Significance

We identified a membrane protein that is unique to Plasmodium (malaria-causing parasite) and its phylogenetic family members. This protein is localized at the parasite’s surface, binds transfer RNAs (tRNAs) specifically, and directs the import of exogenous tRNAs into the parasite. In the absence of this protein, the parasite’s development is severely reduced. We propose that Plasmodium diverts tRNAs from host cells to support its life cycle and discuss the biological pertinence of this unprecedented host–pathogen interaction, as well as the possible fate of imported tRNAs.

Keywords: tRNA, Plasmodium, trafficking

Abstract

The malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites are transmitted to vertebrates by mosquitoes. To support their growth and replication, these intracellular parasites, which belong to the phylum Apicomplexa, have developed mechanisms to exploit their hosts. These mechanisms include expropriation of small metabolites from infected host cells, such as purine nucleotides and amino acids. Heretofore, no evidence suggested that transfer RNAs (tRNAs) could also be exploited. We identified an unusual gene in Apicomplexa with a coding sequence for membrane-docking and structure-specific tRNA binding. This Apicomplexa protein—designated tRip (tRNA import protein)—is anchored to the parasite plasma membrane and directs import of exogenous tRNAs. In the absence of tRip, the fitness of the parasite stage that multiplies in the blood is significantly reduced, indicating that the parasite may need host tRNAs to sustain its own translation and/or as regulatory RNAs. Plasmodium is thus the first example, to our knowledge, of a cell importing exogenous tRNAs, suggesting a remarkable adaptation of this parasite to extend its reach into host cell biology.

In Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria, the nuclear genome has a minimal set of 45 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, with only one gene per tRNA isoacceptor (1). This single-gene feature is an exception among eukaryotes, where tRNA genes are usually present in multiple copies. Discrepancies between codon use and expression levels of corresponding tRNAs were also observed in Plasmodium falciparum blood stages (2). These considerations raise the possibility that, under at least some conditions, the parasite may need an additional source of tRNAs and possibly rely on the import of exogenous tRNAs.

tRNA trafficking is only known to occur between compartments within eukaryotic cells. For example, nuclear-encoded tRNAs can transit from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, return to the nucleus, and be re-exported to the cytoplasm, depending on the tRNA maturation status and cellular environment (3). Cytoplasmic tRNAs are also imported into mitochondria (and chloroplasts) and participate in protein synthesis, mainly to supplement incomplete sets of organellar tRNAs (4). Which tRNAs are imported, and the mechanisms used for their transport, diverge considerably among organisms (5, 6). With these considerations in mind, we identified a Plasmodium genome-encoded protein that has motifs associated with tRNA binding. We show that this surface protein binds and imports exogenous tRNAs from the extracellular space into the parasite and that its deletion affects parasite development.

Results

Identification of Plasmodium tRip.

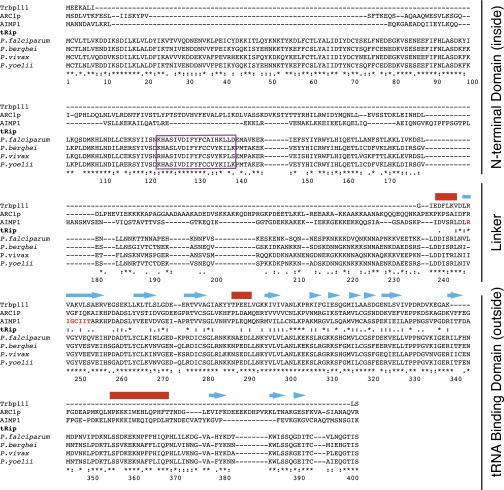

A widely distributed tRNA binding motif is exemplified by a minimal tRNA binding protein—Trbp111—that was first identified in Aquifex aeolicus (7). This free-standing homodimeric protein specifically binds tRNA by recognizing its characteristic elbow structure. Other proteins that contain this motif include the yeast aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cofactor 1 (ARC1p) (8), the metazoan AIMP1 (9), and Toxoplasma gondii Tg-p43 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase interacting proteins (10). Like Trbp111, ARC1p and AIMP1 bind tRNAs. Consistently, Tg-p43 is part of a multisynthetase complex, suggesting a tRNA-binding capability. We identified a gene encoding a 402-amino-acid Plasmodium protein (PF3D7_1442300 in P. falciparum) with a Trbp111-orthologous domain at its C terminus and an N-terminal region exhibiting a transmembrane helix motif (https://www.predictprotein.org:443/) (Fig. S1). Anticipating that this protein might import exogenous tRNAs, we designated it as tRip (tRNA import protein). We define tRip orthologs as proteins containing a C-terminal tRNA binding domain and a predicted transmembrane helix motif, which we found only in Apicomplexa, a phylum of parasitic protists that contains other human pathogens such as Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium, in addition to Plasmodium (Fig. S2).

Fig. S1.

Identification of a new tRNA binding protein in Plasmodium. The sequence of the S. cerevisiae ARC1p was used as a bait to screen the P. falciparum genome. A unique protein (PF3D7_1442300), encoded by a gene of 1,440 nucleotides and located on chromosome 14, was identified; it contains one intron (231 nucleotides long), and the mature mRNA codes for a protein of 402 amino acids long. Three other plasmodial tRip sequences (P. berghei, P. vivax, and P. yoelii) (www.plasmodb.org/plasmo/) are also shown. In eukaryotes, the Trbp111-like sequence was also found at the N or C terminus of methionyl-, phenylalanyl-, tyrosyl-, and lysyl-tRNA synthetases (48, 49) and occasionally also displayed a cytokine-active heptapeptide (highlighted in red within the AIMP1 sequence) (12, 50, 51). tRip did not display this heptapeptide, but contained a short region that is likely to form a transmembrane helix (purple box). The characteristic folding, as determined by the X-ray structure of the TyrRS N-terminal Trpb111-like fragment (52), is schematized above the alignment (helices are indicated with red lines and β-sheets with blue arrows).

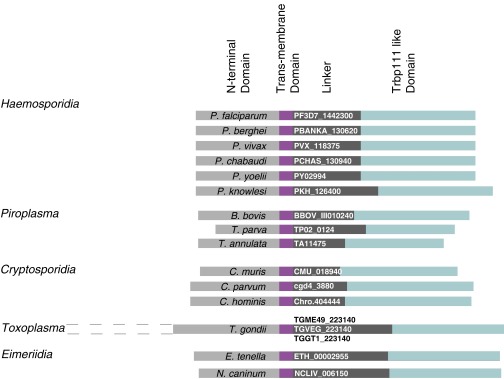

Fig. S2.

Identification of tRip homologs in other Apicomplexa genomes. The amino acid sequence of PftRip was used as a bait to retrieve similar proteins from the eukaryotic pathogen database (eupathdb.org/eupathdb/). Outside plasmodial genes, other sequences matched the same global organization of tRip: an N-terminal domain (light gray), a variable linker (dark gray), and a conserved C-terminal Trpb111-like domain (blue). N-terminal sequences of these orthologs diverged significantly among families. For example, Toxoplasma genes code for an additional N-terminal domain (indicated by dotted lines, not used in transmembrane domain predictions). tRip homologs displayed predicted transmembrane domains characterized by HTM > 0.6 (purple, https://www.predictprotein.org:443/); however, for some sequences, topological predictions varied from one submission to the other. A tRip homolog containing a predicted transmembrane domain (HTM > 0.6) was also identified in Trichomonas vaginalis (TVAG_328570). As this is the only genome from the phylum Trichomonadida sequenced thus far, it was difficult to interpret this information. Among other sequenced genomes available in the database, tRip homologs were found in Kinetoplastids (Leishmania and Trypanosoma), yet the reliabilities of transmembrane domain predictions were too low to be considered. Finally, no tRip homolog was found in Microsporida, Diplomonadida and Amoebozoa.

P. falciparum tRip Binds Human tRNAs.

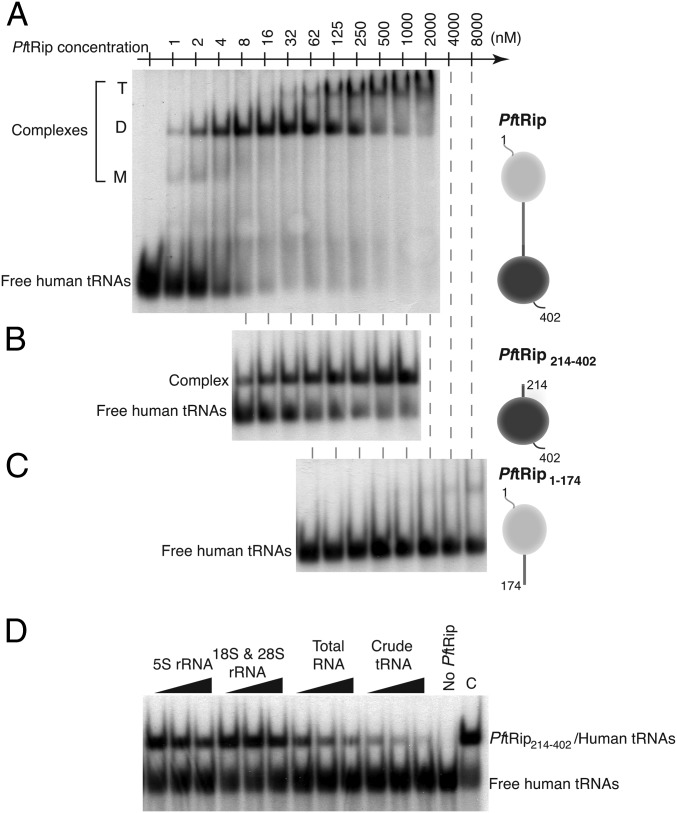

In an in vitro assay, recombinant P. falciparum protein PftRip binds human native unfractionated tRNAs (Fig. 1A). The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 5 nM is of the same order of magnitude as that reported for Trbp111 (32 nM) (7) and ARC1p (5–10 nM) (11), and more than one order of magnitude lower than that observed for AIMP1 (200 nM) (12). To delineate PftRip tRNA binding activity, this experiment was repeated with fragments PftRip1–174 (containing the transmembrane helix) and PftRip214–402 (containing the Trbp111-like domain). Only the C-terminal module (PftRip214–402) binds tRNAs, with an apparent Kd of 15 nM (Fig. 1 B and C). These experiments suggest that PftRip has a similar or higher affinity for tRNAs than Trbp111, ARC1p, and AIMP1 and that the C-terminal domain of the protein is responsible for this binding activity.

Fig. 1.

Binding capacity and specificity of recombinant PftRip for tRNAs. Band shift assays were performed with radiolabeled crude extracts of human tRNA and increasing concentrations of (A) PftRip, (B) PftRip214–402, and (C) PftRip1–174. Bound tRNAs were visible at three different positions corresponding to monomeric (M), dimeric (D), and tetrameric (T) forms of PftRip. (D) Competition assays were conducted in the presence of RNA from different species (Xenopus laevis 5S rRNA, calf liver 18S and 28S rRNAs, total human RNA and crude extracts of human tRNA). C, control experiment without RNA competitor.

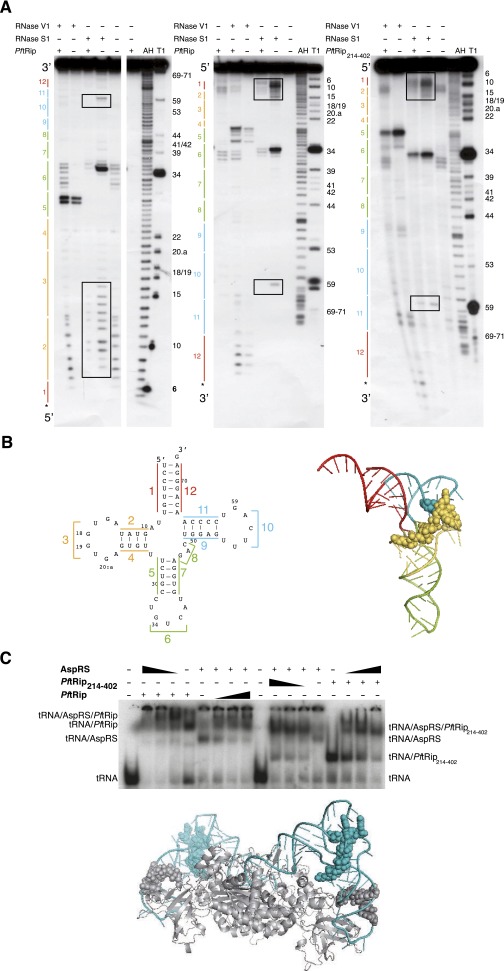

To investigate the specificity of PftRip214–402 for tRNAs compared with other RNAs, we conducted competition experiments with different pools of RNAs: (i) 5S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), (ii) 18S and 28S rRNAs, (iii) total RNAs, including tRNAs, and (iv) unfractionated tRNAs. Only extracts containing tRNAs (total RNAs or crude tRNAs) competed efficiently with a preformed complex between labeled human tRNAs and PftRip214–402 (Fig. 1D). We then carried out an RNA footprinting analysis to identify contact points between PftRip and tRNAs. PftRip binds to the outside corner of the L-shaped tRNA molecule (Fig. S3 A and B). To further characterize tRNA recognition, we determined whether PftRip could still engage the tRNA in the yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS)/tRNAAsp complex (13). AspRS recognizes the “inside” of the L-shaped tRNA. This experiment showed that both PftRip and AspRS bind simultaneously to tRNAAsp (Fig. S3C). The formation of this ternary complex confirms that PftRip binds only to the outside of the L-shaped tRNA structure. A similar ternary complex has been observed for tRNAIle, Trbp111, and isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (14).

Fig. S3.

PftRip footprint on yeast tRNAAsp. (A) Autoradiographs of RNase V1 (cuts double-stranded and structured RNA regions) and RNase S1 (cuts single-stranded RNA regions) cleavage patterns of tRNAAsp in the presence (+) or in the absence (−) of PftRip or PftRip214–402. The tRNAAsp molecule was [32P] labeled at its 5′ (Left) or 3′ (Center and Right) end. The tRNA architecture described in B is schematized on the left side and nucleotide positions are indicated on the right side of the autoradiographs. Controls without RNases (with or without the PftRip recombinant proteins), as well as alkaline hydrolysis (AH) and RNase T1 (T1) ladders, were run simultaneously. Protections were only considered when present in all three experiments. The tRNA anticodon domain (regions 5, 6, and 7) was somewhat protected from S1 and simultaneously became accessible to V1 in the presence of PftRip214–402, suggesting long-range structural changes in the tRNA on binding. However, these reactivity changes toward S1 and V1 were intensified with PftRip, indicating that the N-terminal domain of tRip caused additional steric hindrance. (B) Secondary (Left) and tertiary (Right) structures of tRNAAsp. Each tRNA domain is indicated in a different color: in red (acceptor arm formed by strands 1 and 12), yellow (d-branch, formed by strands 2, 3, and 4), green (anticodon/variable region-branch, strands 5, 6, 7, and 8), and blue (T-branch, strands 9, 10, and 11). Protections of nucleotides within the D and T branches against RNases (squared in A) are shown with yellow and blue spheres, respectively. (C) Simultaneous binding of yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) and PftRip214–402 on the same tRNAAsp molecule and model of their potential interaction. tRNAAsp was incubated with either PftRip and AspRS (Left) or PftRip214–402 and AspRS (Right). The interactions based on footprinting experiments were modeled on the crystal structure of the yeast tRNAAsp (blue)/AspRS (gray) complex (13). Gray spheres indicate the protection of tRNAAsp by the AspRS N-terminal extension (38) and blue spheres correspond to PftRip footprinting.

Expression and Subcellular Localization of tRip in P. berghei.

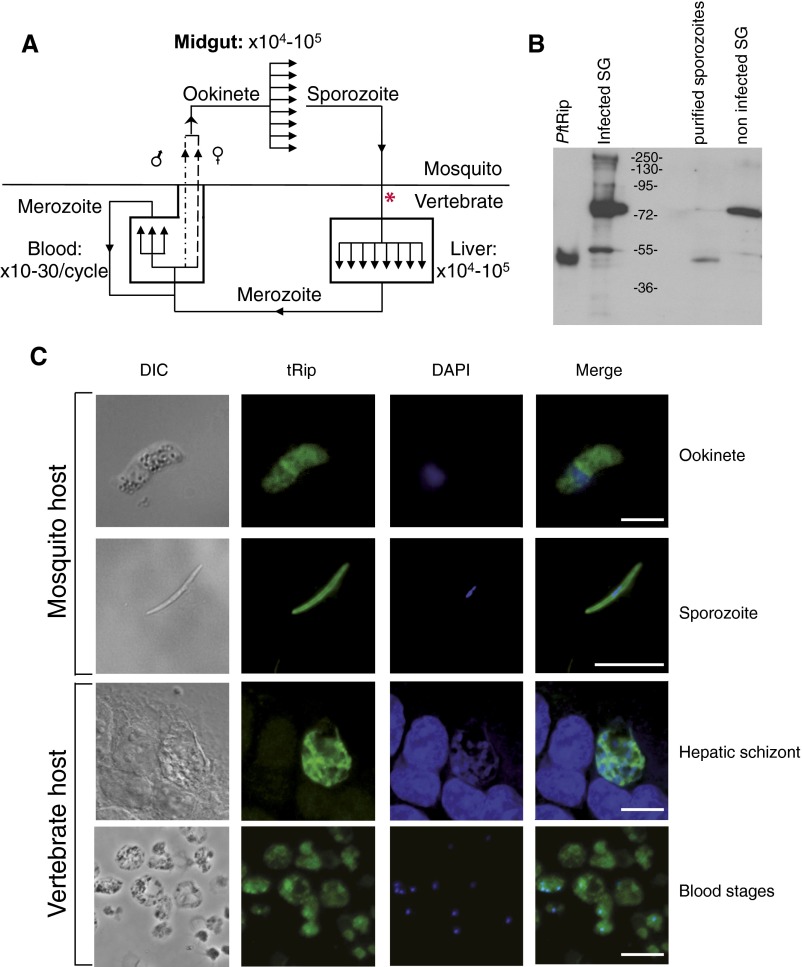

The Plasmodium life cycle is complex, involving several parasite stages. The parasite multiplies in the midgut of the mosquito vector and inside hepatocytes (15) and erythrocytes (16) in the mammalian host (Fig. S4A). Analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data from P. falciparum and P. yoelii (plasmodb.org/plasmo/) indicates that tRip is produced virtually constitutively during the parasite life cycle, i.e., in asexual and sexual blood stages (17–19), mosquito forms (20), and pre-erythrocytic stages (21, 22). Likewise, Toxoplasma (23) or Cryptosporidium (24) transcriptomic databases do not show any significant variations in tRip mRNA expression. Immunofluorescence assays with purified anti-PftRip214–402 antibodies (Fig. S4B) confirmed the presence of tRip in P. berghei extracellular ookinete and sporozoite stages and intracellular hepatocytic and erythrocytic stages (Fig. S4C).

Fig. S4.

Plasmodium life cycle and tRip expression. (A) The cycle of vertebrate infection starts when a mosquito injects sporozoites into the host (see asterisk). Sporozoites invade hepatocytes (entering the liver stage), multiply asexually, and produce tens of thousands of merozoites per infected hepatocyte (15). Merozoites exit the liver and develop repeatedly in red blood cells (blood stages) to produce 10–30 new merozoites per intraerythrocytic cycle (16). Some of the erythrocytic merozoites differentiate into gametocytes (sexual forms, dashed lines). Schizonts are not shown but are another stage that occurs as part of the intraerythrocytic cycle. Fertilization takes place in mosquitoes where gametocytes are ingested during a blood meal and then mature and fuse, leading to zygotes. Zygotes develop into ookinetes, which traverse the mosquito midgut wall and form oocysts. In 8–15 d, each oocyst produces and releases 104–105 sporozoites, which invade the mosquito salivary glands, completing the cycle. (B) Specificity of anti-PftRip214–402. Recombinant PftRip, A. stephensi infected salivary glands (SG), purified sporozoites, and noninfected A. stephensi SG were probed with anti-PftRip214–402. Strong additional signals were observed only in extracts of crude infected and noninfected mosquito SG, indicating that the cross-reactive protein at 72 kDa is not from parasites. (C) Detection of tRip in P. berghei ookinetes (fertilized form of the parasite found in the mosquito), sporozoites, hepatic schizonts (liver stages), and P. berghei blood stages was assessed using immunofluorescence with anti-tRip214–402 antibodies from rabbit. Cells were treated with DAPI (blue) and anti-rabbit FITC antibody (green). Overlay panels show the merged images. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) DIC, differential interference contrast.

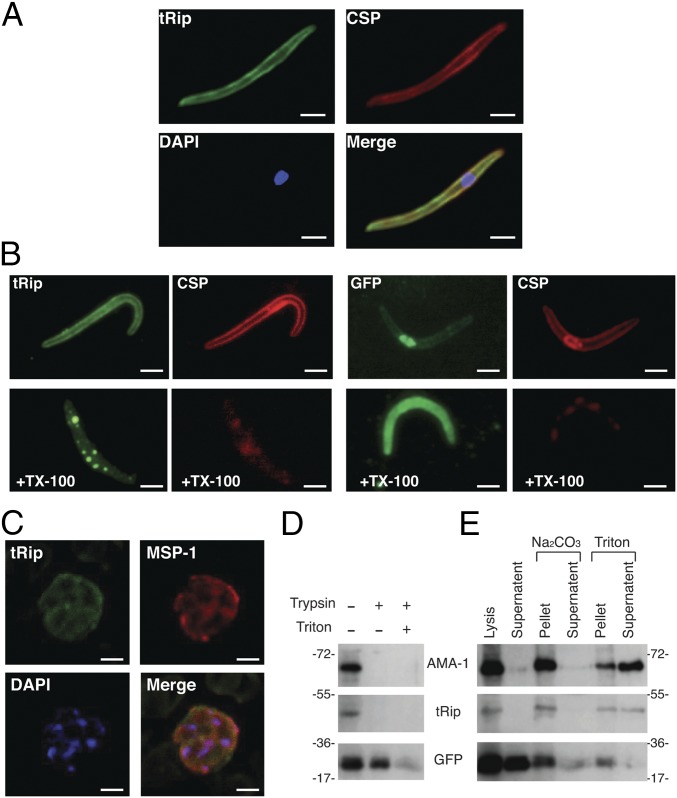

Assays using salivary gland sporozoites revealed similar peripheral fluorescence staining for tRip and the major surface protein, CSP (circumsporozoite protein; Fig. 2A). As the sporozoite pellicle contains an outer membrane (plasma membrane) and two inner membranes, we used the differential solubility characteristics of these membranes toward Triton X-100 to more precisely localize tRip (25). In untreated sporozoites, the fluorescence signals generated by tRip and CSP were evenly distributed at the parasite periphery (Fig. 2B). Fluorescence at the periphery was lost following outer membrane disruption with Triton X-100. This observation demonstrates that tRip is anchored to the plasma membrane of the sporozoite, presumably via its protein transmembrane helix motif (Fig. S1), thus enabling interaction with exogenous tRNAs.

Fig. 2.

tRip localization. (A) Coimmunolocalization assays on P. berghei sporozoites. The major sporozoite surface protein CSP and tRip were probed with anti-CSP antibodies and anti-PftRip214–402, respectively, and the sporozoite nucleus was stained with DAPI. (B) Extraction of tRip with Triton X-100 (TX-100). TX-100 selectively removes the plasma membrane and its associated proteins (CSP and tRip), whereas the inner membrane complex is resistant to this treatment (25). Sporozoite integrity is shown by GFP staining, with CSP staining shown to verify successful Triton X-100 extraction. (Scale bars, 2 µm.) (C) Subcellular localization of tRip in asexual blood-stage parasites of P. berghei. The schizont of P. berghei was doubly labeled with mouse anti-MSP-1 antibody (surface marker, red) and rabbit anti-tRip antibody (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). (Scale bars, 5 μm.) (D) Protease protection assays on blood-stage parasites. Assays were performed with schizonts freed from erythrocytes, treated with trypsin, and probed with anti-PftRip214–402 antibody. GFP was used as a cytosolic control, digested by trypsin only under denaturing conditions (+ Triton). (E) Carbonate vs. Triton extraction of membrane proteins from blood-stage parasites (schizonts). Both tRip and the apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1) (41) were found in the membrane pellet after Na2Co3 treatment and were released into the supernatant only on Triton treatment.

Additionally, in blood-stage parasites, tRip and the surface protein MSP-1 colocalize (Fig. 2C). Protease protection assays on the parasite blood stage confirmed this cell surface localization (Fig. 2D) because signals corresponding to AMA-1 (apical membrane antigen 1) and tRip both vanished on trypsin treatment. Comparison of carbonate vs. detergent extraction showed that tRip behaves like AMA-1 and is only found in the reaction supernatant after Triton extraction and not after lysis or Na2CO3 treatment, indicating that it is an integral membrane protein (Fig. 2E).

Plasmodium Sporozoites Import Exogenous tRNAs.

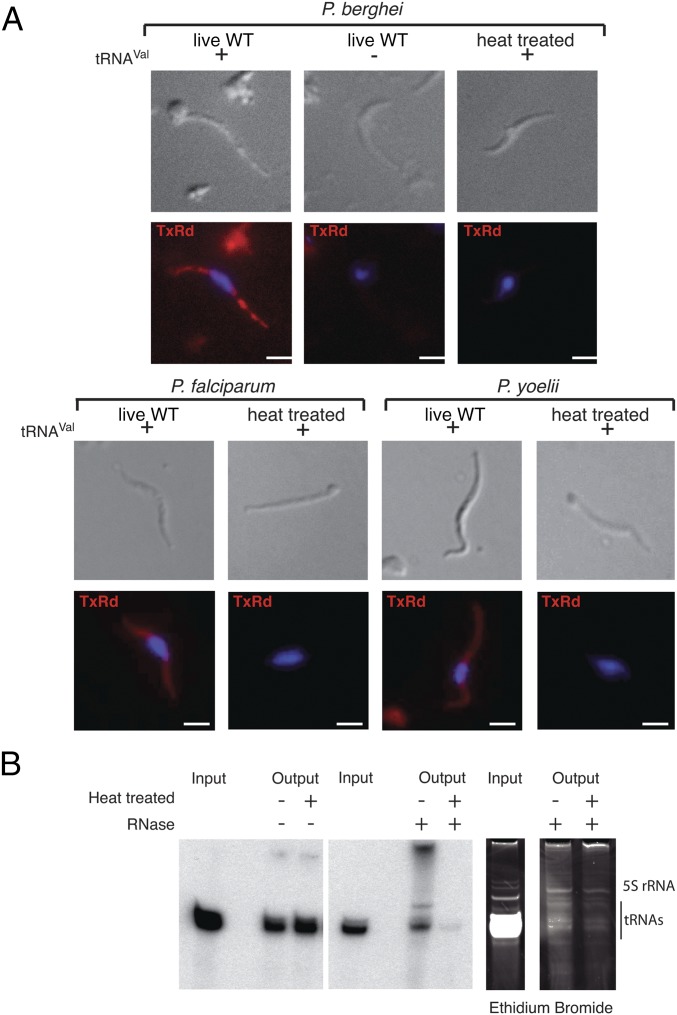

All Apicomplexa have in common the sporozoite stage. Unlike blood stages, the sporozoite is an accessible extracellular stage, which is characterized by its motility and its ability to traverse cells (26–28) without forming a parasitophorous vacuole. Thus, this parasite stage has an opportunity to directly interact with host tRNAs. For these reasons, we tested the ability of tRip to uptake exogenous tRNAs into P. berghei sporozoites. A FISH experiment was performed with Escherichia coli tRNAVal and live or heat-treated sporozoites (50 °C for 30 min). Import of E. coli tRNAVal was observed only in live WT parasites (Fig. 3A). tRNA import was also observed with sporozoites of two other Plasmodium species: P. falciparum and P. yoelii (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Import of tRNAs in Plasmodium sporozoites. (A) P. berghei, P. yoelii, and P. falciparum WT sporozoites were incubated with (+) or without (−) E. coli tRNAVal and were subjected to FISH. Due to high sequence similarities between mammalian and plasmodial tRNAs, E. coli tRNAVal was chosen as a template so that a specific FISH probe could be designed [3′ end-labeled with Texas Red (TxRd)] that does not cross-hybridize with any Plasmodium endogenous tRNAs. On tRNA import, about 80% of sporozoites (WT P. berghei, P. yoelii, and P. falciparum) hybridized the fluorescent probe. (Scale bars, 2 µm.) (B) Radioactive tRNAs from mouse Hepa1-6 cells were cosedimented with both infectious and noninfectious P. berghei sporozoites in the absence (Left) and presence (Center and Right) of RNase A. Following extracellular RNase treatment, intracellular sporozoite endogenous tRNAs were undamaged (Right), and exogenously added radiolabeled tRNAs were observed within living sporozoites only (Center), indicating tRNA import had occurred. Additional bands correspond to tRNA aggregation resulting from phenol extraction.

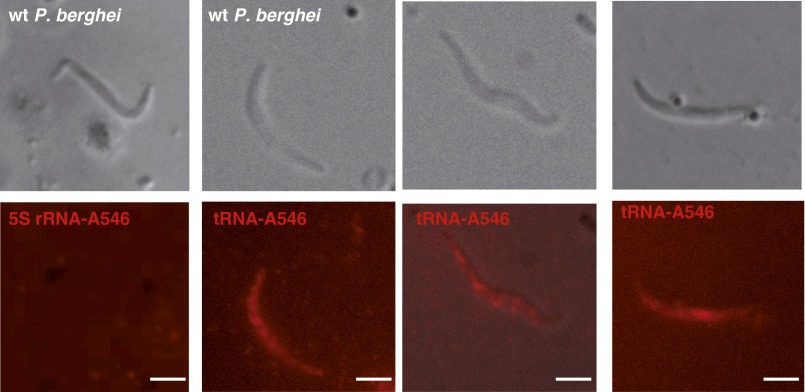

To examine whether this import is specific for tRNAs (as implied by the RNA binding assays above; Fig. 1D), live P. berghei sporozoites were incubated with Alexa Fluor-labeled in vitro-transcribed E. coli tRNAVal and with human 5S rRNA (control). The fluorescent E. coli tRNAVal transcript entered and accumulated inside the parasite, whereas the fluorescent 5S rRNA did not (Fig. S5). Radiolabeled full-length tRNAs from mouse hepatocytes (Hepa1-6 cells) were protected from extracellular RNase treatment inside live but not heat-treated sporozoites (Fig. 3B). Based on these results, we conclude that full-length tRNAs enter sporozoites by an active process.

Fig. S5.

tRNA import in P. berghei sporozoites. Direct visualization of imported Alexa Fluor-labeled in vitro transcribed E. coli tRNAVal and human 5S ribosomal RNA. (Scale bars, 2 µm.)

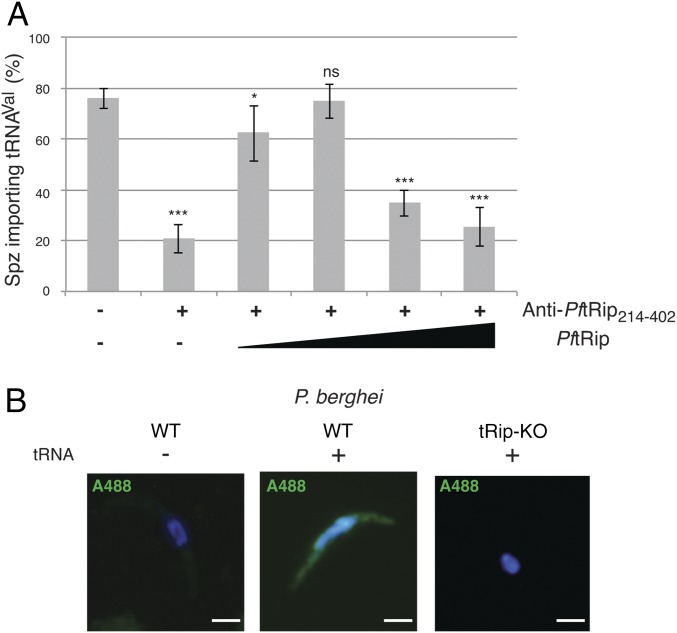

In a first attempt to show that import was dependent on tRip, sporozoites were incubated with an anti-PftRip214–402 antibody to block tRNA binding in a FISH experiment. The number of parasites demonstrating tRNA import was drastically reduced (Fig. 4A). Addition of increasing concentrations of recombinant PftRip restored tRNA import, presumably by competing for the antibody. At higher PftRip concentrations, tRNA import ultimately declined because PftRip also competes for exogenous tRNAs (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

tRip triggers tRNA import. (A) Import of tRNAs in P. berghei WT sporozoites was inhibited in the presence of anti-PftRip214–402 antibody. It was gradually rescued following the addition of low concentrations of recombinant PftRip protein (80 and 160 nM). Higher PftRip concentrations (320 and 760 nM) lead to tRNA sequestration thereby reducing import. Values correspond to the percentage of tRNA-importing sporozoites (n = 50), means are from three independent experiments, error bars are SDs, unpaired t test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns indicates that values are not significantly different (P > 0.1). (B) P. berghei WT and tRip-KO sporozoites were incubated with (+) or without (−) E. coli tRNAVal and were subjected to FISH. Because the tRip-KO parasite expresses mCherry, the probe was 3′ end-labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (A488). (Scale bars, 2 µm.)

P. berghei tRip Is Important for Normal Blood-Stage Growth.

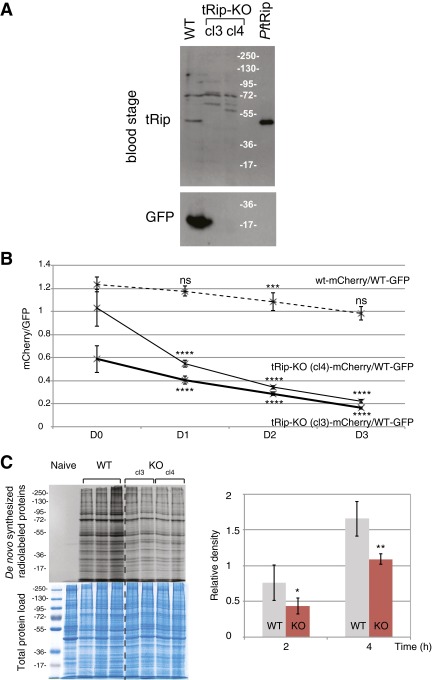

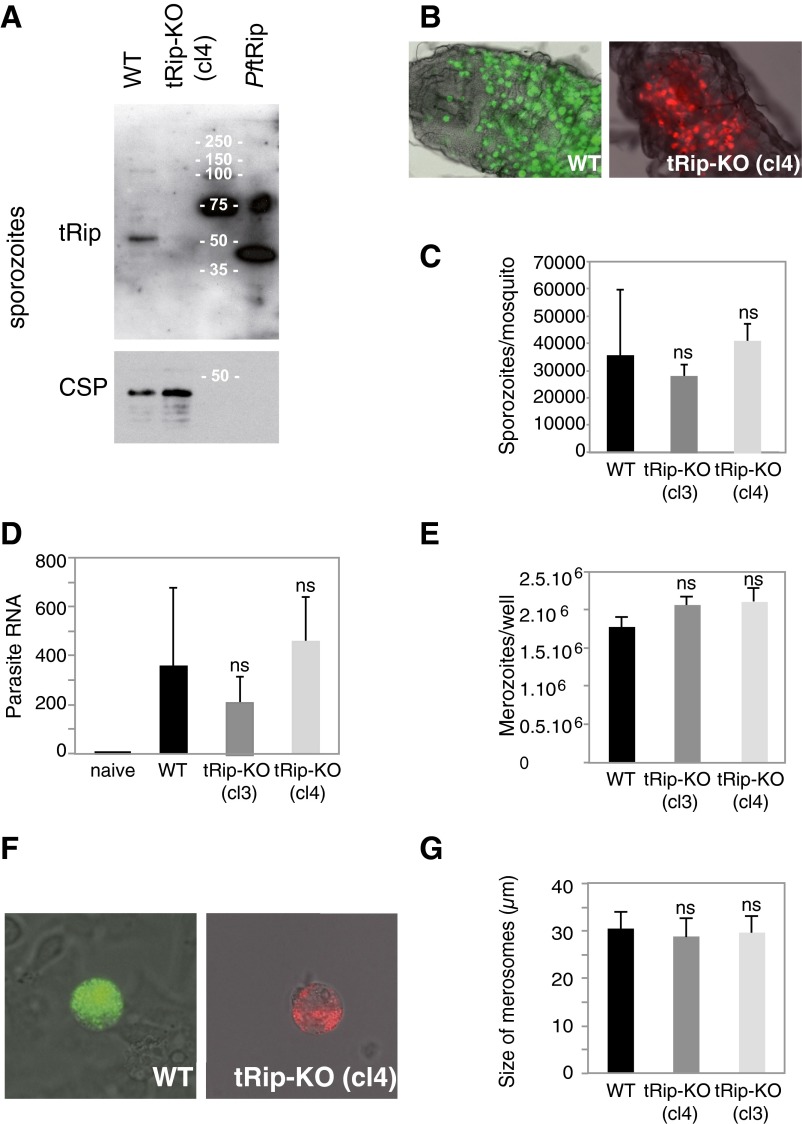

To assess tRip importance to parasite survival, the tRip-encoding gene (TRIP) was knocked out and replaced in the genome of the WT P. berghei ANKA strain by the hDHFR selectable marker and an mCherry cassette via double cross-over homologous recombination (29). Several independent tRip-KO clones were isolated, and successful recombination and the absence of tRip expression were confirmed by Southern and Western blot, respectively (Figs. S6A and S7A).

Fig. S6.

Phenotype of tRip-KO blood-stage parasites. (A) Western blot on blood-stage WT and tRip-KO (cl3 and cl4) parasites probed with anti-PftRip214–402. P. berghei blood stages were matured into schizonts in vitro before analysis. Additional bands around 72 kDa correspond to cross-reactive proteins from the host. (B) Ratio of mCherry+/GFP+ parasites in the blood of 4-wk-old mice coinfected by WT/mCherry+ and WT/GFP+ parasites (dashed line, n = 8) or tRip-KO/mCherry+ (cl3 and cl4) and WT/GFP+ parasites (plain lines, n = 15). Error bars are SDs, unpaired t test: ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns indicates that values are not significantly different (P > 0.1). (C) Protein synthesis by WT or tRip-KO P. berghei blood-stage parasites. Infected red blood cells with WT (n = 3, based on the number of mice), tRip-KO cl3 (n = 2), or tRip-KO cl4 (n = 2) parasites were metabolically labeled with [35S] methionine for 2 or 4 h at 37 °C. The level of de novo synthesized proteins was determined by SDS/PAGE autoradiography. Autoradiograms shown correspond to the 4-h time point. The magnitude of radiolabel incorporation was expressed as [35S] methionine incorporation into proteins relative to total protein load (Coomassie blue staining). Error bars are SDs, and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) between the tRip-KO (red) and WT parasites (gray) translational activities.

Fig. S7.

Prepatent stages of the tRip-KO parasite. (A) Western blot of purified WT and tRip-KO sporozoites. (B) Oocysts of the WT (Left) or tRip-KO (cl4; Right) clones developing in the midgut of A. stephensi mosquitoes 11 d after the mosquito’s infective blood meal. (C) Mosquitoes infected with WT or tRip-KO (cl3 and cl4) parasites harbored similar numbers of sporozoites in their salivary glands 18 d (and onward) after infection. Means are from two independent experiments, with n = 16–30 female mosquitoes. (D) Parasite loads in the liver 46 h after i.v. injection of 104 sporozoites were quantified by RT-PCR analysis. The histogram shows the abundance of parasite RNA obtained from 16 infected mice (for each clone), using the mouse HPRT gene as a standard. (E) Incubation of 2 × 105 HepG2 hepatoma cells with 5 × 104 salivary gland WT or tRip-KO (cl3 and cl4) sporozoites (per well) generated similar numbers of merozoites. (F) Representative WT (Left) and mutant (Right) merosomes, which are merozoite-filled vesicles that bud off from infected HepG2 cells after 60–65 h of liver stage development. (G) Size of merosomes released by WT and tRip-KO liver stages. Error bars are SDs, unpaired t test: ns indicates that values are not significantly different (P > 0.1).

To confirm that tRNA import in sporozoites is indeed tRip dependent, the tRNA import assay was repeated with tRip-KO sporozoites. As expected, tRNA import was not observed in any tRip-KO sporozoite (>100 sporozoites were examined), consistent with complete ablation of tRNA import had occurred on KO of TRIP (Fig. 4B).

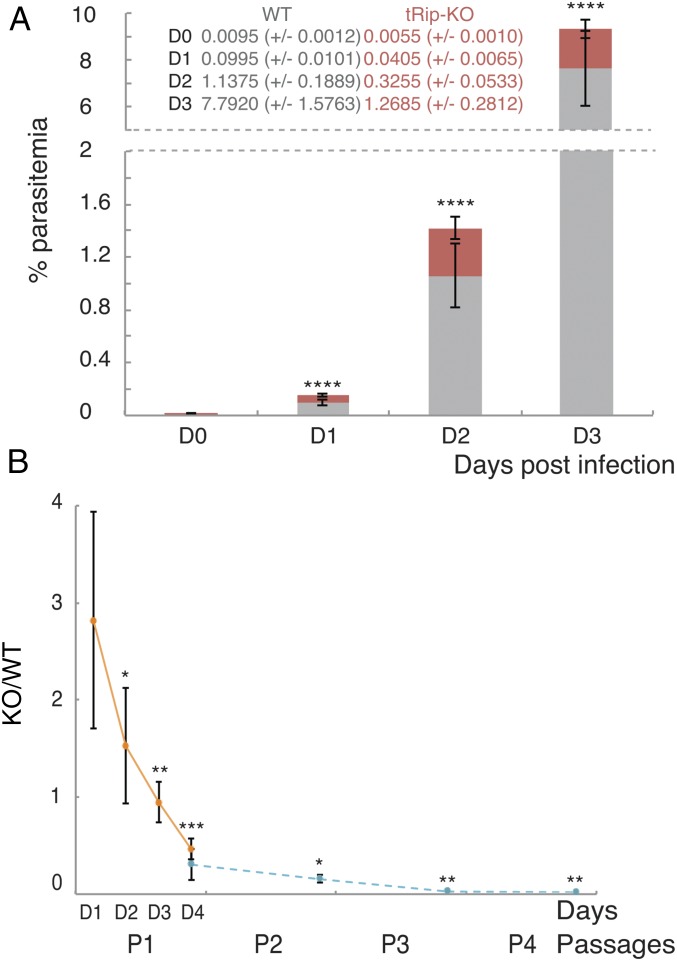

To determine whether tRip played any role in blood-stage replication, mice were coinfected with tRip-KO (mCherry+)- and GFP-encoding WT blood-stage parasites. The proportions of red and green fluorescent parasites were scored consecutively for 4 d during the parasite exponential growth phase (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6B). The proportion of tRip-KO parasites decreased at each multiplication cycle compared with WT parasites. Furthermore, the tRip-KO parasite was completely absent in mouse blood after only four successive passages (Fig. 5B). Thus, tRip appears to confer a selective advantage to the parasite during blood-stage infection.

Fig. 5.

Phenotype of the tRip-KO parasite. (A) Four-week-old mice were coinfected by WT/GFP+ (gray) and tRip-KO/mCherry+ parasites (red). Values correspond to the percentage of red blood cells infected with WT (gray) or tRip-KO (red) parasites, n = 15, error bars are SDs, unpaired t test: ****P < 0.0001. (B) Ratio of tRip-KO mCherry+/WT GFP+ parasites in the blood, measured at days 1, 2, 3, and 4 after infection during the course of a first passage (orange) and at day 4 throughout four repeated passages (blue). Values correspond to the ratio of red blood cells infected with tRip-KO parasites to red blood cells infected with WT parasites, at days 1–4 during the first passage (P1, n = 6) and at day 4 during the three following passages (P2–P4, n = 5), error bars are SDs, unpaired t test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We hypothesized that this phenotype might be a consequence of reduced translational activity in blood-stage tRip-KO parasites. To test this hypothesis, metabolic labeling was performed with [35S] methionine. After 2 and 4 h, equal amounts of [35S]-labeled parasites were analyzed by SDS/PAGE (Fig. S6C). WT and tRip-KO parasites showed the same translational profiles, with more intense labeling for WT, suggesting that translation is globally reduced in the absence of tRip.

To test whether tRip-KO parasites displayed any other phenotype during the parasite life cycle, Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were infected with blood-stage parasites. tRip-KO clones developed normally inside mosquito midguts (Fig. S7B) and yielded normal numbers of sporozoites in mosquito salivary glands (Fig. S7C). Sporozoite infectivity in vivo was then measured by comparing prepatent periods of infection following i.v. injection of 5 × 103 WT or mutant salivary gland sporozoites (per 4-wk-old C57BL/6 mouse, five mice per group). Blood-stage parasites were detected in all mice 3 d after injection, and parasitemia at day 4 was indistinguishable between WT and tRip-KO (cl4) parasites (∼0.06% each), indicating that tRip-KO sporozoites induce a normal pre-erythrocytic phase in the mouse (Fig. S7D). In vitro, tRip-KO parasites developed efficiently inside HepG2 hepatoma cells, releasing similar numbers of merozoites as WT parasites (Fig. S7 E–G). Therefore, the lack of tRip in P. berghei appears to affect the growth of only blood-stage parasites.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate a direct connection between tRip and tRNA import in Plasmodium. This discovery not only reveals unsuspected molecular exchanges between the parasite and its host, but is also the first report, to our knowledge, of intracellular import of exogenous tRNA in any cell.

We find that P. falciparum tRip specifically binds human tRNAs, through its C-terminal domain, with affinity similar to that of well-characterized tRNA-binding proteins such as Trbp111 (7) and ARC1p (11). In agreement with transcriptomic and proteomic data (plasmodb.org/plasmo/), immunolocalization data in P. berghei indicate that tRip is expressed throughout the Plasmodium life cycle, in intra- and extracellular stages (Fig. S4C), and is integral to the plasma membrane of the sporozoite and blood stages (Fig. 2). Crucially, WT P. berghei sporozoites, and presumably other parasite stages as well, can import exogenous tRNAs (Fig. 3), but this capability is lost on disruption of tRip expression (Fig. 4). Together, these data indicate that the malaria parasite has the ability to import exogenous tRNAs via a tRip-dependent pathway. Host tRNAs would help parasite protein synthesis, provided (i) they are substrates for plasmodial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases or (ii) they import bound host aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (we observed formation of such a ternary complex between AspRS, tRNAAsp, and tRip in vitro; Fig. S3C). Imported tRNAs could balance the surprisingly limited expression of endogenous tRNAs or alter a translational bias.

Gene targeting experiments in P. berghei indicate that parasites lacking tRip have a specific defect during the blood phase of the parasite life cycle, i.e., the repeated cycles of parasite multiplication inside erythrocytes is defective. Although lack of tRip is not lethal to blood-stage parasites, coinfection experiments in the mouse blood clearly show that the absence of tRip affects the integrity of blood-stage multiplication (Fig. 5). This phenotype is concomitant with globally reduced protein synthesis in tRip-KO blood-stage parasites, consistent with a scenario wherein host tRNAs are required for robust protein synthesis to proceed (Fig. S6C).

The observation that tRip is important only during parasite multiplication in the blood is unexpected, from both the parasite stage and host cell perspectives. On the parasite side, why would imported tRNAs be important during the life cycle stage in which multiplication is most limited, and which presumably requires less protein synthesis? Blood-stage parasites only multiply 10-fold per replicative cycle, whereas an oocyst in the mosquito midgut or the liver stage in the mammalian host give rise to tens of thousands of parasite progeny during schizogony (Fig. S4A). In this context, it is interesting to note that orthologs of Plasmodium tRip-encoding genes are found only among apicomplexan parasites, which lack an RNA interference pathway (RNAi, except for T. gondii) (30). Imported tRNAs may thus serve as a source of regulatory RNAs. In fact, tRNAs and tRNA fragments act as regulatory molecules in other organisms (31–33). Parasites may thus rely on exogenous tRNAs as a growth regulatory mechanism.

On the host cell side, there is no direct evidence for the presence of tRNAs in mature erythrocytes (34). Red blood cells contain no nucleus, and protein biosynthesis is assumed to be absent in these cells. However, mRNAs for the translational machinery are still detected in mature red blood cells (35). Furthermore, many Plasmodium species preferentially invade reticulocytes (36), which contain high levels of tRNAs (34) compared with mature erythrocytes (35).

The parasite stage(s) that actually imports the host tRNAs for blood-stage growth remain unknown. Among blood stages, the extracellular merozoite is short-lived and does not traverse host cells, whereas the intraerythrocytic stages resides within a parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Therefore, the most likely hypothesis is that intraerythrocytic parasites pump tRNAs across the PV membrane and, secondarily, across the parasite plasma membrane via tRip. It could also be speculated that tRNAs may be imported during the liver stage or even the sporozoite stage, the only stage that can traverse host cells and thus lie in direct contact with the host cell cytosol and tRNAs, for use in subsequent developmental stages. However, cell traversal-deficient parasites have no defect in invading and developing inside hepatocytes in vivo and in vitro, nor in subsequent development inside erythrocytes (28). We cannot exclude the possibility that tRip, may have a function other than tRNA import during blood-stage growth. For example it might interact with aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in a manner similar to other Trbp111 homologs such as yeast ARC1p (8), human AIMP1 (9), and Toxoplasma gondii Tg-43 (10).

In conclusion, our data describing the tRip-directed import of external tRNAs reveal a novel adaptation of Plasmodium parasites to their host, as well as a first occurrence of optimal cell growth dependent on import of exogenous tRNA. Incidentally, tRip function provides a unique molecular system for targeting exogenous molecules into the cytosol of Plasmodium cells.

Materials and Methods

Identification of PftRip Gene.

Additional information can be found in SI Materials and Methods. The PftRip gene (PF14_0401) was identified by blasting the yeast ARC1p (NP_011410) and human AIMP1 (NP_004748) sequences against PlasmoDB (plasmodb.org/plasmo/). The sequence alignment was computed with TCoffee software (tcoffee.vital-it.ch/apps/tcoffee/index.html), and the detection of the transmembrane helix was achieved with the PredictProtein software (https://www.predictprotein.org:443/).

PftRip Cloning and Production.

The PftRip gene was amplified by PCR from a P. falciparum cDNA library (provided by H. Vial, CNRS UMR 5235, University of Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France) and sequenced. Both PftRip and PftRip1–174 were cloned into pQE30 (Qiagen) to produce proteins with a 6-histidine fusion tags at their N termini. The recombinant PftRip214–402, corresponding to the 260-amino-acid C-terminal domain, was cloned into pGEX-2T (Amersham Biosciences) to yield an N-terminal GST fusion protein. Thrombin cleavage occurred at Proline 214 (instead of the cleavage site provided in pGEX-2T); thus, the C-terminal domain of PftRip was consequently referred as PftRip214–402. Tagged proteins were purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions on Ni-NTA resin (PftRip and PftRip1–174, in the presence of 0.005% n-dodecyl β-d-maltopyranoside) or on a gluthatione-Sepharose resin (PftRip141–402) and were further purified by gel filtration (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare) in 50 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. Gel filtration analysis showed that PftRip1–174 and PftRip214–402 eluted at ∼44 kDa, suggesting that they behaved as homodimers, whereas PftRip behaved as a tetramer and eluted at ∼158 kDa (based on comparisons to standards).

Enzymatic Footprinting.

Yeast native tRNAAsp was 5′ or 3′ labeled as described in refs. 37 and 38, respectively. Assays were performed as described in ref. 38 with 50,000 cpm labeled tRNA, 5 µM PftRip in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, and 25 mM KCl, and 0.01 µg/µL 5S rRNA from X. laevis.

Gel Shift Assays.

In binding assays, radiolabeled tRNAs (1,000 cpm/µL) were incubated for 20 min on ice in 25 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 20 ng/µL oligo-dT, with increasing concentrations of PftRip (0–2,000 nM PftRip; 0–1,000 nM PftRip214–402, and 0–8,000 nM PftRip1–174). In competition assays, labeled tRNA (1,000 cpm/µL) and 30 nM PftRip214–402 were incubated with increasing amounts of unlabeled competitor RNAs (0.625, 1.25, and 2.5 ng/µL total RNA, ribosomal RNAs, or crude tRNAs). Assays were analyzed on an acrylamide/bisacrylamide gel (37.5/1) 6% (wt/vol) in Tris/borate/EDTA buffer, at 140 V for 90 min (PftRip214–402) or 150 min (PftRip1–402) at 4 °C. Radiolabeled yeast tRNAAsp was incubated under the same conditions with either 75 nM yeast AspRS alone and increasing concentrations of PftRip214–402 (12.5, 25, and 50 nM) or 30 nM PftRip214–402 and increasing concentrations of yeast AspRS (37.5, 75, and 150 nM).

Immunofluorescence.

Sporozoite membrane extraction was performed as previously described (25). Samples were analyzed with rabbit anti-PftRip214–402 affinity purified using the PftRip141–402 recombinant protein, rabbit anti-GFP antibodies, and mouse anti-CSP serum (39) and detected with anti-rabbit IgG [fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)] and anti-mouse IgG [tetramethylrhodamine-isothyocyanate (TRITC)] (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. Nuclei were spotted with 1 µg/mL DNA stain DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Parasites were observed using epifluorescence microscopy (Axiovert200; Zeiss; 100× objective with the corresponding filters).

Air-dried infected erythrocytes were acetone fixed, permeabilized with ice cold methanol, and incubated with rabbit anti-tRip antibodies (1:50 dilution). Mouse anti–MSP-1 antibody was used as a colocalization marker (PEM-2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The parasite nuclei were stained with DAPI. Parasites were observed using confocal microscopy (LSM780; Zeiss; 60× objective).

Protease Protection Assays.

Infected blood was lysed in PBS containing 0.01% saponin for 5 min on ice. The parasites were washed in PBS and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in PBS, 1 mM CaCl2, and 6 ng/µL trypsin (Promega), without or with 1% Triton X-100. tRip, AMA-1, and GFP were detected by Western blotting with purified rabbit antibodies raised against the recombinant PftRip214–402, anti–AMA-1 rat antibodies (integral membrane protein control), and anti–GFP-rabbit antibodies (cytosolic control).

Solubility Analysis.

Carbonate vs. detergent extraction of membrane proteins was performed on P. berghei blood-stage schizonts as described in ref. 40. Parasites were lysed by three cycles of freeze/thaw in 5 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, containing antiprotease mixture (1/100; Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged 10 min at 16,000 × g. The membrane-containing pellets were then incubated for 30 min on ice in 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.5) or 1% Triton and centrifuged for 15 min at 16,000 × g. All fractions were analyzed by Western blot with specific antibodies against PftRip214–402, AMA-1, and GFP.

Import Assays.

Sporozoites (2 × 104/µL) were first incubated with 0.4 µM radioactive Hepa1-6 tRNAs (50,000 cpm/pmol) in DMEM supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 1 U/µL RNasin (Promega) for 15 min at room temperature and then washed five times with PBS. After cosedimentation (5 min at 9,000 × g), parasite-bound tRNAs were directly dissolved in loading buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM EDTA, 8 M urea, and 0.01% of each bromophenol and xylene cyanol dyes) or subjected to RNase A treatment (0.1 µg/µL) for 3 min at 25 °C in PBS and phenol extracted (TRI-Reagent; Sigma-Aldrich) before analysis on a denaturing (8 M urea) PAGE (19/1) 12% (wt/vol). For FISH experiments, to avoid cross-tRNA hybridization, and because its sequence was sufficiently distinct from the parasite’s tRNAs, E. coli tRNAVal was chosen as a probe. Sporozoites (1 × 103/µL) were processed as described previously and subjected to passive sedimentation for 1 h at room temperature in cell-line diagnostic microscope slides. The slides were then washed with PBS and air-dried overnight. Samples were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, and blocked in 2% (wt/vol) BSA, Denhardt’s 5×, saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer 5×, and 35% (vol/vol) deonized-formamide for 1 h at room temperature. The DNA probes (100 ng/mL; 5′-GAGGTGCTCTCCCAGCTGAGCTAATCACCC-3′) were 3′ end-labeled with Texas Red (TxRd) for probing WT P. berghei sporozoites and with Alexa Fluor 488 (A488) for probing tRip-KO sporozoites. Samples were heated at 75 °C for 5 min and incubated together overnight at room temperature in the dark under constant shaking. The slides were washed for 5 min at room temperature with SSC 2× containing 50% (vol/vol) deonized-formamide, and then SSC 2×, SSC 1× containing 1 µg/mL DAPI, and finally SSC 0.5×. Alternatively, sporozoites (1 × 103/µL) were preincubated for 15 min at room temperature in the presence of anti-PftRip214–402 (1/50 or 1/20) and increasing concentrations of recombinant PftRip (80, 160, 320, and 640 nM) before the addition of 0.4 µM E.coli tRNAVal.

P. berghei sporozoites (2 × 103/µL) were mixed with 0.4 µM Alexa Fluor-labeled in vitro-transcribed E. coli tRNAVal or human 5S ribosomal RNA in PBS and RNasin. Immediately after, the mixture (sporozoites and tRNAs) was put between the slide and coverslip with a drop of 0.5% agar/PBS and observed by epifluorescence microscopy.

Parasite Production, Generation of tRip-KO Mutant Parasites, and Phenotyping Procedures.

Additional information can be found in SI Materials and Methods. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the CNRS animal care and use committee guidelines.

SI Materials and Methods

RNA Preparation.

Native E.coli tRNAVal (tdbR00000456; trnadb.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/) was purchased from Subriden RNA. Total RNA from HeLa or Hepa1-6 cells was extracted using Tri-Reagent LS (Sigma-Aldrich), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Further fractionation on a gel filtration column (Superdex 200; GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl allowed the separation of tRNAs from mRNAs and ribosomal RNAs.

Radioactive 3′ end labeling of tRNAs (Hepa 1–6 crude tRNAs and yeast tRNAAsp) was achieved with [α32P]ATP exchanged in 45 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 50 µM CTP, 10 mM MgCl2, 7.5 mM dithio-erythritol (DTE), and 40 ng/µL E. coli CCase (gift from A. Théobald–Dietrich, CNRS UPR 9002, Institute for Molecular and Cellular Biology, Strasbourg, France) for 30 min at 37 °C. Nonincorporated radioactive nucleotides were removed on a NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare). Before use, all tRNAs and tRNA transcripts were renatured in H2O by heating at 65 °C for 2 min and then cooled for 10 min at room temperature in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2.

The E. coli tRNAVal sequence was cloned under the control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter in pUC119. Transcriptions were performed for 2 h at 37 °C with 50 ng/µL linearized plasmid, 5 µg/mL T7 RNA polymerase in 40 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.1, 10 mM DTE, 2 mM spermidine, 11 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM of ATP, CTP, GTP, 0.4 mM UTP, and 0.1 mM UTP Chromatide Alexa Fluor 546 (Molecular Probes). Nonincorporated nucleotides were removed on a NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare).

Western Blot.

Pellets of purified sporozoites (5 × 105 parasites per lane) or blood-stage parasites (schizonts, 5 × 106 parasites per lane) were dissolved in 60 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 100 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.01% bromo-phenol blue and heated for 5 min at 95 °C. P. berghei tRip was detected by Western blotting with a purified rabbit antibody raised against the recombinant PftRip214–402.

Parasite Production.

Sporozoites.

A. stephensi mosquitoes were raised and infected with GFP-transgenic P. berghei (ANKA 2.34 clone), the tRip-KO mutant parasite, or P. yoelii (17XNL strain) as described in ref. 42, and sporozoites were isolated by dissection of their salivary glands 18–21 d later. Isolated sporozoites glided and were thus considered infectious. As a control, when heated at 50 °C for 30 min, sporozoites were immotile and considered noninfectious (27). When necessary, sporozoites were further purified as described in ref. 43. P. falciparum (NF54 strain) sporozoites were isolated by dissection of salivary glands of A. stephensi mosquitoes infected by P. falciparum (University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands).

P. berghei blood stages.

Thee-week-old Swiss mice were infected i.v. with ∼1 × 106 cryopreserved parasites. Infected blood was collected when parasitemia reached 5–10% and, when necessary, was cultured in vitro for an additional 22 (WT) or 44 h (tRip-KO) to collect schizonts as described in ref. 44.

In vitro differentiation of P. berghei sporozoites into hepatic schizont was achieved in 48 h as described in ref. 45.

In vitro differentiation of P. berghei gametocytes into ookinetes was achieved from the blood of an infected mouse according to ref. 46.

Generation of tRip-KO Mutant Parasites.

For replacement of tRip, a 575-bp 5′ fragment (sense: 5′-GGTACCGTGAGCATCTATATATTTGTTCACGTATCATATTTTAAAAATTG-3′; antisense: 5′-CTCGAGGTTGGGGGAATATAATATCGAATATTATATATATGTGTGTA-AATGC-3′) and a 455-bp 3′ fragment (sense: 5′-AGATCTGTTAGTTGGAAAACGAGGTTATTTAGCTCTGTATAATATCCGAC-3′; antisense: 5′-GAATTCCTTATCGTTGGTGAAATTGGGAAAATCACCTTCTACCATTGTGCATG-3′) were amplified by PCR using P. berghei genomic DNA as template. P. berghei merozoites were transformed and mutant clones were selected as previously described (29). Plasmid integration in the genome was verified by Southern analysis and PCR for eight clones.

Phenotyping Procedures.

Two tRip-KO clones [clone 3 (cl3) and clone 4 (cl4)] were tested for their development in vivo and in vitro and compared with the WT parasite. Swiss mice (3 wk old) were infected i.v. with ∼1 × 106 cryopreserved WT and tRip-KO parasites (clones 3 and 4). Four days later, infected blood was diluted and transferred to recipient mice to a final parasitemia of 0.005% each. Daily, the blood of each donor mouse was monitored for the development of tRip-KO/mCherry+ and WT/GFP+ infected erythrocytes. GFP+ and mCherry+ parasites were counted by FACS (FacsFortessa) from 106 events for each point [n = 15 for tRip-KO (cl3 or cl4] and WT coinfections and n = 8 for the control experiment (WT/mCherry+ and WT/GFP+ coinfections). At day 4 after infection, replicated parasites were diluted and transferred to recipient mice (n = 5) to a final parasitemia of 0.01% (tRip-KO + WT) and were subsequently passaged through four successive rounds of infection.

Monitoring of hepatic stage development in vitro.

HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM growth medium containing 100 µg/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 200 μg/mL neomycin, and 10% (vol/vol) FCS. Cells were seeded into 24-well plates, at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well, and infected with 5 × 104 sporozoites per well. After a 62-h incubation, cells were collected, fluorescent merosomes were counted, their size was measured, and the number of released merozoites was determined by fluorescence microscopy.

Monitoring of hepatic stage development in vivo.

Swiss mice (3 wk old) were infected i.v. with 104 WT or tRip-KO (clones 3 and 4) sporozoites. RT-PCR analysis was performed 46 h after injection using 40 ng total RNA extracted from the liver. Analysis was completed with primers for P. berghei 18S rRNA using the ΔCT method (User bulletin 2; Applied Biosystems).

Detection of protein synthesis activities in blood-stage parasites.

The protocol was adapted from ref. 47. For metabolic labeling, infected red blood cells (3 × 109 infected erythrocytes) were grown in 750 µL RPMI 1640 containing 50 µM methionine, 1 mg/mL glucose, 40 mM N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 1 U/mL heparin, 10% (vol/vol) FBS, and 30 µCi/mL [35S] methionine for 4 h at 37 °C with gentle agitation and in the presence of 5% CO2. Cultures were harvested, washed with RPMI, and incubated in PBS containing 0.1% saponin and anti-protease mixture 1/100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min on ice. Pellets corresponding to labeled parasites were quantified by Bio-Rad protein assay and analyzed on SDS/PAGE.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamara Hendrickson and Ermanno Candolfi for support and discussions and Marie Miller, Oliver Miller, and Joe Chihade for comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge Sylvie Friand, David Bock, Marta Cela, Caroline Paulus, Julien Soichot, and Anne Théobald-Dietrich for assistance. This work was supported by the CNRS, the Université de Strasbourg, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale Alsace, the Ministère de la Culture, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche du Luxembourg (Tania Bour), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grant ANR-07-BLAN-0069-01), and the European Community's Seventh Framework, Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under Grant 223024. This work has been published under the framework of the Laboratory of Excellence: ANR-10-LABX-0036_NETRNA and the equipment of excellence: I2MC.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600476113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gardner MJ, et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419(6906):498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filisetti D, et al. Aminoacylation of Plasmodium falciparum tRNA(Asn) and insights in the synthesis of asparagine repeats. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(51):36361–36371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.522896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopper AK, Pai DA, Engelke DR. Cellular dynamics of tRNAs and their genes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(2):310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salinas T, Duchêne AM, Maréchal-Drouard L. Recent advances in tRNA mitochondrial import. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33(7):320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider A. Mitochondrial tRNA import and its consequences for mitochondrial translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1033–1053. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-092838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Megel C, et al. Surveillance and cleavage of eukaryotic tRNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(1):1873–1893. doi: 10.3390/ijms16011873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morales AJ, Swairjo MA, Schimmel P. Structure-specific tRNA-binding protein from the extreme thermophile Aquifex aeolicus. EMBO J. 1999;18(12):3475–3483. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanasios E, Simos G. Building arks for tRNA: Structure and function of the Arc1p family of non-catalytic tRNA-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(18):3842–3849. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, Han JM, Kim S. Protein-protein interactions and multi-component complexes of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Top Curr Chem. 2014;344:119–144. doi: 10.1007/128_2013_479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rooyen JM, et al. Assembly of the novel five-component apicomplexan multi-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex is driven by the hybrid scaffold protein Tg-p43. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simos G, Sauer A, Fasiolo F, Hurt EC. A conserved domain within Arc1p delivers tRNA to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Mol Cell. 1998;1(2):235–242. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shalak V, et al. The EMAPII cytokine is released from the mammalian multisynthetase complex after cleavage of its p43/proEMAPII component. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):23769–23776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruff M, et al. Class II aminoacyl transfer RNA synthetases: Crystal structure of yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNA(Asp) Science. 1991;252(5013):1682–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2047877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomanbhoy T, et al. Simultaneous binding of two proteins to opposite sides of a single transfer RNA. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8(4):344–348. doi: 10.1038/86228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ménard R, et al. Looking under the skin: The first steps in malarial infection and immunity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(10):701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haldar K, Murphy SC, Milner DA, Taylor TE. Malaria: Mechanisms of erythrocytic infection and pathological correlates of severe disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:217–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvestrini F, et al. Protein export marks the early phase of gametocytogenesis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(7):1437–1448. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900479-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowyer PW, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, Bogyo M. Global profiling of proteolysis during rupture of Plasmodium falciparum from the host erythrocyte. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(5):M110001636. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunnik EM, et al. Polysome profiling reveals translational control of gene expression in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biol. 2013;14(11):R128. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-11-r128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-Barragán MJ, et al. Directional gene expression and antisense transcripts in sexual and asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindner SE, et al. Total and putative surface proteomics of malaria parasite salivary gland sporozoites. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(5):1127–1143. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams CT, Azad AF. Transcriptional analysis of the pre-erythrocytic stages of the rodent malaria parasite, Plasmodium yoelii. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritz HM, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of toxoplasma development reveals many novel functions and structures specific to sporozoites and oocysts. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e29998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauzy MJ, Enomoto S, Lancto CA, Abrahamsen MS, Rutherford MS. The Cryptosporidium parvum transcriptome during in vitro development. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e31715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergman LW, et al. Myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP) localizes to the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium sporozoites. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 1):39–49. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risco-Castillo V, et al. Malaria sporozoites traverse host cells within transient vacuoles. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18(5):593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mota MM, et al. Migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through cells before infection. Science. 2001;291(5501):141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amino R, et al. Host cell traversal is important for progression of the malaria parasite through the dermis to the liver. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(2):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ménard R, Janse C. Gene targeting in malaria parasites. Methods. 1997;13(2):148–157. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum J, et al. Molecular genetics and comparative genomics reveal RNAi is not functional in malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(11):3788–3798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mei Y, et al. tRNA binds to cytochrome c and inhibits caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2010;37(5):668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43(4):613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raina M, Ibba M. tRNAs as regulators of biological processes. Front Genet. 2014;5:171. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith DW, McNamara AL. The transfer RNA content of rabbit reticulocytes: Enumeration of the individual species per cell. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;269(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabanova S, et al. Gene expression analysis of human red blood cells. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(4):156–159. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cromer D, Evans KJ, Schofield L, Davenport MP. Preferential invasion of reticulocytes during late-stage Plasmodium berghei infection accounts for reduced circulating reticulocyte levels. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(13):1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudinger J, et al. Determinant nucleotides of yeast tRNA(Asp) interact directly with aspartyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(13):5882–5886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frugier M, Moulinier L, Giegé R. A domain in the N-terminal extension of class IIb eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is important for tRNA binding. EMBO J. 2000;19(10):2371–2380. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulanger N, Charoenvit Y, Krettli A, Betschart B. Developmental changes in the circumsporozoite proteins of Plasmodium berghei and P. gallinaceum in their mosquito vectors. Parasitol Res. 1995;81(1):58–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00932418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pachlatko E, et al. MAHRP2, an exported protein of Plasmodium falciparum, is an essential component of Maurer’s cleft tethers. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77(5):1136–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bargieri DY, et al. Apical membrane antigen 1 mediates apicomplexan parasite attachment but is dispensable for host cell invasion. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2552. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinden RE, Butcher GA, Beetsma AL. Maintenance of the Plasmodium berghei life cycle. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:25–40. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-271-6:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy M, et al. A rapid and scalable density gradient purification method for Plasmodium sporozoites. Malar J. 2012;11:421–430. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janse CJ, Waters AP. Plasmodium berghei: The application of cultivation and purification techniques to molecular studies of malaria parasites. Parasitol Today. 1995;11(4):138–143. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinnis P, De La Vega P, Coppi A, Krzych U, Mota MM. Quantification of sporozoite invasion, migration, and development by microscopy and flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;923:385–400. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-026-7_27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinden RE, Hartley RH, Winger L. The development of Plasmodium ookinetes in vitro: An ultrastructural study including a description of meiotic division. Parasitology. 1985;91(Pt 2):227–244. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000057334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deans JA, Thomas AW, Cohen S. Stage-specific protein synthesis by asexual blood stage parasites of Plasmodium knowlesi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1983;8(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(83)90032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellot P, Mechulam Y, Le Corre D, Blanquet S, Fayat G. Identification of an amino acid region supporting specific methionyl-tRNA synthetase: tRNA recognition. J Mol Biol. 1989;208(3):429–443. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kleeman TA, Wei D, Simpson KL, First EA. Human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase shares amino acid sequence homology with a putative cytokine. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(22):14420–14425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castro de Moura M, et al. Entamoeba lysyl-tRNA synthetase contains a cytokine-like domain with chemokine activity towards human endothelial cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(11):e1398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Two distinct cytokines released from a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1999;284(5411):147–151. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang XL, Skene RJ, McRee DE, Schimmel P. Crystal structure of a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cytokine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15369–15374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242611799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]