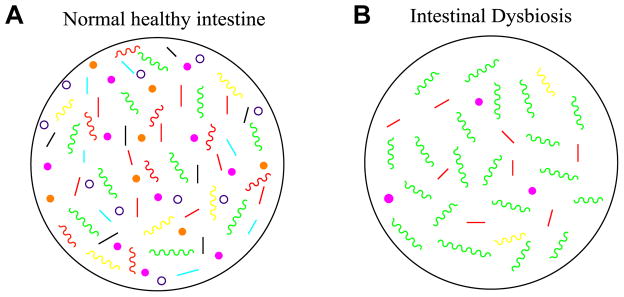

Figure 1. Normal and dysbiotic intestinal microbiota.

A. The healthy intestines of normal individuals are colonized by a wide range of bacteria of over 1000 species. In healthy individuals, these bacteria are in a homeostatic balance between commensal and potentially pathogenic bacteria, and the intestinal tract does not display overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria. The microflora provide the host with protection from foreign microbes, acting as a central line of resistance to colonization by these exogenous bacteria. This protection is known as the “barrier effect”, or colonization resistance [1]. Through the mucosal surface of the intestine, the microbiota interacts with the host immune system, providing the host with immune regulatory functions, like priming the mucosal immune system [1,2]. The microbiota also possesses various metabolic functions, like breaking down complex carbohydrates and generating short-chain fatty acids, which the host benefits from [1, 3]. Surprisingly, the gut microbiota is also capable of interacting with distant organs, such as the brain, which has led to studies of the influence of the gut microbiota on mental disorders, like autism, and diseases such as Alzheimer’s [2].

B. When the intestinal bacterial homeostasis is disrupted, dysbiosis occurs. Dysbiosis is defined by an imbalance in bacterial composition, changes in bacterial metabolic activities, or changes in bacterial distribution within the gut. The three types of dysbiosis are: 1) Loss of beneficial bacteria, 2) Overgrowth of potentially pathogenic bacteria, and 3) Loss of overall bacterial diversity. In most cases, these types of dysbioses occur at the same time. Green colors representing pathogenic bacteria and each different color bacteria representing a different commensal species to show diversity or lack thereof in each case. Dysbiosis has been associated with diseases such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Obesity, Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes, Autism, and certain gastrointestinal cancers.