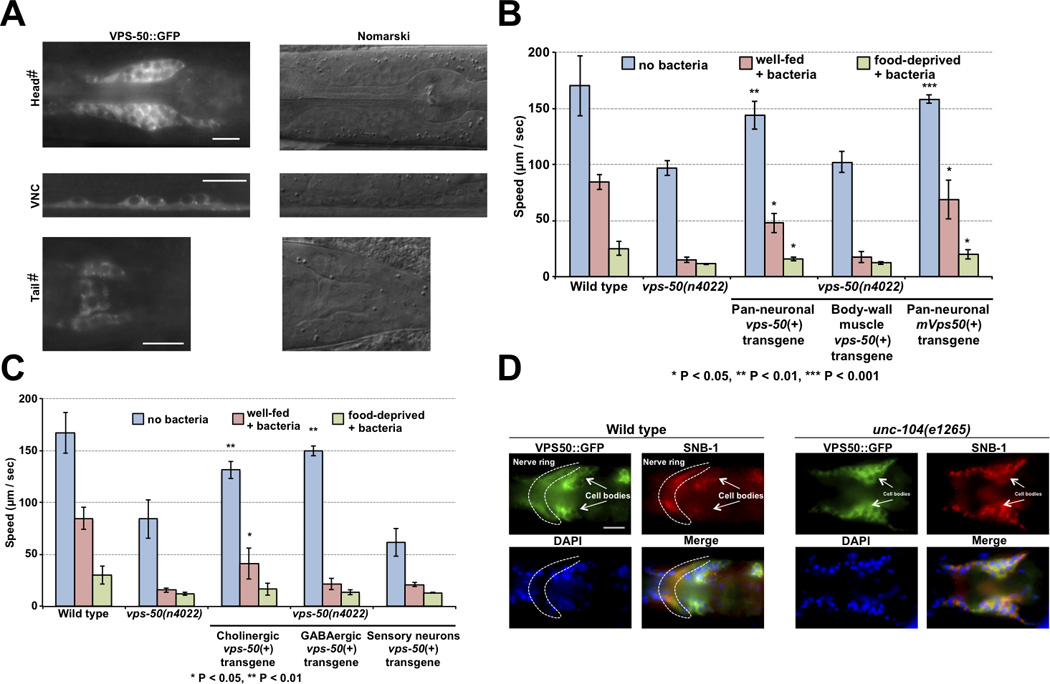

Figure 2.

VPS-50 functions in neurons. A) Fluorescence and Nomarski micrographs of regions of C. elegans transgenic animals expressing VPS-50::GFP (nIs388) using the vps-50 promoter. vps-50 was expressed in most if not all neurons. Occasional expression was observed in some pharyngeal muscles. VNC: ventral nerve cord. #To enhance visualization, we used unc-104(e1265) mutant animals to increase the fluorescence level in cell bodies. Scale bars: 10 µm. B) vps-50 functions in neurons to regulate locomotion. vps-50 was expressed pan-neuronally (Prab-3) and in body-wall muscles (Pmyo-3) to identify its site of action. Pan-neuronal expression of vps-50, or of its murine homolog mVps50, rescued the locomotion defect of vps-50(n4022) animals. n = 3 plates for all genotypes. C) vps-50 functions in cholinergic neurons to regulate locomotion on food. vps-50 was expressed in cholinergic neurons (Punc-17), in GABAergic neurons (Punc-47) and in a subset of sensory neurons (Ptax-2) to identify its site of action. n = 5 plates for the wild type and vps-50(n4022); n = 3 plates for all other genotypes. D) The localization of VPS-50::GFP to synapse-rich areas of the nerve ring depends on UNC-104/KIF1A, a molecular motor that transports synaptic vesicles and their associated proteins to synapses. Immunohistochemistry against GFP and synaptobrevin (SNB-1) and DAPI staining are shown. The dotted line indicates the synapse-rich nerve ring, and clusters of neuronal cell bodies are marked. For panels B and C, significance is defined by comparison to the equivalent state for vps-50(n4022) mutants.

To analyze further the cellular sites of function of VPS-50 in the nervous system, we expressed vps-50 in subsets of neurons. VPS-50 expression in cholinergic neurons in vps-50 mutants using the unc-17 promoter rescued the locomotion defect of well-fed vps-50 mutant worms in the presence of food, while vps-50 expression in GABAergic neurons using the unc-47 promoter did not improve the locomotion of well-fed vps-50 mutants in the presence of food (Fig. 2C). These observations suggest that vps-50 functions in cholinergic neurons to control locomotion. Expression of vps-50 using the tax-2 promoter, which drives expression in the main sensory neurons that control olfaction, gustation and thermotaxis, did not rescue the locomotion defect of vps-50 mutant worms, suggesting that this behavioral defect of vps-50 mutants is not a consequence of altered food sensing (Fig. 2C).

VPS-50 is highly conserved from worms to mammals (Fig. S1B), and pan-neuronal expression in vps-50 mutant worms of its murine homolog mCCDC132, which we refer to as mVPS50, rescued the locomotion defect of vps-50 mutants (Fig. 2B). Thus, C. elegans VPS-50 and murine mVPS50 not only are similar in sequence but also are functionally similar and likely act in similar molecular processes.

VPS-50 and its murine homolog associate with synaptic vesicles

Using an anti-GFP antibody to visualize a VPS-50::GFP fusion protein in C. elegans whole mounts, we observed VPS-50::GFP in neuronal cell bodies and also at synapse-rich regions such as the nerve ring (Fig. 2D). In C. elegans, both synaptic and dense-core vesicles as well as their associated proteins are transported to synapses by the kinesin-like protein UNC-104/KIF1A [6, 7]. Like the transport of the vesicular SNARE protein synaptobrevin (SNB-1), the transport of VPS-50 to the nerve ring required UNC-104/KIF1A, suggesting that VPS-50 associates with synaptic or dense-core vesicles (Fig. 2D).

The mammalian Vps50 gene (also known as CCDC132 or Syndetin) has been reported to be highly expressed in many regions of both the mouse and the human brains [8]. Using an antibody against VPS50, we determined that the mVPS50 protein is widely expressed in the mouse brain throughout development (Fig. 3A–C) and in most and possibly all excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Fig. 3D). We examined the distribution of mVPS50 in mouse cultured primary cortical and hippocampal neurons. mVPS50 did not colocalize with the cis-Golgi apparatus marker GM130 (Fig. 4A) but did substantially colocalize with the trans-Golgi markers Golgin-97 and TGN38 (Fig. 4B & S3A). These observations suggest that mVPS50 is at least partially localized to the trans-Golgi. The trans-Golgi apparatus has been proposed to be the final sorting compartment for both synaptic and dense-core vesicles [10]. Based on this information and our observation that C. elegans VPS-50 associates with synaptic or dense-core vesicles, we analyzed the colocalization of mVPS50 with dense-core vesicles in mouse cultured primary neurons. mVPS50 colocalized with dense-core vesicles that contained Chromogranin C or neuropeptide Y (Fig. 4C–D). The mVPS50 signal did not extend as far in the neuronal processes as did the neuropeptide signals, so it is possible that the colocalization observed between mVPS50 and neuropeptides is limited to the trans-Golgi apparatus and to early vesicles budding from it.

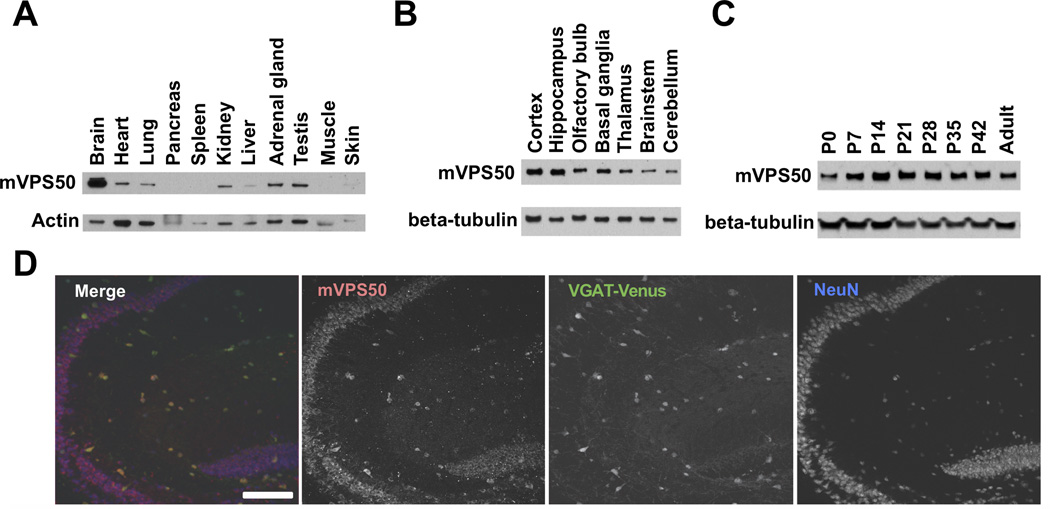

Figure 3.

mVPS50 is widely expressed in the mammalian brain neurons. Anti-VPS50 antibodies specifically recognize mVPS50 (see Fig. S2A–B for validation of the anti-mVPS50 antibody). A) mVPS50 is enriched in brain tissue. Protein extracts from dissected adult mouse tissues were analyzed for mVPS50 expression by immunoblotting. B) mVPS50 is expressed in most brain regions, with strong expression in cortex and hippocampus. C) mVPS50 is expressed in the mouse cortex throughout postnatal (P) development. Protein extracts from dissected mouse cortex were analyzed for mVPS50 expression at different developmental stages. D) mVPS50 is expressed broadly in the mouse hippocampal neurons. Transgenic mice that express VGAT-Venus in inhibitory neurons were used for immunohistochemical studies of sagittal hippocampal slices [9]. The dentate gyrus and CA3 are shown. The mVPS50 immunostaining overlaps with neuron specific marker NeuN including both Venus-positive inhibitory neurons and Venus-negative excitatory neurons. Scale bar: 100 µm. See also Figure S2.

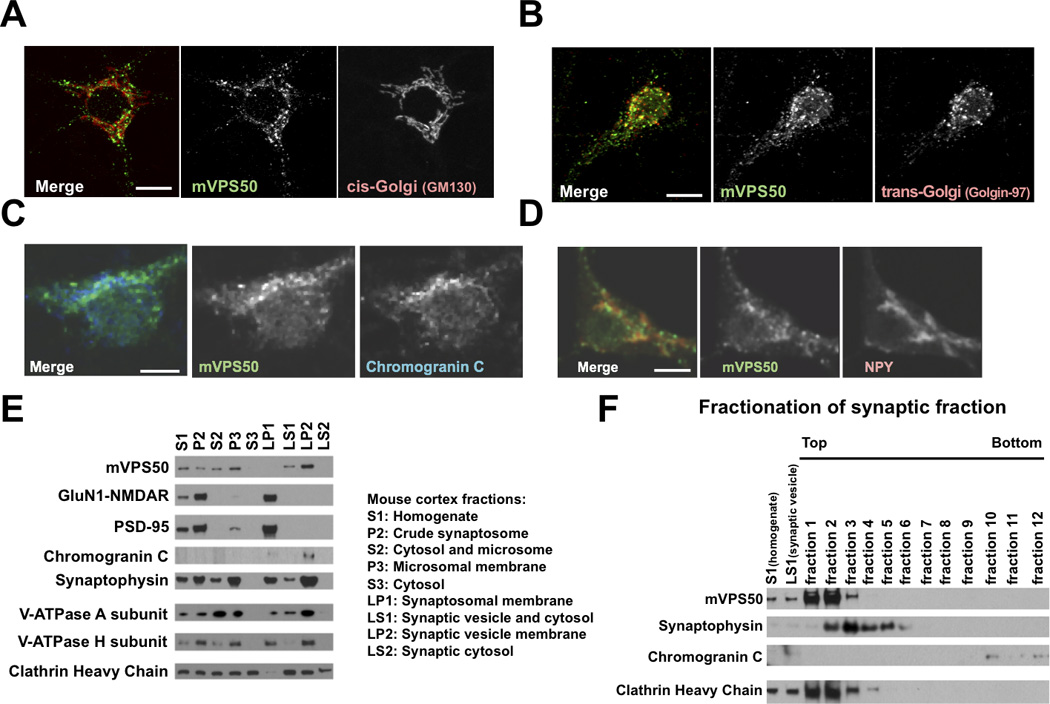

Figure 4.

mVPS50 associates with synaptic and dense-core vesicles. A) mVPS50 does not colocalize with the cis-Golgi apparatus (GM130) in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons. B) mVPS50 partially colocalizes with the trans-Golgi apparatus (Golgin-97) in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons. C) mVPS50 partially colocalizes with Chromogranin C-containing dense-core vesicles (ChrC) in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons. D) mVPS50 partially colocalizes with neuropeptide Y-containing dense-core vesicles (NPY) in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons. Endogenous mVPS50, GM130, Golgin-97, ChrC and NPY were detected by immunofluorescence. Scale bar for A–B: 10 µm. Scale bar for C-D: 5 µm. E) mVPS50 significantly cofractionates with the synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin and the neuropeptide Chromogranin C. Extracts from adult mouse cortex were fractionated, and fractions were probed by immunoblotting for mVPS50, the NMDA glutamate receptor subunit GluN1, the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95, the neuropeptide Chromogranin C, the synaptic vesicle membrane protein synaptophysin, the cytoplasmic V-ATPase A and H subunit (the mammalian homolog of C. elegans VHA-15) and the vesicle coat protein clathrin heavy chain. F) mVPS50 is a soluble protein. The synaptic vesicle and cytosol (LS1) fraction from adult mouse cortex was further fractionated using sucrose gradient centrifugation, and fractions were probed by immunoblotting. See also Figure S3.

We fractionated extracts of adult mouse cortex and showed that mVPS50 was enriched in a fraction that contained synaptic and dense-core vesicles (LP2), suggesting that like C. elegans VPS-50 the murine protein is associated with synaptic or dense-core vesicles (Fig. 4E). The LP2 fraction, which is the pellet obtained after centrifugation of fraction LS1, also contained neuropeptides, as indicated by the detection of Chromogranin C. We further fractionated the synaptic vesicle and cytosol LS1 fraction using a sucrose density gradient. The distribution of mVPS50 is like that of the clathrin heavy chain, which assembles onto vesicle membranes, and not like that of the membrane-bound synaptophysin or that of the neuropeptide Chromogranin C (Fig. 4F). We concluded that mVPS50 likely associates with synaptic vesicles as a soluble protein and is not in the lumen of vesicles or integrated into synaptic and dense-core vesicle membranes. We have not observed VPS-50 or mVPS50 at synapses in C. elegans or in mouse cultured primary neurons, respectively, indicating that these proteins likely associate with immature synaptic and dense-core vesicles budding from the trans-Golgi but do not traffic all the way to mature synapses (data not shown).

vps-50 mutant animals have a defect in dense-core vesicle maturation

The behavioral defects of vps-50 mutant worms are strikingly similar to those of mutants in unc-31 (the worm homolog of mammalian CADPS2/CAPS), rab-2 (the homolog of RAB2, which is also known as unc-67 and unc-108 in C. elegans) and rund-1 (the ortholog of RUNDC1), genes involved in the release and maturation of dense-core vesicles, but not like those of animals mutant for egl-3, which encodes a proprotein convertase that cleaves neuropeptides (Fig. 5A & Fig. S4) [3, 11–14]. unc-31 affects the release of dense-core but not of synaptic vesicles [12], suggesting that VPS-50 functionally affects dense-core vesicles. Dense-core vesicles release biogenic amines and neuropeptides. cat-2 and tph-1 mutants, which are deficient in the synthesis of dopamine and serotonin, respectively, and cat-2 tph-1 tdc-1 triple mutant animals, which are defective for the synthesis of all known biogenic amines in C. elegans [15–17], did not display the vps-50 mutant phenotype (Fig. 5B), suggesting that VPS-50 functions in neuropeptide signaling.

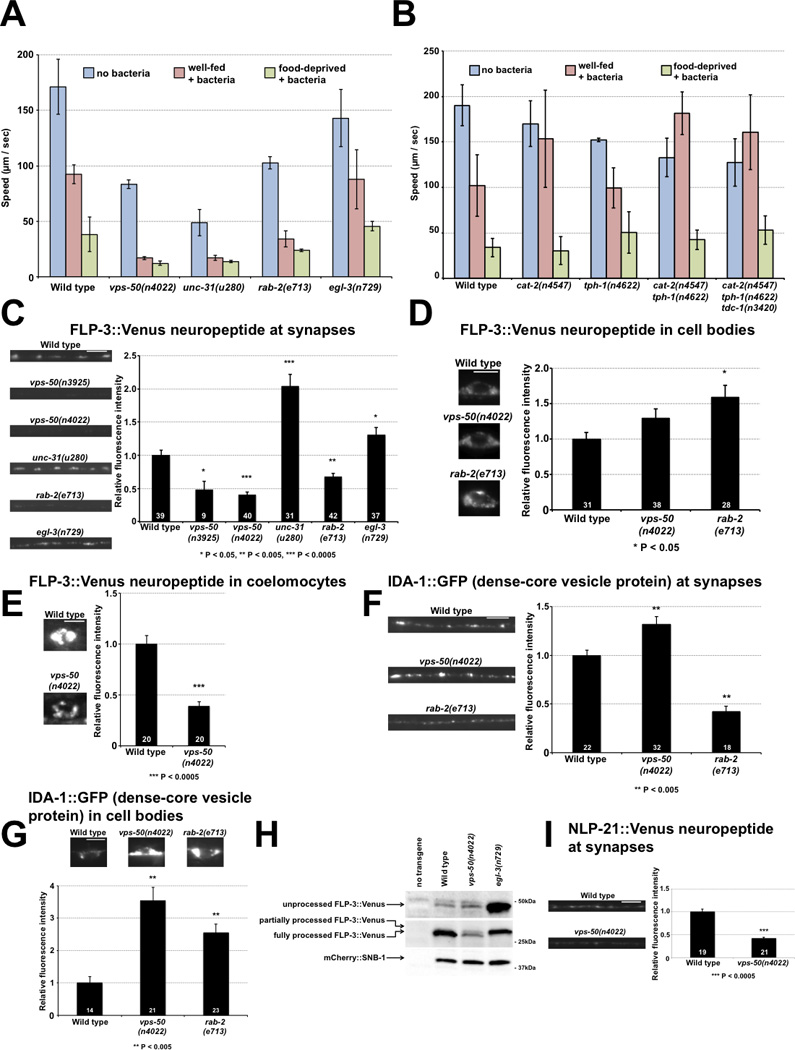

Figure 5.

vps-50 disruption reduces neuropeptide levels and impairs neuropeptide processing. A) Modulation of locomotion in response to the presence of food and past feeding experience. Like vps-50 mutants, unc-31 (CADPS2) and rab-2 (Rab2) mutants, which are defective in dense-core vesicle release and maturation, respectively, behave as if they had been food-deprived even when well-fed; egl-3 (PC2) mutants are more similar to wild-type animals. n = 4 plates for wild type; n = 3 plates for all other genotypes. B). Mutant animals defective in the synthesis of biogenic amines (cat-2: dopamine, tph-1: serotonin, tdc-1: tyramine and octopamine) behave differently when well-fed or food-deprived, unlike vps-50 mutants. n = 10 plates for wild type; n = 3 plates for all other genotypes. C) vps-50 mutants, like rab-2 mutants, show reduced FLP-3::Venus neuropeptide levels in the C. elegans dorsal nerve cord. unc-31 and egl-3 mutants show elevated neuropeptide levels at synapses. D) vps-50 mutants do not significantly accumulate FLP-3::Venus neuropeptides in neuronal cell bodies. E) vps-50 mutants have reduced levels of FLP-3::Venus neuropeptides in coelomocytes. F) vps-50 mutants do not have a dense-core vesicle maturation defect identical to that of rab-2 mutants based on the dense-core vesicle marker IDA-1::GFP in the C. elegans dorsal nerve cord. G) vps-50 mutants, like rab-2 mutants, abnormally accumulate IDA-1::GFP in ventral nerve cord cell bodies. H) vps-50 mutants have reduced levels of the neuropeptide FLP-3 as well as reduced FLP-3 processing. Immunoblots of C. elegans protein extracts showing the levels of processed and unprocessed neuropeptide FLP-3::Venus and the constant levels of the synaptobrevin reporter mCherry::SNB-1. The transgene ceIs61 expressed both FLP-3::Venus and mCherry:SNB-1 from the unc-129 promoter. Mutants for the proprotein convertase 2 homolog EGL-3 had no detectable fully processed FLP-3 neuropeptides. I) vps-50 mutants show reduced NLP-21::Venus neuropeptide levels in the C. elegans dorsal nerve cord. Scale bars: 5 µm. Bar graphs A and B, means ± SDs. Bar graphs C–G & I, n values (number of animals) are indicated on bars, representative fluorescence micrographs and quantification are shown, means ± SEMs. See also Figure S4.

To determine if vps-50 affects neuropeptides, we used a FLP-3::Venus neuropeptide fusion protein to analyze neuropeptide levels, localization, release and processing [13]. unc-31 (CADPS2/CAPS) mutants, which are impaired in the release of dense-core vesicles [12], and egl-3 (PC2) mutants, which are impaired in the processing of neuropeptides [18], accumulated elevated levels of FLP-3::Venus at synapses in the dorsal nerve cord. By contrast, rab-2 mutants, which are defective in dense-core vesicle maturation, have been reported to have decreased levels of neuropeptides at synapses [13]. vps-50 mutants, like rab-2 mutants, had decreased levels of FLP-3::Venus at synapses, revealing that vps-50 function is necessary for normal levels of synaptic neuropeptides (Fig. 5C). The FLP-3::Venus fusion did not significantly accumulate in cell bodies of vps-50 mutants, indicating that their low levels of neuropeptides at synapses were not the result of a transport defect (Fig. 5D).

Synaptic levels of neuropeptides could be low in vps-50 mutants either because of defects in producing neuropeptides or because these mutants degrade or release neuropeptides faster than wild-type animals. To assess the rate of neuropeptide release, we quantified FLP-3::Venus levels in coelomocytes, scavenger cells that take up secreted proteins from the worm’s body cavity [19]. Neuropeptide levels in coelomocytes correlate with the neuropeptide levels released from neurons [12, 20]. Coelomocytes in vps-50 mutants exhibited abnormally low levels of FLP-3::Venus (Fig. 5E), indicating that vps-50 mutants are not secreting neuropeptides faster than do wild-type animals. Taken together, these results suggest that vps-50 mutants, like rab-2 mutants, produce low levels of neuropeptides. The effect of vps-50 on neuropeptide levels at synapses is not limited to FLP-3, as an NLP-21::Venus reporter also showed low levels at synapses in vps-50 mutants as compared to wild-type animals (Fig. 5I). We postulate that mutation of vps-50 has a broad impact on neuropeptides and that the behavioral defects of vps-50 mutants is the result of the perturbation of one or of multiple neuropeptides.

We further compared vps-50 and rab-2 mutants using a transgene that expresses the dense-core vesicle marker IDA-1::GFP [13]. As previously reported, rab-2 mutants have increased levels of IDA-1::GFP in cell bodies and lower levels of IDA-1::GFP at synapses, reflecting their defect in dense-core vesicle maturation. By contrast, vps-50 mutants had elevated levels of IDA-1::GFP in both cell bodies and at synapses (Fig. 5F–G), indicating that vps-50 and rab-2 both affect dense-core vesicle maturation and do so with some differences.

Neuropeptides are produced from proproteins, which in C. elegans are cleaved into peptides by the proprotein convertase 2 enzyme EGL-3 [18]. We asked if vps-50 mutants are defective in neuropeptide processing. We examined FLP-3::Venus from protein extracts using immunoblotting and observed that vps-50 mutants had reduced levels of FLP-3 and that the ratio of processed to unprocessed FLP-3 was significantly lower than in the wild type (Fig. 5H).

In short, our results suggest that the behavioral defects of vps-50, unc-31 and rab-2 mutants are similar because all three are low in neuropeptide release. However, vps-50 mutants are distinct, because unlike unc-31 mutants they did not accumulate neuropeptides at synapses and unlike rab-2 mutants they had elevated levels of the dense-core vesicle protein IDA-1::GFP at synapses.

VPS-50 and its murine homolog affect synaptic and dense-core vesicle acidification

To identify physical partners of VPS-50, we purified recombinant VPS-50 sections fused to glutathione-S-transferase (GST-VPS-50) and probed a protein extract from wild-type C. elegans in a pull-down experiment. Using mass spectrometry, we identified VHA-15, a homolog of the H subunit of the V-ATPase complex [21], as a possible VPS-50 interactor (data not shown). We confirmed the interaction between VPS-50 and VHA-15, which might be direct or indirect, using the yeast two-hybrid system (Fig. 6A). The V-ATPase complex is a proton pump that acidifies cellular compartments, including synaptic and dense-core vesicles, the lysosome and the trans-Golgi apparatus [21, 22]. In neurons, V-ATPase activity is required for loading neurotransmitters into synaptic vesicles [23], and its disruption can impair neuropeptide processing because of a failure in acidifying vesicles to the pH optimum of processing enzymes [24]. Given the interaction between VPS-50 and VHA-15, we postulated that VPS-50 regulates or responds to the activity of the V-ATPase complex responsible for the acidification of synaptic and dense-core vesicles.

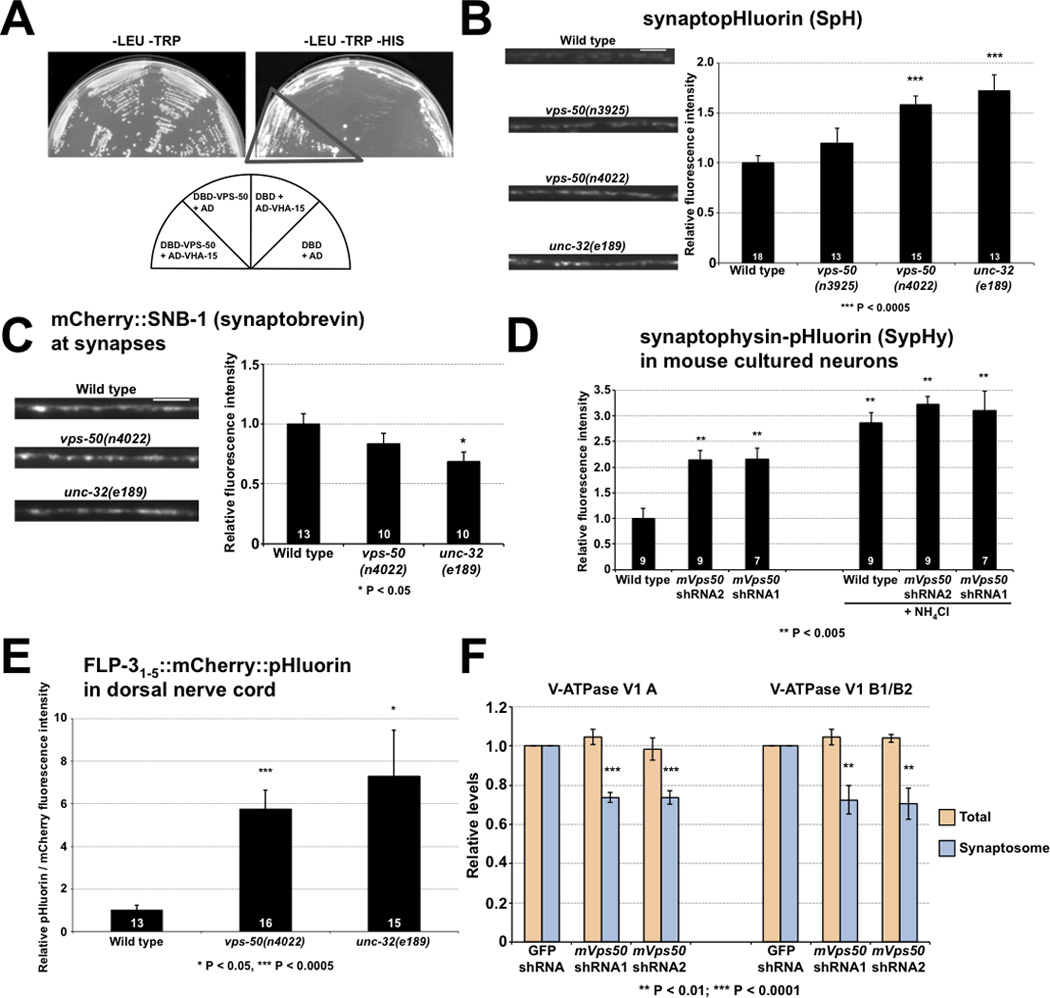

Figure 6.

Disruption of vps-50 in C. elegans or of its murine homolog mVps50 in mouse cultured neurons similarly impair synaptic vesicle acidification. A) VPS-50 can associate with the V-ATPase subunit VHA-15 in the yeast two-hybrid assay. Growth occurred on media lacking histidine (dark triangle). B) vps-50 mutants have a synaptic vesicle acidification defect. Representative micrographs and quantification of synaptopHluorin (SpH) fluorescence levels. SpH fluorescence is quenched by acidic pH; thus, increased fluorescence levels correspond to increased pH. Mutants defective in the V-ATPase complex subunit gene unc-32 were used as an acidification-defective control [25]. C) vps-50 mutants did not have elevated levels of synaptobrevin SNB-1 at synapses, indicating that the higher SpH (a SNB-1::pHluorin fusion) fluorescence levels observed in vps-50 and unc-32 mutants were not caused by elevated levels of SpH at synapses. Representative fluorescence micrographs and quantification of mCherry::SNB-1 levels at synapses. D) Knockdown of mVps50 in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons led to a synaptic vesicle acidification defect. Quantification of SypHy (synaptophysin-pHluorin fusion) fluorescence levels with or without knockdown of mVps50. Higher fluorescence levels correspond to higher pH. SypHy expression levels in wild-type and mVps50 knocked-down neurons are similar, as addition of NH4Cl to increase the intravesicular pH to 7.4 led to similar SypHy fluorescence levels in both. E) vps-50 mutants have a dense-core vesicle acidification defect. pHluorin and mCherry fluorescence intensities were quantified from FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin reporter. An increased pHluorin/mCherry fluorescence ratio indicates increased pH. Mutants defective in the V-ATPase complex subunit gene unc-32 were used as an acidification-defective control. F) Knockdown of mVps50 in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons reduces the amount of V-ATPase (V1) subunits A and B in the synaptosomal fraction. Levels of V-ATPase soluble subunits A and B were quantified in total protein extracts and in synaptosomal fractions in wild-type and mVps50 knockdown primary cultured neurons. n = 6. Scale bars: 5 µm. Bar graphs, n values (number of animals or neurons) are indicated on bars, means ± SEMs. See also Figure S5.

To investigate the effect of impaired V-ATPase function in neurons, we examined mutants defective in the V-ATPase subunit UNC-32, which is required for synaptic vesicle acidification [25, 26], using the FLP-3::Venus and IDA-1::GFP reporters described above. unc-32 mutants had low neuropeptide levels and high IDA-1::GFP levels at synapses, molecular defects similar to those of vps-50 mutants (Fig. S5A–D). (unc-32 mutants are small, sickly, and severely impaired in locomotion (Fig. S5E). For this reason unc-32 mutants cannot be assessed for locomotory responses to external cues for comparison with vps-50 mutants.) We then analyzed the acidification of synaptic and dense-core vesicles in intact worms by expressing synaptopHluorin (SpH) using the unc-17 promoter. SpH is a fusion of the synaptic-vesicle protein synaptobrevin with the pH-sensitive GFP reporter pHluorin, and the pHluorin moiety is localized to the vesicular lumen, where it can be used to assay vesicle pH [27, 28]. SpH has been used to study the effects of mutations in the V-ATPase complex on C. elegans GABAergic neurons [25]. vps-50 mutants, like unc-32 mutants, showed increased SpH fluorescence, indicating that vps-50 mutants are defective in vesicle acidification (Fig. 6B–C). unc-32 mutants share several aspects of the vps-50 mutant phenotype. However, whereas unc-32 mutants have low levels of synaptobrevin (SNB-1) at synapses, vps-50 mutants have normal levels (Fig. 6C). Since SpH is a SNB-1::pHluorin fusion, unc-32 likely has a greater effect than vps-50 on V-ATPase complex activity. The increased SpH fluorescence in vps-50 mutant animals is unlikely to be the result of SpH missorting in these mutants, as SpH colocalizes with the vesicular acetylcholine transporter UNC-17 in both wild-type and vps-50 mutant animals (Fig. S5F) and SpH localization to dorsal cord synapses in vps-50 mutants is dependent on UNC-104/KIF1A, as in the wild type (Fig. S5G). Impaired endocytosis at synapses could also lead to increased SpH fluorescence by causing an accumulation of SpH at the plasma membrane. To ask whether vps-50 mutants fail to recycle SpH, we compared them to mutants for unc-11, the AP180 homolog; unc-11 mutants fail to recycle synaptic vesicle-associated proteins like SpH and show a diffusion of SpH (and SNB-1) all along the plasma membrane [29]. The diffusion of synaptic vesicleassociated proteins in unc-11 mutants is independent of UNC-104/KIF1A function, as unc-11; unc-104 double mutants similarly show diffusion of SNB-1 along the plasma membrane in neuronal processes [29]. By contrast, we observed no such diffusion of SpH in unc-104; vps-50 double mutants (Fig. S5G). We conclude that vps-50 controls the acidification of vesicles rather than affect the levels of surface SpH.

To test if the role of VPS-50 in vesicle acidification is evolutionarily conserved, we used shRNAs to knock down mVps50 levels in mouse primary cultured cortical neurons transfected with a synaptophysin-pHluorin fusion (SypHy) [30]. We observed that neurons reduced in mVPS50 levels had higher SypHy fluorescence levels than wild-type neurons (Fig. 6D). Most SypHy signal, like the SpH signal observed in C. elegans, is from synaptic vesicles, which are more abundant than dense-core vesicles. Thus, disruption of mVps50 led to an acidification defect of synaptic vesicles in murine neurons. This observation further establishes the evolutionarily conserved functions of VPS-50 and mVPS50. Increasing the intravesicular pH to 7.4 using NH4Cl (see Experimental Procedures) increased the SypHy fluorescence of wild-type and mVps50 knockdown neurons to similar levels. Thus, the high SypHy fluorescence observed in neurons depleted for mVps50 resulted from a defect in vesicle acidification and not from a difference in SypHy expression, since neutralizing the pH of the vesicular lumen resulted in comparable SypHy fluorescence levels for wild-type and mVps50 knocked-down neurons.

Since the signals from the SpH and SypHy reporters are predominantly from synaptic vesicles, we developed a new reporter to assess the acidification of dense-core vesicles specifically. We fused both mCherry and pHluorin to the C-terminal end of a neuropeptide reporter encoding the first five neuropeptides of the flp-3 gene (FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin); neuropeptides are found in dense-core vesicles but not in synaptic vesicles. mCherry, which is largely pH-insensitive, provides an internal control. We expressed this reporter in cholinergic neurons and used the ratio of the pHluorin/mCherry fluorescence intensities as a measure of pH. (A previous study showed that such a pHluorin/mCherry ratio indicates pH [31]). The intramolecular ratiometric nature of our reporter is important, because we use this neuropeptide reporter in mutants that have altered neuropeptide levels; this reporter allows us to normalize for these different neuropeptide levels. That the FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin reporter is indeed vesicle-associated is confirmed by the observation that its transport to the dorsal nerve cord is UNC-104/KIF1A-dependent (data not shown); UNC-104/KIF1A transports dense-core and synaptic vesicles. Furthermore, the FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin reporter can be observed in coelomocytes, indicating its release (see above) and establishing that it accurately reflects neuropeptide trafficking. Since FLP-3 is a soluble peptide, the FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin reporter should be localized to the lumen of dense-core vesicles, unlike the SpH reporter (a fusion between pHluorin and the membrane protein synaptobrevin), which is localized to both synaptic vesicles and the plasma membrane. Thus, the FLP-31–5::mCherry::pHluorin reporter yields a more specific signal for intravesicular acidity than does SpH. Mutants for vps-50 and the V-ATPase subunit gene unc-32 showed impaired dense-core vesicle acidification as their pHluorin/mCherry fluorescence intensity ratios were higher than that of wild-type animals (Fig. 6E).

mVPS50 functions in the assembly of the V-ATPase complex

Taken together, our results demonstrate that C. elegans vps-50 functions in the maturation and acidification of dense-core vesicles and through the acidification process affects neuropeptide signaling. Given that VPS-50 interacts with VHA-15, the H subunit responsible for the assembly of the soluble and membrane-bound moieties of the complex, we hypothesized that through its interaction with VHA-15, VPS-50 might function in the assembly of the V-ATPase complex onto synaptic and dense-core vesicles, thus regulating vesicle acidification. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the presence of two of the soluble subunits of the V-ATPase complex, V1 subunits A and B, on synaptic vesicles in control mouse cultured primary neurons and in neurons knocked down for mVps50. The rationale for this experiment was that these soluble A and B subunits would be present on the membrane of synaptic vesicles only when the V-ATPase complex is fully assembled. We purified the synaptosomal fraction and analyzed the amounts of V-ATPase V1 A and B subunits by immunoblotting. We found that knockdown of mVps50 decreased the levels of synaptosomal V-ATPase subunits A and B as compared to control fractions (Fig. 6F). The total levels of these subunits were not affected in a whole-cell lysate, indicating that the decreased synaptosomal levels observed in the mVps50 knockdown were not caused by generally lower V-ATPase V1 A and B subunit levels (Fig. 6F). Taken together, our results suggest that C. elegans VPS-50 and its mammalian homologs are required for the proper assembly of the V-ATPase subunits into a functional holoenzyme, a process necessary for vesicle acidification. Alternatively, it is possible that VPS-50 acts in the sorting of the V-ATPase subunits to their site of assembly, which could lead to the formation of abnormal vesicles that are impaired in acidification.

Discussion

We propose that VPS-50 regulates the behavioral state of C. elegans by controlling dense-core vesicle maturation and acidification and thereby modulating neuropeptide signaling. VPS-50 and its mammalian homologs likely share an evolutionarily conserved function in V-ATPase complex assembly or sorting, leading to the generation of immature or otherwise abnormal dense-core vesicles impaired in vesicular acidification. The V-ATPase complex functions broadly to acidify cellular compartments, and the differential expression of subunit isoforms can confer cellular specificity to the localization and function of the complex [21]. It is possible that VPS-50 and its homologs regulate the V-ATPase complex specifically in neurons. VPS-50 might function in vesicle acidification as early as the trans-Golgi, from which dense-core vesicles are generated. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that fly and human VPS50 can associate with components of the Golgi-Associated Retrograde Protein (GARP) complex, which functions in retrograde transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi, suggesting that vps-50 might act in protein sorting [32–35]. GARP consists of four proteins: VPS51, VPS52, VPS53 and VPS54. VPS50 replaces VPS54 in an alternative complex, the Endosome-Associated Recycling Protein (EARP) complex, which shares the VPS51, VPS52, and VPS53 subunits with GARP. Based in those interactions, the murine and human proteins have been names VPS50. (We note that VPS50 is referred to as Syndetin [34] or VPS54L [35] in two of these studies.) These reports further suggest that VPS50 localizes in part to recycling endosomes and that knockdown of VPS50 leads to impaired recycling of proteins to the plasma membrane. These observations are consistent with our findings that vps-50 mutants show altered neuropeptide and dense-core vesicle protein levels at synapses and that mVps50-depleted neurons show impaired assembly or sorting of V-ATPase complex subunits. We suggest that the EARP complex could function in the maturation of dense-core vesicles.

unc-31 functions in dense-core vesicle release [12]. Mutations in vps-50 and unc-31 both lead to low levels of neuropeptide secretion as well as to similar behavioral phenotypes. Disruption of CADPS2, the mammalian homolog of unc-31, in both mouse and humans has been linked to autism spectrum disorders [36, 37]. In addition, a deletion spanning only hVPS50 (the human homolog of vps-50) and a second gene, CALCR (calcitonin receptor), has been reported in an autistic patient [38]. We suggest that VPS-50 plays a fundamental role in synaptic function and in the modulation of behavior and that an understanding of vps-50 and its mammalian homologs might shed light on mechanisms relevant to human behavior and possibly to neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Behavioral analysis

For locomotion analyses, young adult worms were washed off a plate with S Basal medium and allowed to sediment in a 1.5 mL tube. Liquid was removed by aspiration, and worms in about 100 µL of S Basal were transferred to the center of an assay plate seeded with an E. coli OP50 lawn covering the entire surface. For tracking in the absence of bacteria, worms were washed an extra time in S Basal before transfer to an unseeded plate. After 30 minutes in the absence of bacteria, worms were washed off with S Basal and transferred to a new seeded plate. We used a worm tracker [39] to record 10 min videos. The average speed of the population between minutes 3 and 4 of the recording is reported. The developmental stages of laid eggs were scored as described [40]. For pharyngeal pumping rates, animals were recorded at 25 fps using a Nikon SMZ18 microscope with a DS-Ri2 camera and the videos were scored for pumping events during a 10 second window.

Microscopy and immunohistochemistry

For analysis of coelomocyte fluorescence, worms were immobilized in 30 mM NaN3 on NGM pads, and z-stacks of images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Maximal intensity projections of the coelomocytes were analyzed using ImageJ. Worms expressing other fluorescent reporters were immobilized with polystyrene beads on pads made of 10% agarose in M9 and imaged using a Zeiss Axioskop II microscope and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera, with the exception of worms expressing the FLP-3::mCherry::pHluorin fusion, which were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope and a Princeton Instrument Pixis 1024 camera. Images were analyzed using ImageJ. Fluorescence intensities were quantified using a selected region of interest (ROI) from which we subtracted a background of equal size from a nearby region. The dorsal nerve cord was imaged near where the posterior gonad arm turns. For quantification of the FLP-3::mCherry::pHluorin fusion fluorescence intensities, the “Subtract background” option of ImageJ was used prior to selecting ROIs as above. For immunohistochemistry, worms were washed off plates in PBS 1× and transferred to a 1.5 mL tube. Animals were washed three times and frozen in liquid nitrogen in about 150 µL of PBS 1×. Aliquots were thawed and pressed between two glass slides and placed on dry ice for 10 min. Glass slides were pulled apart and covered in ice-cold methanol in 50 mL tubes. Worms were washed off glass slides using a Pasteur pipette, and the glass slides were removed from the tube. Tubes were centrifuged 5 min at 3700 rpm. Worms were retrieved using a Pasteur pipette and transferred to a clean 1.5 mL tube. Methanol was removed. Worms were incubated in acetone for 5 min on ice. Worms were rehydrated three times in PBS 1× and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:100) (Invitrogen) and mouse monoclonal anti-SNB-1 (1:100) antibody or mouse anti-UNC-17 (1:100) antibody (gift from J. Rand). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies coupled with Alexa 594 and Alexa 488 (1:2500), respectively (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axioskop II.

Primary hippocampal and cortical neuron cultures

All manipulations were performed in accord with the guidelines of the MIT Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary neuron cultures were prepared from embryonic day 15 (E15) mice. Hippocampus or cortex was dissected and treated with papain (Worthington) and DNaseI (Sigma) for 10 min at 37 °C and triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Cells were plated at the density of 5×104 cells / cm2 on coverslips or plastic plates that were pre-coated with alpha-laminin and poly-D-lysine and cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27.

Immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry of mouse neurons

For immunocytochemistry, mouse cultured neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, permeabilized and blocked with 5% goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour. After incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, coverslips were mounted with Fluoromount-G (Electron Microscopy Sciences). z-stack images were taken using a Nikon PCM 2000 or C2 confocal microscope with a 60× oil objective (N.A. 1.4) at 0.5 µm z-intervals. For immunohistochemistry, VGAT-Venus mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose and sectioned at 60 µm on a freezing microtome. Sagittal sections were permeabilized and blocked in 5% goat serum and 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature, and mounted with Fluoromount-G. z-stack images were taken using a Nikon PCM 2000 confocal microscope with a 10× objective (N.A. 0.5) at 10 µm z-intervals. The figures presented are projections from these confocal z-stacks. Image analysis was performed by ImageJ software. Antibodies used were: mVPS50/CCDC132 (rabbit, Sigma), Chromogranin C (mouse, Abcam), neuropeptide Y (sheep, Millipore), GFP (rat, Nacalai), NeuN (mouse, Millipore), GM130 (mouse, BD Biosciences), Golgin-97 (mouse, Santa Cruz), TGN-43 (sheep, Serotec). Secondary antibodies were: goat anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, anti-rat or anti-sheep conjugated with Alexa 488, Alexa 543 or Alexa 633 (Invitrogen).

Transfection and confocal imaging of SypHy

Cultured cortical neurons were co-transfected with SypHy and shRNA or control plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at DIV (days in vitro) 5–7 and imaged using a Nikon PCM 2000 or C2 confocal microscope with a 60× water objective (N.A. 1.0) at DIV 10–14. Imaging was performed using a modified Tyrode's solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). 50 µM AP-5 and 10 µM CNQX were added to prevent excitotoxicity. A modified Tylode solution substituting 50 mM NaCl with 50 mM NH4Cl was used to confirm the expression level of SypHy, as described previously [41].

Statistical tests

For colocalization experiments, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were obtained using the Coloc2 plugin in ImageJ. An ROI was drawn to include the cell bodies and dendrites. Bar graph comparisons were performed using Student’s t test, and multiple comparisons were corrected using the Holm-Bonferroni method. Additional experimental procedures are available in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Droste for determining DNA sequences; N. An for strain management; G. Miesenböck, L. Lagnado, Y. Yanagawa, A. Miyawaki, P. Chartrand, K. Miller, J. Rand, J.T. August, M. Nonet and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for reagents; and D. Denning, D. Ma, N. Bhatla and S. Luo for discussions. N.P. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). A.F. was supported by a NIH NRSA postdoctoral fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grant GM024663 to H.R.H and by a grant from the Simons Foundation to the Simons Center for the Social Brain at MIT to H.R.H. and M.C.-P. H.R.H. is the David H. Koch Professor of Biology at MIT and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

N.P., Y.M., A.F., D.T.O., C.L.P., M.A., M.C.-P. and H.R.H. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. N.P., Y.M., C.L.P., M.A., M.C.-P. and H.R.H. wrote the manuscript. N.P., Y.M., A.F., D.T.O., C.L.P. and M.A. performed the experiments. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to H.R.H. (horvitz@mit.edu).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Sawin ER, Ranganathan R, Horvitz HR. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron. 2000;26:619–631. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranganathan R, Sawin ER, Trent C, Horvitz HR. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin reuptake transporter MOD-5 reveal serotonin-dependent and -independent activities of fluoxetine. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5871–5884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ailion M, Hannemann M, Dalton S, Pappas A, Watanabe S, Hegermann J, Liu Q, Han H-F, Gu M, Goulding MQ, et al. Two Rab2 Interactors Regulate Dense-Core Vesicle Maturation. Neuron. 2014;82:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaab DF. Neuropeptides in hypothalamic neuronal disorders. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2004;240:305–375. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)40003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai T. The neural circuit of orexin (hypocretin): maintaining sleep and wakefulness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrn2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall DH, Hedgecock EM. Kinesin-related gene unc-104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell. 1991;65:837–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90391-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nonet ML. Visualization of synaptic specializations in live C. elegans with synaptic vesicle protein-GFP fusions. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1999;89:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto Y, Imai Y, Sugita Y, Tanaka T, Tsujimoto G, Saito H, Oshida T. CCDC132 is highly expressed in atopic dermatitis T cells. Mol Med Report. 2010;3:83–87. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Kakizaki T, Sakagami H, Saito K, Ebihara S, Kato M, Hirabayashi M, Saito Y, Furuya N, Yanagawa Y. Fluorescent labeling of both GABAergic and glycinergic neurons in vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)–Venus transgenic mouse. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1031–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JJ, Gondré-Lewis MC, Eiden LE, Loh YP. A distinct trans-Golgi network subcompartment for sorting of synaptic and granule proteins in neurons and neuroendocrine cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:735–744. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avery L, Bargmann CI, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-31 gene affects multiple nervous system-controlled functions. Genetics. 1993;134:455–464. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speese S, Petrie M, Schuske K, Ailion M, Ann K, Iwasaki K, Jorgensen EM, Martin TFJ. UNC-31 (CAPS) is required for dense-core vesicle but not synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6150–6162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1466-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards SL, Charlie NK, Richmond JE, Hegermann J, Eimer S, Miller KG. Impaired dense core vesicle maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans mutants lacking rab2. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:881–895. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumakovic M, Hegermann J, Luo L, Husson SJ, Schwarze K, Olendrowitz C, Schoofs L, Richmond J, Eimer S. UNC-108/RAB-2 and its effector RIC-19 are involved in dense core vesicle maturation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:897–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulston J, Dew M, Brenner S. Dopaminergic neurons in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Comp. Neurol. 1975;163:215–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sze JY, Victor M, Loer C, Shi Y, Ruvkun G. Food and metabolic signalling defects in a Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin-synthesis mutant. Nature. 2000;403:560–564. doi: 10.1038/35000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkema MJ, Hunter-Ensor M, Ringstad N, Horvitz HR. Tyramine Functions Independently of Octopamine in the Caenorhabditis elegans Nervous System. Neuron. 2005;46:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kass J, Jacob TC, Kim P, Kaplan JM. The EGL-3 proprotein convertase regulates mechanosensory responses of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:9265–9272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09265.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fares H, Grant B. Deciphering endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Traffic. 2002;3:11–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieburth D, Madison JM, Kaplan JM. PKC-1 regulates secretion of neuropeptides. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:49–57. doi: 10.1038/nn1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toei M, Saum R, Forgac M. Regulation and isoform function of the V-ATPases. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4715–4723. doi: 10.1021/bi100397s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriyama Y, Maeda M, Futai M. The Role of V-ATPase in neuronal and endocrine systems. J Exp Biol. 1992;172:171–178. doi: 10.1242/jeb.172.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morel N. Neurotransmitter release: the dark side of the vacuolar-H+ATPase. Biology of the Cell. 2003;95:453–457. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen EJR, Hafmans TGM, Martens GJM. V-ATPase-mediated granular acidification is regulated by the V-ATPase accessory subunit Ac45 in POMC-producing cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3330–3339. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernstrom GG, Weimer R, Pawar DRL, Watanabe S, Hobson RJ, Greenstein D, Jorgensen EM. V-ATPase V1 sector is required for corpse clearance and neurotransmission in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2012;191:461–475. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.139667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujol N, Bonnerot C, Ewbank JJ, Kohara Y, Thierry-Mieg D. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-32 gene encodes alternative forms of a vacuolar ATPase a subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11913–11921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miesenböck G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miesenböck G. Synapto-pHluorins: genetically encoded reporters of synaptic transmission. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1101/pdb.ip067827. pdb.ip067827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nonet ML, Holgado AM, Brewer F, Serpe CJ, Norbeck BA, Holleran J, Wei L, Hartwieg E, Jorgensen EM, Alfonso A. UNC-11, a Caenorhabditis elegans AP180 Homologue, Regulates the Size and Protein Composition of Synaptic Vesicles. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1999;10:2343–2360. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granseth B, Odermatt B, Royle SJ, Lagnado L. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2006;51:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koivusalo M, Welch C, Hayashi H, Scott CC, Kim M, Alexander T, Touret N, Hahn KM, Grinstein S. Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:547–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huttlin EL, Ting L, Bruckner RJ, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Szpyt J, Tam S, Zarraga G, Colby G, Baltier K, et al. The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome. Cell. 2015;162:425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wan C, Borgeson B, Phanse S, Tu F, Drew K, Clark G, Xiong X, Kagan O, Kwan J, Bezginov A, et al. Panorama of ancient metazoan macromolecular complexes. Nature. 2015;525:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nature14877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindler C, Chen Y, Pu J, Guo X, Bonifacino JS. EARP is a multisubunit tethering complex involved in endocytic recycling. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:639–650. doi: 10.1038/ncb3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillingham AK, Sinka R, Torres IL, Lilley KS, Munro S. Toward a Comprehensive Map of the Effectors of Rab GTPases. Developmental Cell. 2014;31:358–373. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadakata T, Washida M, Iwayama Y, Shoji S, Sato Y, Ohkura T, Katoh-Semba R, Nakajima M, Sekine Y, Tanaka M, et al. Autistic-like phenotypes in Cadps2-knockout mice and aberrant CADPS2 splicing in autistic patients. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI29031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadakata T, Furuichi T. Ca(2+)-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 and autistic-like phenotypes. Neurosci. Res. 2010;67:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gai X, Xie HM, Perin JC, Takahashi N, Murphy K, Wenocur AS, D’arcy M, O’Hara RJ, Goldmuntz E, Grice DE, et al. Rare structural variation of synapse and neurotransmission genes in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:402–411. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma DK, Vozdek R, Bhatla N, Horvitz HR. CYSL-1 interacts with the O2-sensing hydroxylase EGL-9 to promote H2S-modulated hypoxia-induced behavioral plasticity in C. elegans. Neuron. 2012;73:925–940. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ringstad N, Horvitz HR. FMRFamide neuropeptides and acetylcholine synergistically inhibit egg-laying by C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1168–1176. doi: 10.1038/nn.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashby MC, Rue SADL, Ralph GS, Uney J, Collingridge GL, Henley JM. Removal of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) from synapses is preceded by transient endocytosis of extrasynaptic AMPARs. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5172–5176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1042-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.