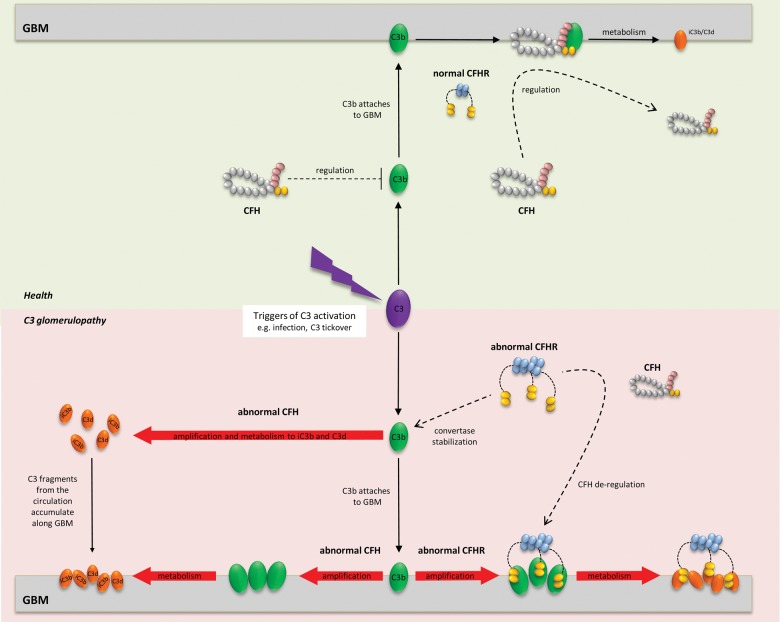

FIGURE 4:

Schematic representation of pathogenesis of C3 glomerulopathy. Triggers of C3 activation (depicted at the centre) may be exogenous (e.g. infection) or endogenous (C3 tickover). C3 activation generates C3b molecules for attachment to surfaces including the GBM. In health (upper panel), C3b amplification is tightly controlled by factor H (CFH) in the circulation. Thus minimal C3b becomes available for attachment to surfaces, where amplification is further regulated by CFH on the GBM. In theory, any surface-attached C3b is then metabolised, leaving C3 fragments (iC3b, C3d) attached to the GBM, and releasing CFH back into the circulation. In practice, neither C3 nor CFH are detected along the GBM in normal glomeruli. In the setting of abnormal CFH (bottom left panel), uncontrolled C3 activation leads to excessive C3 fragments (iC3b, C3d) in the circulation, which later accumulate along the GBM. Some C3b amplification/metabolism may also occur on the GBM. Enhanced CFH de-regulation due to abnormal CFHR proteins (bottom right panel) has been proposed as one mechanism by which C3 accumulates along the GBM despite intact CFH. Competitive inhibition of CFH by abnormal CFHR proteins along the GBM would facilitate C3b surface amplification/metabolism. Increased C3b amplification in plasma due to an abnormal CFHR protein that stabilizes the C3 convertase has also been demonstrated (see the text).