Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) represent abnormal aortal expansions that result from chronic proteolytic breakdown of elastin and collagen fibers by matrix metalloproteases. Poor elastogenesis by adult vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) limits regenerative repair of elastic fibers, critical for AAA growth arrest. Toward overcoming these limitations, we recently demonstrated significant elastogenesis by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived SMCs (BM-SMCs) and their proelastogenesis and antiproteolytic effects on rat aneurysmal SMCs (EaRASMCs). We currently investigate the effects of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (SPION) labeling of BM-SMCs, necessary to magnetically guide them to the AAA wall, on their functional benefits. Our results indicate that SPION-labeling is noncytotoxic and does not adversely impact the phenotype and elastogenesis by BM-SMCs. In addition, SPION-BM-SMCs showed no changes in the ability of the BM-SMCs to stimulate elastin regeneration and attenuate proteolytic activity by EaRASMCs. Together, our results are promising toward the utility of SPIONs for magnetic targeting of BM-SMCs for in situ AAA regenerative repair.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are localized, rupture-prone expansions of the abdominal aorta1 resulting from disruption of collagen and elastic fibers in the aortic wall by chronically overexpressed matrix metalloproteases (MMPs).2,3 There are no nonsurgical therapies to arrest growth of small AAAs. Although inhibiting MMPs may slow AAA growth,4 AAA growth arrest and restoration of vessel recoil properties are challenged by poor regenerative repair of elastic fibers by adult vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs).5–7 A proelastogenesis stimulus is thus needed that may be effective in the proteolytic AAA tissue milieu.

The involvement of stem cells and stem cell-derived SMCs in morphogenesis8 and tissue repair,9 the only physiologic events where robust vascular elastogenesis is observed, suggests their higher capacity for elastogenesis versus adult SMCs. Previously,10 we showed that rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BM-MSC)-derived SMCs (BM-SMCs) significantly stimulate synthesis of crosslinked elastic matrix and attenuate matrilysis in rat aneurysmal SMCs (EaRASMCs).10 We now seek to enable their targeted delivery to AAA tissue for regenerative benefit.

The rapid development of strong permanent magnet materials makes feasible magnetic targeting of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (SPION)-labeled cells to deep tissues in the human body, such as the aorta, even in the presence of high shear blood flow, and to track their retention and biodistribution using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—or computed tomography.11 As the first step, in this study, we assessed viability of SPION-labeled BM-SMCs, their responsiveness to an externally applied magnetic field for improved uptake into a matrix-disrupted aortic wall, and their ability to maintain their previously demonstrated functional benefits upon SPION-labeling.10

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of SMCs from elastase infusion-induced rat AAAs

Animal procedures were approved by the IACUC at the Cleveland Clinic. EaRASMCs were isolated from the infrarenal abdominal aortae of young adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (200 g) (n = 3) at 14-days post AAA induction by porcine pancreatic elastase (20 U/mL; Worthington) infusion.12 The AAA segments were harvested and minced and digested with type II collagenase (175 U/mL; Worthington) and porcine pancreatic elastase (3 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) to isolate the primary EaRASMCs.6 Primary cells from the three rats were pooled, passaged, and characterized.6 Similarly, control healthy rat aortic SMCs (RASMCs) were isolated from healthy adult rats (n = 3).6 The primary cells were cultured for 2 weeks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% v/v penicillin–streptomycin (Penstrep; Thermo Fisher) and passaged before use.

Differentiation of rat BM-MSCs into BM-SMCs

Rat BM-MSCs were differentiated into BM-SMCs using our published methods.10 BM-MSCs (Invitrogen; 2 × 104 cells/10-cm2) were cultured to confluence in low-glucose (1 g/L) DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% v/v MSC-qualified FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% v/v Penstrep. The cells were reseeded (2 × 104 cells/cm2) on human fibronectin-coated plastic (BD Biosciences), differentiated in a medium containing 2.5 ng/mL transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1; Peprotech) for 6 days, and then propagated for 5 days in high-glucose (4.5 g/L) DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% v/v FBS (Invitrogen), 1% v/v Penstrep, 2.5 ng/mL of TGF-β1, and 5 ng/mL of platelet derived growth factor (R&D Systems). The derived BM-SMCs were propagated in DMEM-F12 containing 10% v/v FBS and then passaged.

Labeling BM-SMCs with SPIONs

BM-SMCs were labeled with neutrally charged SPIONs (fluidMAG-D; mean diameter = 50 nm; Chemicell GmBH) per Riegler et al.13 BM-SMCs (3 × 104 cells/well) were cultured in six-well plates for 48 h, serum starved (2 h), and then incubated for 24 h in DMEM-F12 medium containing 10% v/v FBS, 375 ng/mL of poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich), and SPIONs (0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/mL).13–15

Assessing cell uptake and cytotoxicity of SPIONs

SPION-uptake by BM-SMCs was confirmed by Prussian blue staining.15,16 BM-SMCs were cultured on glass coverslips, labeled with SPIONs (0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/mL), washed, and incubated with an iron- and Nuclear Fast Red-stains (Scytek Labs). The cell layers were rinsed with a decreasing ethanol gradient and xylene, mounted with Entellan® (Merck KGaA), and visualized with light microscopy.

SPION effects on BM-SMC viability were assessed using the LIVE/DEAD® assay (Invitrogen)17; unlabeled BM-SMCs served as the control. The cells were visualized using fluorescence (Model IX51; Olympus America). The cytotoxicity of SPIONs was further confirmed by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay (Thermo Fisher).18 LDH activity in cells at the highest SPION dosage (1 mg/mL) was determined as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Determining magnetic responsiveness of SPION-labeled BM-SMCs

The responsiveness of SPION-BM-SMCs to a constant magnetic field gradient, applied orthogonal to gravity,19 was estimated using cell tracking velocimetry (CTV) as per Zborowski and colleagues.20 SPION-BM-SMCs (0.2, 0.5 and 1.0 mg/mL) were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/mL of culture medium. The cells were injected, using a 5-mL syringe connected to PEEK tubing, into the flow chamber (1.0 mm I.D, square borosilicate glass channel; Vitrocom) of the CTV apparatus (in the z-direction), perpendicular to gravity (x-direction). Valves on both sides of the flow chamber were closed and residual fluid motions allowed to completely dampen. SPION-BM-SMC motion within the flow chamber was recorded using a microscope with a 5× objective (Model BHMJ; Olympus). ImageView® software tracked the cells (400–1000/sample) between frames using algorithms to obtain a linear fit of location versus time data, to calculate velocities of individual cells. The magnetophoretic mobility of cells was calculated as cell velocity divided by the magnitude of the applied magnetic field gradient.19

Impact of magnetic targeting on BM-SMC uptake into vessel wall

Improved BM-SMC uptake into the vessel wall upon magnetic targeting was assessed ex vivo within matrix-disrupted porcine carotids (Lampire Biological Labs). The arteries were de-endothelialized using a guide wire, intraluminally infused with 20 U/mL porcine pancreatic elastase (Sigma-Aldrich) using a Scimed 5F catheter (SCIMED Life System) for 20 min at 37°C to disrupt the aortal elastic matrix, and then rinsed with sterile PBS.

SPION-BM-SMCs (1 × 106 cells/mL) were labeled with VivoTrack 680 (Perkin Elmer; 0.5 mg/mL, 15 min) and then infused into the carotid lumen at 15 × 106 cells/mL using a Scimed 5F catheter, with the distal end clamped. BM-SMCs were infused into control carotids. The test artery alone was exposed to a permanent NdFeB magnet (CMS Magnetics) for 40 min.13 The arteries were then flushed repeatedly with PBS to remove loosely adherent cells. Image J® analysis of whole tissue images (Bruker Xtreme®) quantified relative fluorescence across the vessel length. Results were plotted as mean fluorescence versus axial distance from point of cell infusion. The carotids were opened lengthwise and fluorescence signal distribution visualized using a laser-based scanning system (LI-COR Odyssey®).

Impact of SPION-labeling on phenotype and elastogenesis by BM-SMCs

SPION-labeled (0.5 mg/mL) and -unlabeled BM-SMCs were cultured in six-well plates (3 × 104 cells/well) for 14 and 21 days, respectively, for comparing their phenotype (real time–polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR], western blot) and elastogenesis (Fastin assay) as described subsequently.

Impact of SPION-labeling on paracrine effects of BM-SMCs on cocultured EaRASMCs

The paracrine effects of SPION-labeled and -unlabeled BM-SMCs on elastogenesis by EaRASMCs were determined in transwell cocultures.10 EaRASMCs were seeded within wells of six-well plates (3 × 104 cells/well) and maintained for 21 days in standalone culture (control) or in noncontact coculture with BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs similarly seeded within PET-transwell inserts (pore size = 1 μm; Greiner Bio-One). The EaRASMCs were subsequently harvested for analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

RT-PCR assessed the gene expression profile in (1) BM-SMCs upon SPION-labeling and (2) EaRASMCs upon coculture with SPION-labeled and -unlabeled BM-SMCs.13,14 We investigated SMC-phenotypic marker protein genes (α-smooth muscle actin [ACTA2], caldesmon [CALD1], smoothelin [SMTN], and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain [MYH11]), genes for proteins involved in elastic fiber assembly (tropoelastin [ELN], fibrillin-1 [FBN1], lysyl oxidase [LOX], fibulin-4 [EFEMP2], fibulin-5 [FBLN5]), and genes for elastolytic MMPs (MMP2 and MMP9), collagen type I (COL1A1), and tissue inhibitors of MMP1 (TIMP-1). Cell layers were analyzed at 14 days (SPION-BM-SMCs vs. BM-SMCs and RASMCs) or 21 days (EaRASMCs cultured standalone vs. in coculture with SPION-BM-SMCs or BM-SMCs) of culture. RNA was isolated, quantified, and RT-PCR was carried out on equal amounts of RNA reverse transcribed, as published21–23; primer sequences are indicated in Table 1. Results were analyzed by a linear regression of efficiency method24 using a Matlab code.25 The resulting copy number for each group was normalized to its corresponding 18s ribosomal RNA (18S) and reported as relative fluorescence units (RFU).

Table 1.

List of Primer Sequences of Genes for SMC Marker Proteins and Proteins Involved in Elastic Fiber Assembly and Homeostasis

| Gene | Forward primer (5′→ 3′) | Reverse primer (5′→ 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 18S | CGGACAGGATTGACAGAT TG | ACG CCA CTT GTC CCT CTA AG |

| ACTA2 | ATAGAACACGGCATCATCAC | GTCTCAAACATAATCTGGGTC |

| CALD1 | GAGAGGAGGAAGAGAAGAGGA | CACTTGAACGGCTTCTTGTC |

| MYH11 | TGCTACAAGATCGTGAAGAC | CTTTCTTGCCTTTGTGGGAG |

| SMTN | GCCTGGACTGTAGTCTCCAA | AGCTCAGCCTCCATTAGGTT |

| ELN | CCTGGTGGTGTTACTGGTATTGG | CCGCCTTAGCAGCAGATTTGG |

| LOX | AGACGATTTGCCTGTACTGC | ATAGGCGTGATGTCCTGTGT |

| FBN1 | ATAAATGAATGTGCCCAGAATCCC | ACTCATCCTCATCTTTACACATCC |

| EFEMP2 | GGCTCTGCCAAGACATTGTA | GACACTTGGACATAGGGCTC |

| FBLN5 | CGAGGGTCGAGAGTTCTACA | CAGAACGGATACTGGGACAC |

| COL1A1 | CAGGGCGAGTGCTGTCCTT | GGTCCCTCGACTCCTATGACTTC |

| MMP2 | GGAGCGACGTAACTCCACTA | AAGTGAGAATCTCCCCCAAC |

| MMP9 | ACTTCTGGCGTGTGAGTTTC | TGTATCCGGCAAACTAGCTC |

| TIMP1 | CATGGAGAGCCTCTGTGGAT | ATGGCTGAACAGGGAAACAC |

SMC, smooth muscle cells.

Western blots

Differences in synthesis of SMC phenotype marker proteins between BM-SMC groups and also MMP2 protein by EaRASMCs in standalone culture or in cocultures were semi-quantitatively analyzed by western blotting.10,17 Primary antibodies for SMA, SM22, Smoothelin, MHC, MMP2 (Abcam), MMP9 (Millipore), and the housekeeping protein β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Secondary antibodies were conjugated with either IRDye® 680LT or IRDye® 800CW (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein bands were visualized on an LI-COR Odyssey laser-based scanning system, quantified using ImageJ software, and normalized to respective β-actin bands and further to the ratio obtained for cell controls (RASMCs for SPION-labeling and EaRASMCs in paracrine effect studies).

DNA assay for cell proliferation

A fluorometric DNA assay26 determined effects of SPION-labeling on (1) BM-SMC proliferation versus RASMCs and on (2) their paracrine effects on proliferation of cocultured EaRASMCs versus standalone EaRASMC controls. Cell counts were estimated assuming 6 pg of DNA per cell.26

Fastin assay for elastin

Tropoelastin secreted into the medium conditioned by EaRASMCs within the wells and total elastic matrix deposited by control and cocultured EaRASMCs over 21 days were quantified using a Fastin assay (Accurate Chemical and Scientific).10,17,27 Hot oxalic acid digestion extracted soluble elastin from equal volumes of the harvested homogenized cell layers. Elastic matrix amounts measured in the extracts with the Fastin assay were normalized to the corresponding cell numbers in each group.

Immunofluorescence visualization of elastic matrix

Standalone and cocultured EaRASMC layers (21 days) were fixed in cold methanol and treated with an antibody against elastin (Millipore). Elastic matrix was visualized with an Alexa488-conjugated IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Cell layers were mounted with Vectashield® containing DAPI (Vector Labs) and were imaged using a fluorescence microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) compared elastic matrix ultrastructure between standalone and cocultured EaRASMC layers. As we previously published,6,7 21-day cultures within Permanox chamber slides were fixed with 2% w/v cacodylate glutaraldehyde (12 h), postfixed in 1% w/v osmium tetroxide (1 h), dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (50–100% v/v), and embedded in Epon 812 resin. The sections were mounted on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and visualized on a Hitachi TEM (Model H7600T).

Gel zymography

Differences in enzyme activities of MMP2 and 9 between standalone (control) and cocultured EaRASMC groups were assessed by gel zymography.10,17 The MMP2 and 9 band intensities in the test cultures were normalized to that in controls for comparison.

Statistical analysis

Values shown are mean ± standard deviation (SD) from n = 6 replicate cultures/condition. A total of n = 3 replicate cultures/condition were analyzed for western blotting, gel zymography, TEM, and immunofluorescence (IF) imaging. The number of replicates was determined by power analysis28 of our prior data7 with cell cultures, which indicated that n = 6 replicates for biochemical assays and n = 3 replicates for western blot and zymography analyses, with three independent measurements for each parameter, sufficient to reliably detect quantitative differences in outcomes, with a power of ≥0.95. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Fisher's LSD post hoc test, and differences between groups deemed statistically significant for p-values <0.05.

Results

Impact of SPION-labeling on BM-SMCs

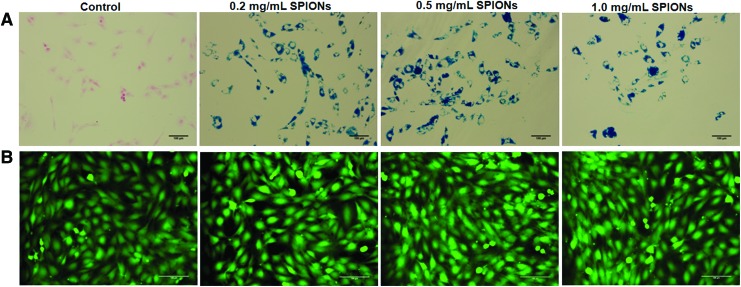

Prussian blue staining indicated significant SPION uptake by BM-SMCs at all three tested SPION concentrations, but no coloration in controls (Fig. 1A); no SPION dose-dependent differences in uptake were noted. At all SPION-labeling doses, most BM-SMCs remained viable (green; Fig. 1B). Even at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL), SPIONs were noncytotoxic to BM-SMCs (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec).

FIG. 1.

Prussian blue staining of BM-SMCs (A) indicates successful uptake of SPIONs at all tested concentrations, as determined by the amount of blue stain around the pink-stained nucleus. LIVE/DEAD staining (B) shows no adverse effects of SPION-labeling on BM-SMCs, as confirmed by green fluorescence of viable cells. Scale bars = 100 μm. BM-SMCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived SMCs; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; SPION, super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

SPION-BM-SMCs were significantly mobile even under the weak applied magnetic field (Table 2), while unlabeled BM-SMCs were immobile. Magnetic velocity of the labeled BM-SMCs increased as a function of SPION dose only up to 0.5 mg/mL; still higher SPION dosing (1 mg/mL) did not increase magnetic velocity further (p = 0.143 vs. 0.5 mg/mL).

Table 2.

CTV Analysis Showing Increased Magnetic Mobility for SPION-BM-SMCs at 0.5 and 1.0 mg/mL SPION Concentrations

| Sample (SPION conc.) | Magnetic velocity (mm/s) |

|---|---|

| SPION-BM-SMC (0.2 mg/mL) | 0.025 ± 0.013 |

| SPION-BM-SMC (0.5 mg/mL) | 0.028 ± 0.012 |

| SPION-BM-SMC (1.0 mg/mL) | 0.029 ± 0.011 |

| Unlabeled BM-SMC | 0 |

Shown are mean ± SD of values obtained from n = 500–700 cells/sample.

BM-SMC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived SMC; CTV, cell tracking velocimetry; SD, standard deviation; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; SPION, super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle.

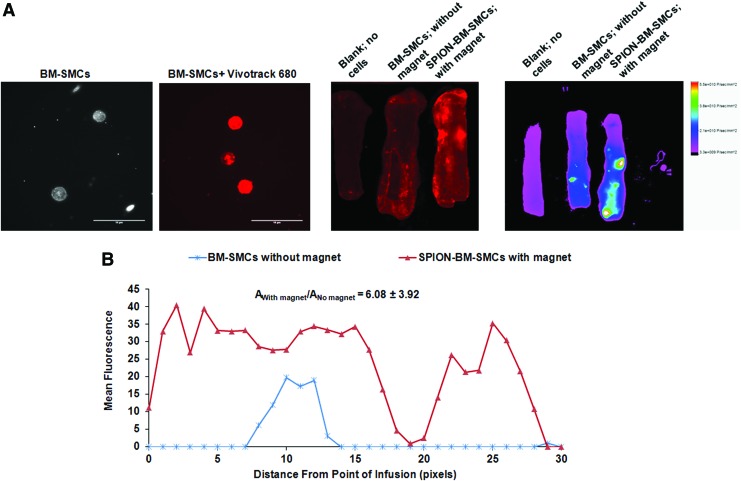

SPION-BM-SMCs infused in the presence of an adjoining permanent magnet showed significantly higher fluorescence indicating higher uptake and retention in the wall of matrix-disrupted porcine carotids versus unlabeled BM-SMCs infused in the absence of an applied magnetic field, while vessels not infused with any cells showed no fluorescence beyond the background (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

SPION-labeling of BM-SMCs in conjunction with an applied magnetic field significantly increases uptake and retention of the cells into matrix-disrupted porcine carotids upon ex vivo infusion. Representative images show successful BM-SMC labeling with infrared emitting fluorescent tracker dye (Vivotrack 680), (A) distribution of Vivotrack 680-labeled BM-SMCs (without magnet) or SPION-BM-SMCs (with magnet) within porcine carotid arteries as viewed using an Odyssey scanning system, (B) and a Bruker whole tissue imaging system (C). Quantitative analysis (D) of whole tissue image (C) showing the mean fluorescence intensities in carotids with BM-SMCs or SPION-BM-SMCs corrected for background relative to carotid with no cells (blank). Fold differences in area under the curves represented as mean ± SD values from n = 3 carotids/case indicate significant retention of SPION-BM-SMCs in presence of magnet compared to BM-SMCs without magnet. Scale bars = 10 μm. SD, standard deviation. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

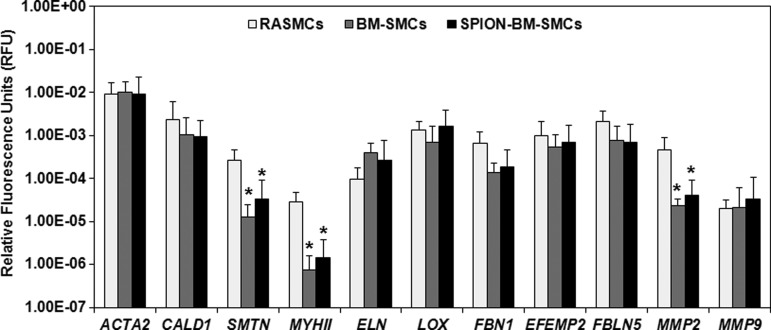

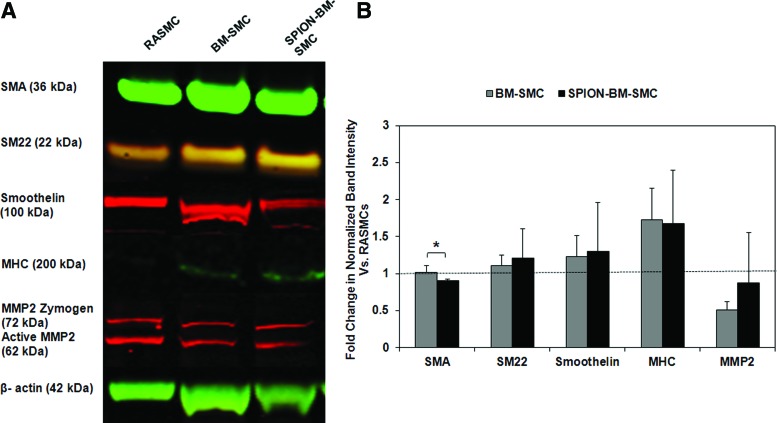

BM-SMC expression of genes for SMC-phenotypic markers and elastic matrix assembly proteins was unaltered (p >0.05) by SPION-labeling (Fig. 3); in both BM-SMC groups, SMTN and MYHII expression were significantly lower (p <0.05) than for RASMCs. Except for FBN1 and MMP2, expression of other genes for proteins involved in elastin homeostasis was higher in the BM-SMC cultures versus RASMCs. SPION-labeling did not alter BM-SMC synthesis of SMC phenotypic marker proteins except for SMA, which was lower in the SPION-BM-SMC cultures (p = 0.040; Fig. 4). There was also no significant difference in the β-actin-normalized protein amounts of SMA, SM22, and smoothelin for either BM-SMC group relative to RASMCs.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR outcomes showing similar expression levels of genes for SMCs and elastic matrix homeostatic markers by both SPION-BM-SMCs (0.5 mg/mL SPIONS) and unlabeled BM-SMCs. Expression levels of all genes were normalized to expression of a reference gene (18S) and indicated as mean ± SD of RFU from n = 6 replicate cultures/condition. * indicates significant differences in gene expression between BM-SMCs or SPION-BM-SMCs versus RASMCs, deemed for p < 0.05. RAMSC, rat aortic SMCs; RFU, relative fluorescence unit; RT-PCR, real time–polymerase chain reaction.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis shows no difference in expression of SMC marker proteins and elastolytic MMP2 between unlabeled BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs. Shown are (A) representative image of western blot with β-actin as loading control and (B) fold changes of band intensities normalized to β-actin relative to ratios obtained for RASMCs (positive control) from n = 3 replicate cultures/condition. Immature SMC-like characteristics of BM-SMCs were retained upon SPION-labeling as determined from high expression of early and midstage markers (SMA and SM22) and weaker expression of terminal differentiation marker (MHC) relative to RASMCs. * indicates significant differences between BM-SMCs or SPION-BM-SMCs versus RASMCs, deemed for p < 0.05. MMP, matrix metalloproteases. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

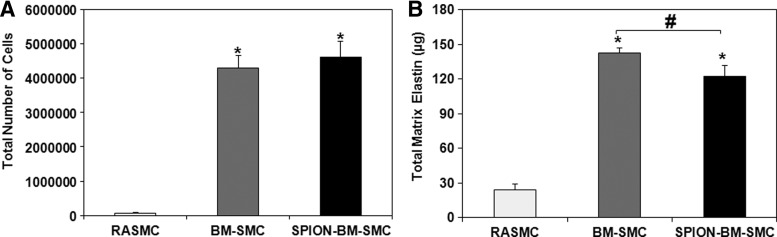

SPION-labeling did not alter the proliferation of BM-SMCs (p = 0.115 for BM-SMCs vs. SPION-BM-SMCs) (Fig. 5A). Absolute amounts of elastic matrix generated by SPION-BM-SMCs were slightly lower compared to BM-SMCs (p = 0.0001; Fig. 5B), although elastic matrix amounts generated on a per cell basis were similar (p = 0.81).

FIG. 5.

SPION-labeling modestly alters proliferation (A) and elastic matrix synthesis (B) in BM-SMC cultures. Values shown indicate mean ± SD values measured in n = 6 replicate cultures/condition at 21-day cultures. * and # indicate significant differences between BM-SMCs or SPION-BM-SMCs versus RASMCs and BM-SMCs versus SPION-BM-SMCs, respectively, deemed for p < 0.05.

Paracrine effects of BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs on EaRASMCs

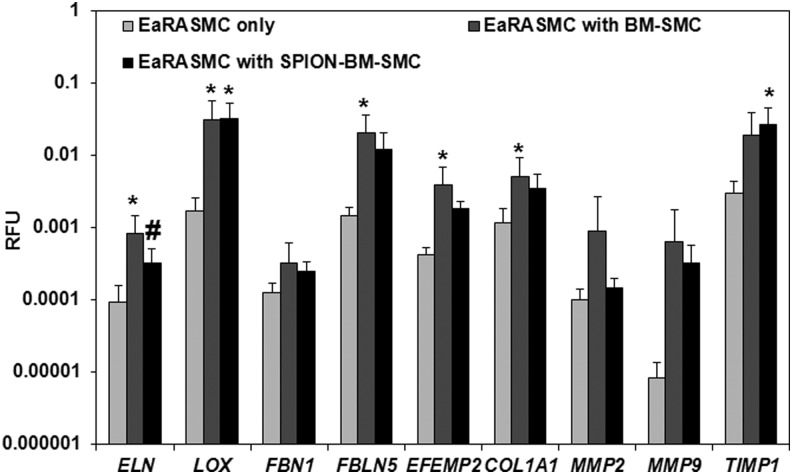

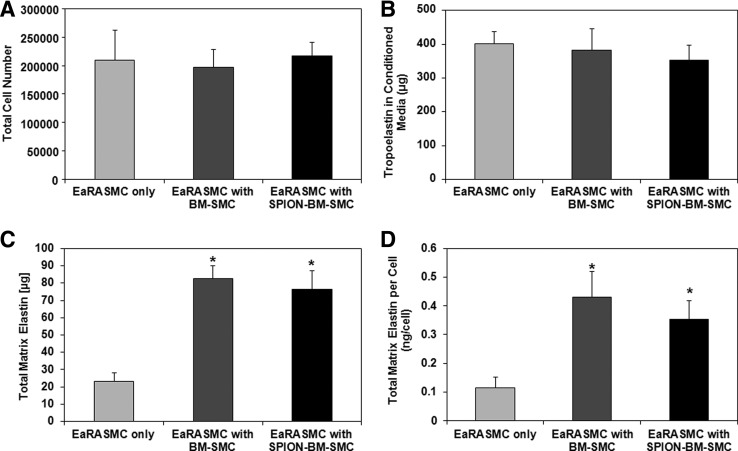

Relative to control EaRASMCs, ELN, LOX, FBLN5, EFEMP2, and COL1A1 expression were significantly higher (p = 0.005, 0.016, 0.005, 0.005, 0.020) in EaRASMCs cocultured with BM-SMCs, while only LOX and TIMP1 were significantly higher (p = 0.012, 0.018) in EaRASMCs cocultured with SPION-BM-SMCs (Fig. 6). There were no differences in expression of elastic fiber assembly protein genes except for ELN (Fig. 6), which was slightly lower in EaRASMCs cocultured with SPION-BM-SMCs (p = 0.04). Expression of MMP genes was similar in all three EaRASMC groups (Fig. 6). Proliferation and tropoelastin synthesis were not different between control and cocultured EaRASMCs and between the cocultured EaRASMCs (Fig. 7A, B). Elastic matrix amounts deposited by the cocultured EaRASMCs were significantly higher than that by control EaRASMCs (p = 0.0001 and 0.0001 vs. BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs), both on an absolute (Fig. 7C) and a cell-normalized basis (Fig. 7D), but were not different between the two groups of cocultured EaRASMCs.

FIG. 6.

RT-PCR analysis shows increased expression of genes for elastic matrix assembly proteins by EaRASMCs cultured with BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs in real time, relative to controls (standalone EaRASMCs). No differences in gene expression were noted between EaRASMCs cocultured with BM-SMCs or SPION-BM-SMCs except for ELN. Indicated are the mean ± SD of RFU normalized to reference gene (18S) obtained by analysis of n = 6 replicate cultures/condition. * and # indicate significant differences between cocultured and control EaRASMCs and between EaRASMCs cocultured with BM-SMCs versus EaRASMCs with SPION-BM-SMCs, respectively, deemed for p < 0.05. EaRASMCs, elastic matrix and attenuate matrilysis in rat aneurysmal SMCs.

FIG. 7.

Paracrine effects of BM-SMCs on EaRASMC proliferation and matrix synthesis are unaltered by their labeling with SPIONs. Shown are proliferation ratios (A), tropoelastin amounts in spent media (B), total elastic matrix amounts in cell layers (C), and total matrix elastin synthesized on a per cell basis (D). Values shown represent mean ± SD of outcomes measured from n = 6 replicate cultures/condition at 21 days of culture. * indicates significant differences between standalone EaRASMCs versus cocultured EaRASMCs, deemed for p < 0.05.

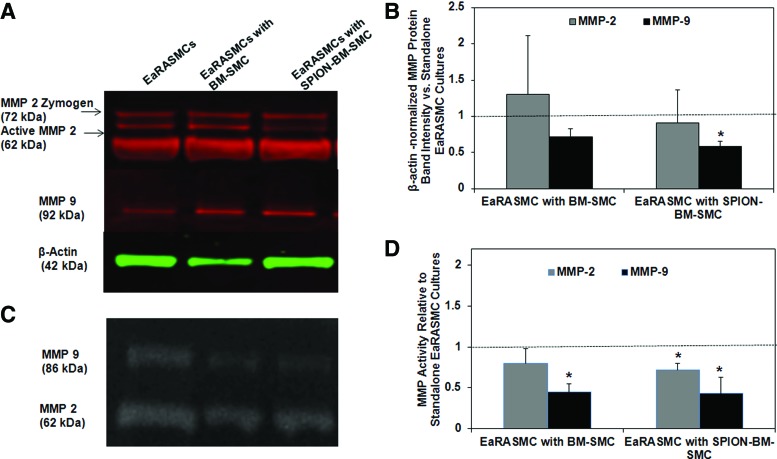

Both SPION-labeled and-unlabeled BM-SMCs had no inhibitory effect on MMP2 protein synthesis by EaRASMCs (Fig. 8A) versus control, but significantly reduced MMP9 synthesis (p = 0.049 for SPION-BM-SMCs vs. control); no differences in MMP synthesis were noted between the cocultured EaRASMC groups. While only MMP9 activity was significantly reduced in EaRASMC layers cocultured with BM-SMCs (p = 0.004), both MMP2 and MMP9 activities were reduced in EaRASMCs cocultured with SPION-BM-SMCs (p = 0.038 and 0.003, respectively) (Fig. 8B). MMP activities were not different between the two groups of cocultured EaRASMCs.

FIG. 8.

Antiproteolytic effects of BM-SMCs on EaRASMCs are maintained upon SPION-labeling. Shown are MMP2 and 9-protein synthesis and enzyme activity in EaRASMC cultures, as analyzed by western blots and gelatin zymography, respectively. (A) Representative image of western blot with β-actin as loading control. (B) Fold changes in intensities of zymogen and active MMP2 & 9 bands (normalized to corresponding β-actin loading control bands) in western blots relative to standalone EaRASMC cultures (controls) (n = 3 cultures/condition; indicated as dotted line). (C) Representative image of gel zymogram for MMP2 & 9. (D) Plot comparing mean ± SD of fold changes in active MMP2 & 9 band intensities in the zymograms, versus control EaRASMC cultures (n = 3 cultures/condition). * indicates significant differences between EaRASMCs in coculture versus standalone EaRASMC cultures, deemed for p < 0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

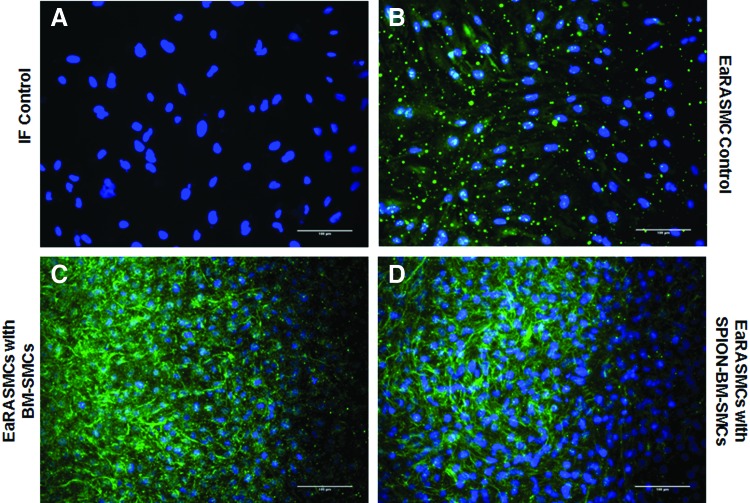

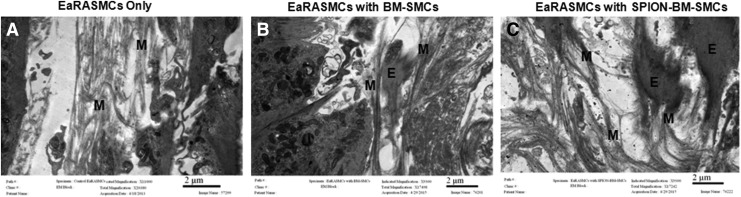

IF showed significantly greater deposition of elastic matrix (green) by cocultured EaRASMCs versus controls and no noticeable differences were noted in this outcome between the two cocultured groups (Fig. 9). TEM images (Fig. 10) showed nascent fiber formation with large amorphous elastin deposits in both EaRASMC layers cocultured with BM-SMCs (Fig. 10B) and SPION-BM-SMCs (Fig. 10C), unlike in standalone EaRASMC controls (Fig. 10A).

FIG. 9.

(A) Confocal overlay images of IF-stained EaRASMC layers indicate increased deposition of elastic matrix (green) by EaRASMCs upon noncontact coculture with both BM-SMCs (C) and SPION-BM-SMCs (D) versus standalone EaRASMC cultures (B; control). DAPI-stained nuclei appear blue. All cell layers were imaged at 21 days. Scale bars = 100 μm. IF, immunofluorescence. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 10.

Transmission electron microscopy images showing that increased elastic matrix deposition by EaRASMCs upon coculture with unlabeled BM-SMCs is maintained upon coculture with SPION-BM-SMCs. Microfibrillar structures ‘M’ were observed in control (A), while significant amount of elastin deposits ‘E’ associated with ‘M’ were observed in EaRASMC cocultures with BM-SMCs (B) and SPION-BM-SMCs (C) at 21 days in culture. Scale bars = 2 μm.

Discussion

AAA growth occurs due to chronic enzymatic breakdown of the wall structural matrix. Unlike collagen fibers, which undergo natural regenerative repair postdisruption, elastic fibers are poorly restored, due to poor elastogenesis, and impaired elastic fiber assembly by postneonatal and diseased vascular SMCs.6,7,29,30 Thus, to achieve AAA growth arrest, elastin regeneration must significantly exceed its breakdown.31

Previously,10 we showed that BM-SMCs exhibit high elastogenesis and generate paracrine secretions that stimulate elastogenesis by EaRASMCs, findings which support their use for matrix regenerative AAA therapy, provided they can be efficiently delivered to the AAA wall. One way to achieve this is by guiding intra-aortally infused, magnetically responsive BM-SMCs into the AAA wall using an externally applied magnetic field. The BM-SMCs are rendered paramagnetic by SPION-labeling,13–32,33 a strategy that has been applied to cell delivery to other tissue locations and facilitates their tracking using MRI.34–36 In the context of our proposed use of BM-SMCs, in this study, we sought to ascertain how SPION-labeling influences phenotype and functionality of the BM-SMCs, including their proelastogenesis and antiproteolytic properties.10

Since nanoparticles (1) smaller than 100 nm37 and (2) bearing a cationic charge38 can be more cytotoxic to nonphagocytic cells, we labeled BM-SMCs with fluidMAG-D nanoparticles of size >100 nm, which contain starch as a polymer matrix and present surface hydroxyl (-OH) groups that are neutral at physiologic pH.39 The concentration of SPIONs (0.2, 0.5, 1.0 mg/mL) was selected based on the study conducted by Reigler et. al, where they showed the potential cytotoxicity of SPIONs beyond 1 mg/mL dosage.13 Since the size and neutral charge of our SPIONs can limit their uptake by BM-SMCs,40 we used poly-L-lysine as a cationic agent that facilitates SPION uptake,14 as confirmed in Figure 1. Since the SPIONs are neutrally charged, they do not induce intracellular lysosomal damage and cellular apoptosis, as with anionic nanoparticles.41 CTV analysis, which is a reliable measure of magnetic mobility, showed that our SPION-BM-SMCs have significant magnetic mobility even under the weak applied magnetic field (B = 0.1 Tesla) & field gradient (dB/dZ = 0.078 Tesla/cm) conditions, unlike unlabeled BM-SMCs. Thus, when this technology is clinically translated, the strong magnetic fields (∼3 Tesla) applied using commercial MRI scanner systems are expected to provide a strong driving force to efficiently draw intra-aortally infused SPION-BM-SMCs to the AAA wall.13 The plateauing of the magnetic velocity of the SPION-BM-SMCs beyond a 0.5 mg/mL SPION-labeling dose (Table 2) suggests that it is limited by the strength of the applied magnetic field.

Whole tissue imaging showed significantly greater uptake and retention of SPION-BM-SMCs into matrix-disrupted arteries in the presence of an adjoining permanent magnet (Fig. 2C), relative to uptake of nonlabeled BM-SMCs, which confirmed utility of SPION-labeling for the purpose. However, BM-SMC-associated fluorescence was not uniform across circumference of the artery lumen, likely because the magnet did not uniformly surround the vessel. While the emphasis in this study was not on magnet design and magnetic field optimization, we will systematically investigate these aspects in future. The lack of decrease in SPION-BM-SMC-associated fluorescence in the test vessels, despite repeat luminal flushing with PBS, suggests that the cells are not superficially adhered to the luminal wall, but instead distributed within the wall tissue. Such cell penetration into the wall tissue likely occurs through gaps in the endothelium and the disrupted extracellular matrix caused by elastase injury.

SMCs express distinct maturation stage-specific phenotypic marker proteins.8 For this reason, we investigated BM-SMC expression of markers characteristic of early (SMA), mid (SM22α, caldesmon), and late (MHC) stages of maturation leading to a terminally differentiated state. Our gene expression studies showed that BM-SMCs do not exhibit a mature terminally differentiated phenotype42,43 and are not phenotypically changed by SPION-labeling. The intermediate maturation state of our BM-SMCs likely accounts for their higher elastogenesis versus RASMCs as is the case with neonatal vascular SMCs.5 Despite the lower gene expression of terminal SMC differentiation markers by BM-SMCs, differences in synthesis of these same marker proteins were not different than in RASMCs (Fig. 3); closer inspection of this data suggests that this might be due to large SDs associated with analysis with a relatively small number of replicate samples (n = 3).

Our results indicate that SPION-labeling of BM-SMCs does not adversely impact their expression of ELN or capacity for elastic matrix neoassembly. Since ELN expression and elastic matrix synthesis per cell (0.343 ± 0.079 ng/cell for RASMCs vs. 0.033 ± 0.002 ng/cell for BM-SMCs and 0.026 ± 0.003 ng/cell for SPION-BM-SMCs) by BM-SMCs were similar to RASMCs, their significantly higher generation of elastic matrix (Fig. 5B) is likely due to their faster proliferation versus terminally differentiated and quiescent RASMCs.8 The interim differentiation state of BM-SMCs, similar to neonatal vascular SMCs, likely account for their more rapid proliferation.44 Overall, our ability to generate significantly greater net amounts of elastic matrix with the use of BM-SMCs versus RASMCs, for identical seeding counts, justifies their proposed use for regenerative AAA therapy.

We investigated how SPION-labeling impacts the proelastogenesis stimuli from BM-SMC secretions on EaRASMCs.10 In general, while SPION-labeling of BM-SMCs did not significantly change the upregulated expression of almost all tested elastic matrix assembly genes by cocultured EaRASMCs, only the changes in expression of LOX and TIMP1 were statistically higher than in EaRASMC controls. While increased LOX implies possible increases in tropoelastin crosslinking45 and increased FBLN5 and EFEMP2 expression suggest increased tropoelastin association with glycoprotein microfibrils for improved elastic fiber formation,46 the increase in TIMP1 suggests greater regulation of MMP activity. Collectively, the outcomes suggest that BM-SMCs even when labeled with SPIONs would provide an impetus to improving quantity and quality of elastic matrix assembly in a proteolytic milieu.

Again, despite slight differences in ELN expression between EaRASMCs cocultured with the BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs (Fig. 6), no differences were seen in amounts of tropoelastin measured in the wells (Fig. 7), which we confirmed (data not shown) to be exclusively generated by the EaRASMCs and not generated by the SPION-BM-SMCs and BM-SMCs within the transwell inserts. This in turn suggests that BM-SMC- and SPION-BM-SMC-derived secretions have similar effects on elastogenesis by EaRASMCs. This lack of differences in tropoelastin synthesis in cocultured EaRASMCs versus control EaRASMCs despite lower ELN in the latter suggests that one or more posttranscriptional steps leading to extracellular tropoelastin release likely limit tropoelastin precursor yield. Significantly higher elastic matrix deposition in EaRASMC cocultures relative to controls also suggests augmentation of posttranslational matrix assembly processes (e.g., precursor recruitment, microfibril engagement, and crosslinking) in the cocultures.

Outcomes of IF and TEM imaging (Figs. 9 and 10) were mostly consistent with the biochemical assay outcomes in showing significantly greater number of mostly nascent elastic fibers in the cocultured EaRASMC layers than in control cultures and no apparent differences in density and form of elastic matrix between EaRASMCs cocultured with BM-SMCs and SPION-BM-SMCs. Our data also indicate that MMP synthesis and proteolytic activity in BM-SMC cultures are not increased upon labeling the cells with SPIONs, and their anti-MMP effects are retained upon SPION-labeling (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that SPION-labeling of BM-SMCs, necessary to render them magnetically responsive for magnetic field-guided delivery to the AAA wall, does not adversely impact their viability, phenotype, elastic matrix synthesis, and elastogenesis-stimulatory and antiproteolytic properties. With this evidence in hand, future work will focus on optimizing magnetic field parameters for efficient BM-SMC delivery to AAA tissue toward assessing their efficacy for regenerative matrix repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge research funding for this project from the National Institutes of Health (HL092051), American Heart Association (13GRNT17080027), and National Science Foundation (BME Division; 1508642) awarded to A.R.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Selle J.G., Robicsek F., Daugherty H.K., and Cook J.W. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. A review and current status. Ann Surg 189, 158, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vine N., and Powell J.T. Metalloproteinases in degenerative aortic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 81, 233, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irizarry E., Newman K.M., Gandhi R.H., Nackman G.B., Halpern V., Wishner S., Scholes J.V., and Tilson M.D. Demonstration of interstitial collagenase in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease. J Surg Res 54, 571, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrinec D., Liao S.X., Holmes D.R., Reilly J.M., Parks W.C., and Thompson R.W. Doxycycline inhibition of aneurysmal degeneration in an elastase-induced rat model of abdominal aortic aneurysm: preservation of aortic elastin associated with suppressed production of 92 kD gelatinase. J Vasc Surg 23, 336, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson D.J., Robson P., Hew Y., and Keeley F.W. Decreased elastin synthesis in normal development and in long-term aortic organ and cell cultures is related to rapid and selective destabilization of mRNA for elastin. Circ Res 77, 1107, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gacchina C.E., Deb P., Barth J.L., and Ramamurthi A. Elastogenic inductability of smooth muscle cells from a rat model of late stage abdominal aortic aneurysms. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 1699, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gacchina C., Brothers T., and Ramamurthi A. Evaluating smooth muscle cells from CaCl2-induced rat aortal expansions as a surrogate culture model for study of elastogenic induction of human aneurysmal cells. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 1945, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owens G.K., Kumar M.S., and Wamhoff B.R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 84, 767, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han D.K.M., and Liau G. Identification and characterization of developmentally regulated genes in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 71, 711, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swaminathan G., Gadepalli V.S., Stoilov I., Mecham R.P., Rao R.R., and Ramamurthi A. Pro-elastogenic effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived smooth muscle cells on cultured aneurysmal smooth muscle cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2014. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/term.1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azene N., Fu Y., Maurer J., and Kraitchman D.L. Tracking of stem cells in vivo for cardiovascular applications. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 16, 7, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anidjar S., Salzmann J.L., Gentric D., Lagneau P., Camilleri J.P., and Michel J.B. Elastase-induced experimental aneurysms in rats. Circulation 82, 973, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riegler J., Liew A., Hynes S.O., Ortega D., O'Brien T., Day R.M., Richards T., Sharif F., Pankhurst Q.A., and Lythgoe M.F. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle targeting of MSCs in vascular injury. Biomaterials 34, 1987, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babic M., Horak D., Trchova M., Jendelova P., Glogarova K., Lesny P., Herynek V., Hajek M., and Sykova E. Poly(L-lysine)-modified iron oxide nanoparticles for stem cell labeling. Bioconjug Chem 19, 740, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jasmin , Torres A.L., Nunes H.M., Passipieri J.A., Jelicks L.A., Gasparetto E.L., Spray D.C., Campos de Carvalho A.C., and Mendez-Otero R. Optimized labeling of bone marrow mesenchymal cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and in vivo visualization by magnetic resonance imaging. J Nanobiotechnology 9, 1477, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasmin , Torres A.L., Jelicks L., de Carvalho A.C., Spray D.C., and Mendez-Otero R. Labeling stem cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: analysis of the labeling efficacy by microscopy and magnetic resonance imaging. Methods Mol Biol 906, 239, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivaraman B., and Ramamurthi A. Multifunctional nanoparticles for doxycycline delivery towards localized elastic matrix stabilization and regenerative repair. Acta Biomater 9, 6511, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Briz V., Chishti A., Bi X., and Baudry M. Distinct roles for mu-calpain and m-calpain in synaptic NMDAR-mediated neuroprotection and extrasynaptic NMDAR-mediated neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 33, 18880, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jing Y., Mal N., Williams P.S., Mayorga M., Penn M.S., Chalmers J.J., and Zborowski M. Quantitative intracellular magnetic nanoparticle uptake measured by live cell magnetophoresis. FASEB J 22, 4239, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCloskey K.E., Comella K., Chalmers J.J., Margel S., and Zborowski M. Mobility measurements of immunomagnetically labeled cells allow quantitation of secondary antibody binding amplification. Biotechnol Bioeng 75, 642, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bashur C.A., and Ramamurthi A. Aligned electrospun scaffolds and elastogenic factors for vascular cell-mediated elastic matrix assembly. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 6, 673, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bashur C.A., and Ramamurthi A. Composition of intraperitoneally implanted electrospun conduits modulates cellular elastic matrix generation. Acta Biomater 10, 163, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kothapalli C.R., Taylor P.M., Smolenski R.T., Yacoub M.H., and Ramamurthi A. Transforming growth factor beta 1 and hyaluronan oligomers synergistically enhance elastin matrix regeneration by vascular smooth muscle cells. Tissue Eng 15, 501, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutledge R.G., and Stewart D. A kinetic-based sigmoidal model for the polymerase chain reaction and its application to high-capacity absolute quantitative real-time PCR. BMC Biotechnol 8, 1472, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leigh D.R., Mesiha M., Baker A.R., Walker E., and Derwin K.A. Host response to xenograft ECM implantation is not different between the shoulder and body wall sites in the rat model. J Orthop Res 30, 1725, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labarca C., and Paigen K. A simple, rapid, and sensitive DNA assay procedure. Anal Biochem 102, 344, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sylvester A., Sivaraman B., Deb P., and Ramamurthi A. Nanoparticles for localized delivery of hyaluronan oligomers towards regenerative repair of elastic matrix. Acta Biomater 9, 9292, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson-Saunders B., and Trapp R.G. Basic and clinical biostatistics, 2nd ed., Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson D.J., Robson P., Hew Y., and Keeley F.W. Decreased elastin synthesis in normal development and in long-term aortic organ and cell cultures is related to rapid and selective destabilization of mRNA for elastin. Circ Res 77, 1107, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMahon M.P., Faris B., Wolfe B.L., Brown K.E., Pratt C.A., Toselli P., and Franzblau C. Aging effects on the elastin composition in the extracellular matrix of cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 21, 674, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treharne G.D., Boyle J.R., Goodall S., Loftus I.M., Bell P.R.F., and Thompson M.M. Marimastat inhibits elastin degradation and matrix metalloproteinase 2 activity in a model of aneurysm disease. Br J Surg 86, 1053, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai T., Kofidis T., Bulte J.W., de Bruin J., Venook R.D., Berry G.J., McConnell M.V., Quertermous T., Robbins R.C., and Yang P.C. Dual in vivo magnetic resonance evaluation of magnetically labeled mouse embryonic stem cells and cardiac function at 1.5 t. Magn Reson Med 55, 203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman R., Uchida N., Bliss T.M., He D., Christopherson K.K., Stellwagen D., Capela A., Greve J., Malenka R.C., Moseley M.E., Palmer T.D., and Steinberg G.K. Long-term monitoring of transplanted human neural stem cells in developmental and pathological contexts with MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 10211, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissleder R., Nahrendorf M., and Pittet M.J. Imaging macrophages with nanoparticles. Nat Mater 13, 125, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam S.R., Shah A.S., Richards J., Lang N.N., Barnes G., Joshi N., MacGillivray T., McKillop G., Mirsadraee S., Payne J., Fox K.A., Henriksen P., Newby D.E., and Semple S.I. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide in patients with acute myocardial infarction: early clinical experience. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 5, 559, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevtsov M.A., Nikolaev B.P., Yakovleva L.Y., Marchenko Y.Y., Dobrodumov A.V., Mikhrina A.L., Martynova M.G., Bystrova O.A., Yakovenko I.V., and Ischenko A.M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated with epidermal growth factor (SPION-EGF) for targeting brain tumors. Int J Nanomed 9, 273, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovric J., Bazzi H.S., Cuie Y., Fortin G.R., Winnik F.M., and Maysinger D. Differences in subcellular distribution and toxicity of green and red emitting CdTe quantum dots. J Mol Med (Berl) 83, 377, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo X., Feng M., Pan S., Wen Y., Zhang W., and Wu C. Charge shielding effects on gene delivery of polyethylenimine/DNA complexes: PEGylation and phospholipid coating. J Mater Sci Mater Med 23, 1685, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiele C., Auerbach D., Jung G., Qiong L., Schneider M., and Wenz G. Nanoparticles of anionic starch and cationic cyclodextrin derivatives for the targeted delivery of drugs. Polym Chem 2, 209, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kievit F.M., and Zhang M. Surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. Acc Chem Res 44, 853, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pisanic T.R., 2nd, Blackwell J.D., Shubayev V.I., Finones R.R., and Jin S. Nanotoxicity of iron oxide nanoparticle internalization in growing neurons. Biomaterials 28, 2572, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuroo M., Nagai R., Tsuchimochi H., Katoh H., Yazaki Y., Ohkubo A., and Takaku F. Developmentally regulated expression of vascular smooth-muscle myosin heavy-chain isoforms. J Biol Chem 264, 18272, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rensen S.S.M., Thijssen V., De Vries C.J., Doevendans P.A., Detera-Wadleigh S.D., and Van Eys G. Expression of the smoothelin gene is mediated by alternative promoters. Cardiovasc Res 55, 850, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hultgardh-Nilsson A., Krondahl U., Querol-Ferrer V., and Ringertz N.R. Differences in growth factor response in smooth muscle cells isolated from adult and neonatal rat arteries. Differentiation 47, 99, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kagan H.M., and Li W. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem 88, 660, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagenseil J.E., and Mecham R.P. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev 89, 957, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.