Abstract

Baltimore mother Toya Graham became a viral video sensation after being filmed yelling at and hitting her teen son. Graham, who is Black, was trying to stop her son from joining the protests following Freddie Gray’s death in police custody in Baltimore in April 2015. Dubbed “mother of the year,” news outlets applauded Graham for her fierce determination to keep her son out of harm’s way by any means necessary. The media and ensuing public response to the video are illuminating for what they say about cultural notions of Black motherhood: the good Black mom should be superstrong to protect her children, but she is also responsible for controlling her children and preventing them from getting into trouble. In celebrating Graham, the media was implicitly condemning all the other mothers whose children participated in the protests—that is, the mothers who did not prevent their children from “senseless” rioting against institutional racism in policing.

According to the social theorist Patricia Hill Collins, the superstrong Black mom has long been a stereotypical image of Black mothers. Initially emerging from Black communities’ valorization of Black mothers’ intensive efforts to raise their children and shield them from the dangers of living with racism and poverty, the superstrong Black mother image now dictates the terms of good mothering for Black women: be strong and be solely responsible. The modern emphasis on individual responsibility as a solution to structural problems reinforces this idea. This context presents extraordinary challenges for Black mothers as they attempt to protect their children from the dangers of institutionalized racism. The nearly 50 low-income urban Black mothers of teenagers we interviewed in North Carolina and New York described the multiple strategies they use to insulate their children from danger—strategies that also bring stress and hardship to the mothers themselves. About half the mothers we spoke with are partnered but we focus exclusively on the mothers’ parenting experiences here. Their stories reveal the staggering odds they are up against as they and their children confront the realities of historical and ongoing racial discrimination.

The long-held superstrong Black mother image, Patricia Hill Collins argues, now dictates the terms of good mothering for Black women: be strong and be solely responsible.

Mothers’ Common Grief

Raising kids is hard, but raising children who face daily assaults on their very being is especially hard. In a study tracking a nationally representative group of mothers of children from kindergarten to third grade, researchers Kei Nomaguchi and Amanda House found that only Black mothers experienced heightened levels of parenting stress as their children grew older and mothers’ concerns about their safety and survival increased. Recent analyses by statistician Nate Silver underscore how dangerous the U.S. is for Black Americans, who are almost eight times as likely as White Americans to be homicide victims.

Malaya, a New York mother of three, is a heartbreaking example of this reality. When asked in an interview about recent major events in her life, she said her 26 year-old son had been murdered three weeks ago while trying to break up a fight at a house party. “My son passed away at the same age as his father. He passed away two blocks from where his father got murdered,” she somberly related. Malaya’s son’s death has made her even more worried about the safety of her two younger children.

The day before her son was murdered, Malaya joined a community gym with plans to lose weight because she was experiencing some health problems she wanted to manage: stress, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Since she received the late night phone call about her son’s death, she has not returned to the gym. Instead, she has been focused on getting justice for her dead son and insulating her two remaining children from danger. Especially since her son’s death, Malaya tries to teach her 16-year-old daughter Nina to keep to herself and not to trust anyone. “I be just so afraid with my daughter outside now, even around friends. And she is like ‘Ma, would you want me to be in the house forever?’ No I just, I don’t even know how to even put it like…. Friends are friends, but your life is more important.”

Malaya encourages Nina to avoid becoming too close to anyone. Her personal philosophy is “go to work, come home, take care of the house, do what you’ve got to do. All that mingling in the streets is only going to cause trouble.” She takes this approach in her own life: “I can’t even trust my own friends. I don’t have nothing against them, but I don’t know what’s their motive. I want Nina to understand it. Because when you came out of my womb you came out alone. So there’s always a boundary that you got to know.” Malaya instructs Nina to avoid all unnecessary social contact and stay inside their apartment, hoping this will save her life.

Malaya’s third child is a 3-year-old son. Even prior to her older son’s murder, Malaya was concerned about the safety of her youngest son. To insulate him from danger, Malaya spoke of her interest in homeschooling: “I was really scared to let him out. I’m like that because I’ve seen what happens when someone gets out.” A social worker convinced Malaya to enroll her son in public preschool, but she is strict about his socializing: “I don’t have him with no friends. He goes to school on the bus, he comes home on it.”

Malaya’s story captures several aspects of the unfortunately common experiences of low-income Black mothers: losing a child, living in unsafe neighborhoods owing to subsidized housing policies which intensified poverty and racial segregation, deep social distrust and disenfranchisement, and profound efforts to insulate and protect their children. Her story also demonstrates the impact stress and self-sacrifice can have on mothers’ health. Reflecting on how her son’s murder affected her life, she said: “And me, all I just wanted is just to live a normal life and just be normal. I want to go to the gym.”

Safety from the Streets, Safety from the Law

Not only do Black Americans have high homicide rates, they are also disproportionately arrested and incarcerated, leading legal scholar Michelle Alexander to argue that Black incarceration rates reflect a legacy of discriminatory laws and policies, such as racial profiling, the heavy police presence in low-income Black neighborhoods, and the war on drugs, which involved higher prison sentences for possession of crack cocaine (more common among Blacks) than cocaine (more commonly used by Whites) though there is no chemical difference between them.

With one in nine Black men behind bars, Black mothers worry about their children, especially their sons, ending up on the wrong side of the criminal justice system. Vivian, a New York mother of two boys, worried that her 17-year-old son Dixon would end up in jail or dead. Her fears led her to ask him: “Which one do you want to be, a name or a number? What I mean by that is, like, what do you want? A job or you want to go to jail?” Likening Dixon’s social environment to crabs trapped in a bucket, Vivian said she had to pull him out and separate him from his friends: “You ever saw like a bucket of crabs, and you pull the crabs up, what is the other crab doing? Yeah, they are holding on. It’s always going to be somebody that’s going to try to pull you down you know, but if you have a strong family behind you, they’re going to break that arm. You know what I’m saying? And that’s what the hell I did, I broke that arm. Yeah, and pushed those friends away from him. And look at him now, he’s out there working.” Vivian intervened to end her son’s relationship with friends she worried would expose him to the long arm of the law, and Vivian’s brother offered her son a job in his moving company, an option not available to many low-income urban Black youth who face bleak employment prospects.

Like Malaya, Vivian keeps to herself and encourages the same for her children, sending them away from the neighborhood as frequently as possible to “show my kids there’s a different world out of this place. I know it’s nothing but poverty up and down here, but if you can choose to walk outside of this, you will see a different world. I take my kids to 42nd Street, to do things upstate, somewhere out the house, things like that. To Virginia to go see my brothers….” One in four Black Americans live in neighborhoods marked by extreme poverty thanks to a host of federal, state, and local housing policies that concentrate poverty in pre-existing low-income areas. Moreover, these policies are racially-based: Poor Blacks are much more likely than poor Whites to live in neighborhoods characterized by extreme poverty, crumbling infrastructure, and minimal job opportunities. When they are at home, Vivian tries to ensure her sons’ safety by keeping them inside and occupied with video games. “If the [video] game keeps them from out of the street, they can play it all day, you know. Hey, if they keeps them under me, under my eye watch, go right ahead. I’m not saying all day, but it keeps them here, you know.” Vivian’s awareness that too much screen time is unhealthy for children is tempered by her fears for her sons’ safety outdoors and away from her watchful eye.

Raising kids is hard, but raising children who face daily assaults on their very being is especially hard.

Adrianna also worries about her children’s safety outside their home. We interviewed Adrianna in North Carolina following her move from the northeast in the hopes of finding asafer place to raise her children. The mother of three explained safer place to raise her children. The mother of three explained that even so she is vigilant: “I keep very close eyes on my children. They can’t be wandering the neighborhood. I need to know where my kids are at. If they’re going somewhere with other children, I need to talk to the parents. Who’s gonna be supervising them?” Only half-jokingly, Adrianna went on to say that she won’t let her children leave the house without the “phone numbers, addresses, and social security numbers” of their friends’ parents.

In addition to being vigilant to insulate their children from neighborhood dangers, Black mothers also find themselves advocating for their children in racist institutional contexts such as schools. Adrianna recounted the forms of racial discrimination her three children have faced in school since their move to North Carolina. A recent analysis of federal school data by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that, even as Black children represent less than a quarter of the student body in North Carolina and 12 other southern states, they make up about half of all expulsions and suspensions. At the time of her interview, Adrianna’s 11-year-old son was facing a possible suspension for violating the dress code with his Mohawk hairstyle, which Adrianna defended as “a part of who we are as a people.” In her frustration with the school system, Adrianna, like Malaya, is considering taking her children out of school to homeschool them. Their interest in homeschooling mirrors a larger trend of homeschooling becoming more popular among Black families as they try to insulate their children from discriminatory treatment.

Blaming Mothers

“I’m not one of those parents who is laxaditty,” emphasized Adrianna, distancing herself from the stereotype of the bad mother. “I have always been a mother first. I don’t put anything above my children’s lives,” she said. Black mothers across the income spectrum have to deal with the negative connotations of stereotypes about them as mothers and the stress of raising Black children in a racist society. In separate works, sociologists Dawn Dow and Karen McCormack found that the controlling images of Black women, such as the welfare queen and the strong Black woman, influence how both poor and middle-class Black mothers make parenting decisions, and create a sense of exclusion from White motherhood.

In her book on racial bias in the child welfare system, Dorothy Roberts, an eminent scholar of race, gender, and the law, argues that stereotypes of poor Black women as bad mothers mean that they are more heavily monitored by the state and their mothering is treated with suspicion. Racial bias can infuse even teachers’ perceptions of Black mothers. A 2012 study by Susan Dumais and her colleagues found that elementary school teachers viewed Black parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling negatively, while interpreting White parents’ involvement positively. Similarly, the Black mothers we spoke with whose children were involved with state institutions—including public schools and the criminal justice system—discussed the ways their mothering was assumed to be inadequate by institutional practices.

Vivian’s awareness that too much screen time is unhealthy for children is tempered by her fears for her sons’ safety outdoors and away from her watchful eye.

Several of the mothers spoke of their sons’ entanglement with the court system in particular. As researchers Victor Rios, Nikki Jones, and others have observed, the institutions that surround Black children are eager to discipline and lock them up; when they do, their mothers also come under the authority of the criminal justice system. Tiana “felt like I was the one that committed the crime,” when she recounted the things she had to do in order to meet the conditions of her 14-year-old son’s probation for kicking a motorcycle, such as attending Saturday morning classes and advocating for him in the system. When a judge threatened to put her son on probation for another six months, Tiana said, “I was like, what? Uh-uh. I had to take him to all them little, you know, classes and it was cutting out time for my other kids.” Tiana agreed to attend even more classes with her son, however, to demonstrate her commitment as a mother and to keep him from receiving an additional sentence.

When Mariah’s 15-year-old son was caught trying to steal a moped, a condition of his probation was that Mariah had to take weekly parenting classes. She explained, “They send a guy over here to do a parenting class with us every Saturday. He shows us some videos of other parents and their children, going through probably the same things [and teaches us] maybe the different things that maybe I can do instead of yelling and screaming.” Mariah described the classes as “sometimes” helpful but noted that they don’t address what to do when she tells her son “don’t go or you can’t go outside today. Soon as you turn your back, he’s out the door, like you didn’t tell him nothing.”

All too often the mothers’ stories underscored how state institutions and policies positioned mothers as suspect parents but also solely responsible for their children’s behavior. Tiffany’s 16-year-old son Corey was in trouble for skipping school, for which the school blamed Tiffany. “I don’t understand how they want to blame the parents for the kids when you send them out there to go to school,” she said, explaining that both the school and the law punished her for Corey’s truancy even though she made sure he was out the door with his school clothes and backpack every day. “I get like a phone call telling me that it is mandatory that I makes the school meeting…. Basically they were telling me [the principal] was going to call ACS (Administration for Child Services) on me because Corey is not coming to school. I was like, I have a seven year old and you can check, he has perfect attendance. So you cannot fault me for his mistakes.” They did however fault her, subjecting her to an embarrassing 30-day investigation involving multiple home visits by ACS workers.

Praise and Punishment

Highly publicized recent incidences of police brutality have highlighted persistent racism and the ongoing challenges of being Black in America. Black mothers not only fear for their children each time they step outside the door, they also encounter gender, class, and racial discrimination of their own, including stereotypes about them as mothers. The women we interviewed proudly spoke of their strength and the sacrifices they have made to insulate their children from the surrounding dangers, but as their stories demonstrate, these efforts stem from living in impossible conditions created by state policies and practices, and they are often not enough. Praising mothers for being superstrong also makes it easy to lay the blame for children’s hardships at mothers’ feet.

The US welfare state is shrinking while an emphasis on small government grows, inspired and perpetuated by inaccurate understandings of the causes of poverty and by racist stereotypes about those who use social programs. State and institutional supports for poor families that do exist tend to focus on what mothers are doing wrong and how they could be better parents. This reflects a larger trend of shifting responsibility onto the individual, illustrated in the stories we presented above. The mothers we interviewed described how state involvement in their lives was at best neglectful and at worst exacerbated the parenting challenges and stress they faced. It’s no surprise then that they see little choice but to be hypervigilant, separating their children from their peers, keeping them inside, and trying to get them away from the surrounding dangers, including discriminatory treatment.

Time and again sociological research has revealed that mothers like Malaya, Vivian, Adrianna, and others we spoke with face many challenges raising children, and that the vast majority do everything they can to protect and nurture their children. The adverse conditions these mothers and their children find themselves in are created by inadequate and racist past and current social policies, yet mothers are told it is up to them alone to remedy them, to be superstrong. This is a losing proposition that puts undue pressure on low-income Black mothers and blames them when their children falter.

Stereotypes of poor Black women as bad mothers mean that they are more heavily monitored by the state and their mothering is treated with suspicion, even by their kids’ teachers

As for Toya Graham, six months after she was filmed determinedly trying to keep her son from joining the Baltimore protests against police brutality, Graham described her life to a CBS reporter as a constant struggle. Speaking of her 16-year-old son, Graham said, “I know there’s nothing out there but harm. But I’m going to protect him…I know a lot of mothers out here understand where I’m coming from. We’re struggling, we’re just trying to make sure we keep food on our table for our children, keep them out harm’s way, keep them out of danger.” On being dubbed a hero, Graham responded, “I just don’t feel like a hero. This is a real struggle. When the cameras is gone, the reality of life is still there. It’s still there.”

Sybrina Fulton, Samira Rice, and Leslie McSpadden, the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, and Michael Brown, respectively, at the National March on Washington for Justice in 2014.

Baltimore saw days of unrest following Freddie Gray’s death in police custody.

The everyday decisions Black mothers make for their kids are scrutinized.

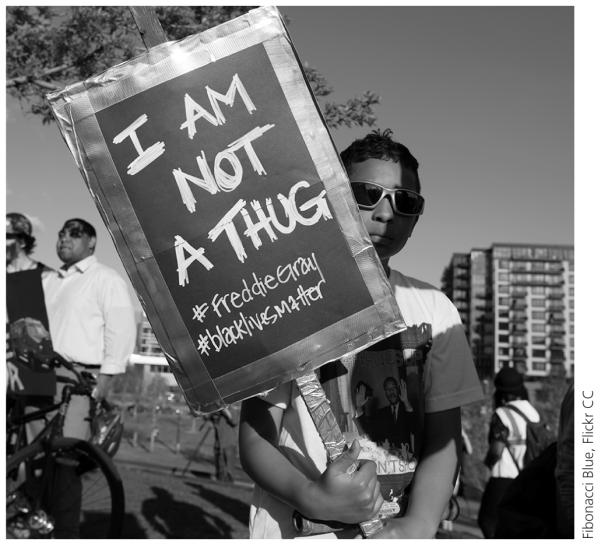

At a Minneapolis march in solidarity with the people of Baltimore, April 2015.

Contributor Information

Sinikka Elliott, Department of sociology and anthropology at North Carolina State University.

Megan Reid, University of Wisconsin’s Institute for Research on Poverty.

Recommended Readings

- Charlton TF. The Good Mother Myth. Seal Press; New York: 2013. The Impossibility of the Good Black Mother. Explores the negative stereotypes that Black mothers face in their everyday lives through a combination of personal essay and gender and race theory. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; New York: 2000. Explores the uniqueness of Black women’s perspectives and develops an accessible critical social theory. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson Ann Arnett. Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor: 2000. Offers a rich account of students’ and teachers’ daily interactions to demonstrate the ways racialized gender stereotypes lead schools to disproportionately punish Black boys. [Google Scholar]

- Levine Judith. Ain’t No Trust: How Bosses, Boyfriends, and Bureaucrats Fail Low-Income Mothers and Why It Matters. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2013. Documents low-income women’s interactions with untrustworthy actors and how they contribute to further lack of trust. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts Dorothy. Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare. Basic Civitas Books; New York: 2002. Examines the racist underpinnings of the child welfare system and the consequences for Black families and communities. [Google Scholar]