Abstract

Background:

Head injuries have been associated with subsequent suicide among military personnel, but outcomes after a concussion in the community are uncertain. We assessed the long-term risk of suicide after concussions occurring on weekends or weekdays in the community.

Methods:

We performed a longitudinal cohort analysis of adults with diagnosis of a concussion in Ontario, Canada, from Apr. 1, 1992, to Mar. 31, 2012 (a 20-yr period), excluding severe cases that resulted in hospital admission. The primary outcome was the long-term risk of suicide after a weekend or weekday concussion.

Results:

We identified 235 110 patients with a concussion. Their mean age was 41 years, 52% were men, and most (86%) lived in an urban location. A total of 667 subsequent suicides occurred over a median follow-up of 9.3 years, equivalent to 31 deaths per 100 000 patients annually or 3 times the population norm. Weekend concussions were associated with a one-third further increased risk of suicide compared with weekday concussions (relative risk 1.36, 95% confidence interval 1.14–1.64). The increased risk applied regardless of patients’ demographic characteristics, was independent of past psychiatric conditions, became accentuated with time and exceeded the risk among military personnel. Half of these patients had visited a physician in the last week of life.

Interpretation:

Adults with a diagnosis of concussion had an increased long-term risk of suicide, particularly after concussions on weekends. Greater attention to the long-term care of patients after a concussion in the community might save lives because deaths from suicide can be prevented.

Suicide is a leading cause of death in both military and community settings.1 During 2010, 3951 suicide deaths occurred in Canada2 and 38 364 in the United States.3 The frequency of attempted suicide is about 25 times higher, and the financial costs in the US equate to about US$40 billion annually.4 The losses from suicide in Canada are comparable to those in other countries when adjusted for population size.5 Suicide deaths can be devastating to surviving family and friends.6 Suicide in the community is almost always related to a psychiatric illness (e.g., depression, substance abuse), whereas suicide in the military is sometimes linked to a concussion from combat injury.7–10

Concussion is the most common brain injury in young adults and is defined as a transient disturbance of mental function caused by acute trauma.11 About 4 million concussion cases occur in the US each year, equivalent to a rate of about 1 per 1000 adults annually;12 direct Canadian data are not available. The majority lead to self-limited symptoms, and only a small proportion have a protracted course.13 However, the frequency of depression after concussion can be high,14,15 and traumatic brain injury in the military has been associated with subsequent suicide.8,16 Severe head trauma resulting in admission to hospital has also been associated with an increased risk of suicide, whereas mild concussion in ambulatory adults is an uncertain risk factor.17–20

The aim of this study was to determine whether concussion was associated with an increased long-term risk of suicide and, if so, whether the day of the concussion (weekend v. weekday) could be used to identify patients at further increased risk. The severity and mechanism of injury may differ by day of the week because recreational injuries are more common on weekends and occupational injuries are more common on weekdays.21–27 The risk of a second concussion, use of protective safeguards, propensity to seek care, subsequent oversight, sense of responsibility and other nuances may also differ for concussions acquired from weekend recreation rather than weekday work.28–31 Medical care on weekends may also be limited because of shortfalls in staffing.32

Methods

Patient selection

We conducted a longitudinal cohort analysis of adults with a diagnosis of a concussion in Ontario, Canada, from Apr. 1, 1992, to Mar. 31, 2012 (20 yr), based on vital statistics data available through the Office of the Registrar General database.33 Ontario is Canada’s most populous province, with 12 259 564 individuals in 2003 (study midpoint).34 During the study period, the annual suicide rate in Ontario was about 9 per 100 000,35 somewhat lower than the global suicide rate of 11 per 100 00036 and the rate among former military personnel of 14 per 100 000.37,38 During the study period, Ontario health insurance covered primary, emergency and hospital care with no out-of-pocket costs to patients.39,40 The project was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre; the approval included a waiver of the need for informed consent.

We identified patients with a diagnosis of a concussion by screening physician claims data using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) diagnostic criteria for concussion (code 850) from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database.41,42 This code has been validated with high specificity (99%) and midrange sensitivity (22%–76%).43–45 Patients who were admitted to hospital immediately or within 2 days of injury were excluded because such cases tend to reflect severe brain injury (a known risk factor for suicide) and do not represent ambulatory patients with concussion.46,47 Patients under 17 years of age were excluded because most suicide deaths occur in adults.48,49 Otherwise, the selection criteria were fully comprehensive and included all patients seeking care whose diagnosis was made by a physician.

Data collection

We distinguished each case as a weekend concussion (midnight Friday to midnight Sunday) or a weekday concussion (remaining 5 days and nights of the week).50 Differentiating a weekend from a weekday concussion was based on the date of medical care, which closely corresponds to the date of injury.51,52 For patients with multiple concussions, we used the date of the first concussion, such that each person was counted once in the analyses; repeat concussions were tracked for separate secondary analyses. Further data on duration of amnesia, loss of consciousness, mechanism of injury, severity of symptoms, delays in seeking care and standardized concussion assessment scores were not available.53 Similarly, information was not available on cases that did not lead to medical attention or on whether day of the week was an imperfect proxy for concussion circumstances.

The official demographic registry provided data on patient age, sex and home location (urban or rural).34 Socioeconomic status was based on neighbourhood income quintile and was determined through the validated Statistics Canada algorithm.54–56 The health care services databases provided data on hospital admissions, outpatient contacts and diagnoses in the previous year.57,58 Prior psychiatric conditions (schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, suicide attempt, anxiety, substance abuse) were determined from physician diagnostic data for the full year before injury.59 The available databases contained no information on social stress, life events, employment status, race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, immigration status, borderline personality disorder, childhood abuse, eating disorders, suicidal ideation, novel biomarkers or other suicide risks.60–62

Outcome identification

We determined the cause of death from official death certificates encompassing definite or probable suicide, as investigated by the responsible coroner. All coroners were licensed physicians in Ontario, and suicidal death investigations have an interrater agreement of about 70% in this setting.63 We identified definite cases of suicide by ICD-9 codes (E950–E959) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10)64 codes (X60–X84) and probable cases of suicide by ICD-9 codes (E980–E987, E989) or ICD-10 codes (Y10–Y32, Y34), as validated in past research.65 The database for death certificates has been validated previously and is the official source for vital statistics reporting, as well as the authoritative file for population-based analyses of suicides.59,66,67

For each case, we recorded the forensic certainty and mechanism of suicide from the death certificate. We calculated age at death and elapsed time from index concussion from the same source, coded to the exact day. Similarly, we recorded the time since the last visit with a physician by linking to the physician care database. We also recorded the reason for the last visit, classified as a psychiatric, neurologic, medical or miscellaneous diagnosis along with the physician’s specialty.68 The available databases did not have information on pathology reports, toxicology reports, psychological scores, presence of a suicide note, litigation involvement, seniority of the investigating coroner or findings from a psychiatric autopsy.69

Statistical analysis

In the prespecified primary analysis, we assessed cumulative incidence rates (accounting for censoring and deaths) to estimate the probability of suicide after concussions on weekends and weekdays (Appendix 1, sections 1–5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150790/-/DC1). Absolute risks were calculated as deaths per 100 000 persons annually and were also compared with the prevailing suicide rate in the population during the same period.70 Cause-specific proportional hazards regression was applied to further quantify differences in suicide risk between the 2 groups before and after adjustment for baseline differences in demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses and history of suicide attempts. All reported p values were 2-tailed and were calculated with exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We developed additional statistical models with time-dependent covariables to evaluate patients who had multiple concussions over time (Appendix 1, section 7). For this approach, we applied an accumulating step function so that each concussion was considered a new event and the observed dose–response gradient correlated a patient’s total number of concussions with his or her overall risk of suicide. A 4-week interval was required to identify a subsequent diagnosis as a new concussion (an interval that was defined a priori, because symptoms typically resolve within 1 week and a variable period of rest is recommended afterward).71 We used the same step function to distinguish each additional concussion according to weekend or weekday occurrence.

Results

A total of 235 110 patients had a diagnosis of a concussion during the 20-year study period. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. About half of the patients were men, the mean age was 41 years, and most were living in an urban location. Most of the patients had no formal medical imaging, additional diagnosed fracture, prior psychiatric diagnosis, prior hospital admission or prior suicide attempt. The baseline frequency of depression and other measured characteristics was not clinically significantly different between those injured on weekends and those injured on weekdays. Anxiety disorder, the single most common prior psychiatric diagnosis, was slightly less frequent among patients injured on weekends. The distribution of characteristics of both groups was generally stable over time.

Table 1:

Characteristics of patients with diagnosis of concussion in Ontario, Canada

| Characteristic | Timing of concussion; no. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Weekend n = 39 940 |

Weekday n = 195 170 |

|

| Age, yr | ||

| ≤29 | 16 088 (40) | 67 793 (35) |

| 30–44 | 9 493 (24) | 50 390 (26) |

| 45–59 | 6 051 (15) | 35 727 (18) |

| ≥60 | 8 308 (21) | 41 260 (21) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 380 (56) | 98 922 (51) |

| Female | 17 560 (44) | 96 248 (49) |

| Income quintile | ||

| Highest | 7 141 (18) | 37 700 (19) |

| Next to highest | 7 500 (19) | 38 148 (20) |

| Middle | 7 799 (20) | 38 209 (20) |

| Next to lowest | 8 266 (21) | 38 973 (20) |

| Lowest* | 9 234 (23) | 42 140 (22) |

| Home location | ||

| Urban | 34 038 (85) | 167 975 (86) |

| Rural* | 5 902 (15) | 27 195 (14) |

| Date of enrolment† | ||

| Remote | 18 874 (47) | 87 386 (45) |

| Recent | 21 066 (53) | 107 784 (55) |

| Initial imaging | ||

| Skull radiography | 2 728 (7) | 10 678 (5) |

| Computed tomography | 7 364 (18) | 22 269 (11) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 189 (< 1) | 1 654 (1) |

| Any fracture‡ | 830 (2) | 2 234 (1) |

| Prior diagnosis§ | ||

| Schizophrenia | 336 (1) | 1 362 (1) |

| Depression | 1 707 (4) | 8 515 (4) |

| Bipolar disorder | 603 (2) | 2 720 (1) |

| Substance abuse | 1 554 (4) | 6 646 (3) |

| Anxiety disorder | 8 223 (21) | 44 003 (23) |

| Any condition¶ | 9 734 (24) | 51 181 (26) |

| Prior hospital admission§ | 1 491 (4) | 8 157 (4) |

| Prior suicide attempt§ | 56 (< 1) | 200 (< 1) |

Includes missing values.

”Remote” denotes years 1992–2001; “recent” denotes years 2002–2012.

Any bone (codes 800–829, International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision41).

Assessed during the year before concussion.

Any of the specified psychiatric diagnoses listed above.

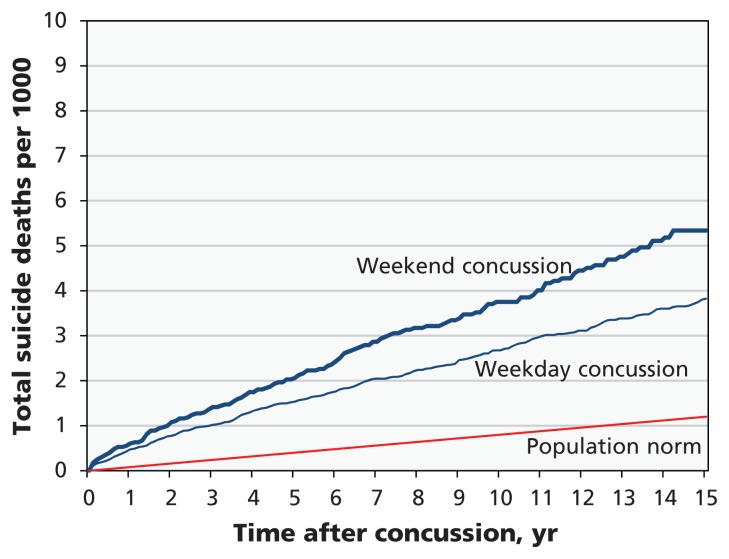

A total of 667 suicide deaths occurred over a median follow-up of 9.3 years, equivalent to 31 deaths per 100 000 patients annually. Those with a concussion occurring on weekdays accounted for 519 suicides, 1 804 520 patient-years of follow-up and an absolute suicide risk of 29 per 100 000 annually or 3 times the population norm. Those with a concussion occurring on weekends accounted for 148 suicides, 377 115 patient-years of follow-up and an absolute suicide risk of 39 per 100 000 annually or 4 times the population norm. The difference between the 2 groups was equivalent to a one-third increase in suicide risk after a weekend concussion relative to a weekday concussion. Time profiles indicated that the increased suicide risk was distributed evenly over years, with accumulating long-term differences (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Long-term risk of suicide, shown as the cumulative incidence of suicide after concussion (p < 0.001). This p value is based on the log-rank test comparing the weekend concussion group with the weekday concussion group; p values comparing study patients with the population norm were more extreme and are not reported. The main findings showed progressive differences in suicide risk after the initial concussion.

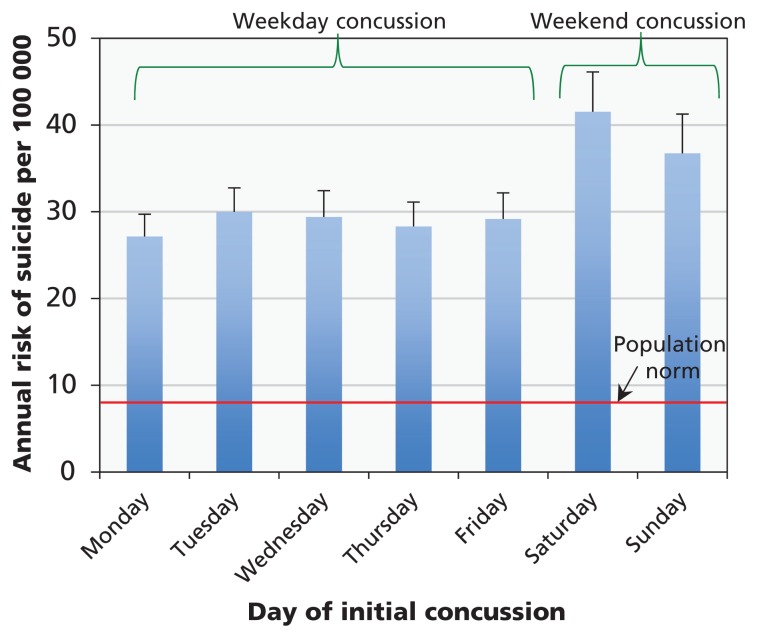

The increased risk of suicide after concussions on weekends was evident in comparisons with each individual day of the week (Figure 2). Similarly, all patient subgroups showed an absolute suicide risk above the population norm, all had a further increase in risk after concussions on weekends relative to weekdays, and the findings persisted during both remote and recent eras (Appendix 1, section 6). Patients with a prior suicide attempt had the highest absolute risk and also a further increase after a weekend concussion. Patients with no prior suicide attempt, psychiatric diagnosis or hospital admission (n = 168 188) had an absolute risk more than twice the population norm and also a further increase after a weekend concussion.

Figure 2:

Risk of suicide by day of initial concussion. Error bars denote the upper standard error of the estimates. Horizontal red line shows the population norm of 9 per 100 000. The main findings showed a consistent increase in the long-term risk of suicide after concussion on a weekday, with a further increase after concussion on a weekend.

Several other baseline factors were additional independent predictors of the long-term risk of suicide. As expected, suicide risk was associated with male sex, low socioeconomic status and prior psychiatric diagnosis (Table 2). A prior suicide attempt was the single most powerful predictor. Also as expected, a prior diagnosis of substance abuse was another powerful predictor, whereas a diagnosed fracture was not a significant predictor of suicide risk. Each specific psychiatric condition was associated with an increased risk, and no significant anomalies were apparent in analyses that explored post hoc pairwise product interaction terms. Adjustment for all predictors yielded a one-quarter increase in risk of suicide after a weekend concussion (relative risk 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.53).

Table 2:

Long-term predictors of suicide after concussion*

| Predictor | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis† | Multivariable analysis‡ | |

| Weekend concussion | 1.36 (1.14–1.64) | 1.27 (1.06–1.53) |

| Age, per yr older | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | NA |

| Sex, male | 2.28 (1.92–2.70) | 2.47 (2.08–2.94) |

| Income, low | 1.68 (1.33–2.13) | 1.30 (1.02–1.65) |

| Home, rural | 0.97 (0.78–1.20) | NA |

| Enrolment, recent§ | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) |

| Imaging¶ | 1.38 (1.15–1.66) | 1.31 (1.09–1.57) |

| Fracture | 1.09 (0.59–2.04) | NA |

| Schizophrenia | 10.78 (7.89–14.73) | 2.38 (1.68–3.37) |

| Depression | 4.32 (3.49–5.35) | 1.65 (1.30–2.11) |

| Bipolar disorder | 7.03 (5.31–9.32) | 1.96 (1.43–2.68) |

| Substance abuse | 8.43 (7.04–10.10) | 3.60 (2.94–4.41) |

| Anxiety disorder | 3.98 (3.42–4.64) | 3.04 (2.57–3.60) |

| Prior hospital admission | 2.28 (1.53–3.40) | 1.40 (0.89–2.21) |

| Prior suicide attempt | 38.83 (23.94–62.99) | 5.65 (3.26–9.81) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NA = not applicable, RR = relative risk.

Results from proportional hazards analysis, with weekdays defined as referrant.

Basic comparison with no adjustments for other baseline differences.

Adjusted comparison accounting for other baseline differences in demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses and history of suicide attempts.

“Recent” denotes years 2002–2012 (years 1992–2001 denoted as “remote”).

Includes skull radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.

The observed association between concussion and risk of suicide was accentuated in time-dependent statistical models accounting for additional concussions. A total of 24 746 patients had 2 or more concussions and accounted for 205 575 patient-years of follow-up, with 76 suicide deaths. The median interval between consecutive concussions was 214 (interquartile range 69–1018) days. Overall, each additional concussion was associated with a further increase in suicide risk (estimate 1.30, 95% CI 1.12–1.50). Analyzing all concussions in all patients yielded a one-third increase in suicide risk after a concussion on a weekend compared with weekdays (estimate 1.35, 95% CI 1.12–1.63).

We found no significant differences in suicide characteristics after a concussion on a weekend compared with a weekday. The mean time from concussion to suicide was 5.7 years (Table 3). In accordance with legal criteria, three-quarters of the cases were determined as definite suicide and the remainder as probable suicide. Poisoning was the most common mechanism, accounting for almost half of the cases in both groups. Asphyxiation was the second most common mechanism, accounting for about a third of the cases in both groups. Most of the patients had visited a physician in the month before death, primary care physicians accounted for the majority of these visits, and a psychiatric disorder was the responsible diagnosis for a minority of the visits.

Table 3:

Distinguishing circumstances of suicide

| Variable | Timing of concussion; no. (%) of suicide deaths* | |

|---|---|---|

| Weekend n = 148 |

Weekday n = 519 |

|

| Determination of death as definite suicide | 107 (72) | 393 (76) |

| Time since concussion, yr, mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 4.5 | 5.8 ± 4.8 |

| Age at death, yr, mean ± SD | 43.6 ± 14.1 | 44.1 ± 14.1 |

| Mechanism of death | ||

| Poisoning | 66 (45) | 227 (44) |

| Asphyxiation† | 51 (34) | 158 (30) |

| Violence‡ | 18 (12) | 80 (15) |

| Jumping | 8 (5) | 39 (8) |

| Other | 5 (3) | 15 (3) |

| Recent physician visit | ||

| < 1 wk | 75 (51) | 240 (46) |

| < 1 mo | 114 (77) | 370 (71) |

| < 1 yr | 142 (96) | 494 (95) |

| Physician specialty | ||

| Psychiatry | 12 (8) | 55 (11) |

| Neurology§ | 7 (5) | 16 (3) |

| Internal medicine | 16 (11) | 38 (7) |

| Family medicine | 90 (61) | 334 (64) |

| Other¶ | 17 (11) | 51 (10) |

| Recent diagnosis | ||

| Psychiatric** | 40 (27) | 166 (32) |

| Neurologic†† | 4 (3) | 25 (5) |

| Medical‡‡ | 40 (27) | 139 (27) |

| Miscellaneous§§ | 64 (43) | 189 (36) |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Unless indicated otherwise.

Asphyxiation includes hanging, strangulation, drowning and suffocation.

Violence includes firearms, explosives, crashes and stabbings.

Includes neurosurgery, anesthesiology, ophthalmology and otolaryngology.

Includes surgery, obstetrics, gynecology and medical imaging.

Codes 295 to 316 (International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision41 [ICD-9]).

ICD-9 codes 290 to 389, except psychiatric.

ICD-9 codes 001 to 779, except psychiatric or neurologic.

ICD-9 codes 780 to 999 or missing.

Interpretation

We studied data for about a quarter million adults to assess the risk of suicide after a concussion. We found that the long-term risk of suicide among those with a concussion was 3 times the population norm and was even higher if the concussion occurred on a weekend. The increased risk applied regardless of demographic characteristics, was independent of past psychiatric conditions, became accentuated with time, followed a dose–response gradient and was not as high as the risk associated with past suicide attempts. About half of the patients had visited a physician in the last week of life, typically for a diagnosis unrelated to mental illness. The absolute risk was equal to about 470 suicide deaths that might not have occurred if the prevailing risks had matched the population norm (Appendix 1, section 9).

Our findings are congruent with the results of past studies indicating that suicide attempts are the single most important long-term predictor of subsequent risk of suicide.72,73 Additional long-term predictors confirmed in this analysis included male sex, low socioeconomic status and prior psychiatric history.74,75 Past studies have cautioned that individual risk factors have low accuracy for predicting individual events.76,77 No past study, to our knowledge, has focused on concussions and tested the potential difference between weekends and weekdays. Moreover, the increased long-term risk of suicide observed in this study persisted among those who had no psychiatric risk factors and was distinctly larger than among patients after an ankle sprain (Appendix 1, section 8).

Our findings also support past research on differing theories of suicide.78–80 Past studies have suggested that a concussion can cause lasting deficits through changes in physiology (e.g., disrupted serotonin pathways), mood (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder) or behaviour (e.g., disinhibition with impulsivity).81–84 Cognitive dissonance could also lead patients and clinicians to attribute injuries after weekend recreation to misadventure, whereas injuries following weekday occupation might be attributed to the employer.85–87 With hindsight, a difference in activity restriction or cognitive dissonance might arise if the injury event was self-initiated.88,89 Further research is needed to address these issues; in the interim, our findings suggest that a history of concussion may be relevant when assessing a patient’s suicide risk.

Limitations

An alternative interpretation of our findings is unmeasured confounding. A concussion might indicate a latent predisposition toward suicide before the injury or worsening neurodegenerative deficits that precipitated the injury.90,91 Exploring these mechanisms is difficult because of the fallibility of gauging comorbid illness, concussion severity, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, long-term risk of suicide and the exact time of a concussion.92 Such mechanisms might fully explain our findings, including the observed increased risk that expanded for years after injury, did not change the mechanism of suicide and occurred despite medical care (Appendix 1, section 10). Regardless of interpretation, these findings suggest that an association between concussion and suicide is not confined to the military.

Our study also highlights the modest ability of any one factor to predict suicide because most patients do not die from suicide (Appendix 1, section 11). Furthermore, studies of suicide are prone to detection bias because social stigma leads analyses to underestimate total counts.93,94 Each case is different, such that mathematical models are fallible through a lack of myriad relevant data, such as alcohol consumption and suicidal ideation.95 Long-term predictions and generalizability are also problematic because of the network of intervening factors and shifting definitions of concussion.47,96,97 Some patients with concussion receive care that may mitigate the risk of suicide, such as antidepressant medication;98,99 however, our study lacked data on such care, which remains a topic for future research.

Conclusion

Concussion differs in 3 important ways from other risk factors for suicide. First, concussions are sometimes preventable through adequate training, the minimizing of distractions, avoidance of alcohol, use of protective gear and other safety basics.100 Second, concussions are easily neglected under a popular belief that the neurologic symptoms have an obvious cause, will resolve quickly, leave nothing visible on medical imaging and do not require follow-up.101,102 Third, concussions are rarely deemed relevant for consideration by psychiatrists or other physicians when eliciting a patient’s history.103,104 Greater attention to the long-term implications of a concussion in community settings might save lives because deaths from suicide can be prevented.105,106

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following individuals for helpful comments: Alun Ackery, Joanne Banfield, Maya Bar-Hillel, Junaid Bhatti, Mark Clemons, Allan Detsky, Richard Fralick, Richard Glazier, David Kaye, Paul Kurdyak, Anthony Levitt, Andrew Lustig, Sharon May (now Sharon Reece), Ophyr Mourad, Faisal Naqib, Matt Schlenker, Miriam Shuchman, Mark Sinyor, John Staples, Charles Tator and Jason Woodfine.

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/150790-res

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Michael Fralick and Donald Redelmeier contributed to this article in concept, design and interpretation. Deva Thiruchelvam contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. Homer Tien contributed to the concept and interpretation. Donald Redelmeier drafted the first version of the manuscript, with contributions from Michael Fralick. All of the authors participated in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Funding: This project was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences, the Major Frederick Banting Chair in Military Trauma Research, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Forces Surgeon General’s Health Research Program and the BrightFocus Foundation. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Ramchand R, Acosta J, Burns R, et al. The war within: preventing suicide in the US military. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suicides and suicide rate, by sex and by age group. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2014. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/hlth66a-eng.htm (accessed 2015 July 5). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haegerich TM, Dahlberg LL, Simon TR, et al. Prevention of injury and violence in the USA. Lancet 2014;384:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. Available: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html (accessed 2014 Oct. 30). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Links PS. The role of physicians in advocating for a national strategy for suicide prevention. CMAJ 2011;183:1987–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson A, Marshall A. The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved family and friends. Death Stud 2010; 34:625–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in US soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner LA, Ignacio R, Blow FC. Suicide and traumatic brain injury among individuals seeking Veterans Health Administration services. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2011;26:257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryan CJ, Clemans TA. Repetitive traumatic brain injury, psychological symptoms, and suicide risk in a clinical sample of deployed military personnel. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:686–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peskind ER, Brody D, Cernak I, et al. Military- and sports-related mild traumatic brain injury: clinical presentation, management, and long-term consequences. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bazarian JJ, Mcclung J, Shah MN, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in the United States, 1998–2000. Brain Inj 2005;19:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazarian JJ, Wong T, Harris M, et al. Epidemiology and predictors of post-concussive syndrome after minor head injury in an emergency population. Brain Inj 1999;13:173–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fann JR, Hart T, Schomer KG. Treatment for depression after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26:2383–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Harding HP, et al. Nine-year risk of depression diagnosis increases with increasing self-reported concussions in retired professional football players. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teasdale TW, Engberg AW. Suicide after traumatic brain injury: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:436–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver JM, McAllister TW, Arciniegas DB. Depression and cognitive complaints following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahraini NH, Simpson GK, Brenner LA, et al. Suicidal ideation and behaviours after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Brain Impair 2013;14:92–112. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazel S, Wolf A, Pillas D, et al. Suicide, fatal injuries, and other causes of premature mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury: a 41-year Swedish population study. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:326–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivens UI, Lassen JH, Kaltoft BS, et al. Injuries among domestic waste collectors. Am J Ind Med 1998;33:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lombardi DA, Sorock GS, Hauser R, et al. Temporal factors and the prevalence of transient exposures at the time of an occupational traumatic hand injury. J Occup Environ Med 2003; 45:832–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colantonio A, McVittie D, Lewko J, et al. Traumatic brain injuries in the construction industry. Brain Inj 2009;23:873–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colantonio A, Comper P. Post-injury symptoms after work related traumatic brain injury in Canadian population. Work 2012; 43:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimble S, Kendall IG, Allen MJ. An audit of care received by patients injured during sporting activities. Arch Emerg Med 1993;10:203–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psoinos CM, Emhoff TA, Sweeney WB, et al. The dangers of being a “weekend warrior”: a new call for injury prevention efforts. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:469–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts DJ, Ouellet JF, McBeth PB, et al. The “weekend warrior”: Fact or fiction for major trauma? Can J Surg 2014; 57: E62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Palo Alto (CA): Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dwiggins GA. Can I go to jail? A review of criminal liability for workplace injury or death. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 2002; 17:237–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross L, Nisbett RE. The person and the situation: perspectives of social psychology. London: Pinter & Martin; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freijy T, Kothe EJ. Dissonance-based interventions for health behaviour change: a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol 2013; 18:310–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redelmeier DA, Bell CM. Weekend worriers. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1164–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ardal S. Health analyst’s toolkit. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iron K, Zagorski BM, Sykora K, et al. Living and dying in Ontario: an opportunity for improved health information [ICES investigative report]. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health trends, Ontario. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2014. Cat. no. 82-213-XWE. Available: www12.statcan.gc.ca/health-sante/82-213/Op1.cfm?Lang=ENG&TABID=0&PROFILE_ID=0&PRCODE=35&IND=ASR&SX=TOTAL&change=no (accessed 2014 Oct. 29). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: age-standardized suicide rates (per 100 000 population). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available: www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates/en/ (accessed 2014 Dec. 23). [Google Scholar]

- 37.LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel [published erratum in JAMA 2013;310:1076]. JAMA 2013; 310:496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogaert L, Whitehead J, Wiens M, et al. Suicide in the Canadian Forces 1995 to 2012. Ottawa: Minister of National Defence; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Improving health care data in Ontario [ICES investigative report]. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alter DA, Stukel T, Chong A, et al. Lesson from Canada’s universal care: socially disadvantaged patients use more health services, still have poorer health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.International classification of diseases, 9th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macpherson A, Schull M, Manuel D, et al. Injuries in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shore AD, McCarthy ML, Serpi T, et al. Validity of administrative data for characterizing traumatic brain injury-related hospitalizations. Brain Inj 2005;19:613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bazarian JJ, Veazie P, Mookerjee S, et al. Accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury case ascertainment using ICD-9 codes. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll CP, Cochran JA, Guse CE, et al. Are we underestimating the burden of traumatic brain injury? Surveillance of severe traumatic brain injury using Centers for Disease Control International Classification of Disease, ninth revision, clinical modification, traumatic brain injury codes. Neurosurgery 2012;71:1064–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrish J, Carey S. Concussions in Canada. In: Canada injury compass. Issue no. 1 Toronto: Parachute; 2013. Available: www.parachutecanada.org/downloads/research/reports/ConcussionsInCanada.pdf (accessed 2016 Jan. 28). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kristman VL, Borg J, Godbolt AK, et al. Methodological issues and research recommendations for prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95 (Suppl 3):S265–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mustard CA, Bielecky A, Etches J, et al. Suicide mortality by occupation in Canada, 1991–2001. Can J Psychiatry 2010; 55:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skinner R, McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980–2008. CMAJ 2012;184:1029–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 2001;345:663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cunningham J, Brison RJ, Pickett W. Concussive symptoms in emergency department patients diagnosed with minor head injury. J Emerg Med 2011;40:262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisenberg MA, Andrea J, Meehan W, et al. Time interval between concussions and symptom duration. Pediatrics 2013; 132:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.King D, Brughelli M, Hume P, et al. Assessment, management and knowledge of sport-related concussion: systematic review. Sports Med 2014;44:449–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilkins R. Use of postal codes and addresses in the analysis of health data. Health Rep 1993;5:157–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkins R. Automated geographic coding based on the statistics Canada postal code conversion files, including postal codes to December 2003. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2004. Cat. no. 82-F0086-XDB. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glazier RH, Creatore M, Agha M, et al. Socioeconomic misclassification in Ontario’s Health Care Registry. Can J Public Health 2003;94:140–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams JI, Young W. A summary of studies on the quality of healthcare administrative databases in Canada. In: Patterns of health care in Ontario: the ICES practice atlas. 2nd ed Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study [ICES investigative report]. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ratnasingham S, Cairney J, Manson H, et al. The burden of mental illness and addiction in Ontario. Can J Psychiatry 2013; 58:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Z, Page A, Martin G, et al. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2011; 72:608–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beghi M, Rosenbaum JF, Cerri C, et al. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:1725–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oquendo MA, Sullivan GM, Sudol K, et al. Toward a biosignature for suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:1259–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parai JL, Kreiger N, Tomlinson G, et al. The validity of the certification of manner of death by Ontario coroners. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas KH, Davies N, Metcalfe C, et al. Validation of suicide and self-harm records in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:145–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, et al. Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study. BMJ 2014; 349:g6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishri ED, Sheppard A, Withrow D, et al. Cancer survival among First Nations people of Ontario, Canada (1968–2007). Int J Cancer 2015;136:639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henry DA, Schultz SE, Glazier RH, et al. Payments to Ontario physicians from Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care sources, 1992/93 to 2009/10 [ICES investigative report]. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1266–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sedgwick P. Incidence rate ratio. BMJ 2010;341:c4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burke MJ, Fralick M, Nejatbakhsh N, et al. In search of evidence-based treatment for concussion: characteristics of current clinical trials. Brain Inj 2015;29:300–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wenzel A, Berchick ER, Tenhave T, et al. Predictors of suicide relative to other deaths in patients with suicide attempts and suicide ideation: a 30-year prospective study. J Affect Disord 2011; 132:375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:205–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suokas J, Suominen K. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide — findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:133–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet 2009;373:1372–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gonda X, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis G, et al. Prediction and prevention of suicide in patients with unipolar depression and anxiety. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2007;6:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev 2010;117:575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aldridge D, Barrero SP. A comprehensive guide to suicidal behaviours: working with individuals at risk and their families. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Levin HS, McCauley SR, Josic CP, et al. Predicting depression following mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barkhoudarian G, Hovda DA, Giza CC. The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury. Clin Sports Med 2011;30:33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strain J, Didehbani N, Cullum CM, et al. Depressive symptoms and white matter dysfunction in retired NFL players with concussion history. Neurology 2013;81:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ilie G, Mann RE, Boak A, et al. Suicidality, bullying and other conduct and mental health correlates of traumatic brain injury in adolescents. PLoS One 2014;9:e94936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gosling P, Denizeau M, Oberlé D. Denial of responsibility: a new mode of dissonance reduction. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006; 90:722–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fotuhi O, Fong GT, Zanna MP, et al. Patterns of cognitive dissonance-reducing beliefs among smokers: a longitudinal analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2013;22:52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Korngold C, Farrell HM, Fozdar M. The National Football League and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: legal implications. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2013;41:430–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Taylor SE. Health psychology. The science and the field. Am Psychol 1990;45:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chambers A, Ibrahim S, Etches J, et al. Diverging trends in the incidence of occupational and nonoccupational njury in Ontario, 2004–2011. Am J Public Health 2015;105:338–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al. Factors associated with hopelessness in epileptic patients. World J Psychiatry 2014; 4:141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013; 136: 43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harrison-Felix CL, Whiteneck GG, Jha A, et al. Mortality over four decades after traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 1506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gjertsen F, Johansson LA. Changes in statistical methods affected the validity of official suicide rates. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shuchman M. Suicide report indicates shift at WHO. CMAJ 2014;186:E532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Redelmeier DA, Tversky A. Discrepancy between medical decisions for individual patients and for groups. N Engl J Med 1990; 322:1162–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Armstrong JS, editor. Principles of forecasting: a handbook for researchers and practitioners. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 97.West TA, Marion DW. Current recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of concussion in sport: a comparison of three new guidelines. J Neurotrauma 2014;31:159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, et al. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kisely S, Preston N, Xiao J, et al. Reducing all-cause mortality among patients with psychiatric disorders: a population-based study. CMAJ 2013;185:E50–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:e55–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dematteo CA, Hanna SE, Mahoney WJ, et al. My child doesn’t have a brain injury, he only has a concussion. Pediatrics 2010; 125:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tator CH. Concussions and their consequences: current diagnosis, management and prevention. CMAJ 2013;185:975–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Falluco EM, Hanson MD, Glowinski AL. Teaching pediatric residents to assess adolescent suicide risk with a standardized patient module. Pediatrics 2010;125:953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ronquillo L, Minassian A, Vilke GM, et al. Literature-based recommendations for suicide assessment in the emergency department: a review. J Emerg Med 2012;43:836–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Keshavarz H, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Streiner DL, et al. Screening for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open 2013;1:E159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.