Abstract

Oxidative allene amination provides rapid access to densely functionalized amine-containing stereotriads through highly reactive bicyclic methyleneaziridine intermediates. This strategy has been demonstrated as a viable approach for the construction of the densely functionalized aminocyclitol core of jogyamycin, a natural product with potent antiprotozoal activity. Importantly, the flexibility of oxidative allene amination will enable the syntheses of modified aminocyclitol analogues of the jogyamycin core.

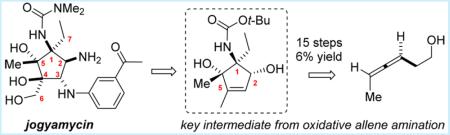

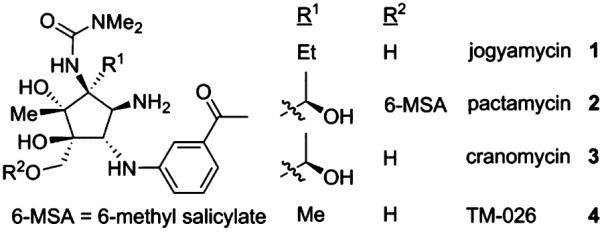

Jogyamycin (1) was first isolated in 2012 from a culture broth of Streptomyces sp. a-WM-JG-16.2, joining a family of aminocyclopentitols that include pactamycin (2), cranomycin (3), and TM-026 (4) (Figure 1).1 Jogyamycin itself exhibits potent antiprotozoal activity against important diseases including malaria and African sleeping sickness, while pactamycin and analogs have been shown to possess anticancer, antiviral, and antimicrobial activity in addition to antiprotozoal activity.1,2 Crystal structures of pactamycin with the ribosomal 30S subunit indicate it acts as a universal inhibitor of translocation in a highly conserved region of the ribosome, explaining the wide range of biological activity exhibited by this family of molecules.3 Subtle structural changes in the aminocyclitol motif have been shown to alter the activity of these natural products significantly.2d–g Further exploration of the structure–activity relationship of this family of molecules may help attenuate the cytotoxicity that these compounds possess.

Figure 1.

Biologically active aminocyclitol natural products.

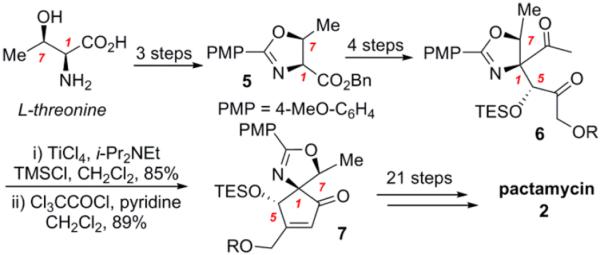

In addition to their potent biological activity, jogyamycin and its analogs pose a significant synthetic challenge that has drawn the interest of a number of research groups.4 All members of this class of compounds exhibit a fully substituted cyclopentane ring system with a heteroatom present on each carbon. Three contiguous quaternary carbons, as well as the dense functionalization around the ring that includes sensitive urea and aniline moieties, have inspired various strategies to achieve the syntheses of these challenging motifs.4 Pactamycin was the first molecule in this family to yield to total synthesis, as reported by Hanessian and co-workers in 2011 (Scheme 1).4a This landmark synthesis converted l-threonine into the oxazoline 5 to set the C-7 stereocenter. This stereochemical information was parlayed to the C-1 stereocenter through an aldol reaction, yielding 6 after a short sequence of steps. A series of functional group interconversions and a Ti-mediated aldol reaction/condensation led to the formation of 7, which was eventually transformed to 2 in 21 subsequent steps.

Scheme 1.

Hanessian's Approach to Pactamycin

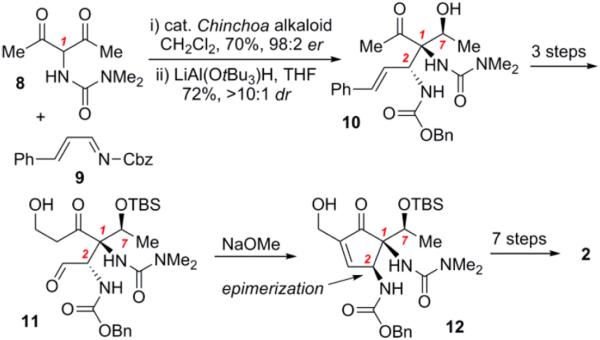

The most recent synthesis of pactamycin was completed by the Johnson group in 2013 (Scheme 2).4b This fundamentally different strategy first sets the C-2 stereocenter via an asymmetric Mannich reaction between 8 and 9, albeit with the incorrect configuration. Stereochemistry at the urea-bearing C-1, as well as at C-7, was set using a desymmetrizing β-diketone monoreduction to yield 10. Intramolecular aldol condensation/selective epimerization of 11 delivered 12 with the correct C-2 stereochemistry, which was then carried on to 2 in 7 steps.

Scheme 2.

Johnson's Approach to Pactamycin

Two similarities between the Hanessian and Johnson syntheses are the intramolecular aldol condensations to close the cyclopentene rings and the use of the exocyclic C-7 stereocenter as the linchpin of the synthetic strategy. Hanessian used C-7 to set the important C-1 stereocenter that, in turn, was employed to set all subsequent stereocenters in the synthesis.

Johnson also engaged the C-7 stereocenter to set the correct stereochemistry at C-1 and used both C-1 and C-7 to “correct” the C-2 stereochemistry. This strategic use of the C-7 stereocenter proved vital to both Johnson and Hanessian's work.

In contrast to pactamycin, both jogyamycin 1 and 4 lack a C-7 stereocenter. It has been shown that the subtle changes of the C-1 side chain have a significant effect on the biological activity.2c,g Furthermore, attempts by Johnson and co-workers to cleave the alcohol at C-7 during studies directed toward analogue synthesis were unsuccessful.2f Therefore, we felt that it would be useful to develop a synthesis of 1 that could accommodate flexibility in the oxidation state at C-7. We also wanted to develop a strategy that would eventually be capable of delivering access to a broad range of jogyamycin analogues where the positioning, identity, and stereochemistry of heteroatoms in the cyclopentane core could be controlled at will. Finally, developing a potentially asymmetric synthesis of 1 would be an interesting challenge in the absence of the diastereocontrol provided by the handle at C-7.4b

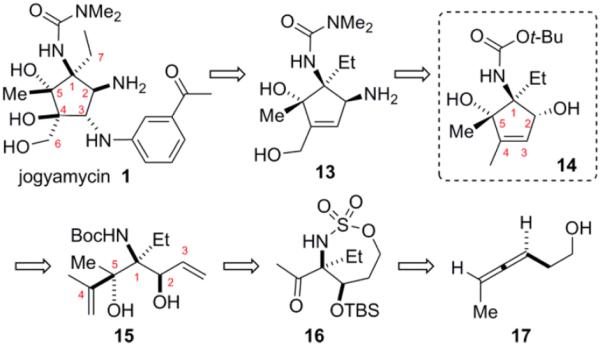

With these goals in mind, we proposed to apply our recently developed oxidative allene amination method to the construction of the cyclopentitol core of jogyamycin.5 The retrosynthetic analysis is shown in Scheme 3. Moving from 1 to 13, we envisaged that the alcohol at C-4 and the aniline at C-3 could arise through an epoxidation/epoxide opening sequence of 13. The exocyclic alcohol could be installed via a selective allylic C–H oxidation and the amine at C-2 from a functional group interconversion of the 2° alcohol in the key target 14. The cyclopentene ring of 14 would arise from a ring-closing metathesis of the diene 15. The relative stereochemistry at C-5 was predicted to be set through an addition of isopropenyl-magnesium bromide to the carbonyl of 16 through chelation control. The olefin at C-3 of 15 could be formed through a sulfamate cleavage/elimination sequence of 16. Amino ketone 16 would arise from the allene 17 through an enesulfamate intermediate, as described in more detail in Scheme 4.

Scheme 3.

Proposed Retrosynthetic Approach towards the Jogyamycin Core Using Oxidative Allene Amination

Scheme 4.

Oxidative Allene Amination for the Synthesis of Densely Functionalized Amine Triads

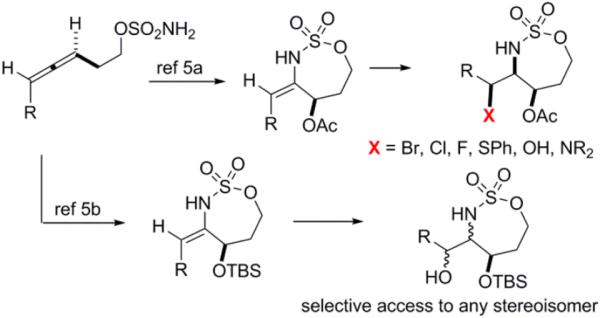

Previous work in our group has shown that allene aziridination yields enesulfamate intermediates that serve as tunable and versatile scaffolds for further functionalization (Scheme 4).5 By using different electrophiles, the installation of various heteroatoms at the three original allene carbons can be accomplished in a stereodefined manner in two steps. In addition to heteroatom diversity, our methods provide stereochemical diversity, as illustrated by work showing all four O/N/O triads are accessible from a single allene precursor.5b Effective transfer of the axial chirality of the allene to the triad enables the syntheses of enantiomerically enriched amine products. This flexibility indicated oxidative allene amination would be an ideal vehicle for not only the synthesis of 1, but more importantly, functionally and stereochemically diverse analogues of 1 that could be employed for SAR studies of jogyamycin.

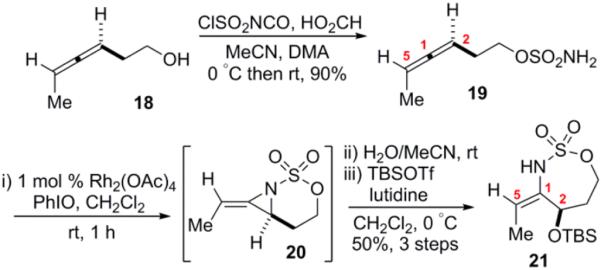

The substrate homoallenic sulfamate 19 was synthesized in one step from commercially available homoallenic alcohol 18 (Scheme 5).6 Rh-catalyzed intramolecular aziridination of 19 is observed exclusively at the proximal double bond of the allene in a > 20:1 E/Z ratio; no aziridination of the distal bond occurs. Due to its relative instability, 20 is not isolated but is subjected to ring opening with water following a quick solvent exchange. The crude alcohol is then protected with a TBS group prior to isolation to furnish the enesulfamate 21 in good yield over the three steps with just a single purification step. This reaction sequence has been performed several times on scales up to 8 g with consistent yields obtained.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of the Key Enesulfamate 21

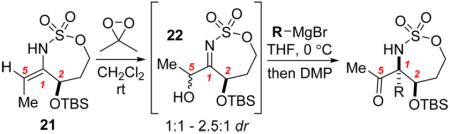

With significant quantities of 21 in hand, the next goal was to develop conditions for setting the important C-1 stereocenter. Epoxidation of 21, followed by immediate rearrangement, yielded the imino alcohol 22 in near-quantitative yields but with low dr (Table 1). While the stereocenter at C-5 appeared to be of little importance, as it is later destroyed via oxidation to a ketone, this low dr could be transferred to the C-1 stereocenter if chelation control operates in the addition of the organometallic reagent to the imine of 22, which was observed in prior studies. Changing the temperature had little effect on the dr of 22; the greatest effect on dr seemed to be the age of the DMDO solution, with older solutions giving decreased dr. To complicate the situation, low yields were generally observed when EtMgBr was used as the nucleophile for addition to 22, as significant competing hydride reduction was observed (Table 1, entry 1). Addition of anhydrous CeCl3 or LaCl3–2LiCl to the EtMgBr did not yield any improvements.7 Reaction of vinylmagnesium bromide or ethynylmagnesium bromide with 22 gave slightly better yields, but the selectivity of the organometallic addition still mirrored that of the DMDO oxidation (entries 2, 3). However, cooling the ethynylmagnesium bromide solution at 0°C for approximately 30 to 60 min prior to addition of 22 resulted in both higher yields and significantly improved dr (entry 4). This cooling protocol resulted in the formation of considerable amounts of precipitate, leading to the hypothesis that perturbation of the Schlenk equilibrium yields formation of higher-order species that increase the propensity for attack opposite the bulky –OTBS group, irrespective of the C-5 stereocenter.4c,5b,8 Addition of acetylides to similar imines has previously proven to be a viable strategy for introducing new functionality that can later be manipulated into the desired functional groups.9 The stereochemical relationship between C-1 and C-2 of 24 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (see the Supporting Information (SI) for further details).

Table 1.

| entry | R | product | yield | dr a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | Et | 16 | 29%c | 1.9:1 |

| 2 | CH=CH2 | 23 | 45% | 2:1 |

| 3 | C≡CH | 24 | 48% | 2.3:1 |

| 4d | C≡CH | 24 | 68% | 11.5:1 |

Based on 1H NMR analysis of crude product.

Reaction using CH2Cl2 as the solvent.

Isolated yield and dr are before DMP oxidation. Hydride reduction was a significant byproduct observed in 18% yield.

Grignard prestirred at 0 °C for 1 h prior to addition. Yield refers to isolated material.

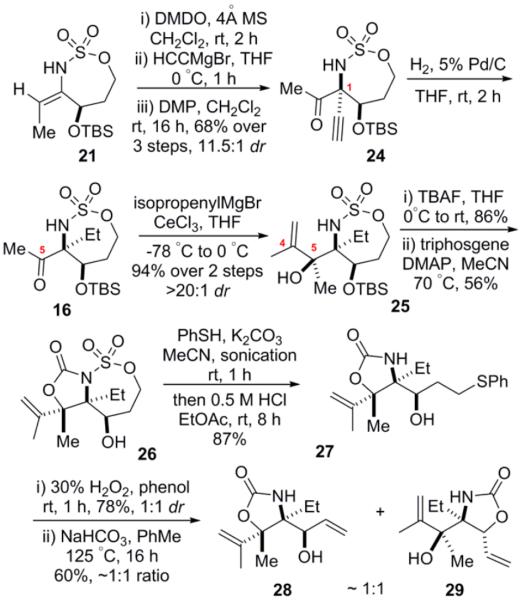

Having set the C-1 stereocenter, the alkyne was reduced to form 16 (Scheme 6). Reaction of the carbonyl of 16 with isopropenyl MgBr in the presence of CeCl3 occurred through chelation control to deliver 25 and set the C-5 stereocenter; isopropenyl MgBr alone gave only recovered starting material, likely due to enolization of the sterically encumbered ketone outcompeting the desired nucleophilic addition.7a The product 25 was isolated as a single diastereomer in high yield over the two steps. The relative stereochemical relationships between C1–C2–C5 in 25 were confirmed by X-ray crystallography (see the SI for further details).

Scheme 6.

First Attempted Route to the Key Core 14

Next, we set about activating the nitrogen of 25 by installing an electron-withdrawing group to render the sulfamate susceptible to nucleophilic ring opening. Unfortunately, the sulfamate nitrogen of 25 proved resistant to further functionalization using a variety of electrophiles, likely due to the large steric bulk around the nitrogen coupled with its weak nucleophilic character. As this strategy was unsuccessful, attempts to alleviate some of the steric bulk by removing the TBS group were carried out. Although subsequent reaction of the nitrogen still proved difficult, the oxazolidinone 26 could be formed using forcing conditions with triphosgene. With the nitrogen sufficiently activated, the sulfamate of 26 could be cleaved using thiophenol as a pro-nucleophile, followed by extended stirring with aqueous HCl to liberate SO3 and yield 27.10 Selective oxidation to the sulfoxide, followed by thermolysis, yielded 28 and 29 as approximately a 1:1 mixture.11 Unfortunately, all attempts to cleave the oxazolidinone were unsuccessful, as were attempts to carry out ring closing metathesis.

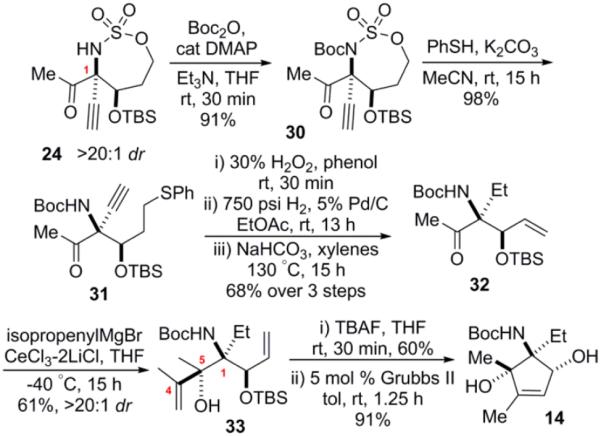

Due to the inability to cleave the oxazolidinone in 28 and 29, we opted to avoid such intermediates by attempting to functionalize the less hindered nitrogen prior to addition of the isopropenyl group. The isopropenyl subunit could later be installed after cleavage of the sulfamate. Unfortunately, all attempts to functionalize the nitrogen of 16 led to recovered starting material. Attempts to install the urea directly on 24, using dimethylcarbamoyl chloride or methyl isocyanate, led to either recovered starting material or complex mixtures of products. However, reaction of 24 with Boc2O yielded 30 in high yield (Scheme 7). Attempts to hydrogenate 30 to the alkane yielded 16 (see Scheme 6), presumably due to the increased sterics posed by the ethyl group as compared to the alkyne. To circumvent this issue, 30 was reacted directly with thiophenol to yield 31 in near-quantitative yield. Oxidation to the sulfoxide permitted reduction of the alkyne under high pressures of H2 which, after thermolysis, yielded 32 in good yield. Addition of the isopropenyl subunit to C-5 of 32 to deliver 33 initially proved more difficult than anticipated due to oxazolidinone formation with the tertiary alkoxide resulting from nucleophilic addition to the ketone. Ultimately, we found that performing the addition in the presence of CeCl3–2LiCl at −40 °C slowed down the attack of the resulting alkoxide on the Boc group such that diene 33 could be isolated as the major product in >20:1 dr.7b Desilylation of 33, followed by ring closing metathesis using the Grubbs II catalyst, delivered 14 in excellent yield. The configuration of the C-5 stereocenter was confirmed by 1D nOesy analysis, indicating that the organometallic addition to 32 proceeds through chelation control, where the C-5 stereochemistry is dictated by the configuration at C-1.

Scheme 7.

Successful Route to the Key Core Structure 14

In conclusion, we have established a reliable route to a densely functionalized cyclopentene motif 14 which maps onto the core of jogyamycin. The challenging C-5 and C-1 quaternary stereocenters are set at an early stage using oxidative allene aziridination as a key step. Employing this approach allows deoxygenation to be achieved at C-7 of jogyamycin, which has proven challenging using reported routes to pactamycin. Another nice feature of this strategy is our anticipated ability to utilize different allene substrates, easily install diverse nucleophiles at either the C1 or C-2 stereocenters, introduce different side chains at C5, and manipulate oxidation of the alkene of the cyclopentene core to enable the versatile syntheses of novel analogues. Work to complete the synthesis of jogyamycin is currently underway and is focused on amination at the C-2 position, oxidation of the C-6 position, and establishment of the C-3 and C-4 stereocenters. The beautiful work carried out in the total syntheses of pactamycin will aid us in this endeavor.4a–c

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lu Liu and Dr. Charles Fry, both at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, for assistance with NMR studies. This work was funded by NIH 1R01GM111412-01. J.M.S. is an Alfred P. Sloan Fellow. The NMR facilities at UW—Madison are funded by the NSF (CHE-9208463, CHE-9629688) and NIH (RR08389-01).

Footnotes

Supporting Information The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03453.

Experimental procedures and characterization for all new compounds (PDF)

NMR spectra (PDF)

Crystallographic data for 24 (CIF)

Crystallographic data for a derivative of 25 (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Iwatsuki M, Nishihara-Tsukashima A, Ishiyama A, Namatame M, Watanabe Y, Handasah S, Pranamuda H, Marwoto B, Matsumoto A, Takahashi Y, Otoguro K, Ōmura S. J. Antibiot. 2012;65:169. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) White FR. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports. 1962;24:75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito T, Roongsawang N, Shirasaka N, Lu W, Flatt PM, Kasanah N, Miranda C, Mahmud T. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2253. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lu W, Roongsawang N, Mahmud T. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:425. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Otoguro K, Iwatsuki M, Ishiyama A, Namatame M, Nishihara-Tukashima A, Shibahara S, Kondo S, Yamada H, Ōmura S. J. Antibiot. 2010;63:381. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hanessian S, Vakiti RR, Chattopadhyay AK, Dorich S, Lavallée C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1775. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sharpe RJ, Malinowski JT, Sorana F, Luft JC, Bowerman CJ, DeSimone JM, Johnson JS. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:1849. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Almabruk KH, Lu W, Li X, Abugreen M, Kelly JX, Mahmud T. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1678. doi: 10.1021/ol4004614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Egebjerg J, Garrett RA. Biochimie. 1991;73:1145. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90158-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carter AP, Clemons WM, Brodersen DE, Morgan-Warren RJ, Wimberly BT, Ramakrishnan V. Nature. 2000;407:340. doi: 10.1038/35030019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dinos G, Wilson DN, Teraoka Y, Szaflarski W, Fucini P, Kalpaxis D, Nierhaus KH. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:113. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tourigny DS, Fernández IS, Kelley AC, Vakiti RR, Chattopadhyay AK, Dorich S, Hanessian S, Ramakrishnan V. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:3907. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Hanessian S, Vakiti RR, Dorich S, Banerjee S, Lecomte F, DelValle JR, Zhang J, Deschênes-Simard B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:3497. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Malinowski JT, Sharpe RJ, Johnson JS. Science. 2013;340:180. doi: 10.1126/science.1234756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Malinowski JT, McCarver SJ, Johnson JS. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2878. doi: 10.1021/ol301140c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Loertscher BM, Young PR, Evans PR, Castle SL. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1930. doi: 10.1021/ol4005799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Haussener TJ, Looper RE. Org. Lett. 2012;14:3632. doi: 10.1021/ol301461e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Knapp S, Yu Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1359. doi: 10.1021/ol0702472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Tsujimoto T, Nishikawa T, Urabe D, Isobe M. Synlett. 2005;433 [Google Scholar]; (h) Hanessian S, Vakiti RR, Dorich S, Banerjee S, Deschênes-Simard B. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:9458. doi: 10.1021/jo301638z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Adams CS, Boralsky LA, Guzei IA, Schomaker JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10807. doi: 10.1021/ja304859w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Adams CS, Grigg RD, Schomaker JM. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:3046. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fiori KW, Espino CG, Brodsky BH, Du Bois J. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3042. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Imamoto T, Sugiura Y, Takiyama N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4233. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krasovskiy A, Kopp F, Knochel P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:497. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Xia A, Heeg MJ, Winter CH. Organometallics. 2003;22:1793. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Fleming JJ, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3926. doi: 10.1021/ja0608545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kenworthy MN, Taylor RJ. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:603. doi: 10.1039/b416477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Xu WL, Li YZ, Zhang QS, Zhu HS. Synthesis. 2004;2:227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.