Abstract

Objective

More effective tobacco prevention and cessation programs require in-depth understanding of the mechanism by which multiple factors interact with each other to affect smoking behaviors. Stress has long been recognized as a risk factor for smoking. However, the underlying mediation and moderation mechanisms are far from clear. The purpose of this study was to examine the role of negative emotions in mediating the link between stress and smoking and whether this indirect link was modified by resilience.

Methods

Survey data were collected using audio computer assisted self-interview (ACASI) from a large random sample of urban residents (n=1249, mean age = 35.1, 45.3% male) in Wuhan, China. Perceived stress, negative emotions (anxiety, depression), resilience were measured with reliable instruments also validated in China. Self-reported smoking was validated with exhaled carbon monoxide.

Results

Mediation analysis indicated that two negative emotions fully mediated the link between stress and intensity of smoking (assessed by number of cigarettes smoked per day, effect = .082 for anxiety and .083 for depression) and nicotine dependence (assessed by DSM-IV standard, effect = .134 for anxiety and .207 for depression). Moderated mediation analysis demonstrated that the mediation effects of negative emotions were negatively associated with resilience.

Conclusions

Results suggest resilience interacts with stress and negative emotions to affect the risk of tobacco use and nicotine dependence among Chinese adults. Further research with longitudinal data is needed to verify the findings of this study and to estimate the effect size of resilience in tobacco intervention and cessation programs.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, Stress, Resilience, Moderated mediation, Nicotine dependence

Introduction

The Need for More Research to Inform Tobacco Cessation in China

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality across the globe, particularly China (WHO, 2011). Every year, 1.2 million (15%) of China's total deaths are attributed to tobacco use; and tobacco-related deaths are projected to double in the next 20 years (Gu et al., 2009). Still, 52.5% of Chinese men and 2.4% of Chinese women smoke and furthermore, the behavior shows an upward trend (Ding et al., 2014). Despite the growing need to curb the tobacco epidemic (Zhang, Liu, Wang, & Jia, 2014), evidence-based programs for smoking cessation and intervention are limited in China (Kim et al., 2012), except some interventions among adolescents (Chou et al., 2006; Shek & Yu, 2011; Unger, Yan, et al., 2001; Wu, Detels, Zhang, Li, & Li, 2002). Effective and cost-efficient tobacco cessation programs in China will benefit from more in-depth etiological research (Gruder et al., 2013), especially research that focuses on how multiple psychosocial risk/protective factors interact with each other to affect tobacco use (Koplan, Eriksen, Chen, & Yang, 2013).

Smoking as a Coping Strategy for Negative Emotions

One mechanism for persistent tobacco use is the coping strategy theory - people simply use tobacco as a self-medication against negative emotions (Khantzian, 1997). There is a high co-morbidity between smoking and negative emotions (Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, & Kassel, 2009), particularly anxiety and depression (Leventhal & Zvolensky, 2014). Negative emotions are associated with multiple stages of the smoking trajectory, including initiation (Leventhal, Ray, Rhee, & Unger, 2012), progression from experimenting to regular smoking (Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, Rodgers, & Cuevas, 2011), and from regular smoking to nicotine dependence (McKenzie, Olsson, Jorm, Romaniuk, & Patton, 2010). Negative emotions are also associated with failure in tobacco cessation treatment (Hitsman et al., 2013). It is of great significance to consider negative emotions when investigating factors related to smoking.

Negative Emotions as the Mediators between Stress and Smoking

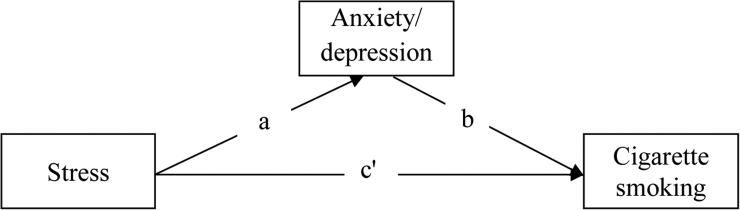

Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression often result from stressful events experienced in daily life, suggesting a mediation mechanism by which negative emotions bridge stress with smoking (Figure 1). The relationship between stress and tobacco use has been supported by empirical studies (Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003; Kendzor et al., 2014; Niaura, Shadel, Britt, & Abrams, 2002; Slopen et al., 2012; Slopen et al., 2013), including studies in China (Booker et al., 2007; Cui, Rockett, Yang, & Cao, 2012; Unger, Li, et al., 2001). In addition to a direct effect, stress may be indirectly associated with tobacco use and nicotine dependence through negative emotions. Stressful and traumatic life events are demonstrated to be strong predictors of negative emotions (Reutter & Bigatti, 2014); while tobacco is used as a coping strategy to deal with negative emotions as described in the previous paragraph. If this mediation mechanism is supported by data, it will shed light on the etiology of tobacco use, and provide evidence supporting the development of more effective tobacco prevention and treatment programs. However, no reported studies have examined such mediating mechanism in predicting tobacco use among Chinese population.

Figure 1.

Negative emotions mediate the relationship between stress and smoking

Note. Indirect effect = a*b and direct effect = c’

Resilience and Tobacco Smoking

In contrast to stress and negative emotions that are positively associated with tobacco use, one important factor that has been linked to reduced risk of tobacco use is resilience (Veselska et al., 2009). Resilience can be considered as the capability of an individual to adapt to stressful situations or experiences and to “bounce back” (Johnson & Wiechelt, 2004; Masten, 2014; Rutter, 2012). Resilience consists of three closely related components related to physical, mental and social processes, each of which may alter the linkage from stress to tobacco use (Chen, Wang, & Yan, 2015). Implications of resilience on tobacco use and prevention have been recognized in the literature (Braverman, 1999). Recent research indicates that individuals with higher levels of resilience are less likely to initiate smoking (Veselska et al., 2009), to smoke cigarettes in the past month (Skrove, Romundstad, & Indredavik, 2013), and to become nicotine dependent (Goldstein, Faulkner, & Wekerle, 2013). Similar research findings among Chinese adolescents have also been reported (Arpawong et al., 2010). Although these findings are very encouraging, little is known about the underlying mechanisms by which resilience may reduce the risk of tobacco use and nicotine dependence, especially when Chinese adults are concerned.

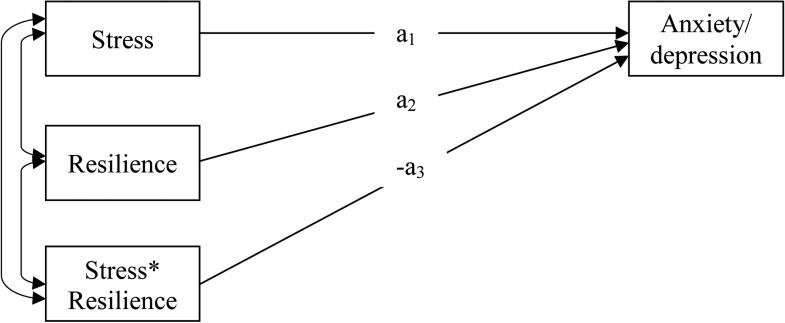

Resilience May Moderate the Effect of Stress on Negative Emotions

One mechanism to explain the negative relation between resilience and tobacco use could be that resilience is a moderator of stress. By definition, more resilient individuals will be less likely to be affected by stress (Johnson & Wiechelt, 2004; Masten, 2014; Rutter, 2012). Even if affected by adverse or traumatic events, resilient individuals may be less likely to feel anxious or become depressed; and even if a negative emotion appears, it may not last long (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, 2006). This moderation effect can be expressed with Figure 2: the association between stress and anxiety/depression is negatively modified by resilience (-a3). Accumulative data from previous research indicates a significant effect of resilience in moderating a wide range of stress on negative emotions, including daily stress (Bitsika, Sharpley, & Bell, 2013), stressful life events (Peng et al., 2012), trauma (Roy, Carli, & Sarchiapone, 2011), maltreatments (Goldstein et al., 2013), and violent events (Nrugham, Holen, & Sund, 2010).

Figure 2.

Resilience moderates the effect of stress on negative emotions

Note: A significant a3 has been reported in many studies (see citations in the text)

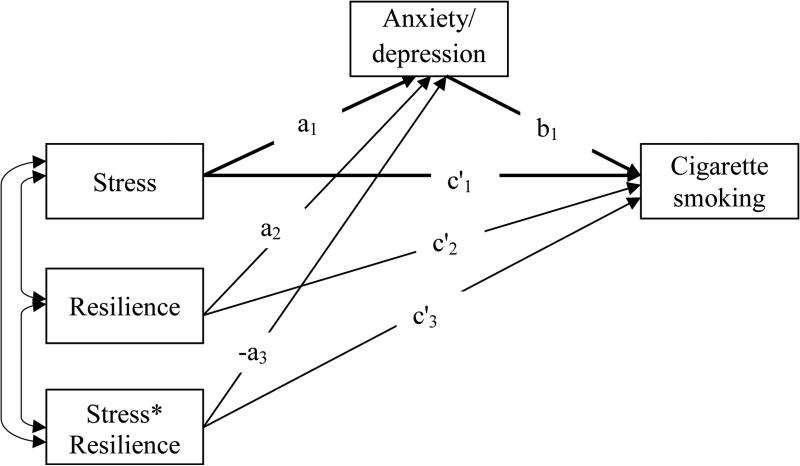

An Integrative Moderated Mediation Model

A moderated mediation effect model (Figure 3) is possible given the indirect effect model of negative emotions in mediating stress and tobacco use (Figure 1) and the moderation effect model of resilience in alleviating the association between stress and negative emotions (Figure 2). From the moderated mediation model it can be seen that (1) when the association between stress and negative emotions is modified by resilience (-a3), the mediation effect of negative emotions (i.e., a1*b1) is also modified; (2) the direct effect of stress on smoking may also be modified by resilience if c’3 is statistically significant; and (3) this integrative model makes it possible to estimate the moderation effect of resilience on the mediator (i.e., -a3) and outcome (i.e., c’3) variables, and the “net” mediation effect (i.e., a1*b1) after controlling for the mediation moderated by resilience (i.e., -a3*b1).

Figure 3.

A proposed moderated mediation model of cigarette smoking

Note. Model coefficients are labeled in the figure.

Purposes of the Current Study

With survey data collected from a large random sample of adults from a city in China, the purpose of this study is two-fold: (1) to investigate the indirect effect of negative emotions (i.e., anxiety and depression) in mediating the association between stress and tobacco use/nicotine dependence, (2) to test the integrative moderated mediation model with stress as the predictor variable, resilience as the moderator, anxiety and depression as the mediators and tobacco use as the outcome. The ultimate goal is to advance our understanding of the mechanisms by which psychosocial factors lead to tobacco use and to provide new data supporting the development of behavioral interventions for more effective tobacco use prevention and cessation programs.

Methods

Participants and Sampling

Participants were adults aged between 18 and 45 years sampled in Wuhan, China. As the capital of Hubei Province, Wuhan is located in central China with a total population of 9.2 million and a per capita GDP of $10,335 (Statistical Bureau of Wuhan, 2012). The participants were randomly sampled with a novel GIS/GPS-assisted method. The geographic areas of the seven urban districts of Wuhan were each divided into mutually exclusive geographic units (geounits for short) with a computer-generated grid system with grid size of 100m by 100m. A total of 60 geounits with residential housing were then selected using the random digits method (Cochran, 1977). Within each selected geounit, approximately 20 participants were recruited from households with one person per gender per household. For households with more than one eligible participant, only one was selected using the Kish method (Kish, 1949). Among all eligible persons approached, 92% agreed to participate. More geonunits were allocated to districts with higher population density to optimize cost-effectiveness (Levy & Lemeshow, 1999).

Data collection

Data collection was conducted during 2011-13. A team of 10-12 trained data collectors was dispatched to the field to recruit participants and to administer the survey. Data were collected using the Migrant Health and Behavior Questionnaire (MHBQ) (Chen, Stanton, Gong, Fang, & Li, 2009) with assistance of the audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) technique. The questionnaire was constructed in language that people with elementary education can easily comprehend. The interview was conducted in a private room in the participant's home or other places of the participant's preference, primarily a nearby community health center. After a brief 5-minute training for using the ACASI, participants answered the questions by themselves independently. Data collectors were available to answer questions when participants were completing the survey. Among the 1,370 participants who completed the survey, 121 were excluded because they indicated in the survey that less than 80% of their answers were “truthful”, yielding a final sample of 1,249 for the analysis. A comparison between the 121 participants and the final sample indicated that these individuals did not differ from the retained sample except for a relatively lower education level.

The survey protocol and the survey questionnaire were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Wuhan CDC and the Human Investigation Committee at Wayne State University (WSU).

Variables and their Measurement

Predictor variable

The level of global stress, measured with the Perceived Stress scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) was used as the predictor variable. This 10-item instrument assesses levels of perceived stress by measuring the degree to which situations in one's daily life are appraised as stressful, unpredictable, and uncontrollable during the past month. The instrument was previously validated in Chinese populations and showed good reliability (Yang & Huang, 2003). An example item is: “In the last month, how often have you felt there were too many things to deal with?” Individual items were rated on the standard 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) and 5 (always) and Cronbach's alpha of the scale was .93. Mean scores were computed for analysis such that higher scores indicated higher levels of stress.

Mediator variables

Two negative emotions, anxiety and depression, were used as mediators and they were assessed with the Anxiety (6 items, α=.88) and Depression subscales (5 items, α=.87) from the widely used Brief Symptoms Inventory (Derogatis, 1993). This inventory was validated in Chinese populations and showed good reliability (Liu, Chen, Cao, & Jiao, 2013; Wang, Kelly, Liu, Zhang, & Hao, 2013). In these two subscales, a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) was used to assess negative emotions experienced in the past seven days. Mean scores were computed for analysis such that higher scores indicated stronger negative emotions.

Moderator variable

Resilience was used as the moderator variable. This variable was measured using the Essential Resilience Scale (ERS, Chen, Wang, & Yan, 2015). The ERS consists of three subscales (i.e., physical, emotional, and social resilience) with 5 items per subscale. Participants were asked to rate a list of 15 items with the question: “To what extent do you agree with each of the following statements?” An example item for physical resilience is: “I can continue my tasks even when I am very thirsty or hungry”. An example item for emotional resilience is: “I can quickly get over sadness and feeling depressed”. An example item for social resilience is: “I always rise up quickly from big setbacks and failures”. Individual items were rated on a standard 5-point Likert scale varying from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This scale was developed and validated through a pilot study among Chinese urban residents (n = 80) with good reliability (.91) for the total and three subscales (.88, .87, .74). The Cronbach's alphas in current study were .92, .82, .84, .82 for ERS and its three subscales, respectively. Mean scores were computed for analysis such that larger scores indicated higher levels of resilience.

Outcome variables

Two outcome variables were intensity of smoking and nicotine dependence. (1) Smoking intensity was measured based on self-reported number of cigarettes smoked on a typical day with 3 = high intensity (20 or more cigarettes per day), 2 = moderate intensity (10-19 cigarettes per day), 1 = low intensity (1-9 cigarettes per day), and 0 = no smoking (less than 1 cigarette per day) (Pierce, Messer, White, Cowling, & Thomas, 2011). (2) Nicotine dependence was measured using the 12-item Nicotine Dependence Scale (Kandel et al., 2005) based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The scale covers seven key dimensions of nicotine dependence (i.e., tolerance, withdrawal, impaired control, unsuccessful quit attempt, time spent on tobacco use, escaping important events, and continuous use despite physical or psychological problems). Smokers received one point for each of the seven dimensions if they answered “yes” to any of the questions on that dimension. Cronbach's alpha of the scale was .99; and dependence scores were computed for individual smokers such that higher scores indicating more severe nicotine dependence (Hu, Griesler, Wall, & Kandel, 2014). Smokers with a dependence score ≥ 3 were classified as being nicotine dependent (Kandel et al., 2005). Self-reported smoking was correlated with exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) as a biomarker, and the correlation coefficients were .68 for days smoked in the past 30 days and .62 for nicotine dependence, indicating satisfactory validity of self-reported smoking (Marrone, Paulpillai, Evans, Singleton, & Heishman, 2010).

Demographic variables

Demographic variables included age (in years), gender (male and female), marital status (married and not married), education (middle school or less, high school, college or more), and monthly income ($). These variables were used to describe the sample characteristics, while age, gender and education were also used as covariates in moderation and mediation analyses.

Analytical Strategies

It is challenging to determine the complex moderated mediation relationships among multiple variables with cross-sectional data. To avoid reverse impact while testing the mediation effect, we chose a relatively long-term distal factor (i.e., stress in past month) as the predictor of two relatively short-term proximal mediators (i.e., the 7-day anxiety and depression) and two current behavioral measures as outcomes (i.e., intensity of smoking and nicotine dependence). To test the proposed relationships among these study variables, a total of four models were used to test the two emotion measures (i.e., anxiety and depression) in mediating the association between stress and the two outcome measures (i.e., smoking intensity and nicotine dependence) (Figure 1). 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effects were obtained using the bootstrapping method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

A series of simple moderation models were constructed to test whether resilience buffers the effect of stress on smoking and on negative emotions. Based on the literature as well as results from the simple mediation and moderation analyses, a series of moderated mediation models were constructed to test the role of resilience in moderating the mediation effect (Figure 3), following the approach by Preachers and colleagues (Preachers et al, 2007).

The mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation modeling analyses were conducted with the software SPSS version 22.0 (IMB Corp., 2013). The macro PROCESS was used for these analyses (Hayes, 2013). The Johnson-Neyman technique was used to test the significance of the mediation effect. In all statistical analyses, type I error was set at p < .05 level (two-sided). Modeling analysis by gender was not pursued because of a lack of statistical power due to the fewer number of female smokers (<10%). Instead, gender was included together with age and education as covariates.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Smoking Behaviors

Results in Table 1 indicate that among the 1249 participants, 45.3% were male, with a mean age of 35.1 (SD = 7.5), 76.0% married, 74.6% had a high school or more education, and 80.0% with monthly income greater than $150. Among the total participants, 35.1% were current smokers, 22.1% daily smokers, 11.4% heavy smokers, and 26.3% nicotine dependent.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Smoking Behaviors of the Study Sample, by Gender

| Male (n=566) n (%) | Female (n=683) n (%) | Total (N=1249) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 34.9 (7.6) | 35.3 (7.5) | 35.1 (7.5) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 410 (72.4) | 539 (78.9) | 949 (76.0) |

| Not married | 156 (27.6) | 112 (21.1) | 256 (24.0) |

| Education | |||

| Middle school | 146 (25.8) | 172 (25.2) | 318 (25.4) |

| High school | 204 (36.0) | 239 (35.0) | 443 (35.5) |

| College or higher | 216 (38.2) | 272 (39.8) | 488 (39.1) |

| Monthly income | |||

| ≤$150 | 101 (17.8) | 149 (21.8) | 250 (20.0) |

| $150-$300 | 236 (41.7) | 363 (53.1) | 599 (48.0) |

| >$300 | 229 (40.4) | 171 (25.0) | 400 (32.0) |

| Current smoking status | |||

| Yes | 387 (68.4) | 52 (7.6) | 439 (35.1) |

| Frequency of smoking | |||

| Daily smokers | 261 (46.1) | 15 (2.2) | 276 (22.1) |

| Intermittent smokers | 126 (22.3) | 37 (5.5) | 163 (13.0) |

| Amount of smoking | |||

| Heavy smokers | 138 (24.4) | 5 (0.7) | 143 (11.4) |

| Light smokers | 324 (57.2) | 148 (21.6) | 472 (37.7) |

| Nicotine dependence | |||

| Yes | 307 (54.2) | 22 (3.2) | 329 (26.3) |

Correlational Analysis

Results in Table 2 indicate that perceived stress was positively associated with both anxiety (r = .59, p < .001) and depression (r = .59, p < .001) and the two negative emotions were, in turn, positively associated with intensity of smoking (r = .06, p < .05 for anxiety; r = .08, p < .01 for depression) and nicotine dependence (r = .07, p < .05 for anxiety; r = .10, p < .001 for depression). In addition, the resilience measures were all negatively associated with each of the two negative emotions (p < .001 for total, emotional and social resilience and p < .05 for physical resilience). These results provide preliminary support for the proposed mediation and moderated mediation models.

Table 2.

Key variables and Pearson correlation coefficients, N = 1249

| Variables | Mean(SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Stress | 2.55 (0.62) | 1.00-5.00 | - | |||||||

| 2 Total resilience | 3.40 (0.63) | 1.00-5.00 | −.05 | - | ||||||

| 3 Physical resilience | 3.28 (0.76) | 1.00-5.00 | .02 | .83** | - | |||||

| 4 Emotional resilience | 3.52 (0.71) | 1.00-5.00 | −.09** | .91*** | .62*** | - | ||||

| 5 Social resilience | 3.39 (0.70) | 1.00-5.00 | −.06* | .89*** | .55*** | .86*** | - | |||

| 6 Anxiety | 1.99 (0.64) | 1.00-5.00 | .59*** | −.10*** | −.07* | −.10*** | −.09** | - | ||

| 7 Depression | 2.07 (0.71) | 1.00-5.00 | .59*** | −.13*** | −.07* | −.14*** | −.11*** | .83*** | - | |

| 8 Intensity of smoking | 0.83 (1.02) | 0-3.00 | .04 | −.02 | −.03 | .01 | −.02 | .06* | .08** | - |

| 9 Nicotine dependence | 1.43 (2.34) | 0-7.00 | .08** | −.03 | −.05 | −.01 | −.01 | .07* | .10*** | .78*** |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Mediation Analysis

Results in the “Without moderation” row of Table 3 indicate significant indirect effects of anxiety and depression in mediating the association between perceived stress and smoking intensity of smoking after controlling for age, gender, and education (effect = .082 for anxiety, p < .01, 44% variance explained by the model; and .083 for depression, p < .01, 44% variance explained by the model) and nicotine dependence (effect = .134 for anxiety, p < .01, 38% variance explained by the model; and .207 for depression, p < .01, 35% variance explained by the model).

Table 3.

The Moderated Indirect Effect from Stress to Smoking and Nicotine Dependence through Anxiety and Depression

| Levels of resilience | Mediator variable | Mediation effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of smoking | Levels of nicotine dependence | ||

| Anxiety | |||

| Without moderation | 1.99 | .082** | .134** |

| With moderation | |||

| Total resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.04 | .082** | .131* |

| Mean | 1.99 | .081** | .129* |

| One SD > Mean | 1.94 | .080** | .127* |

| Physical resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.04 | .078** | .121 |

| Mean | 1.99 | .080** | .123 |

| One SD > Mean | 1.94 | .081** | .125 |

| Emotional resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.05 | .090** | .146* |

| Mean | 2.02 | .085** | .138* |

| One SD > Mean | 1.97 | .080** | .130* |

| Social resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.02 | .082** | .135* |

| Mean | 1.99 | .081** | .134* |

| One SD > Mean | 1.96 | .080** | .132* |

| Depression | |||

| Without moderation | 2.07 | .083** | .207** |

| With moderation | |||

| Total resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.14 | .087** | .213** |

| Mean | 2.07 | .083** | .204** |

| One SD > Mean | 2.00 | .079** | .195** |

| Physical resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.13 | .082** | .198** |

| Mean | 2.07 | .081** | .197** |

| One SD > Mean | 2.01 | .081** | .197** |

| Emotional resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.13 | .095** | .234*** |

| Mean | 2.07 | .088*** | .215*** |

| One SD > Mean | 2.01 | .080** | .197*** |

| Social resilience | |||

| One SD < Mean | 2.13 | .086** | .220** |

| Mean | 2.07 | .083** | .210** |

| One SD > Mean | 2.02 | .079** | .201** |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Moderation Analysis

Results from moderation analysis indicated that emotional resilience significantly buffered the effect of stress on negative emotions (effect = −.05 for anxiety, p < .01, 36% variance explained by the model; and effect = −.08 for depression, p < .01, 36% variance explained by the model) after controlling for age, gender, and education. The variance uniquely accounted for by the interaction was 0.2% and 0.4% for anxiety and depression respectively. The moderation effect from total resilience scale scores and the physical and social resilience subscale scores were not statistically significant.

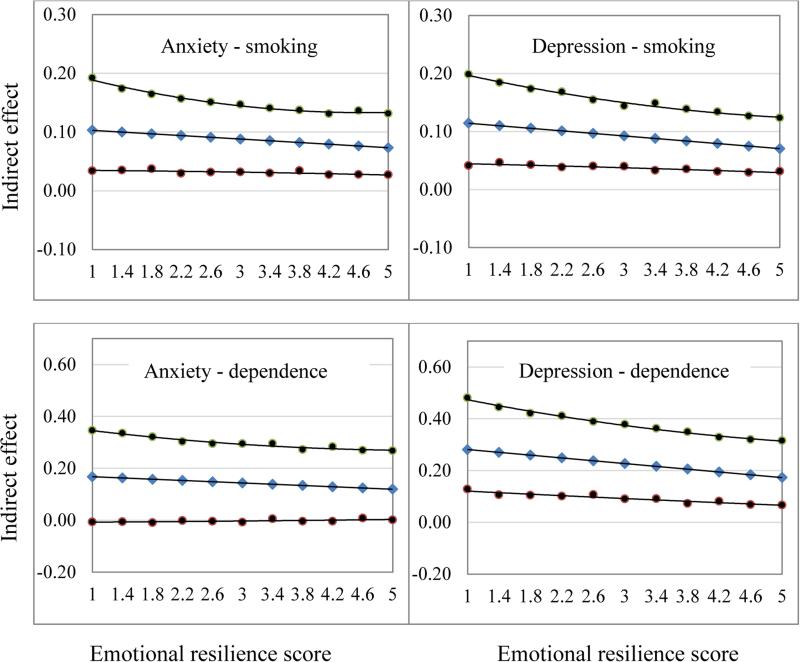

Moderated Mediation Analysis

Results under the row entitled “With moderation” in Table 3 indicate that the mediation effects of the two emotion measures were significant at the three levels of resilience (p < .01 for all except physical resilience, Johnson Neyman test); and the mediation effect decreased as resilience scores increased. For example, when the total resilience scores increased from one SD below the mean to one SD above the mean, the indirect effect of depression in mediating the effect of stress on nicotine dependence declined from 0.213 (p < .01) to .195 (p < .01). A similar pattern was also observed for the three resilience subscales (i.e., physical, mental and social) with one exception for physical resilience in modifying the mediation effect of anxiety on nicotine dependence. Among the four resilience measures, only the moderation effect of emotional resilience was statistically significant for anxiety (a3 = −.054, p < .05, 44% variance explained by the model) and depression (a3 = −.085, p < .01, 36% variance explained by the model). Figure 4 presents the moderation effect of emotional resilience with the 95% confidence bands.

Figure 4.

The mediation effect moderated by emotional resilience (95% Confidence band) of anxiety (left column) and depression (right column) in bridging the relationship between stress and smoking intensity (upper panel) and nicotine dependence (lower panel).

Discussion

Understanding the complex relationship among the risk and protective factors in predicting tobacco use is of great significance to advance the etiology of tobacco use and to support more effective smoking prevention intervention and cessation treatment. In this study, we attempted to investigate one of such relationships by testing a moderated mediation mechanism to explain the relationship between stress and smoking. Our results indicate a full mediation effect of negative emotions (i.e., anxiety and depression) between stress and smoking; a significant moderation effect of resilience in buffering impact of stress on negative emotions; and a significant moderated mediation effect where resilience moderated the indirect relationship from stress to smoking through negative emotions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of this type to test the effect of resilience in moderating the indirect relationship between stress and smoking mediated by negative emotions. Findings of this study add new data on the etiology of tobacco use. If the findings of this study can be replicated with longitudinal data, these findings can be used to support the development of more effective programs for smoking prevention and cessation.

Negative Emotions in Mediating the Relationship between Stress and Smoking

Findings of our study suggest that the relationship between perceived stress and smoking (as measured by smoking intensity and nicotine dependence) is fully mediated by negative emotions. Previous research has demonstrated that stress is associated with negative emotions (Reutter & Bigatti, 2014) and negative emotions are associated with increased risk of smoking (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009). We integrated these two relationships in this study with a mediation modeling approach. Although further longitudinal data is needed to verify this finding, our result suggests that stress would not be a risk factor for smoking unless it causes negative emotional responses. Therefore, it may be more effective to treat negative emotions than to manage stress for tobacco use prevention and cessation. Indeed, previous research shows a significant effect of behavioral intervention targeting negative emotions and antidepressant medication (Hall et al., 2002).

The Moderation Effect of Resilience

The significant stress—negative emotions—smoking pathway observed in this study also suggests that either reducing stress or reducing the impact of stress on negative emotions would be another effective strategy in reducing tobacco use. Previously, stress management has been incorporated into smoking cessation programs aiming to help smokers develop adaptive coping skills, thereby reducing the use of tobacco (Tsourtos & O'Dwyer, 2008). However, randomized clinical trials indicate the lack of effect of such interventions (Limm et al., 2011). Furthermore, findings from other trials failed to show additional effect of stress management above the regular tobacco cessation treatment (e.g., nicotine replacement treatment) (D'Angelo et al., 2005). Findings of this study suggest that instead of stress management, focusing on resilience training could be a more promising approach.

Resilience as a capability to adapt to stressful circumstances (Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2014), can be improved by active learning and purposeful training (Sood, Prasad, Schroeder, & Varkey, 2011). Three components of resilience are considered essential: anticipation, flexibility, and bounce-back (Chen et al., 2015). Highly resilient persons (1) can anticipate adverse or stressful events before they occur and be well prepared to deal with them; (2) are more flexible and have the ability to buffer the impact of adverse or stressful events without significant maladjustment; and (3) can recover (bounce-back) quickly and adequately from the adverse or stressful impact (Chen et al., 2015). Although stress in life is inevitable; these three capabilities will enable individuals to better adapt to stress while maintaining health and well-being (Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2014).

Resilience enhancement programs are available for health promotion (Prince-Embury & Saklofske, 2014), but few have been used for smoking prevention and cessation purposes. Prior studies find that resilience has a significant protective effect on substance use after exposure to stressful life events, but their results are based on adolescent samples with a primary focus on the protective factors (e.g., family support) that promote resilience (Arpawong et al., 2010; Arpawong et al., 2015). Our findings provide empirical evidence supporting the potentials to adapt existing resilience training programs or devise new programs for tobacco control purpose among Chinese adults. Evidence-based tobacco prevention and smoking cessation programs are rare in China, especially so for the adult population (Kim et al., 2012). One significant barrier is the lack of empirical data supporting the development of such programs. The current study contributes to the literature by supplying such data to enhance our understanding of smoking etiology among the Chinese adult population and suggesting the potential success of improving resilience as a personal capability in smoking intervention and cessation programs.

Limitations and conclusions

There are several limitations to this study. First, data used for this study were cross-sectional in nature. Although we purposefully chose predictor (i.e., stress) occurred in the past month, mediators (i.e., anxiety and depression) in the past week, and outcome variables (i.e., smoking intensity and nicotine dependence) as current behaviors, the reverse causality cannot be ruled out. For example, prior research shows a reciprocal relationship between negative emotions and tobacco use (Ameringer & Leventhal, 2010) as well as a bidirectional relationship between negative emotions and stress (Calvete, Orue, & Hankin, 2015; Masten et al., 2005). Hence, longitudinal data are needed to further validate the findings of current study. Second, the study was conducted in China. Caution is needed when the findings of this study are to be generalized to other countries/places, particularly those with different social and cultural backgrounds as they are related to resilience, stress, negative emotions and tobacco use. Third, stress was measured using participants’ perception rather than a concrete list of life events, which could be less objective. However, perceived stress is a good proxy of experienced life events and is more relevant in predicting negative emotions than the number of life events as suggested by literature (Cohen et al., 1983).

Despite the limitations, this study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to simultaneously test moderation and mediation effect in one model to disentangle the complex mechanisms by which three key influential factors (resilience, stress, and negative emotions) interact with each other to predict smoking and nicotine dependence among Chinese adult population. While our findings suggest the potential importance of resilience training in tobacco intervention and cessation programs, future studies are implied to replicate the results with longitudinal data in different populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH R01 MH086322

Contributor Information

Dr Yan Wang, University of Florida, Epidemiology, 2004 Mowry Road, Gainesville, UnitedStates

Dr Xinguang Chen, Univeristy of Florida, Epidemiology, Gainesville, United States, jimax.chen@phhp.ufl.edu.

Dr Jie Gong, Wuhang CDC, Wuhan, China, gongjie@whcdc.org.

Dr Yaqiong Yan, Wuhang CDC, Wuhan, China, samwhcdc@hotmail.com.

References

- American Psychiatric Association A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed (1.0. ed.). American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ameringer KJ, Leventhal AM. Applying the Tripartite Model of Anxiety and Depression to Cigarette Smoking: An Integrative Review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(12):1183–1194. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq174. doi: Doi 10.1093/Ntr/Ntq174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpawong TE, Sun P, Chang MC, Gallaher P, Pang Z, Guo Q, Unger J. Family and personal protective factors moderate the effects of adversity and negative disposition on smoking among Chinese adolescents. [Twin Study]. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(9):1367–1389. doi: 10.3109/10826081003686041. doi: 10.3109/10826081003686041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpawong TE, Sussman S, Milam JE, Unger JB, Land H, Sun P, Rohrbach LA. Post-traumatic growth, stressful life events, and relationships with substance use behaviors among alternative high school students: a prospective study. Psychology & Health. 2015;30(4):475–494. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.979171. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.979171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Kassel JD. Adolescent smoking and depression: evidence for self-medication and peer smoking mediation. Addiction. 2009;104(10):1743–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02617.x. doi: DOI 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J. Declining alternative reinforcers link depression to young adult smoking. Addiction. 2011;106(1):178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03113.x. doi: DOI 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsika V, Sharpley CF, Bell R. The Buffering Effect of Resilience upon Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Parents of a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2013;25(5):533–543. doi: DOI 10.1007/s10882-013-9333-5. [Google Scholar]

- Booker CL, Unger JB, Azen SP, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lickel B, Johnson CA. Stressful life events and smoking behaviors in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(11):1085–1094. doi: 10.1080/14622200701491180. doi: Doi 10.1080/14622200701491180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman MT. Research on resilience and its implications for tobacco prevention. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S67–72. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Orue I, Hankin BL. Cross-lagged associations among ruminative response style, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2015;34(3):203–220. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2015.34.3.203. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB. Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(4):585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Gong J, Fang X, Li X. Personal Social Capital Scale: an instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(2):306–317. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn020. doi: cyn020 [pii]10.1093/her/cyn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang Y, Yan Y. The Essential Resilience Scale: Instrument development and prediction of perceived health and behavior. Stress and Health (accepted) 2015 doi: 10.1002/smi.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Li Y, Unger JB, Xia J, Sun P, Guo Q, Johnson CA. A randomized intervention of smoking for adolescents in urban Wuhan, China. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42(4):280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.002. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WJ. Sampling Techniques. John Wiley & Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Rockett IR, Yang T, Cao R. Work stress, life stress, and smoking among rural-urban migrant workers in China. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Bmc Public Health. 2012;12:979. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-979. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo MES, Reid RD, Holz S, Irvine J, Segal RJ, Blanchard CM, Pipe A. Is stress management training a useful addition to physician advice and nicotine replacement therapy during smoking cessation in women? Results of a randomized trial. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;20(2):127–134. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Gebel K, Oldenburg BF, Wan X, Zhong X, Novotny TE. An early-stage epidemic: a systematic review of correlates of smoking among Chinese women. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(4):653–661. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9367-1. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9367-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Faulkner B, Wekerle C. The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruder CL, Trinidad DR, Palmer PH, Xie B, Li LM, Johnson CA. Tobacco Smoking, Quitting, and Relapsing Among Adult Males in Mainland China: The China Seven Cities Study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(1):223–230. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts116. doi: Doi 10.1093/Ntr/Nts116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu DF, Kelly TN, Wu XG, Chen J, Samet JM, Huang JF, He J. Mortality Attributable to Smoking in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(2):150–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902. doi: Doi 10.1056/Nejmsa0802902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Munoz RF, Hartz DT, Maude-Griffin R. Psychological intervention and antidepressant treatment in smoking cessation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):930–936. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.930. doi: DOI 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis. Guilford Press; New York, New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hitsman B, Papandonatos GD, McChargue DE, DeMott A, Herrera MJ, Spring B, Niaura R. Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction. 2013;108(2):294–306. doi: 10.1111/add.12009. doi: Doi 10.1111/Add.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Griesler PC, Wall MM, Kandel DB. Reciprocal associations between cigarette consumption and DSM-IV nicotine dependence criteria in adolescent smokers. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1518–1528. doi: 10.1111/add.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Wiechelt SA. Introduction to the special issue on resilience. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39(5):657–670. doi: 10.1081/ja-120034010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Schaffran C, Griesler P, Samuolis J, Davies M, Galanti R. On the measurement of nicotine dependence in adolescence: Comparisons of the mFTQ and a DSM-IV-based scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(4):319–332. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi027. doi: DOI 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(2):270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Reitzel LR, Rios DM, Scheuermann TS, Pulvers K, Ahluwalia JS. Everyday Discrimination Is Associated With Nicotine Dependence Among African American, Latino, and White Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(6):633–640. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt198. doi: Doi 10.1093/Ntr/Ntt198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. doi: Doi 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Chen W, Kolodziej M, Wang X, Wang VJ, Ziedonis D. A Systematic Review of Smoking Cessation Intervention Studies in China. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(8):891–899. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within household. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1949;44:380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Koplan JP, Eriksen M, Chen L, Yang GH. The value of research as a component of successful tobacco control in China. Tob Control. 2013;22:1–3. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051054. doi: DOI 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Ray LA, Rhee SH, Unger JB. Genetic and Environmental Influences on the Association Between Depressive Symptom Dimensions and Smoking Initiation Among Chinese Adolescent Twins. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(5):559–568. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr253. doi: Doi 10.1093/Ntr/Ntr253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, Depression, and Cigarette Smoking: A Transdiagnostic Vulnerability Framework to Understanding Emotion-Smoking Comorbidity. Psychol Bull. 2014 doi: 10.1037/bul0000003. doi: 10.1037/bul0000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy PS, Lemeshow S. Sampling of Populations-Methods and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Limm H, Gundel H, Heinmuller M, Marten-Mittag B, Nater UM, Siegrist J, Angerer P. Stress management interventions in the workplace improve stress reactivity: a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(2):126–133. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.054148. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.054148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.-b., Chen H.-f., Cao B, Jiao F. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Brief Symptom Inventory in high school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;21(1):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone GF, Paulpillai M, Evans RJ, Singleton EG, Heishman SJ. Breath carbon monoxide and semiquantitative saliva cotinine as biomarkers for smoking. Human Psychopharmacology-Clinical and Experimental. 2010;25(1):80–83. doi: 10.1002/hup.1078. doi: Doi 10.1002/Hup.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, Tellegen A. Developmental Cascades: Linking Academic Achievement and Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms Over 20 Years. Dev Psychol. 2005;41(5):733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Olsson CA, Jorm AF, Romaniuk H, Patton GC. Association of adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety with daily smoking and nicotine dependence in young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1652–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. doi: DOI 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Shadel WG, Britt DM, Abrams DB. Response to social stress, urge to smoke, and smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nrugham L, Holen A, Sund AM. Associations Between Attempted Suicide, Violent Life Events, Depressive Symptoms, and Resilience in Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198(2):131–136. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43a2. doi: Doi 10.1097/Nmd.0b013e3181cc43a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Zhang JJ, Li M, Li PP, Zhang Y, Zuo X, Xu Y. Negative life events and mental health of Chinese medical students: The effect of resilience, personality and social support. Psychiatry Research. 2012;196(1):138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.006. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Messer K, White MM, Cowling DW, Thomas DP. Prevalence of heavy smoking in California and the United States, 1965-2007. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. JAMA. 2011;305(11):1106–1112. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.334. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince-Embury S, Saklofske DH, editors. Resilience interventions for youth in diverse populations. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reutter KK, Bigatti SM. Religiosity and Spirituality as Resiliency Resources: Moderation, Mediation, or Moderated Mediation? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2014;53(1):56–72. doi: Doi 10.1111/Jssr.12089. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Carli V, Sarchiapone M. Resilience mitigates the suicide risk associated with childhood trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133(3):591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. [Review]. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(2):335–344. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000028. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek DT, Yu L. A review of validated youth prevention and positive youth development programs in Asia. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011;23(4):317–324. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2011.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrove M, Romundstad P, Indredavik MS. Resilience, lifestyle and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescence: the Young-HUNT study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(3):407–416. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0561-2. doi: DOI 10.1007/s00127-012-0561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Dutra LM, Williams DR, Mujahid MS, Lewis TT, Bennett GG, Albert MA. Psychosocial Stressors and Cigarette Smoking Among African American Adults in Midlife. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(10):1161–1169. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts011. doi: Doi 10.1093/Ntr/Nts011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kontos EZ, Ryff CD, Ayanian JZ, Albert MA, Williams DR. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9-10 years: a prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(10):1849–1863. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0262-5. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood A, Prasad K, Schroeder D, Varkey P. Stress Management and Resilience Training Among Department of Medicine Faculty: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(8):856–861. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1640-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Bureau of Wuhan . Wuhan Statistical Yearbook-2012. China Statistics Press; Beijing: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tsourtos G, O'Dwyer L. Stress, stress management, smoking prevalence and quit rates in a disadvantaged area: has anything changed? Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2008;19(1):40–44. doi: 10.1071/he08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Li Y, Johnson CA, Gong J, Chen XG, Li CY, Lo AT. Stressful life events among adolescents in Wuhan, China: Associations with smoking, alcohol use, and depressive symptoms. Int J Behav Med. 2001;8(1):1–18. doi: Doi 10.1207/S15327558ijbm0801_01. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Yan L, Chen X, Jiang X, Azen S, Qian G, Anderson Johnson C. Adolescent smoking in Wuhan, China: baseline data from the Wuhan Smoking Prevention Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(3):162–169. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veselska Z, Geckova AM, Orosova O, Gajdosova B, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA. Self-esteem and resilience: The connection with risky behavior among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Kelly BC, Liu T, Zhang G, Hao W. Factorial structure of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18 among Chinese drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.017. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO [December 22, 2014];WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. 2011 2011, from http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/

- Wu ZY, Detels R, Zhang JP, Li V, Li JH. Community-based trial to prevent drug use among youths in Yunnan, China. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(12):1952–1957. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1952. doi: Doi 10.2105/Ajph.92.12.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TZ, Huang HT. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24(9):760–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Jia C. Mediation of smoking consumption on the association of perception of smoking risks with successful spontaneous smoking cessation. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(4):677–681. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9378-y. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9378-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]