Abstract

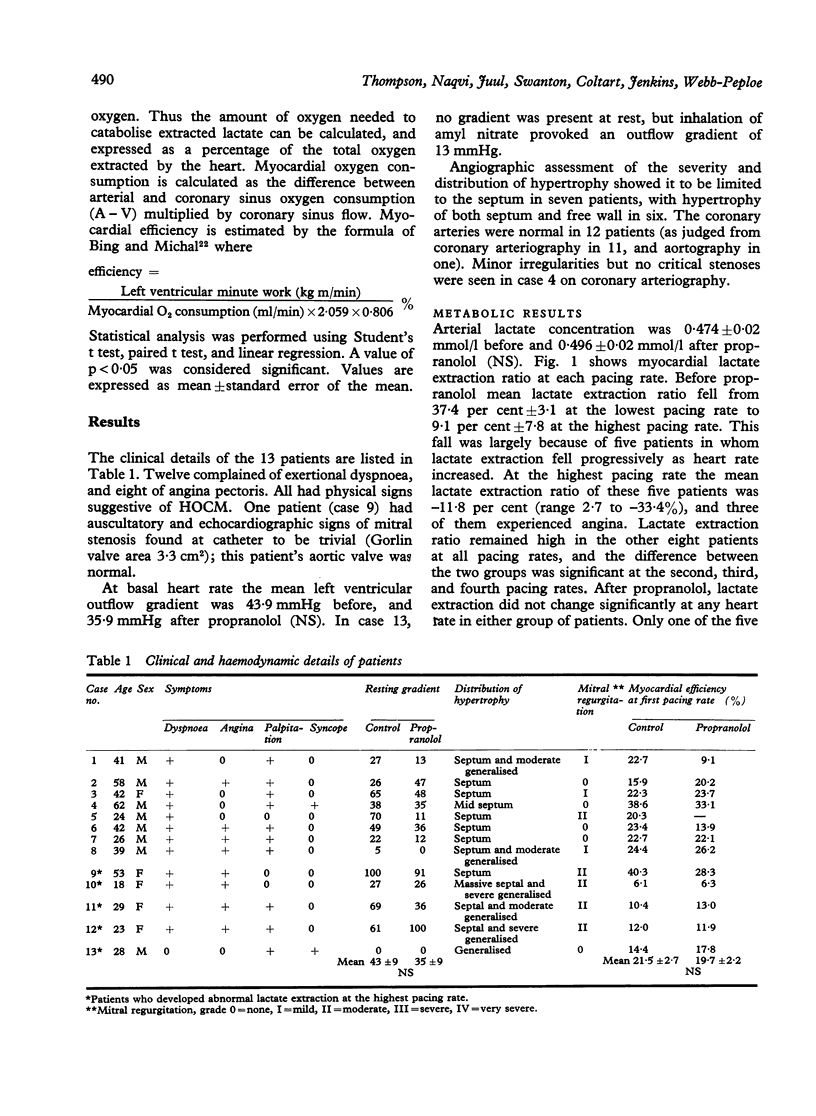

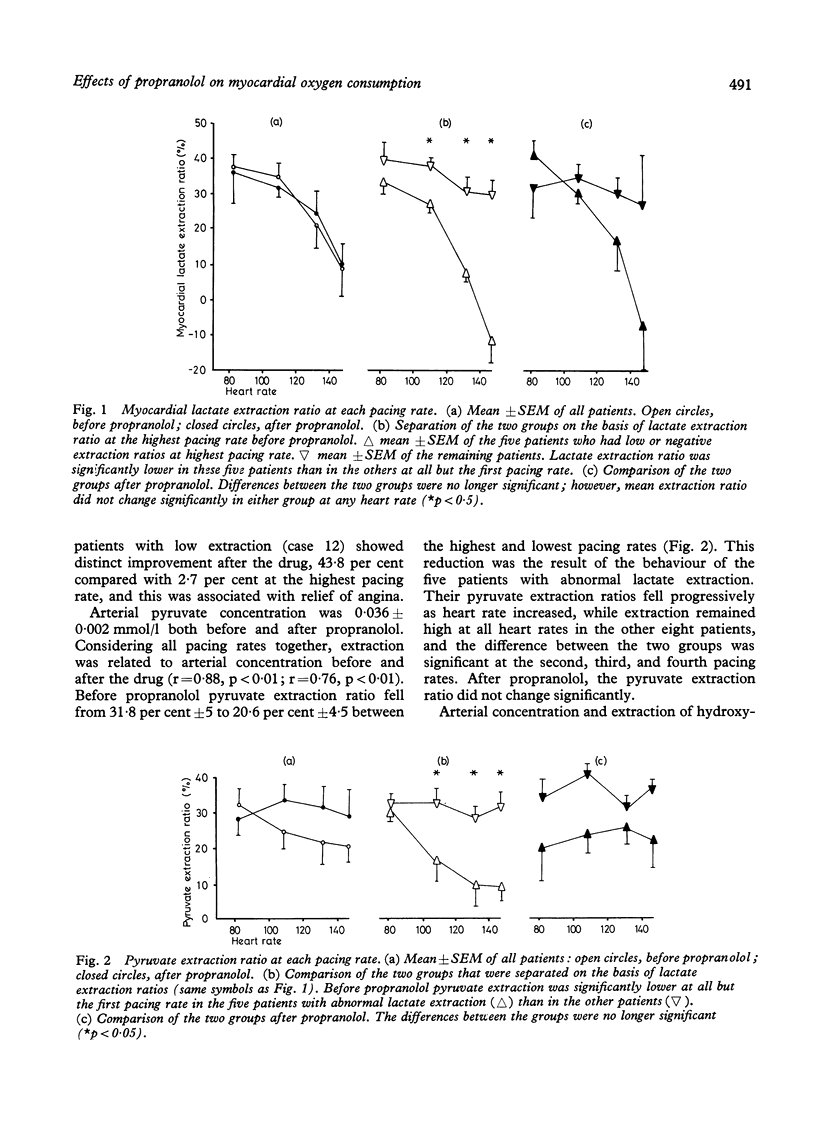

Myocardial substrate extraction, coronary sinus flow, cardiac output, and left ventricular pressure were measured at increasing pacing rates before and after propranolol (0.2 mg/kg) in 13 patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) during diagnostic cardiac catheterisation. At the lowest pacing rate myocardial oxygen consumption varied considerably between patients and very high values were found in several individuals (range 10.1 to 57.5 ml/min). These large differences between patients were not explicable by differences in cardiac work; consequently, cardiac efficiency, estimated from the oxygen cost of external work, varied between patients and was lower than normal in all but two. The pattern of substrate extraction at the lowest pacing rate was similar to results reported for the normal heart, and measured oxygen consumption could be accounted for by complete oxidation of the substrates extracted; thus there was no evidence of a gross abnormality of oxidative metabolism, suggesting that low efficiency lay in the utilisation rather than in the production of energy. Each of the four patients with the highest myocardial oxygen consumption and lowest values of efficiency sustained progressive reductions in lactate and pyruvate extraction as heart rate increased, and at the highest pacing rate had low (< 3%) or negative lactate extraction ratios. In three of these four, coronary sinus flow did not increase progressively with each increment in heart rate. One patient with low oxygen consumption and normal efficiency also failed to increase coronary flow with the final increment in heart rate, and produced lactate at the highest pacing rate. Thus the five patients in whom pacing provoked biochemical evidence of ischaemia all had excessive myocardial oxygen demand and/or limited capacity to increase coronary flow. Propranolol did not change lactate extraction significantly at any pacing rate in either the ischaemic or non-ischaemic groups. In only one patient was ischaemia at the highest pacing rate abolished after propranolol, and this was associated with a 30 per cent reduction in oxygen consumption. These results do not demonstrate a direct effect of propranolol upon myocardial metabolism in patients with HOCM, but emphasise the potential value of beta-blockade in protecting these patients from excessive increases in heart rate.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BING R. J. CARDIAC METABOLISM. Physiol Rev. 1965 Apr;45:171–213. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1965.45.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BING R. J., MICHAL G. Myocardial efficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959 Feb 6;72(12):555–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb44182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BING R. J., SIEGEL A., UNGAR I., GILBERT M. Metabolism of the human heart. II. Studies on fat, ketone and amino acid metabolism. Am J Med. 1954 Apr;16(4):504–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BING R. J., SIEGEL A., VITALE A., BALBONI F., SPARKS E., TAESCHLER M., KLAPPER M., EDWARDS S. Metabolic studies on the human heart in vivo. I. Studies on carbohydrate metabolism of the human heart. Am J Med. 1953 Sep;15(3):284–296. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(53)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAUNWALD E., LAMBREW C. T., ROCKOFF S. D., ROSS J., Jr, MORROW A. G. IDIOPATHIC HYPERTROPHIC SUBAORTIC STENOSIS. I. A DESCRIPTION OF THE DISEASE BASED UPON AN ANALYSIS OF 64 PATIENTS. Circulation. 1964 Nov;30:SUPPL 4–119. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.29.5s4.iv-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby I. A., Swanton R. H., Jenkins B. S., Webb-Peploe M. M. Long sheath technique for introduction of catheter tip manometer or endomyocardial bioptome into left or right heart. Br Heart J. 1974 Sep;36(9):908–912. doi: 10.1136/hrt.36.9.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley B. H., Weisfeldt M. L., Hutchins G. M. Isometric cardiac contraction. a possible cause of the disorganized myocardial pattern of idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1977 Jan 20;296(3):135–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197701202960303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers M., Young D. A. Free fatty acid estimation by a semi-automated fluorimetric method. Clin Chim Acta. 1973 Dec 27;49(3):341–348. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(73)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. S., Braunwald E. Amelioration of angina pectoris in idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis with beta-adrenergic blockade. Circulation. 1967 May;35(5):847–851. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.5.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge H. T., Baxley W. A. Hemodynamic aspects of heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1968 Jul;22(1):24–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(68)90243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallen E. L., Elliott W. C., Gorlin R. Mechanisms of angina in aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1967 Oct;36(4):480–488. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.36.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamm M. D., Harrison D. C., Hancock E. W. Muscular subaortic stenosis. Prevention of outflow obstruction with propranolol. Circulation. 1968 Nov;38(5):846–858. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.38.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODALE W. T., OLSON R. E., HACKEL D. B. The effects of fasting and diabetes mellitus on myocardial metabolism in man. Am J Med. 1959 Aug;27:212–220. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODWIN J. F., HOLLMAN A., CLELAND W. P., TEARE D. Obstructive cardiomyopathy simulating aortic stenosis. Br Heart J. 1960 Jun;22:403–414. doi: 10.1136/hrt.22.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz W., Tamura K., Marcus H. S., Donoso R., Yoshida S., Swan H. J. Measurement of coronary sinus blood flow by continuous thermodilution in man. Circulation. 1971 Aug;44(2):181–195. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin J. F., Oakley C. M. The cardiomyopathies. Br Heart J. 1972 Jun;34(6):545–552. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.6.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOHORST H. J., KREUTZ F. H., BUECHER T. [On the metabolite content and the metabolite concentration in the liver of the rat]. Biochem Z. 1959;332:18–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood W. B., Jr Regional venous drainage of the human heart. Br Heart J. 1968 Jan;30(1):105–109. doi: 10.1136/hrt.30.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins G. M., Bulkley B. H. Catenoid shape of the interventricular septum: possible cause of idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Circulation. 1978 Sep;58(3 Pt 1):392–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson G., Atkinson L., Oram S. Improvement of myocardial metabolism in coronary arterial disease by beta-blockade. Br Heart J. 1977 Aug;39(8):829–833. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.8.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREUTZ F. H. [Enzymatic glycerin determination]. Klin Wochenschr. 1962 Apr 1;40:362–363. doi: 10.1007/BF01732450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolettis M., Jenkins B. S., Webb-Peploe M. M. Assessment of left ventricular function by indices derived from aortic flow velocity. Br Heart J. 1976 Jan;38(1):18–31. doi: 10.1136/hrt.38.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassers B. W., Kaijser L., Wahlqvist M. L., Carlson L. A. Relationship in man between plasma free fatty acids and myocardial metabolism of carbohydrate substrates. Lancet. 1971 Aug 28;2(7722):448–450. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhart J. W., Hildner F. J., Barold S. S., Listejw, Samet P. Left heart hemodynamics during angina pectoris induced by atrial pacing. Circulation. 1969 Oct;40(4):483–492. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhart J. W. Pacing-induced changes in stroke volume in the evaluation of myocardial function. Circulation. 1971 Feb;43(2):253–261. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathey D. G., Chatterjee K., Tyberg J. V., Lekven J., Brundage B., Parmley W. W. Coronary sinus reflux. A source of error in the measurement of thermodilution coronary sinus flow. Circulation. 1978 Apr;57(4):778–786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.57.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien K. P., Higgs L. M., Glancy D. L., Epstein S. E. Hemodynamic accompaniments of angina: a comparison during angina induced by exercise and by atrial pacing. Circulation. 1969 Jun;39(6):735–743. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.39.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. O., Khaja F., Case R. B. Analysis of left ventricular function by atrial pacing. Circulation. 1971 Feb;43(2):241–252. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODBARD S., WILLIAMS C. B., RODBARD D., BERGLUNG E. MYOCARDIAL TENSION AND OXYGEN UPTAKE. Circ Res. 1964 Feb;14:139–149. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redwood D. R., Scherer J. L., Epstein S. E. Biventricular cineangiography in the evaluation of patients with asymmetric septal hypertrophy. Circulation. 1974 Jun;49(6):1116–1121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.6.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schang S. J., Pepine C. J. Effects of propranolol on coronary hemodynamic and metabolic responses to tachycardia stress in patients with and without coronary disease. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1977;3(1):47–57. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810030106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen S. Effect of atenolol (ICI 66 082) on coronary haemodynamics in man. Br Heart J. 1977 Nov;39(11):1210–1216. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.11.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloman G. Propranolol in management of muscular subaortic stenosis. Br Heart J. 1967 Sep;29(5):783–787. doi: 10.1136/hrt.29.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton R. H., Brooksby I. A., Jenkins B. S., Webb-Peploe M. M. Hemodynamic studies of beta blockade in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Eur J Cardiol. 1977 Jun;5(4):327–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. S., Naqvi N., Juul S. M., Coltart D. J., Jenkins B. S., Webb-Peploe M. M. Haemodynamic and metabolic effects of atenolol in patients with angina pectoris. Br Heart J. 1980 Jun;43(6):668–679. doi: 10.1136/hrt.43.6.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMSON D. H., MELLANBY J., KREBS H. A. Enzymic determination of D(-)-beta-hydroxybutyric acid and acetoacetic acid in blood. Biochem J. 1962 Jan;82:90–96. doi: 10.1042/bj0820090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigle E. D., Silver M. D. Myocardial fiber disarray and ventricular septal hypertrophy in asymmetrical hypertrophy of the heart. Circulation. 1978 Sep;58(3 Pt 1):398–402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson S., Heinle R. A., Herman M. V., Kemp H. G., Sullivan J. M., Gorlin R. Propranolol and angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1966 Sep;18(3):345–353. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(66)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierler K. L. Fatty acids as substrates for heart and skeletal muscle. Circ Res. 1976 Jun;38(6):459–463. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.6.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]