Abstract

The recent findings that the narrow-specificity endoribonuclease RNase III and the 5′ exonuclease RNase J1 are not essential in the Gram-positive model organism, Bacillus subtilis, facilitated a global analysis of internal 5′ ends that are generated or acted upon by these enzymes. An RNA-Seq protocol known as PARE (Parallel Analysis of RNA Ends) was used to capture 5′ monophosphorylated RNA ends in ribonuclease wild-type and mutant strains. Comparison of PARE peaks in strains with RNase III present or absent showed that, in addition to its well-known role in ribosomal (rRNA) processing, many coding sequences and intergenic regions appeared to be direct targets of RNase III. These target sites were, in most cases, not associated with a known antisense RNA. The PARE analysis also revealed an accumulation of 3′-proximal peaks that correlated with the absence of RNase J1, confirming the importance of RNase J1 in degrading RNA fragments that contain the transcription terminator structure. A significant result from the PARE analysis was the discovery of an endonuclease cleavage just 2 nts downstream of the 16S rRNA 3′ end. This latter observation begins to answer, at least for B. subtilis, a long-standing question on the exonucleolytic versus endonucleolytic nature of 16S rRNA maturation.

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of bacterial gene expression occurs by transcriptional and translational control, as well as by regulating mRNA decay and processing, which modulates the amount and suitability of an mRNA available for translation. In Bacillus subtilis, mRNA processing generally occurs by a number of relatively non-specific enzymes: the endonuclease RNase Y, the 5′-to-3′ exonuclease RNase J1, several 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases and one or more RNA pyrophosphohydrolases (RppH) (1–7). Decay is initiated either by (1) RppH-mediated conversion of the 5′-terminal triphosphate to a monophosphate, giving RNase J1 access to degrade in the 5′-to-3′ direction, or (2) RNase Y internal cleavage(s), which generates a downstream fragment that is degraded by RNase J1 and an upstream fragment that is degraded by 3′ exonucleases. None of the genes encoding individual RNases or pyrophosphohydrolases are essential, including the genes for RNase J1 and RNase Y, as we have shown (8). The activities of these enzymes on specific mRNAs can be controlled by 5′-proximal RNA structure (9), 5′-terminal nucleotide sequence (10), ribosome flow (11) and RNA-binding proteins (12).

In contrast to the relatively non-specific nature of the ribonucleases mentioned above, B. subtilis RNase III, encoded by the rnc gene, is a narrow-specificity enzyme that recognizes particular double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures (13,14). Virtually all bacterial species appear to contain at least one RNase III-like protein, which is characterized by a specific endonuclease domain (the RNase III domain) and a dsRNA-binding domain. RNase III can cleave one strand or both strands of a double-stranded target (13). Long-known native targets of B. subtilis RNase III are precursor 30S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (15) and small cytoplasmic RNA (scRNA) encoded by the scr gene (16). In the case of rRNA, dsRNA stems on either side of 16S and 23S precursor rRNA are cleaved by RNase III. Further 5′-end maturation of 16S rRNA occurs by an unknown endonuclease cleavage, followed by RNase J1 exonucleolytic processing to the mature 5′ end (17). The nature of 16S rRNA 3′-end maturation has not been elucidated. B. subtilis also contains a second RNase III-like protein named Mini-III, which consists of only the RNase III catalytic domain and which catalyzes 23S rRNA maturation directly (18). We and others have also characterized non-native targets of RNase III encoded by phage SP82 (19,20).

Bacillus subtilis RNase III was thought to be essential, as the rnc gene encoding the enzyme could not readily be deleted (15). Condon et al. (3) used a tiling microarray to study the effect of a 30-fold reduction in RNase III concentration in B. subtilis, and found a significant (≥2-fold) effect on 11% of coding sequences (CDSs). Most of the changes in gene expression were due to transcriptional effects rather than direct cleavage by RNase III. The current study on the effect of B. subtilis RNase III was initiated after a more recent study showed that, in fact, RNase III is not essential in B. subtilis (21). Rather, the inability to delete rnc is due to expression of toxin genes carried on the Skin and SPβ prophages. mRNAs encoded by these genes are targeted for cleavage by RNase III when they complex with complementary non-coding RNAs. In the absence of RNase III, the toxin mRNAs accumulate, resulting in lethal levels of toxin proteins. In a strain deleted for the Skin and SPβ prophages, RNase III is no longer essential and the strain grows normally (21).

In other organisms, there are several well-known examples of gene regulation by RNase III cleavage of mRNA, including, in Escherichia coli, autoregulation of the rnc gene (22–24) and regulation of the rpsO-pnp operon (25,26). In these cases, RNase III cleavage in a leader region results in destabilization of the mRNAs. Kushner et al. used tiling microarrays to examine gene expression in an E. coli RNase III null mutant. They found significant (1.5-fold) decreased or increased expression of 12% of CDSs (27), many of which were due to indirect effects (e.g., transcriptional). These authors reported the first known instance of a CDS (nirB) directly targeted by RNase III. More recently, Schroeder et al. used a dsRNA-specific antibody to probe for dsRNAs in E. coli wild-type and rnc mutant strains, and found abundant sense/antisense pairings that were RNase III targets (28). Additional evidence of CDS cleavage by RNase III was obtained in studies of RNase III targets in Staphylococcus aureus (24) and Streptomyces coelicolor (29). These studies used immunoprecipitation of RNA fragments bound to an inactive RNase III enzyme to identify RNase III targets. Large numbers of antisense RNAs were identified as RNase III substrates in the former study (24). Pervasive processing of sense–antisense pairings by RNase III has been suggested by other experiments in S. aureus, with evidence that the same occurs in B. subtilis (30).

In the current study, we adapted to B. subtilis an RNA-Seq-based method of mapping 5′-monophosphorylated ends, first used in Arabidopsis experiments (31–33). The method was able to directly identify RNase III cleavage sites on a global scale, to discover an endonuclease cleavage that is involved in 3′ end maturation of 16S rRNA, and to demonstrate the importance of RNase J1 on 3′-terminal fragment turnover.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. For RNA isolation, cells were grown overnight in Luria Broth (LB medium) plus antibiotic at 37°C, and then diluted 1:50 for growth until mid-log phase (Klett ∼70) without antibiotic. Concentrations of antibiotics were: chloramphenicol 4 μg/ml, erythromycin 5 μg/ml, kanamycin 5 μg/ml, phleomycin 2 μg/ml, spectinomycin 200 μg/ml. For analysis of putP mRNA, strains were grown in a modified Spizizen minimal medium supplemented with proline: 1.4% K2HPO4, 0.6% KH2PO4, 0.1% Na citrate•2H2O, 1 mM MgSO4•7H20, 0.5% glucose, 60 μg/ml threonine, 60 μg/ml tryptophan, 0.01% proline.

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Designation in this study | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BG578 | W168 Pspac-rnjA ery pMAP65 kan | (65) | |

| BG875 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan | rnc+ (rnc+ sfp− in Figure 4C) | (21) ‘CCB364’ |

| BG876 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan Δrnc::spc | (21) ‘CCB422’ | |

| BG877 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan Δrnc::ery | Δrnc | (42) |

| BG879 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan Δrnc::ery ΔrnjA::spc | Δrnc ΔrnjA | (42) |

| BG880 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan ΔrnjA::spc | rnc+ ΔrnjA | (42,68) |

| BG898 | W168 Pspac-rnjA ery Δrny::spc pMAP65 kan | This study | |

| BG908 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan Δrnc::cat | This study | |

| BG917 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan rncE138A (pMAP65) | This study | |

| BG923 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan rncE138A | E138A | This study |

| BG935 | W168 sfp+Em | R. Kolter laboratory | |

| BG940 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan sfp+Em | rnc+ sfp+ in Figure 4C | This study |

| BG942 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan sfp+Em rncE138A | rnc− sfp+ in Figure 4C | This study |

| BG981 | SMY ΔputR::cat | (45) ‘BB3330’ | |

| BG983 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan ΔputR::cat | rnc+ ΔputR | This study |

| BG984 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan Δrnc::ery ΔputR::cat | Δrnc ΔputR | This study |

| BG994 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan amyE::Pspac-putP | This study | |

| BG995 | W168 ΔSkin ΔSPβ::PIID-sspB kan amyE::Pspac-putP Δrnc::ery | This study | |

| CCB434 | W168 ΔrnjA::spc | (8) | |

| CCB441 | W168 Δrny::spc | (8) | |

| CCB418 | W168 txpA-10Δ ΔyonT::ery Δrnc::spc | (3) | |

| CCB078 | W168 ΔrnjB::spc | (65) | |

| CCB501 | W168 ΔrnjB::spc ΔrnjA::kan (W168 version of CCB449) | (8) |

The strain carrying the rnc E138A mutation was made as follows: the wild-type rnc CDS carried on plasmid pBSR2 (34) was disrupted with a chloramphenicol (Cm)-resistance gene, giving plasmid pJMD2. Strain BG875, the W168 derivative with Skin and SPβ phage deletions, was transformed to Cm resistance with ScaI-linearized plasmid pJMD2 to give strain BG908. The rnc CDS carried on plasmid pJMD1, a derivative of pYH250 (35), was mutagenized with the QuikChange protocol (Agilent Technologies), to give the E138A mutation on plasmid pJMD3. (The sequences of oligonucleotides used in this study are given in Table S1.) BG908 was transformed with ApaI-linearized pJMD3 and plasmid pMAP65 (36), to select for phleomycin-resistant cells that were transformed by plasmid pMAP65 and possibly co-transformed with pJMD3. Approximately 2000 colonies were screened for loss of Cm resistance and one colony was obtained that carried the rnc E138A substitution for wild-type rnc. This strain was designated BG917. BG917 was cured of pMAP65 by growing cells without phleomycin selection in the presence of 0.006% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (37). After several passages into fresh media, strain BG923 was obtained.

The strains for the drop collapse assay were constructed by transforming BG935 chromosomal DNA into BG875 and BG923 to yield BG940 and BG942, respectively. Similarly, strains BG983 and BG984 were constructed by transforming BG875 and BG877, respectively, with BG981 chromosomal DNA. Gene knockouts were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

Growth curves

After overnight growth in 2X YT medium, duplicate samples of cells were diluted 1:20 in water and the OD600 was adjusted to 0.2. A 96-well plate was prepared with 190 μl of 2× YT medium to which 10 μl of each sample was added. Cells were grown in a BioTek PowerWave XS2 Microplate Spectrophotometer with shaking for 24 h at 37°C, with kinetic reads taken at 1 h intervals. To calculate doubling time, the kinetic readings were plotted on a semi-log graph in Microsoft Excel. The linear regression function was then used to determine the doubling time for the linear (logarithmic growth) portion of the curve, using the equation doubling time = log2/slope.

RNA isolation and Northern blotting

RNA was isolated using the hot phenol method, as described (38). RNA concentrations were measured using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and concentrations were adjusted to give equal amounts of RNA loaded per lane. Before Northern blot analyses, RNA samples were run on a MOPS gels to check RNA quality and quantity by comparing rRNA band intensities. Total RNA was separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (6% polyacrylamide/7M urea) or denaturing agarose gels (1.5% agarose/7% formaldehyde MOPS) and blotted onto positively-charged nylon membranes (Amersham HyBond N+; GE Healthcare). Hybridizations were performed in roller bottles with varying conditions depending on whether a 5′ end-labeled oligonucleotide or riboprobe was used. Band signal intensity from each lane was normalized by stripping blots and probing for 16S rRNA, using an oligonucleotide complementary to 1405–1424 nts (39).

Parallel analysis of RNA ends (PARE)

The PARE protocol described previously (32) was adapted to B. subtilis (see Supplementary Figure S1). Ribosomal RNA was removed from 5 μg of total RNA using the Ribo-Zero™ rRNA Removal Kit for Gram-Positive Bacteria (Illumina), per the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentrations in rRNA-depleted samples were determined with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen). Equal amounts of samples were used to construct the PARE libraries using the NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (Set 1). The manufacturer's protocol was modified so that 5′ monophosphorylated ends that result from endonuclease cleavage or pyrophosphohydrolase activity were preferentially selected. Briefly, after 3′ SR Adaptor ligation, reverse transcriptase (RT) primer hybridization and 5′ SR Adaptor ligation — performed as per the manufacturer's protocol — the reaction mixture volume was brought to 100 μl and samples were cleaned up with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). A total of 12 μl of RNA was recovered following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was fragmented using the NEBNext® Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module at 94°C for 4 min, and 2 μl of stop solution was added. After a second RNeasy MinElute cleanup, half of the RNA (6 μl) was again ligated to the 3′ SR Adaptor. Thus, after magnesium fragmentation only RNAs that retained their 5′ SR Adaptor (and original 5′ monophosphate) would undergo subsequent RT and PCR amplification. After addition of the RT primer, the reaction volume was adjusted to 30 μl and RT/PCR amplification reactions were performed as per the manufacturer's protocol, using barcoded primers.

One-tenth of the PCR reaction was run on a 1.5% agarose gel to visualize the library, which consisted of cDNA ranging from 50 to ∼500 nts. A total of 20 μl of the cDNA library were prepared for Illumina sequencing using a 1.5× volume of Agencourt AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The procedure was repeated twice, and the sample was eluted in a final volume of 20 μl. Samples were stored at −80°C. Prior to sequencing, each sample was checked on an Agilent BioAnalyzer. Samples that contained >125 bp cDNA were used for 50-nts single-end RNA-Seq reads on an Illumina MiSeq slide. Reads were mapped to the B. subtilis genome as described (5).

5′ RLM-RACE

Total RNA (250 ng) was used for each sample. The 5′ SR Adaptor from the NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (Set 1) was ligated to RNA at 25°C for 1 h. Primer extension was performed as described previously (40), using the SuperScript III protocol from Invitrogen. PCR amplification was performed using Taq PCR Master Mix Kit (Qiagen) and the following conditions: 94°C/3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C/30 s, 55°C/30 s, 72°C/30 s and 5 min extension at 72°C. Nested PCR was then performed on 1 μl of the primary PCR reaction as template, using the same conditions as above. Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table S1.

A total of 10 μl of the final PCR reaction was visualized on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel. The remainder of samples that displayed bands in the rnc+ strain only was run on a preparative 6% native polyacrylamide gel. The band of interest was cut out and soaked overnight at 37°C in 300 μl of RNA diffusion buffer (0.5 M ammonium acetate, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.2% SDS). The eluate was extracted with phenol:chloroform (1:1) and ethanol precipitated. The precipitate was resuspended in 10 μl of water and ligated into the PCR cloning vector, pGEM-T (Promega), for cloning and sequencing.

Drop-collapse assay

For the qualitative assay, cultures were grown overnight in 5 ml LB with erythromycin at 5 μg/ml. A total of 100 μl of the overnight culture was pelleted and 5 μl of supernatant was carefully added to 5 μl of water that was placed on the lid of a square petri dish. The drops were allowed to sit for several minutes before being photographed. The amount of spreading of the water droplet corresponded to the amount of surfactin in the culture supernatant.

For the quantitative assay, purified surfactin (Sigma #S3523) was dissolved in 1 ml 100% ethanol for a 10 mg/ml stock solution, which was diluted 1:100 in LB media to give a 100 μg/ml working solution of surfactin. Overnight cultures grown in 5 ml LB + erythromycin were pelleted and dilutions of the supernatant were prepared. The drop collapse assay was performed as above, using control surfactin dilutions (100, 50, 25, 12.5 and 6.25 μg/ml) and culture supernatant dilutions (undiluted, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, 1:32). The amount of surfactin present in each supernatant was calculated comparing the highest dilution of supernatant where drop collapse was observed to the control surfactin dilutions.

RESULTS

RNase III-generated 5′ ends

Experiments to map RNase III 5′ ends were performed in strains that were: deleted for the Skin and SPβ prophages to render rnc non-essential; deleted for the rnjA gene encoding the 5′ exonuclease RNase J1; and either rnc wild-type (rnc+) or rnc deleted (Δrnc) (see Table 1 for strains used in this study). We used strains that were deleted for rnjA in the expectation that this would better preserve 5′ ends that were generated by RNase III. Growth rates were determined for rnc+ and Δrnc strains, with or without rnjA present (Table 2). While the absence of RNase J1 caused a major slowing of the growth rate, proportionally similar to what was observed previously (8), this was not affected by the presence or absence of RNase III. Apparently, alternate pathways for rRNA processing are sufficient to allow normal growth, and the lack of processing of many other mRNAs that are RNase III targets (see below) does not result in an effect on growth rate in rich medium.

Table 2. Growth rate of rnc+ and Δrnc strains.

| Strain | Doubling time |

|---|---|

| rnc+ | 43.4 |

| Δrnc | 43.1 |

| rnc+ ΔrnjA | 145.7 |

| Δrnc ΔrnjA | 153.8 |

5′ ends generated by RNase III were mapped by the PARE method (31). Total RNA was isolated from exponential phase cultures of rnc+ and Δrnc strains grown in LB medium. After rRNA depletion, the RNA preparation was processed by the PARE protocol (Supplementary Figure S1; see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). Briefly, RNA molecules used to prepare the PARE library would have either a 5′-triphosphate end representing a transcription start site (TSS) or a 5′-monophosphate end. The latter could be generated by RppH activity at the TSS, or by endonucleolytic cleavage internally. Ligation of adapters to 5′-monophosphorylated and 3′ hydroxylated ends, followed by amplification, created a PARE library that was subject to 50-nts reads, starting at the junction of the 5′ adaptor with the 5′ end of the RNA fragment. The chromosomal location of a 5′ monophosphorylated end was identified as the first position in a ∼50-nts read. As discussed below, the PARE method does not always identify the exact 5′ end of an RNA. The term ‘PARE peak’ was used to refer to a stretch of increased reads that begins with a 5′ monophosphate end putatively generated by in vivo processing.

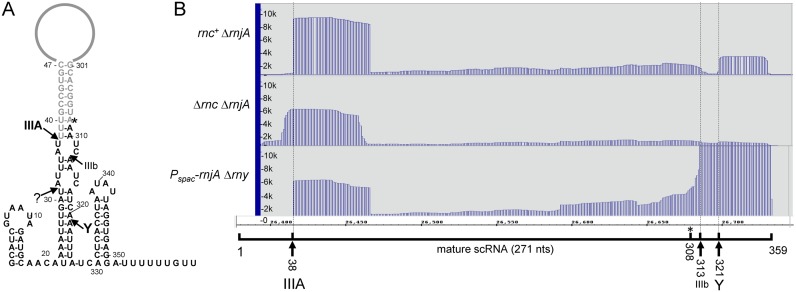

PARE protocol validation—scRNA

Previous work had identified major and minor RNase III cleavage sites in scRNA (16,41), which are indicated in Figure 1A (cleavage sites IIIA and IIIb). The mature 5′ end of scRNA is generated directly by RNase III cleavage at 38 nts, while the mature 3′ end is primarily the result of RNase Y cleavage at around 320 nts, followed by exonucleolytic trimming to 308 nts (42). In the current analysis, the PARE read data from the rnc+ strain showed a prominent 5′-proximal PARE peak beginning at scRNA 38 nts (Figure 1B, top panel), the nucleotide at which the major RNase III cleavage site had been mapped previously. (There is a minor shoulder of a few nucleotides preceding the major peak at 38 nts. This is observed frequently in the PARE data, and may reflect additional cleavages by other endonucleases in the region of a major RNase III cleavage site.) This result indicated that the PARE protocol could reliably identify RNase III cleavage sites in vivo.

Figure 1.

Analysis of scRNA. (A) Schematic diagram of scRNA, showing major sites of RNase III (IIIA) and RNase Y (Y) cleavage. Minor site of RNase III cleavage (IIIb) is also indicated. Sequences present in the fully-processed scRNA are shown in gray. The mature 5′ end is created directly by RNase III cleavage at 38 nts, and the mature 3′ end is created by RNase Y cleavage, followed by 3′ exonuclease trimming to 308 nts (asterisk). (B) PARE data for scRNA in three strains, with genotypes indicated at left. Below the PARE data is a schematic of the 359-nts scRNA transcript with endonuclease cleavage sites indicated and correlated with PARE peaks.

There was no PARE peak for the scRNA minor 3′-proximal RNase III cleavage at 313 nts (Figure 1B, top panel), which was not unexpected, as the major 3′-proximal cleavage is catalyzed by RNase Y at 321 nts (42), for which a PARE peak is observed (Figure 1B, top panel). This peak is not as prominent as that of the scRNA 5′ end, likely because the fragment generated by this peak is turned over, whereas the mature scRNA containing the 5′ end at 38 nts is stable. The RNase Y PARE peak is obscured in a strain that is deleted for RNase Y (Figure 1B, bottom panel). Instead, a strong PARE peak beginning at the secondary RNase III cleavage site is detected, as has been observed by Northern blot analysis (42).

In the Δrnc deletion strain, the 5′-proximal PARE peak was shifted upstream by 6 nts (Figure 1B, middle panel). We have previously examined this cleavage by Northern blot and primer extension analyses, and confirmed that the 5′ end is several nucleotides upstream of the mature 5′ end in the rnc+ strain (42). We suggested that this cleavage, by an unknown endonuclease, may represent a quality control mechanism to initiate degradation of scRNA that is not processed by RNase III.

Messenger RNA targets of RNase III

PARE data were analyzed for peaks that mapped to mRNA sites and that were significantly more prominent in the rnc+ strain than the Δrnc strain. To account for changes in gene expression caused indirectly by the loss of RNase III (e.g., transcriptional effects), RNA samples from the rnc+ and Δrnc strains were also subject to a standard RNA-Seq analysis (Supplementary Table S2). For CDSs that had a read coverage of at least 1.0 read per base in both strains (2414 genes), the absence of RNase III resulted in a >2-fold increase in 209 genes and a >2-fold decrease in 329 genes. This amounts to significant effects on ∼13% of the B. subtilis genome, which is similar to the effect of an RNase III depletion found previously (3), although the strains that were used in the previous study were rnjA wild-type. For PARE peaks with an average of >100 reads per position in the peak, we calculated the ratio of PARE reads in rnc+ and Δrnc strains, and divided this by the ratio of RNA-Seq reads over the same positions in rnc+ and Δrnc strains, to give a ‘ratio of ratios’ or ‘RR.’ Sites with a high RR value are those that are highly likely to be direct targets of RNase III cleavage, rather than due to indirect effects of the presence or absence of RNase III on gene expression. After normalizing PARE reads, we tallied 53 mRNAs and 5 intergenic RNAs that had one or more peaks with an RR of >10 (Table 3), a conservatively high threshold. Of the 53 mRNA targets, there was no bias toward any gene functional category (data not shown), nor was there bias to the operonic position of the CDS (Table 3). For only four of these genes were cleavage sites mapped to genomic positions that have identified antisense RNA transcripts, according to recent transcriptome mapping data (43) (Table 3).

Table 3. Genes with RR value > 10.

| Position | Peak start | Avg depth | rnc+ ΔrnjA reads | Δrnc ΔrnjA reads | Peak RR | Operon position | Antisense overlap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BSU00090,guaB | 16 250 | 112.37 | 409.31 | 126.56 | 11.3 | monocistronic | |

| 2 | BSU00400,yabE | 49 142 | 219.45 | 23.04 | 12.26 | 16.5 | monocistronic | S25 |

| 3 | 5′_BSU00490,spoVG | 55 847 | 112.38 | 157.86 | 25.73 | 11.1 | monocistronic | |

| 4 | BSU01060,ybxB | 121 313 | 142.38 | 2.17 | 3.28 | 39.5 | ||

| 5 | BSU01260,rplN | 140 709 | 134.50 | 88.14 | 197.09 | 10.1 | ||

| 6 | 5′_BSU02040,ybdN | 224 045 | 505.79 | 0.90 | 1.43 | 14.4 | ||

| 7 | BSU03220,ycgO (putP) | 348 421 | 148.67 | 8.61 | 1.24 | 63.6 | 3 | S117 |

| 8 | BSU03480,srfAA | 377 519 | 123.54 | 20.75 | 26.72 | 36.7 | 1 | |

| 9 | BSU03670,dtpT | 417 038 | 186.39 | 17.46 | 75.24 | 14.1 | monocistronic | |

| 10 | BSU03830,yclQ | 435 313 | 116.07 | 25.41 | 18.56 | 67.1 | 4 | |

| 11 | 3′_BSU07560,pel | 829 226 | 221.39 | 3.52 | 10.28 | 11.1 | monocistronic | |

| 12 | BSU09640,yhdY | 1 039 831 | 362.95 | 3.09 | 8.79 | 12.0 | ||

| 13 | BSU11590,yjbL | 1 236 790 | 114.19 | 2.67 | 2.99 | 20.0 | ||

| 14 | BSU12100,yjeA | 1 281 630 | 218.17 | 6.47 | 23.37 | 12.3 | monocistronic | |

| 15 | BSU13490,ykrL (htpX) | 1 415 027 | 384.04 | 21.01 | 46.98 | 11.1 | ||

| 16 | 5′_BSU14629,ykzW | 1 534 091 | 131.12 | 1.35 | 7.71 | 13.9 | ||

| 17 | BSU14629,ykzW<>BSU14630,speA | 1 534 171 | 1553.17 | 11.0 | ||||

| 18a | BSU15140,mraW | 1 581 006 | 325.37 | 240.06 | 27.30 | 17.3 | 2 | |

| 18b | BSU15140,mraW | 1 581 170 | 996.75 | 17.8 | ||||

| 19 | BSU15210,spoVE | 1 590 701 | 272.95 | 32.89 | 56.27 | 13.4 | 4 | |

| 20 | BSU15600,cysC<>BSU15610,sumT | 1 633 979 | 203.72 | 151.9 | 4, 5 | |||

| 21 | BSU15710,priA | 1 645 900 | 124.22 | 6.20 | 3.07 | 150.4 | ||

| 22 | BSU15910,fabG | 1 664 924 | 113.09 | 22.84 | 27.53 | 14.0 | 4 | |

| 23 | BSU16550,dxr | 1 723 065 | 459.63 | 9.55 | 14.64 | 10.8 | ||

| 24 | BSU17450,glnR | 1 878 240 | 754.45 | 21.72 | 36.29 | 17.5 | 1 | |

| 25 | BSU17460,glnA | 1 878 611 | 125.00 | 82.86 | 130.06 | 12.1 | 2 | |

| 26 | BSU18080,yneT | 1 932 721 | 148.30 | 4.03 | 14.47 | 19.0 | ||

| 27a | BSU18380,iseA | 2 002 730 | 165.90 | 27.50 | 31.30 | 81.9 | monocistronic | |

| 27b | BSU18380,iseA | 2 002 958 | 118.29 | 26.9 | ||||

| 27c | 3′_BSU18380,iseA | 2 003 024 | 462.58 | 12.6 | ||||

| 28 | BSU19650,yodM | 2 137 281 | 144.57 | 0.93 | 1.45 | 35.5 | ||

| 29 | BSU22370,aspB | 2 348 163 | 180.94 | 39.47 | 35.00 | 10.6 | ||

| 30 | BSU22840,engA | 2 391 372 | 183.00 | 7.43 | 17.65 | 14.9 | ||

| 31 | BSU23860,yqjI (gndA) | 2 481 775 | 315.90 | 95.85 | 93.23 | 13.3 | 2 | |

| 32 | BSU24620,tasA | 2 553 194 | 120.35 | 7.07 | 25.36 | 23.2 | 3 | |

| 33 | BSU24930,yqzD | 2 576 623 | 177.29 | 9.89 | 13.42 | 21.8 | 1 | |

| 34 | 5′_BSU24990,pstS | 2 580 671 | 1311.06 | 1.39 | 2.36 | 24.9 | 1 | |

| 35 | BSU25380,yqfA (floA) | 2 618 398 | 130.36 | 21.74 | 18.18 | 10.8 | 2 | |

| 36a | BSU25440,yqeU (rsmE) | 2 623 390 | 129.62 | 56.28 | 40.18 | 14.9 | 8 | |

| 36b | BSU25440,yqeU (rsmE) | 2 623 510 | 248.82 | 50.8 | ||||

| 36c | BSU25440,yqeU (rsmE) | 2 623 742 | 150.14 | 16.9 | ||||

| 37 | 5′_BSU26619,yrzO | 2 720 474 | 195.94 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 31.7 | ||

| 38 | BSU32060,yuiD | 3 298 413 | 116.50 | 9.05 | 6.48 | 12.1 | monocistronic | |

| 39 | 5′_BSU32070,yuiC | 3 298 554 | 347.87 | 1.52 | 1.31 | 10.6 | monocistronic | |

| 40 | BSU32110,yumC | 3 302 457 | 181.23 | 28.59 | 24.35 | 10.7 | monocistronic | |

| 41 | BSU32200,yutJ | 3 309 256 | 136.70 | 16.88 | 44.65 | 11.7 | monocistronic | |

| 42 | 5′_BSU33000,htrB | 3 385 425 | 369.02 | 7.84 | 12.42 | 14.8 | monocistronic | |

| 43 | BSU33950,cggR | 3 483 532 | 158.65 | 3.88 | 15.76 | 13.4 | 1 | |

| 44 | BSU34780,yvcI<>BSU34790,trxB | 3 573 049 | 2938.41 | 10.2 | ||||

| 45 | BSU35650,lytR (tagU) | 3 663 332 | 241.83 | 8.00 | 15.44 | 11.3 | monocistronic | |

| 46a | BSU36410,mbl | 3 747 544 | 169.82 | 26.15 | 45.07 | 13.0 | 3 | |

| 46b | BSU36410,mbl | 3 748 034 | 219.33 | 19.6 | ||||

| 47 | 5′_BSU36510,amtB | 3 756 769 | 129.14 | 4.92 | 19.76 | 26.8 | 1 | |

| 48 | 3′_BSU36520,glnK | 3 758 290 | 877.27 | 7.79 | 24.15 | 12.9 | 2 | |

| 49 | BSU36760,murAA | 3 778 464 | 134.98 | 59.60 | 233.24 | 10.6 | monocistronic | S1420 |

| 50 | BSU36830,atpA | 3 784 404 | 108.89 | 65.91 | 132.29 | 16.3 | 6 | |

| 51 | BSU37150,pyrG | 3 811 842 | 144.96 | 14.23 | 55.65 | 10.7 | monocistronic | |

| 52 | BSU37330,argS | 3 833 842 | 174.20 | 68.10 | 60.87 | 19.6 | monocistronic | |

| 53 | BSU37800,yweA<>BSU37810,spsL | 3 882 701 | 199.16 | 13.9 | ||||

| 54 | BSU38680,yxlD | 3 969 858 | 131.02 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 14.4 | 3 | |

| 55 | BSU39250,yxiE | 4 031 849 | 190.50 | 55.90 | 19.72 | 10.5 | 3 | |

| 56 | BSU39270,bglP<>BSU39280,yxxE | 4 031 756 | 35479.18 | 15.9 | 1 | |||

| 57 | BSU39400,pdp | 4 049 094 | 120.11 | 34.94 | 63.68 | 23.0 | 4 | |

| 58 | BSU41030,jag | 4 213 719 | 137.46 | 35.23 | 76.43 | 10.8 | 2 | S1579 |

Predicted structure of selected RNase III target sites

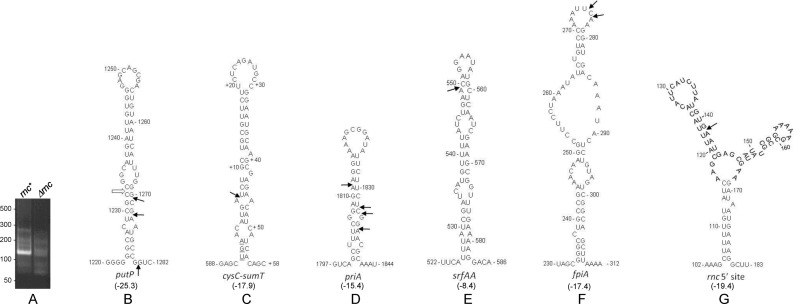

As mentioned, in many cases the start of a PARE peak was preceded by a shoulder representing a low level of 5′ ends upstream of an actual RNase III cleavage site. These may be due to cleavage by another activity (e.g., RNase Y) in a neighboring upstream region. We therefore used 5′ RNA ligation-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RLM-RACE) to map more precisely 5′ ends in mRNA regions that were predicted by PARE to be RNase III target sites. Thirteen genes were selected for 5′ RLM-RACE experiments, and six genes for which the RLM-RACE protocol gave a clear PCR product of the predicted size in the rnc+ strain and no comparable product in the Δrnc strain were analyzed (cf. Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S2). The 5′ ends mapped by RLM-RACE were, in most cases, either at the site mapped by PARE or a few nucleotides away (Table 4; see ‘Discussion’ section).

Figure 2.

5′ RLM-RACE mapping of RNase III cleavage sites. (A) 5′ RLM-RACE amplification products for mapping putP 5′ end generated by RNase III. A PCR product of the expected size is observed only in the rnc+ strain. (B–G) Predicted structures of RNA regions initially identified by PARE analysis to contain RNase III cleavage sites. The structures with the lowest predicted free energy are shown. Values in kilocalories/mol are given in parentheses below each structure. 5′ ends mapped by RLM-RACE are indicated by arrows. Open arrow in Figure 2B indicates the 5′ end of a fragment observed by PARE and Northern blot data but not mapped by RLM-RACE (see text).

Table 4. 5′-RACE mapping of RNase III cleavage sites.

| Gene | CDS | PARE peak (approximately) | 5′-RACE colonies | Genome location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| putP | 347 150→348 571 | 348 421 | 1 of 4 | 348 420 |

| 2 of 4 | 348 422 | |||

| 1 of 4 | 348 429 | |||

| cysC-sumT | 1 633 369→1 633 962 | 1 633 979 | 4 of 4 | 1 633 969 |

| 1 634 061→1 634 834 | ||||

| fpiA (yclQ) | 435 036→435 989 | 435 313 | 1 of 4 | 435 310 |

| 3 of 4 | 435 311 | |||

| priA | 1 644 068→1 646 485 | 1 645 900 | 4 of 11 | 1 645 878 |

| 2 of 11 | 1 645 900 | |||

| 1 of 11 | 1 645 901 | |||

| 4 of 11 | 1 645 903 | |||

| srfAA | 376 968→387 731 | 377 519 | 5 of 5 | 377 518 |

| rnc | 1 665 710→1 666 459 | 1 665 851 | 6 of 6 | 1 665 851 |

The predicted secondary structures surrounding confirmed RNase III cleavage sites, according to mfold (44), are shown in Figure 2. Several of these—putP, intergenic cysC-sumT, priA (Figure 2B–D)—show classic RNase III target sites with cleavage on one or both sides of a relatively stable, stem-loop structure with small internal bulges (13,14). For putP, 5′ RLM-RACE mapping gave only cleavages on the downstream side, but the PARE data and follow-up Northern blot analysis (see below) indicated an additional cleavage on the upstream side of the stem-loop, as shown by the open arrow in Figure 2B. Cleavage of srfAA mRNA occurred in a similar stem-loop structure, but the actual cleavage site was in a predicted loop portion and the predicted stability of the overall structure was weak (Figure 2E). The fpiA cleavage site was also in a loop segment, and the predicted secondary structure for this region included a relatively large internal loop region (Figure 2F). Finally, the rnc gene itself was found to have an RNase III cleavage site (see below), and this region showed a stable but complex predicted secondary structure (Figure 2G).

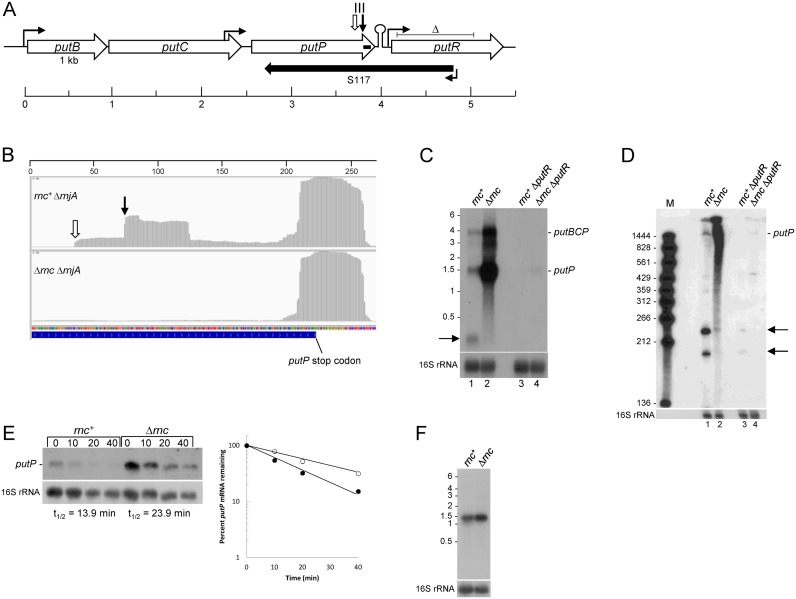

putP mRNA

We investigated further several mRNAs that were newly-identified targets of RNase III. The putP gene encodes a proline transporter and is part of a three-gene operon, putBCP, involved in proline uptake and utilization (Figure 3A). The putBCP operon is transcribed from a promoter that is negatively regulated by CodY in the absence of external proline (45), and positively regulated by PutR in the presence of elevated levels of external proline (45–47). The putP gene is also transcribed from a constitutive promoter that is located in the adjacent putC gene, 140-bp upstream of the putC stop codon (Figure 3A) (45,47). PARE and RLM-RACE data indicated an RNase III cleavage at ∼150-nts upstream from the putP stop codon, with a high RR value of 63.6 (Figure 3B; Table 3). Note that, in both strains, there is a PARE peak near the 3′ end of the putP CDS, which begins about 15-nts upstream of the strong putP transcription terminator structure (ΔG0 = −26.6 kcal/mol). We found such 3′-proximal PARE peaks for many transcription units, and this is explored further below.

Figure 3.

putP mRNA. (A) Schematic of the putBCP operon and regulatory putR gene. CDSs are indicated by rightward open arrows, drawn to scale. Sites of upstream regulated promoter and constitutive internal putC promoter and putR promoter are indicated by hooked arrows. Transcription terminator structure is indicated by a stem-loop. Sites of RNase III cleavage are shown by the downward arrows, as in part B. Extent of S117 antisense RNA is shown by the leftward solid arrow. Extent of the putR deletion is indicated by the ‘delta’ symbol above the putR schematic. Horizontal scale indicates distance (in kb). (B) Integrated genome viewer image from 3′ end of putP CDS in rnc+ ΔrnjA and Δrnc ΔrnjA strains. Site of RNase III cleavage confirmed by 5′ RLM-RACE indicated by the downward arrow. Site of RNase III cleavage inferred from Northern blot analysis indicated by the downward open arrow. Numbers on horizontal scale are nucleotides. (C) Northern blot analysis of putBCP operon RNA in rnc+ and Δrnc strains. The blot is of a MOPS-agarose gel, probed with a 5′-end labeled oligonucleotide complementary to putP CDS 1345–1370 nts (indicated by small bar in putP CDS in Figure 3A). Migration of putBCP operon RNA and putP mRNA indicated on the right. Product of RNase III cleavage indicated on the left by the arrow. Migration of unlabeled RNA size markers (kb) indicated on the left. Lanes 1–2 in wild-type putR strain; lanes 3–4 in ΔputR strain. (D) Northern blot analysis of putP mRNA cleavage by RNase III. Blot is of a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, probed with the same oligonucleotide probe as in part C. Marker lane (M) contained 5′-end-labeled fragments of a TaqI digestion of plasmid pSE420 (66). Migration of putP mRNA and RNase III cleavage products (arrows) indicated on the right. (E) Northern blot analysis of putP mRNA half-life. Above each lane is the time (min) after rifampicin addition. The blot was probed with the same 5′-end labeled oligonucleotide as in part C. Half-life quantitation shown in graph at right: closed circles, rnc+; open circles, Δrnc. (F) Northern blot analysis of putP RNA transcribed from the Pspac promoter. The probe was an oligonucleotide probe complementary to the lacO sequence. Migration of unlabeled RNA size markers indicated on the left.

Northern blot analysis using a 3′-proximal putP oligonucleotide probe was performed on RNA isolated from rnc+ and Δrnc strains grown in the presence of 1 mM proline, an inducing concentration for the putBCP operon. Because the absence of RNase J1 causes a severe slowing of growth rate (Table 2), all Northern blot analyses were done in the rnjA+ background. In the rnc+ strain a ∼1.6 kb band was detected (Figure 3C, lane 1), which is the predicted size of a transcript starting at the putC internal promoter and ending at the predicted Rho-independent transcription terminator. This putP transcript was also observed in a previous report on put operon transcription (47). The full-length putBCP transcript (∼4 kb) is also detectable in the rnc+ strain. An additional small band in the ∼200-nts range was observed in the rnc+ strain only; thus, it is likely the predicted downstream product of RNase III cleavage. The ∼200-nts band detected on the blot from a MOPS-agarose gel was examined in more detail on a blot from a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Figure 3D, lane 1). The results showed two bands of ∼230 and ∼190 nts. The smaller band corresponds well with a fragment extending from the RNase III cleavage site on the downstream side of the putP stem-loop structure (Figure 2B) to the transcription termination site. The larger band is likely the result of RNase III cleavage only on the upstream side of the stem loop structure, for which a PARE peak is visible (Figure 3B) but which had fewer than 100 reads/base and so was not included in Table 3. Although RLM-RACE mapping only detected the downstream 5′ end, the Northern blot data suggest that there are RNase III cleavage sites on either side of the stem-loop shown in Figure 2B, as indicated on the figure.

In the Δrnc strain, the putP transcript was present in ∼15-fold excess over the rnc+ strain (Figure 3B, lane 2; average of two experiments). To explain the difference in putP transcript levels, we first looked at mRNA half-life. The rifampicin experiment in Figure 3E demonstrated a difference in putP mRNA half-life between the two strains; 13.9 min in the rnc+ strain and 23.9 min in the Δrnc strain (average of two experiments). This difference was not great enough to explain the ∼15-fold difference in putP transcript at steady state. We therefore considered whether the absence of RNase III might have a positive effect on transcription from the putP promoter located in putC, although the sequence of this promoter suggests it is a Sigma A-dependent promoter and not subject to regulation (45,47). The putP CDS and transcription terminator were cloned downstream of a Pspac promoter and integrated into the amyE locus. The results in Figure 3F show that under control of the exogenous promoter, there was a 1.9-fold difference in putP RNA levels in the rnc+ and Δrnc strains (average of two experiments), reflecting the half-life difference, as shown in Figure 3E. These results suggest that the 15-fold increase in putP RNA in the Δrnc strain arises from both a direct effect on mRNA half-life due to the absence of RNase III cleavage and an indirect, transcriptional effect.

Finally, putP was one of only a few RNase III targets for which an overlapping antisense RNA has been mapped (43) (Table 3). As shown in Figure 3A, the S117 antisense RNA is transcribed from a promoter located in the putR CDS, and extends well into the putP CDS. To test whether the S117 RNA was required for RNase III cleavage, the pattern of putP mRNA was analyzed in a strain that had an internal putR deletion that included the S117 promoter and 5′ portion of the S117 transcript (Figure 3A) (47). Deletion of putR had a strong negative effect on putP mRNA levels (Figure 3C, lanes 3 and 4), for reasons that remain to be determined. Nevertheless, the results in Figure 3D, lanes 1 and 3, show that RNase III cleavage occurred at the same sites in the presence or absence of S117 RNA transcription, suggesting that the structure recognized by RNase III is intramolecular and not formed by intermolecular base-pairing.

srfA operon

A prominent PARE peak with a relatively high RR value of 36.7 was identified in the srfAA gene, the first gene in the large 27-kb srfAABCD operon that is responsible for B. subtilis surfactin production (Figure 4A, Table 3). The cleavage site was mapped by PARE to 551 nts of the srfAA CDS and confirmed by 5′ RLM-RACE sequencing, which revealed a 5′ end 1 nt away at 550 (Figure 2E, Table 4). The effect on srfA operon RNA was analyzed by Northern blot analysis, using an srfAA 5′-proximal oligonucleotide probe on RNA isolated from rnc+ and Δrnc strains (Figure 4B). Specific bands could not be resolved, likely because the very long operonic RNA is terminated and processed at many sites. Nevertheless, the absence of RNase III resulted in a large increase (∼3.9-fold) in the level of srfA operon RNA in the Δrnc strain relative to the rnc+ strain (Figure 4B; sum of signal from the entire lane). These results suggested that cleavage by RNase III reduces the level of srfA operon mRNA. Because of the indistinct band pattern for srfA operon RNA, we could not reliably perform a half-life measurement in the rnc+ and Δrnc strains.

Figure 4.

srfAA mRNA. (A) Integrated genome viewer image from 440–710 nts of the srfAA CDS, in rnc+ ΔrnjA and Δrnc ΔrnjA strains. 5′ end of the downstream product of RNase III cleavage confirmed by 5′ RLM-RACE is indicated by the downward arrow. Numbers on horizontal scale are nucleotides. (B) Northern blot analysis of steady-state srfA operon RNA in rnc+ and Δrnc strains. The probe was a 5′-end labeled oligonucleotide complementary to 167–195 nts of the srfAA CDS. Migration of unlabeled RNA size markers indicated on the left. (C) Drop collapse assay. rnc and sfp genotypes are indicated above each drop photo.

A drop-collapse assay, which detects surfactin in a cell lysate by the reduction of surface tension in a water droplet, was used to determine whether the increased level of srfAA RNA in the RNase III mutant had a biological effect. Because the B. subtilis 168 strain that was the host strain in these studies is not capable of synthesizing surfactin (sfp genotype), rnc+ and Δrnc strains were created that were sfp+ (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). The qualitative surfactin assay shown in Figure 4C indicated an increased level of surfactin in the medium of the strain lacking RNase III. A semi-quantitative assay of surfactin levels (data not shown; see ‘Materials and Methods’ section) gave approximately a 2-fold increase in surfactin levels in the absence of RNase III. Thus, these results suggest that RNase III is involved, directly or indirectly, in limiting the amount of surfactin in the medium.

The srfA operon is also involved in the development of competence (48), which is due to the presence of the comS gene embedded in the srfAB CDS, the second gene in the srfA operon (49). ComS protein functions to release the ComK transcription factor from an inactive complex, triggering competence development (50). Thus, it was possible that increased srfA RNA in the Δrnc strain might affect competence, as well. However, experiments showed no significant difference in competence levels between rnc+ and Δrnc strains (data not shown).

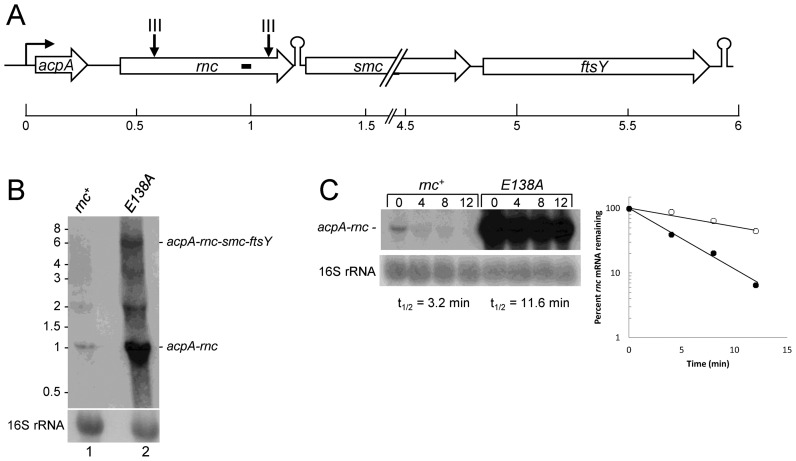

rnc autoregulation

Based on Northern blot analysis in this study (see below), the rnc gene is likely to be the second gene in a ∼6 kb operon consisting of acpA (acyl carrier protein), rnc, smc (involved in chromosome condensation and segregation) and ftsY (a signal recognition particle protein). A predicted Rho-independent transcription terminator sequence is present immediately downstream of the rnc stop codon, suggesting that an acpA-rnc mRNA is also synthesized (Figure 5A). Two PARE peaks were mapped to the rnc gene itself in the rnc+ strain, at around 140 and 650 nts of the CDS (Figure 5A). As the rnc mutant strain used for the PARE protocol was a deletion strain that was missing the entire rnc CDS, there was no comparable PARE data from the Δrnc strain to determine whether these peaks were due to RNase III cleavage. Since RNase III autoregulation of rnc mRNA has been reported in other organisms (22,24,51), we followed up the data from the rnc+ strain by creating a strain that contained the rnc gene with an E138A mutation at the enzyme active site. Such a mutation in the homologous residue of the E. coli enzyme (position 117) results in loss of cleavage activity (52). Indeed, we observed that scRNA processing was completely absent in the strain carrying the E138A mutation (data not shown). Northern blot analysis of the rnc+ strain, using an oligonucleotide probe targeted to a sequence in the rnc CDS, did not detect a clear full-length acpA-rnc-smc-ftsY operon mRNA (Figure 5B, lane 1). Approximately 1.1 kb acpA-rnc mRNA was detected, which was the expected size from the putative acpA promoter to the predicted transcription terminator following rnc. In addition, a band of unknown origin was detected running at ∼2 kb. In the RNase III E138A mutant strain, full-length operon mRNA was easily detected, as well as ∼16-fold increase in acpA-rnc mRNA (Figure 5B, lane 2). The result suggested an autoregulation of RNase III by cleavage of its own mRNA. A rifampicin experiment to determine mRNA half-life showed that acpA-rnc mRNA is short-lived in the rnc+ strain (t1/2 = 3.2 min) and relatively long-lived in the Δrnc strain (t1/2 = 11.6 min) (Figure 5C). The large increase in acpA-rnc mRNA in the strain lacking RNase III is likely due to effects on both transcription and mRNA stability, as we found for putP mRNA.

Figure 5.

rnc mRNA. (A) Schematic diagram of acp operon. Representations are as in Figure 3A. (B) Northern blot analysis of steady state rnc operon RNA in rnc+ and E138A strains. The probe was a 5′-end labeled oligonucleotide complementary to 533–553 nts of the rnc CDS (indicated by small bar in rnc CDS in Figure 5A). Migration of full-length operon RNA and acpA-rnc mRNA indicated on the right. Migration of unlabeled RNA size markers indicated on the left. (C) Northern blot analysis of rnc mRNA half-life. The probe was the same probe as in part B. Above each lane is the time (min) after rifampicin addition. Half-life quantitation shown in graph at right: closed circles, rnc+; open circles, Δrnc.

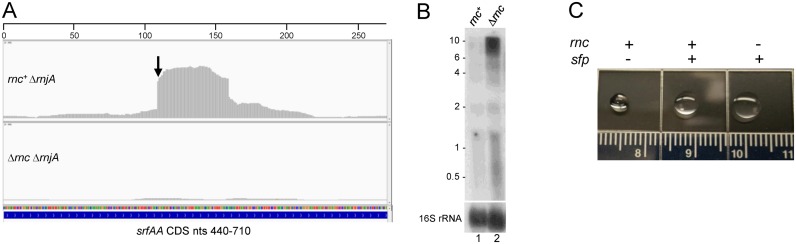

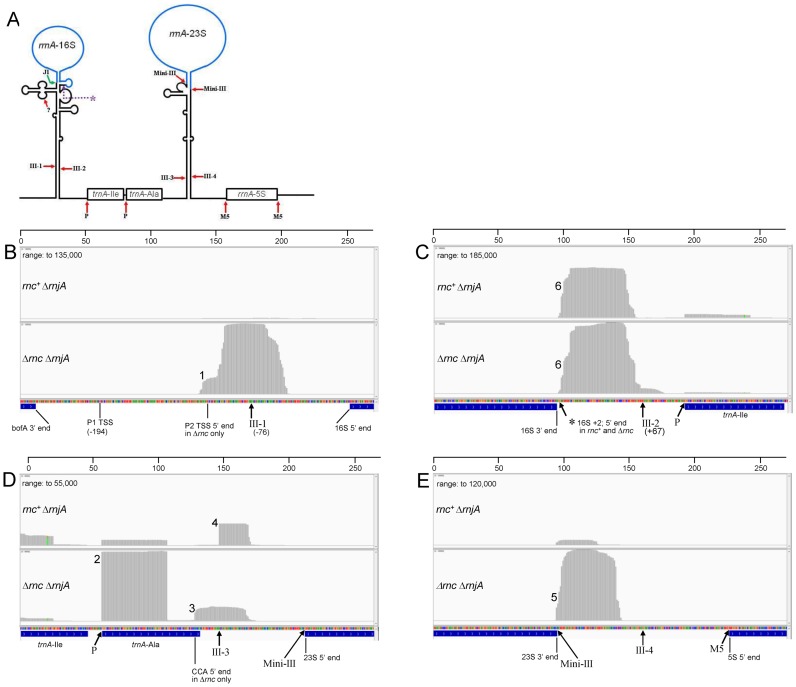

rrn operon RNA processing in the rnc strain

Besides scRNA, the other molecule for which RNase III cleavage was previously documented is ribosomal RNA (cf. schematic in Figure 6A). Although mature rRNA is removed prior to PARE analysis (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section), RNA fragments that contain sequences upstream and downstream of mature rRNA are captured. Because the growth rate of the rnc+ and Δrnc strains was nearly identical (Table 2), we did not expect there to be significant differences in transcription levels of rrn operons between the two strains. In addition, similar results from the different rrn operons indicated that there was no differential depletion of specific rrn operon RNAs. B. subtilis contains 10 rrn operons with differing rRNA/tRNA gene organization; we focused on rrnA. Identical results were obtained for the rrnO operon (data not shown), which has the same rRNA/tRNA structure as rrnA. In the Δrnc mutant strain only, a major PARE peak was observed starting near the P2 promoter TSS (Figure 6B, peak 1) (53). We speculate that RNA transcribed from the upstream P1 promoter is subject to endonuclease cleavage, yielding a 5′ end that is around the P2 TSS. The P2 TSS PARE peak is not detected in the rnc+ strain, perhaps because RNase III cleavage in the 16S processing stalk (site III-1) is followed by 3′ exonuclease activity to degrade the precursor 5′ fragment. A peak similar to peak 1, located near the proximal rrn promoter, was observed for all rrn operons (data not shown).

Figure 6.

PARE analysis of ribosomal RNA. (A) Schematic diagram of rrnA precursor RNA secondary structure and endonucleases involved in rRNA and tRNA maturation. Mature 16S and 23S rRNA in blue. Red arrows point to sites of endonuclease cleavage: III, RNase III; P, RNase P; M5, RNase M5; ?, unknown endonuclease. 16S 5′-end maturation occurs by 5′ exonuclease activity of RNase J1 (hooked green arrow). Endonuclease involved in 16S 3′ end maturation discovered in this study indicated by purple asterisk and dotted line. (B–E) Integrated genome viewer images of rrnA region in rnc+ ΔrnjA and Δrnc ΔrnjA strains, in chromosomal order from upstream of the 16S rRNA sequence (B) to the start of the 5S rRNA sequence (E). Numbers on horizontal scale are nucleotides. The start and end point of mature rRNA and tRNA sequences are labeled below each panel. Arrows point to sites of endonuclease cleavage. Sites of RNase III cleavage are numbered as in part A. The data range was adjusted to show maximum peak heights, and the maximum range is indicated at the top left of each panel. Peaks that are described in the text are numbered 1–6. The site of endonuclease cleavage involved in 16S 3′ end maturation is indicated by the asterisk in part C.

The PARE protocol also revealed peaks that began precisely at the 5′ end of some tRNAs. Two tRNAs (Ile and Ala) are present between 16S and 23S rRNA in the rrnA operon (Figure 6A). The PARE peak representing the 5′ end of trnA-Ala was present at a 12–13-fold higher level in the Δrnc strain compared to the rnc+ strain (Figure 6D, peak 2). A similar result was observed for glycyl tRNA (data not shown). Since the five Ala tRNA genes in rRNA operons have the same sequence, and the mapping program does not distinguish between them, it is not clear whether all Ala tRNAs or only one or several is accumulating in the absence of RNase III. This is not likely to be due to differential selection of tRNAs in the total RNA isolated from the rnc+ and Δrnc strains, since the relative levels of the PARE peak at the 5′ end of trnA-Ile (Figure 6C, right; Figure 6D, left) were inversely related (∼4-fold higher in the rnc+ strain). We have no explanation for why alanyl and glycyl tRNA accumulate to such a relatively high degree in the Δrnc strain. In addition, we observed in the Δrnc strain a significant PARE peak beginning 3 nts from the 3′ end of trnA-Ala (Figure 6D, peak 3). tRNA-Ala ends with a CUCCA↓CCA sequence (downward arrow is the start of the PARE peak), of which the CUCC residues base pair with 4 G's at the 5′ terminus of the tRNA. This 3′ tRNA sequence does not conform to the known substrate requirements for RNase Z (54), and it is not clear why cleavage to remove the encoded CCA sequence would occur, if restoration of the same CCA is required for tRNA function.

Note that in the rnc+ strain, the 5′ end that is due to RNase III cleavage in the upstream portion of the 23S stalk (site III-3) is clearly visible as a PARE peak (Figure 6D, peak 4). As the mature 5′ end of 23S rRNA is determined by Mini-III cleavage (18), this peak likely represents an RNA fragment that extends from the RNase III-3 cleavage site to the Mini-III cleavage site (see Figure 6A). Accumulation of this fragment is relatively low, likely due to 3′ exonucleolytic degradation.

A PARE peak beginning immediately downstream of the mature 23S rRNA sequence was detected in both strains, but was present at a 14-fold higher level in the Δrnc strain (Figure 6E, peak 5). This is likely the 5′ end of a fragment that extends from the Mini-III cleavage site — which yields the mature 23S rRNA 3′ end — to the 5′ end of 5S rRNA, which is generated by RNase M5 (see Figure 6A) (55). In the Δrnc strain, the absence of RNase III cleavage at the III-4 site, in between the Mini-III and RNase M5 cleavage sites, likely stabilizes this fragment.

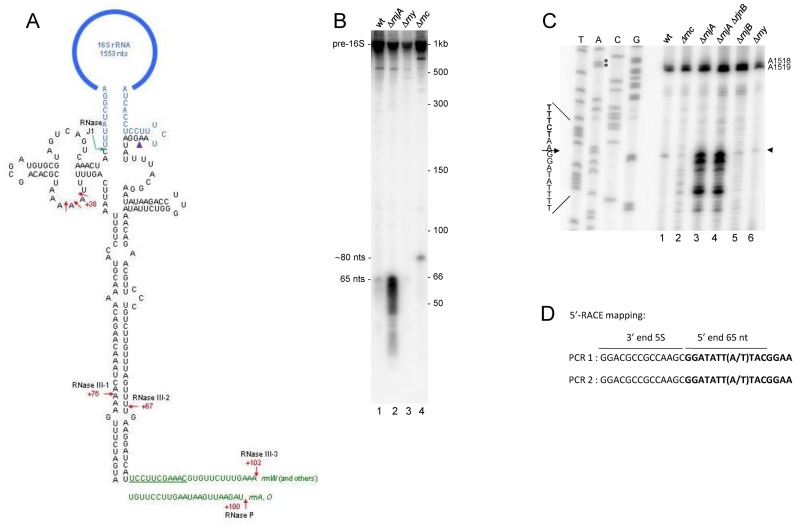

Direct evidence for endonuclease cleavage close to the 16S rRNA 3′ end

A prominent PARE peak was detected in both rnc+ and Δrnc strains beginning 2-nts downstream of the 3′ end of mature 16S rRNA (Figure 6C, peak 6). This peak begins 65-nts upstream of the RNase III cleavage site (site III-2) in the downstream part of the 16S stalk (Figure 7A). Northern blot analysis using a probe directed to the 16S stalk sequence upstream of the RNase III-2 cleavage site revealed a smear of RNA fragments 65 nts and shorter that was clearly observed in an rnjA mutant strain and more faintly in the wild-type strain (Figure 7B, lanes 1 and 2). The 65-nts fragment is hypothesized to extend from an endonuclease cleavage site located 2-nts downstream of the 3′ end of 16S rRNA to the RNase III-2 cleavage site. Presumably, RNase J1 degrades this fragment rapidly from its unprotected 5′ end, which is why it is much less prominent in the wild-type strain. Since the PARE data was derived from rnc+ and Δrnc strains that were also deleted for rnjA, the PARE peak representing this fragment is present in abundance in Figure 6C. The 65-nts fragment was also visible faintly in the rny mutant strain (Figure 7B, lane 3). We have obtained preliminary PARE data also from the rny strain (not shown), and the same PARE peak is present beginning 2-nts downstream of 16S rRNA, confirming that the endonuclease cleavage is not catalyzed by RNase Y. A larger fragment of ∼82 nts was detected in the Δrnc strain (Figure 7B, lane 4). We hypothesize that this fragment extends from a site of cleavage 2-nts downstream of 16S rRNA to the base of the 16S stalk. For rrnA and rrnO operons, in which 16S rRNA is followed by tRNA-Ile, the 3′ end of this fragment would be generated by RNase P cleavage at the 5′ end of tRNA-Ile, followed by 3′ exonuclease chewing back to the base of the 16S stalk (Figure 7A). For all other operons, where 16S rRNA is followed by 23S rRNA, the 3′ end of this fragment may be generated by endonuclease cleavage (possibly RNase Y) in the single-stranded region between the 16S and the 23S processing stalk, followed by 3′ exonuclease chewing back to the base of the 16S stalk (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

(A) Details of 16S processing stalk. The sequence for the rrnW stalk is shown. Mature 16S rRNA sequences are in blue. Numbering is the distance from the mature 5′ or 3′ ends of 16S rRNA. Sites of previously known endonuclease cleavage are indicated by red arrows. RNase J1 processing of 16S rRNA 5′ end is indicated by the green hooked arrow. Site of endonuclease cleavage discovered in this study is indicated by the purple arrowhead. Sequence downstream of the stalk (in green) is shown for rrnW and other operons (top) and for rrnA and rrnO (bottom). For rrnW and other operons, the 16S sequence is followed by the 23S sequence. The underlined sequence is the single-stranded region between the 16S and 23S processing stalks, which may be the target of RNase Y endonuclease cleavage. For the rrnA and rrnO operons, the 16S sequence is followed by two tRNAs (cf. Figure 6A), whose 5′ end is matured by RNase P cleavage. (B) Northern blot analysis of 16S rRNA 3′ fragment, using an oligonucleotide probe complementary to a sequence immediately upstream of the RNase III cleavage site (III-2) in the 16S stalk. Relevant genotype of strains indicated above each lane. Strains used for experiments in Figure 7 are the ‘CCB’ strains listed in Table 1. Migration of precursor 16S rRNA and processed fragments indicated on the left. Migration of unlabeled RNA markers (nts) shown on the right. (C) Primer extension assay for 5′-end mapping of the 65-nts fragment in the indicated ribonuclease mutant strains. Control sequencing lanes of an rDNA fragment are the leftmost lanes. For ease of reading, the sequence readout is written as the reverse complement. Major 5′ end indicated by arrowhead on right. Strong stops at A1518 and A1519 are due to methylation of these residues by KsgA (67). (D) 5′-RACE mapping of the 65-nts fragment. The 65-nts fragment was ligated to 5S rRNA present in total RNA and reverse transcriptase-PCR was performed across the junction. Boldface sequence is from the 65-nts fragment 5′ end. In different operons, the eighth residue is either A or T.

Confirmation of the 5′ end of the 65-nts fragment was obtained by primer extension and 5′ RACE mapping. In Figure 7C, the largest of the specific primer extension products mapped to 2-nts downstream of 16S rRNA. This product is present in much higher abundance in the strains missing RNase J1 (Figure 7C, lanes 3 and 4). Shorter primer extension products may be due to imprecise endonuclease cleavage, which would not be detected in the PARE analysis. 5′ RACE mapping was done on an RNA ligation product between the 65-nts fragment and 5S rRNA (Figure 7D). Sequencing across the junction revealed the same 5′ end, located 2-nts downstream of 16S rRNA. Taken together, these data have revealed that 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation likely involves cleavage by an unknown endonuclease 2-nts downstream of the 16S rRNA sequence, followed by 3′ exonucleolytic trimming to yield the mature 16S rRNA.

Decay of 3′-proximal RNA fragments is highly RNase J1-dependent

In the course of examining PARE peaks that were likely sites of RNase III cleavage, we noticed that a large number of genes had a PARE peak near the end of the CDS; see Figure 3B for an example. As explained above, the rnc+ and Δrnc strains used for the PARE analysis were also deleted for the rnjA gene encoding the 5′ exonuclease RNase J1. We hypothesized that the 3′-terminal PARE peaks were the result of an absence of RNase J1, which is responsible for turnover of fragments containing the transcriptional terminator sequence. Previous work on individual RNAs had indicated such a role for RNase J1 (38). A PARE analysis was also done on a Pspac-rnjA strain that had the rnjA gene transcribed under the control of the IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter. Expression of rnjA driven by the Pspac promoter has been shown in earlier studies to result in 5-fold less rnjA mRNA and RNase J1 protein than when rnjA is expressed from its native promoter (5,56). (A PARE analysis in a strain containing wild-type rnjA has not been performed.) The PARE analyses from these strains provided an opportunity to assess the contribution of RNase J1 to global turnover of 3′-proximal RNA decay intermediates. Genes that were either monocistronic or the last gene in an operon were predicted to show an accumulation of 3′-proximal PARE reads in an rnjA deletion strain. The data in Table 5 show the number of genes with PARE peaks that either contained the stop codon or that began after the stop codon but before the following CDS. In the strain that was deleted for rnjA, greater than half of monocistronic genes and last genes in an operon (54.8 and 54.5%, respectively) showed a PARE peak in the area of the stop codon. The percentages of monocistronic genes and last genes in an operon that showed 3′-proximal PARE peaks were reduced about 2-fold in the Pspac-rnjA strain grown in the presence of IPTG and containing a low level of RNase J1 (26.7 and 31.8%, respectively). On the other hand, for genes located elsewhere in operons, only 14–15% showed a 3′-proximal PARE peak. Importantly, for this latter category there was no significant difference in the percent of genes with a 3′-proximal PARE peak between the strain with no RNase J1 and the strain with low RNase J1 (14.5 and 14.7%, respectively; Table 5). These results strongly support the hypothesis that RNase J1 is globally involved in the turnover of 3′-terminal fragments.

Table 5. 3′-proximal PARE peaks.

| Number of genes with 3′-proximal peak (percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene category | Number of genesa | ΔrnjA strain | Pspac-rnjA strain |

| Known operonic locationb | 1562 | 608 (38.9) | 360 (23.0) |

| Monocistronic | 622 | 341 (54.8) | 166 (26.7) |

| Last in operon | 327 | 178 (54.5) | 104 (31.8) |

| Not monocistronic, not last in operon | 613 | 89 (14.5) | 90 (14.7) |

aGenes with >1 read/base in a standard RNA-Seq analysis in either strain.

bBased on BsubCyc transcription unit information.

DISCUSSION

In this report, a comparison of endonuclease cleavage sites in B. subtilis strains containing or missing the rnc gene allowed mapping of RNase III cleavage sites in multiple RNAs. The list of 53 CDS and 5 intergenic RNase III targets in Table 3 likely represents a subset of the actual RNase III cleavages in the transcriptome. We used stringent criteria to differentiate RNAs that are direct RNase III targets from RNAs that are downregulated transcriptionally in the rnc strain (see description of the RR value in ‘Results’ section). It is likely that other genes for which we observed PARE peaks, but which did not conform to the criteria used, are also RNase III targets. Another factor that probably limited the number of genes identified as RNase III targets was that the PARE protocol depends on ligation of a 5′ adaptor to a monophosphorylated end, which may not be efficient depending on the potential for RNA folding at the 5′ end. Thus, our findings suggest that, in addition to processing of the stable RNAs, scRNA and rRNA, many mRNAs are subject to RNase III cleavage. A similar conclusion was arrived at in studies of RNase III targets in other organisms (24,27,29,30,57). The Sim et al. study (57) employed E. coli strains with tunable RNase III expression rather than a knockout strain in order to avoid indirect effects of loss of RNase III, and they found a total of 87 upregulated and 100 downregulated genes that were apparently direct targets of RNase III.

In the S. aureus studies cited above (24,30), RNase III cleavage was found most often to be associated with antisense RNAs, suggesting that double-stranded RNA targets were formed by intermolecular base-pairing. Indeed, the Lasa et al. analysis of B. subtilis RNAs (30) suggested that this was the case in this organism as well. However, for the target sites mapped in our study, we found little evidence that RNase III targeting required antisense RNA pairing. Only four of the targeted genes were located in a genomic region with known antisense RNAs that overlapped with the cleavage sites (43). We showed that one of these—the S117 antisense RNA that overlaps the putP CDS—was dispensable for RNase III cleavage (Figure 3D). Thus, it appears that the overwhelming majority of mapped RNase III targets are formed by intramolecular base-pairing.

Of the six RNase III target sites that were confirmed by 5′ RLM-RACE analysis (Figure 2), a single 5′ end was observed in three of the cases, whereas more than one 5′ end located in the vicinity of the PARE cleavage site were obtained in the other cases (Table 4). It is possible that RNase III cleavage is not precise, and may cleave at more than one residue. Indeed, structural studies of the Aquifex aeolicus RNase III by Court et al. have recently revealed alternate cleavage sites for a single substrate (13). However, this is apparently uncommon, and is not likely to explain the multiple 5′ ends obtained by 5′ RLM-RACE analysis in our work. Rather, we speculate that additional 5′ exonuclease activities may be present in the rnjA deletion strain that ‘nibble’ at the 5′ ends generated by RNase III cleavage, resulting in additional 5′ ends in some cases.

Two of the fully-mapped RNase III cleavage sites occurred in loop sequences as predicted by mfold (Figure 2). This is not typical of E. coli RNase III cleavage sites, as has been studied in detail by Nicholson et al. (14). It may be that the predicted structures are not the only ones possible. In addition, the mapped 5′ end may be due to exonucleolytic digestion that occurs after RNase III cleavage. We note that atypical RNase III cleavage sites were also suggested in a study of S. coelicolor targets (29). While many studies of model E. coli RNase III substrates have yielded rather strict rules for sequence/structure that provide for optimal cleavage, it may be the case that natural substrates have uncharacterized features that make them RNase III targets. It has become clear only in the last few years that many native mRNA CDSs contain RNase III target sites, and therefore these substrates have not been studied yet in detail. In addition, RNase III enzymes from different organisms may have altered specificities, as we showed previously in in vitro experiments with purified E. coli and B. subtilis RNase III enzymes (20). To learn more about the requirements for B. subtilis RNase III target site recognition, it will be necessary to analyze by in vitro assays several of the natural substrates identified in this study and for which the secondary structure has been confirmed by structure-probing experiments.

For three of the mRNAs that were cleaved by RNase III, we showed an effect on the steady-state levels of mRNA, with much lower levels in the rnc+ strain. In the case of putP and rnc, we found that this is only partially a result of an increase in mRNA half-life in the absence of RNase III. For mRNA targets of RNase III, it is likely that modulation of mRNA levels is achieved by a combination of transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Lasa et al. have suggested that RNase III functions to modulate levels of sense RNAs (30). Whether this occurs solely as a direct consequence of RNase III cleavage will require further investigation of individual mRNAs.

The PARE analysis afforded the opportunity to learn about decay of mRNA fragments that contain the Rho-independent transcription terminator sequence followed by a run of U residues, which are inherently resistant to binding and/or decay by 3′ exonucleases. In organisms that do not contain a 5′ exonuclease, such as E. coli, the mechanism for turnover of 3′-end-containing fragments involves polyadenylation at the 3′ end to allow binding and processive decay by RNase R or reiterative binding and decay by PNPase (reviewed in (58)). Based on our observation of increased 3′-end-containing fragments for three RNAs in strains depleted of RNase J1 (38), we hypothesized that organisms that contain a 5′ exonuclease rely on such an activity for the turnover of 3′-terminal fragments. While a significant percentage of B. subtilis mRNAs are known to be polyadenylated, even more so than in E. coli (59), the B. subtilis polyadenylating enzyme has not yet been identified (60), making it impossible to study the role of polyadenylation in mRNA decay. The results in Table 5, which showed a large increase in PARE peaks at 3′ ends of transcripts in the rnjA deletion strain, clearly demonstrate the global role that RNase J1 plays in the turnover of 3′-end-containing fragments. Thus, degradation of 3′-terminal fragments for many B. subtilis mRNAs likely involves one or more endonuclease cleavages upstream of the stop codon, followed by RNase J1 turnover of the downstream products.

The PARE analysis was revealing as far as 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation is concerned. The mechanism for bacterial 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation has been debated for years, and is still not resolved, even for the well-studied E. coli. In E. coli, RNase III cleaves 33-nts downstream of the mature 3′ end. As processing intermediates with <33-nts downstream of the 16S rRNA 3′ end have not been detected, it had been assumed for a long time that the 3′ end of 16S rRNA is generated directly by cleavage catalyzed by an unidentified endonuclease (reviewed in (61)). More recently, evidence for E. coli 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation by exonucleolytic trimming has been published (39). These authors found that the absence of multiple 3′ exonucleases results in the accumulation of precursor 16S rRNA with a 33-nts 3′ extension. Similarly, studies in Pseudomonas syringae have suggested that RNase R, a 3′ exonuclease, is required for 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation, most likely by chewing back from the site of downstream RNase III cleavage (62). However, another view of 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation has been proposed by Walker et al., based on their work with the YbeY protein, a highly conserved bacterial protein whose absence in E. coli results in pleiotropic phenotypes. This group showed initially that ybeY mutants were defective in processing of all three rRNAs, and ybeY mutant strains that carried additional mutations for the 3′ exonucleases RNase R or PNPase had little mature 16S rRNA (63). More recently, the same group showed that YbeY has single strand-specific endonuclease activity (64). These authors suggested that E. coli 16S rRNA 3′ end maturation may involve YbeY endonuclease cleavage. Details of 16S rRNA 3′ maturation in B. subtilis have not been addressed. We show here by PARE analysis in rnc+ and Δrnc strains (Figure 6) and by northern blot and RACE analysis (Figure 7) the first direct evidence for endonuclease cleavage in the final or near-final maturation of B. subtilis 16S rRNA. Cleavage occurs 2-nts downstream of the mature 16S rRNA 3′ end, and is presumably followed by exonucleolytic trimming to complete the maturation process. The endonuclease cleavage close to the 16S rRNA 3′ end identified here cannot be due to YbeY, as 5′ ends detected in the PARE must begin with a 5′ monophosphate and YbeY activity leaves a 5′ hydroxyl (64). The fragment extending from the 16S rRNA 3′-proximal endonuclease cleavage site to the RNase III cleavage site (III-2) was barely detectable in the wild-type strain but clearly visible in the rnjA deletion strain (Figure 7B), indicating that it is rapidly degraded by RNase J1. It is possible that degradation of the fragment generated from the downstream side of the 16S stalk is required to allow exonucleolytic maturation of the 16S rRNA 5′ end by RNase J1 on the upstream side of the 16S stalk (65). The search for the endonuclease activity responsible for near final maturation of 16S rRNA in B. subtilis is ongoing.

ACCESSION NUMBER

Raw PARE data and RNA-Seq data are available at the NCBI GEO database, accession number GSE77217.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Boris Belitsky for advice and for the putR deletion strain.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [GM-100137 to D.H.B.]; CNRS [UMR 8261]; Université Paris VII-Denis Diderot; the Agence Nationale de la Recherche [ANR-12-BSV6-007-asSUPYCO, ANR-11-LABX-0011-01-Dynamo to C.C.]; Department of Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (in part). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health [GM-100137].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bechhofer D.H. Bacillus subtilis mRNA decay: new parts in the toolkit. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011;2:387–394. doi: 10.1002/wrna.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehnik-Habrink M., Lewis R.J., Mader U., Stulke J. RNA degradation in Bacillus subtilis: an interplay of essential endo- and exoribonucleases. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;84:1005–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durand S., Gilet L., Bessieres P., Nicolas P., Condon C. Three essential ribonucleases-RNase Y, J1, and III-control the abundance of a majority of Bacillus subtilis mRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condon C. What is the role of RNase J in mRNA turnover. RNA Biol. 2010;7:316–321. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.3.11913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu B., Deikus G., Bree A., Durand S., Kearns D.B., Bechhofer D.H. Global analysis of mRNA decay intermediates in Bacillus subtilis wild-type and polynucleotide phosphorylase-deletion strains. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;94:41–55. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piton J., Larue V., Thillier Y., Dorleans A., Pellegrini O., Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Vasseur J.-J., Debart F., Tisne C., Condon C. Bacillus subtilis RNA deprotection enzyme RppH recognizes guanosine in the second position of its substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:8858–8863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221510110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh P.-K., Richards J., Liu Q., Belasco J.G. Specificity of RppH-dependent RNA degradation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:8864–8869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222670110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figaro S., Durand S., Gilet L., Cayet N., Sachse M., Condon C. Bacillus subtilis mutants with knockouts of the genes encoding ribonucleases RNase Y and RNase J1 are viable, with major defects in cell morphology, sporulation, and competence. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:2340–2348. doi: 10.1128/JB.00164-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards J., Liu Q., Pellegrini O., Celesnik H., Yao S., Bechhofer D.H., Condon C., Belasco J.G. An RNA pyrophosphohydrolase triggers 5′-exonucleolytic degradation of mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bechhofer D.H. Nucleotide specificity in bacterial mRNA recycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:8765–8766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307005110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deana A., Belasco J.G. Lost in translation: the influence of ribosomes on bacterial mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2526–2533. doi: 10.1101/gad.1348805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glatz E., Nilsson R.P., Rutberg L., Rutberg B. A dual role for the Bacillus subtilis glpD leader and the GlpP protein in the regulated expression of glpD: antitermination and control of mRNA stability. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;19:319–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.376903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Court D.L., Gan J., Liang Y.H., Shaw G.X., Tropea J.E., Costantino N., Waugh D.S., Ji X. RNase III: genetics and function; structure and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013;47:405–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson A.W. Ribonuclease III mechanisms of double-stranded RNA cleavage. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2014;5:31–48. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herskovitz M.A., Bechhofer D.H. Endoribonuclease RNase III is essential in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;38:1027–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oguro A., Kakeshita H., Nakamura K., Yamane K., Wang W., Bechhofer D.H. Bacillus subtilis RNase III cleaves both 5′- and 3′-sites of the small cytoplasmic RNA precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19542–19547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathy N., Benard L., Pellegrini O., Daou R., Wen T., Condon C. 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity in bacteria: role of RNase J1 in rRNA maturation and 5′ stability of mRNA. Cell. 2007;129:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redko Y., Bechhofer D.H., Condon C. Mini-III, an unusual member of the RNase III family of enzymes, catalyses 23S ribosomal RNA maturation in B. subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:1096–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panganiban A.T., Whiteley H.R. Bacillus subtilis RNAase III cleavage sites in phage SP82 early mRNA. Cell. 1983;33:907–913. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitra S., Bechhofer D.H. Substrate specificity of an RNase III-like activity from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:31450–31456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durand S., Gilet L., Condon C. The essential function of B. subtilis RNase III is to silence foreign toxin genes. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardwell J.C., Regnier P., Chen S.M., Nakamura Y., Grunberg-Manago M., Court D.L. Autoregulation of RNase III operon by mRNA processing. EMBO J. 1989;8:3401–3407. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsunaga J., Dyer M., Simons E.L., Simons R.W. Expression and regulation of the rnc and pdxJ operons of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;22:977–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lioliou E., Sharma C.M., Caldelari I., Helfer A.C., Fechter P., Vandenesch F., Vogel J., Romby P. Global regulatory functions of the Staphylococcus aureus endoribonuclease III in gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regnier P., Portier C. Initiation, attenuation and RNase III processing of transcripts from the Escherichia coli operon encoding ribosomal protein S15 and polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;187:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robert-Le Meur M., Portier C. E.coli polynucleotide phosphorylase expression is autoregulated through an RNase III-dependent mechanism. EMBO J. 1992;11:2633–2641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stead M.B., Marshburn S., Mohanty B.K., Mitra J., Castillo L.P., Ray D., van Bakel H., Hughes T.R., Kushner S.R. Analysis of Escherichia coli RNase E and RNase III activity in vivo using tiling microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3188–3203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lybecker M., Zimmermann B., Bilusic I., Tukhtubaeva N., Schroeder R. The double-stranded transcriptome of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:3134–3139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315974111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatewood M.L., Bralley P., Weil M.R., Jones G.H. RNA-Seq and RNA immunoprecipitation analyses of the transcriptome of Streptomyces coelicolor identify substrates for RNase III. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:2228–2237. doi: 10.1128/JB.06541-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasa I., Toledo-Arana A., Dobin A., Villanueva M., de los Mozos I.R., Vergara-Irigaray M., Segura V., Fagegaltier D., Penades J.R., Valle J., et al. Genome-wide antisense transcription drives mRNA processing in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:20172–20177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113521108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.German M.A., Pillay M., Jeong D.H., Hetawal A., Luo S., Janardhanan P., Kannan V., Rymarquis L.A., Nobuta K., German R., et al. Global identification of microRNA-target RNA pairs by parallel analysis of RNA ends. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]