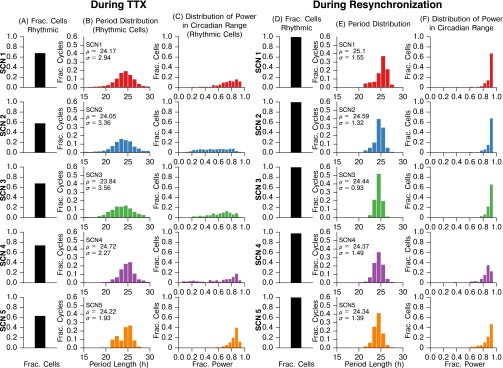

Fig. S1.

Summary statistics for SCN slices during TTX application and during resynchronization. (A and D) Fraction of cells which displayed rhythmic circadian oscillation (A) during TTX or (D) during resynchronization. Not all cells observed during resynchronization could be tracked during TTX due to very low luminescence (as in ref. 36); cells that could not be tracked were classified as arrhythmic. We found that chemically uncoupled cells are nondeterministic, weak oscillators, in accordance with ref. 36. When recoupled after TTX washout, nearly all cells observed became rhythmic. A cell was determined to be rhythmic if it exhibited a Lomb–Scargle periodogram peak between the 18- and 32-h period at significance. Data were baseline detrended via discrete wavelet transform. (B and E) Period length histograms (B) during TTX application and (E) during resynchronization. As period varies cycle-to-cycle for decoupled oscillators and during resynchronization, we report each peak to peak period of oscillation for each cell, rather than finding the mean period of a cell through fitting a sinusoid. Peak times were identified by a discrete wavelet transform filtering for peaks with period between 16 and 32 h. (C and F) Histograms of the fraction of oscillatory power in the circadian frequency range (16–32 h) (C) during TTX or (F) during resynchronization, calculated via fast Fourier transform. Data were baseline detrended before FFT. We note that not all cells are observable during TTX due to low bioluminescence, and thus column C includes only rhythmic, observable cells. For all SCNs, the period distribution tightened and more oscillatory power was in the circadian range during resynchronization. As these effects and distributions are consistent across SCNs during resynchronization, a cross-comparison may be used to control FPR.