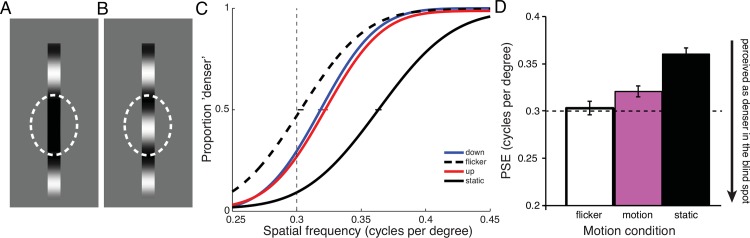

Fig 5. Experiment 4.

Do moving stimuli that extend through the blind spot appear filled-in using luminance information from the blind spot borders (A), or does filling-in use information from the grating’s structure (B)? B shows a schematic of stimuli employed in Experiment 4. Observers viewed a grating reaching through the blind spot that was flickering, drifting up or down, or remaining stationary. The grating’s spatial frequency was varied from trial to trial, and observers judged its apparent density by comparing it to a flickering grating in another interval, whose spatial frequency was always fixed at 0.3 cycles per degree. C Aggregate psychometric functions for 4 observers (8 eyes), showing responses as a function of spatial frequency for flickering, upward, downward drifting, and static gratings. D Means of individual PSEs (with SEMs). Static gratings with a physically higher spatial frequency appeared perceptually matched in density to a flickering grating of 0.3 cycles per degree. In other words, a static grating’s perceptual density was grossly underestimated. Moving gratings also needed increased spatial frequency to appear perceptually matched, but were perceived more accurately than static gratings.