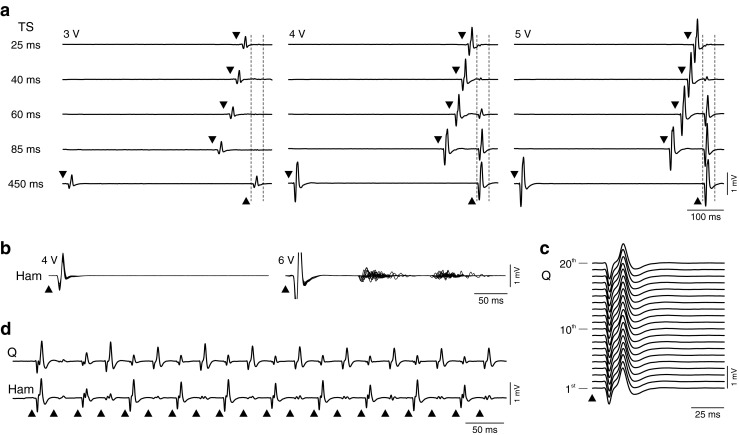

Fig. 2.

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) activates spinal reflex circuitry. (a) Responses to paired pulses at conditioning test intervals and stimulation intensities as indicated. Stimulus application is marked by black arrowheads; vertical dashed lines show time windows of second responses. The reflex nature of the responses is revealed by the depression with decreasing interstimulus intervals. The degree of recovery increases with the size of the unconditioned reflex. Triceps surae (TS) of an individual with complete spinal cord injury (SCI) [subject 1 in [30], classified as American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grade A; neurological level of injury: C7). (b) Response types to single stimulus pulses. Each graph shows 20 superimposed responses of hamstrings (Ham) from a person with motor complete, sensory incomplete SCI (subject 6 in [51], AIS grade B; neurological level: T8). Each pulse evoked a short-latency posterior root-muscle (PRM) reflex, without (left) or with long-latency, polysynaptic responses. (c) Response behavior during repetitive stimulation. Monosynaptic PRM reflexes evoked by 2-Hz SCS. First 20 responses of quadriceps (Q) of an individual with complete SCI (subject 4 in [45], AIS grade A; neurological level: C5). Note the repeatability of the response waveform. (d) With increasing frequency, neural circuits involved in the regulation of spinal reflex activity are integrated, as reflected here by the patterns of PRM reflex modulation; 16 Hz, same subject as in (c). Note the reciprocal relationship between Q and Ham muscles