Abstract

Objectives

Prehospital hypothermia is defined as a core temperature <36.0°C and has been shown to be an independent risk factor for early death in patients with trauma. In a retrospective study, a possible correlation between the body temperature at the time of admission to the emergency room and subsequent in-hospital transfusion requirements and the in-hospital mortality rate was explored.

Setting

This is a retrospective single-centre study at a primary care hospital in Germany.

Participants

15 895 patients were included in this study. Patients were classified by admission temperature and transfusion rate. Excluded were ambulant patients and patients with missing data.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome values were length of stay (LOS) in days, in-hospital mortality, the transferred amount of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), and admission to an intensive care unit. Secondary influencing variables were the patient's age and the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Results

In 22.85% of the patients, hypothermia was documented. Hypothermic patients died earlier in the course of their hospital stay than non-hypothermic patients (p<0.001). The administration of 1–3 PRBC increased the LOS significantly (p<0.001) and transfused patients had an increased risk of death (p<0.001). Prehospital hypothermia could be an independent risk factor for mortality (adjusted OR 8.521; p=0.001) and increases the relative risk for transfusion by factor 2.0 (OR 2.007; p=0.002).

Conclusions

Low body temperature at hospital admission is associated with a higher risk of transfusion and death. Hence, a greater awareness of prehospital temperature management should be established.

Keywords: Patient blood management, Hypothermia, Transfusion, ANAESTHETICS, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using a retrospective design, we investigated the effects of prehospital hypothermia on patient in-hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and transfusion requirements in the university hospital setting.

The hospital database captured a total of 54 732 participants admitted to the emergency department of the University Hospital of Bonn between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2013.

In total, 15 895 participants with inpatient status recorded admission temperature, hospital admission and discharge dates, demographics, Glasgow Coma Scale, ICU admission, mode of transportation and information about the in-hospital mortality were eligible for full set data analyses.

The retrospective approach does not allow for causal relationships between prehospital hypothermia and any of the designated outcome measures.

The potential influence of patients’ diagnoses on temperature regulation, medication regimes and haemoglobin levels of transfused patients was not accounted for and may therefore confound observed effects.

Introduction

The incidence of prehospital hypothermia, defined as a core temperature below 36.0°C, is frequently observed in patients admitted to the emergency room (ER),1 mainly due to a difficult and prolonged rescue, infusion of cold resuscitation fluids,2 weather, age and a critical health condition. Hypothermia in combination with acidosis and coagulopathy is known as the lethal triad of death.3

Hypothermia alters enzymatic reactions of the coagulation cascade during the initiation phase and decreases platelet function,3 4 possibly leading to severe bleeding and consecutively required blood transfusion. It has been shown that the amount of applied fluids and transfused packed red blood cell (PRBC) is directly linked to hypothermia, is associated with a worse clinical outcome,5 6 and increases the risk of postoperative mortality.7 Acute complications after PRBC transfusion can comprise hypothermia, hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesiaemia, citrate toxicity, lactic acidosis and air embolism.8 Additionally, non-infectious serious hazards of transfusion (NISHOT) ranging from common complications, for example, allergic or febrile haemolytic reactions,9 to rare, life-threatening entities such as the transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)10 or the transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GVHD)11 can still pose a serious threat to patients. The patients’ outcome might also be negatively affected by non-antibody antigen-dependent reactions known as transfusion-related immune modulation9 that are suspected to increase the rate of infection and tumour recurrence after transfusion.12 The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of prehospital hypothermia on transfusion rate and mortality. This retrospective single-centre database analysis was executed in the framework of a Germany-wide multicentre initiative for patient blood management (PBM-Study: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01820949, post-results), which aims at reducing the amount of blood transfusion whenever feasible and beneficial for the patient.

Material and methods

This study reviewed the University Hospital Bonn (UHB) Emergency Department (ED) database from 1 January 2012 until 31 December 2013 that contained anonymised data of 54 732 patients. Included in this study were patients with recorded admission temperature, documented admission and discharge date, age, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mode of transportation and information about the in-hospital mortality.

As a standard operating procedure, each patient's clinical health status is evaluated by a nurse in the framework of an emergency triage system when admitted to the ED. The triage includes the tympanal measurement of the patient’s temperature. This method is easy and fast, shows accurate results and can be recommended for this purpose.13 The length of stay (LOS) was calculated electronically. The GCS was evaluated by the emergency physician arriving at the scene.

The amount of transfused red blood cells was evaluated by matching our database with the University Hospital Bonn Institute of Transfusion Medicine's database and is presented as the raw number of received packages (PRBC). The transfusion criteria are given in the German guideline: cross-sectional guidelines for therapy with blood components and plasma derivatives (2014).14

According to the German guideline: S3 prevention of perioperative hypothermia (2014), a patient was defined as hypothermic when presenting with a temperature below 36.0°C, normothermic when presenting with a temperature from 36.1°C to 38.0°C, and hyperthermic when the temperature was >38.1°C on arrival at the ED.

The primary outcome values were LOS in days, in-hospital mortality, the transferred amount of PRBCs and ICU admission.

Secondary influencing variables such as age and GCS were considered further grouping variables to compare the hypothermic patients with the normothermic and hyperthermic patients.

For quantitative data evaluation, the median test and Mann-Whitney U-test were used. To objectify if transfusion and mortality were independent of the patient's temperature, age and GCS contingency tables were created and analysed with a χ2 test. To compare means, Student's t test was used. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was applied to identify whether hypothermic and transfused patients had a higher risk of mortality than the other patients in the study. Binary logistic regression was used to determine risk factors for mortality. The univariate predictors were the body temperature and transfusion. The results are given in adjusted OR (AOR) and reached statistical significance with p<0.001. Other results are presented as mean (SD) for ordinal data, and as median for data which had expected peaks and descriptive data as raw percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics Amos V.22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, USA).

The present study was purely retrospective and approval by the ethics committee was not necessary as the General Medical Council explicitly excluded retrospective studies from approval in their code of medical ethics (§15/1).15

All collected clinical data evaluated in this study were fully anonymised before analysis. Therefore, according to prior agreement with the local ethics committee and the data protection officer appointed by the University Hospital, verbal or written informed consent was not obtained.

Results

During the 2-year study period, 15 895 of the 54 732 patients who arrived at the ED were included in the study. In total, 36 418 ambulant patients (admitted and discharged within 24 h) and patients lacking the required data were excluded. Also excluded were 1675 patients who required interdisciplinary consultation or were admitted as case conferences from other hospitals.

Of the included patients, 22.6% were hypothermic according to the German guideline, 71.8% normothermic and 5.4% hyperthermic.

The mean LOS for all study patients was 8.6 days (median 4.9 days, SD 12.3). After arrival at the ED, 14.0% of the patients were transferred to the ICU. In this group, 15.6% were hyperthermic, 14.3% normothermic and 12.7% hypothermic (p=0.3) (for demographic data, table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study population

| Variable | Total (n=15 895) | Hypothermic patients (n=3348) | Normothermic patients (n=10 517) | Hyperthermic patients (n=786) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD); [median] | 57.8 (21.1); [61] | 60.3 (20.5); [64] | 57.2 (21.1); [60] | 56.3 (20.3); [60] | <0.001 |

| Sex, male (%) | 57.3 | 59.9 | 55.5 | 62.1 | <0.001 |

| Temperature, mean (SD); [median] | 36.5 (0.8); [36.5] | 35.6 (0.5); [35.8] | 36.7 (0.4); [36.6] | 38.8 (0.6); [38.6] | <0.001 |

| Transfused (%) | 8.2 | 9.7 | 7.2 | 9.4 | <0.001 |

| PRBC total, mean amount | 0.6 | 0.7 (4.3) | 0.5 (3.0) | 0.6 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| PRBC during the first 24 h, mean (SD) | 0.8 (2.8) | 1.1 (3.2) | 0.5 (1.8) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| PRBC day 2, mean (SD) | 1.5 (3.6) | 1.8 (4.1) | 1.1 (2.6) | 0.8 (1.6) | 0.042 |

| PRBC day 3, mean (SD) | 2.2 (4.3) | 2.5 (4.8) | 1.7 (3.3) | 1.2 (1.8) | 0.05 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 | 139 | 141 | 135 | <0.001 |

| GCS, mean (SD); [median] | 12.8 (4.3); [15] | 12.3 (4.5); [15] | 13.2 (3.9); [15] | 12.7 (4.1); [15] | 0.001 |

| ICU admission (%) | 14 | 12.7 | 14.3 | 15.6 | 0.292 |

| LOS (days), mean (SD); [median] | 8.6 (12.3); [4.9] | 8.7 (12.4); [4.7] | 8.4 (11.7); [4.8] | 10.1 (13.3); [6.2] | <0.001 |

| Mortality (%) | 5.1 | 7.4 | 3.4 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

BP, blood pressure; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; PRBC, packed red blood cell.

Effects of hypothermia

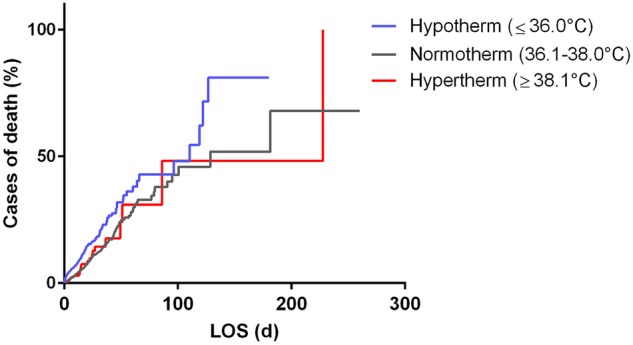

Hypothermic patients died earlier than normothermic and hyperthermic patients (p<0.001) as depicted in the Kaplan-Meier analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis: hypothermic patients had the highest mortality rate. LOS (d), length of stay in days.

Additionally, the analysis revealed that patients who died during the study period had an already decreased core temperature when admitted to the ED. Those patients had a significantly lower mean body temperature of 36.3°C (SD 1.1) than patients who were discharged alive (36.6°C, SD 0.8; p<0.001).

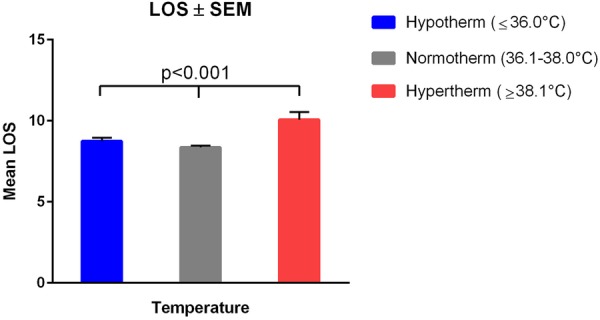

Hypothermic patients had a mean LOS of 8.7 days (median 4.7 days, SD 12.4), normothermic patients a mean LOS of 8.4 days (median 4.8 days, SD 11.6), and hyperthermic patients a mean LOS of 10.1 days (median 6.2 days, SD 13.3). The LOS of the patient groups differed significantly (p<0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

LOS in days±SEM for each temperature category. LOS, length of stay.

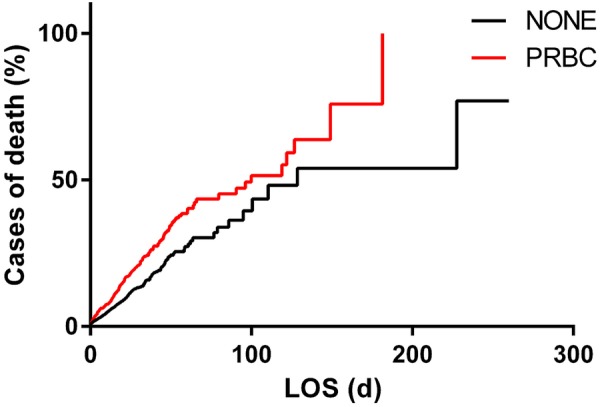

Effects of blood transfusion

Of the study patients, 1295 (8.1%) received PRBC during their stay with a median of four PRBC. Overall, 1–3 PRBC were transfused to 45.2% of the patients, 4–6 PRBC to 26.6%, 7–9 PRBC to 9.9%, and 18.3% received a massive transfusion, defined as 10 PRBC or more. The more PRBC a patient received, the longer was the LOS at the hospital (p<0.001).

The in-hospital mortality rate of 5.1% for all study-included patients increased with the number of administered PRBC. It reached 9.9% for patients with 1–3 PRBC; 14.0% for those with 4–6 PRBC, 19.0% for those with 7–9 PRBC, and 32.5% for those with ≥10 PRBC (p<0.001). Patients who died during their clinical stay received a mean amount of 13.3 (SD 16.4) PRBC.

Patients who were admitted to the ICU had a fivefold increased risk of death (AOR 5.6; 95% CI 2.0 to 15.8; p=0.001).

Referring to the Kaplan-Meier function, transfused patients died at a significantly higher rate and earlier than patients without transfusion (p<0.001), (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis: mortality of transfused patients compared with not transfused patients. LOS (d), length of stay in days; PRBC, packed red blood cell.

Referring to the used regression model, a univariate analysis for systolic blood pressure (SBP) 90/>90 mm Hg and age ≥65/<65 years showed that patients with SBP>90 mm Hg had an increased risk of death by factor 0.1 (OR 0.109; CI 95% 0.087 to 0.138; p<0.001) and that patients ≥65 years had a threefold risk of death compared with patients <65 years (OR 3.140; 2.688 to 3.669; p<0.001).

Influence of hypothermia on transfusion

Hypothermic patients received significantly more PRBC (9.7%) during their hospital stay than normothermic (7.2%) and hyperthermic patients (9.4%), (p<0.001). The binary logistic regression model revealed that both body temperature and transfusion rate are risk factors for mortality. Prehospital hypothermia (≤36.0°C) increased the risk of death up to almost 50% (AOR 1.5; 95% CI 0.7 to 3.0; p<0.001) in contrast to normothermia. Transfusion of 1–3 PRBC increased the risk of death by 20% (AOR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.3), similar to receiving 4–6 PRBC (AOR 0.3; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.4), and 7–9 PRBC (AOR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3 to 0.8; p<0.001). The administration of ≥10 PRBC increased the risk of death by factor 5 compared with patients with only 1–3 PRBC (AOR 5.7; 95% CI 1.3 to 2.2; p<0.001).

To evaluate the influence of prehospital hypothermia on the transfusion rate, further subgroups were created ((A) ≤34.5°C; (B) 34.6–34.9°C; (C) 35.0–35.4°C and (D) 35.5–36.0°C). This subgroup analysis showed that a further decreased body core temperature was associated with a rising amount of PRBCs. The analysis revealed that the amount of administered PRBCs rose from group D (9.0%) to group A (16.1%). In comparison with the hypothermic patients, only 7.2% in the normothermic group (36.1–38.0°C) and 9.4% in the hyperthermic group (>38.1) received a transfusion (p<0.001).

In a logistic regression model, an admission temperature ≤34.5°C was associated with an eightfold risk of death (AOR 8.5; 95% CI 2.5 to 28.5; p=0.001) and with an approximately twofold risk of transfusion (AOR 1.8; 95% CI 1.0 to 3.1; p=0.46). However, we calculated the relative risk for receiving PRBC in the group of patients admitted with a body temperature ≤34.5°C, and the analysis showed that these patients had a doubled relative risk (OR 2.0; CI 95% 1.3 to 3.1) of transfusion compared with normothermic patients (p=0.002).

Referring to the regression model, other univariate predictors were again SBP ≤90/>90 mm Hg and age ≥65/<65 years. This analysis showed that patients with an SBP>90 mm Hg had an increased risk of transfusion by factor 0.4 (OR 0.389; 0.301 to 0.503; p<0.001) and that patients ≥65 years showed a doubled risk of receiving transfusion compared with younger patients (OR 1.935; 1.722 to 2.175; p<0.001).

The contingency table displayed that 25% of the patients with a GCS≤8 received blood products, whereas only 7% of patients with a GCS>9 received PRBC during their stay (p<0.001). The mean GCS in transfused patients was significantly lower (GCS 10) than that in non-transfused patients (GCS 13), (p<0.001). A GCS≤8 (AOR 12.2; 95% CI 7.8 to 19.2; p=0.001) and transfusion of PRBC were connected with an increased risk of death (AOR 3.8; 95% CI 2.1 to 7.1; p=0.001). The Student’s t test revealed that hypothermic patients had a significantly lower GCS (median 12.3, SD 4.5) than normothermic patients (median 13.2, SD 3.9; p<0.001), but there was no significant difference in the GCS of hypothermic to hyperthermic patients (median 12.7, SD 4.1; p=0.47).

In our analysis, we found that 26.8% of patients accompanied by an emergency physician were hypothermic and only 19.2% of patients accompanied by paramedics were hypothermic (p<0.001).

To investigate the influence of the patient’s age on LOS and received PRBCs, three different groups were created ((1) <45 years, (2) 46–60 years and (3) >61 years). Most patients were older than 61 years (50.6%). There were 28.1% of patients aged <45 years and 21.4% between 46–60 years. Considering the median LOS, it appeared that patients belonging to group 3 stayed significantly longer at the hospital (median LOS 6.1 days) than younger patients (p<0.001). Patients belonging to group 2 stayed 4.8 days and patients who were aged 45 years and younger had a median LOS of 3.3 days.

Considering that the transfused blood products patients in group 2 received the largest amount of PRBC (mean value 10.0 PRBC, median 4 PRBC, SD 15.0), whereas patients in group 3 received a mean amount of 6.6 PRBC (median 4, SD 8.8), the patients in group 1 received 5.9 PRBC (median 3, SD 9.7).

Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the impact of hypothermia on transfusion rates and mortality at the UHB. Our findings indicate that patients presenting with hypothermia on admission to the ED have adverse outcomes compared with normothermic and hyperthermic patients. The same is applicable to hypothermic patients who received transfusions of PRBC during their hospital stay. Although it seems to be obvious that hypothermia might be a negative outcome factor during the rescue and recovery process, the incidence of hypothermia in EDs remains a commonly observed phenomenon. Heat loss that may be caused by the prolonged rescue time and severe injuries is prolonged throughout the transportation to the next ER due to a non-existing standardised prehospital warming management.

The study results show that almost one-third of the patients arrived hypothermic at the ED. We orientated ourselves on the current German guideline defining hypothermia as a core body temperature <36.0°C.16 Other studies on this subject defined hypothermia as a core body temperature <36.5°C, <35.0°C and <34.5°C.6 17 18 Setting our temperature limit at 36.0°C led to the fact that our hypothermic patients group is not as large as in, for example, the study by Bukur et al.6

In our study, hypothermic patients did not have an increased LOS. Similar results are shown by Trentzsch et al,5 whereas another paper found that patients with a body temperature <35.0°C and major trauma stayed longer at the hospital.19 Compatible results in a retrospective paper by Martin et al17 showed a significantly increased LOS and ICU admission rate for hypothermic patients with major trauma (<35.0°C) compared with normothermic patients (p<0.001). The differences in our findings compared with the studies by Ireland et al and Martin et al may be caused either by their collective of patients or by the fact that the Kaplan-Meier analysis in our study revealed that hypothermic patients had an increased mortality rate and died earlier than patients with normal or febrile temperatures. Martin et al and Ireland et al mainly used results of patients with major trauma in their studies, whereas we included every patient admitted to the ED despite the injury severity score (ISS). Our results revealed that hyperthermic patients had the longest LOS and were more often admitted to the ICU. We suggest that those patients were septic or in another febrile critical health condition that needed intensive treatment.

Hypothermic patients showed an increased consumption of PRBC and an increased risk of death. Responsible for these findings might be the partial impairment of the coagulation by hypothermia already outlined in the introduction.3 4 20 Other factors that additionally affected the coagulation of the patients included in this study cannot be retraced due to the retrospective study design.

The in-hospital death rate for patients with >10 PRBC units rose to 37.8%, whereas patients with 1–3 PRBC units had a death rate of 9.9%.The multicentred patient blood management initiative, in which this study is integrated, aims at an increase in patient safety and reduction of liberal admission of 1–3 PRBC because it was shown that already a small amount of allogeneic blood transfusion is associated with septic, pulmonary and embolic complications.21 Other possible reasons for the increased mortality rate are predisposition to nosocomial and postoperative infections, cancer recurrence and microchimerism through the infusion of PRBC.22 Our results prove that patients with 1–3 PRBC had a significantly increased LOS compared with patients who received no transfusion (p<0.001). They additionally had an enhanced risk of death (AOR 0.174; p<0.001).

Our analysis demonstrated that patients with massive transfusion died earlier than other patients. One-third of the total amount of PRBC for each massively transfused patient in the ED was administered within the first 72 h. Among this group are most likely patients with severe injuries and major trauma who are in urgent need of resuscitation fluids, for example, red blood cells as subsidised by a large retrospective study by Barbosa et al.23

There was also a significant association between the GCS and PRBC. One fourth of the patients with a GCS of ≤8 were in need of PRBC, which seems reasonable since the GCS classifies the consciousness in patients with severe injuries.

In addition, there was a difference in the occurrence of hypothermia depending on the mode of transportation. The incidence of hypothermia was significantly higher on an ambulance with an emergency physician present compared with ambulances operated by paramedics. These results indicate that patients accompanied by an emergency physician were either hypothermic due to their injuries and cold resuscitation fluids, or their body temperature was lowered protectively.

Patients aged 61 years and older had the longest LOS. Despite this result, patients in the middle-aged group (46–60 years) received the most PRBC during their stay at the hospital. The study by Barbosa et al23 displayed that age was independently associated with a higher risk of mortality in an observed 30-day period among transfused patients after trauma. According to this, our study showed that patients who died during the stay at the hospital had a mean age of 71.34 (SD 14.34), whereas patients who were discharged alive had a mean age of 57.12 (SD 21.16; p<0.001).

Limitations

Owing to the retrospective study design, it was not possible to create a causal connection between the admission temperature and the distribution of PRBC as it would be in a prospective clinical trial. This study did not include the patients' diagnoses that might have influenced the temperature regulation. Additionally, medications such as anticoagulants could not have been retraced. We were not able to retrace the exact haemoglobin level of the transfused patients and to differentiate between patients with accidental and induced hypothermia retrospectively. It has to be taken into account that ambulances are able to cool patients, and that this is a standard procedure in patients with heart attacks, cardiac arrest and patients with possible brain damage as these patients benefit from a lower core body temperature.24 25

It has to be taken into consideration that our review did not analyse the connection of the ISS of each patient with the body temperature and the transfusion requirement. This is due to the fact that it was not possible to reproduce the ISS in retrospect. A prospective controlled clinical trial on a connection between temperature, transfusion requirement and ISS could prove the importance of this subject.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this large retrospective study was able to show that prehospital hypothermia is associated with an increased transfusion requirement and a worse outcome compared with normothermic and not transfused patients.

This study should create further awareness of the importance of the patient's body temperature and a more restrictive transfusion regime for patients who are not in life-threatening need of resuscitation fluids. Patients with low prehospital body core temperatures, owing to the injury severity or a prolonged rescue, should be protected from further heat loss with trauma warming blankets. An effective warming management installed on all ambulances and in the EDs could help prevent hypothermic patients from a worse outcome as induced through the primary injury. It should be noted that this is a hypothesis suggested by the findings of this study, a prospective randomised controlled trial should be conducted to investigate, if a prehospital worming is beneficial for the patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: NK contributed to the data analysis, literature research and writing of the manuscript. IG and PM were involved in the planning of the trial. AF was responsible for the data analysis. OB and VG took part in the writing of the manuscript. GB took part in the planning of the trial and writing of the manuscript. MW participated in the planning of the trial, data analysis, literature research and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Approval for the patient blood management study was given by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Bonn chaired by Professor K Racké (number 082/13 from the 7 May 2013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mommsen P, Zeckey C, Frink M et al. . Accidental hypothermia in multiple trauma patients. Zentralbl Chir 2012;137:264–9. 10.1055/s-0030-1262604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory JS, Flancbaum L, Townsend MC et al. . Incidence and timing of hypothermia in trauma patients undergoing operations. J Trauma 1991;31:795–8; discussion 798–800 10.1097/00005373-199106000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelson AD, MacGregor H, Barnard MR et al. . Reversible inhibition of human platelet activation by hypothermia in vivo and in vitro. Thromb Haemost 1994;71:633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valeri CR, Feingold H, Cassidy G et al. . Hypothermia-induced reversible platelet dysfunction. Ann Surg 1987;205:175–81. 10.1097/00000658-198702000-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trentzsch H, Huber-Wagner S, Hildebrand F et al. . Hypothermia for prediction of death in severely injured blunt trauma patients. Shock 2012;37:131–9. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318245f6b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukur M, Hadjibashi AA, Ley EJ et al. . Impact of prehospital hypothermia on transfusion requirements and outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:1195–201. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31826fc7d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochicchio GV, Napolitano L, Joshi M et al. . Outcome analysis of blood product transfusion in trauma patients: a prospective, risk-adjusted study. World J Surg 2008;32:2185–9. 10.1007/s00268-008-9655-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuehnert MJ, Roth VR, Haley NR et al. . Transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection in the United States, 1998 through 2000. Transfusion (Paris) 2001;41:1493–9. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41121493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrickson JE, Hillyer CD. Noninfectious serious hazards of transfusion. Anesth Analg 2009;108:759–69. 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181930a6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlaar APJ, Juffermans NP. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: a clinical review. Lancet 2013;382:984–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62197-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM): an update. Blood Rev 2007;21: 327–48. 10.1016/j.blre.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheson AG, Brookes MJ, Spahn DR et al. . Effects of allogeneic red blood cell transfusions on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2012;256:235–44. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825b35d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jefferies S, Weatherall M, Young P et al. . A systematic review of the accuracy of peripheral thermometry in estimating core temperatures among febrile critically ill patients. Crit Care Resusc 2011;13:194–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vorstand der Bundesärztekammer auf, Empfehlung des Wissenschaftlichen Beirats. Querschnitts-Leitlinien (BÄK) zur Therapie mit Blutkomponenten und Plasmaderivaten—4. überarbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage 2014.

- 15.Berufsordnung für Ärztinnen und Ärzte—Ärztekammer Nordrhein 2013. http://www.aekno.de (accessed 4 Jun 2015).

- 16.Torossian A, Bein B, Bräuer A et al. . S3 Leitlinie Vermeidung von perioperativer Hypothermie 2014. AWMF, 2014. http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/001-018l_S3_Vermeidung_perioperativer_Hypothermie_2014-05.pdf (accessed 3 Nov 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin RS, Kilgo PD, Miller PR et al. . Injury-associated hypothermia: an analysis of the 2004 National Trauma Data Bank. Shock 2005;24:114–18. 10.1097/01.shk.0000169726.25189.b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentilello LM, Jurkovich GJ, Stark MS et al. . Is hypothermia in the victim of major trauma protective or harmful? A randomized, prospective study. Ann Surg 1997;226:439–47; discussion 447–9 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ireland S, Endacott R, Cameron P et al. . The incidence and significance of accidental hypothermia in major trauma—a prospective observational study. Resuscitation 2011;82:300–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martini WZ. Coagulopathy by hypothermia and acidosis: mechanisms of thrombin generation and fibrinogen availability. J Trauma 2009;67:202–8; discussion 208–9 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a602a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glance LG, Dick AW, Mukamel DB et al. . Association between intraoperative blood transfusion and mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2011;114:283–92. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182054d06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghavan M, Marik PE. Anemia, allogenic blood transfusion, and immunomodulation in the critically ill. Chest 2005;127:295–307. 10.1378/chest.127.1.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbosa RR, Rowell SE, Sambasivan CN et al. . A predictive model for mortality in massively transfused trauma patients. J Trauma 2011;71:S370–4. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318227f18f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD et al. . Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:557–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa003289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clifton GL, Miller ER, Choi SC et al. . Hypothermia on admission in patients with severe brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2002;19: 293–301. 10.1089/089771502753594864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]