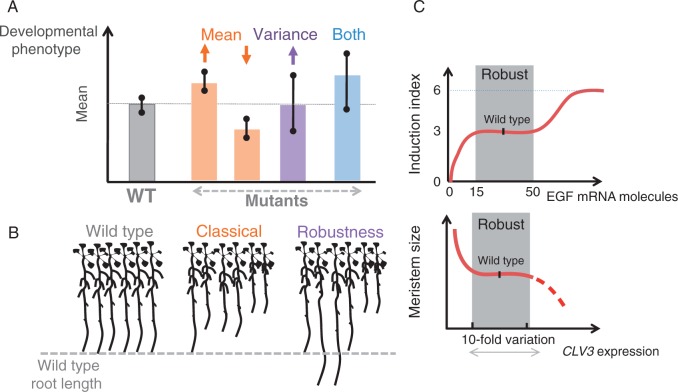

Fig. 2.

Defining robustness genes and robustness to gene expression change. (A) For any quantifiable phenotype, classical developmental mutants are defined herein as those displacing the mean, leading to either an increased or decreased mean, whereas robustness mutants as those increasing the phenotypic variance without much effect on the mean. In practice, the most common case is mutants that do both at the same time sensu Waddington. (B) An example showing a strict robustness defect using root length as the phenotype of interest. (C) Examples illustrating the effect of changing gene expression levels on two different developmental phenotypes: the nematodes’ vulval cell fate induction (upper panel) in response to EGF expression (presented by the number of mRNA molecules quantified in situ) showing that the induction index tolerates a change in expression ranging from 15 to 50 mRNA molecules (Barkoulas et al., 2013). Exposure to <15 mRNA molecules causes hypoinduction, whereas expression of >50 mRNA molecules causes hyperinduction. The lower panel illustrates the example of plant meristem size in response to change in expression level of CLAVATA3 (CLV3) relative to the wild type (100 %). Meristem size is shown to tolerate a ten-fold variation in CLV3 expression (from 33 % to 320 % that of the wild type) (Muller et al., 2006).