Abstract

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) is a sensitive technique used in gene expression studies. To achieve a reliable quantification of transcripts, appropriate reference genes are required for comparison of transcripts in different samples. However, few reference genes are available for non-model taxa, and to date, reliable reference genes in Cycas elongata have not been well characterized. In this study, 13 reference genes (ACT7, TUB, UBQ, EIF4, EF1, CLATHRIN1, PP2A, RPB2, GAPC2, TIP41, MAPK, SAMDC and CYP) were chosen from the transcriptome database of C. elongata, and these genes were evaluated in 8 different organ samples. Three software programs, NormFinder, GeNorm and BestKeeper, were used to validate the stability of the potential reference genes. Results obtained from these three programs suggested that CeGAPC2 and CeRPB2 are the most stable reference genes, while CeACT7 is the least stable one among the 13 tested genes. Further confirmation of the identified reference genes was established by the relative expression of AGAMOUSE gene of C. elongata (CeAG). While our stable reference genes generated consistent expression patterns in eight tissues, we note that our results indicate that an inappropriate reference gene might cause erroneous results. Our systematic analysis for stable reference genes of C. elongata facilitates further gene expression studies and functional analyses of this species.

Introduction

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) has been a key technology of gene expression analysis in numerous molecular biology applications [1]. With high throughput capability for quantification of transcript levels, qRT-PCR is considered highly sensitive, accurate, and reproducible [2]. However, some variables such as the integrity, amount and purity of the RNA, as well as enzyme efficiency during cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification make it necessary to normalize the data for an accurate and reliable result [3]. Thus, a reliable reference gene in which expression is constant and stable at different developmental stages, nutritional conditions or experimental conditions is required for normalization [4]. Common reference genes or internal control genes used in qRT-PCR are housekeeping genes (HKGs) related to cell maintenance, such as actin (ACT), tubulin (TUB), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 18S ribosomal RNA (18S), ubiquitin (UBQ) and elongation factor 1-α (EF 1-α) [5–7]. New reference genes have been studied in model and non-model plants, such as Arabidopsis [7], African oil palm [8] and Brazilian pine [5]. However, a comprehensive genome sequence of Cycas elongata is not yet available since identification of internal control genes is time consuming and specialized work. Therefore, the selection of reference genes for qRT-PCR has not yet been reported in C. elongata.

In the last two decades, progress has been made in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of floral developmental control in angiosperms [9]. Development of eudicot flowers is controlled by MADS box genes in a well-known ABCDE model [10]. However, it is still largely unclear how the flower originated during evolution [11–13]. In a comprehensive framework of evolutionary developmental biology (‘evo-devo’), the origin and evolution of the gene controlling floral organ specification is intimately intermingled with the evolutionary origin and diversification of the angiosperm flower [14]. To better understand the origin of the flower, it is inevitable to study gymnosperms, the closest extant relatives of the angiosperms. Extant gymnosperms comprise conifers, gnetophytes, Ginkgo and cycads. Only one survey of cycads regarding the MADS-box gene [15] has been described, wheras several studies about MADS-box genes of conifers, gnetophytes and Ginkgo have been reported [13, 14, 16]. Thus, it is necessary to select stable reference genes of cycads for further molecular studies.

In this current study, thirteen candidate reference genes were evaluated in eight plant tissues (megasporophyll, microsporophyll, ovules, roots, stalks, female plant leaves, male plant leaves and asexual plant leaves). Based on the transcriptome data of C. elongata (unpublished), the thirteen candidate reference genes were first identified by their orthologous genes in model plants, then cloned, sequenced and confirmed. To validate our results, we used the most stable reference genes to assess the expression levels of CeAG gene in the eight plant tissues.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

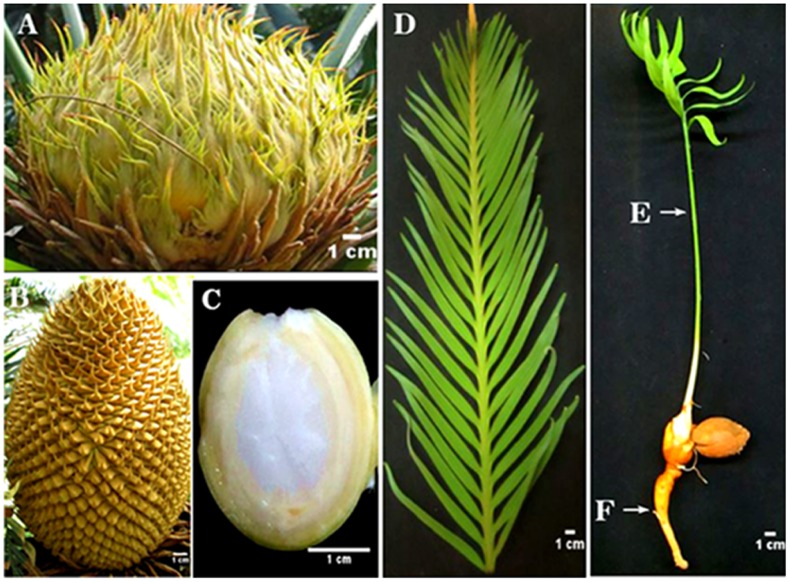

Reproductive and vegetative tissues were obtained from the female, male and asexual C. elongata plants growing in Cycads Conservation Center in the Fairylake Botanical Garden. The megasporophyll, microsporophyll, ovule and leaves of female plants, male plants and asexual plants were harvested from C. elongate specimens that were approximately twenty years old (Fig 1A, 1B, 1C and 1D). The root and stalk were collected from seedlings (Fig 1E and 1F) and washed through with deionized water, and then subjected to a one minute sterilization with 75% alcohol. Each type of harvested tissues were divided in two biological replicates and all of them were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until needed.

Fig 1. C. elongata tissues and organ sample set.

(A) Megasporophyll; (B) Microsporophyll; (C) Ovule; (D) Leaf; (E) Stalk; (F) Root. Scale bars = 1 cm.

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

One gram of frozen tissue samples were grounded to fine powder with mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen. To extract total RNA we used a Magen HiPure Plant RNA Kit (http://www.magentec.com.cn/products.php?ID=504) per the manufacturer’s instructions. We determined concentration, purity, and integrity of the RNA samples using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (TU-1810, PGENERAL, China) and visualized via gel electrophoresis (2% agarose) (S1 Fig). The samples with 260/280 nm and 260/230 nm ratios between 1.9–2.5 and 1.9–2.2 (S2 Table), were considered for use in subsequent analyses. We used 2 μg of RNA for each sample used in genomic DNA elimination and reverse-transcription in order to acquire cDNA for RT-PCR. These processes were accomplished with the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Inc). The cDNA solution was diluted 20 times with EASY Dilution (TaKaRa, Inc) and aliquots were stored at -20°C until qRT-PCR.

Candidate gene selection, PCR primer design and candidate gene cloning and multiple sequences alignments

We selected thirteen candidate reference genes based on previous studies [17, 18]. The BLAST program (E < 1e-10) was employed to survey the C. elongata transcriptome databases using the corresponding Arabidopsis thaliana protein sequences as query sequences (Table 1). We designed primers using the Primer Premier 5 program (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/index.html), and designed the primers to flank the conserved domains determined by an NCBI conserved domain search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). The target amplified fragments were excised from electrophoresis gel and purified with HiPure Gel Pure DNA Kits (Magen, China) and subcloned into the pEASY®-T1 Simple Cloning vector (the pEASY®-T1 Simple Cloning Vector Kit from TRANSGEN BIOTECH, China) following the guidance provided by the manufacturer. Plasmids were transferred into Trans1-T1 Phage Resistant Chemically competent cells (TRANSGEN BIOTECH, China) and recombinant colonies were sequenced by Life Technologies Company. The nucleotide sequences were analyzed by BLAST [19] against NCBI non redundant sequences (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Table 1. Candidate reference genes, annotated functions, and primers used to amplify and their PCR parameters.

| Gene | A. thaliana Gene Description | A. Thaliana Ortholog | Primer sequences (5’ - 3’) forward/reverse | Tm (°C) | Amplicon length (bp) | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeCLATHRIN1 | clathrin adaptor complexes medium subunit family protein | NP_199475.1 | CTTCACCACTACTCCCAATG/CCTGATGTCTTCAAAAGGGA | 54 | 415 | 90 |

| CePP2A | serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP2A-1 catalytic subunit | NP_176192.1 | GTTATCAAGCGTGTCCAAAG/GAATGTGCAACCTGTGAAAT | 54 | 409 | 82 |

| CeRPB2 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB2 | NP_193902.1 | TCTTTTGCAGGTAAGACCTC/ACGAAGATTATGTGGACGAG | 52 | 1248 | 80 |

| CeGAPC2 | glyceraldehyde3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPC2 | NP_001077530.1 | GGCCATTCCAGTCAATTTTC/GTCATCCATGAAAGGTTTGG | 54 | 210 | 94 |

| CeTIP41 | TIP41-like protein tonoplast intrinsic protein4(Zea mays) | NP_195153.2 | AGACAGCTCTCTTGAACTTG/TGAAATGCAAACCAGAATGG | 55 | 900 | 84 |

| CeMAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | NP_172492.1 | GTGATTCTCTTACAGGGGTC/TCATACGGTATCGTCTGTTC | 54 | 803 | 77 |

| CeSAMDC | S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase | NP_001154585.1 | AAACCTTAGAAGCCCACAAT/TGTGTTAAGTACACTCGTGG | 54 | 735 | 74 |

| CeEIF4 | eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-3 | NP_177417.1 | AACCTTCCGAGCTGTATTTT/TCCAGTCCTCCTTATCAACA | 52 | 849 | 84 |

| CeEF1 | elongation factor 1-alpha 2 | NP_563800.1 | CAGCGAATTTTGAGAAGTGG/GGAACTCATACGAAGTCAGA | 55 | 745 | 78 |

| CeACT7 | actin 7 | NP_196543.1 | GGAGGTGCTACAACCTTTAT/TGATGGAGTTACACACACTG | 53 | 531 | 99 |

| CeTUB | tubulin alpha-6 chain | NP_193232.1 | GTTGGCCTCTCAATATCCAA/AATCCCTCTTCAGACCTCAT | 55 | 731 | 80 |

| CeUBQ | ubiquitin 11 | NP_567286.1 | GACGGGAAAGACCATAACTT/TGTGAATATAAGCCAGCGAT | 52 | 400 | 81 |

| CeCYP | Cyclophilin peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP19-2 | NP_179709.1 | AAAATCCCAGGGTGTTCTTG/ATTTCACCGCTGTCTACAAT | 55 | 511 | 81 |

qRT-PCR primer design, quantitative real-time PCR and data acquisition

The primers for qRT-PCR were based on the the thirteen cloned C. elongata sequences and were designed using the Primer designing tool program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_LOC=BlastHome). The primers exhibited melting temperatures between 57 and 59°C, primer lengths of 18–24 bp, GC content of 45–55% and amplicon lengths between104 and 287 bp. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed using a CTX96 Touch™ System (BIO-RAD) machine under following conditions: 3 min at 95°C, 36 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C and 10 s at 72°C in 96 well plates. The qRT-PCR procedure concluded with a melt-curve ramping from 60 to 95°C for 20 min. The 20 μl reaction mixtures contained 4 μl of 20 fold diluted template, 2 μl of each amplification primer (10 μM), 10μl of iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (BIO-RAD) and 4 μl sterile nuclease free water. All qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in technical triplicate and a non-template control was also included for each primer pair. Confirmation of primer specificity was based on the dissociation curve. In addition to baseline and threshold cycles (Ct), correlation coefficients (R2 values) and amplification efficiencies (E) for each primer pair was automatically determined using the CFX Manager™ Software (BIO-RAD). We used five dilutions of cDNA samples from C. Elongata vegetative leaves to obtain the standard curve.

Analysis of gene expression stability

Three different types of Microsoft Excel-based software, geNorm [20], NormFinder [21] and BestKeeper [22], were used to evaluate the stability of reference gene expression. BestKeeper utilizes the method mean Ct values as input whereas geNorm and NormFinder convert Ct values using the formula: 2−ΔCt, where ΔCt = each corresponding Ct value—minimum Ct value.

Validation of reference genes

The transcription factor gene AGAMOUS (AG), belongs to the MADS-box genes involved in the reproductive organ development in Cycas edentata [15]. AG was used to measure and normalize the most and least stable reference genes based off the analysis of geNorm, NormFinder and BestKeeper outputs. The experimental procedure for target genes was the same used for the selection of the reference genes. Samples from the megasporophyll, microsporophyll, female plant leaf, male plant leaf, asexual plant leaf, root, stalk and ovule were used to evaluate the relative expression level of the target gene, calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and presented as fold changes [23].

Results

Identification and cloning of putative references genes in C. elongata

From the C. elongata transcriptome database, we retrieved thirteen putative reference genes using the sequences of A. thaliana orthologs as probes (Table 1). Since no C. elongata relevant genetic sequences information is available online, we cloned and sequenced the reference genes according to the selected sequences. Thirteen expected fragments of reference genes (sequences shown in S2 File) were successfully amplified with sizes ranging from 210 to 1248 bp (S2 Fig). Nucleotide similarity of C. elongata orthologs were confirmed by comparison to the [19] NCBI web site after sequencing. Our results showed that all expected fragments obtained from C. elongate have at least 74% similarity to those of A. thaliana, with CeACT7 exhibiting the highest similarity (99%) with the ortholog of Arabidopsis (Table 1).

Verification of primer specificity and efficiency

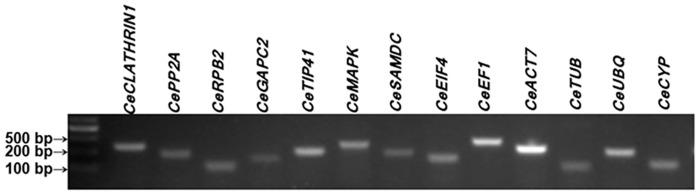

Primer specificity was assessed through a confirmatory PCR and 2% agarose gel electrophoresis which revealed expected single bands of desired lengths (Fig 2). Furthermore, the specificity of primer pairs in qRT-PCR was also confirmed from a single peak in all melting curves and an absence of peak in the no template control (NTC) (S3 Fig). PCR efficiency (E) was estimated from the standard curve varying from 94.6% for CeCYP to 106.4% for CeSAMDC (Table 2, S1 File), which conforms to the acceptable range of PCR efficiency 90–110% [24] and correlation coefficients (R2) ranged between 0.990–0.996. Taken together, the results indicate that the designed primers could accurately amplify the 13 candidate reference genes.

Fig 2. Agarose gel (2%) electrophoresis showing amplification of a specific qRT-PCR product of the expected size for each gene.

2000 bp DNA ladder marker was used.

Table 2. Candidate reference genes, specific qRT-PCR primers and different parameters derived from qRT-PCR analysis.

| Gene | Primer sequences (5’ - 3’) forward / reverse | Tm (°C) | Aplicon Length (bp) | Primer efficiency (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeCLATHRIN1 | CTTTTTGTTGGACGGGCTTT/AGGTGCTGTTGGTTGGCG | 58 | 237 | 98.9 | 0.991 |

| CePP2A | TGTCCAAAGATGGGGAGAGG/AGAGGGAATCATGAGAGCCG | 58 | 184 | 102.3 | 0.992 |

| CeRPB2 | CGAGAAAGCATCCGCACAA/AAGAAACGCCAGCCAAATAAA | 58 | 104 | 98 | 0.992 |

| CeGAPC2 | TCTGCCTCCTCGCCAATC/GCAAGCTGCACCACCAACT | 58 | 153 | 104.1 | 0.99 |

| CeTIP41 | ACACATTCACAACACCATACCGT/CAGCCAACTCATCTTCATACAAAA | 58 | 201 | 98.2 | 0.991 |

| CeMAPK | CATCCGTGAGAGCCTGAGAAGA/GCCCACAACACCGAAACCA | 58 | 253 | 105.4 | 0.99 |

| CeSAMDC | CCTCCCAACCTTCATTTTCA/TGCATCAGGCAATCTTCTTG | 56 | 193 | 106.4 | 0.99 |

| CeEIF4 | TCTCAGCTACCATGCCTCCT/CAGAGTGTGTCCAGCTTCCA | 57 | 157 | 96.6 | 0.995 |

| CeEF1 | ATCATTCTTCCTCCTCGTTC/AGTGTCTCTTCTCCGTTTCG | 57 | 287 | 97.4 | 0.996 |

| CeACT7 | GACATCTGAACCTTTCGGCA/GCTGGGCGTGACTTGACTGA | 59 | 232 | 100.6 | 0.994 |

| CeTUB | TGAGGCGAAGGATAAATGGTG/AATGCTGTTGGAGGCGGAACT | 59 | 112 | 101.7 | 0.996 |

| CeUBQ | AACTTTGGAGGTCGAGAGCA/GCCATCAACGAAGGTTCAAT | 59 | 213 | 94.6 | 0.991 |

| CeCYP | GCCCAAGGAGGGGACTTT/GCCCAAGGAGGGGACTTT | 58 | 129 | 94.6 | 0.995 |

Primer locations in the coding regions of corresponding genes

Expression profiling of reference genes

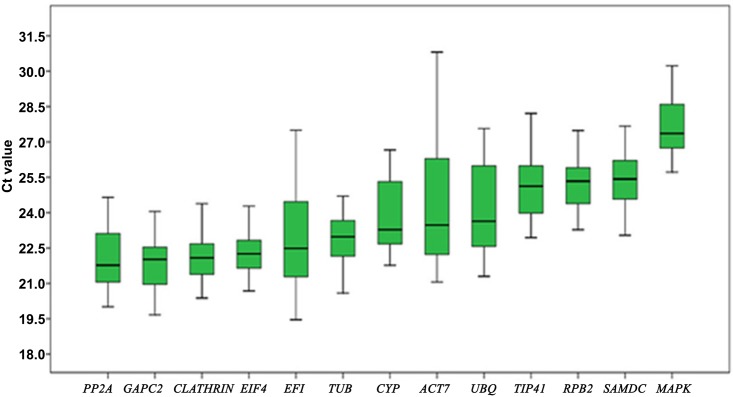

Analysis of the Ct values (S1 Table) for each gene showed variation in the expression levels across all samples. Based on the Ct value interquartile range (25–75% percentiles) for each reference gene, the median Ct values ranged from 22 to 28 cycles (Fig 3), with CePP2A (21.77) being the most abundantly expressed gene followed by CeGAPC2 (22.02), CeCLATHRIN1 (22.09), CeEIF4 (22.26), CeEF1 (22.49), CeTUB (22.98), CeCYP (23.28), CeACT7 (23.47), CeUBQ (23.64), CeTIP41 (25.12), CeRPB2 (25.34), CeSAMDC (25.43) and CeMAPK (27.36), the least expressed gene.

Fig 3. Box plot of the Ct value distribution of candidate reference genes in all C. elongata samples.

The box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values; the thin line within the box marks the median.

The lowest variation in gene expression was exhibited by CeEIF4, CeCLATHRIN, CeRPB2, CeTUB, CeGAPC2, CeSAMDC and CeMAPK with cycles below 2, while CeACT7 with cycles above 4 depicted the most variation, depicted by larger box and whisker taps for CeACT7 than for other genes (Fig 3).

geNorm analysis

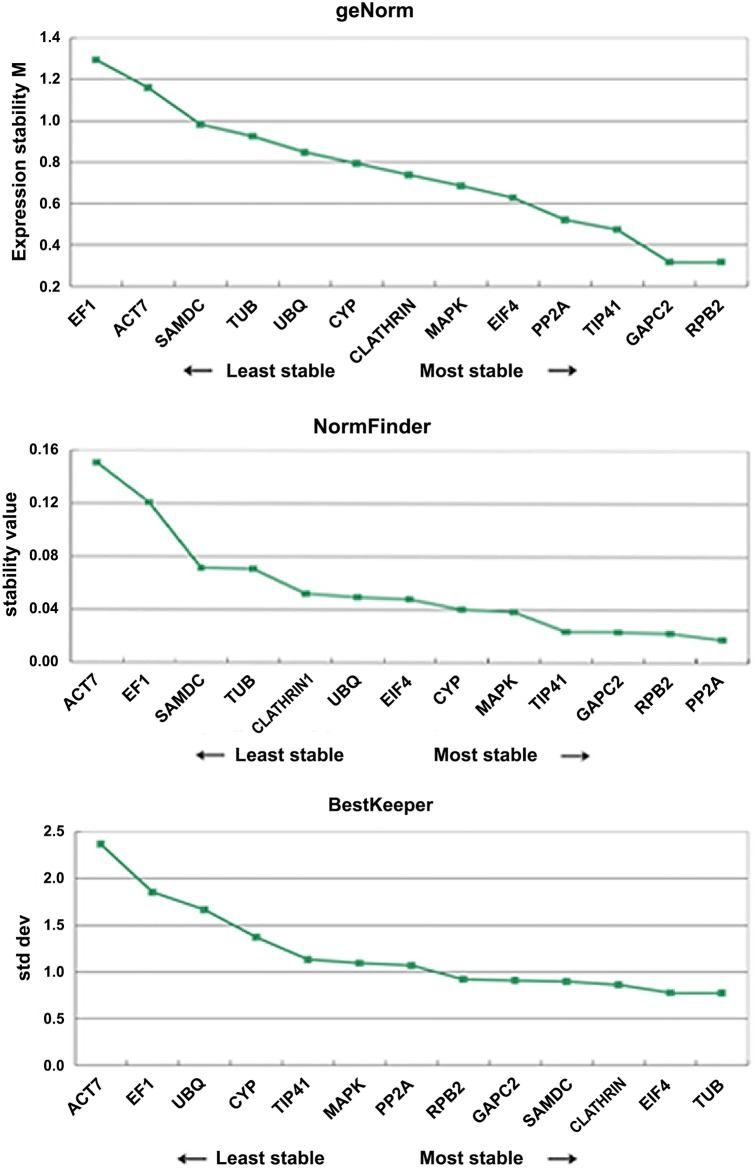

The program geNorm ranks reference genes based on the M value which is the mean pairwise expression ratio calculated from the average pairwise variation between a gene and all other control genes. It has been shown that M value and gene stability have a negative correlation [25]. geNorm recommends selecting reference genes with an M value below 1.5, which is supported by Vandesompele et al. who also suggest using M values lower than 1.0 to ensure the selection of the most stable gene[20]. Furthermore, M values below 0.5 indicate good stability of expression measure [25, 26]. In our analysis, 11 genes had M values below 1.0, and CeGAPC2 and CeRPB2 both had M values of 0.32, showing the highest expression stability, followed by CeTIP41 with 0.47, CePP2A with 0.52, CeEIF4 with 0.63 and CeMAPK with 0.69 (Fig 4, S3 Table). However, across all samples, CeACT7 and CeEF1, the traditional control genes, showed the lowest expression stability (M value up 1.0). For the three subsets, CeRPB2, CeGAPC2 and CeTIP41 are the most stable genes in reproductive tissues, vegetative tissues, and leaves tissues respectively as ranked by geNorm (Table 3).

Fig 4. Expression stability and ranking of the candidate reference genes calculated by geNorm, NormFinder and BestKeeper.

Ranking of 13 candidate reference genes (CLATHRIN1, PP2A, ACT7, RPB2, EF1, GAPC2, SAMDC, TIP41, MAPK, CYP, UBQ, EIF4 and TUB) calculated by geNorm, NormFinder and BestKeeper methods in all samples (megasporophyll, microsporophyll, leaves of female plant, male plant, and asexual plant, root, stalk and ovule).

Table 3. Ranking of candidate reference genes in three subsets of C. elongata samples based on geNorm.

| Reproductive tissues | Vegetative tissues | Leaves tissue | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm | geNorm | geNorm | |||

| Gene | M | Gene | M | Gene | M |

| RPB2 | 0.13 | GAPC2 | 0.38 | TIP41 | 0.22 |

| GAPC2 | 0.13 | RPB2 | 0.38 | RPB2 | 0.22 |

| EIF4 | 0.17 | TIP41 | 0.39 | GAPC2 | 0.29 |

| PP2A | 0.20 | CLATHRIN1 | 0.49 | CLATHRIN1 | 0.35 |

| CYP | 0.28 | PP2A | 0.56 | ACT7 | 0.40 |

| TUB | 0.36 | MAPK | 0.61 | CYP | 0.46 |

| TIP41 | 0.41 | EIF4 | 0.67 | MAPK | 0.52 |

| UBQ | 0.46 | UBQ | 0.75 | EIF4 | 0.56 |

| SAMDC | 0.51 | CYP | 0.82 | SAMDC | 0.61 |

| MAPK | 0.57 | TUB | 0.94 | PP2A | 0.66 |

| CLATHRIN1 | 0.67 | SAMDC | 1.03 | TUB | 0.71 |

| EF1 | 0.76 | ACT7 | 1.17 | UBQ | 0.79 |

| ACT7 | 0.93 | EF1 | 1.35 | EF1 | 0.88 |

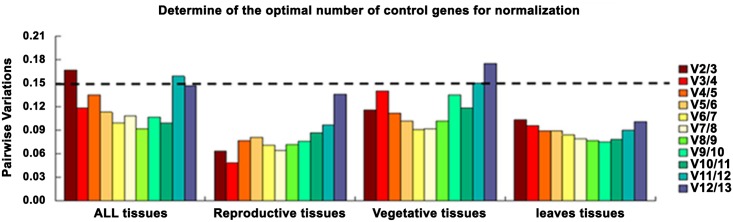

The optimal numbers of reference genes were calculated by pairwise variation (Vn/n+1) [20] for data normalization. A threshold of 0.15 was set as the cut-off value for V, below which no additional genes were included. A result of V3/4 < 0.15 indicated that the inclusion of a third reference gene (i.e. CeGAPC2, CeRPB2 and CeTIP41) was sufficient for an accurate normalization in total samples (Fig 5). When considering reproductive tissues (megasporophyll, microsporophyll and ovule), vegetative tissues (leaves of female plant, male plant and asexual plant, roots and stalks) and leaves tissues (leaves of female plant, male plant, and asexual plant) the calculated V2/3 was < 0.15 indicating that two reference genes would be useful for normalizing gene expression.

Fig 5. Pairwise variations (V) calculated by geNorm to determine the minimum number of reference genes for accurate normalization in four sets.

The cut off value is 0.15, below which the inclusion of an additional reference gene is not required. All tissues (megasporophyll, microsporophyll, leaves of female plant, male plant, and asexual plant, root, stalk and ovule). Reproductive tissues (megasporophyll, microsporophyll and ovule). Vegetative tissues (leaves of female plant, male plant, and asexual plant, root and stalk). Leaves tissues (leaves of female plant, male plant, and asexual plant).

NormFinder analysis

The NormFinder software can estimate the stability values of single candidate reference genes by calculating the intra-group and inter-group expression variability, with more stable gene expressions showing lower stability values. In total tissues, NormFinder ranked CePP2A, CeRPB2, CeGAPC2 and CeTIP41 among the six most stable reference genes, and CeACT7 and CeEF1 as the least stable control genes (Fig 4, S3 Table). The exception, CePP2A, was ranked fourth in gene stability by geNorm first by NormFinder. These discrepancies could be explained due to inter-group expression variations detected by NormFinder analysis, which is not taken into account by the geNorm algorithm [27].

BestKeeper analysis

BestKeeper ranks reference genes based on the standard deviation (SD) and the coefficient of variation of their Ct values, where lower SD of Ct values indicate less variable expression compared to higher SD values. Genes with SD greater than 1.0 are considered unstable and should be avoided. CeTUB, CeEIF4, CeCLATHRIN1, CeSAMDC, CeGAPC2 and CeRPB2 (SD of 0.77, 0.78, 0.86, 0.90, 0.91 and 0.92 respectively) possessed SD values below 1.0, indicating low variation in gene expression, while CeACT7 with SD of 2.48 and CeEF1 with SD of 2.31 were the most variable in expression across all samples (Fig 4, Table 4). BestKeeper ranked CeGAPC2 and CeRPB2 as acceptable reference genes, corroborating the results from geNorm and NormFinder.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics and expression level obtained from BestKeeper.

| CLATHRIN1 | PP2A | ACT7 | RPB2 | EF1 | GAPC2 | SAMDC | TIP41 | MAPK | CYP | UBQ | EIF4 | TUB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| GM [CP] | 22.03 | 22.03 | 24.28 | 25.18 | 22.85 | 21.73 | 25.41 | 24.99 | 27.58 | 23.82 | 24.05 | 22.26 | 22.87 |

| AM [CP] | 22.06 | 22.07 | 24.43 | 25.21 | 22.95 | 21.76 | 25.44 | 25.03 | 27.61 | 23.87 | 24.12 | 22.28 | 22.89 |

| Min [CP] | 20.38 | 20.01 | 21.06 | 23.28 | 19.46 | 19.67 | 23.04 | 22.94 | 25.72 | 21.77 | 21.30 | 20.68 | 20.59 |

| Max [CP] | 24.38 | 24.65 | 30.81 | 27.48 | 27.50 | 24.05 | 27.67 | 28.21 | 30.23 | 26.66 | 27.57 | 24.28 | 24.70 |

| SD [± CP] | 0.86 | 1.07 | 2.37 | 0.92 | 1.85 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.37 | 1.67 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| CV [% CP] | 3.90 | 4.84 | 9.69 | 3.65 | 8.08 | 4.16 | 3.52 | 4.52 | 3.96 | 5.75 | 6.91 | 3.48 | 3.38 |

| Min [x-fold] | -3.15 | -4.06 | -9.30 | -3.74 | -10.47 | -4.18 | -5.18 | -4.14 | -3.62 | -4.14 | -6.73 | -3.00 | -4.87 |

| Max [x-fold] | 5.09 | 6.14 | 92.61 | 4.91 | 25.14 | 4.99 | 4.78 | 9.33 | 6.30 | 7.16 | 11.47 | 4.05 | 3.55 |

| SD [± x-fold] | 1.82 | 2.10 | 5.16 | 1.89 | 3.62 | 1.87 | 1.86 | 2.19 | 2.13 | 2.59 | 3.17 | 1.71 | 1.71 |

N: number of samples; CP: crossing point; GM [CP]: geometric CP mean; AM [CP]:arithmetic CP mean; Min [CP] and Max [CP]: CP threshold values; SD [±CP]: CP standard deviation; CV [%CP]: variance coefficient expressed as percentage of CP level; Min [x-fold] and Max [x-fold]: threshold expression levels expressed as absolute x-fold over- or under-regulation coefficient; SD [±x-fold]: standard deviation of absolute regulation coefficient. SD and CV are indicated in bold.

Validation of reference genes

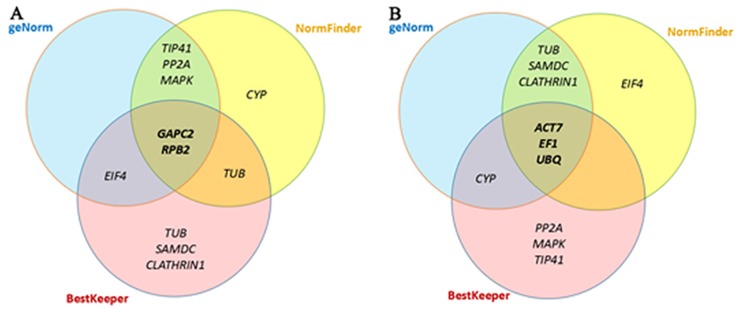

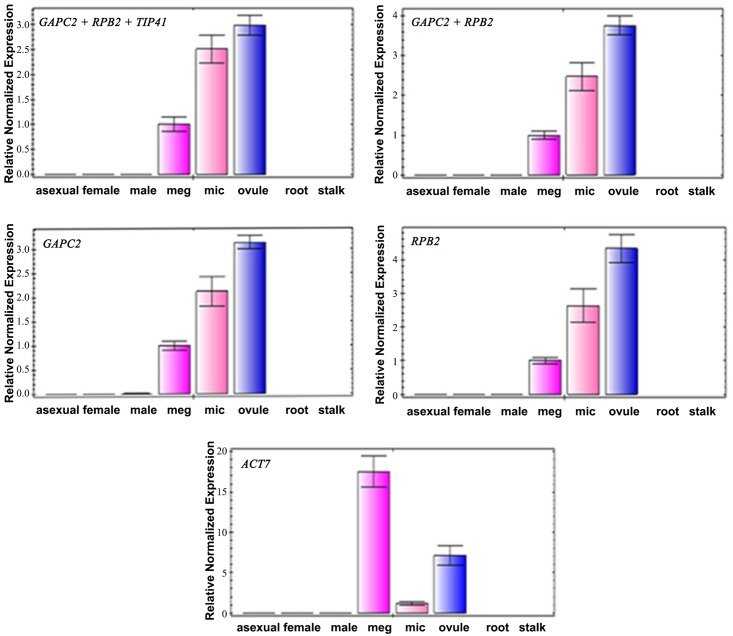

To confirm the reliability of potential reference genes recommended by the combined analyses of three programs (Fig 6) while considering the optimal number of reference genes suggested by geNorm (Fig 5), four combinations of most stable housekeeping genes: APC2 +RPB2 +TIP41, GAPC2 +RPB2, GAPC2 and RPB2, as well as the least stable gene ACT7 were used in the normalization of the target gene C. elongata AGAMOUSE (CeAG). CeAG was identified and cloned (sequence showed in S2 File) utilizing the same processes described for reference genes. The Blastn showed that this gene shared 99% similarity to the genes of Cycas pranburiensis (KP238764), C. elephantipes (KP238762), C. taitungensis (KP238765) and CyAG of C. edentata (AF492455). The relative expression profiles of the target gene were performed in all samples and demonstrated that regardless of combinations of reference genes used, GAPC2 +RPB2 +TIP41, GAPC2 +RPB2, GAPC2 or RPB2, a similar expression patterns of the target gene were obtained. The expression level of CeAG in different samples showed as: ovule > microsporophyll > megasporophyll, and no transcript level was observed in vegetative tissues (female plant leaves, male plant leaves, asexual plant leaves, root and stalk). By contrast, the relative expression of target gene with ACT as reference gene showed a more variable expression pattern, where the transcript level was as follows: megasporophyll > ovule > microsporophyll (Fig 7).

Fig 6. Venn diagrams.

(A) The most stable reference genes present in the first six positions and (B) the least stable genes present in the last seven positions identified by the NormFinder, BestKeeper and geNorm methods. Diagrams were performed with the Venny 2.0.2 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html).

Fig 7. Expression levels of the CeAG gene.

The most stable genes of different combinations (GAPC2 +RPB2 +TIP41, GAPC2 +RPB2, GAPC2 and RPB2) and the least stable gene ACT7 were used for normalization. The results presented are fold changes in relative expression compared to the meg tissue. The data are mean ± SD from three biological replicates. Samples were collected from asexual plant leaf (asexual), female plant leaf (female), male plant leaf (male), megasporophyll (meg), microsporophyll (mic), ovule, root and stalk of C. elongata.

Discussion

In plant molecular biological research, qRT-PCR is the most popular method of gene expression analysis and must be preceded by validated normalization to prevent non-biological event variations. This is particularly challenging for non-model species that do not have a reference genome sequence [5, 28–30]. The C. elongata is an example of a non-model species which is a gymnosperm in the family Cycadaceae. Cycads are considered the earliest separating lineage in extant gymnosperms for which is considered helpful to study the origin and evolution of MADS-box floral organ identity genes. Thus, the identification of suitable reference genes for C. elongata would be of considerable value [15, 31].

To our knowledge, this is the first survey of cloning and expression stability of qRT-PCR reference genes in C. elongata tissues. In our study, thirteen candidate reference genes were successfully cloned and identified, and their consistency of expression was further accessed using three statistical algorithms geNorm, NormFinder and BestKeeper in eight C. elongata tissues. When compared, the results of these three software programs were consistent although some inconsistencies were observed between these methods [32–35], which were due to the different algorithms used by the programs. For all methods, the CeGAPC2 and CeRPB2 genes were consistently selected as more stable whereas CeACT7, CeEF1 and CeUBQ showed the least expression stability.

Similar to our selected control genes, analogous results were observed in Gossypium raimondii [18] for which GAPC2 showed relatively stable expression levels in all tissues (i.e. leaves, shoots, buds and sepals). In previous studies, also found that, GAPC2 was identified as a stable gene for normalization in citrus [26], different coffee cultivars [36] and Brachypodium [37]. For other studies, GAPDH was identified as the most variable reference genes in petunia when assessed during leaf and flower development [38] and in Withania somnifera [35].

Elements of our study were verified by previous work which showed that RPB2, a subunit of RNA polymerase II needed for elongation and mRNA transcription in eukaryotes [39] exhibited the best stable reference gene in Plukenetia volubilis [40] for seed development, and in citrus for leaf samples of different citrus genotypes [41] and litchi in different tissues [42]. However, RPII was classified as the least reliable references in coffee in nitrogen starvation, salt and heat stress [43].

Although ACT is one of the most commonly used reference gene in plants, in C. elongata it ranked last indicating low stability across different tissue samples whichever statistical methods assessed. Expression instability was also described by Czechowski et al. [7], who found ACT2 to have the least stable gene expression among the 27 tested. Similar results were also observed in Nicotiana tabacum with viral infections [44].

We note that EF-1α has been considered a consistent reference gene and ranked as highly effective for use in gene expression studies with teak [27], Picea abies and Pinus pinaster [45]. While we report contrary results, our results corroborate those obtained by Xia et al. and Expósito-Rodríguez et al., which considered EF1-1α the most unstable gene showing low stability in African oil palm and in tomato [8, 46]. In accordance with similar studies of gene expression in teak [27], brazilian pine [5] and rubber tree [47], the reliable reference genes for C. elongata also varied within subsets of samples, suggesting that the most constant expression profile varied between tissues and/or samples even within the same plants. Taken together, these results suggested that reference genes may show a different stability pattern under different conditions or in different plants even within the same plants, which suggests reliable reference genes are highly specific for a particular experimental setting. This argues that a careful evaluation for every individual experimental setup is indeed needed.

It has been reported that the added reference gene has a significant effect on normalization and should be included in calculations [20]. From our results we found that the inclusion of a third reference gene (i. e. GAPC2, RPB2 and TIP41) when considering the total samples was an improvement. The optimal number of internal control genes is frequently confirmed by the threshold ≤ 0.15 [20], nevertheless this is not absolute since small datasets require fewer reference genes than larger ones and previous studies have reported proper normalization with higher cut-off values [27,44]. Therefore our results point out that V2/3 for all tissues is 0.167 which is close to 0.15 and considering the increased costs of more than three reference genes in large scale gene expression profiles, two housekeeping genes in C. elongata is recommended.

To illustrate the actual utility of validated reference genes in this study, the expression pattern of CeAG was examined in C. elongata. AGAMOUS (AG) is the class C MADS-box gene that have been shown to play key roles in the determination of reproductive floral organs such as stamens, carpels and ovules [48]. In Gymnosperms, AGAMOUS is also expressed only in the reproductive structures, which was reported in C. edentata [15] and Ginkgo biloba [49]. Our results demonstrate that the expression pattern of CeAG were comparable across the different internal control combintations tested (GAPC2 +RPB2 +TIP41, GAPC2 +RPB2, GAPC2 or RPB2), which suggested that the relative expression of the target gene was highest in ovule, followed by microsporophyll, megasporophyll and expression less in vegetative tissues (Fig 7). This shows that the use of three or more reference genes is unnecessary supporting our recommendation for the optimal number of control genes. This expression pattern is consistent with the results obtained by Zhang et al. [15] that showed CyAG can only be detected in reproductive tissues of C. edentate. Similarly, GBM5 had a higher expression in ovules than stamens of Ginkgo biloba [49], which confirmed our selection of best stable reference genes. On the other hand, when the most unstable ACT7 was used as reference gene, the expression pattern of the target gene showed a distinct trend toward the highest transcript level in megasporophyll, where it displayed the lowest expression level when appropriate reference genes were used. This indicates that the use of an inappropriate reference genes may cause erroneous results leading us to conclude that, the ACT7 gene is not appropriate for gene expression studies in C. elongata.

In conclusion, the proposed reference genes GAPC2 and RPB2 are suitable for qRT-PCR normalization in different tissues of C. elongata. To our knowledge, this work represents the first attempt to clone, sequence and evaluate commonly used candidate reference genes in C. elongata for the normalization of gene expression analysis using qRT-PCR. It will facilitate further gene expression analyses of target genes in different tissues of C. elongata.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank National Cycads Conservation Center for kindly providing all tissues of Cycas elongata.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The project was supported by the Grant (20150012) from Shenzhen Urban Management to SZ and Grant (SSTLAB-2014-01) from the Public Subject Foundation from Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Southern Subtropical Plant Diversity, Fairylake Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences to HW. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vanguilder HD, Vrana KE, Freeman WM. Twenty-five years of quantitative PCR for gene expression analysis. Biotechniques. 2008; 44(5): 619–26. 10.2144/000112776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubista M, Andrade JM, Bengtsson M, Forootan A, Jonák J, Lind K, et al. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2006; 27(2): 95–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bustin SA, Vladimir B, Garson JA, Jan H, Jim H, Mikael K, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clinical Chemistry. 2009; 55(4): 611–22. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dheda K, Huggett JF, Chang JS, Kim LU, Bustin SA, Johnson MA, et al. The implications of using an inappropriate reference gene for real-time reverse transcription PCR data normalization. Analytical Biochemistry. 2005; 344(344): 141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbl P, Navarro BV, Oliveira LFD, Almeida J, Mosini AC, Santos ALWD, et al. Identification and Evaluation of Reference Genes for Quantitative Analysis of Brazilian Pine (Araucaria angustifolia Bertol. Kuntze) Gene Expression. Plos One. 2015; 10(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2002; 29(1): 4021–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible W-R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant physiology. 2005; 139(1): 5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei X, Mason AS, Yong X, Zheng L, Yang Y, Lei X, et al. Analysis of multiple transcriptomes of the African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) to identify reference genes for RT-qPCR. Journal of Biotechnology. 2014; 184: 63–73. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Immink RGH, Kerstin K, Angenent GC. The 'ABC' of MADS domain protein behaviour and interactions. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2010; 21(1): 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrario S, Immink RG, Angenent GC. Conservation and diversity in flower land. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004; 7(1): 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frohlich MW. An evolutionary scenario for the origin of flowers. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2003; 4(7): 559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theissen G, Melzer R. Molecular mechanisms underlying origin and diversification of the angiosperm flower. Annals of Botany. 2007; 100(3): 603–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YQ, Melzer R, Theißen G. Molecular interactions of orthologues of floral homeotic proteins from the gymnosperm Gnetum gnemon provide a clue to the evolutionary origin of 'floral quartets'. The Plant Journal. 2010; 64(2): 177–90. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theissen G, Becker A, Di Rosa A, Kanno A, Kim JT, Münster T, et al. A short history of MADS-box genes in plants. Plant Molecular Evolution: Springer; 2000. 115–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P, Tan HT, Pwee KH, Kumar PP. Conservation of class C function of floral organ development during 300 million years of evolution from gymnosperms to angiosperms. The Plant Journal. 2004; 37(4): 566–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gramzow L, Weilandt L, Theißen G. MADS goes genomic in conifers: towards determining the ancestral set of MADS-box genes in seed plants. Annals of botany. 2014; 114(7): 1407–29. 10.1093/aob/mcu066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao X, Horvath DP, Chao WS, Yang Y, Wang X, Xiao B. Identification and evaluation of reliable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). International journal of molecular sciences. 2014; 15(12): 22155–72. 10.3390/ijms151222155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun R, He Q, Zhang B, Wang Q. Selection and validation of reliable reference genes in Gossypium raimondii. Biotechnology letters. 2015; 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology. 1990; 215(3): 403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome biology. 2002; 3(7): research0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Ørntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer research. 2004; 64(15): 5245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaffl MW, Tichopad A, Prgomet C, Neuvians TP. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnology letters. 2004; 26(6): 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001; 25(4): 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl MW. Quantification strategies in real-time PCR. AZ of quantitative PCR. 2004; 1: 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silveira ÉD, Alves-Ferreira M, Guimarães LA, da Silva FR, Carneiro VT. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR expression studies in the apomictic and sexual grass Brachiaria brizantha. BMC Plant Biology. 2009; 9(1): 84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan J, Yuan F, Long G, Qin L, Deng Z. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis in citrus. Molecular biology reports. 2012; 39(2): 1831–8. 10.1007/s11033-011-0925-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galeano E, Vasconcelos TS, Ramiro DA, de De Martin V, Carrer H. Identification and validation of quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR reference genes for gene expression analysis in teak (Tectona grandis Lf). BMC research notes. 2014; 7(1): 464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi X, Hu R, Yang Q, Zhang X, Pan L, Chen N, et al. Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in peanut by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2012; 287(2): 167–76. 10.1007/s00438-011-0665-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perini P, Pasquali G, Margis-Pinheiro M, de Oliviera PRD, Revers LF. Reference genes for transcriptional analysis of flowering and fruit ripening stages in apple (Malus× domestica Borkh.). Molecular Breeding. 2014; 34(3): 829–42. 10.1007/s11032-014-0078-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galli V, Borowski JM, Perin EC, da Silva Messias R, Labonde J, dos Santos Pereira I, et al. Validation of reference genes for accurate normalization of gene expression for real time-quantitative PCR in strawberry fruits using different cultivars and osmotic stresses. Gene. 2015; 554(2): 205–14. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melzer R, Wang Y-Q, Theißen G, editors. The naked and the dead: the ABCs of gymnosperm reproduction and the origin of the angiosperm flower. Seminars in cell & developmental biology; 2010; 21: 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang E, Shi S, Liu J, Cheng T, Xue L, Yang X, et al. Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression studies in Platycladus orientalis (Cupressaceae) using real-time PCR. PloS one. 2012; 7(3): e33278 10.1371/journal.pone.0033278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marum L, Miguel A, Ricardo CP, Miguel C. Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in Quercus suber. PloS one. 2012; 7(4): e35113 10.1371/journal.pone.0035113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Y, Lai Z. Reference gene selection for qPCR analysis during somatic embryogenesis in longan tree. Plant Science. 2010; 178(4): 359–65. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh V, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R, Pati PK. Evaluation and Selection of Candidate Reference Genes for Normalization of Quantitative RT-PCR in Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal. PloS one. 2015; 10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz F, Kalaoun S, Nobile P, Colombo C, Almeida J, Barros LM, et al. Evaluation of coffee reference genes for relative expression studies by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Molecular Breeding. 2009; 23(4): 607–16. 10.1007/s11032-009-9259-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong S-Y, Seo PJ, Yang M-S, Xiang F, Park C-M. Exploring valid reference genes for gene expression studies in Brachypodium distachyon by real-time PCR. BMC plant biology. 2008; 8(1): 112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallona I, Lischewski S, Weiss J, Hause B, Egea-Cortines M. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during leaf and flower development in Petunia hybrida. BMC Plant Biology. 2010; 10(1): 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei W, Dorjsuren D, Lin Y, Qin W, Nomura T, Hayashi N, et al. Direct interaction between the subunit RAP30 of transcription factor IIF (TFIIF) and RNA polymerase subunit 5, which contributes to the association between TFIIF and RNA polymerase II. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001; 276(15): 12266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niu L, Tao Y-B, Chen M-S, Fu Q, Li C, Dong Y, et al. Selection of Reliable Reference Genes for Gene Expression Studies of a Promising Oilseed Crop, Plukenetia volubilis, by Real-Time Quantitative PCR. International journal of molecular sciences. 2015; 16(6): 12513–30. 10.3390/ijms160612513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mafra V, Kubo KS, Alves-Ferreira M, Ribeiro-Alves M, Stuart RM, Boava LP, et al. Reference genes for accurate transcript normalization in citrus genotypes under different experimental conditions. PloS one. 2012; 7(2): e31263 10.1371/journal.pone.0031263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong H-Y, Chen J-W, Li C-Q, Chen L, Wu J-Y, Chen J-Y, et al. Selection of reliable reference genes for expression studies by reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR in litchi under different experimental conditions. Plant cell reports. 2011; 30(4): 641–53. 10.1007/s00299-010-0992-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Carvalho K, Bespalhok Filho JC, Dos Santos TB, de Souza SGH, Vieira LGE, Pereira LFP, et al. Nitrogen starvation, salt and heat stress in coffee (Coffea arabica L.): identification and validation of new genes for qPCR normalization. Molecular biotechnology. 2013; 53(3): 315–25. 10.1007/s12033-012-9529-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu D, Shi L, Han C, Yu J, Li D, Zhang Y. Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in virus-infected Nicotiana benthamiana using quantitative real-time PCR. PLoS One. 2012; 7(9): e46451 10.1371/journal.pone.0046451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Vega-Bartol JJ, Santos RR, Simões M, Miguel CM. Normalizing gene expression by quantitative PCR during somatic embryogenesis in two representative conifer species: Pinus pinaster and Picea abies. Plant cell reports. 2013; 32(5): 715–29. 10.1007/s00299-013-1407-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Müller OA, Grau J, Thieme S, Prochaska H, Adlung N, Sorgatz A, et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Validation of Reference Genes in Infected Tomato Leaves for Quantitative RT-PCR Analyses. PloS one. 2015; 10(8): e0136499 10.1371/journal.pone.0136499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long X, He B, Gao X, Qin Y, Yang J, Fang Y, et al. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during latex regeneration in rubber tree. Gene. 2015; 563(2): 190–5. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dreni L, Kater MM. MADS reloaded: evolution of the AGAMOUS subfamily genes. New Phytologist. 2014; 201(3): 717–32. 10.1111/nph.12555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lovisetto A, Baldan B, Pavanello A, Casadoro G. Characterization of an AGAMOUS gene expressed throughout development of the fleshy fruit-like structure produced by Ginkgo biloba around its seeds. BMC evolutionary biology. 2015; 15(1): 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.