Abstract

The spectrum of neurological complications associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is broad. The most frequent etiologies include primary diseases (caused by HIV itself) or secondary diseases (opportunistic infections or neoplasms). Despite these conditions, HIV-infected patients are susceptible to other infections observed in patients without HIV infection. Here we report a rare case of a brain abscess caused by Staphylococcus aureus in an HIV-infected patient. After drainage of the abscess and treatment with oxacilin, the patient had a favorable outcome. This case reinforces the importance of a timely neurosurgical procedure that supported adequate management of an unusual cause of expansive brain lesions in HIV-1 infected patients.

Keywords: Brain abscess, HIV, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Staphyloccocus aureus

INTRODUCTION

The spectrum of neurological complications associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is extremely heterogeneous and includes primary diseases (caused by HIV itself) or secondary (opportunistic infections or neoplasms). Opportunistic neurological manifestations can be classified according to the predominant neurological syndrome involved in meningeal or encephalic syndrome. The encephalic syndrome can be classified in focal or with diffuse involvement and focal brain lesions may or may not show mass effect1. Cerebral toxoplasmosis represents the most frequent cause of expansive brain lesions in HIV-infected patients. In Brazil, focal forms of the central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis (particularly tuberculomas and rarely abscesses) constitute the main differential diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis. Primary CNS lymphomas are uncommon in our setting2. Several other infections may occasionally present with focal lesions in HIV-infected patients, including Nocardia species, Varicella-zoster virus, Aspergillus species, Listeria monocytogenes, Treponema pallidum, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Cryptococcus neoformans. Some of these microorganisms are more commonly causes of meningitis, but they may cause focal processes3.

In addition to neurological complications associated with HIV-1 infection, these patients can present etiologies that are not commonly associated with immunossupression. In this report, we present the case of a HIV-1 infected patient with a brain abscess caused by Staphylococcus aureus and discuss several challenging issues about the management of expansive brain lesions in this kind of host.

CASE REPORT

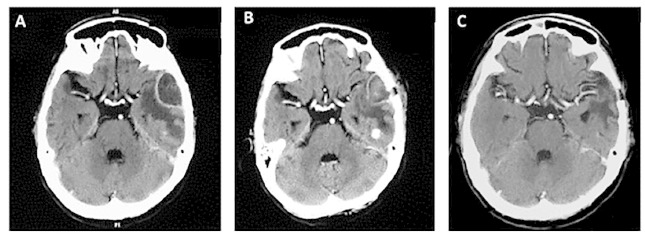

A 76-year-old man was admitted to the emergency room after being found disoriented by his family. He experienced episodes of fever (38-39.5 °C) in previous days. There were no other complaints including headache or seizures. His prior history included an HIV-1 infection diagnosed 10 years before, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and hyperthyroidism. His medications included zidovudine, lamivudine, efavirenz, tiamazol, and captopril. The last laboratorial results showed a CD4 cell count of 668 cells/mm3 and HIV viral load < 50 copies/mL. At admission, the physical examination showed a patient in good general conditions, moderately dehydrated and pale, afebrile, and hemodynamically stable. The neurological exam showed disorientation in time and space with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 14. The rest of the examination was normal. Laboratorial tests showed leukocytosis with left shift and no other alterations. A brain computed tomography scan showed a single low attenuation lesion with a uniform ring enhancement in the left temporal region (Fig. 1A). At this moment, empiric treatment for toxoplasmosis with parenteral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (5/ 25 mg/ kg twice a day) was initiated. Seven days later, the patient's level of consciousness worsened, presenting disorientation and confusion. At this moment, after a review of the prior images, the hypothesis of bacterial or mycobacterial brain abscess was considered and ceftriaxone (2 g twice a day) and metronidazole (500 mg three times a day) were started. A lumbar puncture showed 1 cell/dL, 56 mg/dL of glucose, and 40 mg/dL of proteins. The cerebrospinal fluid direct exam and bacteria, fungus and mycobacteria cultures were all negative. The latex agglutination test for Cryptococcus neoformans,Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitides andHaemophylus influenzae type B, and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for these bacteria as well as for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were also all negative. Blood cultures performed by automated microbiology growth and detection system for aerobic, anaerobic and fungi resulted negative. The patient underwent trepanation, and drainage of the lesion was performed. Purulent material was obtained and sent to culture, which resulted in the growth of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. Anti-Toxoplasma treatment was discontinued and antibiotic scheme was changed to oxacillin (2 g six times a day). The patient received eight weeks of this medication, improved progressively, clinically and radiologically (Fig. 1B-C) and was discharged to home. The patient underwent dental examination, with no evidence of dental infection. At transesophageal echocardiography the valves and left atrium were free of thrombi and vegetations, and there was no evidence of infection in thechest radiography and also in the abdominal ultrasound. In the daily assessment, measures of capillary glycemia were normal. Despite intensive efforts, no predisposing condition leading to the brain abscess, including trauma or surgery, intravenous drug use, skin or soft tissue infection, empyema, lung or intraabdominal abscess, bacterial endocarditis, dental infection, sinusitis or mastoiditis, were identified.

Fig. 1. - Evolution of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of an HIV-infected patient with a brain abscess due to Staphylococcus aureus. A , pre-trepanation CT showing a single expansive brain lesion in the left temporal area. B, after one week of trepanation, CT scan demonstrates a marked diminution in the size of the lesion, residual enhancement and a residual degree of edema. C , ten months after trepanation, CT scan reveals only post-surgical changes.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report a rare case of a brain abscess due to S. aureus in an HIV-infected patient.We found only two case reports of brain abscesses caused byStaphylococcus aureus in HIV-infected patients. The first case report has been criticized because the pathogen was isolated only from sputum cultures and skin samples, without any proof of the invasive disease such as the isolation of the bacterium from blood or from the brain abscess4. The second case reported an HIV-infected patient with a CD4 count of 85 cells/mm3, who presented an expansive lesion in the frontal lobe that did not show any improvement with empiric therapy for cerebral toxoplasmosis. Stereotactic biopsy of the lesion was performed and purulent material was found. Gram staining and culture revealed a methicillin-sensitive, cotrimoxazole-resistant S.aureus. Hematogenous dissemination from a cutaneous portal of entry was strongly suspected, because of a recent history of furunculosis5.

Current standard management for HIV-infected patients presenting with CNS mass lesions is to initiate empiric anti-toxoplasmosis therapy because CNS toxoplasmosis is the most frequent cause of HIV-associated intracranial lesions3 . The definitive diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis requires the presence of tachyzoites of the parasite in cerebral tissue6, but the availability and risks related to the brain biopsy precludes its routine use. Thus, if no clinical and radiological response is evident after 10 to 14 days of empiric therapy, other causes (infectious or non-infectious) should be considered7. It should be noted that if at admission or during the empirical treatment there is a high index of suspicion for an alternative diagnosis to cerebral toxoplasmosis, an early brain biopsy should be considered2.

In addition, it is important to consider other diagnoses than cerebral toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients under immunological and virological control, including etiologies of patients without HIV infection, for example, bacterial brain abscesses or tumors that are not related to immunossupression.

In ageneral population, bacterial brain abscesses can develop from three sources: first, because of the spread of infection from a pericranial contiguous focus (such as the sinuses, middle ear, or dental infection) in 25-50% of cases; second: from a distant focus of infection (such as a lung abscess or empyema, endocarditis, skin, or the intra-abdominal cavity), resulting in hematogenous spread in 15-30% of cases; and third, from a direct inoculation such as a head trauma or neurosurgery in 8-19% of cases8. The origin of brain abscess formation remains unknown (cryptogenic brain abscess) in 20-30% of cases8. In a general population, a wide range of pathogens can cause brain abscesses and Streptococci are the most common pathogens, comprising about 70% of isolates9 .

Staphylococcus aureus accounts for 10% 20% of isolates of brain abscesses in a general population, usually reported in patients with cranial trauma or endocarditis, and it is often isolated in culture. Some cases caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus have been reported. Population-based studies have identified male gender and very young and elderly individuals as being at increased risk for S. aureusinfections. Moreover, two studies showed that the most important risk factor is dialysis, either peritoneal (relative risk [RR], 150 to 204) or hemodialysis (RR, 257 to 291). Other conditions that increase the risk of invasive S. aureus infections include diabetes (RR, 7), cancer (RR, 7.1 to 12.9), rheumatoid arthritis (RR, 2.2 to 9.2), HIV infection (RR, 23.7), intravenous drug use (RR, 10.1), or alcohol abuse (RR, 8.2)10 , 11. However, one of the most important factors that is independently associated to brain abscess is chronic S. aureus nasal carriage12.

The status of HIV infection increases the chances of having invasive staphylococcal disease13, but it is difficult to establish a cause-effect relationship in the present case.

The purpose of this article is to highlight the need of timely diagnosis of expansive brain lesions in HIV-infected patients, including brain abscess, because it is a potentially fatal disease. Several studies have evaluated the findings of brain biopsies in the context of HIV infection and bacterial brain abscess contributes to a small percentage of the cases14 , 15 , 16, reinforcing the rarity of this medical condition in this setting.These studies highlight the utility of brain biopsy to uncover erroneous diagnostic hypotheses14.

In conclusion, although rare, S. aureus should be included in the differential diagnosis of expansive brain lesions in HIV-infected patients, despite the absence of classical risk factors to invasive disease caused by this bacterium. Timely neurosurgical procedure, adequate identification and susceptibility pattern of the microorganism, and an appropriate antibiotic, supported the favorable outcome in the present case.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vidal JE, Penalva de Oliveira AC. Lindoso JA, da Eira M, Casseb JS, Mello e Silva AC. Infectologia ambulatorial: diagnóstico e tratamento. São Paulo: Sarvier; 2008. Alterações neurológicas: parte I. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidal JE, Dauar RF, de Oliveira AC. Utility of brain biopsy in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome before and after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:e1209. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000315865.26706.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skiest JD. Focal neurological disease in patients with acquired immunode: ciency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:103–115. doi: 10.1086/324350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith NP, Nelson MR, Moore D, Gazzard BG. Cerebral abscesses in a patient with AIDS caused by methicillin-resistant Sthaphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:459–460. doi: 10.1258/0956462971920352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denoeud L, Pacanowski J, Welker Y, Moulignier A, Girard PM. Staphylococcus aureus brain abscess in an HIV-infected patient exposed to enfuvirtide. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2008;7:217–219. doi: 10.1177/1545109708323131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira-Chiocolla VL, Vidal JE, Su C. Toxoplasma gondii infection and cerebral toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:1363–1379. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skolasky RL, Dal Pan GJ, Olivi A, Lenz FA, Abrams RA, McArthur JC. HIV-associated primary CNS lymorbidity and utility of brain biopsy. J Neurol Sci. 1999;163:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathisen GE, Johnson JP. Brain abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:763–779. doi: 10.1086/515541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derber CJ, Troy SB. Head and neck emergencies: bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess, upper airway obstruction, and jugular septic thrombophlebitis. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:1107–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsson G, Dashti S, Wahlberg T, Anderson R. The epidemiology of and risk factors for invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections in western Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:6–13. doi: 10.1080/00365540600810026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laupland KB, Church DL, Mucenski M, Sutherland LR, Davies HD. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1452–1459. doi: 10.1086/374621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Rijen M, Bonten M, Wenzel R, Kluytmans J. Mupirocin ointment for preventing Staphylococcus aureus infections in nasal carriers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006216–CD006216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006216.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laupland KB, Ross T, Gregson DB. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: risk factors, outcomes, and the influence of methicillin resistance in Calgary, Canada, 2000-2006. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:336–343. doi: 10.1086/589717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gildenberg PL, Gathe JC, Jr, Kim JH. Stereotactic biopsy of cerebral lesions in AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:491–499. doi: 10.1086/313685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen CJ, Gjerris F, Pedersen H, Jensen FK, Wagn P. Brain biopsy in AIDS. Diagnostic value and consequence. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;127:99–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01808555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva AC, Rodrigues BS, Micheletti AM, Tostes S, Jr, Meneses AC, Silva-Vergara ML. Neuropathology of AIDS: an autopsy review of 284 cases from Brazil comparing the findings pre- and post-HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy) and pre- and postmortem correlation. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:186850–186850. doi: 10.1155/2012/186850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]